M. Earl Smith’s extensive research into and historical expose of the CIA’s activity in South America displays a historical truth which is systematically and strenuously suppressed in the American mass media. The American public consequently has a disturbingly high approval of the CIA, with more citizens supporting than opposing ‘the Company’. M. E. Smith asserts correctly that many south and central American countries have seen successful leftist governments, despite many contrary efforts of the CIA. Yet the editors of Cosmonaut believe it necessary to clarify our views on this matter: The elected governments of South America, such as the Ecuadorian government under Correa, Morales’s government in Bolivia or Chile’s social-democratic policies, all do not leave the framework of capitalism and its state order. While they certainly have improved the lives for many millions, these are gains resting on the shaky foundations (and economic vulnerabilities) of liberal capitalism.

Trying (as Allende tried) to strenuously not go beyond what is “reasonable”, implicitly, ‘reasonable’ for the ruling class and its bureaucracy, is a losing strategy in the long run. Power has yet to be seized from the hands of the bourgeoisie under these governments, and (as the example of the social-democrats Allende or even Lula shows) even political power is not immune to economic and political sabotage.

As such, the Latin American ‘Pink Tide’ movement is a different animal from Marxism altogether. Marxism’s goal is preparing the ground for successful social revolution and seeing it through. What the historical relevance of these Latin American leftist movements is to be for social revolution remains to be seen. What is sure is that those who are disturbed and outraged at the legacy and continued activity of the CIA, entombed in secrecy away from democratic control, ought to realize that the only way to mitigate the damage and suffering caused by the institution must come through the radical politics of revolution. Without an internationalist vision that calls for the abolition of the CIA as a heinous and immoral organization, along with other violent US institutions, Latin American leftists will continue being at the mercy and knife of the United States government, and American progressives and Socialists will be responsible. – Cosmonaut Editorial Board

INTRODUCTION

On 17 October 1967, National Security Advisor Walt Rostow announced in a since-declassified memo to President Lyndon B. Johnson that Che Guevara was dead. This fact in itself was not extraordinary: Guevara was executed by Bolivian forces on 9 October, and the intelligence community was abuzz with the news. What makes this memo extraordinary is the fact that, in three steps, Rostow lays out the implications of Guevara’s death. The last point bears the most significance; at this moment Rostow explains America’s policy of “preventive medicine”:

It (Guevara’s death) shows the soundness of our “preventive medicine” assistance to countries facing incipient insurgency – it was the Bolivian Second Ranger Battalion, trained by our Green Berets from June-September of this year that cornered him and got him.

The history of CIA intervention in South America is well documented, and credit must be given to scholars such as Noam Chomsky for detailing these incidents. However, what has not been explored is how these efforts have, ultimately, failed. Despite the intended long-term ramifications, most of the governments involved (after periods of military rule and instability) have returned leftist politicians to power, even if these politicians are not as purely Marxist in thought as those that came before them.

Using the case studies of Guatemala, Brazil, Bolivia, and Chile, this hypothesis plays out with a fair amount of consistency. By exploring the historical context of each revolution, the leader who was deposed, the governments that followed, and the current state of political thought in each nation, we are left with a picture that shows how, despite the best-laid plans of intervention, each country has returned to an identity that is uniquely leftist.

GUATEMALA

HISTORY

According to the CIA World Factbook, Guatemala is a small country in Central America, bordering Mexico to the north, and bearing a coastline on both the Gulf of Mexico to the north and, to the south, the Pacific Ocean. The country was originally settled around the beginning of the first millennium CE, by the ancient Mayan civilization. The country was taken over by Spain in the 1500s, spending almost three centuries under oppressive Spanish rule, before finally gaining its independence in 1821. In either what is an episode of blind irony or a tongue-in-cheek nod to their ability as the former creators of dictatorships, the CIA states the following:

During the second half of the 20th century, Guatemala experienced a variety of military and civilian governments, as well as a 36-year guerrilla war. In 1996, the government signed a peace agreement formally ending the internal conflict, which had left more than 200,000 people dead and had created, by some estimates, about 1 million refugees (CIA World Factbook).

Due in large part to the interests of United Fruit and other US-owned businesses in the country, Guatemala has a long of history of business-friendly, US-backed dictators. This includes Jorge Ubico, who was in power until 1944. On the strength of the Guatemalan Revolution, Ubico was tossed out of office in favor of Guatemala’s first democratically elected president, Juan Jose Arevalo. While Arevalo was a middle of the road president, in favor of what he termed “liberal capitalism” (a school of thought that, while still beholden to US business interests, implemented minimum wage laws, universal suffrage, and a great increase in educational funding 1, his successor, Jacobo Arbenz, sought to institute a land reform policy that seized assets from business assets and redistributed them to the workers of Guatemala. 2 This, of course, did not fall in line with the desires of US business interests in Guatemala and was counter to anti-Communist beliefs in Washington, DC.

CIA INTERVENTION

A treasure trove of declassified documents have been released by the CIA under various Freedom of Information Act requests. The documents pertaining to the CIA’s intervention in 1954 are housed online by George Washington University and have been cataloged and indexed by Kate Doyle and Peter Kornbluh. In a detailed historical analysis, Gerald K. Haines, writing for the CIA in 1995, lays out the motivating factors behind the CIA’s plans in Guatemala. With morbid detachment, Haines details how the United States formulated two plans for the assassination of Arbenz, along with plans to arm Guatemalan refugees, and how the CIA planned to use psychological warfare and intimidation tactics to achieve its ends in Guatemala. While assassination was ultimately not used to bring an end to Arbenz’s freely-elected government, Haines gives us valuable insight into the aims of the CIA when he discusses the two scenarios proposed, Operation PBFORTUNE in 1952 and Operation PBSUCCESS in 1954.3

The CIA, in a Guatemala-related document entitled A Study of Assassination, defined what assassination meant for the CIA. In their own words, assassination is:

… Used to describe the planned killing of a person who is not under the legal jurisdiction of the killer, who is not physically in the hands of the killer, who has been selected by a resistance organization for death, and whose death provides positive advantages for that organization.

