In a debate on labor strategy, Kat and Chantelle argue for the merger of political, economic, and theoretical struggles; for boring from within the reactionary unions; for open communist leadership within a reformist context; and for tactical flexibility. Kat and Chantelle are members of Maoist Communist Union (MCU) and Teamsters Mobilize. They can be reached at maoistcommunistunion@riseup.net.

This article is both inspired by and a response to “Some Preliminary Theses on Communist Work in the Labor Movement” and “Further Discourse on Communist Activity in the Labor Movement and the State Unionism Thesis” by Comrade Saoirse of the Revolutionary Maoist Coalition (RMC), and was composed after a member of RMC asked for our thoughts on these pieces.

We are glad to be participating in the debate over the line for communist work in the unions and in the working class movement as a whole. It is essential that communists seriously study and debate these questions, as the lack of clarity on these topics has been a serious barrier to building communist organization and providing leadership to the working class movement in the US.

MCU has published two documents on these questions and how our positions as an organization have changed over time: “Some General Theses on Communist Work in the Trade Unions” and “MCU and the Working-Class Movement.”

On the whole, we agree with many of the points made by Comrade Saoirse. We hold secondary disagreements and criticisms, which we elaborate on below, but think that her contributions are positive in clarifying the role of communists in the unions.

The labor movement, or the working class movement

Comrade Saoirse’s third thesis is: “The labor movement by itself — i.e. trade unionism, economism, syndicalism — will not liberate the proletariat.” We unite with what we believe to be the core sentiment of this statement, namely that participation in union struggles under capitalism is not enough for the working class to overthrow the bourgeoisie and establish the Dictatorship of the Proletariat.

However, while the currently existing “labor movement” in the US is for the most part limited to the economic labor union movement, and although ostensibly “communist” participation in this movement is mired in economism (defined and explained below in this article), we do not think it makes sense to equate: 1) the labor movement as a whole with “trade unionism, economism, syndicalism,” 2) the economic struggle of the class with economism, nor 3) syndicalism with either trade unionism or economism. Our aim in this section is to explain each of these points of disagreement in turn.

First, we should not equate the labor movement with the labor union movement. Historically, especially outside the US, “labor movement,” “proletarian movement,” “workers’ movement” and “working class movement” have been used interchangeably to refer to the whole movement of labor against capital, in all its dimensions. But in the US today, many groups and individuals across the left-liberal spectrum, typically think of the “labor movement” as just the labor union struggle.1 Unfortunately, this practice is common among communists in this country as well; we in MCU also fell into this practice until fairly recently. This reduction of the labor movement to union struggles is a fundamentally bourgeois conception that we must break from. The bourgeoisie comes to acknowledge the existence of a “labor problem” in society, and they even create ministries and departments of “Labor” or institutions like the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to take on this “problem.” However, these institutions generally explicitly limit the scope of “Labor” to workplace issues, wages, and basic rights to organize unions. In this way, the bourgeoisie and its state constantly reinforce the idea that these narrowest of economic concerns are the only concerns around which the workers can hold a shared interest as a class. We must instead emphasize to the workers that labor has to concern itself with all social questions, especially the fundamental question of which class holds political power (i.e., which class has the ability overall to dictate its policy in a general form possessing “social force of compulsion,” as Marx put it).2

In 1874, Engels identified the practical economic struggle – which is conducted by and large by the unions – as one of the three aspects of the working class movement as it existed in Germany at the time (emphasis ours):

It must be said to the credit of the German workers that they have utilised the advantages of their situation with rare understanding. For the first time in the history of the labour movement the struggle is being so conducted that its three sides, the theoretical, the political and the practical economical (opposition to the capitalists), form one harmonious and well-planned entity. In this concentric attack, as it were, lies the strength and invincibility of the German movement.3

The economic struggle (what Engels calls the “practical-economic” struggle) is generally the first side of the workers’ movement to develop, because it can be carried out at the local level and without a high level of pre-existing, widespread class consciousness. It is the struggle of the workers in their day-to-day fights against individual capitalists for improvements (or, quite often, against degradation) of wages and working conditions. A given economic struggle can be waged on the level of a single workplace (such as the recent efforts by Starbucks employees to unionize), a single trade, or even an entire industry (as in the 2023 UAW strike against the “Big Three” US auto manufacturers). The level of development (including fighting spirit, discipline, organization, and clarity on how to advance the struggle) of the working class in the economic struggle varies across time and space. Compare, for instance, the state of the national economic movement of the working class in the US in 1987 – when union density was on a sharp decline following the turn of the US ruling class towards neoliberal policies much more hostile to organized labor – with the conditions 50 years prior in the same country, when industrial workers were flooding into unions by the millions. Alternatively, we can juxtapose the US proletarian economic struggle circa 1987 with that in South Korea in the same year, where a massive and militant strike wave by the Korean industrial proletariat was taking place in the context of broader opposition to the ruling military dictatorship there. Across this entire spectrum of conditions, the economic struggle is an ever-present, unavoidable, and essential aspect of the working class movement under capitalism which communists must provide leadership to.4 So long as the proletariat is exploited and oppressed by the capitalists, so long as workers are forced to sell their labor power to the capitalists in order to survive, they will and must fight against the abuses, misery, and poverty they face by virtue of this fact. The unions are the most basic and broad organization with which to wage such fights.

The political struggle of the proletariat is one in which workers, as a class, fight for demands that serve the interests of the class as a whole. As Marx said,

Every movement in which the working class, as a class, opposes the ruling classes and seeks to compel them by ‘pressure from without’ is a ‘political movement.’ For example, the attempt to obtain forcibly from individual capitalists a shortening of working hours in some individual factory or some individual trade by means of a strike, etc., is a purely economic movement. On the other hand a movement forcibly to obtain an eight-hour law, etc., is a political movement. And in this way a political movement grows everywhere out of the individual economic movement of the workers, i.e., a movement of the class to gain its ends in a general form, a form which possesses compelling force in a general social sense.5

The political struggle is a higher level of the proletariat’s struggle as it can only arise when the workers understand that in order to advance their interests (short-term and long-term), they cannot limit their fight to specific employers or only certain sections of the capitalist class, but that they must fight against the entire capitalist class, including against the capitalist state machinery. There are, of course, different types of political struggles; there are variations in demands and political character of these struggles. The type of movement Marx describes in the previous quote, namely a fight to prescribe limitations on the length of the working day within the bourgeois legal code, is a political extension of union demands.6

However, the political struggles of the working class do not only develop directly from extensions of labor union demands. Some arise directly from various social issues,7 and others begin as political struggles which are extensions of union demands, but escalate into revolutionary struggles (i.e. struggles which concern which class is in power and runs the society). The latter happened in Russia in 1914 just prior to the outbreak of the World War.

