Luke Pickrell of Marxist Unity Group emphasizes the centrality of radical democracy to the communist project and reintroduces the construction of the democratic republic as the foundational political goal for socialists today. He emphatically asserts that if socialists are to defeat the tricephalic hydra of capitalist domination, we must aim for the heart – “the source and parent of all the other atrocities” – the US Constitution. Luke spoke on Marxism and Radical Republicanism at the 15th annual international convention for Platypus Affiliated Society. | Read by Aliyah VP

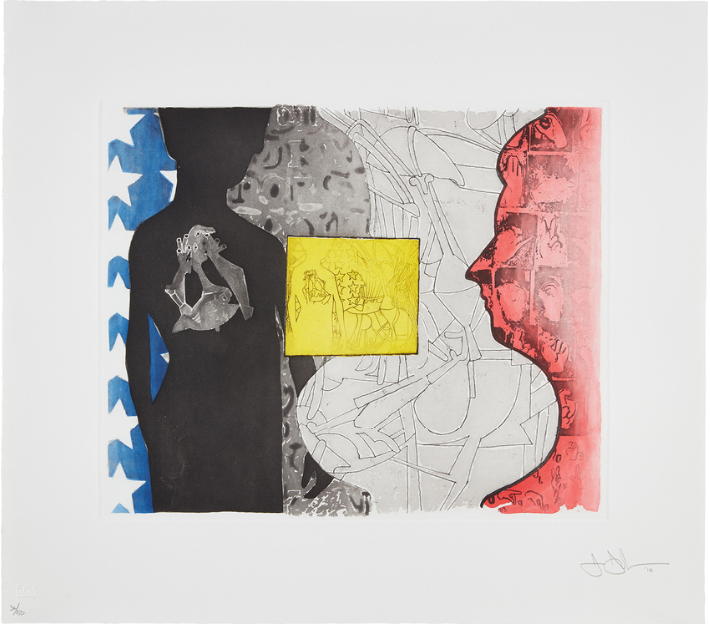

Jasper Johns, Untitled, 2010

The final point of Marxist Unity Group’s Points of Unity calls for a democratic socialist republic in North America.1 For many Marxists today, this concept is unheard of and begs many questions. In this article I will jump around a bit while remaining connected to the red thread of this demand. First, I’ll touch on why the demand for a democratic socialist republic isn’t a part of contemporary left discourse. Next, I’ll cover a bit of the history of Marx as a democratic republican and the goings-on within the 2nd International after his death. After that, I’ll focus on an influential take on Marxism and Republicanism found in William Clare Roberts’ Marx’s Inferno,2 in which Roberts presents Marx’s conception of republican freedom as focused on non-domination. Finally, I will bring us up to the present – explaining why Marx’s republicanism and the demand for a democratic socialist republic are important, and what that demand tasks the left with doing today. I’ve talked about this topic with folks from different backgrounds on the left, and they have different reactions to what I present. This is still a live question in my mind, and I am still working my mind around these ideas; in that way, this experience has been a bit like picking up a rock and watching so many small insects scatter in different directions.

History of a Demand

The demand for a democratic republic is certainly not in the vocabulary of the existing Communist, Maoist, or Trotskyist parties, nor is it a demand consistently championed by either the Democratic Socialists of America or authors published in the popular Jacobin Magazine (though a few articles about the subject have appeared). While Leon Trotsky referred to the democratic republic in his mid-1930s writings on France,3 the demand disappeared from Communist Party programs after the Russian Revolution. It remained submerged within a sea of Cold War discourse which split the world between Western ‘democracies’ on one side and various ‘dictatorships’ and ‘totalitarian’ powers on the other, with Marxism4

and the somewhat problematic ‘Leninism’5 lumped in with the latter. Both the United States and the Soviet Union had an interest in portraying their respective political system as emblematic of democracy. Lost in all of this was what Marxism actually says about democracy, democratic republicanism, and what the state form of the dictatorship of the proletariat looks like – it wasn’t the USSR.

Today, when the left speaks of democracy, it’s often in combination with the pejorative ‘bourgeois’ and scorned as such. Communism is seen as somehow better than or distinct from democracy; otherwise, democracy is seen as just a means to an end. Republicanism is similarly treated as “entirely reducible to petit bourgeois ideology that undermines the working-class struggle, [being] hence unworthy of serious study.”6 As Bruno Leipold points out, the preeminent source of Marx’s thought – the Die Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (MEGA) – refers to democratic republicans as “mere petty-bourgeois windbags.”7 In their distaste for the existing rule of undemocratic Constitutional law and order that goes by the name of democracy, socialists have thrown the baby out with the bathwater.

