Renato Flores discusses the privatization of scientific knowledge and examines efforts of revolutionary movements to democratize this knowledge to help develop a communist approach to science.

I

The famous quote “knowledge is power” can be read in two ways. The first is that knowledge is power over nature: it gives us the ability to free ourselves from natural necessity. Knowledge is Promethean, it is the stolen fire that cooks our food and keeps us warm, the vessel that gave us civilization. The second way to read this quote is more sinister: knowledge is power over others. Advanced weaponry allowed Europe to dominate the world for centuries. Surveillance technology allows the modern state to respond to potential threats within before they become actual. Domination can be subtle: knowledge of law is reserved to lawyers, an elite professional sector of society. This means that poor people are still at a disadvantage in court because their access to knowledge is limited, even if one assumes the state to be neutral.

Marginalized communities become either mystified or suspicious of science, if not both because knowledge is used to further their oppression. But this misses the question- how was knowledge of advanced weaponry acquired? And why was it exclusive to some peoples? The popularized history of science is that a few Great Minds produced all knowledge while in the service of the State. The West was made great by Galileo’s experiments in the Venitian Arsenal and Henry the Navigator’s School of Sagres. The scientific wit of a Great Few fits perfectly in a Darwinian story of the world. Western civilization dominated the world because they were (led by) the smartest, and thus the fittest, while the rest of the world was stuck in primitive mysticism. The White man’s burden was to bring knowledge to the world.

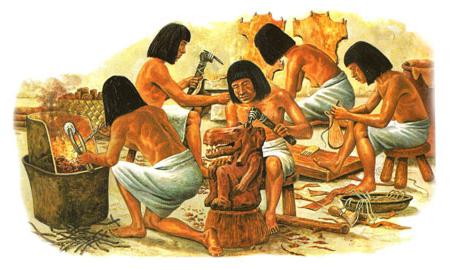

But this history of science is a sanitized and distorted one of its material realities. Knowledge is intimately linked to labor and practice. People low in the pecking order often generate it, and it is appropriated and stolen by more reputable people or institutions. Onesimus, the slave who used ancestral African knowledge to introduce inoculation against smallpox to the New England settlers is just one example among many. We only remember his name because his owner, Cotton Mather, revealed the source of his methods. But the list of forgotten names is immense: entire fields such as pharmacology have a deep debt to the Aztecs and Incas.

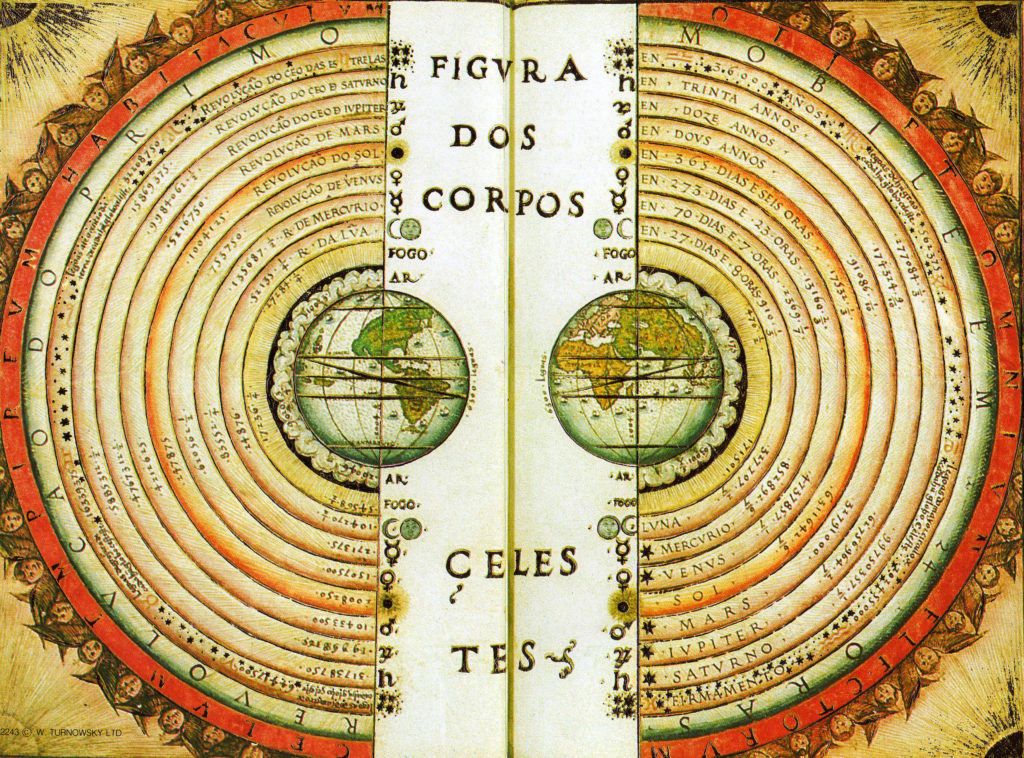

A full historical account of this appropriation-privatization of science is given by Cliff Conner’s People’s History of Science.1 Ancient scribes developed more advanced counting systems to work more efficiently, while prehistoric builders were forced to reckon with notions of geometry. With the rise of the centralized state, the power of this knowledge became more and more reserved for the exclusive use of the ruling classes. And with this privatization, knowledge was no longer linked to practice and idealism sneaked back in. The five regular polyhedra became sacred geometry. Astronomers doubled as priests to make predictions about the harvest, while the lower castes continued with their lives, now beholden to the knowledge their forefathers had generated.

The culmination of ancient idealism is Plato’s strict anti-empiricist program. The elevation and sacralization of Truth reached its extreme in The Forms, located outside the material sphere and only accessible through a learning process that would bring reminiscences of past lives. This program was not very conducive to future research: once the “official” line had been revealed, it was impossible to challenge. Aristotle, Plato’s greatest disciple, had to retreat from pure idealism to reincorporate the role of observation and experiment. But the Aristotelian system still suffered from much apriori reasoning.

Even more important for our story is that Plato was the father of an elitist cast of scientist-philosophers: the Academy. In Plato’s ideal Republic the philosophers were the kings while the other castes would only have access to a vulgarized and controlled version of the Truth. Aristotle’s Lyceum did little to change that fundamental idea of an elite which was entitled to rule because they were educated in Virtue. And through continuity and rupture, this germinal idea survives to our present day. The Hellenistic Academies passed the torch to the Christian church, the first replacement in the long chain that leads to the present.

