Alexander Gallus concludes his saga on the Bavarian Soviet Republic and tries to draw political lessons from its failures.

The leader of the Bavarian November Revolution lay on the street in his own blood. As the shocked adjutants gathered around the lifeless body of Kurt Eisner, three soldiers with rifles and hand grenades ran towards them, shouting, “And now we shall pay a visit to Parliament! Time to clean up.” Appalled at this call to revenge, one of Eisner’s associates—Benno Merkle—grabbed one of the soldiers. He pointed at the corpse, crying “Look at the one you want to avenge! If he could say any last words he would say: don’t avenge me!” 1

Renouncing violence and striving for a peaceful revolution, the pacifist followers of Eisner were outdone by the reality they had gotten themselves into. Getting a hold of the nationalist assassin Count Arco von Valley, a crowd pummeled him, shooting his throat and lodging a bullet in his skull. After being brought to the hospital unconscious, at the order of Merkle, von Arco did not stabilize to stand trial for another few months, until August of 1919. With the assassination of Eisner, revolutionary calls overflowed the streets of Munich. During a meeting of Parliament that same day, Erhard Auer—the SPD rival of Eisner—was wounded and two other members of parliament shot from the revolver of a council leader. With the remaining parliamentarians escaping from the city to northern Bavaria, it was clear that the floodgates which were opened would not be closed again any time soon.

As the local poet Oskar Maria Graf described the events following Eisner’s assassination:

The bells started ringing from all church towers, the trams stopped at once, here and there a red flag was being hung out a window with a black ribbon, and a heavy, uncertain silence came down. All people walked downtown, with grimaced faces. . . suddenly a fully laden truck with red flags and machine guns drove by, and from it loudly came calls: ‘Revenge! Revenge for Eisner!’. . . The masses started streaming through the city. This was different than the 7th of November. . . The thousand little storms became one, and a single, dull, dark and uncertain eruption started.” 2

By all estimates, more than 100,000 of the 600,000 inhabitants of Munich marched at the funeral procession for Eisner. All those vaguely sympathetic to revolution showed up, even those who, in due time, through the extended failure of the revolution, were to be drawn into the fascist reaction around the Thule society and bribed by the German military. Many later SA members and leaders showed their support for the revolution and attended Kurt Eisner’s funeral march alongside Russian prisoners of War. As his authoritative biographer Volker Ullrich shows, Adolf Hitler was a part of the leading procession carrying Eisner’s coffin. 3 Workers and soldiers discussed emotionally how to carry forth the revolution. As it were, however, confusion, phrase-mongering, and anarchistic idealism were on the order of the day in the councils and no effective government came about from the escalation.

Late February negotiations between SPD and USPD in the northern German city of Nürnberg, came to a conclusion, after a week of intense discussion, to form a temporary coalition that was to last a mere three weeks. Feeling safe to recommence a meeting of Parliament for the first time since the tumultuous day (February 21st) of the assassination, the congregation on March 18th voted SPD’s Johannes Hoffmann as Bavaria’s Prime Minister. Within the ruling system of “dual power”, however, this government had little substantial claim to do things as it saw fit, and set its headquarters in the northern Bavarian city of Bamberg.

The eyewitness Ernst Müller-Meiningen says of those tumultuous days, “only those who were in the middle of things back then knew that the government was without real power, that the councils had all the guns, and hence the power”. 4 As mentioned in the first article, councils, despite their harboring of radical sentiment, were tolerated as a safety valve by the bourgeois, through social-democratic politicians and their military friends manipulating and fighting for their politics within them. Indeed, many social-democrats and independent social-democrats were later successful in adding workplace councils to the constitution of Germany, lasting until today.

Many prominent members of the Independent Socialists were strongly in favor of and involved in the struggle for councils, such as Däumig and Koenen nationally or Sauber, Maenner, Hagemeister in Bavaria. This was not meaningfully discouraged by those in the party who in fact feared revolution. It could actually be argued that a naive belief in councils within the party was cleverly utilized by such figures as Haase and Kautsky, who presumably never desired them at all. The belief in councils as bringing about socialism was naive precisely because the mere propagation of and even organizational work for councils (for whose creation there was much effort expended by the Bavarian revolutionaries and Communists) did little to solve the problem of the political leadership of workers. Often, throughout the Bavarian councils, their creation did nothing to further the actual political program needed to get to a system run by workers but saw opportunist demagogues like Hitler (who was as of yet still a politically unknown and awkward figure) get elected as council leaders.

