Translation and introduction by Renato Flores. Translated from here.

Introduction

The waste inherent in capitalist production is obvious when we glance around: near-empty planes flying to keep spots on an airport schedule, planned obsolescence almost forcing us to buy a new phone every other year, and year-round fresh fruit shipped to use from all corners of the world.

As capitalist waste leads to more and more obviously ecological devastation, we communists must be louder in proclaiming that another world is possible. Opposed to the anarchy of the market is the idea of a planned economy, and more specifically a socialist one. The centennial objection to planning is that it is impossible to plan something as complex as the economy that results from millions of agents making billions of transactions. However, with computers that are becoming smarter every day and increasingly capable of solving some of the most complex problems in the world, why should economic planning be excluded from these advances?

In jest, this is called “big computer” socialism. This line of thought is seeing a long revival through the rise of dedicated communities on the internet, who are busy envisioning a brighter future. Among these we include the Spanish-speaking Cibcom (short for Cibercomunismo) from whom we have taken the text. “Big computer” socialism represents an optimistic way of thinking: for socialists, it is possible to organize the economy for the benefit of all, rather than just adjust the distribution of wages through a welfare state.

The inherent assumption in “big computer” socialism is that the problems in the Soviet system of planning were not insurmountable, and other alternative planning systems, like the brief Cybersyn experiment in Chile show a way forward. Indeed, there was a glimmer of this possibility in the USSR. Faced with a stagnating economy in the 60s, it was clear to many that the Soviet planning system needed reforms. The road taken was that of the Kosygin-Lieberman 1965 reforms which introduced some market mechanisms, such as using profitability and sales as the two key indicators of enterprise success. These substituted the old Stalinist principle of “business bookkeeping”, where enterprises had to meet planners’ expectations within a system of fixed prices for inputs/outputs, causing perverse incentives such as making badly-made surpluses or increases in product weight as a net positive for the enterprise.

However, there was another option to the introduction of some market mechanisms in the economy: the road of using the available computing technology to help the planners plan and eliminate the perverse incentives. This was the main idea of Victor Glushkov, and his OGAS system. OGAS was not just “the Soviet internet” as it has sometimes been referred to; in its original form, it was supposed to be a system for radically modifying the planning systems of the economy. The original idea of OGAS was never implemented. Instead, it was downgraded and gutted to the point it became a ghost of itself, failing to provide a line of flight for the creation of a new economy. However, the principles behind it still hold, and can guide us in thinking about what shape the future can take. It is in this context that we present a short biography of Victor Gluskhov and the Soviet attempt at having a “big computer” plan its economy.

Glushkov and His Ideas: Cybernetics of the Future

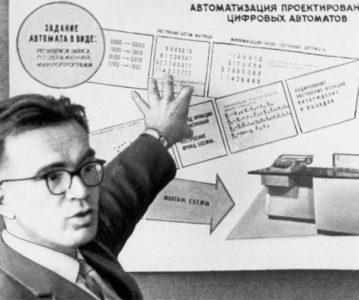

Who are you, Academician Glushkov?

He was one of the most brilliant, talented and outstanding people of the 20th century, a scientist and thinker, whose name has the right to stand alongside such great personalities as Norbert Wiener and Alan Turing, “the tsar of Soviet cybernetics.” Today we talk about Victor Glushkov, the scientist who was one step away from creating a “Soviet intranet” to make the planned economy extremely efficient. He founded and led a powerful cybernetics institute, built a series of original computers, developed and implemented efficient industrial automation systems. And most importantly, he formed the theoretical basis of the socialism of the information age.

Victor Mikhailovich Glushkov was born on August 24, 1923, in Rostov-on-Don, in the family of a mining engineer. In his school days Victor was interested in botany, zoology, then geology and mineralogy, and later in radio engineering and construction of radio-controlled models. Ultimately, physics and mathematics won out. Glushkov’s interest in zoology, which emerged as early as third grade, was expressed by reading Brehm’s book Life of Animals and studying the classification of animals. In fourth grade, fascinated by mineralogy, he read books from the library of his father, who was a mining engineer, and collected minerals. In fifth grade came a passion for radio, and he began making radio receivers from his own schemes. In that same year, together with his father, he built a television set that received broadcasts from Kiev, where the only TV studio in the Soviet Union at that time was located. All of this required a serious knowledge of mathematics, so Glushkov began to study it on their own, mostly in the summer- during vacations. Between fifth and sixth grade, he mastered algebra, geometry, trigonometry for the high school course, and between the sixth and seventh he was already engaged in mathematics on the university program.

