Ira Pollock examines the difficulties of left electoral strategy regarding the question of imperialism and affirms the importance of upholding strong anti-imperialist principles in electoral campaigns. Otherwise, the left itself can become an arm of the imperialist state.

The Left on Elections

The issue of electoral politics has long divided the Left. In contemporary discourse, the most visible dispute concerns the proper strategy for conducting campaigns. Within the Democratic Party, centrists and left-leaners disagree over the best way to win elections: should the party press leftward and focus on working-class struggles, or appeal to a moderate base, win over fence-sitting independents, and snag Republican defectors? For them, it’s largely a matter of strategy.

As you move to its left fringes and beyond the Democratic Party, the conflict morphs into a question of what core principles leftists should compromise to take state power. For instance, one debate within the ranks of DSA hinges on whether the organization should require endorsees to take a hard stance against the occupation of Palestine. In other words, it’s a question of strategy versus principles.

But all of this is only the tip of the iceberg. To even accept the terms of these debates, one must hold a matrix of positions that are by no means orthodoxy on the Left. Many socialists balk at the prospect of spending limited capacity on elections in the first place. For these leftists, to participate in electoral politics is to already lose the struggle for working-class power, to engage with it on the wrong terrain.

Sophia Burns, an incisive theorist and practitioner of revolutionary politics, offers a compelling articulation of why “building institutions outside of the state and against it offers a more effective road to social power than protests and elections.” The issue cuts deeper than just the most effective way to build power. It concerns whether it’s even possible for the working class to take power through elections. Burns’s is one of the more thoughtful accounts of why it isn’t, but some leftists are less sophisticated in their analysis.

Consider the circulation on social media of the following Rosa Luxemburg quote, taken radically out of context to justify electoral abstentionism:

“The entry of a socialist into a bourgeois government is not, as it is thought, a partial conquest of the bourgeois state by the socialists, but a partial conquest of the socialist party by the bourgeois state.”

Once you get this far left, the electoral debate is no longer one of strategy or principle, but one of power and agency. The crux of the question boils down to this: can proletarian agency be developed through electoral campaigns? That is, can the working class, broadly defined, build power through elections?

Questions of Agency

The first part of the electoral question asks whether an elected official can actually make their own decisions while embedded within the state apparatus. Once elected, do the parameters of the game so determine and channel the actions of participants that their discretion vanishes? Do elected officials actually wield state power or are they simply interchangeable cogs in the state machinery? An optimistic answer to this question is a premise of electoral work, an assumption baked into the whole project.

The second question is whether an elected official can exercise specifically proletarian agency through the state. Can they exercise that agency as a proxy for the working class and oppressed? Or has their social position changed such that any action they take serves some facet of capital or empire? For electoral campaigns to build proletarian agency, they must be able to partially capture the state by embedding a proletarian agent (the elected official) within it and build proletarian power enough outside the state to hold the elected official accountable to the interests of the working class. The only alternative is to bank on the ongoing moral fortitude of the candidate. So, can the agency of elected officials be proletarian in nature? Socialist electoral politics presupposes an affirmative answer to this question.

Though it is by no means a given, let’s grant that elected officials maintain their agency and that they can act as agents of the proletariat. What new dynamic do they acquire by wielding state power? One thing is certain: by capturing a piece of the state, the power of a leftist acquires a new, imperialist dimension.

Alternative Practice

Returning to Burns’s point concerning alternatives to electoral politics, her preferred strategy is called base building. This approach to building power is gaining steam on the Left. DSA Refoundation Caucus explains base building as follows:

Base building means constructing stable institutions that can bind our base together [by] building roots in the day-to-day fights of the broadest layer of the working class and oppressed…This means far more than just being able to move people to the polls. It means being able to move entire workplaces, neighborhoods, and campuses into fights on a day-to-day basis.

Refoundation does not explicitly oppose electoral politics but does favor an approach that builds working-class power independent of elected officials and outside state channels.

Sophia Burns identifies base building as one of four tendencies on the Left. These tendencies are 1) government socialists, 2) protest militants, 3) expressive hobbyists, and 4) base builders. These tendencies generally coexist and overlap within the same organization, but the schema is useful; it roughly coincides with different analyses of power and how to build proletarian agency. Electoral politics is the bread-and-butter of government socialists. It is, almost by definition, what they do.

Anti-imperialism exists within all of these tendencies. A promising example of such work within the base-building paradigm is the Tech Workers Coalition and its efforts to purge tech companies of Pentagon and ICE contracts. Another compelling example, one that incorporates aspects of both protest militancy and base building, was the 2008 dockworkers strikes, a show of structural power to demand an end to the U.S. occupation of Iraq.

