Renato Flores argues for self-determination and reparations for Black Americans as a key part of the revolutionary struggle in the USA. Reading: Robert Fish.

I

The uniqueness of the Black condition in the United States is hard to understand for anyone foreign to the Americas. Its complexity is often lost in semantic distinctions on whether Black Americans are a Nation or not. A typical first avenue to assess Nationhood is to mechanistically apply Stalin’s checklist: “common language, territory, economic life, and psychological make-up manifested in a common culture.”1 When this is applied to the Black nation, the obvious question becomes: where is the territory?

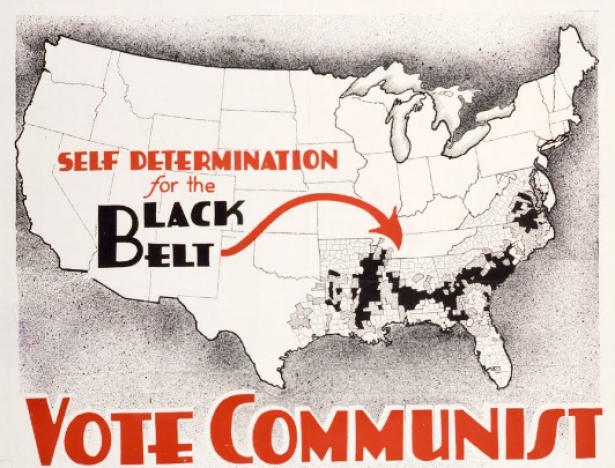

A dismissive answer would be to say that there is no land because population migration has rendered the Black Belt thesis obsolete. This answer is not only insufficient, but it is also hardly new: it has been leveled at the Black liberation movement since its inception in different shapes. Harry Haywood, the CPUSA’s leading theoretician on the Black Nation repeatedly answered this critique in the decades between the 20s to the 60s.2 As he presciently pointed out, migratory fluxes and the passage of time had done nothing to integrate black people. Looking from the era of Trump and mass incarceration, it is clear that this point still holds: Black oppression morphs in shape, but it never disappears.

An alternative answer is the Black Belt still exists in the shape of the 60-70 counties that still have a Black population of over 50% and their surroundings. This answer is poisoned, not only because there is a limited geographical continuity between these counties, especially those outside the Mississippi basin and the plantation belt in the South, but because it implicitly accepts the settler division of this continent. It also doesn’t outline how land claims from the Black Nation are compatible with Indigenous claims. Even worse, mere accounting of people could very well be leveraged against American Indian struggles to deny their validity when they occur in territory where settlers are the majority.

Furthermore, even if one accepts that the Black Nation has its territory in the Southern states, it is hard to outline a path to self-determination while this land is held by an intensely racist ruling class. This is barely a new objection: Cyril Briggs, who pioneered the idea of a Black Nation on North American land chose the far West for his Nation to avoid this problem. The boundaries of the Black Nation were never clearly outlined by Haywood and the CPUSA, knowing that even if a black nation-state was formed, it could end up landlocked by Jim Crow states and isolated. The CPUSA insisted on the black belt hypothesis despite its impracticality because it was necessary to check off land in Stalin’s checklist. The right to a separate state requires land, which complicated self-determination. To remain faithful to the Black Belt thesis required spending significant time addressing geographical questions.

The answer to this antinomy is to move past land. One cannot fully grasp the concept of a nation materially: the persistence of Black nationalism despite internal migration means that the “idea” of a Nation is more resilient than land. Benedict Anderson defines a nation as a socially constructed community, imagined by the people who perceive themselves to be part of the group. In this sense, it is hard to deny that Blacks in the United States constitute themselves as an “imagined community”. Slogans of “buy black” or “black capitalism”, as well as black separatist groups such as the Nation of Islam are very alive today, and they speak more to the Black masses than socialists do. Those who see in them petit-bourgeois deviations are behaving like their counterparts a hundred years ago, which were hit by the realities of Marcus Garvey’s “Back to Africa” mass-movement. Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association was able to temporally attract over a million black people while communists struggled to recruit blacks at all. By looking at its aftermath, Harry Haywood acknowledged the mistakes of the communist movement and formulated the first comprehensive call for self-determination in the Black Belt.3