In his memoir, Old Bolshevik Alexander Shlyapnikov describes how during the July Days of 1914 (not to be confused with the July Days of 1917), the police repression and Cossack cavalry charges against striking workers played a major role in escalating the strike movement from economic to political and ultimately to revolutionary. The initial violence against striking workers (which included the police murder of some of the strikers) who were putting forward economic demands led to a major upsurge in strikes against this police violence. When the Tsarist autocracy tried to, in turn, suppress these strikes by means of further violent repression, the Petersburg Committee of the Bolshevik Party helped to guide the working class movement towards revolutionary demands. Shlyapnikov describes these events vividly:

The protest strike against the violence and the arrests switched from the Narva and Vyborg districts (of St. Petersburg) to Vasiliev Island, the Kolomna district and beyond the Neva Gate, and flooded throughout the city. The newspapers spread the news across Russia, and a response to this powerful movement could be expected from the provinces. From 6 July till 12 July the strike was almost general, and the number of strikers reached 300,000. Meetings and demonstrations took place everywhere, and in some places barricades were erected. Workers sought arms everywhere, and brought up stocks of revolvers and knives to arm themselves somehow against the police and cossacks.8

As class struggle intensifies, the working class is increasingly faced with the question of which class is in power, the antagonism between the bourgeoisie and proletariat, and the need for revolution. Thus, political movements for demands like an 8-hour work day can, in certain circumstances, develop into revolutionary struggles. Generally this happens in circumstances where there is a revolutionary situation in the country in question. This development can be aided by the existence of a sufficiently experienced Communist Party which has a correct line, is theoretically developed, and has large-scale influence in the working class movement.9 Even in the absence of such a Party, it is possible for political struggles to develop into revolutionary struggles, but it is exceedingly unlikely that a revolution would succeed.10

Though it’s important to recognize the economic and political struggles as distinct entities, they are by no means isolated from one another. As the economic struggle develops, the relatively advanced sections of the working class learn the tactics and strategies of the bourgeoisie for squashing organized resistance. Economic struggle also draws in less active sections by “awakening and stirring up the backward” as Lenin wrote in Economic and Political Strikes.11 In this article, Lenin reflects on the strikes in the 1905 Russian Revolution and emphasizes that economic movements lay the foundation for more widespread agitation and action around political demands:

[…] the mass of the working people will never agree to conceive of a general “progress” of the country without economic demands, without an immediate and direct improvement in their condition. The masses are drawn into the movement, participate vigorously in it, value it highly and display heroism, self-sacrifice, perseverance and devotion to the great cause only if it makes for improving the economic condition of those who work. Nor can it be otherwise, for the living conditions of the workers in “ordinary” times are incredibly hard. As it strives to improve its living conditions, the working class also progresses morally, intellectually and politically, becomes more capable of achieving its great emancipatory aims.12

The economic struggle continues to develop and strengthen after political movements emerge. Strikes over demands of a broad-ranging nature, concerning the conditions of the class as a whole in capitalist society, can (especially during particularly acute periods of crisis) rouse the general fighting spirit of the proletariat over all sorts of grievances and outrages, including those limited to a single workplace or trade. Thus, Lenin argued against both the Menshevik liquidators who called for a strict segregation between economic and political struggles, and the mechanical line that the importance of Communists leading the economic struggle fades as the working class commences political struggles.13 In reality, the economic and political struggles exist in dialectical relation to one another, each exerting mutual influence on the other throughout their respective, simultaneous courses of development.

While we have spoken about how strong proletarian economic struggles can serve as the basis for the development of proletarian political struggles, we want to be clear that political struggle does not only arise as an extension of economic struggles. Lenin argues against precisely this economist argument in What is to be Done?:

Is it true that, in general, the economic struggle “is the most widely applicable means” of drawing the masses into the political struggle? It is entirely untrue. Any and every manifestation of police tyranny and autocratic outrage, not only in connection with the economic struggle, is not one whit less “widely applicable” as a means of “drawing in” the masses. The rural superintendents and the flogging of peasants, the corruption of the officials and the police treatment of the “common people” in the cities, the fight against the famine-stricken and the suppression of the popular striving towards enlightenment and knowledge, the extortion of taxes and the persecution of the religious sects, the humiliating treatment of soldiers and the barrack methods in the treatment of the students and liberal intellectuals — do all these and a thousand other similar manifestations of tyranny, though not directly connected with the “economic” struggle, represent, in general, less “widely applicable” means and occasions for political agitation and for drawing the masses into the political struggle? The very opposite is true. Of the sum total of cases in which the workers suffer (either on their own account or on account of those closely connected with them) from tyranny, violence, and the lack of rights, undoubtedly only a small minority represent cases of police tyranny in the trade union struggle as such. Why then should we, beforehand, restrict the scope of political agitation by declaring only one of the means to be “the most widely applicable”, when Social-Democrats must have, in addition, other, generally speaking, no less “widely applicable” means?14

Here Lenin is explaining the fundamental importance of the conscious activity of Marxists in advancing the proletarian movement and raising the level of class consciousness to communist consciousness. He is, above all, explaining how political propaganda—from a distinctly proletarian perspective—is essential to developing the class consciousness of the working class and how this, in turn, prepares the grounds for larger political struggles and, ultimately, for the revolutionary struggle.

The third side of the labor movement is the theoretical struggle. From the beginning of the labor movement, there has been a struggle within it over the correct strategy and tactics to guide it, based on different understandings of class society, including how to evaluate the class interests of the proletariat, the bourgeoisie, and other classes; the role of the state; etc.15

Equipped with this understanding of the component parts of the labor movement, we can return to our criticism of Comrade Saoirse’s articulations in Thesis #3: “[t]he labor movement by itself — i.e. trade unionism, economism, syndicalism — will not liberate the proletariat.” The economic struggle, conducted via the unions, is just one aspect of the labor movement, alongside political and theoretical struggle. The widespread confusion in the US – including amongst communists – on this point reflects the low level of both the US working class movement (where there is, at present, no independent political action by the working class to speak of, and the class movement is limited to the economic sphere) and of communists in this country (who have been plagued by left and right deviations and a low level of theoretical clarity, particularly around these foundational questions, for decades). We emphasize the difference between the labor movement and its economic aspect not to quibble over semantics, but in order to inform a sound evaluation of correct strategy and tactics across different situations. If we misunderstand the aspects of the working class movement and the relations between them, we are bound to misunderstand our tasks with regard to them.

Our second disagreement with Thesis #3 is what we understand to be its equation of participation in the economic struggle of the workers with economism. Economism, as Lenin writes about in What is to be Done?, is the right opportunist deviation amongst Marxists of overemphasizing the economic struggle in the working class movement; of reducing working class politics to trade unionist politics; of putting off political education and exposures – one of the primary ways we bring Marxism to the working class – until some undetermined, far-off date, once the economic struggle has developed to a sufficient degree. This is the most common deviation amongst US communists today, and one that we in MCU have consistently had to combat within our own ranks, given the dominance of bourgeois ideology in our society.

This is an important distinction, because if economism is a right-opportunist deviation and something to struggle resolutely against, and if we conflate participation in the economic struggle of the working class with economism, then it would follow that communists should only concern ourselves with, support, and lead the political struggle of the working class (and perhaps even oppose the economic struggle of the workers as backwards or unnecessary). While economism is the most prevalent deviation amongst US communists today, the “left” deviation to excessively belittle the importance of the workers’ economic struggle in the unions – and of communists providing leadership to it – is still a relatively common error within Maoist circles specifically. This is unfortunate but fairly unsurprising given the decades of history of Maoists in the US, particularly the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP), labeling work in the unions as economist.16 In order to maintain course along a proletarian line, we must participate in struggles for economic reforms, while still – as Lenin described in What is to be Done? – “subordinate the struggle for reforms, as the part to the whole, to the revolutionary struggle for freedom and for socialism.” Communists must continuously struggle against both the right and “left” deviation with respect to the economic aspect of the labor movement. We must participate in and lead the economic struggle of the class waged in the unions, as an essential part of developing the movement of the class to take up the struggle for socialist revolution and its ultimate emancipation via communism.

Our last correction to Thesis #3 is to note that economism is also distinct from, though related to, syndicalism. Syndicalism is the belief that, for the working class to emancipate itself, it must focus exclusively on developing the economic struggle and the unions, until eventually there are enough organized forces to wage a general strike to abolish capitalism. Syndicalists do not uphold the necessity of working class political struggle and organization – especially the Communist Party – nor the necessity of the dictatorship of the proletariat under the leadership of the Party in a socialist society. Economists may or may not be syndicalists.17

Communists and the working class movement

Comrade Saoirse’s fourth thesis is:

Given that a) the Communist movement is the movement of the proletariat, b) unions are the most basic organization of the proletariat, c) unions alone cannot liberate the proletariat, we understand that there must be thorough, consistent, and deliberate participation of Communists in the labor movement for the express purpose of transforming trade-union consciousness into Communist consciousness, and growing the Communist movement.