In his article “Driving the Revolution Forward”, Kautsky harshly denounced the Spartacists because of their ‘street actions’ and their calls for ‘total control to the councils’; yet, not a harsh word is dealt to those leftists of his own party, who, according to historians like Morgan and Beyer, were equally or perhaps even more dedicated to the council idea and involved in its implementation than many Communists. With mass strikes in early 1919 shutting down large swaths of the country’s train system, it was the USPD’s most radical party branches which suffered and failed to send delegates to the Berlin Party Conference of March 2 to 6. Comprising roughly 20% of the party’s membership, the USPD’s largest party branch in the town of Halle (a local stronghold of the latter communist party), sent a mere 2 out of 176 delegates. Bavaria, another radical stronghold with almost 10% of the party’s members nationally, sent a meager 4 delegates. 5 The believability to which this was just mere coincidence, without foul play or party machinations, must be left to the reader’s imagination.

At the Party Congress, it was the party left’s most well-known figure, Däumig, who was elected as party chair, next to Hugo Haase. As a reminder, it was Haase who had (although, begrudgingly) stood before the Reichstag to read the Social-Democratic Party’s statement in favor of the Kaiser’s war credits… Causing an unprecedented scandal at the Berlin Congress, Haase refused to serve as party co-chair with Däumig. Morgan states, “Däumig, never one to push himself forward, then withdrew his candidacy” 6. Largely dominated by empty compromises, the party’s meetings between the 2nd and 6th of March provided no clear plan to approach the German proletariat with, nor one for the future of the party.

The fact that perhaps as many as 50% of its members were not proportionally represented at the congress, was unfortunately not exploited by Däumig and the left, who would have had great cause to stall and explode operations to win members’ sympathy for a fight against the right and ‘moderates’, and for their programmatic aspirations towards a dictatorship of the proletariat. Alas, Däumig, who had wisely called the rebelling Spartacus League a ‘suicide club’, proved himself no grander socialist and revolutionary, failing to transcend the blinding bureaucratic morass of German social-democratic tradition inherent in the USPD. Incapable of translating the urgent needs of workers into clear party program and direction, this party which was to win over a third of the SPD’s branches, failed the people at a crucial moment, when the lives of countless socialists and workers hung in the balance in the face of a militarist repression which sought to violently destroy the popular desire for socialism.

Back in revolutionary Bavaria, Eisner’s USPD successor and delegate Ernst Toller (who had foiled an early assassination attempt on the Prime Minister), scrounged a fighter plane and WWI ace fighter pilot in a last-ditch attempt to reach the Berlin conference. Recounting what was then a novel human experience, Toller wrote:

“Under southern blue skies we start. I sit behind the pilot in a small space. Through a small square hole on the floor bombs had been thrown on human beings and houses during the war, now it serves as my window to the disappearing earth. It’s my first flight. The black forest, the green fields, the tan mountains and valleys become flat, colorful, fenced in squares from a kids toybox, bought in a store, put together from kids hands. Suddenly clouds tower over us, the earth is covered in fog, strangely pulling me to it. The desire to fall, to sink comfortably, confuses my senses. […] Suddenly the airplane swoops down, sinking, and before I can put on my safety belt the machine whizzes down vertically towards the earth and drills its nose into the field.” 7

Surviving the crash landing in rural Bavaria with mere bruises and bloody noses, Toller and his pilot stumbled through the field to take shelter at a restaurant, ominously filled with conservative peasants, before hijacking a train and returning to Munich. Returning for the all-council congress, Toller reacted harshly to his party colleague Felix Fechenbach’s speech, which warned of an impending civil war and urged them to further negotiate with the bourgeois government of Parliament. Two days later Ernst Toller was elected head of the USPD in Bavaria. Splitting the party from the national USPD, he promised in a lofty speech to abandon its prior cooperation with the SPD, to not participate in Parliament, intending instead to work towards establishing a dictatorship of the Proletariat and cooperating with the Communist Party, (KPD), which began to have a local presence with the opening of their Münchner Rote Fahne on February 28th. It, in turn, had no intention of cooperating with the soft-hearted successors of Eisner.

