Louis August Blanqui was a key revolutionary leader in the French Socialist movement. Yet when the Paris Commune erupted in 1871, Blanqui was in prison, leaving his core of followers without leadership. Failing to defeat inevitable counter-revolution, this experiment in social emancipation was crushed in blood. How would have Blanqui’s leadership affected the outcome of the Commune? Doug Enaa Greene, author of ‘Communist Insurgent: Blanqui’s Politics of Revolution’ weighs in.

Rosa Luxemburg, reflecting on the lessons of the defeated 1919 Spartacist Uprising, wrote in one of her last articles:

The whole path of socialism, as far as revolutionary struggles are concerned, is paved with sheer defeats. And yet, this same history leads step by step, irresistibly, to the ultimate victory! Where would we be today without those “defeats” from which we have drawn historical experience, knowledge, power, idealism! Today, where we stand directly before the final battle of the proletarian class struggle, we are standing precisely on those defeats, not a one of which we could do without, and each of which is a part of our strength and clarity of purpose.1

While penning those words, Luxemburg must have pondered the fate of the Paris Commune of 1871, history’s first socialist revolution. The failure of the Commune has haunted generations of revolutionary, who have wondered what it could have done differently to survive. Karl Marx believed that any uprising in Paris would fail, but when the Commune was proclaimed, he hailed them for “storming the heavens.” Yet the Commune did not last – it was isolated from the rest of France, hampered by its own indecisive leadership, and crushed by the overwhelming power of the counterrevolution. Due to the proletariat’s immaturity and inexperience, the Commune was premature and its defeat was unavoidable. However, the sacrifices of the Commune were not in vain, the Bolsheviks learned important lessons from its failure and were able to successfully take and hold power.2 Yet was the Commune destined to be just another ‘glorious defeat’ in the annals of revolutionary history, or was victory actually possible?

In order for the Commune to prevail, any strategy would have to overcome two problems. First: the weaknesses of the National Guard – the main military force of the Commune – who not only never became an effective military force, but missed their best chance in the revolution’s opening days to take the offensive against the weakened counterrevolutionaries at Versailles. Secondly: there was no clear and decisive leadership in the Commune. One figure who could have overcome both these weaknesses to provide the needed military and political leadership for the Commune was Louis-Auguste Blanqui. Blanqui was the most legendary and uncompromising revolutionary in nineteenth-century France. Blanqui believed that a revolution needed to take the offensive to be victorious. He also possessed the prestige and moral authority capable of rallying both the National Guard and the Commune to his leadership. At best, a victory for the Commune would only be a military triumph. Since Blanqui neither appreciated nor understood the socialist potential of the Commune, its final shape would likely resemble the Jacobin dictatorship of 1793.

The Significance of the Paris Commune

Lasting only 72 days, the Paris Commune was a courageous effort by the oppressed to overturn social, economic and political inequality. In its place, the Commune created new institutions of collective power which broke the existing repressive and bureaucratic state apparatus in favor of a state based on universal suffrage, instant recall of delegates, modest pay for elected officials, and the fusion of legislative and executive functions. It replaced the standing army with the people in arms. The Commune attacked the militarism of French society, putting its faith in the unity of all peoples and internationalism. The Commune fulfilled a number of promises during its short existence: it separated church and state, nationalized church property, instituted free, compulsory, democratic and secular education, made strides toward gender equality, and encouraged the formation of cooperatives in abandoned workshops. The revolutionary principles embodied in the Paris Commune continue to inspire revolutionaries across the world.3

The National Guard and the Seizure of Power

The main military force of the Paris Commune was the National Guard with 340,000 members in March 1871 – nearly the entire able-bodied male population of Paris. The National Guard possessed a long and proud history – its origins lay in 1789 Revolution when it was created by Lafayette as a citizen-militia. According to Robespierre, the National Guard defended the “citadel of the Revolution and the pure and upright citizens who conduct the revolutionary chariot.”4 During the Restoration (1815-1830) and the July Monarchy (1830-1848), the National Guard lost its revolutionary character. When the Second Republic (1848-1851) was proclaimed in 1848, the National Guard was rebuilt with a bourgeois leadership and was used during the June Days to suppress the Parisian proletariat. Under the Second Empire (1851-1870), Napoleon III again allowed the Guard to languish.

However, the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 meant that the National Guard was revived. In August 1871, as the Prussians advanced, the government enrolled most of the Parisian male population into the Guard. As the war turned against France, the National Guard became more and more indispensable to the defense of the capital. Following the devastating French defeat at Sedan in September and the capture of Emperor Napoleon III, a Third Republic was proclaimed. The Republic proceeded to expand the size of the National Guard to 90,000 and now with most of the French Army captured, they were the only organized force capable of defending the besieged capital.

Yet the Republic was frightened of this democratic armed force based among the workers. The National Guard was different than normal armies with their elitist and hierarchical ethos. All officers of the National Guard were elected (except for the government-appointed commander-in-chief) and subject to recall (allowing the battalions to reflect the ever-changing popular mood). Although revolutionary influence was limited in the National Guard, workers were already growing suspicious and hostile to the government due to its greater fear of the armed workers than of the Prussians.

Government hostility was compounded by the desperate siege conditions in Paris. The Prussian blockade had cut off food supplies, completely ruined the economy, brought wide-scale unemployment for most of the middle class. Furthermore, the government did little to organize relief efforts since they were hampered by their belief in the principles of economic freedom and, according to Robert Tombs, they were “reluctant to cause public alarm or provoke the disappearances of food stocks underground into a black market. So it introduced a bare minimum of requisition and rationing. Government policy was incoherent and less than efficient. Requisitions and controls brought in piecemeal, often too late.”5 The burden of shortages, price rises, and long queues fell heaviest on working-class families (particularly women).6 During the siege, speculators amassed enormous profits, which only made the populace more receptive to revolutionary demands for price controls and social justice.