Her fifth thesis is:

The growth and development of the unions and the union movement itself is not the goal of Communist activity in organized labor, but merely a by-product of the actual goal of building the Communist movement and developing Communist consciousness among the working class.”

She elaborates in “Further Discourse” on this point: “Are reform movements the goal of Communist activity? Only the most wicked right-opportunists would say as much! Our goal is nothing short of Communism!”

We wholeheartedly agree that communists must work within the unions, both to participate in and lead economic struggles, as well as to guide these organizations towards a point where they may “act consciously as focal points for organising the working class in the greater interests of its complete emancipation.”18 However, it is not true that the communist movement is the same as the movement of the proletariat. As capitalism develops and the working class comes into being, so does its movement. The working class movement existed before socialism (and Marxism) was developed and is not the creation of communists.19 As for the development of the communist movement, firstly, Marxism arises outside of the spontaneous working class movement.20 Lenin describes the history of development of and relation between the working class and socialism in A Retrograde Trend in Russian Social-Democracy:

At first socialism and the working-class movement existed separately in all the European countries. The workers struggled against the capitalists, they organised strikes and unions, while the socialists stood aside from the working-class movement, formulated doctrines criticising the contemporary capitalist, bourgeois system of society and demanding its replacement by another system, the higher, socialist system. The separation of the working-class movement and socialism gave rise to weakness and underdevelopment in each: the theories of the socialists, unfused with the workers’ struggle, remained nothing more than utopias, good wishes that had no effect on real life; the working-class movement remained petty, fragmented, and did not acquire political significance, was not enlightened by the advanced science of its time. For this reason we see in all European countries a constantly growing urge to fuse socialism with the working-class movement in a single Social-Democratic movement. When this fusion takes place the class struggle of the workers becomes the conscious struggle of the proletariat to emancipate itself from exploitation by the propertied classes, it is evolved into a higher form of the socialist workers’ movement—the independent working-class Social-Democratic party. By directing socialism towards a fusion with the working-class movement, Karl Marx and Frederick Engels did their greatest service: they created a revolutionary theory that explained the necessity for this fusion and gave socialists the task of organising the class struggle of the proletariat.21

We agree with what Lenin says here, that there is no Communist movement until communists fuse with the working class movement. Likewise, in The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels describe communists as:

The Communists, therefore, are on the one hand, practically, the most advanced and resolute section of the working-class parties of every country, that section which pushes forward all others; on the other hand, theoretically, they have over the great mass of the proletariat the advantage of clearly understanding the line of march, the conditions, and the ultimate general results of the proletarian movement.22

To now return to Comrade Saoirse’s theses: our ultimate goal or aim as communists is Communism, and our aim in capitalist society is to lead a proletarian revolution for the working class to seize political power. However, the necessary preconditions for achieving these aims are that communists must first join, develop, and become the leading section of the working class movement. To say that the only working class movement is a communist one can only lead to sectarianism. If communists in the US put this incorrect conclusion into practice and only engaged with workers and working class struggle that was already communist, they are liable to remain indefinitely marginal. This sort of logic, left unchecked, leads to all sorts of confused ideas. It can even allow people and groups to delude themselves into thinking that they alone are the real working class movement, since they have incorrectly equated the communist movement with the working class movement. In contrast, to avoid these sorts of sectarian pitfalls, we must unite with and lead the existing working class movement, which is decidedly not guided by communists at present in the US, and which never will be if we are purist and remain aloof from it.

It is true that the growth and development of the unions and the economic struggle is not the only goal of communist work in organized labor; we agree with Comrade Saoirse that this is the goal of trade unionists. However, since we must work to develop, strengthen, and lead the working class movement – by uniting with the relatively advanced workers in the movement – a significant task in front of us is to develop and strengthen the economic struggle and the union movement (by leading struggles, by propaganda, by political education for workers, etc). Thus, it is inaccurate to say that building the union movement is a byproduct of building the Communist movement and developing Communist consciousness amongst the working class. This formulation insinuates that the development of the union movement is not a necessary aspect of developing the Communist movement, and that the former would instead develop only as a side effect or result of the latter.

Rather, the Communist and union movements have a mutual effect on each other, where the further development of the union movement can provide grounds for the development of the Communist movement, and vice versa.

The role of unions in the economic struggle of the working class, and in the working class movement more broadly

As we stated above, unions are the most basic, broad, and elementary organizations of the working class. Unions initially developed, in every country, out of spontaneous actions by workers to fight against wage cuts, speed ups, and dangerous working conditions. The workers formed unions as they gained the basic consciousness that, to fight against these abuses by the capitalists, they were helpless as individuals in competition with each other and had to instead join together in collective resistance.

Comrade Saoirse’s second thesis is: “The primary function of unions is maintaining the value of workers’ labor-power.” Our interpretation of this statement is that the unions seek to maintain wages at or above the value of labor power for the working class. This is a more precise articulation, in that it accounts for the fact that the actual value of commodities needed to reproduce the average worker in a given society can vary drastically over time, due to a combination of technological developments and changes in the socially-defined scope of what’s “necessary” for reproduction beyond the minimum biological requirements.

This rephrasing also emphasizes the contradiction between the price form and the value form.23 For example, the value of labor power could well remain constant, but the price of labor power could fall for a variety of reasons (e.g. increased unemployment leading to greater competition among workers for fewer jobs, etc.). In this situation, the battle would not be over maintaining the value of labor power, which would not necessarily fall, but the price of this commodity in the face of an excess of supply over demand in the prevailing market conditions.24

Even given this refinement, there is a question as to what degree the unions in the present-day United States are able to fulfill this role. In a situation where only 11% of workers (6.9% if we limit to the private sector) are organized,25 it may well be the case that the existing unions’ influence is insufficient to have a significant impact on the price of labor power, even for their own members. On the other hand, in some instances we can see how the union struggles in some sectors of the economy even impact the wages of non-unionized workers in that same sector; e.g., Amazon and FedEx are loosely constrained to offer commensurate wages and benefits to their unorganized logistics warehouse workers as UPS does to its organized ones.26

What’s more, in the realm of the economic struggle, unions are not limited to fights around wages; there are also fights around working conditions. In a given economic struggle, higher wages will not necessarily be the primary demand: it may be for union recognition, collective bargaining rights, seniority rights, benefits, improved working conditions, more or fewer hours, an end to forced overtime, etc.

All this being said, while waging the economic struggle is the primary function of the unions, the unions need not and must not limit themselves just to waging the economic struggle. As Marx put it in the resolutions of the First International, “Apart from their original purposes, they must now learn to act deliberately as organising centres of the working class in the broad interest of its complete emancipation. They must aid every social and political movement tending in that direction.”27 We view this as an essential lesson of Marxism that communists must not disregard. We must not neglect or underemphasize the essential work of teaching the working class that its interests are not confined to wages and working conditions, and of transforming the unions to fight for the class’s complete emancipation. This task of Marxists in union work must be consciously incorporated into the strategy of boring from within the reactionary unions. This is why, while the recent union resolutions for a ceasefire in Gaza and for support of the Palestinians are modest,28 they are important steps forward in the working class becoming conscious of its interests and taking stands on issues besides its immediate economic situation.

Where should communists focus efforts?

The following points are discussed in “MCU and the Working-Class Movement,” but we will mention them again here, and clarify an imprecision in that document.

