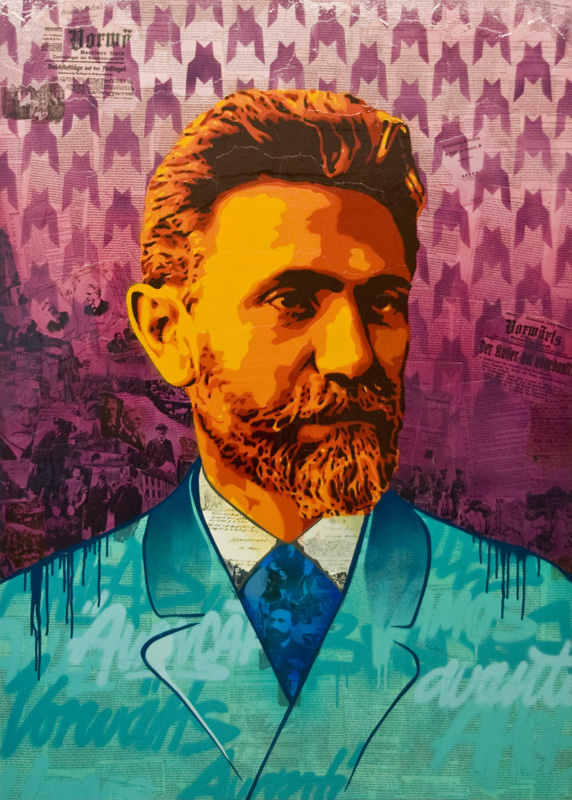

Mike Taber weighs in on the Kautsky debate happening at Jacobin Magazine, responding to Eric Blanc’s text Why Kautsky Was Right (and why you should care). Taber sets the record straight on Kautsky’s strengths and weaknesses and Blanc’s uncharitable reading of Leninism.

Eric Blanc is a talented Marxist historian and activist, with a reputation for questioning accepted wisdom. While one may not always agree with all of his conclusions, Eric’s works generally have a refreshing quality that can only be welcomed.

That freshness, however, is not in evidence in his latest article, “Why Kautsky Was Right (and Why You Should Care)” published in Jacobin. The main point of the article is to defend Karl Kautsky’s perspective of a “democratic road to socialism” as against a supposed Leninist “insurrectionary strategy.” In addition to presenting a false framework for the debate, the article strays from Kautsky’s actual record and legacy. It also presents a caricature of “Leninists.”

Good Kautsky / bad Kautsky – Which is it?

There are many positive aspects of Kautsky’s early record: his defense and popularization of Marxism; his opposition to Eduard Bernstein’s revisionism; his internationalism; his opposition to imperialism and colonialism; his enthusiasm for the Russian Revolution of 1905. But Eric mentions none of these points. Instead, he focuses exclusively on the question of the “democratic road to socialism.”

Blanc draws a distinction between Kautsky’s perspective before and after 1910. Kautsky is presented as caving in that year to the opportunist wing in the German Social Democratic Party, reversing many of his key strategic ideas and moving toward reformism.

It’s certainly true that Kautsky backtracked on a number of issues in the years around 1910, and especially after 1914. But the strict division into what one might call a Good Kautsky (before 1910) and a Bad Kautsky (after 1910) does not stand up to reality and is an obstacle to assessing his legacy. Such a dichotomy ignores how aspects of the early version may be found in the later one. It also conveniently implies that all the unsavory things Kautsky did or said after 1910 – and particularly after 1914 and 1917 – can simply be ignored as irrelevant to Eric’s thesis about “why Kautsky was right.”

The reality is much more complex.

First of all, Blanc’s formulation “Kautsky’s case for a democratic road to socialism” is misleading. One will look in vain for such a concept in the three main books Kautsky wrote prior to 1910 that outline his perspective of revolutionary change: The Class Struggle (1892), The Social Revolution (1902), and The Road to Power (1909).

It’s true that in these books there was unclarity as to how a socialist transformation would occur. But they all nevertheless argue sharply against the perspective of evolutionary change through the capitalist political set-up. The role of democracy, as Kautsky put in The Social Revolution, is “as a means of ripening the proletariat for the social revolution.” The quotations that Eric cites from these books show the exact opposite of what he’s trying to prove.

The first place I’m aware of in which Kautsky outlined the idea of a “democratic road to socialism” was in his 1918 work, The Dictatorship of the Proletariat, as a counterposition to the October Revolution and the Bolsheviks in Russia.1

So the very aspect of Kautsky that Eric Blanc admires most – his “democratic road to socialism” – comes from the Bad Kautsky of post-1910.