Throughout the winter of 1870-1 conditions in Paris deteriorated even further as temperatures dropped to subzero levels. During Christmas, while people in working-class neighborhoods were dying of starvation, the wealthy districts and restaurants held festive celebrations with plenty of food. The Germans made sure Paris was reminded of war by periodical bombardment. By the time the Prussians lifted the siege in March, it was estimated that there were 64,154 deaths. According to Donny Gluckstein: “Workers suffered disproportionately, their death rate being twice that of the upper class.”7 The Republic maintained the National Guard out of necessity, and despite the low pay for Guardsmen, employment in the Guard for families could mean the difference between food on the table or starvation. As the siege progressed, more than 900,000 people became dependent in one form or another on the National Guard.

In January, the Republic concluded an armistice, which not only cost the country a large indemnity (to be paid on the backs of the workers), but surrendered the provinces of Alsace-Lorraine to the Germans. In February, elections to the National Assembly returned a monarchist majority who proceeded to approve the Armistice terms by a vote of 546 to 107. The National Assembly also appointed Adolphe Thiers as the President of the Third Republic. Thiers had a long career serving every French government since the 1830s. Under the Orleanist dynasty, he was Minister of the Interior (and later premier) where he had ruthlessly crushed the Parisian uprising of 1834. He had helped bring down the Second Republic by assisting Louis Bonaparte to attain the throne and became a deputy under during the Second Empire. Although Thiers was an early advocate of war against Prussia, he spoke out against the war when it was already lost. Through careful political maneuvering, Thiers distanced himself from the Government of National Defense when the armistice was signed. Despite Thiers’ service to so many different French governments, he appealed to almost every political faction. Thiers would be responsible for orchestrating the repression and the bloodletting of the Paris Commune.

Paris was outraged by this armistice and the elections. They had suffered heavily in the war, only to see the Republic prostrate itself before the invaders instead of rallying the people in arms to fight. The elections also raised the specter of a royalist restoration feared by Red and Republican Paris.

In a further blow to national pride, the National Assembly permitted the Germans to parade 30,000 troops through the capital on March 1. The National Guard called for continued resistance to the Germans and reorganized themselves by electing a Central Committee. Massive patriotic demonstrations were held on February 24 to mark the anniversary of the 1848 revolution. Parisians seized arms and ammunition to prepare for a final battle with the Germans. However, the First International, Vigilance Committees and other popular groups in Paris warned the National Guard against provoking a confrontation with the Prussians. Eventually, the Central Committee relented and the popular organizations decided to passively boycott the Germans. Communard participant and historian Pierre-Olivier Lissagaray offers this colorful description of how Germans were greeted when they entered Paris:

they were assailed only by the gibes of guttersnipes. The statues on the Place de la Concorde were veiled in black. Not a shop or cafe was open. No one spoke to them. A silent, mournful crowd glowered at them as if they had been a pest of vermin. A few barbarian officers were permitted a hasty visit to the Louvre. They were isolated as if they had been lepers. When they glumly retired, on March 3, a great bonfire was kindled at the Arc de Triomphe to purify the soil fouled by the invader’s tread. A few prostitutes who had consorted with Prussian officers were beaten, and a cafe which had opened its doors was wrecked. The Central Committee had united all Paris in a great moral victory; even more, it had united it against the government which had inflicted this humiliation.8

Before France signed the treaty, the National Guard and the revolutionaries in Paris were caught in a bind over how to back the war effort without also supporting the government. After the peace treaty was an accomplished fact, that problem was gone and nothing remained to distract the Parisians from confronting the government.

The National Assembly passed two provocative and vindictive decrees that brought antagonisms in Paris to the boiling point. First, the National Assembly moved to Versailles, fearing the insurrectionary mood in Paris. To all Parisians, this was a blow to the prestige of the capital. Secondly, during the war there had been a moratorium on debt repayment, which the National Assembly lifted on March 13. This struck hard both the impoverished working class and small shopkeepers. Lissagaray describes the impact: “Two or three hundred thousand workmen, shopkeepers, model makers, small manufacturers working in their own lodgings, who had spent their little stock of money and could not yet earn any more, all business being at a standstill, were thus thrown upon the tender mercies of the landlord, of hunger and bankruptcy.”9 Now the broad masses of Paris were united against the government in Versailles.

Disorder continued to rise in Paris, frightening the bourgeoisie and causing approximately 100,000 of them to leave before the revolution. The National Guard was no longer under government control, their newly appointed commander-in-chief viewed as a royalist and a defeatist.10 Versailles saw the National Guard was now a threat to their authority, property and social order. The National Assembly wanted to preserve order in the capital, but only had 12,000 regular soldiers under their command. Thiers wanted the Guard disarmed, but had to move carefully to avoid provoking an armed confrontation.