At present in the US, communists are weak, confused, and significantly divorced from the working class movement. As discussed earlier, our tasks thus include uniting with the working class movement, not to be passive participants in the movement but to provide it with communist leadership. However, the overall primary front of struggle for communists at present – both in general, and within the working class movement in particular – is the ideological one. The distinction drawn in “MCU and the Working-Class Movement” between theoretical/ideological work and practical work is imprecise. This is because within what could be called ideological work, there is both a theoretical and a practical component. On the one hand, there is the theoretical work of study, research, synthesizing knowledge, writing theoretical articles, etc. On the other hand, there are the various practical-organizational tasks associated with actually bringing this theory to the proletarian masses at various levels; waging ideological struggle within Marxist circles over what Marxism is, including by struggling against various forms of revisionism and opportunism; and developing communist organization quantitatively and qualitatively.

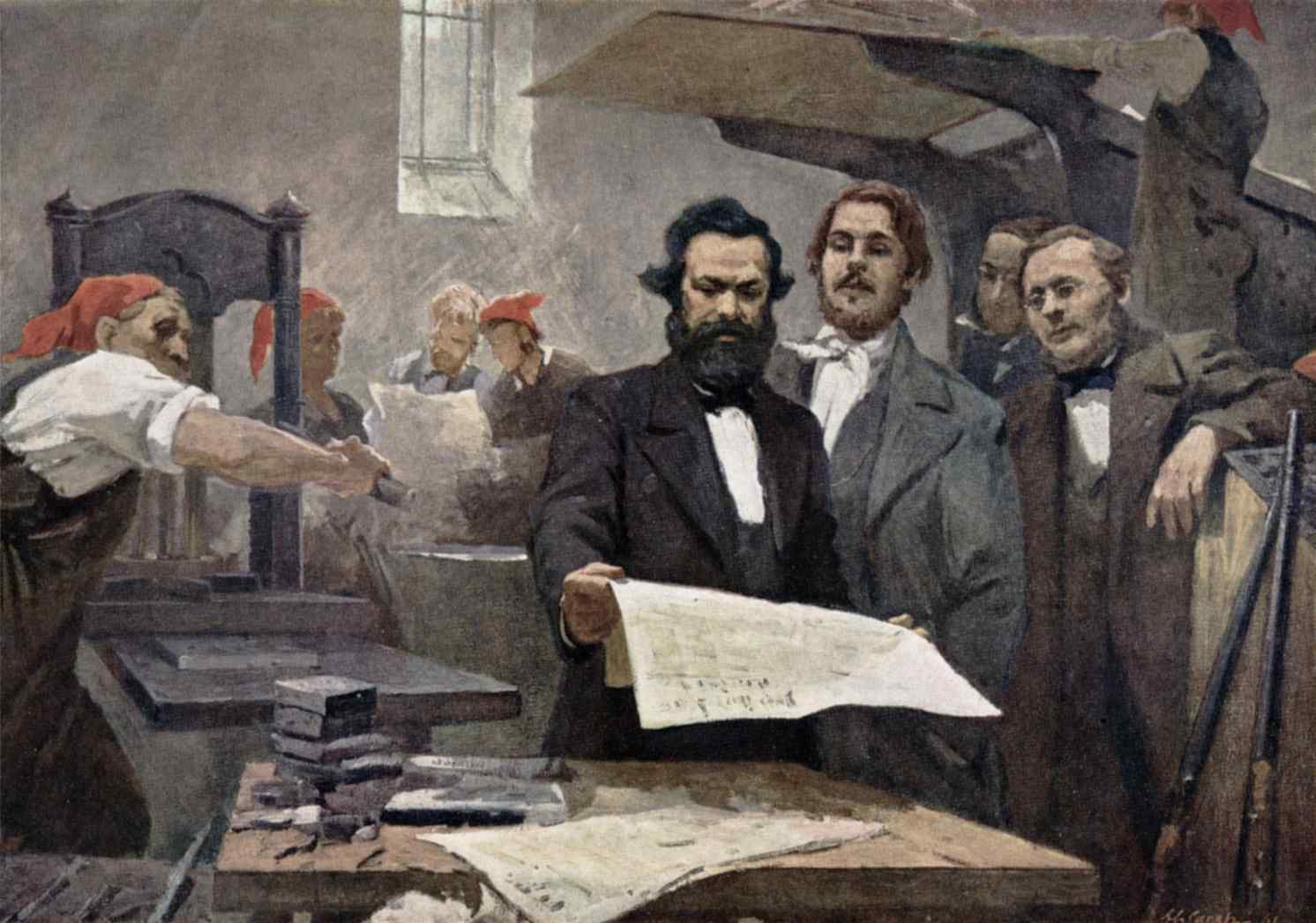

It is interesting, for instance, to look at the work Marx and Engels led in the Communist League and how,29 even while a revolutionary situation (i.e. 1848) was clearly on the horizon, what the League considered “action” (as opposed to “theory”) was first and foremost the action of propagating their program and newly adopted theoretical outlook amongst masses of working people. This included founding mass organizations of workers like the German Workers Educational Association and publishing a paper for the League. It is also worth recalling Lenin’s polemic in What is to be Done? against the idea that “action” means mainly “organizing demonstrations,” carrying out “drab, everyday” trade-union functions, or (worse yet) acts of terrorism, and his related opposition to the idea that the work of putting together an all-Russia Marxist paper was “armchair theorizing” or mere “paper work.” Instead, Lenin emphasized that the paper “is not only a collective propagandist and a collective agitator, it is also a collective organiser,” and that the only way for communists to participate as communists in those “practical activities” (which his critics glorified) is if they are organized to propagate Marxist theory generally and a Marxist understanding of the specific outrages that are the target of such “practical activities” in particular.30

In order to propagate Marxist theory and provide Marxist exposures of outrages in society, as well as to provide communist leadership to the working class movement, we must struggle to further develop communist consciousness ourselves and solidify our understanding of Marxism (which in our present day is Marxism-Leninism-Maoism). For example, we in MCU are glad to be taking part in this national debate on how communists should work in the labor unions, since basic unity on the correct strategy in the union struggles will allow us to make much more significant advances on this front with the limited forces we have now. However, the fact that, in the course of carrying out said debate, we immediately come up against such basic questions as how to define the “labor movement,” speaks to the theoretical shortcomings communists currently have which tend to prevent us from actually applying a correct Marxist line in practice. This state of affairs is not the fault of any one communist individual or group, but rather an outgrowth of the near-total degeneration of communist forces in the US since the 1940s, with only a brief, and still very confused, resurgence in the 60s and 70s. Of course, our orientation in theoretical study and writing must still be towards applying our resulting rational knowledge in practice, since we know this practice is ultimately of primary importance (that is, over theory) in actually transforming the material social reality we are a part of.31

Despite the various theoretical confusions and shortcomings of communists in the US, we should not delay in joining with and providing communist leadership to the working class movement.

Leadership entails not just leading various struggles, but also providing clarity on the way forward in these struggles and in the working class movement as a whole. In our practical work in the working class movement, we should prioritize practical ideological work (i.e. propagating Marxism and making Marxist exposures) over practical organizing work (e.g. organizing various economic campaigns on the shop, local, national level). Especially in the US, there is a very strong tendency amongst self-identified Marxists in the unions to emphasize practical organizing (“doing the real work on the ground,” “building shop floor militancy,” etc) over the task of raising class consciousness. However, our role as communists is not to be trade unionists, but to unite with the advanced workers (relative to the entire working class movement) and win them over to Marxism, while working with them to raise the level of the intermediate workers and win over the backwards.32 In order to do this, we must of course be engaged in practical organizing tasks, but these are secondary to our practical ideological tasks.33

Regarding the sections of the working class in which we should focus our practical work and where to get jobs to organize, we agree with Comrade Saoirse that we should focus on work amongst the industrial proletariat. This emphasis on concentrating our forces principally amongst the industrial proletariat is essential not only at our current juncture, where communist forces are few and weak in the US, but it will continue to be the essential section of the working class for communists to base ourselves amongst. While we must conduct more investigation as to which specific sections of the working class constitute the relatively advanced in our current moment, the vanguard section of the working class – the most organized, disciplined, and ideologically clear – will almost surely come from the large-scale industrial proletariat given how its conditions of existence have historically lead to this subset of workers being more open to Marxism and having a higher level of discipline and organization.34 The industrial proletariat is also the section of the working class that will be critical in paralyzing the essential sectors of the economy in a revolutionary crisis to facilitate the seizure of working class political power. The industrial proletariat is also not a class apart from the proletariat as Comrade Saoirse says; it is a section of the proletariat.