Secondly, even though the early Kautsky ably defended important aspects of Marxism, he had a longstanding tendency of adapting to reformist and opportunist currents. The best example of this was in 1900, around the question of Millerandism.

Alexandre Millerand was a French socialist who entered the ministerial cabinet of the bourgeois government of France in 1899. This act led to debate throughout the world socialist movement, given that socialists had always opposed such ministerial participation. At the Second International’s Congress of 1900, it was Kautsky – the Good Kautsky – who introduced a resolution condemning socialist participation in bourgeois ministries under “normal” circumstances but leaving the door open to it under “exceptional” ones. “If in some special instance the political situation necessitates this dangerous expedient,” the Kautsky resolution stated, “that is a question of tactics and not of principle.”

This fence-straddling position was met by a counter-resolution put forward by Enrico Ferri and Jules Guesde, opposing such participation under all circumstances. Even though the Kautsky resolution was eventually adopted, its ambiguities and the dissatisfaction thereby engendered led to its repeal at the next Second International Congress. The resolution adopted at the 1904 Congress, defended most forcefully by August Bebel, condemned all socialist acceptance of ministerial posts in capitalist governments.

‘Leninists’ vs. Leninists

In many of Eric Blanc’s articles, a constant target is the standard historical narrative. As Eric has frequently shown, such narratives can over time become schematized and fossilized, posing an obstacle to clear thought. However, the latest article’s depiction of “Leninists” is largely based on exactly such a standard narrative. Let us examine a few quotes from the article:

“Leninists for decades have hinged their strategy on the need for an insurrection to overthrow the entire parliamentary state and to place all power into the hands of workers’ councils….

“Leninists have rarely grappled with these facts [i.e., workers’ reluctance to “replace universal suffrage and parliamentary democracy with workers’ councils”], let alone provided a compelling explanation for them….

“Leninists have generally been reluctant to proactively fight for major democratic reforms because they seek to completely illegitimate the current state.”

The standard narrative of a Lenin with a fanatical obsession with revolution and insurrection is one I’m quite familiar with, from my Cold War school textbooks in the 1960s. But it’s entirely false.

First of all, Lenin and the early Communist movement never put forward an “insurrectionary strategy.” Their strategy was aimed at mobilizing the proletariat and its allies around the fight for their class interests, and to direct it toward the conquest of political power and the overthrow of the rule of the bourgeoisie. In this, they utilized all methods. They also recognized the reality that socialism could not be reformed into existence; a revolution was required to overturn capitalism’s political apparatus. This revolution would lead to the dictatorship of the proletariat, based around a soviet-type system of workers’ democracy.

There is no distinct “Leninist strategy of insurrection” – any more than there’s a Leninist strategy of strikes, of demonstrations, of picket lines, of protest meetings, of study circles, or of fund appeals.

There indeed was such an “insurrectionary strategy,” but it comes from Blanquism, not Leninism. Louis Auguste Blanqui was a dedicated and admirable French revolutionary from the nineteenth century, whose followers did come up with such a perspective. But Lenin argued strongly against that view.

The idea that the proletariat could not achieve revolutionary change through the existing state structure, but only through its overthrow, comes squarely from Marx and Engels. It was a conclusion they drew from the Paris Commune of 1871.

Even more astounding is Blanc’s contention, quoted above, that “Leninists” have been reluctant to fight for democratic rights. Such a blanket and unsubstantiated assertion run counter to all evidence.

True, one can unquestionably find some self-styled Leninist groups and parties that undervalue this fight. But one cannot find such undervaluing in Lenin, Trotsky, the early Comintern, or many others who look to that tradition.

The entire history of the Bolsheviks’ struggle in Russia shows the opposite of what Eric claims. In the years leading up to 1917, their agitation was centered around the so-called “Three Whales of Bolshevism.” These were the eight-hour day, confiscation of the landed estates, and a democratic republic. During 1917 itself much of their agitation was also based around democratic demands.

Following the revolution’s victory, the early Communist movement followed in this tradition, as demonstrated clearly in the series of books on the Comintern edited by John Riddell.

Likewise, in modern times, those who look to Lenin’s legacy and tradition have been active in the civil rights movement, the fight for women’s rights, freedom for political prisoners, immigrants’ rights, and for many other democratic issues. In fact, the majority of struggles in the imperialist world today are around democratic demands.

The workers’ government – fact and fiction

Eric’s comment about the early Comintern is also wrong. He writes:

[T]he most perceptive elements of the early Communist International began briefly moving back towards Kautsky’s approach in 1922–23 by advocating the parliamentary election of ‘workers’ governments’ as a first step towards rupture.