In eighth grade, Glushkov became interested in philosophy; he read Lectures on the History of Philosophy and The Philosophy of Nature by Hegel. In addition, he was seriously interested in literature, and in particular poetry. For example, recalled that he once won a bet that he could recite poetry continuously for ten hours. He knew by heart “Faust”, the poem “Vladimir Lenin” by Mayakovsky, poems by Briusov, Nekrasov, Schiller and Heine, the latter in the original language.

In June 1941, Glushkov graduated with a gold medal from the Secondary School No. 1 in Shakhty. He was about to enter the physics department of Moscow University, but on June 22nd, the war came. He immediately applied to the artillery school, but because of very bad eyesight he was not accepted. In the fall of 1941 and spring of 1942 Glushkov worked by digging trenches. In 1942, after the second capture of Rostov by the Germans, he found himself with his mother in the occupied Shakhty. As for many, for Glushkov the war brought a personal tragedy: the Nazis shot his mother – a deputy of the city council.

After the liberation of Shakhty, Glushkov was mobilized to take part in the reconstruction of the coal mines of Donbass: he worked first as a laborer in the mine face, then as a quality and safety inspector.

Already in the fall of 1943, the Novocherkassk Industrial Institute announced the admission of students, and Glushkov was admitted to its heat engineering department. Studying was not easy. He had to earn a living at the same time. Victor Mikhailovich remembers that at first he had to make a living unloading wagons at the rail station, and in the summer he got a job. During the summer, his team of seven people restored the heating of the main buildings of the Institute and repaired the boilers. The following year, Glushkov was engaged in the repair of electrotechnical equipment. Thus, he acquired the professions of plumber and electrician.

After studying for four years, he realized that he was not as interested in thermophysics as in mathematics.

In 1947, he entered the fifth year of the Physics and Mathematics program at Rostov University. For this purpose, in a single year Glushkov took, and passed, all exams of the four academic years that he would have had to do (almost fifty exams!). The following year Viktor graduated from both universities in parallel, obtaining both technical and mathematical higher education degrees.

He began his teaching and research work in the fall of 1949 in the classrooms of the Ural Institute of Forest Engineering. In 1951, he defended his master’s thesis and in December 1955, after graduating from a doctoral program at Moscow University, he defended the doctoral thesis.

In 1956, Glushkov was invited to work in Kiev. He became the head of the computer laboratory of the Mathematics Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR. It was a famous lab. It was located in the two-story building of the former St. Theophanes Monastery Hotel on the outskirts of Kiev. It is here that only five years ago under the command of academician Sergey Lebedev the first electronic computer in the Soviet Union, the Small Electronic Calculating Machine (MESM, after its Russian name), was created.

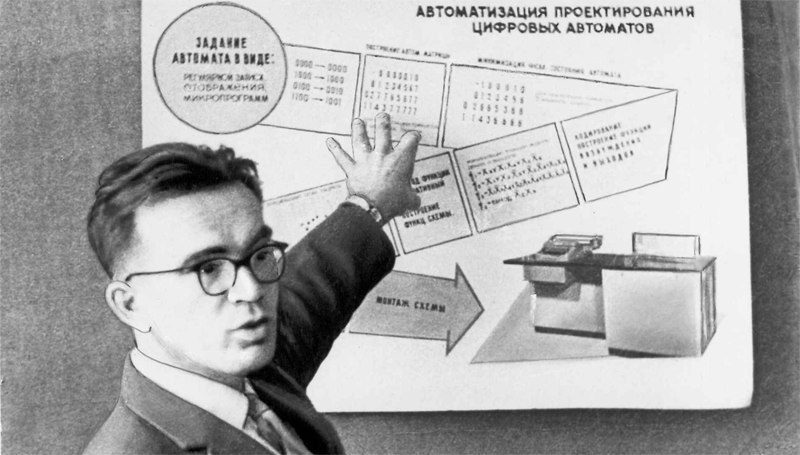

The main feature of computer design at the time was that it was based on “engineering intuition.” The theory of automata, which served as a basis for the design of computers, was poorly developed at that time. In fact, there was only the idea of applying basic operations of formal logic to build automatic devices. Glushkov had to independently familiarize himself with the principles of computer design. Having understood this, he “decided to transform machine design from an art into a science.”