Given the above, how, and with what aims, should communists work in the unions?

In our work in the unions, we should unite with the existing working class movement, develop close links with the relatively advanced workers, gain experience in leading economic struggles, develop study circles for workers to teach them Marxism, and develop ourselves as agitators and propagandists in order to propagate Marxism. Although at present our work in the working class movement will be in its economic struggles since these are the main struggles the class is waging in the US right now, we must maintain the longer-term view that our role is to guide the working class movement to develop out of its political degeneration. Thus, we must not limit our exposures to those concerning economic issues and must struggle resolutely against economist deviations which are bound to crop up.

Furthermore, as stated in “MCU and the Working Class Movement,” “[t]he fact that theoretical and ideological tasks, at present, take precedence, does not in any way mean that practical work [in the economic sphere] should be abandoned.” However, we should engage in practical economic organizing work that does not take such an inordinate amount of time that we cannot focus on our key ideological tasks.

We now return to some of Comrade Saoirse’s points about the strategy of boring from within the reactionary unions. We have been studying the history of the CPUSA gaining considerable influence in the unions and raising class consciousness in the 1920s and 1930s, and this history confirms the correctness of boring from within the reactionary US unions.35

The basic idea of boring from within is what Lenin laid out in Left-Wing Communism: the unions, including positions of union leadership, are in fact sites of struggle as much as bourgeois parliament.36 There is in general a need for communists to participate in reactionary unions and contest their leadership, not simply to throw up our hands and say, ‘well, they’re reactionary, so the only principled participation with regards to them is to stand apart from them and call for their destruction.’ This is even more infantile than saying the same about bourgeois parliament, because of the importance of unions as the most broad and basic organizations of the working class. Throwing our hands up leaves the leadership of these unions to reactionaries and social-opportunists.

However, communists should also not fetishize taking leadership of the unions. This is not an end in itself, and right now our efforts certainly cannot be aimed at immediately driving out the reactionaries. Rather, we are partaking in whatever struggles exist in the unions against the employers and these reactionaries in leadership, to solidify ourselves and link up with advanced workers. It’s very possible, in any given union in which we are now engaging, that we will get a lot out of our participation and leadership within it but never actually succeed in turning that particular union red.

Comrade Saoirse’s sixth thesis is:

The growth of the Communist movement out of the labor movement and the transformation of trade-union consciousness into Communist consciousness will be achieved through political exposures and organized mass struggle against both the bosses and the reactionary union bureaucracy. Communists must make alliances with the rank-and-file of each union explicitly against both of these foes, and must not engage in the factional struggles between this and that clique of our class enemies to the detriment of the workers.

We have already noted why it is incorrect to equate the labor movement with the union movement, why communist theory and the working class movement arise and develop separately (until such a time as communists bring about a fusion of the two through their conscious activity), and what is needed for the development of a communist movement worth its name (that is, for communists to be the practical and theoretical vanguard of the working class movement).

Comrade Saoirse correctly notes that “the transformation of trade-union consciousness into Communist consciousness will be achieved through political exposures and organized mass struggle against both the bosses and the reactionary union bureaucracy.”

It is important to note that Communist consciousness, as we noted above, cannot arise just because of these factors, but requires the training of the working class in Marxism and political exposure of all major social issues of the day. We would also add that, in addition to struggle against the employers and reactionary union bureaucracy, there must be exposures of and struggle against the social-opportunist forces within the unions who are leading both the relatively advanced workers and the self-identified Marxists who have gone into the union movement down dead ends exemplified by the trends of “class struggle unionism” and the “rank-and-file strategy.”37 At times they will be more significant obstacles to our work in the working class movement than the reactionary leadership – particularly in the theoretical struggle to clarify Marxism to the workers and various Marxists.

As communists, we must not limit ourselves only to making alliances with the rank-and-file against these foes. At certain times, it will make sense to form tactical alliances with certain sections of leadership to exploit contradictions amongst them, and it would be a left deviation to foreclose fully upon this possibility. The CPUSA, in its active and non-revisionist period, allied with certain sections of progressive and opportunist union leadership to oppose the bourgeoisie and the most reactionary AFL leadership and advance the working class movement. Of course, it was not always possible to do so on terms consistent with the general class interests of the proletariat. Oftentimes opportunist social democrats were some of the biggest supporters of the reactionary AFL leadership headed by Gompers and Green, just as a section of DSA and PSL members are some of the biggest supporters of the reactionary IBT General President Sean O’Brien today. But the CPUSA’s alliances with non-communist forces were key to the advances they made in the 1920s and 1930s.38 Some key examples include John Fitzpatrick and his progressive allies in the Chicago Federation of Labor, who participated in a strong (though short-lived) Farmer-Labor Party movement in the early 1920s, and John Lewis, President of the UMWA, who would be a leading element in splitting the CIO from the AFL and even played a significant role in resisting, even for a relatively short period of time, cooptation of the industrial unionization movement by Roosevelt and his liberal bourgeois allies in the state and the AFL.39

Forming such alliances does not mean we cease criticism or struggle against opportunism or reactionary union leaders. Nor are these alliances contingent on forgoing our political independence, within the unions and working class movement more broadly. The united front is, of necessity, a front of struggle.

Working within the reactionary unions, independent unions, and organizing the unorganized

Comrade Saoirse raises a number of points about the relation between working within reactionary unions, forming independent unions, and organizing the unorganized.

Her eleventh thesis reads:

Whether we believe it best to work continuously within the reactionary unions or to form our own red unions is still a matter of debate until our Congress. Regardless, we must acknowledge that either way, it will be necessary to work within the reactionary unions at least for a period of time, and, splitting with reactionary unions will be necessary at least in extreme circumstances.

A major reason to bore from within the reactionary unions is so that we can drag the reactionary union leadership kicking and screaming to organize the unorganized, especially the unorganized industrial proletariat. This is a particularly important consideration today in the US, where union density is at 6.9% among private sector workers. In these circumstances, boring from within the existing unions with their existing membership alone (even if done well) will not put us in a position to advance the working class movement very far.

Therefore, we don’t fully agree with the following statement in Comrade Saorise’s “Further Discourse”: “Why would we go into an unorganized workplace, within an unorganized industry, and subject ourselves to the redbaiting, class collaborationism, and corruption of the existing reactionary unions? This, too, would be folly!”

Ideally, by boring from within these unions effectively, proletarian forces will have blunted some of the most horrible “redbaiting, class collaborationism, and corruption” pervading the union leadership and have gained some degree of political influence within the unions in question. Once this influence is established, it makes it much easier for new sections of previously unorganized workers to be organized into the union on terms that are not only favorable for these workers, but which also help to advance the class struggle more broadly. In particular, if we can organize relatively advanced workers into the existing reactionary unions, it will aid in our efforts to build left-wing opposition in those unions, further bore from within, organize more sections of the unorganized, etc.

To be sure, there will be plenty of situations (especially once the working class movement here has grown stronger) where it makes the most sense to form independent unions in a given workplace or industrial sector. It also will be necessary in some cases to split a section of organized workers from an existing reactionary union. However, we believe that in many independent organizing efforts, the correct strategic orientation will still be to eventually affiliate with one of the larger unions still under dominantly-bourgeois leadership.