It’s as if everything Marx, Engels, and the Second International ever wrote about democracy, the democratic republic, and the state form of the dictatorship of the proletariat went out the window after the Russian Revolution. To a large extent, a particular reading of Lenin’s The State and Revolution8 – one that focuses on references to the soviets and largely ignores what Marx said about the Paris Commune – became the definitive statement on what the workers’ state would look like. The story goes: a true Marxist (who dreams of the workers taking state power) envisions workers’ councils, not a democratic republic; if you want a democratic republic, you want something called ‘bourgeois democracy,’ and aha! – you’ve revealed yourself as a reformist.

Another reason why much of the left rejects the idea of a democratic republic is that they misunderstand the task of the working class once it takes political power. Communism is not realized once the working class comes to power. Instead, the class struggle continues under capitalism, just at a higher level, with the working class controlling the state and therefore finally in a position to eliminate private property and commodity production. The revolution is a two-step process. Additionally, some sections of the left exemplify an economistic approach: they think only those demands which workers are already conscious of are appropriate to take up.9 If the workers aren’t currently demanding the abolition of the standing army or the abolition of the senate, then neither should socialists. Finally, there are some leftists who consciously or unconsciously remain trapped in an insurrectionary mode of thinking, which I think is best exemplified in the idea that the working class could take state power now if only it had the correct leadership. I’m relatively confident that this comes from a particular interpretation of Trotsky: capitalism is rotten and as such is ripe for socialism; therefore, the fight for democracy is a distraction from the fight for socialism.

Today, one may not know that Karl Kautsky called democracy the “light and air” of the workers’ movement,10 or that Rosa Luxemburg later exposed Kautsky as a renegade (before Lenin!) over the demand for a democratic republic in 1910. Friedrich Engels critiqued the German Social Democratic Party (SDP)’s Erfurt program for not demanding the democratic republic,11 and the 1912 program of the Socialist Party of America demanded the abolition of federal courts and the senate, the overturning of national laws only by a vote of the people, and a constitutional convention. “Such measures of relief as we may be able to force from capitalism,” declared the SPA’s program, “are but a preparation of the workers to seize the whole powers of government, in order that they may thereby lay hold of the whole system of socialized industry and thus come to their rightful inheritance.”12 In 1892, Engels reiterated: “Marx and I, for forty years, repeated ad nauseam that for us the democratic republic is the only political form in which the struggle between the working class and the capitalist class can first be universalized and then culminate in the decisive victory of the proletariat.” And what of Marx himself? His comments on the Paris Commune are the clearest evidence that he imagined working class political power taking the form of a democratic republic – and not the type of so-called “democratic republic” found in the United States and France at the time.

Only recently – due in part to a reexamination of Second International Marxism and challenges to the historiography of the official Communist parties and various Marxologists and Leninologists13 – is the centrality of democratic republicanism to Marxism reemerging. Still, the demand for a democratic republic is scarcely heard outside of a few individuals in the academy. The Communist Party USA, a century-old splinter from the SPA, advocates for democracy while leaving the U.S. Constitution intact.14 The Socialist Workers Party also defends the Constitution, claiming that it protects citizens from government abuse and enshrines rural Americans’ right to representation in the Senate15 (this last point might have something to do with the SWP’s fixation on a ‘workers and farmers alliance’). Still, any interest in reevaluating the past and challenging existing myths is a promising development. Our task is to find what lies buried under layers of history, both actual and invented. Only by drawing the correct lessons from history can we improve our work in the present.

Labor Republicans in the United States

I now turn to the history of Marx’s republicanism. Normally, I’d present this history through the lens of work by Bruno Leipold and Richard N. Hunt, who both emphasize the early 1840s and works such as the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, On the Jewish Question, and Critical Notes on the King of Prussia as examples of Marx’s development from republicanism to a republican communist synthesis. Leipold uses the phrase “radical republicans” to describe republican thinkers who pushed for democracy at the political and social level, but who Marx eventually critiqued for not consistently encroaching on the rights of private property or insisting on the political independence of the working class. Instead, I view Marx’s republicanism through the work of Alex Gourevitch and Sean Monahan, who discuss the influence of American Workers – labor republicans – on Marx and the earlier European socialists (who were very undemocratic compared to Marx).

Marx initially thought the French Revolution of 1789 had achieved something akin to human freedom by creating a democratic state.16 When Marx turned his attention toward the Americas in the 1840s, the United States was a constitutional republic with higher levels of suffrage than anywhere in Europe, and its president was a member of a political party with democracy in its name. But in reading descriptions of the United States by Alexis de Tocqueville, Thomas Hamilton, and Gustave de Beaumont, he quickly learned that political freedom doesn’t equate to social freedom.17 A state can’t be democratic, nor a people free, so long as property remains private rather than social.