One cannot help but notice the ambiguity in such a definition: the document does not exclude any type of organization from being capable of assassination, including foreign governments and business interests. In doing so, the CIA has given itself implied permission to carry out such extrajudicial killings by tailoring their own definition in a broad enough sense to allow for the pursuit of their own goals.

This document provides the CIA with its own form of justification for pursuing operations in Guatemala. The document is broken down into several sections and serves as a guidebook for any would-be American assassins. In the “Employment” section of the document, the CIA stresses that:

It should be assumed that it will never be ordered or authorized by any U.S. Headquarters, though the latter may in rare instances agree to its execution by members of an associated foreign service. This reticence is partly due to the necessity for committing communications to paper. No assassination instructions should ever be written or recorded.

The document goes on to consider the morality of such extrajudicial killings, saying that while it is never morally acceptable to kill a human being, exceptions can be made. The removal of genocidal dictators and self-defense are discussed before the CIA gives itself justification for its plans, not only in Guatemala but in every assassination plot it would carry out over the next sixty-five years. In dry, plain language, the unknown author writes: “Killing a political leader whose burgeoning career is a clear and present danger to the cause of freedom may be held necessary”.

With justification in place for its actions, the CIA moved forward with its removal of Arbenz from power. The first attempt was Operation PBFORTUNE, set in motion with the help of Nicaraguan dictator Anastaiso Somoza Garcia 4. Eventually, the US-backed dictators in Venezuela and the Dominican Republic agreed to help, and on September 9th, 1952, Operation PBFORTUNE was put into action. 5 The mission in itself was a massive failure; however, Arbenz’s government had little to do with said failure. Garcia had a penchant for discussing the coalition’s plans in Guatemala publically amongst his cabinet and government. This led the CIA to believe that Arbenz may have had prior knowledge of the attack. 6 The State Department, fearful of both an international incident and the loss of troops and supplies, aborted the mission, and the soldiers and supplies headed to Guatemala were instead rerouted to Panama. 7

The CIA, however, was not to be deterred. On March 31st, 1954, plans were put into place to assist a military junta led by colonel and director of the military academy Carlos Castillo Armas. These plans included an “extermination list” drawn up by the junta since released (without the intended individual targets) by the CIA in 1997. One of the target groups was “out and out Communist leaders whose removal from the political scene is required for the immediate and future success of the new government” (see Selection of Individuals for Disposal by Junta Group). While none of the assassinations came to fruition, Operation PBSUCCESS, as it was named, was a rounding success.

On June 18th, 1954, Armas’s forces, armed by the CIA, launched their first counterrevolutionary action in Guatemala. At first, the combined efforts were frivolous: Armas’s forces were unable to defeat governmental forces. The US intervened on the rebel’s behalf with air strikes, and nationwide civilian panic ensued. 8 A campaign of distributing anti-Communist propaganda, by means of flyer and video, was undertaken by the CIA throughout Central and South America, with great success. The government-sponsored radio system was incapacitated by upgrades around the same time, and historians are quick to give this campaign extensive credit in the success of the counterrevolutionary forces. 9 As history tells us, Arbenz’s government fell with his resignation, and the United States installed Armas as the military dictator: he ruled the country with an iron fist until he himself was assassinated in 1957. A succession of military rulers followed for the next 36 years.

AFTERMATH

Guatemala is the outlier of the four nations studied herein. Despite 36 years of military rule, the country has yet to make a move back to the leftist policies that made the revolution of 1941 so successful. The Guatemalan Civil War followed between various military juntas and leftist guerrillas, a campaign that, among other horrors, saw genocide perpetrated against the indigenous Mayan people (May). While these aggressions ended in 1996 with a peace accord on both sides that allowed for a general amnesty for all parties, the damage was done: 200,000 were dead, and the country was an economic and humanitarian disaster.

For its part, the United States has done little to alleviate any of the issues caused by its lawless intervention into Guatemalan affairs. President Clinton offered a belated apology in 1999, stating that ”For the United States, is important that I state clearly that support for military forces and intelligence units which engaged in violence and widespread repression was wrong, and the United States must not repeat that mistake”. The numbers, however, bear out how little the United States has invested in the well-being of Guatemala: for the fiscal year 2012, the United States provided less than 144 million dollars in total aid. By comparison, the United States provides 3.1 billion dollars a year in aid to Israel. The United States has a long way to go if it is to truly show contrition for its actions in Guatemala.

BRAZIL

HISTORY

According to the CIA World Factbook, Brazil existed under three centuries of colonial rule before finally gaining its independence from Portugal in 1822. It also notes that Brazil was a monarchy at its inception, and slavery was abolished in 1888. The article goes on to mention leadership prior to the rise of leftist politicians, noting that “Brazilian coffee exporters politically dominated the country until populist leader Getulio Vargas rose to power in 1930”. What the article fails to mention is that Vargas, while viewed as a populist, was a dictator who did not gain power through legitimate elections until he had ruled the country for close to two decades. While some of Vargas’s policies favored the working class, he was a staunch anti-Communist and, therefore, was seen as an asset to the United States in the years leading up to the Cold War. The CIA, much as it did with Guatemala, glosses over its involvement in the destabilization of the country on its site, stating the following about the period in question:

By far the largest and most populous country in South America, Brazil underwent more than a half century of populist and military government until 1985, when the military regime peacefully ceded power to civilian rulers (CIA World Factbook).