After the fall of Rome, Europe went through a period of stagnation, where knowledge was lost. This was followed by the scholasticism of the Middle Ages, where both translations of the old, and new works from the Islamic world were received through reconquered Spain. But even scholasticism reduced the academic search for truth to commentaries of philosophers, in particular Aristotle and Averroes. It was a largely idealistic pursuit, and the Averroists were derided by Petrarch as people who “had much to tell about […] how many hairs are there in the lion’s mane”, yet “would not contribute anything to the blessed life”. While Petrarch was formulating the humanistic critique of scholasticism, as much can apply to a materialistic critique- scholarly knowledge had little to say about practical life.

In the meantime, the accumulation of material knowledge persisted outside the European sphere,. The scientific revolution could have seen its birth in the works of Ibn al-Haytham. He discovered principles of optics by combining Aristotelian systemic thinking and careful experimentation. Driven by his experience as a civil engineer, al-Haytham established one of the first known formulations of the scientific method. But the Islamic world was let down by one component. Even if European monks remained far from the generation of material knowledge, the Church and the Universities provided a structure for scientific formalization and institutional memory which was absent in the Near East. The new Academy was waiting to be born, longing for the replacement of scholastic disputations by practical treatises.

II

The Zilsel Thesis was one of the first attacks against the Official History of Science.2 Zilsel claims that the Scientific Revolution was not just the product of Great Minds. It happened as two currents converged: the experimenting artisans generated the Knowledge, while sections of the Academy provided the method to organize it. The same way that the Social Democratic Party was the merger of the worker movement and socialist theory brought from without, Science was born when the rebels of the intelligentsia decided to merge their methods with the practical knowledge of the artisans. Francis Bacon supplanted the Aristotelian Organon, the par-excellence tool of scholasticism with his own Novum Organon, a new way to systematize knowledge. Bacon realized that the university-based sciences “st[ood] like statues, worshiped and celebrated, but not moved or advanced”. His project to revitalize the sciences passed through systematizing the collected experience of craftsmen to alter nature.

Bacon’s vision of the merger was twisted. The two currents would not stand equally. Instead, his utopian New Atlantis laid out a comprehensive vision of a futuristic and sanitized scientific establishment which had enthroned itself by appropriating the knowledge of the lower classes. The new philosopher-kings were in many ways the same as the old, they just operated under a new method. They had a monopoly on the access to systematized knowledge, and even had power over the State: the Scientists of the House of Solomon were even entitled to keep scientific findings for themselves. This was not a new idea – Plato had already envisioned that the populace would be taught a vulgar vision of the world, adequate to fulfill their predetermined role. But the Baconian monopoly on knowledge would now be real power: it was based on materially applicable Truth with that could bind and dominate; and not on endless disputations and annotations on the origin of the Universe.

Bacon’s ideas represented that of the nascent bourgeoisie. Despite his utopia, Bacon was no revolutionary. He was a faithful servant of the English court and was laying out a blueprint for strengthening it. His project was one of a passive revolution, which replaced one elite with another one. But during the 16th and 17th centuries, the future of Europe was contested. The Catholic church’s monopoly was finally broken, and radical and utopian projects floated in the air. Another utopian proposal, Campanella’s City of the Sun dignified all work, allowing artisans and peasants into the dreamed city. Knowledge was shared: the walls of the city were pictures of a painted encyclopedia, openly shown to everyone. But Campanella relied on an elitist conspiracy to achieve his utopia and ended up in jail most of his life.

The only radical scientist of the time to build a substantial movement behind him was Paracelsus. Rising from his experience as a medic in the mines, he gave a scholarly voice to the artisanal understanding of medicine, opposing the existing distinctions between the lowly manual surgeons and the high physicians that never touched a body. Paracelsus supported the Radical Reformation and the German Peasants War. He inaugurated a movement of folk healers for the People, which would democratize access to medicine. The Paracelsian movement would only grow after Paracelsus’ death. It was revolutionary because it sought to break the monopoly on knowledge and democratize its power. Paracelsianism would become one of Bacon’s main targets of attack, he rightly seen as a dangerous threat to the established order.

The torch of a rebel science was carried forward. In a pattern we will see emerge, every great social revolt posed the question of knowledge democratization. The Diggers, the most radical faction of the English Revolution also proposed a radical education program. Their leader, Gerrard Winstanley, demanded that an elected non-specialist would teach science in every parish and that this knowledge could be applied to the problems of everyday life. But the routing of the radicals in the English Revolution cut short this program. Baconianism would prevail, and the use of science against the people became routine. A new scientific establishment was formed in the Royal Societies, partly aristocratic, partly bourgeois. As the new Organon triumphed over the old, knowledge was accumulated, if not downright stolen from the newly colonized people. Capitalism expanded, and Science was tasked with the quest to invent more efficient machines that would replace skilled workers and increase productivity. The Enlightenment was a time to celebrate reason’s role in emancipating humanity from its immaturity. But as technology became a method for de-skilling and disciplining the workforce, Rousseau would proclaim that progress was making man less free.3

The bourgeoisie was winning the battle for ideological hegemony, and the Cartesian mechanistic view of nature became a common stance. The period leading up to the French Revolution saw the publication of Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopedia, a landmark for the ascendant bourgeois Science. It was meant to change the way people thought. It actively challenged religious authority and was condemned by the Catholic church. The Encyclopedia also celebrated artisanal knowledge and sang the praise of artisans. But the twisted merger of bourgeois science repressed this side of the equation. Even as their practical knowledge was elevated, artisans themselves were excluded from the scientific community.

The French Revolution would throw the tensions between artisans and the Academy in the open. After the outbreak of the revolution in 1789, the artisans organized in free associations which challenged the Academy’s monopoly on Science. These free associations sought to democratize access to knowledge making it available for everyone. But now that the monarchy was gone the newly-freed bourgeois and aristocrats of the Academy were looking to further consolidate their powers over what was acceptable Science. This brought an inevitable conflict. The Condorcet proposal, to make the Academie an even more elitist institution, was fought tooth and nail by the sans-culotte artisans. As the revolution radicalized in 1793, the sans-culottes obtained a temporary victory. The Académie was shut down because it was rightly considered an undemocratic and aristocratic institution. Baconian science was on the run, and a popular science had its first real triumph for a brief period. Thermidor would bring an end to this, restoring the academy on even more elitist grounds.