So what can we say about the Black nation today? And what is the minimum socialist program for Black self-determination? To begin to understand this, we must remember two things. First, that the United States was founded on (white) race solidarity, and by default excluded black self-determination. Second, that the debt of “forty acres and a mule” remains unpaid, causing a wide economic disparity between Black wealth and White wealth. Both of these problems are discussed today, but never together. Trying to answer one at a time is insufficient; we need both economic and racial justice or will end up getting neither.

II

Anti-blackness is embedded in the DNA of the United States. The exclusion of black people from the community of whiteness offers fertile ground for a Black “imagined community”. Unlike layers of Asians and Latinos, Blacks will never have the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness in the United States. That would render the whole category of whiteness obsolete. Racial solidarity, the main stabilizer of class struggle, would disappear. The persistence of whiteness explains the persistence of Black nationalism.

The way race is constructed in the United States has few parallels, but they exist. In Traces of History, Patrick Wolfe elaborates on the founding of the United States, drawing similarities between the use of antisemitism to forge nations in Europe in the early 1900s, and the use of anti-blackness to forge race solidarity in the US. The question of European Jewry was tragically resolved through the horrors of the Shoah and the ethnic cleansing of Palestine to establish the ethnostate of Israel. Following Wolfe, we can look at the debates around the Jews in the 1900s to find ways to answer the Black question.

In the early 1900s, the largest Jewish socialist organization was the Bund, located in Eastern Europe and comprising tens of thousands of Jewish workers willing to fight for their liberation.4 The Bund called for Jewish self-determination, but in a different shape from that associated with the Bolsheviks. Its prime theorist, Vladimir Medem, drew inspiration from the Austromarxist school of Karl Renner and Otto Bauer. Medem demanded Jewish “national and cultural” autonomy, with separate schools to preserve Jewish culture. His brand of nationalism was of “national neutrality”, and opposed both preventing and stimulating assimilation. He just refused to make any predictions on the future of Jews.

Otto Bauer’s writings on the national question and self-determination are more remembered today by Lenin’s polemics than on their own right. Lenin was correct to criticize Bauer for denying territorial self-determination to nations within the Austro-Hungarian empire, and restricting them to “national cultural autonomy”. But by throwing away the baby with the bathwater, a different definition of self-determination and approach to nationhood was damned to obscurity. Bauer’s historicist definition of a nation as “a community with a common history and a common destiny” remains underappreciated in the Marxist tradition, even if it has influenced people like Benedict Anderson.5 Medem drew from the Austromarxist school even if Bauer denied nationhood to the Jews on the grounds that they lacked a common destiny. By limiting his look to the Western European Jews, Bauer failed to see the power of his approach where it was adopted.

The Bolsheviks also failed to capture the intricacies of the Jewish nation. Lenin framed the Jews as something more akin to a caste than a nation. Stalin dedicated an entire chapter of his National Question to polemicize against the Bund and the Jewish nation. By contrasting the cultural autonomy demands of the Bund to the struggles of Poles and Finnish for territorial self-determination, Stalin found the Bund’s demands as insufficient under Tsarist authoritarianism and superfluous under democracy. He also claimed that Jews were not a nation because “there is no large and stable stratum connected with the land, which would naturally rivet the nation together, serving not only as its framework but also as a ‘national market.” Both Lenin and Stalin saw assimilation as the only solution and shut the doors on Medem’s middle way. This meant that even if the Bund started its history closer to the Bolsheviks, they were eventually repelled towards the Mensheviks who accepted their nationalist vision.