After several protracted parliamentary and procedural moves, leftist president Joao Goulart finally prepared to ascend to the presidency, which he did in 1963. Although Goulart was more centrist than he is usually given credit for, the United States saw his alliance with the People’s Republic of China as a harbinger of communist sympathies, and plans were made to remove Goulart from the presidency. On 31 March 1964, a military coalition led by right-wing elements of the Brazilian military moved to take over the country. They were backed, in part, by the United States and the CIA (see Kingstone).

CIA INTERVENTION

The CIA has released very little information concerning its role in the 1964 coup. As with the documentation involved in the United States’ role in Guatemala, Peter Kornbluh of George Washington University has done an outstanding job in organizing and archiving the evidence needed to show how the United States intervened in Brazil.

On 27 March 1964, a diplomatic cable arrived from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, at the State Department in Washington, DC. Composed by then-US Ambassador to Brazil Lincoln Gordon, the document describes at great length the news of an impending coup by General Castello Blanco. Gordon states almost immediately that President Goulart had aligned himself with the Brazilian Communist Party:

My considered conclusion is that Goulart is now definitely engaged on campaign to seize dictatorial power, accepting the active collaboration of the Brazilian Communist Party, and of other radical left revolutionaries to this end. If he were to succeed, it is more than likely that Brazil would come under full Communist control, even though Goulart might hope to turn against his Communist supporters on the Peronist model which I believe he personally prefers.

Gordon’s comment is curious on several levels: first, he lends credence to the theory that the Communist Party was not the only leftist element of concern to the United States. Secondly, he compares the level of control that Goulart sought to the control of the Peron family in Argentina, a dictatorship that, while borrowing from Marxist ideals, had several serious deviations from the Communist parties of the day. Finally, Gordon speaks of a campaign that he is all of certain exists, ignoring the fact that Goulart rose to power in Brazil as an elected official and, therefore, had every right to serve as the president of the country.

This document also displays how US intervention strategy had evolved since the Guatemalan Revolution in 1954. Seeing as the country was thrown into chaos, and suffered through several coups since Gordon opines that the United States should “prepare without delay against the contingency of needed overt intervention at a second stage”. This is fascinating from the perspective that the United States made the perceptive assumption that the overthrow of one leftist figure would not deter other leftist elements from rising up to fill the void left by Goulart’s absence.

On 29 March, Gordon offered an update on the impending coup in another diplomatic cable. Gordon notes the ascension of a leftist Navy Admiral to a top post in Goulart’s administration and opines that there will soon be a purging of anti-Communist elements from the Brazilian Armed Forces. Gordon appeals to the ability of the United States to promptly show force and aid the insurgency against Goulart’s government. Gordon’s communication ends with the following plea:

What we need now is a sufficiently clear indication of the United States’ government concern to reassure the large number of democrats in Brazil that we are not indifferent to a Communist revolution here, but couched in terms that cannot be openly rejected by Goulart as undue intervention.

This is similar to the strategy that the CIA and the executive branch would employ throughout its endeavors of intervention throughout the second half of the twentieth century: plausible deniability. Not only did this type of planning allow the United States to influence the outcomes of current insurgencies, it allowed it, as discussed earlier, to plan for the governments that would follow the one ousted from power.

On 3 March 1964, the coup began. Troops from several regiments began to march on Rio de Janeiro, feeling that, by taking the country’s largest city, they would hold a strategic military advantage over the government stationed in the inland capital of Brasilia. 10 The importance of Rio being a port city cannot be understated, as it provided the insurgency with a key drop point for supplies ferried in by the United States Navy. 11 When given this knowledge, President Lyndon Johnson seemed all but giddy. In a recorded conversation with Undersecretary of State George Ball, Johnson insists on actively supporting the insurgency, stating that “I think we ought to take every step that we can, be prepared to do everything that we need to do”. Johnson, however, anticipated a strong resistance despite CIA intervention, telling Ball that “we can’t just take this one”. Finally, he gives Ball a direct order to assist the coup in whatever way possible, telling him that “I’d get right on top of it and stick my neck out a little”.

The next day, April 1st, began with the United States willing to do whatever it had to, short of invasion, to ensure the deposition of Goulart. One of the few documents released by the CIA that pertains to the coup records a meeting at the White House concerning the ongoing plans for assisting the insurgency, with representatives from the State Department, the Department of Defense, Johnson’s cabinet, and the CIA. Secretaries Rusk and Gordon are pleased with the coup’s process, insomuch that they suggest that direct American intervention would be a detriment at that point (Meeting at the White House). The document moves on to other issues, including matters in Panama and Cuba, before closing with a discussion of logistics as it pertains to moving supplies to Brazil to assist with the coup. This assistance, however, would not be needed.

The next day, April 2nd, a cable arrived from the CIA. The document, striking in its brevity (just a single page long,) announces the departure of Goulart for asylum in Uruguay (see Departure of Goulart). A military government took power, and it would rule Brazil, with US backing, until elections were held in 1985.

AFTERMATH

Unlike the Guatemalan insurrection, the events in Brazil caused a far less violent fallout. Most of the benefits, however, seemed to fall into the laps of American business interests. Paul L. Williams, for example, brings to light the military government’s policy of “constructive bankruptcy,” where the state-owned industries would be starved to the point of either selling off their assets to private, foreign (mainly US) interests, or going completely broke, to the point that the government sold off their remaining pieces. 12 By the time 1971 rolled around, fourteen of Brazil’s twenty-seven major industries were owned by foreign business interests. 13

Brazilian-US relations, however, remain rocky. The United States has never offered a formal apology for its role in the removal of a democratically elected President. However, the United States has, it seems, looked for further chances to spy on and interfere in Brazilian affairs. In 2013, documents released by whistleblower Edward Snowden revealed that the National Security Administration was spying on the emails, phone calls, and texts of leftist Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff (see Borger). Despite the flagrant violation of international law, the United States still refuses to apologize (see Roberts), just as it never has for its removal of Goulart sixty-one years before.