The Thermidorian academy would accelerate specialization. Science would slowly but surely be put at the effective service of capital, while still paying lip-service to educating the lower classes. Passion, feeling, and humanism were exiled from the academy. The production of knowledge became a slave to profit while masked by scientific neutrality. However, this was just one of the possible futures. As the absolute power of the Church and the King collapsed, the French 18th century also saw rampant speculation on new world-systems and other ways of organizing knowledge. After Rousseau’s diatribe against progress, his intellectual heirs sought to recover a natural philosophy that merged all knowledge and put it to the use of mankind, rather than the use of Capital. They demanded that science must have a moral component if it was not to amount to raw weaponry in the hands of the oppressors. The common Newtonian-Cartesian paradigm of studying and understanding phenomena in total separation was in accordance with the bourgeois primacy of the individual over the collective. In opposition to this, Bernardin de-Saint Pierre best formulated an anti-reductionist science. He rebelled against the tendency to compartmentalize and specialize, highlighting the interconnectedness of the world. But his new system was coldly received by an Academy which was increasingly focused on the capitalistic use of science. Napoleon himself told him to learn calculus and to come back.

As capital expanded, so did the working class. Utopian Socialists such as Saint-Simon attempted to alleviate the problems of capitalism by proposing a series of solutions from above. Saint-Simon saw in the industrial class the future transformers of the world, but for this to happen they would have to be properly organized. He proposed a societal organization of strict meritocracy, where scientific investigation would serve as a rational basis. Comte followed his steps and developed them further.4 His “scientific” positivism was something more akin to a total cosmovision where science would be used at all levels to organize society. Scientifically enlightened men should govern the uneducated, and provide mechanisms of societal cohesion for the universal wellbeing. In Comte’s Utopia, the intelligentsia would govern for the good of all. Science was for the People, but not by the People.

Comte’s writings attempted to avoid the fragmentation of knowledge into infinitely divided fields. But in his philosophy, there was still a gap between doctrine and practice. His complicated and ahistorical elaboration of the three stages of science was just a stopgap. Comte was unable to appropriately discuss the class implications of research programs. This would have to wait until the Marxist Philosophy of Science, inaugurated by Joseph Dietzgen’s writings and Engels’ Anti-Dühring and Dialectics of Nature. In contrast to bourgeois individuality, the workers’ movement approached things from a collective standpoint. And as the Second International took shape, Marxists widely polemicized about their cosmovisions. A full account of this is impossible, and Helena Sheehan’s Marxism and the History of Science provides invaluable details and names on the many Marxist philosophers up to the 1970s which strove to restore a holistic use of knowledge. The sanitized Cartesian-Newtonian world system was longing to be replaced so that science could advance further.

III

In the early 20th century, two Marxist authors stand out for the originality of their educational program. They both put forward the need for the proletariat to generate its own modes of thought before the revolution, centering the role of proletarian intellectuals in opposing the dominant ideology. They both saw how the bourgeoisie had formulated their own culture through Bacon and Diderot before taking power, and aspired to model the upcoming proletarian revolution in a similar manner.

While this idea is often associated with Antonio Gramsci, before him there came Alexander Bogdanov. Bogdanov was not only a physician but also a philosopher and a science fiction writer. Similar to the French revolutionaries, he formulated a two-fold program in pre-revolution Tsarist Russia based on a new form of education and a novel world understanding. One of his crowning achievements, tektology, was his proposal for organizing systems ranging from society to knowledge. His view of an interconnected and perfectly organized world was a new spin on an anti-reductionist science. Tektology went against Engels’ dialectics in some ways: Bogdanov sought to analyze how systems could remain in dynamic equilibrium instead of in constant dialectical evolution. It was a forerunner of the current systems theory and cybernetics.

Bogdanov was an original thinker, laying out a comprehensive vision for a Working-Class Science. He understood that the class character of science lay in “its origin, designs, methods of study and presentation”.5 Bourgeois science was only built for the benefit of Capital, while a working-class science would emphasize collectivity. Bogdanov’s new science would be an “organized collective experience of humanity and the instrument of the organization of the life of society”.6 The workers had to develop a new epistemology, throwing out the old one, and he thought that art could be an inspiration for this. Lenin polemicized against Bogdanov in Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, considering that his focus on science as collective experience went against strict Marxist orthodoxy. But Lenin’s Materialism and Empirio-Criticism contained many crude assumptions about Nature from which he would later walk back from.

Bogdanov proposed to organize the new science in a Workers’ Encyclopedia, which would be a harmonious system instead of just a summary of concepts. The Workers’ University would provide courses on the new unified science and serve as an education point for revolutionaries. A first attempt at a Workers University took place in Capri, where a small cohort of students were lectured by Bogdanov’s intellectual group in the hopes that they would form the nucleus of a proletarian culture. This turned out to be a very top-down approach and ultimately broke down as only one group of students graduated. While a laudable program, it was disconnected from the material realities of the time.7

Even if Bogdanov was a founding member of the Bolsheviks, he came further and further apart from Lenin. Bogdanov’s primacy of cultural Revolution crashed against Lenin’s program for revolution. The difference kept on growing during the prelude to revolution, Bogdanov, and others wanting immediate revolution and no participation in the Duma while Lenin saw parliamentary work as essential in a period of revolutionary ebb. When the political differences between both ended up being too large, Bogdanov was expelled from the Bolsheviks.

After the February revolution, the ideas of Bogdanov and co-thinkers like Lunacharsky saw a revival in the form of Proletkult, an organization that would create a new proletarian culture for the new workers’ state.8 This organization sought to be completely autonomous of the party and the state, something intolerable at a time of Civil War. Eventually, it was brought under heavy control of the party and later disbanded as the Bolsheviks centralized power.

Due to his break with Lenin and expulsion from the Bolsheviks, Bogdanov has been largely forgotten by history. In another era, he would have rightly occupied a high place in the intelligentsia. But even as he formulated a working-class science and a radical new societal organization, in his practice he ended up reproducing many of the actually existing structures of the Academy. His attempts to start a Workers’ University brought workers from all over Tsarist Russia, but layed on a rigid framework. A few lecturers, him included, would provide their vision on what the workers should be doing, instead of linking the curriculum to the material needs of the students.