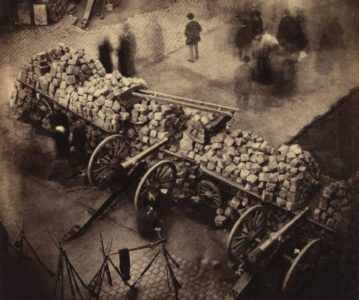

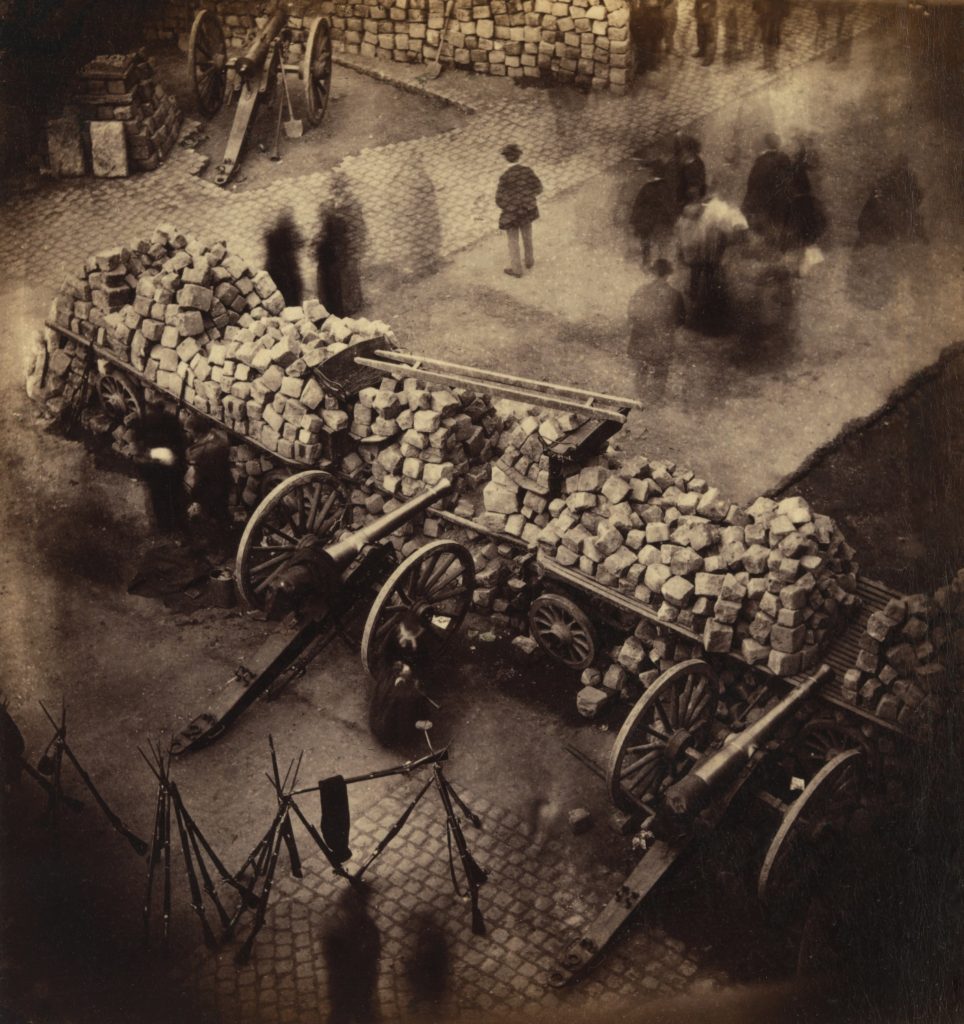

On March 18, Thiers sent troops into Paris to retake 400 cannons under National Guard control. For the Guard, these guns were symbols of the independent power of Paris and its revolutionary people.11 Initially, everything went according to plan and the soldiers seized the cannons. However, no one thought to bring horses to carry away the heavy weapons. So the soldiers waited, but word spread across Paris that they were being disarmed. The population gathered around the soldiers – who were miserable, demoralized and tired of war. Lissargaray describes how this confrontation led to the outbreak of the revolution:

As in our great days, the women were the first to act. Those of the 18th March, hardened by the siege — they had had a double ration of misery — did not wait for the men. They surrounded the machine guns, apostrophized the sergeant in command of the gun, saying, ‘This is shameful; what are you doing there?’ The soldiers did not answer. Occasionally a non-commissioned officer spoke to them: ‘Come, my good women, get out of the way.’ At the same time a handful of National Guards, proceeding to the post of the Rue Doudeauville, there found two drums that had not been smashed, and beat the rappel. At eight o’clock they numbered 300 officers and guards, who ascended the Boulevard Ornano. They met a platoon of soldiers of the 88th, and, crying, Vive la République! enlisted them. The post of the Rue Dejean also joined them, and the butt-end of their muskets raised, soldiers and guards together marched up to the Rue Muller that leads to the Buttes Montmartre, defended on this side by the men of the 88th. These, seeing their comrades intermingling with the guards, signed to them to advance, that they would let them pass. General Lecomte, catching sight of the signs, had the men replaced by sergents-de-ville, and confined them in the Tower of Solferino, adding, ‘You will get your deserts.’ The sergents-de-ville discharged a few shots, to which the guards replied. Suddenly a large number of National Guards, the butt-end of their muskets up, women and children, appeared on the other flank from the Rue des Rosiers. Lecomte, surrounded, three times gave the order to fire. His men stood still, their arms ordered. The crowd, advancing, fraternized with them, and Lecomte and his officers were arrested.12

After the mutiny, Generals Claude Martin Lecomte and Jacques Léonard Clément-Thomas were executed by their own men (despite efforts by the National Guard to prevent the executions). Those soldiers who did not join the revolutionary crowd escaped from the city and retreated to Versailles. Now the Central Committee of the National Guard was the sovereign power in Paris. However, the exhilaration of revolutionary triumph would prove to be short-lived, as a civil war was about to begin.

The Weakness of the Commune and National Guard

On the morrow of the revolution, Blanquists in the National Guard, such as Émile Duval, argued for an immediate offensive against Versailles. The Blanquist Gaston Da Costa wrote in retrospect, “political and social revolution still lay in the future. And to accomplish it the assembly that had sold us out had to be constrained by force or dissolve…. It would not be by striking it with decrees and proclamations that a breach in the Versailles Assembly would be achieved, but by striking it with cannonballs.” 13 The Blanquists argued that the counterrevolution had to be militarily defeated before any lasting social change could occur. The chances for a swift Commune victory appeared promising since they possessed a potential military force of nearly 200,000 National Guardsmen.14

According to the historian Alistair Horne, Versailles no longer had many loyal National Guard units under their command: “the ‘reliable’ units of the National Guard in Paris, which under the siege had once numbered between fifty and sixty battalions, could now be reckoned at little more than twenty; compared with some three hundred dissident battalions, now liberally equipped with cannon.”15 Thousands of regular troops were still German POWs, while those remaining to Versailles lacked discipline and there was a danger of them being susceptible to revolutionary propaganda. Despite the National Guard’s disorganization, their enemy was in even worse state and a swift blow could topple them. Instead of going on the attack, the National Guard relinquished their power and called for an election on March 26 to legalize their revolution by electing a commune. On March 30, the Commune abolished conscription and the standing army.