At the beginning of March, the Berlin Central Committee of the KPD sent, among others, the Russian born revolutionary Eugen Leviné to Bavaria (not to be confused with the ‘idol’ of Bavarian communists, Max Levien). Upon his arrival in Munich, Levine commented in a letter to his wife that “my friends here are most childish.” Against their “naive” support for the anarchists and idealistic council leaders, he strove to tactfully educate the local KPD members. Valuing the importance of making clear to workers certain necessary goals of struggle through speeches and articles, introducing cadre building to the KPD local – and setting a strong contrast to the vague prophetic moralism of Eisner and his successor – he, not unlike many of his party comrades, neglected the importance of other matters of politics. Before being sent to take over the Münchner Rote Fahne, Leviné had tremendous success agitating for the KPD in the Rhineland at the onset of the November revolution, but was of the minority KPD delegates at its founding congress which voted to boycott working for the advancement of communist views within both parliament and the reformist trade unions

Beside the eternal debates within Munich’s councils, the SPD government of Hoffman was busily consolidating its power in northern Bavaria with the Army, reneging on its pledge to keep various USPD members on its cabinet. The independent organization of right-wing death squads, such as the Knight von Epp’s Freikorps division, meanwhile accelerated. Incidentally, one of von Epp’s local Munich recruits was the rapist Josef Meisinger, later executed Second World War criminal and “Butcher of Warsaw” as he was to be known in his employ as Commander for the Nazis. The declaration of a Soviet Republic in Hungary on March 21st of 1919, with the communist Bela Kun at its head, only accelerated the revolutionary ambitions of the mass of workers and soldiers, and also the activity of this reaction.

With the victory of the communist-led council revolution of Hungary, revolutionary dreams became very widespread in Bavaria. Just six days before Hungary’s new declaration, the Soviet government of Ukraine sat in Kiev after the Bolshevik’s successful military offensive against the German puppet regime there. That meant that only Austria – where the tremendous level of working-class organizing in Red Vienna saw solidarity calls for a Soviet government, and massive socialist demonstrations grew larger daily – stood in the way of the Bavarian Soviets having a land connection to Soviet Russia. Lenin promised to send three million Russian soldiers to secure the European revolution.

While the Munich KPD was busily responding with an excited and optimistic communique to the Hungarian revolutionaries, Eugen Leviné was not unaware of the leviathan and consuming struggle in Russia as well as the danger of the Bavarian situation:

“It seems to me that in Munich far too much importance is placed on high politics and that an excessive preoccupation with the problems of a great future results in neglecting the essential tasks of the moment, vital for establishing that future. True, we defend the principles of the Soviet system but we have yet to create the prerequisites to guarantee the establishment of that system. These prerequisites do not exist, and, while at the Bavarian Soviet Congress, Comrade [Max] Levien advocated and defended on principle the Soviet system, he will surely share my opinion that the proclamation of a Bavarian Soviet Republic under the prevailing conditions of the country, would be disastrous and would have disastrous consequences.” 8

These “prerequisites” to him were not just the consolidation of the Communist Party to win a stated majority in Soviets, but for communists to actually enhance their activity in, and themselves further the building of councils. His belief was that Communists ought to “speed up the building of revolutionary workers’ organizations[!]. . . We must create workers’ councils out of the factory committees and the vast army of the unemployed.” The indecisiveness of such vague terminology by Levine was unfortunately not restricted to mere rhetoric. It was more so the highest expression of communist politics in revolutionary Bavaria.

The reality and actual situation of “high politics” in Germany and Bavaria were, however, that overall a third of all parliamentary votes went to the SPD and another two-thirds to liberal and conservative parties, with marginal (yet not insignificant) votes for the USPD. The Munich KPD and Levine’s approach – of on the one hand attempting to criticize left illusions, while on the other encouraging it in its active delusions, ordering workers and party members in Munich to organize councils – was contradictory and, indeed, dangerous and reckless; This is simply because of the immense size and domineering strength of that camp in Germany which infamously advertised themselves making “Sausages out of Spartacists”.

