Donald Parkinson argues the seeds of what Lyndon LaRouche would become were present from the very beginnings of his organization in this analysis of the early days of his career.

The death of Lyndon LaRouche last month has prompted at least two articles in Jacobin and countless other articles in left publications about his legacy. The usual version of the story sees LaRouche as starting out as a left-winger and then finding himself going to the right out of insanity. This perspective fails to see that in fact there were continuities in LaRouche’s politics through his whole journey as a sect craftsman. At one point LaRouche, in fact, ran a whole faction in Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) that was especially popular with young Marxists who wanted to delve in the theoretical side of Marxism, preferring deep dives into Capital and the German Idealist philosophy Marx was rooted in. The truth of LaRouche is that his relevance is not just in greatly contributing to the mass popularity of conspiracy theories to the American public (which is certainly true), but that his trajectory from left to right was not without certain continuities. Rather than present a full history of LaRouche’s career and his bizarre views, this article will focus on his earlier years and how the right-wing trajectory of his career existed from the beginning.

LaRouche began as a businessman but soon found himself in the orbit of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and the Spartacist League. At this point LaRouche was just another Trotskyist as far as we know, his first signs of megalomania only coming out when he started his own group, the National Caucus of Labor Committees, or NCLC, at the 1968 Convention of SDS. SDS was in the midst of factional strife, with the Progressive Labor Party/PLP (whose politics we can be briefly described as a sort of workerist ultra-left Stalinism) aiming to take control of the organization. LaRouche, at this time going by the name Lyn Marcus, was able to win over a cadre of youth disaffected with the PLP and made a name for himself as a Marxist economist whose insider knowledge of the capitalist system meant he understood certain economic truths the rest of the left was blind to. His book Dialectical Economics can still be found in academic libraries today and is full of obscurantist philosophical tangents on German idealism while claiming to be the only modern interpretation of Marx that was correct.

It was through his grand seminars on Capital and reading groups in Greenwich Village that LaRouche would build up his following. One of his main interests was Rosa Luxemburg’s theory of crisis, which suggested that capitalism would inevitably break down once it could no longer expand into new markets. LaRouche was fascinated by this idea and saw the breakdown of capitalism on the horizon. Yet for LaRouche, the New Left were all either Stalinist racial nationalists or dopehead hippies with no political direction. The NCLC, on the other hand, was armed with a correct interpretation of the economy and a leader with his finger on the pulse of its direction. Claiming to be the only person to correctly interpret Marx’s Capital while the rest of the New Left were theoryless barbarians, LaRouche attracted many students and petty-bourgeois professionals, who were promised that their sect would be the only one able to lead the coming mass strike wave caused by an inevitable crisis.

Eventually, the NCLC was kicked out of SDS, the reason being extremely important for understanding LaRouche’s trajectory. The NCLC took the side of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), led by the conservative social-democrat Albert Shanker, in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville strike in 1969, where teachers struck against a community control program that was meant to empower the voices of black parents in the running of schools where their children faced racial discrimination. LaRouche’s backing of Shanker and what much of the New Left saw as essentially a hate strike already struck out a brand of essentially conservative workerism, with ultra-left rhetoric about workers self-emancipation being mixed with tailing the right wing of the labor movement. LaRouche was able to stake himself out in the New Left as the exception to the “race obsessed” leftists who put a strong emphasis on anti-racism and third world liberation struggles. The LaRouchites demonstrated a sort of conservative economism that would stay a central part of their ideology: concessions to chauvinism became outright propagation of chauvinism as the organization developed.

LaRouche’s rejection of community control in favor of reactionary trade unionism distinguished the org from the beginning. The LaRouchites posed themselves as the “mature” leftists in comparison to the “degenerates” who made up the New Left, dressing in suits and throwing out the Bob Dylan for Beethoven. Instead of reading Hunter S. Thompson or Allen Ginsberg, NCLC cadre prided themselves on their reading of classical German philosophy like Fichte and Leibniz. It was not unknown for Leftist organizations of students aiming to engage with workers to try and “get clean” and reject what was seen as a petty-bourgeois counterculture and taking up an identity of straight-laced respectability instead. The NCLC took this to the fullest, calling on their membership to become “world-historical.” The appeal was one of holding a deep knowledge the rest of the world was missing out on, a knowledge that would save the world from all kinds of cataclysms such as nuclear war or fascist takeover. This was not unknown among left groups, but the NCLC took it to a higher level of professionalism guided by LaRouche’s business training. While they were essentially a sect degrading into a cult, they nonetheless were able to maintain existence despite their ideas being considered a “lunatic fringe” of the left.