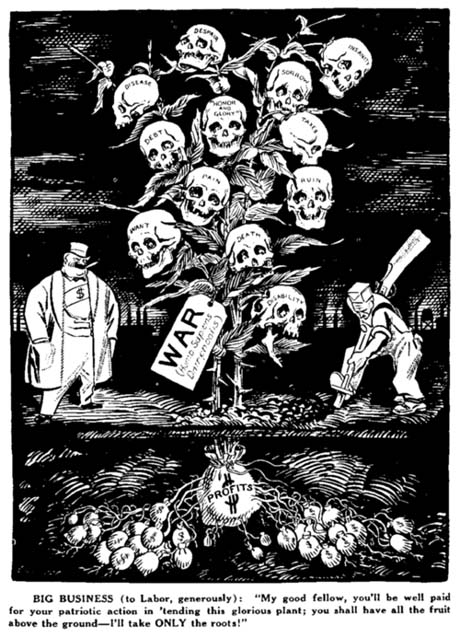

Among these four tendencies, government socialism is unique in regards to the question of imperialism. Unlike the other three, successful government socialism, at least at the national level, endows its practitioners with an imperialist dimension to their agency. It gives them a seat at the table of global empire. Without great care, electoral work can turn leftists into actual, practicing imperialists.

Agency of Empire

Imperialism isn’t, strictly speaking, a capitalist endeavor. Capitalism often drives empire, but imperialist domination is not unique to capitalism; it is unique to statehood. The logic of capital accumulation and the logic of imperial expansion are often intertwined, though not identical. States of all types, capitalist and non-capitalist alike, have engaged in modern projects of imperialism. Accordingly, being anti-capitalist doesn’t necessarily entail being anti-imperialist. However, being a socialist does.

Socialism is intrinsically anti-imperialist because it is intrinsically internationalist. Marx declared “Workers of the world unite,” not just workers in the core of empire. The proletariat can’t be free as long as it is under the yoke of the bourgeoisie or of an imperial oppressor. Accordingly, when playing the game of state entryism, being anti-capitalist isn’t enough. We must oppose empire if we are to sit at its helm.

By entering into the state apparatus, a candidate necessarily takes on a role in the operations of Empire. A federal politician must regularly decide how the world’s primary imperialist state acts on the global stage. From controlling military spending to authorizing new presidential war-making powers, it’s part of the job to make decisions with an intrinsic imperial dynamic. Nowhere else does a successful campaign endow leftists with the power to serve as architects of empire. Dockworkers can block shipments of munitions. Tech workers can pressure their employers to drop Pentagon contracts. In these spaces, leftists can be anti-imperialists, but they can’t accidentally take the reigns of empire and wage imperialist wars. When candidates in national campaigns succeed, they do gain this power. Where a weak commitment to internationalist principles might make poor socialists of other leftists, it makes active imperialists of elected officials.

Rules for Electoral Practice in the Core of Empire

To qualify for an endorsement from a leftist organization such as DSA, a candidate in a U.S. election should commit to internationalist principles. Particularly at the federal level, where a successful candidates agency can acquire an imperial dimension, this should be the top priority. Leftists can organize for other priorities at other levels of government and through alternative avenues without directly confronting the question of empire. At the federal level, the question is front and center.

At a bare minimum, when vetting potential national candidates, organizers should ask for an express commitment to anti-imperialism and to opposing U.S. wars. Any federal-level candidate that declines to make such a commitment should be disqualified from endorsement considerations.

A second level of vetting should concern specific issues. Does the candidate support eliminating military aid to Israel until it ends the occupation of Palestine? Does the candidate support legislation to end U.S. involvement in the Saudi war on Yemen? Does the candidate support a drastic reduction in military spending? Does the candidate support revoking the president’s authorization to wage the War on Terror indefinitely? For national-level candidates, the answers to these questions should be weighted at least as heavily as to those concerning domestic issues such as Medicare for All and housing.

Finally, and this is good practice for sub-national candidates and on domestic issues as well, consult the candidate’s record (if they have one). For federal candidates, closely scrutinize their record on foreign policy. Did they vote to authorize the invasion of Iraq? Have they voted to fund the occupation on an ongoing basis? Have they voted to increase the military budget? Did they vote in favor of a resolution to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital? This record, if it exists, should be weighted more heavily than the candidates professed values. A federal candidate that has consistently supported military adventures, an expanded Pentagon budget, colonial repression overseas, or any number of other imperialist projects, should not receive leftist support regardless of their stated principles or credentials on domestic issues.

These guidelines should be a bare minimum for socialists practicing electoral politics in the heart of Empire. We cannot sacrifice the lives and dignity of those outside our borders for the sake of domestic priorities. Electoral socialists are playing with fire; they run the unique risk of becoming imperialists by virtue of their success. They must take this danger seriously. Medicare for All in the U.S. is not a victory if we must wage genocide in the Middle East to get it. Let’s not burn the world down to warm our home.