Proletkult was in many ways an improvement. Because it was able to organize in the open it had stronger involvement of workers, numbering at eighty-four thousand members at its peak. Because the ultimate target was the creation of a new workers’ culture through the abolition of the intellectuals, a transitional period was necessary. Even if some programs were worker led, Proletkult was predominantly guided by Bolshevik intellectuals. These provided a guiding thought what on proletarian culture was, and how ideal workers should relate to another.

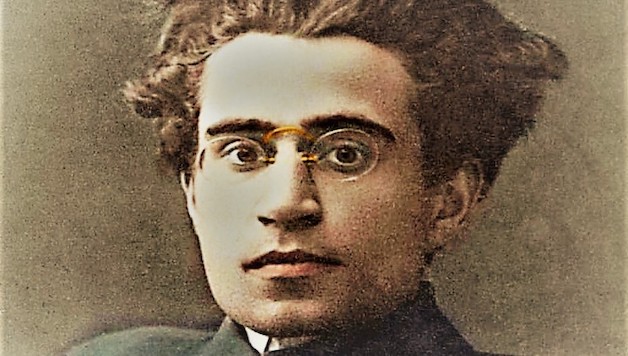

Proletkult was a massive organization in a time of convulsion, and the problems within it cannot be attributed solely to Bogdanov’s prescriptions. Its rifts appeared in a period where the workers had taken power without having produced a proletarian culture. Some of these fault lines were transcended in Gramsci’s approach to the role of proletarian intellectuals. Gramsci’s philosophical program was deeply marked by being a close witness to the rise of fascism and the failure of the Italian left to take power after the factory occupations. He is well known because of his analysis on how the dominant ideology softly persuaded people in accepting the status quo, the so called “hegemony” of thought. He set out to understand how this hegemony was created, and reproduced by the intellectuals and society.

Gramsci understood that while the traditional intellectuals of the Academy saw themselves as an elite functioning aside from society, they were embedded in the system of production and were naturally conservative in order to preserve their privileges, even if some would defect to the workers and were proletarianized themselves. But these intellectuals were not the ones bringing the dominant ideology to the masses. Another type of intellectual existed alongside the Academy: the organic intellectuals. They were consciously embedded in the process of production because they managed and coordinated the economic system. In doing so, they propagated the world view of the ruling classes throughout the population.

To change the world, Gramsci, like Bogdanov, required the creation of a new generation of organic intellectuals from the proletariat. Gramsci saw the potential in everyone, writing that “all men are intellectuals”. They just needed to be given the means to actualize this potential. Their schooling must relate to everyday life and transform them into individuals capable of thinking, studying and ruling. These proletarian organic intellectuals would collect and systematize folk knowledge to represent the excluded groups of a society. Gramsci’s intellectuals would fight a cultural war, to generate an alternative system of perceiving the world. With Gramsci’s incapacitation through incarceration, he was never able to put his program into practice. His notebooks are incomplete, and naturally invite speculation of what he meant. We cannot speculate how his Italian Proletkult would have looked like and what problems it would have come across.

Unlike Bogdanov, who saw the task of proletarian revolution as immediate, favoring a rapid political seizure of power by a Proletarian dictatorship, Gramsci’s organic intellectuals would have a long war ahead of them, synthesizing and spreading a proletarian hegemony before the revolution. Because of Gramsci’s prediction of a long “war of position” that lay ahead, he has often been read in a reformist light. If intellectuals had to occupy more space within the existing institutions, the question of power could be indefinitely be put off. Gramsci, as Marx and many others, was tamed.

Alongside these two thinkers stands Christopher Caudwell, who did not formulate an educational program but wrote much on Science. Caudwell is an underappreciated figure, a British Marxist who died very young in the Spanish Civil War. He, like many others in his time, understood that bourgeoise science was reaching its limit, and that technological progress would mean each successive day would be more alienating, rather than empowering. Only a communist society would cure the maladies of science. His communist utopia was one where the intellectuals would learn from the workers, as much as the workers would get guidance from the intellectuals.

Caudwell saw science in a similar way to Bogdanov, as the historical and collected experience of production.9 But unlike Bogdanov, he did not attempt to prescribe what the culture of the workers should look like. Nor would the workers be tasked with generating a new culture, as this was already happening every day. The dominated class, which carried out the production, would slowly gather more and more experience, finding better ways to organize society and knowledge. The ruling class, which had first organized society in a progressive manner, along its own rules, would slowly see the steam fade. Cracks would appear, such as the new doctrines by Marx, as the superstructure showed itself incapable of adapting to the new methods for producing knowledge. The workers would slowly move to adopt their self-produced organizational systems as their new guiding principle, as they moved to turn the world upside down once again. Once the tension became too large a revolution would take place. The old way of organizing society would be replaced by a new one, which was both a continuity and a rupture from the previous one. But Caudwell saw that despite the revolution, there was a degree of continuity in the new superstructure. He understood that if the bridge between intellectuals and workers was not built after the revolution the cycle would continue.

The similarities between these three thinkers are immense. Bogdanov, Caudwell, and Gramsci all saw that the seeds for a new method of organizing knowledge was within the workers themselves, either as a collective, through folk tales or both. Their notions of pedagogy and the role of culture finds echoes in many decolonial thinkers such as Franz Fanon, Mao Zedong, Amilcar Cabral, and Paulo Freire, who, within their differences, formulated the need for education and the development of a national or class culture as a precondition for developing a liberatory program among the colonized and dispossessed.10

Bogdanov and Caudwell knew that a radical rethinking of science and knowledge was needed, otherwise a permanent and trained bureaucracy, wielding the powers of the State for the good of the proletariat would arise. This would be the Saint-Simonian, or Comptian utopia: a dictatorship of the technocracy, where the power of knowledge would not be radically redistributed. In more than one way, he foresaw the development of the technostructure in the Actually Existing Socialist countries. We return to Revolutionary Russia below and analyze how the first Workers’ state put into practice a revolutionary education.