For this, it was necessary to develop a solid mathematical base on which the process of synthesis of electronic circuits could be carried out. Victor Glushkov began to work hard on solving the mathematical problems of computer design, as well as organizing a series of scientific seminars on the theory of automata for the staff of his institute. The seminar was a great success. Glushkov, in general, knew how to infect others with his enthusiasm.

As early as 1958, Glushkov proposed the idea of creating a universal control machine, which, unlike the highly specialized automatic control machines that existed at that time, could be used in any of the most complex technological processes. Three years later, such a machine was built. It was called “Dnieper”. With this machine, for the first time in Europe, it was possible to remotely control a complex process of converting liquid iron into cast steel. It was used to automate one of the most labor-intensive processes in the shipbuilding industry: the cutting of steel plates for the manufacture of a ship’s hull. The hull has a complex spatial configuration and, therefore, cutting the flat steel plates with which the hull will be made is a highly complex engineering task. In the United States, a similar machine was released at the same time, although its development had started earlier. «Dnieper» also broke a record in terms of longevity: it was produced for ten years, while the usual lifespan of a computer model rarely exceeded five or six years.

Glushkov, a passionate promoter of electronic computer technology and cybernetics, immediately saw the incredible capabilities of this science, which far exceeded any fantasy. At the same time, the scientist did not participate in the famous “dispute about cybernetics”, which is now presented as nothing less than “Soviet persecution”.

The essence of Glushkov’s approach was that he did not see in the machine a substitute for the human brain, but rather a special tool that would strengthen it, just as a hammer amplifies the hand and a microscope the eye. Therefore, the machine is not man’s competitor, but an instrument that multiplies his capabilities.

Only in this sense does the machine, or rather the system of machines, become the technical basis for the transition to a new model of economic management. At the same time, Glushkov believed that the effective use of machines in this capacity is possible only in a single complex, when there is no competition, no associated trade secrets, no industrial espionage, etc.

Economic Management

Among Glushkov’s many groundbreaking scientific ideas, we should single out the one that he considered his life’s work. This is his idea of the Automated State System of Economic Management (OGAS). Even at the time, Glushkov himself failed to appreciate the role his OGAS idea could play in our history. Of course, he predicted that the country would face “great difficulties” in managing the economy unless the role of information technologies in planning was adequately evaluated on time, but he could not predict that, at the end of the 20th century, this country would cease to exist.

It so happened that, in connection with OGAS, the Soviet leadership had to choose between two alternatives: to go down the road of improving economic planning on a national scale, or to go down the road to the market as a regulator of production. In his memoirs, Viktor Glushkov said that this question was not so easy to solve. For a long time, the top leadership of the USSR hesitated. The very fact that Glushkov was commissioned to lead a commission to prepare materials for the resolution of the Council of Ministers on the start of work on the OGAS project speaks volumes.

The reasons for the decision to initiate the notorious economic reform in 1965 (t.n. the Kosygin-Lieberman reform), whose main idea was to make the market the main regulator of production, are still not entirely clear. Here is what one of the spokesmen for the 1965 market reform, Alexandr Birman, wrote: “Now, the main indicator by which the performance of the company will be judged and […] on which all its well-being and its direct ability to carry the production schedule is carried out, it is the indicator of the sales volume (i.e. the sales of the products)”. In other words, the economy began to adopt a market logic.

In 1964, it was unlikely that any serious production or science manager could doubt that the future lay in the scientific application of electronic computing technology. For this reason, the idea of OGAS was initially welcomed with enthusiasm. Furthermore, it is not clear how it could happen that, at the last moment, a preference was expressed for the project of the so-called “economists”. The initiators of the economic reform of 1965 were little known, they came out of nowhere, and immediately began to play an almost key role in Soviet economic science. Their activities were directed against Glushkov’s project. In the end, they played a fatal role as the development of the IT infrastructure for the existing planned economic management system was abandoned in favour of market mechanisms.