BOLIVIA

HISTORY

The bulk of the CIA World Factbook article concerning Bolivia focuses on the current government of leftist Evo Morales, so as a source of history it leaves much to be desired. The slight section that does focus on the history of the nation, from Spanish colonial rule until the present, reads thus:

Bolivia, named after independence fighter Simon Bolivar, broke away from Spanish rule in 1825; much of its subsequent history has consisted of a series of nearly 200 coups and countercoups. Democratic civilian rule was established in 1982, but leaders have faced difficult problems of deep-seated poverty, social unrest, and illegal drug production.

Bolivia is unique in this study because, unlike the other four nations discussed, there was, until that time, no history of a successful, post-Communist Manifesto leftist government. Bolivia did have a small Communist party, but it was not until the arrival of Che Guevara that the leftist movement in the country sought to make any great strides in national politics. Guevara was not one who favored gaining power through elections: he saw the process as too contrived and slanted towards the ruling elite. Rather, Guevara was smuggled into Bolivia for one reason: to incite, much as he had in Cuba, a proletarian revolution that would lead to a single party government.

This section focuses on exploring the events surrounding CIA intervention and US foreign policy through the lens of the campaign to capture and execute Guevara. Bolivia is unique in that US troops, on the ground, trained the Bolivian Army in anti-guerrilla tactics. Also, there is conclusive proof that the CIA had operatives within the country, working both independently and within the Bolivian Army. In one small campaign, the CIA concludes that it accomplished the one act that would end Communist revolution in Latin America: the murder of a Communist icon, Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara.

CIA INTERVENTION

Guevara arrived in La Paz, Bolivia, on November 3rd, 1966. Recounting in his journal, Guevara quoted former Argentine president Juan Peron, who admired Guevara but saw his guerilla tactics as outdated, as saying that he “will not survive in Bolivia. Suspend that plan. Search for alternatives. Do not suicide”. 14

There is a trove of documents, released by the CIA between 1993 and 2013, pertaining to the CIA’s actions in containing Guevara’s insurgency in Bolivia. These, as with the documents from Guatemala and Brazil, have been archived in PDF format online by Peter Kornbluh. The documents pertaining to Guevara’s actions in Bolivia start almost two years earlier, in a CIA memo by a young intelligence analyst named Brian Latell. While most of the document focuses on Guevara’s falling out of favor with Castro in Cuba, it does spare a moment to explain Guevara’s revolutionary plans going forward. Latell states that “Che felt that his revolutionary talents now could be used better elsewhere”. 15

Bolivia was an impoverished part of South America that seemed to contain all the prime ingredients for a revolution. The United States, anticipating this (perhaps encouraged by their successes in Guatemala and Brazil, or worried by their failures in Cuba), came to an agreement with the Bolivian Army. In this Memorandum of Understanding, signed by representatives from both sides, Bolivia agrees to provide suitable training areas, individuals with talents suited to quashing revolutionary action, ammunition, maintenance of all US equipment provided for said training exercises, and provisions to the United States Army in return for training, equipment, logistical support, advice, officers, and intelligence.

Despite what appeared to be a brilliant stroke of luck, the United States had no direct knowledge of Che’s initial arrival in Bolivia. However, on 11 May 1967, Rostow offers Johnson the first credible evidence that Guevara is alive and operating in South America, not dead as previously thought. The methods, as well as the evidence itself, are heavily redacted, as are most of the documents in the Guevara collection. Rostow does point out, however, that more evidence is needed to prove that Guevara was “operational” and now merely “alive”.

Guevara’s diary offers a less than rosy view of his circumstances. An excerpt from the closest day to the White House memo above (May 13) shows the struggles that Guevara and his band of revolutionaries were having:

A day of burps, farts, vomiting and diarrhea – a real concern from our organs. We remained completely immobile trying to digest the pig. We have two cans of water. I was feeling very bad until I vomited then I felt better. At night, we ate corn fritters and roast pumpkin, plus all the leftovers from our feast the day before – those who were in a condition to eat.

The next passage, written on the same day, presents an alarming reality for the rebels:

All the radio stations are constantly covering news that some Cubans landing in Venezuela were intercepted. The Leoni government presented two of the men with their names and ranks; I do not know them, but everything suggests that something has gone wrong.

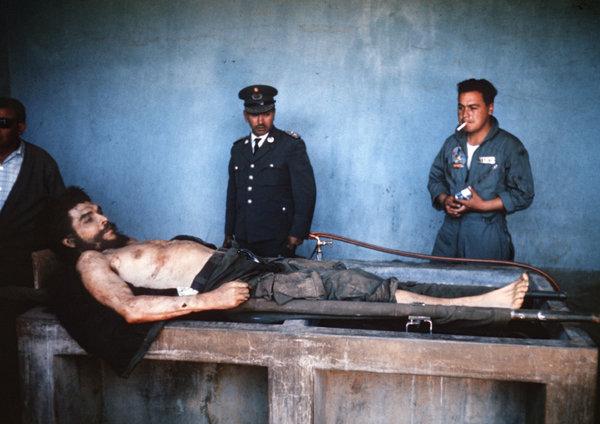

Given the struggles of Guevara and his band of confederates, it’s shocking that the Bolivian ‘revolution’ lasted as long as it did. Guevara was constantly ill, had little support from the Bolivian Communist Party, and the peasants were quick to sell him and his men out to the Army, either for extra food or under the threat of torture and arrest. Still, it came as a surprise when Guevara was captured and executed by Bolivian 2nd Battalion forces on October 8th, 1967, forces trained by the United States Army.