IV

With Marxism in power, a unique challenge would appear. The revolutionary masses required the power of knowledge to run the country, but with the sophistication of technology, this power could only be gained after a long education. The nascent Soviet Republic was faced with a difficult disjunctive: either strike a deal with the existing technostructure, the “bourgeois specialists”, despite their questionable class loyalties, or repress them and to rapidly form a new class of experts from a proletarian origin to replace the existing specialists.

At first, Lenin was particularly conciliatory towards the bourgeois specialists.11 His policies included paying extra to specialists, but this caused resentment from the workers. He was repeatedly criticized by the Workers Opposition and other left wing groups. After all, the workers who had fought the civil war remained under the same technostructure. But Lenin repeatedly noted that without machines, without discipline, it is impossible to live in modern society. It was necessary to master the highest technology or be crushed.12 Lenin’s policy of conciliation was especially prominent during the New Economic Period, where the old technocracy occupied significant positions in the planning apparatus.

Lenin never moved beyond the concept of “using” the specialists, despite the accusations of excessive conciliation. It was always a temporary evil brought about by the circumstances. And after his death, the existing specialists started to fall under the control of new “Red Directors”: workers without a significant formal education which were loyal party members. Stalin’s faction achieved greater control over the old specialists and began the process of slowly replacing them with the newly educated red specialists.

Up to 1928, there was a period of uneasy peace between workers, Red Directors and the old specialists where each faction fought for either preservation or supremacy. The first real disciplining moment for the old intelligentsia was the Shakhty affair. In 1928, fifty-three engineers and managers were arrested and put on trial for sabotage. This spectacle-cum-trial was the first instance where Stalin declared that sabotage was being used by the bourgeoisie as a method of class struggle. The full disciplining of the old Academy and the specialists would slowly follow, as Stalin would whip up class resentment against the better-paid managers.

For the Red Directors to consolidate their power over the specialists, a new generation of proletarian intelligentsia had to be educated in an accelerated manner. This debate trickled down to the admission criteria for universities. The number of places was limited, so this scarce resource somehow had to be distributed. Admissions based purely on test scores would naturally benefit those who had previous access to cultural capital and would tend to perpetuate a better-off technostructure. Class origins were made a factor depending on the year, which lowered admission requirements and at the same time forced the watering down of the curriculum. With an accelerated education, which now also required political education, narrow specialization became unavoidable. Lunacharsky, a close associate of Bogdanov, pushed for a more comprehensive and humanistic vision of education. But as Stalin’s faction came to dominate, education became focused on churning out STEM graduates. Education was “a weapon” to be wielded by the proletariat for its emancipation via the growth of productive forces. The humanistic aspect of the scientific merger was lost, and instead a more-perfect Academy was to replace the existing bourgeois one.

A second show trial in 1930, known as the Industrial Party trial, saw another group of scientists and engineers being accused of plotting a coup against the government. This was a definite watershed moment that curbed the remaining cultural capital of the old specialists. Engineers, especially those of bourgeois origin would be progressively made scapegoats for the failure to achieve unrealistic targets. This culminated in the Great Purges: a whole generation of intellectuals would be replaced by the new engineers and academicians of proletarian origin. They would be tasked with progressively more important tasks in the running of industry, and occupy the levers of power. STEM education was overemphasized to the expense of other disciplines. The ossification and rigidization of cultural studies followed suit, as the development of Marxism was considered finalized. Philosophical speculation would be reserved to Stalin himself, a philosopher-king atop the proletarian academy.

Stalin’s line became identical with the proletarian line. Nominally, class origins would determine truth. However, this was a proxy for ideological battles. The case of Lysenko, the agricultural engineer who rejected genetics in favor of acquired characteristics became emblematic of this period. Class origin became a stand-in for loyalty to the party, specifically loyalty to Stalin. Lysenko gained the upper hand not by scientific investigation, but by repression. Vavilov, the president of the Agriculture Academy was sent to die in prison, and thousands of biologists were fired from institutions. Research in genetics was completely frozen until Stalin’s death.

The proletarian technocracy grew in power, becoming more separate from the class from where it originated. In 1936, Stalin recognized the existence of a “working intelligentsia” existing alongside the peasants and the proletariat. After Stalin’s death, the Red-and-expert directors would fully flourish and run the country and military uniforms were replaced by suits. This was Bacon’s utopia, painted in red. Khruschev’s time had arrived. The old technocracy had simply been replaced by a new one, which was in many ways as elitist as the Tsarist one. Education meant specialization and a job, with which came certain privileges that were available at the end of training.

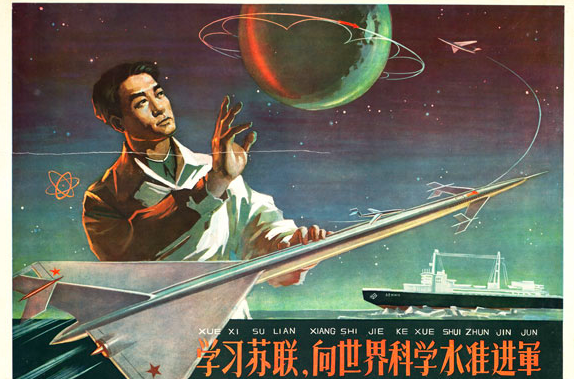

A comparable pattern took place in the cities of Maoist China. Lenin and Mao both came from a similar place: they looked West for ideas to modernize their “backward” countries and catch up. Lenin was obsessed with Taylorism and scientific management and repeatedly rallied against fideism and the orthodox church. He saw education from a perspective that did not break much with radical liberalism, where granting access to education for all was a radical reform. Mao’s political origins were in the May Fourth Movement which sought to replace China’s existing culture based on scholastic learning with something more practical. But he would progressively radicalize his program, especially after the Sino-Soviet split and his growing suspicion of the Soviet technocrats.

In 1949, the victorious People’s Liberation Army had to strike an uneasy peace with the existing intelligentsia. The capitalist development of the 20th century had created a technocracy of upper-class origin that possessed the technical knowledge required to run the country. The Chinese Communist Party was forced to be conciliatory at first as it educated its own cadres and borrowed others from the USSR. Communist China wrestled with the same Soviet problem: to generate the technocracy a new society required modernizing education. But as in the Soviet case, resources such as teachers and schools were not readily available, and the new rulers were forced to rely on the old technostructure. The scarcity of education forced tough decisions between admitting students from a lower-class background who possessed less cultural capital, or a pure “meritocracy” of test scores that benefited students from better-off backgrounds who did have access to this capital.