Here is how Victor Mikhailovich recalls it himself:

Beginning in 1964 (the time when my project appeared), economic scientists Lieberman, Belkin, Birman, and others, many of whom then left for the United States and Israel, began to openly oppose me. Kosygin, being a very practical person, was interested in the possible cost of our project. According to preliminary calculations, its implementation would cost twenty billion rubles. The bulk of the work could be done in three five-year periods, but only on the condition that this program was organized like the atomic and space programs. I did not conceal from Kosygin that it was more complicated than the space and nuclear programs taken together, and organizationally much more difficult, because it involved everything and everyone: industry, commerce, planning bodies, management, etc. Though the project was tentatively estimated to cost twenty billion rubles, the working scheme of its implementation stipulated that the first five billion rubles invested in the first five-year plan would give more than five billion rubles return at the end of the five-year plan, since we provided for self-repayment of the program costs. But over three five-year periods the program would bring at least 100 billion rubles to the budget. And this still could be an underestimation.

But our ignorant economists confused Kosygin by saying that, say, the economic reform would cost nothing at all, i.e. it would cost exactly as much as the paper on which the resolution of the Council of Ministers would be printed, and would result in better results.

This stage of Glushkov’s biography is worth dwelling on. First, because it turned out to be a watershed for the biography of the USSR, and second, because Glushkov’s ideas underlying OGAS have not yet been put into practice anywhere. The Internet turned out to be just another type of mass media and communication system, while Glushkov’s main idea was to create a network that would form the basis for automating economic management.

Unfortunately, and often through the mistaken views of many biographers of Viktor Glushkov, OGAS is perceived as a purely technical thing, a prototype of the internet that was never implemented in the Soviet Union because of the bureaucrats. But this is not true, neither for Glushkov nor for OGAS, at least as this project was originally conceived by the scientist.

In Vitaly Moev’s book-interview “The Reins of Power”, Viktor Glushkov proposed the idea that humanity in its history has passed through two “information barriers”, as he called them using the language of cybernetics. Two thresholds, two management crises. The first arose in the context of the decomposition of the clan economy and was resolved with the emergence, on the one hand, of monetary-commercial relations and, on the other, of a hierarchical management system, in which the superior manager directs the subordinates, and these the executors.

Starting in the 1930s, according to Glushkov, it becomes clear that the second “information barrier” is coming, when neither hierarchy in management nor commodity-money relations help anymore. The cause of such a crisis is the inability, even with the participation of many actors, to cover all the problems of economic management. Viktor Glushkov said that according to his calculations from the 1930s, solving the management problems of the Soviet economy required some 1014 mathematical operations per year. At the time of the interview, in the mid-1970s, already about 1016 operations. If we assume that one person without the help of machinery can perform on average 1 million operations a year, then it turns out that about 10 billion people are needed to maintain a well-run economy. Next, we will present the words of Victor Glushkov himself:

From now on, only ‘machineless’ management efforts are not enough. Humanity managed to overcome the first information barrier or threshold because it invented monetary-commercial relations and the pyramidal management structure. The invention that will allow us to cross the second threshold is computer technology.

A historical turn in the famous spiral of development takes place. When an automated state management system appears, we will easily grasp the entire economy at a single glance. In the new historical stage, with new technology, in the next turn of the dialectical spiral, we are as if “floating” over that point of the dialectical spiral below which, separated from us by millennia, was the period when the subsistence economy of man was easy to see with the naked eye.

This is what the scientist was aiming at! It should be noted that the U.S. intelligence agencies fully appreciated the seriousness of his ideas. In Glushkov’s “testament” you will also find such thoughts:

The Americans were the first to get agitated. Of course, they are not hedging bets on a war against us, it is only a cover, they are trying to crush our already weak economy with an arms race. And, of course, any strengthening of our economy is to them the worst of all things. So they immediately opened fire on me with every conceivable caliber. Two articles appeared first, one in Victor Zorza’s Washington Post and the other in the English Guardian. The first one was called “The punch card runs the Kremlin” and was aimed at our leaders. It read as follows: “Academician V.M. Glushkov, the czar of Soviet cybernetics, proposes replacing the Kremlin leaders with computing machines.” And so on, a lowbrow article.

The article in the Guardian was aimed at the Soviet intelligentsia. It said that Academician Glushkov proposes to create a network of computer centers with databanks, that it sounds very modern and more advanced than it is now in the West, but that it is not done for the economy, but it is in fact it is an order of the KGB, aimed at storing the thoughts of Soviet citizens in data centers and monitoring every person.

Glushkov was fully convinced that the CIA had a hand in the campaign against OGAS. But the fact remains that the draft decree of the Council of Ministers on the start of the OGAS deployment, which had already been prepared, was pushed aside.

What happened after OGAS?