With an offensive now ruled out, the Commune began negotiations with Versailles hoping to avoid bloodshed and secure municipal liberties.16 This was a forlorn hope since Thiers and Versailles recognized at the very onset that this conflict was a civil war and only side or the other would triumph. Moderates in both the Commune and the National Assembly made several futile, almost comical, efforts to broker a compromise. The negotiations and the Commune’s indecisiveness gave Thiers valuable time to rearm, organize, and negotiate with the Prussians to release French POWs and bolster his forces.

At the beginning of April, Versailles began skirmishing on the outskirts of Paris. The population was roused to a feverish state and was eager to fight. The majority of generals, including the Blanquists Duval and Eudes, supported an offensive sortie to take Versailles. After much hesitation, the Commune launched their first offensive in April, but Versailles was more than ready: “Thiers, having scraped the bottom of the barrel, having brought in Mobiles from all over the provinces and mobilized the gendarmes and ‘Friends of Order’ National Guards [National Guard members loyal to Versailles] escaped from Paris, managed to muster over 60,000 troops at Versailles.”17 By contrast, Lissaragay describes the deplorable state of the National Guard: “They neglected even the most elementary precautions, knew not how to collect artillery, ammunition-wagons or ambulances, forgot to make an order of the day, and left the men for several hours without food in a penetrating fog. Every Federal chose the leader he liked best. Many had no cartridges, and believed the sortie to be a simple demonstration.”18 The National Guard was poorly-led, organized and lost the battle.

Now, Versailles besieged Paris, cordoning off the city from the rest of the country as they amassed troops for an assault. If the Commune was to survive, they needed to create a centralized and organized army to challenge Versailles. Potentially, the Commune had a popular army who were willing to fight for a political and social ideal to the last drop of blood. The problem was that this energy could not be channeled into an effective fighting force. However, in two months, the Commune went through five War Delegates who could not overcome the inherent disorganization of the National Guard and implement an agreed-upon strategy. No leadership was forthcoming from the ruling Communal Council who were divided into several competing factions – Jacobins, Blanquists, Internationalists, and Proudhonists. The Blanquists and Jacobins supported tighter security, centralization and an emergency dictatorship to wage war, while the Proudhonist majority (and many Internationalists) opposed and any thought of “Jacobin centralism.” The Commune’s lack of leadership, inconsistent strategy and factionalism all served to benefit Versailles:

Thus, from the day it assumed office, the danger was apparent that the Commune might be overloaded, indeed overwhelmed, by the sheer diversity of desires as represented by so polygenous a multitude of personalities, ideologies, and interests. And there was no obvious leader to guide the multitude. Had Blanqui been there, it might have been quite a different story. But Blanqui was securely in the hands of Thiers, while Delescluze, the only other possible leader, was so ailing that he would have preferred nothing better than to have retired from the scene altogether. Thiers, it now seemed, had at least made two excellent initial calculations; one was the seizure of Blanqui, and the other had been to force the Communards to commit themselves before either their plans or their policy had time to crystallize.19

Following the April victory, Thiers tightening the noose around Paris. The Commune never overcame its weaknesses and broke the siege. In late May, a French Army of 170,000 men moved into Paris and crushed the revolution in a horrendous bloodbath that killed at least 20,000 Communards.