That statement is factually inaccurate. The Fourth Congress of the Communist International in 1922 indeed held a discussion on the workers’ government question and adopted a resolution on it. But nowhere did that Congress suggest that a workers’ government could be established by “parliamentary election,” as Eric claims. Quite the contrary.

In this resolution analyzing variants of workers’ government, it begins with two variants that it calls “illusory workers’ governments”:

“(1) a liberal workers’ government, such as existed in Australia and may exist in Britain in the foreseeable future. (2) A Social-Democratic workers’ government (Germany)…The first two types are not revolutionary workers’ governments at all, but in reality hidden coalition governments between the bourgeoisie and anti-revolutionary workers’ leaders.”2

As can be seen, such governments were certainly not “advocated.”

A “genuine workers’ government,” the resolution stated, “is possible only if it is born from the struggles of the masses themselves.” The significance of a “purely parliamentary combination” lies in that it can “provide the occasion for a revival of the revolutionary workers’ movement.”3

Moreover, the workers’ government concept largely came out of the experience of the German Communist movement. Following the right-wing Kapp Putsch of 1920 that aimed to overturn the German bourgeois democratic government, workers engaged in probably the most complete general strike in history and began to form armed workers’ detachments. Out of this upsurge, a call was made for a government of all the workers’ parties. After some debate, the Communist Party gave its support to that initiative.

So the workers’ government (and later the workers’ and peasants’ government) was directly linked by the Comintern to revolutionary struggle – not merely to the triumph of workers’ parties in bourgeois elections.

Yes, there have been examples where working-class electoral victories – and the reactions to them by the ruling class – have led to the onset of revolutionary struggles. Revolutionaries and Leninists have never discounted this possibility. The example of Finland that Eric cites – in which a working-class electoral victory led to the onset of a revolutionary struggle in which workers had an opportunity to take full power into their hands – is a demonstration of how this can occur. But it takes a stretch of the imagination to squeeze the Finnish revolution and civil war into the framework of a “democratic road to socialism.”

The Russian Revolution and the electoral road

Blanc labels the October Revolution of 1917 in Russia as “a revolution that toppled an autocratic, noncapitalist state, not a parliamentary regime.” This is not entirely true.

That statement may be an accurate depiction of the February 1917 Revolution that overthrew the tsarist regime. But it is completely inaccurate when describing the October Revolution that toppled the Provisional Government – a capitalist government, not a “non-capitalist” one. Furthermore, a democratically elected body did exist prior to October, but it wasn’t a bourgeois parliament; it was the Soviets, elected by workers and soldiers, in which the Bolsheviks obtained the majority. During the course of 1917, Lenin and the Bolshevik leaders had repeatedly stressed that they would respect the democratic will of the majority of working people, registered in the Soviets. The October insurrection that overthrew the Provisional Government was a defense of this working-class democratic will against an attempt by the government and counterrevolutionary forces to suppress the Soviets. In this sense, the October Revolution might indeed be seen as an example of the “democratic road to socialism,” although the opposite of Kautsky’s conception of it.

While electoral victories can on occasion open the door to revolutionary struggle, there is no example in history where a transition to socialism was successfully achieved entirely through peaceful and electoral means.

Obviously, such a peaceful transition would be preferable to revolutionary upheaval. But has there ever been a ruling class in history that has calmly and peacefully surrendered its power? Will the bourgeoisie come to shake the proletariat’s hand and say, in chivalrous fashion, “You won fair and square. Here are the keys to our government and to our industries. Good luck.” No, I don’t think so!

Asserting that the electoral and evolutionary path to socialism is not possible does not in the slightest mean discarding all possibilities and openings that elections and election campaigns can provide to the working class and its parties. But as the examples of Finland, Spain, Chile, and other places show, sowing illusions among working people in a purely “electoral road to socialism” is a recipe for disaster and defeat.

In this reply, I have deliberately avoided tying these historical arguments into current debates about Bernie Sanders, work inside the Democratic Party, electoral approaches, and so on. The historical record of the socialist movement must never be distorted in order to serve a particular political agenda. To do so would be a disservice to the many thousands of young people attracted to socialism today.

This was originally published on John Riddell’s blog here.

Mike Taber is preparing a volume collecting together all the resolutions adopted by congresses of the Second International between 1889 and 1912. He is also editor of “The Communist Movement at a Crossroads: Plenums of the Communist International’s Executive Committee, 1922-23” and co-editor of “The Communist Women’s Movement 1920-1922.”

- All books by Kautsky that are mentioned can be found on Marxists Internet Archive.

- John Riddell (ed.), Toward the United Front: Proceedings of the Fourth Congress of the Communist International 1922 (Historical Materialism Book Series, 2012), p. 1160-1

- See Comintern “Resolution on Workers’ Governments” on this website for more information.