Traditionally, Republicans had described freedom as the ability to control one’s labor. But by the end of the 19th century, the condition of permanent wage labor had eliminated any semblance of control over the labor process. These worker-citizens of a nominal republic critiqued their country within the republican tradition. Reviewing what he terms the “labor republican” movement, Alex Gourevitch concludes:18

The best chance republicanism had of transcending its aristocratic origins and of developing an egalitarian critique of enslavement and subjection was when someone other than society’s dominant elite used republican language to articulate the concerns. This is precisely what happened when 19th-century artisans and wage laborers appropriated the inherited concepts of independence and virtue and applied them to labor relations. The attempt to universalize the language of republican liberty, and the conceptual innovations that took place in the process, were their contributions to this political tradition.

These workers understood that the ‘freedom’ supposedly gained under the republic wasn’t living up to its potential in the face of wage labor in which the worker sold away his body and mind for the majority of the day. Wage slavery was a popular term to describe the discrepancy between the idea of freedom and the reality of unfreedom, between appearance and substance. “For he, in all countries, is a slave, who must work more for another than that other must work for him,” wrote Thomas Skidmore, founder of the Workingmen’s Party of New York; “It does not matter how this state of things is brought about; whether the sword of victory hew down the liberty of the captive, and thus compel him to labor for his conqueror, or whether the sword of want extort our consent, as it were, to a voluntary slavery, through a denial to us of the materials of nature…”19 Knights of Labor leader and First International member Terence Powderly likewise explained how wage labor made “slaves of men who proudly, but thoughtlessly, boast of their freedom—that freedom which they claim came down to us from revolutionary sires as a heritage.” Powderly wondered aloud, “…are we the free people that we imagine we are?”20 Finally, labor leader George McNeil described the American wage-laborer as someone who “assent[s]” but does not “consent,” who “submits[s]’ but does not “agree.”21

Contemporary scholars have presented various interpretations of Marx’s early republican views and later commitment to communism. Richard Hunt explains that when Marx and Engels began their collaboration in 1845, both agreed that the institutions of government and decision-making in a classless society wouldn’t be separate or estranged from the masses; there would be no division between state and civil society.22 Both young revolutionaries had a profound faith in the proletarian masses to use democracy to realize their interests, and that belief never wavered. Universal suffrage, freedom of the press, and freedom of association would lead to socialism. The trick was in getting those freedoms. Bruno Leipold contends that Marx questioned his initial republicanism after witnessing the bourgeoisie betray the revolutions of 1848 – when “the new French republic sent in the army to ruthlessly crush the insurgent workers who had naively believed that the republic would be theirs”23 – only to find a communist-republican synthesis after seeing the internal structure of the Paris Commune.24 In his interpretation of Das Kapital, William Clare Roberts calls Marx’s republican-communist synthesis a marriage between the “concern for freedom” and a “systematic dissection of capital.”25 More recently, Gil Schaeffer has traced the republican thread (though perhaps a thick rope would be a more appropriate analogy) throughout Marx’s life, writing:26

Of the three sources and component parts of Marxism, English political economy, German philosophy, and French revolutionary republicanism and socialism, Marx and Engels critique and modified all three save for the democratic republic, retaining its principles unchanged from its origin in the French Revolution as the state form of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

At no point did Marx or Engels renounce their commitment to the political rule of the working class as the first step toward winning the class struggle and realizing a classless society. At no point did Marx or Engels renounce democracy – the political expression of the majority in the interests of the majority – as how the working class would come to power. Whether or not the ruling class would push back against that expansion of democracy with violence, and whether or not that reaction would necessitate a violent revolution, was another matter. “The first, fundamental condition for the introduction of community of property is the political liberation of the proletariat through a democratic constitution,” stated Engels in 1847.27 One year later in their Manifesto the Communist Party, Marx and Engels declared that “the first step in the revolution by the working class is to raise the proletariat to the position of the ruling class, to win the battle of democracy.”28

The Second International and Republican Superstitions

The French Third Republic was declared in September 1870. Karl Kautsky detailed the numerous ways the Republic was far less democratic than the previous empire of Charles-Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte. The critique from the German Social Democratic Party (SPD)’s leading theorist was so biting that he was compelled to write a lengthy piece explaining why the SPD wasn’t secretly monarchist.29 Despite its name, Kautsky explained, the French Third Republic was just what Engels had called it years before: a monarchy with a president at its head. The modern state, to use a phrase from the pre-communist Marx of 1840, had replaced the monarch with the rule of the people only in a formal – not substantive – manner.