Calls by the 1st Bavarian infantry regiment and worker demonstrations for a pronouncement of a Soviet Republic of Bavaria rose to a fever pitch in the first week of April. SPD delegates from nearby Augsburg, compelled by the general mood and at their members’ forceful insistence, were sent to Munich with the demand to proclaim a Soviet republic. Emerging coalition talks in Munich by representatives of the USPD, SPD, Farmers’ Union, and anarchists were all joyously unified in their desire to fulfill the goal of creating a Soviet Republic after the model of Hungary. Dreading the growing influence of the KPD, military leader Schneppenhorst, the ‘Noske of Nürnberg’, and the SPD, participated in this ‘council republic’ from above in order to manipulate proceedings, stall and buy time for their military consolidations.

Asserting that this premature “seizure of power” by the Soviets would play directly into the hands of their more nefarious enemies and drown the councils in blood, Levine unpopularly interrupted the second coalition meeting with a speech denouncing the proclamation of this ‘pretend Soviet Republic’, refusing any cooperation in the government. Spending the last of Rosa Levine’s savings on taxi fares, the KPD sent speakers throughout the city for two days, trying to warn the people of the inevitable and dangerous failure of this proposed republic. Regardless, two days later, on April 7th, the people of Munich woke up to the news that they were, as of midnight, now living in a “Dictatorship of the Proletariat”. On the same day, most large cities and provinces of the state of Bavaria proclaimed their allegiance to this new “era of the end of Capitalism” as well.

It did not take long for this sham Soviet republic to be exposed as such, and the Rote Fahne fervently expressing the Communists’ desire to build a ‘real soviet republic’. Nürnberg’s central council had voted to oppose joining the Soviet Republic, hence giving the SPD government of Hoffman a last refuge in the state, and a base to organize against the frivolous revolution. Quickly, within just two days, the central councils in city after city were being overrun and rendered useless by counter-revolutionary students and soldiers. In Munich the SPD was split in half on a vote whether to support or abstain from the ‘Revolutionary Central Council’ government it had two days earlier encouraged the creation of, at the cynical initiative of Schneppenhorst.

Nonetheless, the new Soviet government, with Toller and his isolated Bavarian Independents at the helm, went about holding erratic meetings and signing declarations. With lots of discussions and ‘little positive constructive work’ as anarchist leader Mühsam later honestly reflected, discontent and confusion widespread among workers and soldiers. Levine’s biting critiques of the sham soviet republic very well held back little in his articles. Moreso, however, his articles heated up the Bavarian situation – a situation that was politically hopeless. Perfectly aware of the Freikorps organizing, the German Army’s rustling, and the SPD’s brutal consolidation of power throughout the country with Noske’s martial law over Germany, he agitated for a day where, “soon”, the actual Soviet Republic was to come.

One of the ‘sham’ Soviet Republic’s ministers sent a message to Lenin in Moscow, describing an almost magical unity of social-democrats, independents and communists. While this was not untrue for some of the parties’ members, it ignored the fact that this utilitarian unity of circumstance had in fact not been a long fought out, sober, and principled unity en masse, but a hair-brained and dysfunctional unity achieved among an absolute minority facing dire odds. The arming of the working class, it was concluded, was to not be pursued on a systematic level. Implicitly, though not explicitly, this was the case because people like Toller were aware of their weak situation, that the German political majority of Social-Democrats and conservatives held sway in Bavaria, even if it could not show its strength openly at the moment.

The aggregate of relentless school-boy communist agitation and speechifying for a ‘real’ council republic resulted in a peculiar situation during a worker council meeting at the Mathaeser Brau beer hall; being allotted the council meeting opening speech, Levine’s words against the sham council republic and Ernst Toller were very heated. Things escalated to such an extent, that, by the end of the evening, the Communists declared the central council to be deposed, arrested Toller in the beer hall and declared yet another “revolutionary” general strike. Attempting to disarm the revolutionary guard by the next morning, the Communists are then faced with a strong will by these decried “petty-bourgeois” revolutionaries. Fist fights break out between the communist, USPD/SPD, and other workers. A warning shot is fired into the ceiling of the Mathäser by the government’s revolutionary guard. The general tumult and threats of the revolutionary guard to arrest the communists, in turn, are only pacified by the released Toller, whose futile attempts the next day to agitate against the communist general strike cannot stop the inevitable dynamics.