Up to the Cultural Revolution, education policy oscillated between radical egalitarianism and technocratic orientations depending on the faction of the Chinese Communist Party that was in the drivers’ seat. Mao relentlessly pressured to popularize education, especially as he became more and more suspicious of the new technocratically bent Soviet republic. During the Great Leap Forward, an initial attempt at reform was made. Two parallel tracks were created, the elite one designed to create the technical intelligentsia, and a popular one that would bring education to the masses. But this trend led to the replication of the old differences, now under a different guise. Many aspects of the Great Leap Forward were not very different from Stalin’s cultural revolution of the 1930s; it was mainly a top-down approach. The most infamous example is the Four Pests Campaign, a program to exterminate sparrows which ended up hurting agricultural production badly when it turned out that sparrows provided natural pest control.

Mao learned from his failures, and a second, even greater leveling experiment took place during the Cultural Revolution. In the same way as in the USSR, the desire was to produce engineers who had to be both an expert, and a red. Without going deeply into the entire history of the Cultural Revolution, more practical assignments were added to the curriculum, and class origins became an important criterion for admission. Professors were expected to merge into the masses and become part of the people, while students had to spend time in factories, or the countryside to gain practical experience and connect to the masses. Entire sections of the population became mobilized in producing and applying knowledge. Mao had learned from the failures of Lysenkoism, and scientific debate and experimentation became encouraged.13

Mao’s evolution can also be traced through his attitude towards healthcare in the countryside. At first, Mao was aware of the dire state of healthcare in the rural areas and during the Great Leap Forward a medical reform program was started where thousands of medical workers were deployed to the countryside to combat schistosomiasis. But this was not enough, as there were not enough medically-educated city dwellers for the entire countryside, and the rural countryside remained underserved. Furthermore, the doctors were not used to treating diseases common in the countryside. During the Cultural Revolution, education was provided for a new generation of “barefoot doctors” that totaled over one million. After a brief training, they would return to their villages and provide basic healthcare for the peasant commune, becoming more effective patient advocates than the medical workers of the Great Leap Forward as they were used to dealing with the diseases they were familiar with. The barefoot doctors also experimented with mixing Traditional Chinese medicine, which was less resource-draining, with Western treatments, developing indigenous treatments for diseases.

Indeed, the Cultural Revolution represents a pivotal moment in educational experiments that broke the mold. As the student-worker-soldiers set out to the countryside, new schools were built and peasants who never had the right to education saw themselves able to attend school. The movie “Breaking with old ideas” from the time is a perfect reflection of the utopia the GPCR tried to achieve: not only a class but a world of “red-and-experts”. Admission to the new universities was granted by the calluses of the hands, and the curriculum was intimately tied to the productive needs. The communist utopia would use education as a leveler. It was the culmination of the Enlightenment project, a true Science for the people.14

But these experiments would barely survive the Cultural Revolution. In the cities, the focus on generating a “Red-and-expert” technocracy would end up replicating many of the problems with the technocracy in the Soviet Union.15 Once the Cultural Revolution ebbed, the new technocracy was in a prime position to enter government. As Mao passed away and the Gang of Four were removed, Deng would use the new experts to create a technocratic China. It is hardly surprising that the Dengists were made of the same steel as the Kruschevites. Both revolutions had followed very similar paths in generating a red technocracy. And this red technocracy would be elevated to the highest position once their original patrons were gone. They would both aspire to a Red Plenty, even if the means they deployed would be different: socialist planning in alliance with the proletariat or controlled markets in alliance with a supervised bourgeoise.

V

Once revolutionaries take power, radical programs to increase literacy usually follow. To understand why it is so appealing, we can revisit an old story by Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, a historian who wrote on the ways Spaniards used knowledge to dominate the Incas. In his story, the foreman of a hacienda asked two Incas to deliver ten melons and a note to the Spanish Conquistador who was the owner of the farm. The foreman warned the Indians that the paper would reveal the destinatary the truth in case the melons were missing. The Incas ate two of them but did so far away from the paper in the hopes that the paper would not notice them. When they handed the eight melons to the Spaniard, he asked for the two missing ones. The Indians then stood in awe of the power of the written word and thought the Spaniards semi-divine.

In revolutions outside of the imperial core, literacy programs are a way for people to break down old barriers. Where the ruling class has used complicated legal frameworks to ensure its domination, literacy campaigns such as those conducted in Cuba, Nicaragua or Burkina Faso help in leveling the playing field and have an impact beyond a single generation. However, it is not enough to teach the dispossessed the tools of the ruling class. We have to stop and ask ourselves, what is being taught? These programs can be contained within radical liberalism, which is not to say that they are bad but insufficient. We have to understand that the roots of the public school in the imperial core, or the birth of the Autonomous Universities of Latin America, were the achievement of radical liberal programs. But programs like “Indian Boarding Schools” also fall into this category. Leveling the playing field is essential- but we must go further if we do not want to replace one system of distributing power for another one.

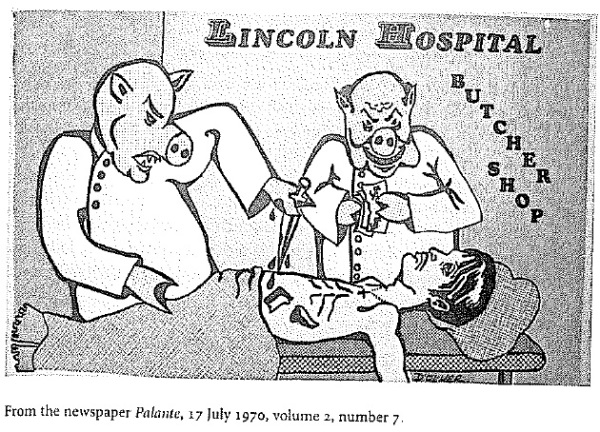

The fight against this elitist science is multifold because of the different actors taking place. Plebeians within a dominant community often fight for a science for the people, without questioning the existing cosmovision that organizes society and production. A good example of challenging the power structure of Science is the Health Program of the Black Panthers.16 In the late 1960s, the healthcare structure in the black community was in an extremely dire state. The Panthers set out to build people’s clinics, in an attempt to democratize the access to healthcare. If they had limited themselves to opening new clinics, staffed with doctors who learned “official medicine” from respectable schools, this program would remain outside of the control of the people. Nothing would have been done to empower them or to tap into their knowledge. The same way that the teachers of a public school still remain bound to a curriculum outside their control, the People’s doctors would remain bound to the authority of a “neutral” medicine.