With the republic as its sacred banner, the bourgeoisie succeeded in winning over large sections of the French working class and some socialists like Alexandre Millerand by trumpeting the sanctity of its supposed ‘democracy’ against the alleged threat of a monarchical and clerical reaction. The bourgeoisie explained Jeffrey Isaac in a seminal work on Marx’s Republicanism, donned the “lion’s skin”30 of republican language to hide its eminently undemocratic nature. The trick was effective: “The word [republic] has a magical effect on the mind of the worker. This fata morgana fills them with hope,”31 wrote a historian of the time, quoted by Kautsky.

Even in the United States, where the struggle between worker and employer had reached a fever pitch by the end of the century, the working class eventually fell under the sway of “republican superstitions.”32 Kautsky stated: “The American worker still believes that thanks to his democracy he is better than workers living under monarchies and that he has no need for socialism, a mere product of European despotism…The main task of our American comrades…[is] to make the worker see reason…[that] just like in a monarchy, democracy has become a tool of class rule, that democracy can only again become a tool to break this class rule when he has overcome its republican superstitions.”33 The American working class forgot their predecessors’ understanding of the difference between form and content. The meaning of democratic republicanism needed rescuing from its bourgeois usurpers. That said, Kautsky’s authority on who is or is not under the sway of “republican superstitions” is contested. I think it’s a little too easy (and therefore very enticing) to point to a group of people and say that they don’t understand the undemocratic nature of the state.

Almost a decade before Kautsky’s criticism of the French Republic, Engels critiqued the SPD’s 1891 Erfurt program for its failure to demand a democratic republic and appreciate the significance of its (albeit necessary) omission from party literature. “If one thing is certain,” Engels wrote, “it is that our party and the working class can only come to power under the form of a democratic republic.”34 The Russian Social Democratic Party did what the Germans couldn’t (or wouldn’t) in putting the demand for a democratic republic in their 1903 party program,35 and Lenin polemicized against members of his party because they called themselves social democrats but weren’t championing the political movement for a democratic republic against the Tsar.36 “If you were willing to fight for political freedom,” explains Lars Lih, “you were Lenin’s ally, even if you were hostile to socialism. If you downgraded the goal of political freedom in any way, you were Lenin’s foe, even if you were a committed socialist.”37 Famously, Kautsky became Lenin’s foe after 1914. But the one-time Pope of Marxism ultimately reneged on his social democratic duty to champion the republic several years earlier during the Prussian suffrage debate in 1910.38 He thought that it was possible to bring about working class political rule without breaking from the existing state. His reneging opened him up for a forceful retort from Rosa Luxemburg, who insisted on the orthodox social democratic position that the working class can only come to power through the democratic republic. She explained that:39

By pushing forward the republican character of Social Democracy we win, above all, one more opportunity to illustrate in a palpable, popular fashion our principled opposition as a class party of the proletariat to the united camp of all bourgeois parties.

Freedom from Domination

Having reviewed some of the history of democratic republicanism in the worker and social movement during and after Marx’s time, I now present Marx’s republicanism as an interest in eliminating all forces of arbitrary domination. An extension of Marx’s republicanism was his identification of the democratic republic of the Paris Commune as the state form necessary to render the state subservient to society. Marx fought to realize freedom for humanity by eliminating all forms of arbitrary domination, the greatest source of all being the rule of capital. William Clare Roberts identifies three areas that this domination appears in capitalist society: “the political domination of the workers effected by the state, the objective domination or despotism to which workers are subjected in production, and the impersonal domination experienced by all commodity producers.”40

Marx understood communism as the struggle of the working class for self-determination and self-actualization, a struggle that would throw all of existing society into the air and free all of humanity from bonds of superstition and want. Workers strive for a voice in the decisions impacting their lives to fully engage in all the meaningful activities of life. With this desire in mind, it’s a fundamental problem for someone with an eye for non-domination that capitalist society presents a vast array of uncontrollable and arbitrary obstacles. Like the sorcerer in Fantasia who enchants a broom only to have it sweep with abandon, the working class has no control over the society it reproduces each waking hour. Marx was less concerned with stopping bad things from happening than he was with society’s ability to collectively (socially!) control its fate. The inner workings of society must be clear and comprehensible. Marx, for example, preferred direct taxation over indirect taxation because the former “prompts” the person to “control the governing powers”41 Life is tough, but it’s one thing to error or suffer because of decisions one understands and has some control over, and another to error or suffer due to arbitrary forces taking place behind one’s back.