On 9 October 1967, Rostow offered Johnson tentative reports that Guevara was dead. At 10 AM on the same day, the Bolivian president told a group of newsmen that Guevara was dead; however, he asked them to sit on the information. In the closing paragraph, Rostow states that there are at least four revolutionaries dead, including Guevara, two fellow Cubans, and a Bolivian rebel.

Contemporary sources tell us that Guevara did pass away on the night of October 9. Guevara biographer Jon Lee Anderson describes Guevara’s last moments, stating that a sergeant named Mario Teran volunteered to kill Guevara to avenge some of his fellow soldiers that had fallen at the hands of Guevara’s band of guerrillas. Guevara, defiant even to the end, told Teran “I know you have come to kill me. Shoot, coward, you are only going to kill a man!”. 16 After nine bullets, Guevara was dead.

Three further White House documents bring a finality to the issue of Guevara’s death. On October 10, White House staffer William Bowdler expresses some doubt that Guevara is among the dead. On October 11, Rostow tells Johnson in a memo that they were “99% sure that Guevara is dead” based on currently redacted evidence. This letter also outlines the aforementioned circumstances of Guevara’s death. Finally, on October 13, Rostow provides Johnson with irrefutable proof of Guevara’s downfall. To this day, the vast majority of the document is redacted, leaving a single line of text after the censored section: “This removes any doubt that ‘Che’ Guevara is dead”.

What remained of Che’s guerrillas fled to Chile, and, on 19 October 1967, Cuban President Fidel Castro confirmed what the rest of the world knew: the greatest revolutionary of the 20th century was dead. In Guevara’s eulogy, Castro declared that the citizens of Cuba, the children of future generations, and future revolutionaries should all strive to “be like Che”.

AFTERMATH

Guevara’s death was a return to business as usual for the ruling elite of Bolivia. Dictator president Rene Barrientos, already in power as a result of a separate CIA-backed coup, ran the country until his death in a helicopter crash in 1969. Barrientos’s hand-picked successor, Alfredo Ovando, led the country until his death in 1971. Bolivia then put a socialist leader, Juan Jose Torres, in power, but he was assassinated by the CIA in 1976 as a part of Operation Condor. Several generals led the country as a part of dictatorships or as elected presidents (although the legitimacy of these elections must be questioned) until 2005, when Evo Morales was elected President, becoming the first indigenous Bolivian to run the country.

Morales is an admirer of Guevara so the influence of Guevara on Morales’s socialist policies cannot be understated. The CIA, and especially Walter Rostow, sought to erase the influence of popular revolutionaries such as Guevara from South America. However, at least in the case of Bolivia, the popular spirit of Marxist politics seems to be alive and well. Quoting Thoreau Redcrow, a doctoral candidate in International Conflict Analysis at Nova Southeastern University in Florida, “Guevara’s appeal is a result of the fact that his message is more prescient than ever in Bolivia and throughout Latin America”.

CHILE

HISTORY

Of all the articles on the CIA World Factbook website, the one covering Chile is, without a doubt, the most disgusting. The article starts out innocuously enough, describing the country thus:

Prior to the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century, the Inca ruled northern Chile while the Mapuche inhabited central and southern Chile. Although Chile declared its independence in 1810, decisive victory over the Spanish was not achieved until 1818. In the War of the Pacific (1879-83), Chile defeated Peru and Bolivia and won its present northern regions. It was not until the 1880s that the Mapuche were brought under central government control.

The article, however, takes a flagrant turn when it describes the events that led up to the installation of Augusto Pinochet as dictator in a CIA-backed coup against democratically elected Marxist president Salvador Allende:

After a series of elected governments, the three-year-old Marxist government of Salvador Allende was overthrown in 1973 by a military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet, who ruled until a freely elected president was inaugurated in 1990.

Allende was a lifelong politician in Chile, with unsuccessful presidential runs in 1952, 1958, and 1964. Allende rose to the presidency in 1970 and began an immediate process of nationalization and collectivization. The Chilean Congress, a fractured group, did not take well to Allende’s Marxist policies. There was a movement to have Allende impeached, but such efforts were protracted drawn-out affairs. On September 11th, 1973, a coup sponsored by the CIA was launched with an all-out assault on the presidential palace. Declaring that he would not surrender, Allende offered what would prove to be his own epitaph: “These are my last words, and I am certain that my sacrifice will not be in vain, I am certain that, at the very least, it will be a moral lesson that will punish felony, cowardice, and treason.”

CIA INTERVENTION

While Allende seemed intent on going down in a blaze of glory, the fact is that the CIA planned his ouster since the early days of his presidency. Peter Kornbluh once again provides us with a treasure trove of documents, all housed online by George Washington University. The first of these documents is a series of diplomatic cables from September 5-22, 1970. These cables, sent by American Ambassador Edward Korry, paint a picture that is alternatively desolate and hopeful. What is shocking about this series of cables is the candid manner in which they are written. Korry lambasts the situation, stating that “it is a sad fact that Chile has taken the path to Communism with only a little more than a third of the nation approving the choice, but it is an immutable fact.” These cables would play a significant role in Nixon’s policy as it pertained to Allende.

A handwritten note from 15 September 1970 survives, taken by CIA director Richard Helms from a meeting with President Nixon. Helms writes:

“l in 10 chance perhaps, but save Chile!; worth spending; not concerned; no involvement of embassy; $10000000 available, more if necessary; full-time job–best men we have; game plan; make the economy scream; 48 hours for plan of action”.