But The Panthers went further and were able to transcend liberalism. Imitating Mao’s “barefoot doctors”, they allied with radical scientists and with other radical groups such as the Young Lords to form a real program of “Medicine for the People”. The Panthers would place community experts as equals to the medical experts and merge their knowledge to address the health problems of the community. They attempted to make explicit the racism of “official” medicine so they could break it. They conducted a massive campaign around Cystic Fibrosis, a disease that mainly affects people of African origin, which despite a high rate of incidence was never seriously researched. They denounced stories of racist abuse by medical professionals, such as the case of Henrietta Lacks, which made explicit the structural racism in medicine. The Young Lords would go as far as temporary occupying Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx to denounce the medical mistreatment of blacks and Latinxs. They were evicted by riot police but negotiated a space with the hospital where they set up a People’s Program for several years. As part of this program, the Young Lords set up a clinic for detox while providing political education. They assisted the doctors with interpreting services, building on their understanding of their communities’ problems. The Peoples’ Program would be put to a violent end by Mayor Ed Koch in 1978 after several years of success.

In the context of settler-colonialism, Marxism too often forgets that it was born of European Origins and that there are other ways of organizing the collective knowledge and experience of society. The knowledge produced by Euroamerican capitalism has been arranged towards two main motives: increasing the productivity and profit of capital, and the development of weapons to bring capitalism on a gunboat. This is reflected in an educational system that values technical and “hard” science above all, where Goldman Sachs executives question whether it is profitable to research the cure to certain diseases instead of treating the symptoms in perpetuity.

Programs for an emancipatory science must understand that they have to serve the entirety of those dispossessed, or will end up perpetuating the colonial structures that are ingrained in Science due to its dual role in society: both an episode in the growth of human knowledge in general, and a product of the Western capitalist societal organization. Education and Science can be used for assimilation as well as for empowerment.17 The dispossessed should not simply be assimilated into the existing framework because this will mean epistemicide. A radical education program must take into account not only the material conditions of the people it is seeking to liberate but must also ensure that their cosmovisions are respected. A decolonized science must challenge the entire cosmovision of the settler class.

As an example, Amerindian Traditional Ecological Knowledge is of real interest to Euroamerican science due to its utility in ecological management. But simply absorbing this knowledge as better ways to manage a farm or a forest into our system is trying to fit a piece in a different puzzle. First of all, knowledge isn’t granted for “safekeeping” and assimilation in a supposedly more advanced cosmovision. But even if we’re willing to ignore this, TEK is incommensurable to Western Science. We have to understand how deeply connected TEK is to the cosmovision of Amerindians, who value the connection to the land above all.18 While the West has striven towards speed and productivity assuming it can bend nature towards its will, Amerindians have organized their knowledge towards a homeostatic relationship with nature, recognizing that it is part of the world-system. In this context, it is not strange that one of the first rebels against the Cartesian science, Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, was a fine botanist.

One cannot simply look at TEK and think that Western Science can absorb an entire complex cosmovision as a subcompartment of a capital-oriented science labeled ecology. Denoting Indian Science as primitive, or less advanced simply ignores the ways different people have chosen to arrange their collective experience around certain priorities. Marxists must understand that there are many ways of arranging knowledge, all subordinate to the criterion of truth-through-practice, instead of granting preference to a single one.19 We must fight, as the Zapatistas say, for a world where multiple cosmovisions fit. In Settler-Colonial lands, if we do not clearly understand the dual nature of Science, we risk occupying sacred land to build a telescope without understanding why this is wrong.

VI

Galileo did not teach much to the weaponry makers of the Arsenal, he just systematized their knowledge. Since then, science has moved far, and the gunboats stand in stark contrast with the weapons of mass destruction that have been made available in the 20th century. The nuclear bomb, if anything else, stands as a monument in the emancipation of pure science. Without equations and abstractions, without decades of work in modern physics, it would not have been possible to release such destructive force.

Such potential has of course not passed unnoticed. Today, the University in the United States maintains deep ties to the defense establishment and the military industry, being a prime recipient of military Keynesianism. Military R&D accounts for nearly half of total R&D expenditures in the United States, and they were an even higher portion during the Cold War.20 The fight for permanent technological supremacy requires the power of knowledge, and the careful cultivation of a specialized technocracy that adequately leverages the division of labor.

While some scientists refuse to work with military contractors, and radical associations can agitate the scientific community to make it aware of its collaboration with destruction, the effect is meager. Indeed, most scientists are aware that they are not working for the benefit of mankind, but end up rationalizing away their job as one more cog in the brutal system of imperialism. To quote Stafford Beer at length,

“We have to find a way by which to turn science over to the people. If we can do that, the problem of elitism disappears. For surely I do not have to convince you that the man in the white laboratory coat is human after all, and would rather use his computer to serve you than to blow the world apart? Then for God’s sake (I use the phrase with care) let us create a societary system in which this kind of service is made even possible for him, before it is too late. At the moment, the scientist himself is trapped by the way in which society employs him. What proportion of our scientists are employed in death rather than life, in exploitation rather than liberation? I tell you: most of them. But that is not their free choice. It is an output of a dynamic system having a particular organization.”

In today’s academia, very few scientists can work in what they desire to work if they are to remain employed. They are instead forced into avenues decided by funding programs or private corporations. In the age of austerity, where the pressure to secure funding is growing as fast as research budgets are decreasing, military funding provides an easy solution.

At the same time, seeds for a scientist revolt are being planted in the new class of precariously employed academics. A system where the apprentices labor and produce knowledge while the masters take the credit has been around Academia for years – Tycho Brahe’s observatory was staffed with his own workers who produced the observation tables for which he became famous. But in the present, this antagonism has become extremely exacerbated as the number of doctoral degrees awarded grows without bounds, and the amount of professorships has stagnated. It appears as if Capitalist R&D is simply subcontracted to graduate students, with everyone along the line take a cut. Knowledge production is still linked to industry and hence labor, but produced in a more exploitative way, by specialist but proletarianized scientists. Funding incentives have set up a system where a few professorial “supermanagers” accumulate the little money that is going around, permanently sub-contracting an underpaid class of graduate students and post-doctoral researchers who suffer grave problems of stress, poverty wages and high incidence of mental illness.