Marx located the sources of domination in capitalist society not just in the actions of individual capitalists or politicians, but in the market as a whole – the aggregate of billions of isolated decisions. The purchase of commodities, the ability to sell one’s labor power to buy necessities, the decision to hire or fire an employee – all of these events are determined not by personal preferences or individual proclivities, but by the logic of the market operating outside of any collective debate or deliberation.42

The most obvious example of the market’s impersonal domination is the necessity of finding a buyer for one’s labor power or risk starvation. One may not want to work, but one must. William Clare Roberts provides another example of how the market overrides individual preferences: “When your favorite independent bookstore closes down in the face of competition from discount and Internet booksellers, you might moan about how good it was for your town to have such a place, and how unfortunate it is that the shop was not a profitable venture anymore. And yet you might also have done much of your own book buying on the Internet…In each of these cases, something (buying books from the local bookstore, having a unionized and local workforce, refraining from fracking) is not done, not because the agents involved don’t think it is worth doing, but because they feel compelled to bow to economic imperatives. We can set aside the question of whether or not these particular judgments about what is worth doing are correct. The bare-bones structure of the intuition is only that there may be some divergence between what is worth doing and what is economically advantageous, and that, when the two come into conflict, people might feel both compelled to follow the economic incentives, and regret forsaking their previous judgment about what is worthwhile.”43

Society is immensely unfree under capitalism because individuals cannot gather together in the service of collective decision-making and are instead at the whim of impersonal forces. Everyone – the workers who depend on the ups and downs of the market and must labor to survive; the capitalists who must squeeze surplus value out of their workforce and find the cheapest source of labor power – is dominated. Humans made this world, yet it appears as so much quicksilver in each individual’s hands. The task of communism is to take back the world we have created by giving the masses democratic control over society. The overarching obstacle standing in the way of this goal is the bureaucratic, undemocratic, alienated, bourgeois state.

Roberts writes that “so long as exchange constitutes the social nexus, producers will be dominated by market forces, workers will suffer overwork and despotism in their work, and masses will be excluded from access to the means of subsistence.”44 Yet, the market isn’t a God and the events shaping our lives aren’t supernatural.45 Marx explained:46

If the product of labor does not belong to the worker, if it confronts him as an alien power, then this can only be because it belongs to some other man than the worker. If the worker’s activity is a torment to him, to another it must give satisfaction and pleasure. Not the gods, not nature, but only man can be this alien power over man.

Human relations define capitalist society, and human relations are a matter of politics. That Marx was, in addition to everything else, a political thinker interested in political projects and political struggles can’t be overstated. He recognized domination as surmountable only through a political project injecting democracy into all spheres of human activity and thereby beginning the process of moving towards the complete elimination of private property and a new realm of human relations. It’s in the deepening of democracy – the willingness to touch private property and collectivize the means of production – where Marx takes hold of traditional republicanism as non-domination and stretches it like a rubber band.

The Democratic Republic as Political Solution

Marx was eminently aware that individuals under capitalism are unfree in the sense of being endlessly subjected to arbitrary domination. The political solution to the freedom problem appeared to Marx in the self-activity of the Parisian working class during two months in 1871: the events of the Paris Commune and the creation of a democratic republic in miniature.

During an all-too-brief two months, the Communards made crucial changes to the state: universal (male) suffrage was enacted across Paris; officials were to be revocable and accountable to their constituency; the executive and legislative branches were combined, turning the commune into a “working, not a parliamentary body”;47 the standing army was replaced with a citizens’ militia; all records of the Commune’s internal activities were publicized; the police were to be under the control of the commune and subject to recall; all judges were to be elected and likewise subject to recall; and finally: every city, village, and town would model the commune with representatives from those communes sent to make decisions in higher bodies. Decision-making would be as local as possible while retaining a degree of centralization. The state was made subordinate to society, democratic rights extended into the workplace, and the division between political and social existence was made a political project. The Communards worked under unfavorable circumstances; their revolt was isolated and lacked an organized party and clear theoretical direction. While they planned (and in some cases carried out) inroads into the arbitrary domination of the existing states, they didn’t move against the domination of the commodity market. The personal (direct) domination of the bureaucrat over the citizen and the employer over the worker was reduced, but the impersonal (indirect) domination of the market over everyone remained.