Meanwhile, Levine, in a private conversation with Mühsam, stated that the council republic was thoroughly stuck in the mud. As a matter of course, he said, one should not let Hoffmann take over or negotiate, but should work to get the council government out of the mud. Instead of acknowledging the utter hopelessness of the situation, communicating it emphatically to the people and entering into negotiations for the survival of the revolutionary movement, the Communists and left Independent Socialists continued to sow illusions in the working class by agitating and organizing for a better, more “communist” council system.

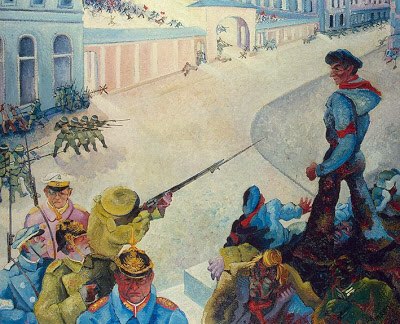

On the night of April 12th, Palm Sunday, the government of Hoffmann staged a Putsch against the Soviet republic. This was the instigator for a mass of outrage among workers. Mostly led by the KPD, workers took to themselves arms and ammunition. Spontaneously mixed together in action, workers from SPD, USPD and the KPD successfully disarmed a larger troop of counter-revolutionaries in a restaurant by noon of the next day. 9 After heavy fighting for the rest of the 13th, the revolutionary workers of Munich, led by the communist sailor Egelhofer, were the uncontested, and now armed, power in the capital city.

Thereafter, the revolutionaries disbanded the previously elected council leadership and formed a council’s Revolutionary Action Committee, with Levine at its head and two of its five seats handed to left Independents. Simultaneously, an advance of counter-revolutionary white troops marched towards Munich from the north, quickly cutting through scattered resistance. Ernst Toller caught word of the attack and, grabbing some comrades and supplies, headed towards the front in the nearest automobile. Reaching the suburb of Allach they encountered their men fleeing and a few isolated reds fighting back. Returning with heavy machine gun fire of their own and giving chase on horses, the red soldiers won back the main street and town of Allach. Roughly 10 kilometers and two towns had been won in two days of fighting before successfully driving back the white soldiers, beyond a creek and swamps by Dachau and the people disarming them in the town.

Declaring a six-day long strike for the workers to organize into a Red Army, the new central council, or Revolutionary Action Committee, was aware that, at this point, there was little way out except war. They had drawn blood, embarrassed the enemy (prideful German soldiers) by winning the battle of Dachau and formally organized a formidable Red Army, outnumbering all reactionary Bavarian military and paramilitary forces. Yet not even the seizure of power by the reds could change the ruling political balances in the land or the country; nor could the Soviet Republic of Bavaria convey the certainty of scientific socialism to the hearts and minds of Germans generally overnight through leaflets and propaganda, had they even had the organization or resources to carry out such campaigns. Bavaria was, in the overly-optimistic minds of a few (looking to its neighbor Austria and Red Vienna), to become the center for ‘carrying Bolshevism to Europe’. But as Levine had accurately described and predicted earlier, a truly revolutionary and communist Bavaria would be isolated. With none of its bordering states or nations continuing trade with the state, the economy would wither and its people starve.

In contrast to its two predecessors, the new government was at least able to introduce some routine under Levine’s leadership. However, this “routine” was strained to maintain a serious and confident character, given that there had been no preparations by the KPD to rule. Essential operations like telephone services were out of order after employees joined the bourgeoisie, with red soldiers wasting valuable days attempting to scrounge capable personnel, not just in idle telephone operations. At its headquarters in the former royal family’s Wittelsbach Palace, the Communist government was overrun by and felt compelled to listen to the fantastic plans of countless ‘dreamers and cranks’, in the hopes of winning administrative support and technical knowledge from the people. A task that apparently had been considered or planned for by the Communists as little as it had by the Independent Socialists.