The LaRouchites were not just an ordinary Trotskyist sect, with the cult-like nature of the org becoming more and more intense internally. According to his biography, LaRouche was already training paramilitary wings for the NCLC in 1971.1 LaRouche proclaimed himself not just a paradigm-breaking thinker of economics, but also of psychoanalysis, developing a conspiracy that the Tavistock Institute was brainwashing Americans. This necessitated counter-brainwashing within the organization, which was really just LaRouche imposing his own brainwashing. When under criticism for brainwashing his followers, LaRouche said the following:

The nature of the actual processes of the human mind is such that brainwashing could not be effectively accomplished by private individuals or small groups within society. Only a government agency can effectively brainwash a victim.2

This was while the LaRouchites were still essentially leftist, and were also establishing cells in Europe. Here the roots of his conspiracy about the global dominance of the British monarchy can be found, with him claiming the London-based Tavistock Institute was part of a “Rockefeller-CIA” axis. LaRouche’s psychological analysis also led him into bizarre crypto-fascist theories of national character, leading him to pen tracts like The Sexual Impotency of the Puerto Rican Socialist Party. For LaRouche, as outlined in his book Beyond Psychoanalysis, every culture has its own character that got in the way of the full development of revolutionary potential. LaRouche would write in Beyond Psychoanalysis that:

In political mass organizing, the socialist propagandist and individual organizer in effect strips away. The solution to this apparent difficulty appears in the critical aspect of the persona of the worker, and so understanding of the point that all abstract (formal) momentarily implicitly reduces that worker to the ideas, to the extent they reflect or are susceptible of wretched state of a “little me.”3

Once this character is stripped away, it can be replaced with a positive and socialist one, a “stripping and rebuilding process.” In the book LaRouche describes the issue of petty-bourgeois cadre and says that their petty-bourgeois biases make this “stripping and rebuilding process” more intense in those cases, and says their inherent biases that make them “fail to see the class in-itself” display nothing less than a clinical hysteria that must be fixed through psychoanalytic therapy. LaRouche’s organization comprised mostly students and professionals, which meant that only psychoanalysis led by the party could fix the organization of petty-bourgeois alignment; this amounted to a full-on cadre program that involved attempted brainwashing. While many Marxists in the 60s and 70s took interest in Freud, LaRouche saw psychoanalysis as not just an interesting theoretical tool but a way to mold cadres to the correct politics, with the party taking on the role of a clinical psychologist.

LaRouche was equally paranoid about the Soviets, and while his roots in the Anti-Stalinist Left did give him a knowledge of the crimes of Stalinism and the USSR, LaRouche took being critical of Stalin to an absurd level, beyond the mere ‘Stalinophobia’ of some leftists (whose opposition to Stalin led them to give a blind of eye towards imperialism at times). Instead, LaRouche took it to the level of physically attacking the CPUSA in what was called Operation Mop Up, where the NCLC would behave like Stalinists at their worst. Regardless of how much LaRouche proclaimed to be against the crimes of Stalinism, his own actions went beyond any of the crimes committed by Marxists-Leninists in the US in this period.

Operation Mop Up would be another turning point for LaRouche, where most would say the organization exited the camp of the left entirely and started to become a fascist organization. Yet during Operation Mop Up, LaRouche still saw the group as a leftist organization that was fighting Stalinism and its loyal opposition, Trotskyism, who were the greatest threat to the workers’ movement because they threatened the NCLC’s “hegemony” in the left. Operation Mop Up was simply the vanguard doing the dirty work necessary; the rest of the left was all corrupt, mentally ill, and steering the masses off track. Only LaRouche and his small group of followers were smart enough to understand the truth, which was contained in the writings of the NCLC newspaper New Solidarity. Operation Mop Up was functionally fascist though, in the sense that the armed gangs of LaRouche were physically attacking Leftists and using violence to break up their organizing. This is ironic considering LaRouche’s anti-Stalinism, which condemned the Moscow show trials where political differences were solved with violence rather than discussion and democracy. A description from a 1976 report on the NCLC by the magazine Crawdaddy captures the thuggish nature of Operation Mop Up:

Incidents are too numerous to mention, but among the choicer ones were disruption of a Martin Luther King Coalition meeting in Buffalo where they beat a women who was seven months pregnant; a riot at Columbia where about 60 NCLCers stormed a stage during a mayoral debate in a failed attempt to assault the CP candidate, and an attack on an SWP meeting in Detroit where they beat a paraplegic with clubs.4

NCLC wreaked havoc on the left, but their activities actually inspired Trotskyists and Stalinists/Official Communists to unite, with the SWP, Spartacist League, and CPUSA, among other groups, forming united fronts in self-defense against the NCLC. This was an example of an anti-fascist united front at work, but against an ostensibly leftist group. Yet the NCLC was worse than a sect: it was a cult where the great leader was invested in using psychological techniques to manipulate his followers. They also held to a “color-blind” ultra-workerist vision of Marxism from the beginning, despite their largely petty-bourgeois professional composition. Yet Operation Mop Up would see the NCLC make a complete break from the left and develop its politics in a direction that can only be described as a spontaneous form of fascism emerging out of a neurotic cult leader anxious about de-industrialization.

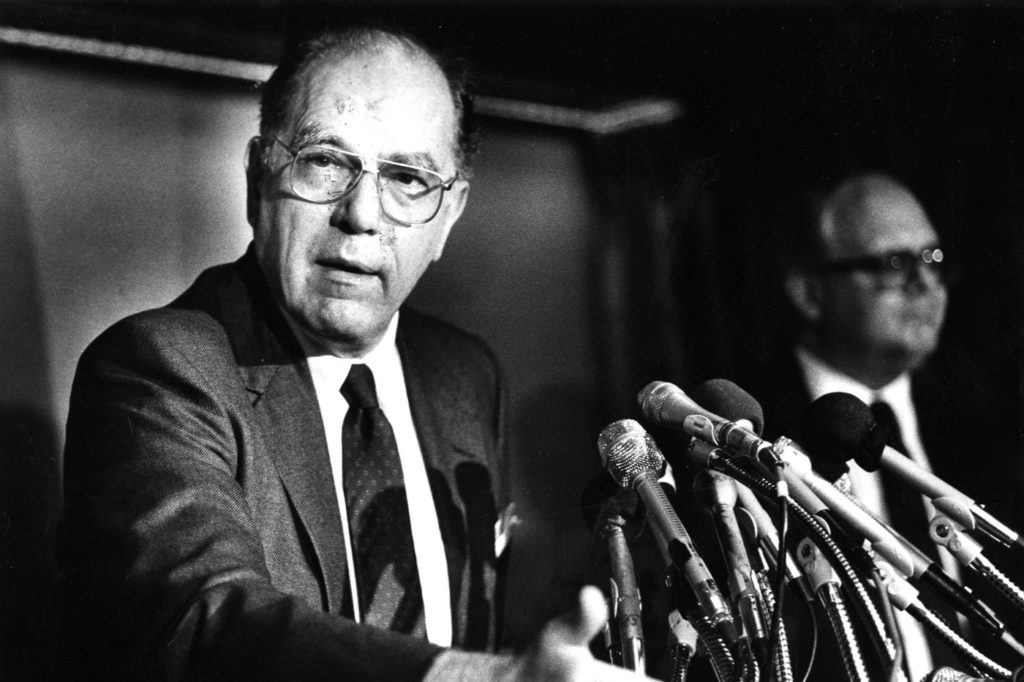

members of LaRouche’s NCLC

The NCLC changed their politics to argue for American nationalism, arguing for what they called “Hamiltonian” economics. LaRouche was witnessing the rise of financialization and de-industrialization in the core economies, which saw him change his ideology to one which promoted capitalist development of heavy infrastructure through a mixed economy. This was a worldview that saw productive capital as a positive for the economy and finance capital as unproductive, the two counterposed to each other in a “good vs. evil” way. This view of capitalism was shared by earlier fascist thinkers and would inspire LaRouche to become increasingly antisemitic. LaRouche, after his complete alienation from the left, took a producerist turn, trying to form a sort of American populism “beyond left and right” while still maintaining the inevitably of a grand breakdown crisis that would destroy America. In a 1977 interview, Costas Axio, NCLC chief of staff for New York, said of his organization:

“We are socialist, but first we must establish an industrialist capitalist republic and rid this country of the Rockefeller anti-industrial, antitechnology monetarist dictatorship of today.”