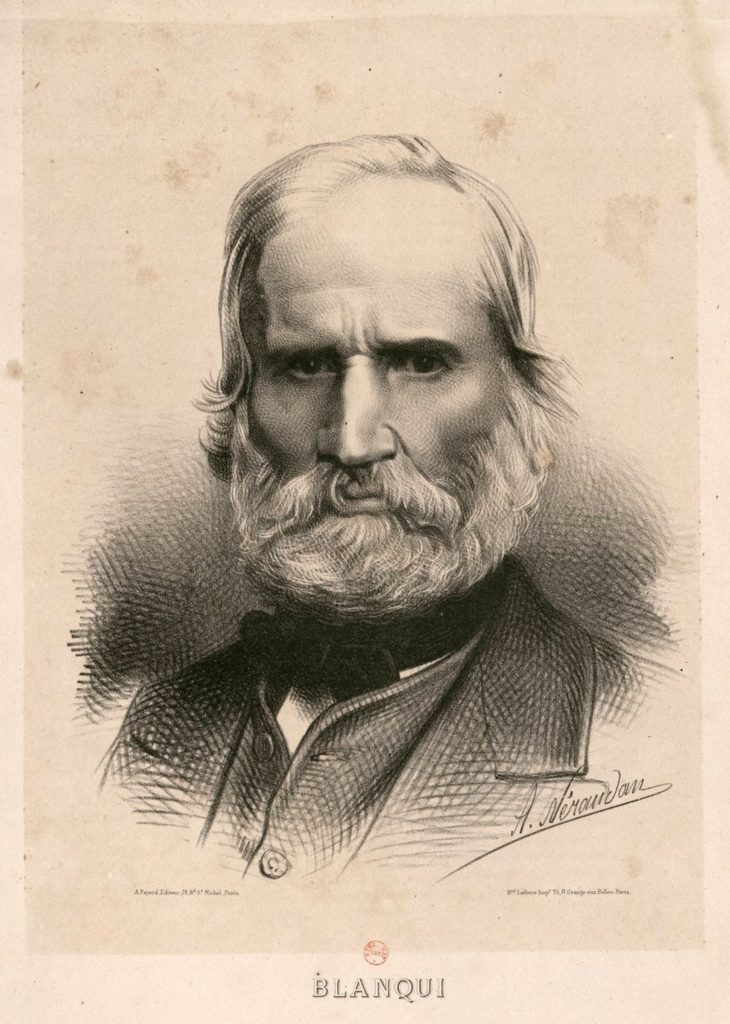

Louis-Auguste Blanqui

Could the Commune’s fate have been avoided? The presence of the sixty-six-year-old Louis-Auguste Blanqui could have changed everything. Blanqui (1805–1881) was one of the most revered, dedicated, and uncompromising communist revolutionaries of nineteenth-century France. He had participated in five abortive revolutions from 1830 to 1870. Blanqui’s revolutionary strategy was decidedly simple: a secret conspiracy, highly organized in a hierarchical cell structure and trained in the use of arms and the clandestine arts, would rise up on an appointed day and seize political power in Paris. Once the revolutionaries had power, they would establish a transitional dictatorship which would accomplish two things: serve as a police force “of the poor against the rich” and educate the people in the virtues of a new society. Once these twin tasks were completed, the dictatorship would give way to a communist society. Every French government since 1830 had seen fit to lock him up, hoping to silence his uncompromising voice of class war. Despite constant failure and imprisonment, Blanqui emerged from the dungeons every time to continue fighting.

Blanqui was mainly a man of action with no coherent theory, but a mishmash of eclectic ideas. Despite his theoretical weaknesses, Blanqui did have a keen grasp of insurrectionary tactics that came from his long days as a Parisian street-fighter. In 1868, Blanqui wrote a treatise on urban warfare, Manual for an Armed Insurrection. Blanqui had a thorough knowledge of the methods of street fighting, understanding the importance of organization: “There must be no more of these tumultuous uprisings of ten thousand isolated heads, acting randomly, in disorder, with no thought of the whole, each in his own corner and according to his own fantasy.”20 Organization, coordination, and concern for the larger picture would replace disorder, randomness, and individualism if a revolutionary insurrection was to prevail. He knew that insurgents who are motivated by an idea can be more than a match for a better-armed adversary: “In the popular ranks…what drives them is enthusiasm, not fear. Superior to the adversary in devotion, they are much more still in intelligence. They have the upper hand over him morally and even physically, by conviction, strength, fertility of resources, promptness of body and spirit, they have both the head and the heart. No troop in the world is the equal of these elite men.”21 Blanqui’s ethic is – if you lack the will to win or hesitate in carrying out what the revolution demands of you, not only will you lose, but you are a traitor to the cause you claim to serve. These lessons were not understood by the Paris Commune.

Yet Blanqui’s approach to revolution was voluntaristic – neglecting the role of the masses in their own liberation and placing almost superhuman faith in the ability of arms and organization to succeed, regardless of the objective conditions. He wrote once that “Armament and organization, these are the decisive agencies of progress, the serious means of putting an end to oppression and misery.”22 He believed that due to the unstable contradictions of bourgeois society that revolution could be launched at any time, provided there was a combat organization with a clear plan of battle and the will to win against insurmountable odds can unveil unseen roads to communism.

However, Blanqui was not simply a man of action and an insurrectionist, but a symbol. Alain Badiou argued that emancipatory politics is “essentially the politics of the anonymous masses,” it is through proper names such as those of Blanqui where “the ordinary individual discovers glorious, distinctive individuals as the mediation for his or her own individuality, as the proof that he or she can force its finitude. The anonymous action of millions of militants, rebels, fighters, unrepresentable as such, is combined and counted as one in the simple, powerful symbol of the proper name.”23

For members of the ruling class like Alexis de Tocqueville, he was the very personification of the radicalism of the dangerous classes who threatened their property. When de Tocqueville first saw Blanqui, his very appearance “filled me with disgust and horror. His cheeks were pale and faded, his lips white; he looked ill, evil, foul, with a dirty pallor and the appearance of a mouldering corpse… he might have lived in a sewer and just emerged from it.”24 According to the novelist Victor Hugo, Blanqui was “no longer a man, but a sort of lugubrious apparition in which all degrees of hatred born of all degrees of misery seemed to be incarnated.”25 Blanqui was a specter whose every word and deed portended the end of order, property, and privilege. Marx recognized that Blanqui was a symbol of terror to the capitalist class and the beacon of hope for the working class: “the proletariat rallies more and more around revolutionary socialism, around communism, for which the bourgeoisie has itself invented the name of Blanqui.”26

The Blanquist Party

During the latter days of the Second Empire, Blanqui’s revolutionary vision and stature attracted many workers and students who formed conspiratorial organizations to bring down the government. The Blanquists launched two failed coup attempts in August and October of 1870. When the Commune was proclaimed, they had members in the National Guard and the Communal Council. They were seemingly well-positioned to play a commanding role in the Commune. So what happened?

For one, they lacked the leadership of Blanqui himself who was in one of Thiers’ jails for the duration of the Commune. Yet only a few months before in September and October of 1870, Blanqui had offered “critical support” for the Republic’s war effort in his journal La Patrie en Danger. Blanqui’s support for the Third Republic confused and disoriented his party. According to the Blanquist militant Da Costa argues, “We cannot say this often enough: since the besieging of Paris by the Prussians, the Blanquist party had sent its men into the battalions of the National Guard, and in doing so lost all cohesion…. Blanqui’s cry of ‘the fatherland in danger,’ as meritorious as it was, was also a disintegrating factor for the revolutionary forces it disposed of until then.”27

Blanqui wanted a more vigorous military effort with a levée en masse and the creation of a revolutionary regime like the Jacobins to fight the Prussians. However, the Republic was unwilling and unable to implement these measures, so Blanqui turned against it and participated in a failed coup attempt of October 1870.28 When the coup collapsed, the Republic placed a bounty on his head and had to go into hiding. Eventually, Blanqui was captured by Versailles on March 17, the day before the foundation of the Commune. In a cruel twist of fate, Blanqui missed the revolution which he had worked for decades to achieve and his party was left leaderless at the critical hour.