In the aftermath of the October Revolution, the Bund would undergo several splits and realignments. Their program for Jewish self-determination never saw full and consistent implementation. In a cruel irony, both Bolsheviks and Austromarxists were proven wrong by the Jewish version of Garvey’s return to Africa: Zionism. The return to a mythical Jewish land was able to take hold among sections of Eastern European Jews, showing that they were never fully integrated. Zionism not only matched the mass appeal of Garvey, the support of Western imperialism made it achievable. When confronted with this serious ideological rival, the Bolsheviks realized their mistake and attempted to provide a “Jewish autonomous oblast,” giving a land basis to Jewish self-determination within the USSR. But that was a large failure: at its peak, only fifty thousand Jews moved to the oblast in Eastern Siberia. When offered second-rate Zionism, why not choose the original?

III

If we read Stalin’s original criticism of the Bund, we can find many parallels to present critiques of Black nationalism. Applying his rigid framework to black people can lead us to the absurd conclusion that the Black nation, and the impossibility of racial integration in the United States, is contingent on the continued existence of a small number of sharecroppers connected to the land. Haywood was too faithful to his party to abandon the narrow confines of Stalin’s definition of nation and adopt a different one. Thus, he was forced to repeatedly argue for the persistence of sharecropping rather than abandon the Black nation. His opponents never abandoned the same framework, and the real debate became obscured by the interpretation of geographical statistics.

We must recognize that this is an absurd either-or. We can try to rescue the idea of “national personal autonomy” as a way of granting self-determination when the land basis is not sufficiently solid, and using it as a way to “organize nations not in territorial bodies but in simple association of persons”. This provides a working program for Black self-determination which avoids the question of the land. Indeed, self-determination means nothing without the right to separate, and the right to organize blacks separately has been demanded by many revolutionaries throughout history. This includes someone like Martin Luther King, who said that “separation may serve as a temporary way-station to the ultimate goal of integration” because integration now meant that black people were integrated without power.6

Socialists should not be afraid of this: Black Nationalist associations such as the Black Panther Party or the League of Revolutionary Black Workers have been amongst the most revolutionary forces of the United States. A reason they were so successful was their ability to organize separately in their initial stages, and reach out to other movements on their own terms. But it is essential to remember that separation is being demanded by those communities, and not enforced. Separation can very well be used to enforce racial injustice as shown by the use of “separate but equal” schools.7

However, self-determination alone does not address the wealth disparity between races. Experiments in black self-determination like those being conducted by the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement in Jackson, Mississippi are bound to fail due to economic constraints. Black communities lack the wealth necessary to jump-start their own structures. This is the second pillar that holds up the existence of the Negro nation: the debt owed from the legacy of slavery. When the shadow of the plantation enters, the analogy between Blacks and European Jews breaks down, and the question of reparations becomes central.

IV

The most honest case against reparations is that of Adolph Reed.8 Reed never denies that the legacy of slavery has caused Black people to be at a significant economic disadvantage. However, he denies that the demand for reparations has progressive potential, and attributes it to petit-bourgeois nationalism (sound familiar?), where the middle classes attempt to rebuild a destroyed black psyche through back-room deals, in place of mass organizing.

Reed fails to see the potential for reparations to actually coalesce in a mass revolutionary movement. But fighting white supremacy need not begin from a revolutionary point. The original demands of the Montgomery bus boycott of the 60s were as mild as first-come, first-served seating, and did not even ask for desegregated buses. But anti-racism becomes a genuinely revolutionary movement by necessity if it is to reach its endpoint. We only have to observe MLK’s slow transformation to anti-capitalism. Every revolutionary movement in the history of this country has been led by black people and anti-racist organizing, be it the Reconstruction period after the Civil War, the strikes leading to the formation of the AFL-CIO, the second Reconstruction of Civil Rights or the Black Panther Party. History tells us that any path to a radical transformation of this country must go through anti-racist, anti-imperialist organizing or it is bound to stop halfway before reaching its goals.

Contrast reparations with Medicare for all. Medicare for all has the potential to immediately transform the lives of millions of people for the better. But Medicare for all does not fundamentally challenge capitalism. Sanders regularly points to Western Europe and other “industrialized” countries as examples that universal healthcare is possible (Cuba is a notable example he never mentions). As he accidentally shows, it is a demand that is perfectly possible to accommodate within the realms of capitalist societies. Settler-colonial states such as Canada and Australia provide universal access to healthcare for the “community of the free”. These countries are no less settler-colonial if they provide their settler-citizens with healthcare. The dispossession of indigenous people continues unabated, and Australia’s notoriously racist immigrant policy still holds. If this isn’t the definition of trade-unionist, economist demands then what is?