This meeting is detailed to a CIA operative, whose name is redacted, in a report the following day. Stating that “The President asked the agency to prevent Allende from coming to power or to unseat him,” Helms sets a deadline of September 18 for a plan. The mission is coined “Project FUBELT.”

A month passed, and several high-profile Cabinet members met to discuss further plans, plans that evolved around Chilean general Roberto Viaux; a plan entitled “Track II” was developed, with “the unfortunate repercussions, in Chile and internationally, of an unsuccessful coup […] discussed”. By this point, the United States had shown an evolution in how it involved itself with coups in South America, showing under Nixon an aggressive yet pragmatic approach. This is displayed in a document from the next day, October 16th, 1970. The document calls for Allende to be overthrown by October 24th, with the plans from “Track II” chosen. Ambassador Korry is left out of the loop (see Operating Guidance Cable on Coup Plotting). However, their plans were foiled two days later when another group working with the CIA in Chile managed to assassinate General Rene Schneider, rallying Chile around Allende. (see Cable Transmissions on Coup Plotting).

In a series of documents stretching from 3 November to 4 December 1970, the implications of Schneider’s execution and Allende’s ascension to the presidency are discussed. An “Option C” – maintaining a cool attitude towards Allende while working covertly to overthrow him – was chosen by Nixon at a National Security Council meeting on November 3 (see Option Paper on Chile). Three days later, Helms briefed the NSC on operations in Chile, omitting the CIA’s role in the first failed coup. The role of Moscow in Chile’s government is discussed and ultimately dismissed, as Helms believes that Allende “will exercise restraint in promoting closer ties with Russia”. These views are reiterated on November 9th, with the President’s plan of cool disengagement becoming official policy. (see National Security Decision Memorandum 93). Finally, CIA operative John Hugh Crimmins detailed on December 4th, 1970 the steps were taken by the CIA, in cooperation with the World Bank and other global business entities, to put economic pressure on Allende’s administration. This document calls for an effort to expel Chile from the Organization of American States.

Direct efforts to dispose of Allende, however, are not documented again until 1973. The first document from this era is from the now-defunct Defense Intelligence Agency, which offered a biographical sketch on Augusto Pinochet, the leader of a coup that had overthrown President Allende. The document is heavily redacted, yet it offers a glimpse into the background of the most brutal dictator in Chilean history (see Biographic Data on General Augusto Pinochet). On 1 October 1973, naval attaché Patrick Ryan provided the Department of Defense with a glowing review of both Pinochet and the coup that removed Allende from power. According to Ryan, “Chile’s coup de etat [sic] was close to perfect”.

By this point, the reality of Pinochet’s coup had set in. On September 12, Allende’s death was announced. Reports conflict over whether he committed suicide or was assassinated by Pinochet’s forces. In an ominous harbinger of things that were to come, Guardian reporter Richard Gott noted that:

All radio stations supporting the Allende Government have been taken over, the headquarters of the Communist Party have been raided, and the detention of 40 prominent figures in the Popular Unity Coalition, which supported Allende, has been ordered.

The next day, Gott offers a bleaker portrait of the situation when he announces that Pinochet and his junta have dissolved the Chilean Congress, having decided to rule by decree. At this point, the massacre of those who were too loyal to Allende began, and most democratic rights were suspended:

There is strict censorship of the press, and only the two newspapers owned by Chile’s most powerful industrial magnate, Agustin Edwards, have been permitted to appear. The large number of Bolivian exiles have been told to leave the country, and doubtless the contingent of Brazilians will also have to leave.

The United States, eager to complete the ouster of the socialist Allende, quickly recognized Pinochet’s government and for the next twenty plus years fostered close ties with the Chilean military dictator.

AFTERMATH

Of the four countries studied, Chile has the largest database of post-coup documents available. The George Washington website yields a whopping eight documents on the circumstances in post-coup Chile, from articles detailing the use of summary executions by the Pinochet government (see Kubisch) to documents detailing the executions of American citizens by Chilean authorities (see Popper), and on to details of the expansion of DINA, Pinochet’s dreaded “secret police” (see DINA Expands Operations and Facilities). However, the most horrifying of these documents recounts the capture and torture of Chilean leftist Jorge Isaac Fuentes. A product of Operation Condor, the intelligence garnered from this interrogation was used to push forward a culture of violent repression in Chile, including the “disappearing” of thousands of people, including Fuentes himself.

Aside from a brief aside at the UN in 1977 (UPI), the United States has never offered a formal apology for bringing Pinochet’s brutal regime to power. Close to four thousand people were murdered, another 30,000 tortured, and 1,500 simply disappeared. Another 200,000 people fled Pinochet’s regime. Today, Chile is led by a socialist president, Michelle Bachelet, who has done much to return leftist policies to Chilean politics.

CONCLUSION

Although the events of CIA intervention often led to the overthrowing of elected leftist leaders in the short term, the fact remains that most of these countries have returned to a somewhat milder strain of leftist thought. Aside from aforementioned Chile, Brazil, and Bolivia, the Democratic Republic of Congo (with President Joseph Kabila Kabange) and Nicaragua (under President Daniel Ortega) have returned leftist politicians to power in the post-CIA intervention years. This shows that, while leftist thought has been tempered, politicians inspired by socialist thought are still not only electable but preferred by the people in the countries the CIA sought to repress.

A greater failure for the CIA, however, are the countries in which the CIA did not incite fundamental change. The glaring failures are, of course, North Korea, Vietnam, and Cuba. One thing that must be pointed out, however, is that CIA actions were also responsible for reactions that led to the installation of Iran’s brutal theocracy, Iraq’s Baath government led by Saddam Hussein, and the Taliban in Afghanistan, who housed and trained Osama bin Laden, the mastermind of the 9/11 terrorists attacks. Each of these countries has been unable to recover from the aftermath of brutal regimes put into power by the CIA. The reasons behind this vary, however, the human rights abuses perpetrated by these regimes far outstrip any brutality that occurred under the preceding leftist rulers.