Although the Blanquists held several leadership positions within the Commune and the National Guard, the historian Patrick Hutton says they “did not act as a consolidated interest group.”29 Without Blanqui at the helm, his party was incapable of acting effectively and decisively. The Blanquists failed to convince the Commune to in launch a first strike against Versailles,. They also lost their chance to take military leadership of the Commune during the opening days. The Blanquist general Eudes proposed constructing a revolutionary army led by Blanquist commanders (Duval, Chauviere, Ferre, and himself), but this plan was quashed by the Central Committee of the National Guard.30

Secondly, the Blanquist faction’s proposed emergency measures to fight Versailles were resisted by the Communal Council – who believed these would violate the principles of the revolution and democracy by instituting a one-man dictatorship and Jacobin terror. As the military situation continued to worsen during April, the calls grew louder from many outside the Blanquist ranks to create a Committee of Public Safety – harkening back to its 1793 predecessor which saved the First Republic from foreign invaders and counterrevolutionaries. It was hoped that the success of the original Committee of Public Safety could be repeated. Eventually, a majority on the Communal Council supported the creation of a Committee of Public Safety.31 However, it was not led by capable men who did not use the unlimited powers theoretically at their disposal. Instead, the Committee of Public Safety added to the organizational confusion of the Commune and was unable to prevent the final debacle.

On top of its own organizational difficulties, the Commune had to contend with real threats of subversion and deal with a hostile press. While many Communards believed repressive organs were unnecessary, the Blanquist Raoul Rigault who headed the Communards’ police force knew stern measures were needed to combat the counterrevolution. Rigault was a seemingly unlikely police chief, who began his political life during the Second Empire as a young flamboyant Bohemian and atheist militant in the Parisian student quarter. Yet he managed to expose police informers in the Blanquist organization of the 1860s. Blanqui praised Rigault’s talents: “He is nothing but a gamin, but he makes a first-rate policeman.”32 When Rigault banned four hostile papers on April 18: Le Bien Public, Le Soir, La Cloche, and L’Opinion, his actions were protested in the Communal Council and led to calls for his resignation, but he managed to stay on. Rigault went after suspected counterrevolutionaries such as the clergy and investigated monasteries and churches, believing that they held arms and hidden treasure. However, these repeated searches turned up nothing substantive. Although Rigault possessed a fierce revolutionary drive to do what the situation required, he was viewed by many as a “lazy and conceited, a man who reveled in the perquisites of office without being willing to face the responsibilities… Rigault continued to pass his afternoons in the cafes of the Left Bank, as had long been his custom, and left the bulk of the work to his subordinates.”33 Rigault’s fervor was not shared by the majority of the Commune and there was no structure to utilize him, so his talents were left without effective direction.

Rigault and the rest of the Blanquists recognized the fatal weaknesses afflicting the Commune and believed that the imprisoned Blanqui could overcome them and lead the revolution to victory. To that end, Rigault spared no effort to free Blanqui and once declared that: “Without Blanqui, nothing could be done. With him, everything.”34 Blanqui’s prestige extended far beyond the Blanquists, the rest of the Commune viewed him with awe. Initially, he was elected to the Communal Council (in absentia) and there was a motion in the Commune to make him honorary President (instead that honor fell to Charles Beslay).35 After these failures, the Commune negotiated with Versailles to free Blanqui, offering the Archbishop of Paris, their most valuable hostage in exchange. Thiers refused and the Communards made a desperate offer to trade all 74 hostages in exchange for Blanqui. Thiers did not budge. Karl Marx said that for Thiers, it was a wise decision to keep Blanqui under lock and key: “The Commune again and again had offered to exchange the archbishop, and ever so many priests into the bargain, against the single Blanqui, then in the hands of Thiers. Thiers obstinately refused. He knew that with Blanqui he would give to the Commune a head…”36 In the end, Blanqui remained in jail as his comrades were massacred on the streets of Paris.

Despite the Blanquists occupying a number of key positions, they were unable to act in a coordinated or decisive manner to shape either the Commune’s military strategy or its political policies. Without Blanqui, no one in his party possessed the same stature to provide the needed leadership and discipline.

The Choice

If Blanqui had managed to avoid arrest on March 17, what would he have done at the Paris Commune? Based on what know, Blanqui would have argued for a first strike against the routed and demoralized forces of Versailles. The brief window of two weeks before Versailles reorganized in early April was the one time when the Commune had a clear military advantage. Marx lamented that the Commune failed to go on the offensive:

If they are defeated only their ‘decency’ will be to blame. They should have marched at once on Versailles, after first Vinoy and then the reactionary section of the Paris National Guard had themselves retired from the battlefield. The right moment was missed because of conscientious scruples. They did not want to start a civil war, as if that mischievous abortion Thiers had not already started the civil war with his attempt to disarm Paris! Second mistake: The Central Committee surrendered its power too soon, to make way for the Commune. Again from a too ‘honourable’ scrupulousness!37

Blanqui knew that at the beginning of an insurrection, it was necessary to take the offensive or risk losing everything. While other Blanquists were ignored when they made the same case to the Commune and the National Guard, they may have listened to Blanqui with his tremendous moral authority. The National Guard did not attack when it had the advantage over a completely disorganized adversary, and the Blanquists were uncoordinated and leaderless. Blanqui’s presence and leadership could have provided the missing link needed to sway the National Guard and lead the Blanquists to launch an immediate offensive which could well have succeeded.