It can be helpful to again look at the example of work the CPUSA did in the 1920s and 30s. The task of US communists in this period was not solely to support and create independent unions. Working with (or creating) independent unions included making a plan, from the outset, for affiliation with the existing larger unions;40 this was the case, for example, with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers and Amalgamated Food Workers. Affiliation, when carried out correctly, serves both to drive a wedge in the reactionary officialdom and likewise connects up the newly organized workers with the mass labor movement, giving workers a “far greater confidence and staying power.”41 Even though this strategy was promoted by the Comintern and taken up in principle by the TUUL, the TUUL often leaned too heavily into independent unionism, and put the task of planning for affiliation with AFL unions on the back burner. Still, these shortcomings in applying this line in no way detract from the overall correctness of the line.

Of course, the strategy of affiliation cannot be applied dogmatically. There are all sorts of factors to consider in order to determine the optimal course of affiliation of an independent union into an establishment one. For example, it would not generally make sense to affiliate when the union in question is seeing its members flee in droves, or when a mass expulsion campaign of communists and radicals is underway. We cannot simply hand over our organizations to the large reactionary unions; we have to, where possible, affiliate upon favorable terms.42 In addition, Foster emphasized that, while the terms of affiliation must not concede all leadership, they still cannot be so unrealistic as to totally prevent the possibility of affiliation.43 Historical experience demonstrates that short-sightedness on the part of the reactionary union leaders, their eagerness to expand and increase their dues pool, and the like, can help push things forward.44

All of this being said, the CPUSA’s work in the TUEL and TUUL was not without errors. In both formations they made both right and “left” errors. At times they dragged out affiliation with the AFL for too long, after it clearly didn’t make sense to continue; at other times they delayed affiliation when it made sense to act rapidly to affiliate.45This is far from a comprehensive summation of the lessons from this period; further study and analysis of this rich history are needed to inform our present work in the unions and the working class movement more broadly.

As to whether or not independent unions should be revolutionary ones, our view is that it does not make sense to push for the formation of independent red unions at present, given the low level of class consciousness of the working class. Even at the time of the TUUL, where there was a relatively higher level of militancy, class consciousness, and an existing Communist Party, it was premature for all TUUL unions to have a revolutionary line.46 There is a significant difference between establishing a revolutionary program for an organization of the militant minority in the unions and imposing such a program in a union that seeks to embrace all workers in a given workplace or industry at their present level of class consciousness and political development. We think that, in most situations for the foreseeable future, it will not make sense to establish explicitly revolutionary labor unions in this country.

On revolutionary caucuses

Comrade Saoirse’s eleventh thesis states, “We should make use of Revolutionary Worker’s Committees which operate semi-clandestinely for the purpose of pushing a red line in unions. Experimentation and regular summations are necessary for determining the best way to utilize these structures.”

While we are not exactly sure what Comrade Saoirse means by Revolutionary Workers’ Committees, we can share our own debate and discussion regarding the basis for creating explicitly revolutionary workplace mass organizations at present.

We will first note that while there is a need to keep certain organizational structures secret at times (such as an organizing committee being secret from management before going public), generally any workers’ organization in the unions should be broad and open, not clandestine or semi-clandestine.

In a country where bourgeois democracy is the prevailing form of class rule – and where a shift to fascist repression is not on the immediate horizon – it does not generally make sense for mass organizations to operate according to a policy of secrecy. Such a policy will isolate all but the most advanced workers from the broader mass of intermediate and backwards workers. There are of course, some exceptional circumstances (e.g. during a “Red Scare” or at a brutally repressive workplace).

It is not clear if Comrade Saoirse also means that communists should generally be secret or semi-secret about their politics, but we believe that hiding our politics in this manner will only make us more susceptible to coworkers’ suspicions and anti-communist ideas. If we are operating in a semi-clandestine caucus or being semi-secretive about being communists, we won’t be able to explain to coworkers (and show in practice) why communists aren’t weird and conspiratorial.

In MCU’s initial discussions around a communist line on work in the existing unions – before taking up systematic study on this question and before we had much practical experience in unions – we had an idea of remaining somewhat aloof from the existing union structures and building revolutionary caucuses (though what exactly this meant always remained fairly vague in our understanding at the time). We believed that this was the form of organization to develop on the shop floor, locally, and nationally.

However, we never attempted to build revolutionary caucuses as we quickly realized there is not a basis to do so at present. Given the low level of class consciousness amongst the working class in this country, there are very few workers who presently would see a reason to join an explicitly revolutionary caucus. To see developing revolutionary workers’ organizations within the unions as our primary task no matter the circumstances is a “left” deviation that will inevitably have a number of negative effects. The most common of which include isolating ourselves and revolutionary-minded workers isolated from the intermediate and backwards workers, as well as isolating us from the relatively advanced workers in a given workplace or union.47 Across the reactionary-dominated unions, even truly oppositional organizations struggling against reactionary leadership are few and far between.

Of course, if we meet coworkers who are interested and enthusiastic to learn more about communist politics, then we should seize on this, and have some systematic way to conduct studies, make exposures, and bring them into communist organizations as makes sense. But this must be done in tandem with collaboration on non-revolutionary struggles and organizations which the intermediate will join and support, through which we can raise the level of the intermediate. For example, we (the authors) joined Teamsters Mobilize, a grassroots workers’ organization within the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, in the midst of the UPS contract struggle in the summer of 2023. Through our involvement in this pre-existing group, we’ve had many opportunities to collaborate with fellow Teamsters members to find various ways of exposing the class-collaborationist labor misleaders at the helm of the US union movement right now. While this does not, in and of itself, constitute a revolutionary political line, it is a strategy that can potentially unite a large swath of workers currently within the Teamsters who are critical of both the IBT executive leadership as well as the opportunist leaders of Teamsters for a Democratic Union.To be clear, we by no means intend to imply that there will never be a basis for revolutionary organizations within unions, but that we must not be hasty to form these kinds of organizations before there is actually a material basis to do so.

We want to emphasize that communists participating in or leading a mass organization that is not explicitly a revolutionary one does not and must not preclude us from providing communist leadership and being open about our views. Of course, we should not sloganeer; we should be discerning with how to raise various political questions with various workers; we should evaluate who to talk with more in depth about Marxism; and we should not prematurely push workers to join a communist organization. However, in general, we must not be afraid to put forward Marxist politics. Otherwise, if we hide our politics until some later date or say we are Marxists but dilute Marxism to trade unionism, we will be subordinating the need to raise class consciousness to developing the economic struggle.

In conclusion

As we noted in the beginning, we think Comrade Saoirse’s contributions are overall positive, and writing this response has pushed us to reevaluate our own thinking on a number of these questions. These kinds of exchanges are desperately needed. We look forward to reading any responses, questions, or criticisms. You can reach us by emailing MCU at maoistcommunistunion@riseup.net.

- One need only query the term “labor movement” on the Labor Notes website to get a sense for how pervasive this false equation has become – https://labornotes.org/search/node/labor%20movement. For instance, in their article for the publication Parker and Gruelle state the following: “Many leaders of the labor movement know that they need members in motion if they’re to win anything. But too many envision a mobilized labor movement as troops ready to respond to the commands of their officers.” Here the term “labor leader” is used synonymously with “union leader.” And: “One reason is the very conditions of global capitalism. Global competition means first and foremost that the labor movement must constantly spread. There is no security in organizing one workplace, one industry, or one company.” The authors conceptualize the development of the labor movement as a purely quantitative transformation of the economic struggle of the working class, in which more and more workers organize into unions. See: Mike Parker and Martha Gruelle, “Rank-and-File Power Is Essential to Rebuilding the Labor Movement,” Labor Notes, September 7 2022, https://labornotes.org/blogs/2022/09/rank-and-file-power-essential-rebuilding-labor-movement.