The influence of the desires of American business interests in the coups cannot be understated. United Fruit played a role in every regime change outlined here, and all of the regime changes led to dictatorships that were extremely friendly to American business interests. Perhaps having learned its lesson from its inaction in Cuba, the United States sought to ensure that each intervention led to the protection of the rights of American business above all else, even the native populations of said nations.

While I am of the view that the CIA, in spite of its anti-Communist tendencies, ultimately failed in its goal to protect Central and South America from anti-capitalist thought, there are those that differ in opinion. One such is the aforementioned Professor Redcrow. His view, while derisive of the CIA and full of praise for Morales in Bolivia, offers a bleaker view of the rest of the nations touched by CIA-incited insurgency:

A depressing irony is that materially, all through Latin America, much of the conditions that Guevara fought against are actually worse now than they were when he was killed. Although several governments have social democratic leaders, the structural changes necessary to overturn capitalism have not been made, nor can most governments even attempt such a measure without finding themselves the victim of a U.S.-backed coup attempt. A few hours before Guevara’s murder he was served a bowl of soup by a local school teacher and he asked her how she could possibly teach children in the dilapidated mud schoolhouse that he was being held a prisoner in. Sadly, in places like Brazil, where the wealthy take helicopters from their work to their high-rise apartments, these conditions are still present. However, what is even further away, is the chances of a guerrilla army being able to do anything about it.

While I choose to respectfully disagree with Professor Redcrow’s view of events in Central and South America, I will concede the truth that today’s leftist politics are a watered down version of what was propagated throughout Central and South America in the Cold War years. That being said, the advancement of leftist governments, including the Maduro government in Venezuela (which thumbs its nose at the United States on a daily basis) can only be seen as a positive sign for those that espouse the virtues of Marxism. As time moves forward, I only see the governments of these countries moving further to the left, despite the plans and schemes of CIA-backed American imperialism.

Works Cited

Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life. New York: Grove, 2010. Print.

“Bolivia.” CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency, 15 Dec. 2015. Web.

Borger, Julian. “Brazilian President: US Surveillance a ‘breach of International Law'” TheGuardian.com. The Guardian, 24 Sept. 2013. Web.

“Brazil.” CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency, 15 Dec. 2015. Web.

Broder, John M. “Clinton Offers His Apologies to Guatemala.” The New York Times 11 Mar. 1999. NYTimes.com. The New York Times, 11 Mar. 1999. Web.

Castro, Fidel. “Fidel Castro Delivers Eulogy on Che Guevara.” Fidel Castro Delivers Eulogy on Che Guevara. Cuba, Havana. The Death of Che Guevara: Declassified. Web.

“Chile.” CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency, 15 Dec. 2015. Web.

Cullather, Nicholas. Secret History: The CIA’s Classified Account of Its Operations in Guatemala, 1952–1954. Palo Alto: Stanford UP, 2006. Print.

Gleijeses, Piero. Shattered Hope: The Guatemalan Revolution and the United States, 1944–1954. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1991. Print.

Gott, Richard. “Allende ‘dead’ as Generals Seize Power.” The Guardian [London] 12 Sept. 1973. TheGuardian.com. The Guardian, 11 Sept. 2009. Web.

Gott, Richard. “Junta General Names Himself as New President of Chile.” The Guardian [London] 14 Sept. 1973. TheGuardian.com. The Guardian. Web.

“Guatemala.” CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency, 07 Dec. 2015. Web. 17 Dec. 2015.

Guevara, Che. Che Guevara’s Bolivian Diaries. London: Oxford UP, 1968. Print.

“Historic Photos of Dead Revolutionary ‘Che’ Guevara Resurface in Spain.” Japan Times RSS. The Japan Times, 15 Nov. 2014. Web.

“How Much Money Does the U.S. Give to Guatemala?” InsideGov.com. Web.

“How Much Money Does the U.S. Give to Israel?” InsideGov.com. Web.

Immerman, Richard H. The CIA in Guatemala: The Foreign Policy of Intervention. Austin: U of Texas, 1982. Print.

Johnson, Lyndon B., and George Ball, perfs. White House Audio Tape, President Lyndon B. Johnson Discussing the Impending Coup in Brazil with Undersecretary of State George Ball, March 31, 1964. President Lyndon B Johnson and Undersecretary of State George Bell. Rec. 31 Mar. 1964. MP3.

Kingstone, Steve. “Brazil Remembers 1964 Coup D’état.” BBC.org. The British Broadcasting Company, 1 Apr. 2004. Web.

Kornbluh, Peter. “CIA Acknowledges Ties to Pinochet’s Repression.” George Washington University, 19 Sept. 2000. Web.

May, R. A. “”Surviving All Changes Is Your Destiny”: Violence and Popular Movements in Guatemala.” Latin American Perspectives 26.2 (1999): 68-91. Print.

Moreno, Alcia. “Guatemalan Genocide.” Alcia’s Blog. Alcia Moreno, 20 Jan. 2015. Web.

“The Pinochet File: How U.S. Politicians, Banks and Corporations Aided Chilean Coup, Dictatorship.” Democracy Now! 10 Sept. 2013. Web.

Pipes, Richard. Communism: A History. New York: Modern Library, 2001. Print.

Redcrow, Thoreau. “An Interview with Professor Thoreau Redcrow.” Online interview. 08 Dec. 2015.

Roberts, Dan. “Brazilian President’s Visit to US Will Not Include Apology from Obama for Spying.” TheGuardian.com. The Guardian, 30 June 2015. Web.