One can trace an almost logical path in his transformation from a bizarre heterodox Trotskyist to a developmentalist “Hamiltonian” producerism. The 1970s were an incredibly difficult period for the labor movement, where the capitalist class abandoned the post-war compromise that instituted a sort of Fordist stability to the workforce. This stability was being undermined by transformations in capitalism, as financialization and de-industrialization saw the size of the industrial workforce decrease and the rise of a service sector and informal economy, creating the period we live in now that is called “neoliberalism.” Either way, LaRouche witnessed what many theorists called “the death of proletariat,” and while clearly the proletariat did not die, it was undergoing a period of messy recomposition. This recomposition threw LaRouche’s whole vision of revolution out the window. LaRouche imagined that a intensifying capitalist crisis would lead to increasing quantities of mass strikes, which would eventually form workers councils out of strike committees that formed to coordinate the strikes. This strategy relied heavily on a conception that the strength of the proletariat was its ability to withdraw its labor power. Hence de-industrialization robbed the proletariat of its strength, meaning for LaRouche that the rational response was to fight for a reindustrialization of the United States. Trotksyist Tim Wohlforth’s summary of LaRouche’s views is useful here:

The second strand of LaRouche’s thought was his Theory of Reindustrialization. He began with a rather orthodox theory of capitalist crisis derived from Marx’s Capital and Luxemburg’s The accumulation of Capital. He was convinced that capitalism had ceased to grow, or to grow sufficiently to meet the needs of poor Americans. This created an economic crisis that would only worsen.

In order to overcome stagnation at home and revolution abroad, the metropolitan countries needed a new industrial revolution in the Third World. LaRouche expected this to take place in India. The advanced nations would use their unused capacity to make capital goods and export them to India, to be combined with the surplus work force to carry through this worldwide transformation. LaRouche called this the “third stage of imperialism.” Today it remains at the heart of his economic theory.5

If LaRouche was a critic of capitalism, in the end, he preferred the “good productive capitalism” of Fordism to the world of financial de-industrialization as a lesser evil. It would soon go from a lesser evil to the focus of LaRouche’s ideology. LaRouche would drop the Luxemburgism (while still using her theories of crisis to the end) and focus on his pro-industrial corporatism, members of his organization becoming “patriots” instead of “comrades.” Now American nationalism was needed to mobilize the masses for the new industrial revolution. While one can find irrationalism in the pre-Mop Up NCLC, what was essentially a turn to the right and endorsement of nationalism made conspiracy theories flourish.