Decommodification of essential commodities is just ordinary Keynesianism: a way for capitalism to manage the inherent contradiction between laissez-faire economics and the existence of the hopeless poor.9 As Keynes and other economists faced down the Great Depression, the consensus became that state would mitigate the worst excesses of capitalism to save “the thin crust of civilization”. They would create poverty with dignity, incorporating the rabble into civil society by using government programs to provide them with their basic needs. The programs of the New Deal, and the creation of the post-war European welfare system are surely the largest bribes ever given to the working class, with the bill paid by the Global South. Guillotines were avoided, Keynesianism stabilized capitalism for over three decades. The proto-revolutionary proletarian rabble was turned into the social-democratic industrialized “middle” class, one that had gained an interest in preserving the system.

In 2019, neoliberalism has recreated on a massive scale the figure of the hopeless poor. Bernie and other progressives face the Long Recession with measures like Medicare for all and $15/hour minimum wage. “Democratic socialism” is the new word, twisted and redefined to mean anything. While this term means many different things for many people, the underlying ideal for Sanders is a system where we can manage the contradictions of capitalism and give it a human face through state intervention. Sanders tries to attract Trump voters by making class-based demands around which to unite the “99%”. Many socialists are trying to take advantage of Sanders’ cross-party appeal to revitalize the forces of revolutionary socialism. But as Lenin recognized, workers will not simply become revolutionaries by fighting for economist demands. Focusing on Medicare for All fails to outline a vision for a new society, and winning it could mean instead that sections of workers become disinterested in further challenging the system. The post-war era shows the limit of economist demands. Social-democratic Sweden went as far as the Meidner plan, a vision to turn the means of production into workers’ control. The Meidner plan failed, and business began its counteroffensive. Workers were too invested in the system to significantly challenge this failure, and as of today, capital has slowly chipped away at many of the historical gains of Swedish social-democracy. As Lenin stated in Left-Wing Communism, revolutions can only triumph “when the “lower classes” do not want to live in the old way”.10 In this case, the “old way” was good enough, and workers did not fight to move from “social democracy” to “democratic socialism”.

In a country like the United States, revolutionaries must fundamentally look to challenge the political structure and form a broader vision of how the system should look. Sanders’ race-agnostic politics do nothing to address domestic white supremacy or the pillaging of the Global South. Sanders is right in that universalist policies such as a $15/hour minimum wage will primarily help people of color. But this does not do anything to change systemic discrimination. We have enough evidence to show that remedies in policing do not address the institutionalized white supremacy of law enforcement. Medicare for All might transform the way white supremacy is enforced in the healthcare system, but it is naive to think that it will eliminate it.

Centering race-blind social-democratic projects as a model is not enough. The Swedish social-democratic project was based around a relatively homogeneous “community of the free”. Today it shows deep cracks due to its inability to deal with the cultural and racial diversity immigration has brought in. Universal politics assume that all subjects conform to the same standards, and believe in the same project. With the racial diversity of the US, any universalist race-blind project is doomed if it does not explicitly address the faultlines of the working class. The most marginalized sections will simply not trust economist projects to include them. There is over a century of failures to attest to this, from the failure of Eugene Debs’ Socialist Party to significantly attract black members to Sanders’ inability in 2016 to compete in the Southern states. And even if we do win universalist demands, the cracks will show up later and will be used to reverse any gains. We just have to remember how Reagan leveraged the “welfare queen” that had an explicitly racist subtext.