There has been endless speculation by historians on whether the Commune could have succeeded considering its own manifold disorganization and the forces arrayed against it and on Blanqui’s potential role in the revolution. Hutton argues that the Blanquist hope in their leaders was “a temptation to fantasy. In clinging to a myth of the Commune’s enduring viability in the face of its obvious failings, the Blanquists passed the frontier into that imaginary land wherein they could fulfill the aspirations of their aesthetic reverie free from the intrusion of harsh realities.”38

However, others beyond the ranks of the Blanquists have also stated that Blanqui could have provided the necessary leadership to overcome the divisions which plagued the Commune. For instance, the Communard Minister of War Gustave-Paul Cluseret who believed that: “If Blanqui were at Paris he might save the Commune. He would have taken the political conduct of affairs into his own hands, and have left me free to devote myself to the military defence of Paris. Accustomed to discipline, he would have disciplined his people, and would have allowed me to discipline mine.”39 The French historian, Maurice Dommanget, author of innumerable works on Blanqui, speculates that his presence at the Commune could have proven decisive: “With his organizational and military abilities, with his lucidity, the prestige that was attached to his name, Blanqui would rapidly have become the leader and the spirit of the insurrection. Jaclard believes that he would have the necessary resolution and sufficient authority to command the march on Versailles on March 19, this would obviously change the face of things.”40

Many Marxists have argued that Blanqui was the natural leader of the Commune. As mentioned above, Marx saw Blanqui as the Commune’s head. The Marxist Victor Serge lamented Blanqui’s absence from Paris: “The misfortune of Blanqui, a prisoner during the Commune, the head of the revolution cut off and preserved in the Chateau du Taureau at the very moment when the Parisian proletariat lacked a real leader, still troubled us as the worst kind of ill luck.”41 While Blanqui had little military experience beyond conspiratorial organization and street fighting, but then again, how much training did Leon Trotsky have when he organized the October Revolution and the Red Army?

The Belgian Trotskyist Ernest Mandel says Blanqui was not only “ the greatest French revolutionary of the 19th century” but added:

Everyone, including Karl Marx, considered him the natural leader of the Commune, in which his followers formed a minority around Vaillant. The Paris-based revolutionary government proposed to Thiers that he be freed in exchange for the release of all the Commune’s hostages, including the archbishop of Paris. But Thiers refused, demonstrating the extent to which the French bourgeoisie feared the organisational and leadership capacities of the great revolutionary, and the impact his political gifts could have had on the outcome of the civil war.42

Assuming that Blanqui was able to lead the Commune to victory over Versailles, this is only the beginning of their struggles. Here we enter the realm of pure speculation. A triumphant Commune would have to win over the rest of France. In reality, there were other communes in France in 1871, but they were revolutionary islands surrounded by a hostile countryside and peasantry opposed to the “Reds” and continuation of the war. If the Commune held onto power, they faced a prospect of renewed war with Prussia, which could be even bloodier. They would need to win over enough of the general staff, and although many of the officers may have opposed the Red Revolutionaries, they may have supported a new government committed to doing everything possible to achieve victory. Perhaps, Blanqui’s Commune would become a “French Yenan” – a liberated zone which rallies the people in arms against a foreign invader. Yet the needs of fighting a war would mean that those alternative voices for social change such as radical workers, Proudhonists and Internationalists would likely be drowned out (or perhaps silenced by a new Committee of Public Safety?). It seems unlikely that the Commune’s advanced social ideas would survive the grim trial of war, assuming France prevailed at all.

Any victory for a Blanquist-led Commune would not have been a triumph for the socialist aspects of the Commune. Blanqui and his followers saw the Commune as a repetition of the Paris Commune of 1793, and not as the beginning of modern socialist politics. The Blanquists neither appreciated nor understood the socialist potential of the Commune. They failed to recognize the creative aspects of proletarian self-emancipation and mass organization which it represented. Blanquists such as Gaston Da Costa denied any socialist possibility for the Commune:

The insurrection of March 18 was essentially political, republican, patriotic, and, to qualify it with just one epithet, exclusively Jacobin… It is nevertheless impossible to argue that socialist ideas, if not doctrines, were not spoken of within the assembled Commune, but these affirmations remained verbal, platonic, and in any case foreign to the 200,000 rebels who on March 18, 1871, slid cartridges into their rifles in indignation. If they had truly been socialist revolutionaries, which our good bourgeois like to believe, and not indignant Jacobin and patriotic revolutionaries, they would have acted completely differently…. Neither Blanqui, if he would have led us, nor his disciples dreamed of creating this environment in 1871. At that time the Blanquists were the only thing that they could be: Jacobin revolutionaries rising up to defend the threatened republic. The idealist socialists assembled in the minority were nothing but dreamers, without a defined socialist program, and their unfortunate tactics consisted in making the people of Paris and the communes of France believe that they had one.43

While the Commune echoed back to the Jacobins by reviving the revolutionary calendar and creating its own Committee for Public Safety, it also marked the entry of the working class onto the stage of history as an independent actor. In this sense, the Commune was a harbinger of the future. The Blanquists could only commemorate, venerate and honor the revolution of 1871 as a holy relic like they did with the bourgeois revolution of 1789. For socialist revolutionaries such as Franz Mehring, the Commune raised new questions of socialist politics and mass working class organization far different than those of Blanquist conspiracies:

The history of the Paris Commune has become a touchstone of great importance for the question: How should the revolutionary working class organize its tactics and strategy in order to achieve ultimate victory? With the fall of the Commune, the last traditions of the old revolutionary legend have likewise fallen forever; no favorable turn of circumstances, no heroic spirit, no martyrdom can take the place of the proletariat’s clear insight into…the indispensable conditions of its emancipation. What holds for the revolutions that were carried out by minorities, and in the interests of minorities, no longer holds for the proletariat revolution…In the history of the Commune, the germs of this revolution were effectively stifled by the creeping plants that, growing out of the bourgeois revolution of the eighteenth century, overran the revolutionary workers’ movement of the nineteenth century. Missing in the Commune were the firm organization of the proletariat as a class and the fundamental clarity as to its world-historical mission; on these grounds alone it had to succumb.44

For revolutionaries such as Lenin, the many errors and missteps of the Commune – not crushing the counterrevolution, not organizing a disciplined party and army, building an alliance with the peasantry, or taking the commanding heights of the economy – were studied so that they would not be repeated. The example of 1871 enabled the Russian Revolution of 1917 to succeed: “without the lessons and legends derived from the Commune, there would probably have been no successful Bolshevik Revolution of 1917…”45 Lenin had a good reason for dancing in the snow when the Soviet Republic reached its 73rd day and outlasting the Commune.