A class wedge is arising, where a whole layer of academics can no longer pretend to stand outside society and are instead joining the fight for unionization and for maternal leave. Associations such as Free Radicals and the revitalized Science for the People are taking up the baton dropped by previous generations of radical scientists. Transcending economism, they instead propagandize for a democratized and liberatory science, actively questioning the neutrality of knowledge. The de-ideologization of science is crucial to propagating the hegemony of the bourgeois worldview. But the “traditional intellectuals” in the Gramscian sense are being proletarianized, and are throwing their lot with the forces for change. The radicalizing surplus “overqualified and underemployed” intelligentsia is a luxury compared to the problems of the nascent Soviet republic.

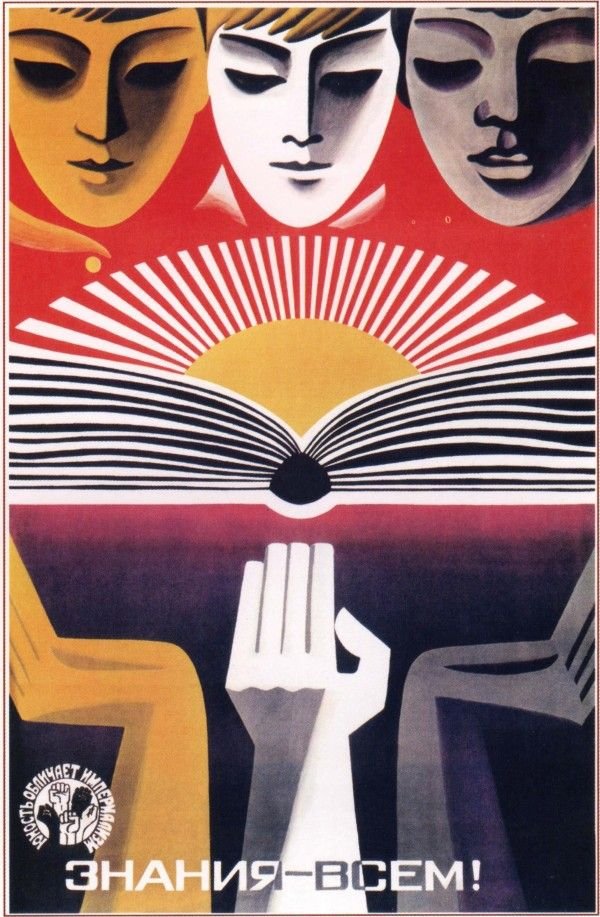

Flashpoints for the organization of a new society are appearing. The scarcity of educational resources has been considerably reduced with the advent of the internet. Resources like Khan Academy provide basic education to millions around the world despite its ideological limits. The tools for a collaborative understanding of the world and a collective organization of knowledge dreamt by Caudwell and Bogdanov already exist. Wikipedia casts a light towards what is possible in a Workers’ Republic, an emancipatory tool in-waiting. Knowledge is the living memory of our collective experience as a species won through the labor of our ancestors. It is the God humans are building. Using it as power over others is the ultimate sin.

- Clifford D. Conner (2005), “A People’s History of Science: Miners, Midwives and Low Mechanicks”

- Zilsel, Edgar. 2003. The Social Origins of Modern Science

- J. Rousseau, (1750) “Discourse on the Arts and Sciences”

- See the Stanford Encyclopedia of Science for a discussion of Comte

- A. Bodganov, (1918) “Science and the Working Class”

- For a longer exposition of Bogdanov’s thoughts, see A. Bogdanov, (1913) “The Philosophy of Living Experience”.

- This, and other episodes of Bogdanov’s life pre-revolution are recounted in D. Rowley, (1987) “Millenarian Bolshevism 1900-1920: Empiriomonism, God-Building, Proletarian Culture”.

- Longer accounts of the problems of Proletkult can be found in S. Fitzpatrick (1992) “The Cultural Front: Power and Culture in Revolutionary Russia”, S. Fitzpatrick, (2002) “The Commissariat of Enlightenment”.

- Caudwell’s philosophy can be best appreciated in his posthumous “Studies in a Dying Culture”, and “Further Studies in a Dying Culture”.

- For a discussion of the differences in treating the colonized subject between Freire and Fanon, see “Decolonization is not a Metaphor”. Mao and Cabral fall somewhere between these two thinkers.

- A longer study of these dynamics is available in K. Bailes (2008), “Technology and Society under Lenin and Stalin: Origins of the Soviet Technical Intelligentsia, 1917-41”

- See for example, V. I. Lenin, (1918) “Report on the Immediate Tasks of the Soviet Government”

- “We think that it is harmful to the growth of art and science if administrative measures are used to impose one particular style of art or school of thought and to ban another. Questions of right and wrong in the arts and science should be settled through free discussion in artistic and scientific circles and through practical work in these fields.” – On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People – Mao Zedong

- An external first-hand perspective on the democratization of science after the Cultural revolution is provided in Science for the People (1974), “China: Science walks on two legs”. Education is addressed in D. Han, (2008) “The Unknown Cultural Revolution: Life and Change in a Chinese Village”

- J. Andreas, (2009). “Rise of the Red Engineers: The Cultural Revolution and the origins of China’s New Class”

- A. Nelson, (2011). “Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the fight against Medical Discrimination”

- For an introductory perspective on education as a Western imposition, see N. Chomsky, L. Meyer, B. Maldonado (2010). “New world of indigenous resistance”. Amerindian perspectives are wide, from “Marxism, Coloniality, “Man”, & Euromodern Science“ by Roland “Ena͞emaehkiw” Keshena Robinson is a personal favorite.

- Vine Deloria (1972), “God is Red”, G. Cajete. (1999) “Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence”, and A. Waters (2003) “American Indian thought” are comprehensive introductions to the Amerindian cosmovision.

- Caudwell, and especially Bogdanov understood this when formulating their epistemology. Tektology allows for different arrangements of knowledge within

- P. Mehta, (2019) “Defense Spending: The Endless Frontier”, Jacobin