The fact that the Communards didn’t eliminate capitalism isn’t a mark against them. As I’ve already explained, the revolution is a two-stage process: political and then social. Marx described this process best when he called the Commune “…the political form at last discovered under which to work out the economic emancipation of labor”; it “supplied the Republic with the basis of really democratic institutions.”48 Kautsky stated: “only when the French state is transformed along the lines of the constitution of the First Republic and the [Paris] Commune that it can become that form of the republic, that form of government, for which the French proletariat has been working [and] fighting…”49 Lenin, in a piece written to recover orthodox Marxism, offered a provocative take on the transformative power of democracy within the democratic republic. “The [Paris] Commune … appears to have replaced the smashed state machine ‘only’ by fuller democracy: abolition of the standing army; all officials to be elected and subject to recall. But this ‘only’ signifies a gigantic replacement of certain institutions by other institutions of a fundamentally different type. This is exactly a case of ‘quantity transforming into quality’: democracy, introduced as fully and consistently as is at all conceivable, is transformed from bourgeois into proletarian democracy, from the state (a special force for the suppression of a particular class) into something which is no longer the state proper.”50 The purpose of the transitional workers’ state, understood by Lenin, is to run society and hold the bureaucrats accountable by subordinating them to the masses.51

But we shouldn’t let the grandeur of the Commune distract us from the fact that Marx was a champion of the democratic republic before 1871. His ‘Demands of the Communist Party of Germany’ – which called for a united German republic and the universal arming of the people52 – prefigured the Paris Commune by almost a quarter-century. Even earlier, Marx scrutinized supposedly democratic constitutions and made detailed lists pointing out their undemocratic provisions. Marx didn’t need the Paris Commune to make him a champion of democracy and an opponent of human bondage in all its personal and impersonal manifestations: whether iron shackles, undemocratic constitutions, or the domination of the market. The Paris Commune did provide Marx with a greater appreciation for the speed with which the workers would have to subordinate the armed forces of the state to popular control and deprofessionalize the state bureaucracy.

Tasks for Today

The socialist party embarks on its journey with the immediate goal – the democratic republic – detailed in its minimum program. The party’s final goals – communism and freedom – are detailed in the maximum program. The fight to achieve the minimum demands strengthens the working class while making inroads against existing states – such demands as: a single legislative assembly elected by proportional representation; the abolition of the independent presidency and the Supreme Court’s right of judicial review; the election of judges and other state officials; the expansion of jury trials and state-funded legal services; the unrestricted right of free speech; the abolition of copyright laws and monopolies of knowledge; the immediate dissemination of all state secrets; the abolition of police and standing army in favor of a people’s militia characterized by universal training and service, with democratic rights for its members; and the immediate convening of a constitutional convention based on universal suffrage. Fully enacted, these demands smash the existing state. The democratic republic, because it is connected to society, remains subordinate to the masses during the transition to communism. With the state subordinate, democracy would begin to penetrate all aspects of political and social life. Having obtained freedom from the domination of the rule of the capitalist state, society could work toward the freedom to self-actualize.

Many of the party’s minimum demands also appear in its internal organization. Leadership positions are decided based on one person, one vote – not by slate.53 The party minority has the right to become a majority through debate, the formation of factions, and the publication of opinions. Electeds are accountable to the membership, mandated to serve as tribunes of the people in the political arena, and recallable by a majority vote. Finances and minutes are documented and accessible. Members have the right and duty to express their ideas, especially when they conflict with those of the majority. Ultimately, the party is strong because of its “unity in diversity”54 of opinions and ideas. Debate strengthens the party by exposing all ideas to the light of day and combining the intellectual power and experience of the entire class. A strong argument can be made that, on the other hand, bureaucratic centralism renders socialist parties inoperable beyond a certain size.

Organized around democratic republican lines, the socialist party can also engage in political spaces (parliaments, Congress, etc.) that would otherwise swallow up a non-partied do-gooder. As Kautsky noted, it’s a strong party that allows for a principled engagement in politics, not the engagement in politics that makes for a strong party.55 The RSDLP lived up to this social democratic maxim by remaining in constant opposition to the Tsar (and for a democratic republic) during the Duma period of 1906 to 1917. Crucial sections of the SPD reneged on this maxim by succumbing to parliamentary cretinism, especially in prioritizing Reichstag elections over extra-parliamentary struggles for Prussian suffrage reform in 1910 and voting for war credits with the hope of winning favor after the First World War.