Since March the miniscule KPD had refused cooperation with the USPD, on the grounds that that party was unsure of what it wanted and deluded by idealism. While this characterization by Levine was not inaccurate, the Communists themselves were just as deluded about the prospects of the revolution. In a speech to Berlin workers in 1917, Levine stated:

“The USPD hung around our necks like a millstone. . . We must put an end to this unnatural alliance, this marriage of fishes and young lions. We cannot possibly act the part of the whip that drives the independents to the ‘left’. How can there be an alliance between a whip and a donkey which digs in its heels and declares: ‘You can go on whipping, but I won’t budge.’ If we continue to ally ourselves with the USPD we shall be the donkeys!” 10

In reality, the Communists were just as much cripplingly dragged towards the earth by the USPD’s adventurist or conciliatory millstones on their own as they would have been if they were working side by side. It is clearly more effective to challenge someone’s views within institutions that purport to have a democratic culture when standing close to them, being able to reference commonly known principles and norms. The fact is that Levine failed to understand that while one may not be able to move a set Party anyway one wishes, one can influence its members and win influence over certain elements in a party’s leadership if that party is not yet clearly delineated for or against socialist revolution.

Long awaited, the final crackdown of the German reaction came upon Bavaria in the last week of April and the first week of May. Closing in around the capital, White Army forces, commanded by SPD military leader Noske from Berlin, committed many indiscriminate massacres with impunity. Executions of 30 Red prisoners in Starnberg on April 29th, a suburb 25 kilometers southwest of Munich, sparked outrage and tough fighting for the next few days on Munich’s western suburbs. While many of the most violent massacres were in fact perpetrated by the Freikorps groups, such as that of von Epp, it was the SPD leaders’ Army directives and ‘Execution Orders’ which provided the legal framework and policy for the ensuing slaughter. Lenin’s speech in Moscow on the 1st of May, proclaiming that the international day of Labor was being celebrated not just in Soviet Russia but also Soviet Bavaria, was not entirely up-to-date with developments.

A week-long civil and armed resistance by the Augsburg workers 60 kilometers west of Munich had been put down by the German Army on April 23rd. As a result of these experiences, White Army soldiers became increasingly frustrated at the guerrilla tactics of their enemies. In response to the grisly murders in the town of Starnberg, Munich city and Red Army commander Rudolf Egelhofer executed ten hostages from royal families and the Thule society, being held at the Luitpold Gymnasium in Munich. Used unanimously, by virtually all newspapers except the communist papers, as the only verifiable propaganda piece against the ‘bestial’ Soviet Republic, the unfortunate executions proved further fervor for the hatred of German Army soldiers against the ‘Bolshevik hordes’, leading to, among many others, 53 Russian POWs being murdered in the tiny suburb of Gräfelfing. It had been the German Army which introduced the execution of hostages and prisoners of war in the course of WW1. If anything, the Luitpold executions showed the weakness and lack of authority which the Red Army command had. For 30 Reds murdered in Starnberg by the whites (among many others), only 10 Thule Society reactionaries were executed. Hardly a punishing response.

Nevertheless, resistance against the whites was fierce, especially in Dachau, where the Red Army had proven itself capable of winning in battle. By April 30th, however, Egelhofer had reversed the ordered offensive from Dachau to take the adjacent northern German airport of Schleissheim and ordered a complete retreat to the city. More and more red officers at this point had defected, discipline within the Republic’s forces weakened by the failing course of events. Many returning soldiers from Dachau simply abandoned their post and duty due to demoralization at the ongoing political disputes between the USPD and KPD.

With the entrance of the Army into the city, pockets of armed resistance within the small area of Munich’s city’s limits lasted for three days, seeing bomber planes, artillery, flamethrowers, and conventional military and machine gun weaponry unloaded on the last fighters in the city. For weeks, public opinion was ruthless towards the ‘Spartacists’, with Army soldiers beating and killing many thousands, many victims completely unrelated to the Soviet Republic’s organization or its defense – Red soldiers, Catholics, Jews, Russians, older women, younger women, and older men, it did not matter to the German soldier. Once the rules of war were unleashed by the nation and turned inward, it proved hard to stop the killing, for another generation.