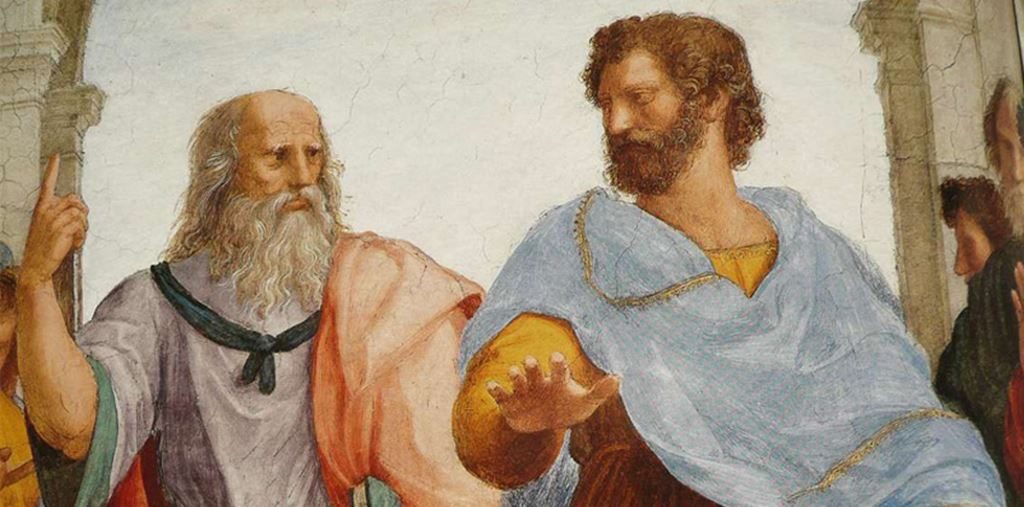

LaRouche’s conspiracy obsession can be understood through the mystified way he understood de-industrialization, financialization, and the growth of the service sector. Despite his massive knowledge of economics, LaRouche was shocked at how the 70s ended with Reagan and Thatcher instead of the apocalyptic breakdown crisis he forecasted. He could only see the changes in capitalism as the product of some irrational outside force, not the dynamics of capitalism itself. The inability of LaRouche to explain the turn of events within his own system of thoughts rationality saw him turn to irrationality, developing conspiracy theories about AIDS, Jews, the Queen of England, the Soviet Union, Puerto Ricans — the list goes on and is sure to offend any sensibly minded person. LaRouche would proclaim that “to conspire is human” while also arguing his theories were more highbrow than the “populist” conspiracy theories of the John Birch Society. LaRouche wasn’t merely a simpleminded anti-Communist peddling in fear but developed a whole worldview where history comes down to a battle between followers of Plato’s ideology and Aristotle’s ideology. Platonists value idealism and utopia, whereas followers of Aristotle were crude sensationalists and empiricists. The bourgeois and proletariat as the grand rivals of history were now replaced by classical philosophers. Through this worldview, LaRouche was able to develop a whole universe of knowledge for his followers, an “insider’s views” on what really going on. This was the attraction of LaRouche to his followers that remains to this day.

LaRouche was able to be the ultimate sect guru. He started out building a cult around those who were impressed by his particularly sharp reading of Marxism, and convinced his followers that his organization understood Marxism so well that other Marxists who were wrong needed to be dealt with violently. He then evolved beyond Marxism to develop his own ideology, yet the organization in all its transformations remained unified around the immortal knowledge and wisdom of LaRouche. One could say that his journey from Marxism began as an attempt to “Americanize” socialism, drawing from the legacy of the founding fathers and making the ultimate enemy in the world England, as if he was trying to recreate the American Revolution but for a developmentalist social-democracy. From the days of NCLC to the end of his life, LaRouche organized around the idea that only he was right and carried the correct analysis of society, and that no other leadership could save society. LaRouche was more than a personality: he carried a whole worldview with his personality that provided his followers with the one true narrative that explained history. By organizing around the view of one man’s correct theory, whether it was regarding Luxemburg’s crisis theory, Plato, or the Queen of England, LaRouche exemplified the theoretical centralism that is common in the left. By theoretical centralism we mean an organization uniting around one “correct” vision of Marxist theory or interpretation of history, rather than political centralism, or centralism around a concrete political program. Organizing around the “the truth” not only tends to lead to worshiping the “the truth” according to one person’s (or perhaps a small group of people’s) interpretation but is the recipe for developing small sects that develop authoritarian internal dynamics and ideological sterility. While most groups organized around theoretical centralism may not reach the level of the NCLC and become a fascist cult, they certainly won’t help us develop the kind of mass communist party-movement that can defeat the ruling class.

For this reason, LaRouche is in a way a warning for much the left as the sort of extreme end of what can go wrong in an organization. From the very beginning, LaRouche had a view that he held all the answers and that only an organization loyal to him would be able to solve the world’s problems. He was essentially a sectarian egomaniac. The message of LaRouche from beginning to end was that only he had the brains to see the world-historic situation of humanity and could properly lead the world to safety from catastrophe. This captures the attitude of the toxic microsect that believes that only they contain the “correct line” and therefore on this merit deserve to lead the workers’ movement. While no left group in the US has undertaken something as ludicrous as Operation Mop Up, violent altercations between left groups still happen today. The NCLC also asserted chauvinistic and color-blind workerism from the beginning, as seen in their attitudes towards the 1969 teachers’ strike. The NCLC may have been “smart” with all their knowledge of economic theory and classical philosophy, but they ultimately expressed a very politically crude economism that had an idealistic and schematic view of class struggle that didn’t follow through. LaRouche believed that crisis automatically would bring revolution, and when this wasn’t the case the group developed such a plethora of conspiracy theories that it is not possible to list them all. This reveals a level of dogmatism that sees a thinker distort reality itself in order to maintain their correctness in the face of facts. This is the kind of dogmatism we must avoid, and it is a tendency that exists in the left which must be fought against.

The NCLC is an example of the worst of where sects go, and we must recognize the internal attributes of this organization that led to its direction rather than simply see it as a the result of one individual’s psychotic break. If this leads us to see sectarian mentalities and behaviors within the existing left that resembles the early NCLC, this history should serve as a warning of where these toxic tendencies can lead if they are not averted. It is also a lesson that one must be wary of gurus and those who claim to know the answers to all our historical problems. An organization based around gurus rather than free thought and critical inquiry will always develop in intellectually bankrupt directions.