Finally, working within a democratically structured socialist party acclimates the masses to engage in politics, either directly as party representatives or indirectly by keeping officials accountable. This training in political life and the creation of democratic structures is necessary for the present if the future state is to be subservient to the people. The working class must learn to lead, manage, and account for all aspects of society – an eminently political project. The representatives of the party must learn to subordinate themselves to the will of the majority. Learning how to engage in disciplined and principled political bodies is one of the many ways the working class rids itself of the muck of ages. In dereliction of duty, the left all-too-frequently avoids the question of hierarchies and decision-making by dodging the issue entirely; a vague notion of “socialism from below,” or what amounts to the complete rejection of politics, is no solution to the problem of accountable leadership and leads to less democracy.56 ‘Socialism from below’ was a prevalent slogan in the International Socialist Organisation (we even made t-shirts!) The slogan expresses a desire to create distance between ‘our socialism’ as the democratic rule of the working class, and the various bureaucratic regimes that ruled in the name of socialism during the 20th century. A friend once joked that given the state of the left, he wouldn’t mind some ‘socialism from above.’ In hindsight, the fact we couldn’t imagine a state structure in which leadership is held accountable – that the only alternatives seemed to be between a mass strike (unlikely) or rule by bureaucrats (not socialism) – is telling.

Conclusion

I’ll return to the three realms of domination in capitalist society identified by Roberts: “the political domination of the workers effected by the state, the objective domination or despotism to which workers are subjected in production, and the impersonal domination experienced by all commodity producers.” Where do we strike this three-headed hydra so that it stops growing new heads? The impersonal domination experienced by all producers won’t end once the working class takes state power because capitalism will still exist. Exploring the commodity form is theoretically interesting, but it does not provide a way for socialists to engage the working class. The domination of the working class at the point of production will be a constant source of conflict – sometimes higher, sometimes lower – so long as classes exist. But focusing our attention on labor struggles to the detriment of political struggles – as some critique the Rank and File Strategy for doing – concealed the fact that the struggle of class against class is a political struggle.

Only one head remains: the political domination of the workers by the state. A massive shift takes place in the class struggle when the working class recognizes the government is a far worse enemy than their employer. At that point, the class moves one step closer to realizing its historic mission of liberating all of humanity because it moves one step closer to contesting state power. It’s to this end that Marxist Unity Group reaffirms the DSA’s statement that the USA is “no democracy at all.” We emphasize that “in preparation for the Third American Revolution, to be a socialist in this country is to be an enemy of the US Constitution.”

I’m not convinced, like I used to be, that simply saying the word “socialism” or responding to each grievance with “the problem is capitalism” is always the best approach, nor is it inherently the most “radical” thing to do. The root problem is capitalism, but starting at the root doesn’t necessarily make pulling out the tree any easier (nor is it even possible to start at the root: you must dig). Demanding a democratic republic in the United States is very radical. Challenging the Constitution is semi-sacrilegious. I asked a friend why he thinks leftists are quicker to say ‘socialism’ than they are ‘democracy’ or ‘democratic republic.’ He responded that democracy is harder than socialism – it asks more of people, demands more engagement, and a greater understanding of how our incredibly convoluted political system functions (or doesn’t function). Democracy is also hard in the sense that it challenges socialists to win the masses of people to our ideas. There are no shortcuts to lasting power. If our ideas are correct, then we should not be afraid to expose them to the scrutiny of others. Socialists believe their arguments about the necessity of socializing the economy and abolishing the commodity form will have majority support. Only at this point can we start taking the first steps toward communism.

- Marxist Unity Group. ‘Points of Unity and Immediate Tasks.’ https://www.marxistunity.com/

- Robert, William Clare. Marx’s Inferno: The Political Theory of Capital. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Leon Trotsky. ‘A program of action for France.’ https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1934/06/paf.htm

-

Richard Hunt’s ‘The Political ideas of Marx and Engels: Totalitarianism and Social Democracy, 1818-1850’ (1974) goes a long way in dispelling the mythical connection between Marxism and totalitarianism. August Nimtz’s ‘Marx and Engels: Their Contribution to the Democratic Breakthrough’ (2000) correctly describes Marx and Engels as political leaders in the mass democratic workers’ movements of their time.

- Neil Harding’s ‘Lenin’s Political Thought’ (1977) and various works by Hal Draper like ‘The Myth of ‘Lenin’s Concept of the Party’’(1990), led the way in dispelling the myth of Lenin as an aspiring totalitarian who paved the way for Stalin.

- Leipold, Bruno. “Citizen Marx: The Relationship Between Karl Marx and Republicanism.” Ph.D. diss. St. Cross College, 2017. p. 20

- Ibid. p. 20 fn. 94

- V.I. Lenin. State and Revolution (1917). https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/staterev/

- Harding, Neil. Lenin’s Revolutionary Thought: Volume One. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Press, 2019. See chapter 6.

- Kautsky, Karl. The Social Revolution. Chicago, IL: Charles Kerr & Co., 1903. p. 90

- Friedrich Engels. A Critique of the Draft Social-Democratic Program of 1891. p. 6. https://marxists.architexturez.net/archive/marx/works/1891/06/29.htm

- Socialist Party of America. “Socialist Party Platform of 1912.” https://sageamericanhistory.net/progressive/docs/SocialistPlat1912.htm.