Although Blanqui and his party did not grasp the Commune’s socialist potential, they do represent a choice that could have won a military victory. Whatever the faults of Blanqui, he understood that revolutionaries must launch a swift offensive to win. If Blanqui was present at the Commune with his leadership, revolutionary will, and moral standing, he would have championed that option.

- Rosa Luxemburg, “Order Reigns in Berlin,” in Rosa Luxemburg: Selected Political Writings, ed. Dick Howard (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1971), 413-414.

- For a more in-depth discussion on Lenin and Trotsky’s ideas on insurrection my “Leninism and Blanquism,” Cultural Logic (2012): http://clogic.eserver.org/2012/Greene.pdf ; “Leon Trotsky and Revolutionary Insurrection,” LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal. http://links.org.au/node/3637

- The literature on the Commune is vast. For a sampling see Karl Marx, “The Civil War in France,” Marx and Engels Collected Works 22 (London: Lawrence & Wishart), 307-357. (henceforth MECW); Donny Gluckstein, The Paris Commune: A Revolution in Democracy (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2011); Robert Tombs, The Paris Commune 1871 (New York: Longman, 1999).

- Quoted in Frank Jellinek, The Paris Commune of 1871 (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1965), 65.

- Tombs 1999, 51.

- Edith Thomas, The Women Incendiaries (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2007), 38-9.

- Gluckstein 2011, 86-7.

- Pierre-Olivier Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871 (St. Petersburg, Florida: Red and Black Publishers, 2007), 62.

- Ibid. 67.

- Tombs 1999, 65.

- Ibid. 67.

- Lissagaray 2007, 72. See also Jellinek 1965, 109-126. Other first-hand accounts of the March 18th uprising can be found in The Communards of Paris, 1871, ed. Stewart Edwards (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1973), 56-65. For the role of women in the March 18th revolution see Thomas 2007, 52-69.

- Quoted in Gluckstein 2011, 117.

- In actuality, no more than 30,000 National Guard were actually battle ready. See Alistair Horne, The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870–71 (New York: Penguin Books, 1990), 329.

- Ibid. 280.

- For Duval’s call for an immediate offensive see Gluckstein 2010, 118. The official program of the Commune issued on April 19 and written by the Proudhonist Pierre Denis claimed that Paris merely wanted municipal reforms and decentralization. For the program see “Declaration to the French People” in Edwards 1973, 81–3. The program was hastily written and passed without debate: “This assembly, which gave four days to the discussion on overdue commercial bills, had not one sitting for the study of this declaration, its programme in case of victory, its testament if it succumbed” (Lissagaray 2007, 163).

- Horne 1990, 306.

- Lissagaray 2007, 137.

- Horne 1990, 299-300.

- Blanqui, “Manual for Armed Insurrection,” Marxists Internet Archive. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/blanqui/1866/instructions1.htm

- Ibid.

- Louis-Auguste Blanqui, “Warning to the People,” Marxists Internet Archive. http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/blanqui/1851/toast.htm

- Alain Badiou, The Communist Hypothesis (New York: Verso, 2010), 249-50.

- Alexis de Tocqueville, Recollections of Tocqueville (New York: Columbia University Press, 1949), 130.

- Victor Hugo, Memoirs of Victor Hugo (London: William Heineman, 1899), 292.

- “Class Struggles in France, 1848-1850” MECW 10.127.

- Da Costa, “The Commune Lived,” in Communards: The Story of The Paris Commune of 1871 As Told by Those Who Fought for It, ed. Mitchell Abidor (Pacifica CA: Marxists Internet Archive, 2010), 173.

- For Blanqui’s writings on a more vigorous war effort see Louis-Auguste Blanqui, “La Patrie En Danger,” in Abidor 2010, 38–49. For the background of the October coup see Horne 1990,102–20.

- Patrick Hutton, The Cult of Revolutionary Tradition: The Blanquists in French Politics, 1864–1893 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981), 72.

- Ibid. 73.

- Gluckstein 2011, 142, and Hal Draper, Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution, Volume 3: The “Dictatorship of the Proletariat” (New York: Monthly Review Press: 1986), 277–78.

- Quoted in Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), 618.

- Hutton 1981, 75.

- Ibid. 338.

- Ibid. 300.

- “Civil War in France,” MECW 22.352.

- “Marx to Ludwig Kugelmann, April 12, 1871,” MECW 44.132.

- Hutton 1981, 169.

- Quoted in James Anthony Froude, ed., Fraser’s Magazine: New Series. Volume VI (London: Longsmans, Green, and Co., 1872), 796.

- Maurice Dommanget, Blanqui (Paris, Etudes et documentation internationales, 1970), 80. (my translation)

- Victor Serge, From Lenin to Stalin (New York: Monad Press, 1973), 10.

- Ernest Mandel, The Place of Marxism in History (Amherst: Humanity Books, 1999), 48.

- Gaston Da Costa, “The Commune and Socialism,” in Abidor 2010, 174-181.

- Quoted in Benjamin 1999, 788.

- Horne 1990, 15.