Schlesinger, Stephen C., and Stephen Kinzer. Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala. Cambridge, MA: Harvard U, David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, 2005. Print.

Skidmore, Thomas E. The Politics of Military Rule in Brazil, 1964-1985. New York, NY: Oxford UP, 1988. Print.

Streeter, Stephen M. Managing the Counterrevolution: The United States and Guatemala, 1954-1961. Athens: Ohio U Center for International Studies, 2000. Print.

“Truth Commission Report.” Curitiba in English. Curitiba, 12 Dec. 2014. Web.

The United States of America. The Central Intelligence Agency. Briefing by Richard Helms for the National Security Council, Chile. By Richard Helms. 1970. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973. Web.

The United States of America. The Central Intelligence Agency. Cable Transmissions on Coup Plotting. 1970. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973. Web.

The United States of America. The Central Intelligence Agency. CIA and Guatemala Assassination Proposals, 1952-1954: CIA History Staff Analysis. By Gerald K. Haines. Washington, DC: History Staff, Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, 1995. CIA and Assassinations: The Guatemala 1954 Documents. Web.

The United States of America. The Central Intelligence Agency. The fall of Che Guevara and the Changing Face of the Cuban Revolution. By Brian Latell. The Death of Che Guevara: Declassified. Web.

The United States of America. The Central Intelligence Agency. Genesis of Project FUBELT. By Richard Helms. 1970. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973. Web.

The United States of America. The Central Intelligence Agency. Intelligence Information Cable on “Departure of Goulart from Porto Alegre for Montevideo,” April 2, 1964. 1964. Brazil Marks 40th Anniversary of Military Coup; Declassified Documents Shed Light on U.S. Role. Web.

The United States of America. The Central Intelligence Agency. Memorandum of Conversation of Meeting with Henry Kissinger, Thomas Karamessines, and Alexander Haig. By Richard Helms. 1970. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973. Web.

The United States of America. The Central Intelligence Agency. Notes on Meeting with the President on Chile. By Richard Helms. 1970. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973.

The United States of America. The Central Intelligence Agency. Operating Guidance Cable on Coup Plotting. 1970. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973. Web.

The United States of America. The Central Intelligence Agency. Secret Memorandum of Conversation on “Meeting at the White House 1 April 1964 Subject-Brazil,” April 1, 1964. 1964. Brazil Marks 40th Anniversary of Military Coup; Declassified Documents Shed Light on U.S. Role. Web.

The United States of America. The Central Intelligence Agency. Selection of Individuals for Disposal by Junta Group. 1954. CIA and Assassinations: The Guatemala 1954 Documents. Web.

The United States of America. The Central Intelligence Agency. A Study of Assassination. CIA and Assassinations: The Guatemala 1954 Documents. Web.

The United States of America. The Central Intelligence Agency. U.S. Embassy Cables on the Election of Salvador Allende and Efforts to Block His Assumption of the Presidency. By Edward Korry. 1970. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973. Web.

The United States of America. Defense Intelligence Agency. Biographic Data on General Augusto Pinochet. 1973. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973. Web.

The United States of America. Department of Defense. Directorate of National Intelligence (DINA) Expands Operations and Facilities. 1975. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973. Web.

The United States of America. Department of Defense. U.S. Milgroup, Situation Report #2. By Patrick Ryan. 1970. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973. Web.

The United States of America. Federal Bureau of Investigation. FBI Report to Chilean Military on Detainee. By Robert Scherrer. 1975. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973. Web.

The United States of America. The National Security Council. National Security Decision Memorandum 93, Policy towards Chile. 1970. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973. Web.

The United States of America. The National Security Council. Options Paper on Chile (NSSM 97). 1970. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973. Web.

The United States of America. The State Department. Chilean Executions. By Jack Kubisch. 1973. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973. Web.

The United States of America. The State Department. Kubisch-Huerta Meeting: Request for Specific Replies to Previous Questions on Horman and Teruggi Cases. By David H. Popper. 1974. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973. Web.

The United States of America. The State Department. Memorandum for Henry Kissinger on Chile. By John Hugh Crimmins. 1970. Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973. Web.

The United States of America. The State Department. State Department, Top Secret Cable from Amb. Lincoln Gordon, March 29, 1964. By Lincoln Gordon. 1964. Brazil Marks 40th Anniversary of Military Coup; Declassified Documents Shed Light on U.S. Role. Web.

The United States of America. The State Department. State Department, Top Secret Cable from Rio De Janerio, March 27, 1964. By Lincoln Gordon. 1964. Brazil Marks 40th Anniversary of Military Coup; Declassified Documents Shed Light on U.S. Role. Web.

The United States of America. The United States Army. Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Activation, Organization and Training of the 2d Battalion – Bolivian Army. 1967. The Death of Che Guevara: Declassified. Web.

The United States of America. The White House. White House Memorandum, May 11, 1967. By Walter Rostow. 1967. The Death of Che Guevara: Declassified. Web.

The United States of America. The White House. White House Memorandum, October 10, 1967. By William Bowdler. 1967. The Death of Che Guevara: Declassified. Web.

The United States of America. The White House. White House Memorandum, October 11, 1967. By Walter Rostow. 1967. The Death of Che Guevara: Declassified. Web.

The United States of America. The White House. White House Memorandum, October 13, 1967. By Walter Rostow. 1967. The Death of Che Guevara: Declassified. Web.

UPI. “US Apologizes for Role in Bloody Chilean Coup.” The Wilmington Star-News [Wilmington, NC] 9 Mar. 1977, City Final ed.: 2-A. Print.

Williams, Paul L. Operation Gladio: The Unholy Alliance between the Vatican, the CIA, and the Mafia. Amherst, NY: Prometheus, 1990. Print.