- Karl Marx, “Letter to Bolte,” November 23, 1871, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1871/letters/71_11_23.htm.

- Friedrich Engels, “Addendum to the Preface,” in The Peasant War in Germany, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1850/peasant-war-germany/ch0b.htm.

- In 1886, Marx wrote for the International Workingmen’s Association: “Trades’ Unions originally sprang up from the spontaneous attempts of workmen at removing or at least checking that competition, in order to conquer such terms of contract as might raise them at least above the condition of mere slaves. The immediate object of Trades’ Unions was therefore confined to everyday necessities, to experiences for the obstruction of the incessant encroachments of capital, in one word, to questions of wages and time of labour. This activity of the Trades’ Unions is not only legitimate, it is necessary. It cannot be dispensed with so long as the present system of production lasts. On the contrary, it must be generalised by the formation and the combination of Trades’ Unions throughout all countries.” Marx goes on to explain how the working class must use the unions to organize for its emancipation, which we discuss later on in this document in point #3. See: Marx, “Trades’ unions. Their past, present and future,” August 1866, https://www.marxists.org/history/international/iwma/documents/1866/instructions.htm#n06.

- “Letter to Bolte,” https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1871/letters/71_11_23.htm.

- While such manifestations of working class political struggle can constitute positive advancements in the labor movement generally, Lenin describes in What is to be Done? the manner in which the Economists obfuscate their discounting of the political struggle by limiting their conception thereof strictly to extensions of trade union demands: “Lending ‘the economic struggle itself a political character’ means, therefore, striving to secure satisfaction of these trade demands, the improvement of working conditions in each separate trade by means of ‘legislative and administrative measures’ … This is precisely what all workers’ trade unions do and always have done. Read the works of the soundly scientific (and “soundly” opportunist) Mr. and Mrs. Webb and you will see that the British trade unions long ago recognised, and have long been carrying out, the task of “lending the economic struggle itself a political character”; they have long been fighting for the right to strike, for the removal of all legal hindrances to the co-operative and trade union movements, for laws to protect women and children, for the improvement of labour conditions by means of health and factory legislation, etc.”

- For example, in 2019 dock workers at a Genoa, Italy port engaged in a political strike to block the loading of weapons bound for Saudi Arabia, weapons which the Saudi government was planning to use in its genocidal war on Yemen. In this strike, the workers were struggling not over wages, hours, and conditions, but over the role that their country was playing in supporting the war. While this was far from a political struggle of the whole Italian working class, it shows how advanced elements of the proletariat do take up political struggles which are disconnected from their immediate economic demands. See: Steve Sweeny, “Working-class internationalism: Italian dock workers block Saudi weapons ship,” People’s World, May 21 2019, https://www.peoplesworld.org/article/working-class-internationalism-italian-dock-workers-block-saudi-weapons-ship/.

- While the outbreak of the World War would later temporarily put a damper on the working class movement in Russia, the various crises in Russia which the war caused and exacerbated eventually led to a strong revival of the movement and its escalation to full-blown revolution a few short years later. See: Aleksandr Šljapnikov and Richard Chappell, On the Eve of 1917: Reminiscences from the Revolutionary Underground (London: Allison & Busby, 1982), 9-10.

- As Lenin noted in “Left-Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder, “How is the discipline of the proletariat’s revolutionary party maintained? How is it tested? How is it reinforced? First, by the class-consciousness of the proletarian vanguard and by its devotion to the revolution, by its tenacity, self-sacrifice and heroism. Second, by its ability to link up, maintain the closest contact, and—if you wish—merge, in certain measure, with the broadest masses of the working people—primarily with the proletariat, but also with the non–proletarian masses of working people. Third, by the correctness of the political leadership exercised by this vanguard, by the correctness of its political strategy and tactics, provided the broad masses have seen, from their own experience, that they are correct. Without these conditions, discipline in a revolutionary party really capable of being the party of the advanced class, whose mission it is to overthrow the bourgeoisie and transform the whole of society, cannot be achieved. Without these conditions, all attempts to establish discipline inevitably fall flat and end up in phrasemongering and clowning. On the other hand, these conditions cannot emerge at once. They are created only by prolonged effort and hard-won experience. Their creation is facilitated by a correct revolutionary theory, which, in its turn, is not a dogma, but assumes final shape only in close connection with the practical activity of a truly mass and truly revolutionary movement.”

- The Paris Commune is, of course, one such example of the temporary success of the proletarian revolution in the absence of a developed Communist Party. However, its extremely brief existence (just 72 days) and its inability to achieve country-wide victory in France speak to the necessity of an organized and disciplined Communist Party leading the proletarian revolution in order for it to fully succeed and hold on to its victory in the face of the inevitable counter-revolutionary efforts of the bourgeoisie.

- VI Lenin. 1975. Lenin Collected Works. Vol. 18. Pages 83-90. Progress Publishers. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1912/may/31.htm

- Ibid. For more of Lenin’s writing on this topic, please see “Draft and Explanation of a Programme for the Social-Democratic Party” (1895): https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1895/misc/x01.htm and “1907 Draft Resolutions for the Fifth Congress of the RSDLP”: https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1907/5thdraft/index.htm

- Sergei Ivanovich Gusev was a Bolshevik who served as Secretary of the Bureau Majority Committees and the St. Petersburg Party Committee from 1904-1905, and in 1905 was part of the Odessa Bolshevik Committee. In his letter to Gusev dated October 13, 1905, Lenin disagrees with a resolution of the Odessa Committee on the trade union struggle which says that once communists are preparing for an armed uprising, “the task of leading the trade union struggle of the proletariat inevitably recedes into the background.” In response, Lenin emphasized that communists must never belittle the importance of providing leadership to the trade union struggle, which is “one of the constant forms of the whole workers’ movement, one always needed under capitalism and essential at all times.” Although Lenin is discussing the trade union struggle, we include this because in this letter and in What is to be Done, Lenin uses “trade union struggle” (or “organized labor struggle”) and “economic struggle” interchangeably. We assume this is because the economic struggle is by and large waged by the unions, and waging this struggle is their primary function. However, we prefer not to equate these terms as the union struggle is not reducible to the economic struggle, insofar as unions can and have taken up larger political struggles. See: V.I. Lenin, “To: S. I. GUSEV,” October 13 1095, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1905/oct/13sig.htm

- Lenin, What is to be Done?, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/

- See Lenin’s What is to be Done? Chapter 1 on the importance of theoretical struggle.

- The RCP has since degenerated into a cultish formation, but was the most significant Maoist organization in US history in terms of size and its influence on the working class movement. The Revolutionary Union (or RU, the direct predecessor organization to the RCP) and then RCP initially saw the importance of providing leadership to the working class’s economic struggles, and it was expected that members would take up proletarian jobs and organize in them. However, they pulled all cadre out of workplace organizing by 1978, on the grounds that participating in economic struggles is economist.

- See Foster’s 1912 pamphlet for the Syndicalist League of North America: William Z. Foster and Earl C. Ford, “Syndicalism,” October 15 1912, https://www.marxists.org/archive/foster/1912/syndicalism/1-goal.html; Foster later repudiated syndicalism once he became a communist. See: William Z. Foster, From Bryan to Stalin (New York, NY: International Publishers, 1937), https://bannedthought.net/USA/CPUSA/WZFoster/WZFoster-FromBryanToStalin-1937-OCR-sm1.pdf.

- “Resolution of the I.W.A. on Trade Unions,” Geneva, 1866, https://www.marxists.org/history/international/iwma/documents/1866/instructions.htm#n06.

- Lenin says of the relation between the Communist Party and the working class: “The Party’s activity must consist in promoting the workers’ class struggle. The Party’s task is not to concoct some fashionable means of helping the workers, but to join up with the workers’ movement, to bring light into it, to assist the workers in the struggle they themselves have already begun to wage. The Party’s task is to uphold the interests of the workers and to represent those of the entire working-class movement.” See: Lenin, “Draft and Explanation of Programme for the Social-Democratic Party,” https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1895/misc/x01.htm.