No, OGAS was not completely buried. Glushkov was simply offered a compromise solution: downgrade the project. In other words, to develop automated control systems in such a way that they do not cover the entire economy as a whole, but first only individual ministries, industries or enterprises with the prospect of later unifying them into a single unit. Glushkov’s ideas were interesting to the military. He was invited to provide scientific guidance for the introduction of automated control systems in several defense ministries, each of which established special research institutes for this purpose. From that time until the end of his life Glushkov lived between two places- half of the week in Moscow, and the other half and weekends in Kiev.

The fact that the OGAS idea was not accepted in its entirety upset Viktor Glushkov very much, but he was not going to give up. Furthermore, the second half of the 1960s was characterized by the peak of his theoretical and organizational productivity. He worked on the creation of various individual machines. Interorgtekhnika-66, MIR-1, Promin, Promin-M, Dnieper MN-10M and a number of others of his computers received awards.

1967 was an eventful year. The «Lviv» complex, the first automated management system in the USSR, was put into operation. It was installed at the Lviv television plant. In developing this system, many principles were developed that served as the basis for other types of automated management systems. The introduction of the “Lviv” system resulted in a 7% increase in production, a 20% decrease in inventories, a 10% increase in current asset turnover and a significant reduction in engineering and administrative staff.

Glushkov considered as a serious strategic error the decision of the country’s leaders not to force work towards the development of their own original systems, but to copy the architecture of the IBM System/360. He believed that this path, sooner or later, would lead [the USSR] to a dead end. That happened later, but in the 1970s it was still not clear to many. On the contrary, there was a rapid growth in the production of computers. The ES EVM series, which were third generation medium and high performance universal machines, compatible both with each other and with IBM S/360, was developed.

In 1973, a unique publication, “The Encyclopedia of Cybernetics” was completed in two volumes, which was published the following year with a circulation of thirty thousand copies. It was designed not only for specialists in the field of cybernetics, but for all scientists, engineers, managers, and students interested in information processing. It is a truly fundamental work, in which hundreds of scientists from many cities of the USSR collaborated. But the main work was carried out by the Institute of Cybernetics of the Ukrainian SSR under the command of Glushkov.

Glushkov’s monograph “Macroeconomic Models and Principles of OGAS Construction” was published in 1975. This book describes the experience of using computer technology in the management of economic processes, accumulated over a decade and a half, shows the methods for forecasting and managing discrete processes, presents operational planning and management models, examines the problems of human resource and salary management, and offers a new structure of the OGAS, which corresponds to the then level of technology development informatics, and to the stages of its creation.

The concept of the OGAS was directly related to the academic’s social and political views. Take, for example, his idea of a non-monetary distribution, about which both party and state leaders and official economists tried to keep silent. It is indicative that when preparing the first draft of the OGAS, the part related to this topic was immediately excluded from consideration as premature, and all preparatory materials were ordered to be destroyed.

However, Viktor Glushkov continued to work on this problem. To begin with, he suggested properly organizing money distribution, proposing to divide the monetary circulation in the sphere of distribution into two sectors, in one of which only “clean” money would circulate, while the rest of the money would remain in the other, so that the “slippery sector” can then be eliminated little by little. To this end, he suggested establishing special banks.

To some, such proposals may seem too bold and even fantastic, at least the kind of proposals that, if undertaken, can only be implemented gradually and not immediately. This is roughly what happened with the OGAS in the mid-60s. It was not rejected in principle, but they decided to implement it gradually, not immediately.

It is difficult to find important scientific problems of the time, which Glushkov would not have tried to consider and find an original solution to them. His articles were published in the journals “Voprosy filosofii” (Problems of Philosophy) and “Filosofska dumka” (Philosophical Thought). He dealt with medical problems. Glushkov made a lot of efforts to put cybernetics at the service of pedagogy, and he achieved a lot in this field. Classrooms with automated teaching and knowledge control systems were supplied to even rural schools in Ukraine in the 1970s. As for the training of personnel for cybernetics and computer technology itself, the schools of programmers and engineers, the foundations of which were founded by Glushkov in the late 1960s on the basis of the Kiev Polytechnic Institute and the Taras Shevchenko University, are still considered one of the most prestigious scientific schools in the world. He not only formulated the general principles of various projects, but also organized the work of the team and always tried to bring each idea to its “embodiment in metal”.

But many things have not yet been done. And it is rather the future than the past of computer technology, economic science, and cybernetics, which aims to become, among other things, a science of managing socio-economic processes by the means of machines.