- See, for example, Lewis, Ben. Karl Kautsky on Democracy and Republicanism. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2020; Lih, Lars. Lenin Rediscovered: What is to be Done? In Context. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2008.

- Luke Pickrell and Myra Janis. ‘Socialism with American Characteristics.’ https://cosmonautmag.com/2023/03/socialism-with-american-characteristics/

- Author’s conversation with members of the SWP in Chicago.

- Monahan, Sean F (2021). The American Workingmen’s Parties, Universal Suffrage, and Marx’s Democratic Communism. Modern Intellectual History 18 (2): 379-402. p. 387

- Ibid.

- Gourevitch, Alex (2011). Labor and Republican Liberty. Constellations 18 (3):431-454. p. 441

- Quoted in Alex Gourevitch’s ‘Wage-slavery and Republican Liberty’ (2013). https://jacobin.com/2013/02/wage-slavery-and-republican-liberty/

- Gourevitch, Alex (2011). p. 438

- Quoted in Alex Gourevitch’s ‘Wage-slavery and Republican Liberty’ (2013). https://jacobin.com/2013/02/wage-slavery-and-republican-liberty/

- Hunt, Richard N. (1974). See chapter 4 on the political development of Engels.

- Leipold, Bruno (2017) p. 8

- Ibid. p. 11

- William Clare Roberts. ‘The Value of Capital.’ p. 5. https://jacobin.com/2017/03/marxs-inferno-capital-david-harvey-response

- Gil Shaeffer. ‘On the Democratic Republic, Working-Class Rule, Dictatorship, and Reconstruction.’ p. 15 https://cosmonautmag.com/2022/07/on-on-the-democratic-republic-working-class-rule-dictatorship-and-reconstruction/

- Friedrich Engels. ‘Draft of a Communist Confession of Faith.’ p. 5 https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/06/09.htm

- Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ‘Manifesto of the Communist Party.’ p. 26. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Manifesto.pdf

- Lewis, Ben. Karl Kautsky on Democracy and Republicanism. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2020.

- Isaac, J. C. (1990). The Lion’s Skin of Politics: Marx on Republicanism. Polity, 22(3), 461–488. P. 472

- Lewis, Ben (2020). P. 251

- Ibid. p. 163.

- Ibid.

- Friedrich Engels. ‘A Critique of the Draft Social Democratic Program of 1891.’ https://marxists.architexturez.net/archive/marx/works/1891/06/29.htm

- Program of the Russian Social Democratic Party, 1903. https://www.marxists.org/history/international/social-democracy/rsdlp/1903/program.htm

- V.I. Lenin. What is to be Done? https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/

- Lih, Lars. 2008. P. 9

- On the party debate regarding the Prussian suffrage campaign of 1910, see chapter seven of Carl Schorske’s ‘German Social Democracy, 1905-1917.’ https://platypus1917.org/wp-content/uploads/German-Social-Democracy-1905%E2%80%931917-The-Development-of-the-Great-Schism-by-Carl-E.-Schorske.pdf

- Rosa Luxemburg. ‘Theory and Practice.’ https://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1910/theory-practice/index.htm

- Roberts, William Clare (2016). p. 245

- Ibid. p. 249 imposing the tax.

- Ibid. p. 85

- Ibid. fn. 118

- Ibid. p. 97

- William Clare Roberts, interview with Donald Parkinson, Cosmopod, podcast audio, February 15, 2021, https://cosmopod.libsyn.com/republicanism-and-freedom-in-marx-with-william-clare-roberts

- Karl Marx. ‘Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts: Estranged Labor.’ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Economic-Philosophic-Manuscripts-1844.pdf

- Karl Marx. ‘The Civil War in France.’ p. 4. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1871/civil-war-france/index.htm

- Karl Marx. ‘The Civil War in France.’ p. 15 https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1871/civil-war-france/index.htm

- Lewis, Ben. (2020). p. 269

- V.I. Lenin. ‘The State and Revolution.’ p. 15 https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/staterev/

- Mike Macnair. ‘Control the Bureaucrats.’ https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/552/control-the-bureaucrats/

- Karl Marx. ‘Demands of the Communist Party of Germany.’ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/03/24.htm

- Brian O Cathail. ‘The Origins of the Slate System.’ https://rupture.ie/articles/the-origins-of-the-slate-system

- Mike Macnair (2006). p. 91

- Lewis, Ben (2020). p. 133

- Mike Macnair. ‘Socialism from below: a delusion.’ https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1071/socialism-from-below-a-delusion/