“Everywhere there were long moving rows of arrested workers, beaten bloody and bruised, with their hands in the air. To their sides, behind and in front of them, soldiers marched, yelling when a tired arm wanted to fall, rifle butting their ribs, thrusting blows with their fists on those trembling. […] They are all my brothers, I thought contritely. […] They had all been dogs like myself, had to submit and cower their wholes lives, and now, because they wanted to bite, they are beaten to death. […] For days, all one heard were the arrests and executions. […] The Soviet Republic had ended. The Revolution was defeated, the firing squads at work industrially…” 11

The German November and Bavarian revolutions had drawn to it large segments of the population which had been pushed to their brink physically and mentally through the experiences and consequences of the war, returning to an incredibly unequal and corrupt capitalist society. Many participants had little theoretical education on or understanding of socialism. With the dragged out failure of the revolution, its eventual bitter defeat and the physical destruction of its strongest leaders, many of its followers sought promise and leadership elsewhere. Enlisting as a Red Army soldier in April for the communist Bavarian Soviet Republic, and fighting for it, Julius Schreck became a close confidant of Adolf Hitler as well as the founding leader of the SS. Schreck went on to practice his revolutionary experience as an organizer for the Nazi’s infamous 1923 ‘Beerhall Putsch’ in Munich. 12

The cooption of the German worker movement’s aesthetic and socialist rhetoric for Fascism was not an invention of Hitler’s. Rather, it came from the cynical businessmen of the Thule Society and other bourgeois in the form of the DAP (German Worker’s Party) and was a clear tool used by these terrified gentlemen to reign in the mass discontent among the people. In fact, instead of joining the Thule Society inspired Freikorps groups which were mobilizing and attacking the Soviet Republic and Communists (such as Röhm, Wessel or even Strasser), the little clues left of Adolf Hitler’s activity point to an undecided man; one who participated in the revolution and who in July of 1919 was told to infiltrate the DAP for the German military who kept him employed. The rest of that story is well known.

Eugen Levine’s comment that there was too much focus on “high politics” (a reference to prolonged USPD/anarchist negotiations with the majority SPD and bourgeois representatives) was a curious comment in retrospect and one which, among other actions, shows his sectarianism and leftist deviation. The Munich Communists had a deep-seated tradition of tailing party-advertent anarchists who, as Hans Beyer says, might have been subjectively ‘real’ revolutionaries, but whose actions objectively thwarted the survival and success of the revolution. It was, in fact, the culturally dominant political trend of socialist idealism within the Munich left which was responsible for many of the aggressive and fatal delusions so deeply entrenched in the minds of the Bavarian militant minority, not the realistic “high politics” of “moderate” Independent Socialists like Felix Fechenbach.

An unfortunate comment by Munich’s later Communist Party chief, Hans Beimler, addressed to the Nazis, that ‘We will see you again in Dachau!’, was sneeringly pounced upon and paraded by the Bavarian bourgeois press when their Heinrich, Heinrich Himmler, founded Nazi Germany’s first concentration camp in the bastion of Bavarian socialism, Dachau. In 1933, on his way to being detained to the concentration camp, Felix Fechenbach was shot by the SS for ‘attempting to escape’. Thankfully history is not static, however, and the final words at the camp were spoken from behind an assembly of Springfield and M1 Garand rifles. Yet, the real story and significance of Dachau have, as a consequence, yet to be told.

The tragic destiny of all the promising revolutionary leaders – from Levine, Egelhofer, Fechenbach to even the young Toller, but especially the thousands of nameless Republican defenders who paid the ultimate price, as well as innocent bystanders – should not be ours to embrace and elevate, but one to mourn, remember and learn from. Revolutionary adventurism and immature politics, both outside, but especially within its ranks, was not thoroughly confronted by the KPD, making the consequences of failing to circumvent and warn of the pompous and sardonic schemes of the willing and unwitting agents of capital long lasting and painful. Unlike few other places and moments in the chronology of the worker’s movement, the revolution of Bavaria displays clearly the importance of an intelligent socialist politics, and ought to be heeded as an ominous warning and lesson of history.