V

Instead of a form of subjugation that can be remedied by economic means alone, we have to recognize the political character of white supremacy. The issue of slavery is at the forefront of this election cycle. A Trump presidency is the elephant in the room: the Obama presidency did not mean that we are post-racial. The 1619 project is actively shaping how people think of the United States, tying the foundation of this country to the first shipment of slaves. Led by the New York Times, it is receiving attention from the highest spheres. Some type of cosmetic reparations will feature in a 2020 Democratic platform as an attempt to attract back the black voters the Democrats desperately need. Several candidates, the most notable of which was Marianne Williamson, have proposed comprehensive platforms on the debate floor.

An electoral platform centered around destroying whiteness through indigenous justice and reparations is of paramount importance for socialists today. Some plans are simply not worthy of the name of reparations. Black self-determination plays a key role in this platform to both decide what reparations actually mean, and what to do with the money. Tax credits do nothing to address collective injustice, while the US government coming in to repair infrastructure in majority-Black neighborhoods does not address Black self-determination.

As socialists, we should never oppose reparations, as that would mean isolating us from the Black masses. We have to remember how the Bolshevik’s refusal to address the Bundist concerns led them to the hands of the Mensheviks. A debt of forty acres and a mule is owed, and this is the whole material heart of the Black national question. We should center that it is essential for Black people to decide on what reparations mean. We should not be afraid of not having a seat at that table, because that either means that we do not have enough Black members in our parties, or that our members are not fighting for proletarian hegemony within the Black movement. A council for deciding how and where to apply reparations can be a seed to building alternative power if wielded correctly.

Reparations are not an end-goal but we can use them today to ground the fight for black self-determination and to struggle against whiteness. Ultimately, any non-reformist reform cannot remedy the US’s flaws of racism. This assumes that atonement can be reached within the confines of the current nation-state. The United States’ sins are not a choice it can reverse, they are deeply embedded in the DNA of this country. The platform to cure the character mistakes of the United States can only be fulfilled by the dismantling of the settler-colonial white supremacist structure. Even a comprehensive platform for reparations in its present state is not viable in the current political climate. The same way that “Black Lives Matter” caused a proto-fascist antithesis in the shape of “Blue Lives Matter”, a reparations movement should expect to be attacked both rhetorically and physically.

Even the most flawed reparations platform recognizes the issues of white supremacy as central to the United States and transcends economism in a way Sanders is not able to. While Sanders just wants to make an American Sweden, our movement must go much further. We need a vision for a better world, beyond wonkiness and towards a greater inspiration if we are ever to escape the confines of capitalism. Even if the first and second Reconstructions were unfinished revolutions, they changed society much more profoundly than the New Deal ever did by destroying slavery and Jim Crow.

At the same time, these anti-racist revolutions unleashed collectivized hatred in intense ways that contributed to their later failures. Fascism is capitalism in decay, and reactionary elements are inevitable in any pre-revolutionary situation. Socialists need a comprehensive economic program to pacify white reaction by offering to pay better than the wages of whiteness. Revolutions based on rural or marginalized people can succeed, like Cuba, fall short like Nepal, or fail completely like Peru, depending on their ability to attract the urban wavering classes. Ultimately, any successful socialist program in the United States must incorporate both racial and economic justice. In the first case, to center it politically, in a Leninist manner. In the second, to provide an incentive for the wavering classes to follow.

- J. V. Stalin, Marxism and the National Question (https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1913/03a.htm)

- H. Haywood, For a Revolutionary Position on the Negro Question (https://www.marxists.org/history/erol/1956-1960/haywood02.htm)

- H. Haywood, “Black Bolshevik”

- A longer history of the Bund can be found in “The Oath: The Story of the Jewish Bund” by Doug Enaa Green.

- “Fatherland or Mother Earth? Nationalism and internationalism from a socialist perspective” by Michael Löwy

- C. Carson, “The autobiography of Martin Luther King”

- In a historical irony, Lenin used the example of segregated schools in the US South to oppose the Bund’s ideas.

- See for example, “The Case Against Reparations”, Adolph Reed Jr., https://nonsite.org/editorial/the-case-against-reparations

- Geoff Mann, “In the Long Run We Are All Dead”, Verso, 2017.

- V. I. Lenin, “Left-wing communism, an infantile disorder” (https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1920/lwc/)