- Lenin explains in Chapter 2 of What is to be Done? why it is not possible for trade-union consciousness to spontaneously transform into Communist consciousness. Communist consciousness comes from without, or outside, of the spontaneous working class movement, and must be brought to that movement by communists.

- V. I. Lenin, “A Retrograde Trend in Russian Social-Democracy”, written at the end of 1899 and first published in 1924 in the magazine Proletarskaya Revolyutsiya (Proletarian Revolution), https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1899/dec/trend.htm

- Marx and Engels, “Proletarians and Communists,” in The Communist Manifesto, https://www.marxists.org/admin/books/manifesto/Manifesto.pdf. A further discussion of this quote and our organization’s previous misunderstandings of our tasks as communists can be found in the document “MCU and the Working-Class Movement.”

- As Marx noted in Capital: Volume 1, “The possibility, therefore, of a quantitative incongruity between price and magnitude of value, i.e. the possibility that the price may diverge from the magnitude of value, is inherent in the price-form itself. This is not a defect, but, on the contrary, it makes this form the adequate one for a mode of production whose laws can only assert themselves as blindly operating averages between constant irregularities.” Karl Marx, Capital: Volume 1, Vintage Books Edition, August 1977, translation by Ben Fowkes, 1976, page 196.

- The inverse condition can also arise, in which due to the increase in labor productivity, the value of labor power has fallen significantly, because the socially necessary labor time to produce various means of consumption significantly decreased. In this situation unions would not generally fight against the increases in labor productivity that lead to decrease in the value of labor power, but rather fight against the wage cuts (in real or nominal terms depending on the dynamics in the given currency) which aim to drive down the price of labor power to or below the value of labor power.

- Heidi Shierholz, et al., “Workers want unions, but the latest data point to obstacles in their path,” Economic Policy Institute. January 23 2024, https://www.epi.org/publication/union-membership-data/.

- Max Garland, “UPS, Teamsters deal could ramp up wage pressure for logistics firms,” Supply Chain Dive, September 13 2023, https://www.supplychaindive.com/news/ups-teamsters-contract-competitors-wage-pressure-fedex/692878/.

- “Resolution of the I.W.A. on Trade Unions,” https://www.marxists.org/history/international/iwma/documents/1866/instructions.htm#n06.

- See the Labor for Palestine website, which posts all Palestine-related US union actions and resolutions.

- The Communist League was the very first organization more or less united around a Marxist program (in the form of the Communist Manifesto). It was a secret propaganda society mostly composed of German journeymen artisans scattered throughout major cities in Europe, who had previously (as the “League of the Just”) taken up a variety of utopian communist views, until Marx and Engels became acquainted with them and waged a struggle to transform their outlook. To learn more about the League, see Engels’ short history: Engels, “On The History of the Communist League,” Sozialdemokrat, November 12-26 1885, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/communist-league/1885hist.htm; For an a fairly comprehensive account of their activity in the League, despite being written by an academic Trotskyist, see the first several chapters: August H. Nimtz Jr., Marx and Engels: Their Contribution to the Democratic Breakthrough (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2000).

- See the fifth chapter of What is to be Done: https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/v.htm.

- “If we have a correct theory but merely prate about it, pigeonhole it and do not put it into practice, then that theory, however good, is of no significance. Knowledge begins with practice, and theoretical knowledge is acquired through practice and must then return to practice.” Mao Zedong, On Practice, July 1937, https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-1/mswv1_16.htm.

- “The masses in any given place are generally composed of three parts, the relatively active, the intermediate and the relatively backward. The leaders must therefore be skilled in uniting the small number of active elements around the leadership and must rely on them to raise the level of the intermediate elements and to win over the backward elements.” See: Mao Zedong, “Some Questions Concerning Methods of Leadership,” June 1, 1943, http://www.marx2mao.com/Mao/QCML43.html.

- In What is to be Done? Lenin argues against the Economists’ overemphasis on making exposures about the economic struggle: “Social-Democracy represents the working class, not in its relation to a given group of employers alone, but in its relation to all classes of modern society and to the state as an organised political force. Hence, it follows that not only must Social-Democrats not confine themselves exclusively to the economic struggle, but that they must not allow the organisation of economic exposures to become the predominant part of their activities. We must take up actively the political education of the working class and the development of its political consciousness.”

- Lenin notes in the Lecture on the 1905 Revolution that the metal workers came forward as the advanced section of the industrial proletariat in the 1905 revolution and were “the best paid, the most class-conscious and best educated proletarians”, in contrast to the textile workers, who were the worst paid and most backward workers. We must, when evaluating where to concentrate forces, unite with the relatively advanced; our criteria cannot be to go principally amongst the workers with the lowest wages and worst working conditions (or the “lowest and deepest” sections of the working class) and assume these conditions automatically lead to higher class consciousness. However, it is worth noting the differences in the present-day US and Russia in Lenin’s time, given the formation of the labor aristocracy. The correlation between the best paid and most educated workers being the most class conscious does not hold for us to the extent that it did in Russia in Lenin’s time or that it had historically in various places.

- We must not discard the rich experiences of the class struggle in the Russian and Chinese revolutions on account of the fact that capitalism was eventually restored in both countries. Likewise, we cannot discard the advances made in the US working class movement as a result of communists boring from within the existing unions on account of the eventual consolidation of the CPUSA to revisionism by the late 1930s/early 1940s.

- See also the work done by the Chinese Communist Party within mass organizations, including unions, dominated by reactionaries (such as “yellow” unions controlled by the Guomindang) in the period of underground Party work in Shanghai before liberation. See: Communist Party of Australia (Marxist-Leninst), “Underground Party Work in Shanghai Before Liberation: A talk to a visiting group of CPA (M-L) members, December 1978,” August 2021, 21, https://www.cpaml.org/web/uploads2/AC+2021+Autumn.pdf.

- Comprehensive criticisms of these trends lie beyond the scope of what we can cover in this document. Within MCU, some comrades are currently working to produce more detailed written analyses of the ideas cited, along with explanations of why they are essentially bourgeois in character.

- The need for alliances with unreliable and wavering allies is an essential lesson of Marxism. As Lenin noted, “Only those who are not sure of themselves can fear to enter into temporary alliances even with unreliable people; not a single political party could exist without such alliances.” What is to be Done?, Chapter 1.

- See: David Milton, Politics of US Labor: From the Great Depression to New Deal (New York, NY: Monthly Review, 1982).

- “But wherever we form such new unions, whether because there are no A.F. of L. unions in the field or because those that may exist are absolutely decrepit, we must from the outset follow a program for the affiliation of these unions to the A.F. of L.” See: William Z. Foster, “Organize the Unorganized,” 1926, https://www.marxists.org/archive/foster/1926/organize-unorganized/index.htm.

- Ibid.

- As Foster put it, “We must fight for affiliation to the A.F. of L. unions, but we also must fight for honest and militant leadership, and mass industrial organization. Our growing left wing leaders must be provided a place to function in the unions, and above all, at this stage, we must retain the initiative in carrying on the great work of organizing the unorganized” (Ibid.)

- “Our greatest danger comes from a dual union tendency…This bases itself upon various illusions and wrong policies, such as… the presentation of impossible programs as the basis of amalgamation or affiliation…” (Ibid.) While the dual unionist tendency was the greatest danger at the time Foster wrote this document, opportunist tailing of reactionary union leadership is a much greater danger in the US today. That being said, “left” errors are still a widespread problem.

- “When per-capita-tax-hungry trade union officials see a fat independent union that wants to affiliate to their organization, they are much inclined to look upon it with some degree of friendliness and tolerance…” (Ibid.)