Amelia Davenport provides a brief overview of left-wing approaches to scientific management and argues that this field of inquiry should be embraced by socialist labor militants today.

Introduction

The global workers’ movement is in a period of defeat. Over the last half-century, union membership has declined precipitously in the United States and abroad. Whether out-voted in decertification campaigns or state repression using tactics like death squads in the global periphery, unionists collectively have been back on their heels. Of the experiments of working-class rule, only a handful remain—warped and deformed by constant siege. Meanwhile, the power of employers seems stronger than ever. But all is not lost. There are workers and other opponents of this process fighting back as we speak. But how will the working class triumph?

The study of the labor process has largely been left to those employed by capitalist firms. These firms prioritize their own profitability over other considerations, and so their analysis of work is directed toward figuring out how to achieve greater profit. As Marx wrote in Capital of the bourgeoisie, “The restless never-ending process of profit-making alone is what he aims at. This boundless greed after riches, this passionate chase after exchange-value, is common to the capitalist and the miser; but while the miser is merely a capitalist gone mad, the capitalist is a rational miser. The never-ending augmentation of exchange-value, which the miser strives after, by seeking to save his money from circulation, is attained by the more acute capitalist, by constantly throwing it afresh into circulation.”1 Other considerations, imposed by state regulations, worker resistance, and general cultural sentiment/norms also factor into the study and practice of labor organization, but they act more as constraints from the perspective of business than goals in themselves. For instance, concerns around safety, pollution, or workplace satisfaction act as objects of study insofar as they’re essential to achieve greater profitability. Marx famously cites capitalists sponsoring labor reform legislation that reduced the working day so that they would no longer be compelled to degrade their own workers by competition. Of the Factory Acts he writes, “these acts curb the passion of capital for a limitless draining of labour-power, by forcibly limiting the working-day by state regulations, made by a state that is ruled by capitalist-and landlord.”2 But the values of capitalist firms are not the only values that can guide the study of work. Values like greater worker fulfillment, more rational organization for social needs, ecological concerns, or consumer interests all have claims on the production process beyond the maximum return on invested capital.

Management theorist Peter F. Drucker once said “the best way to predict the future is to create it.”3 The role of a labor organizer then is to do the same. But how can we “create the future?” Understanding the dynamics of work is vital for any program of action that seeks to improve the conditions in which workers conduct it. Both in a positive sense of creating a vision for how work can be made better, and as a strategic tool for halting productive flows. In this article, I will sketch the hidden history of the scientific study of labor beginning with the scientific management movement through a few key members of the the Taylor Society, the ways in which organized workers responded to the consequences of their reforms, and the use of the products of the application of science to the labor process for informing labor militants today.

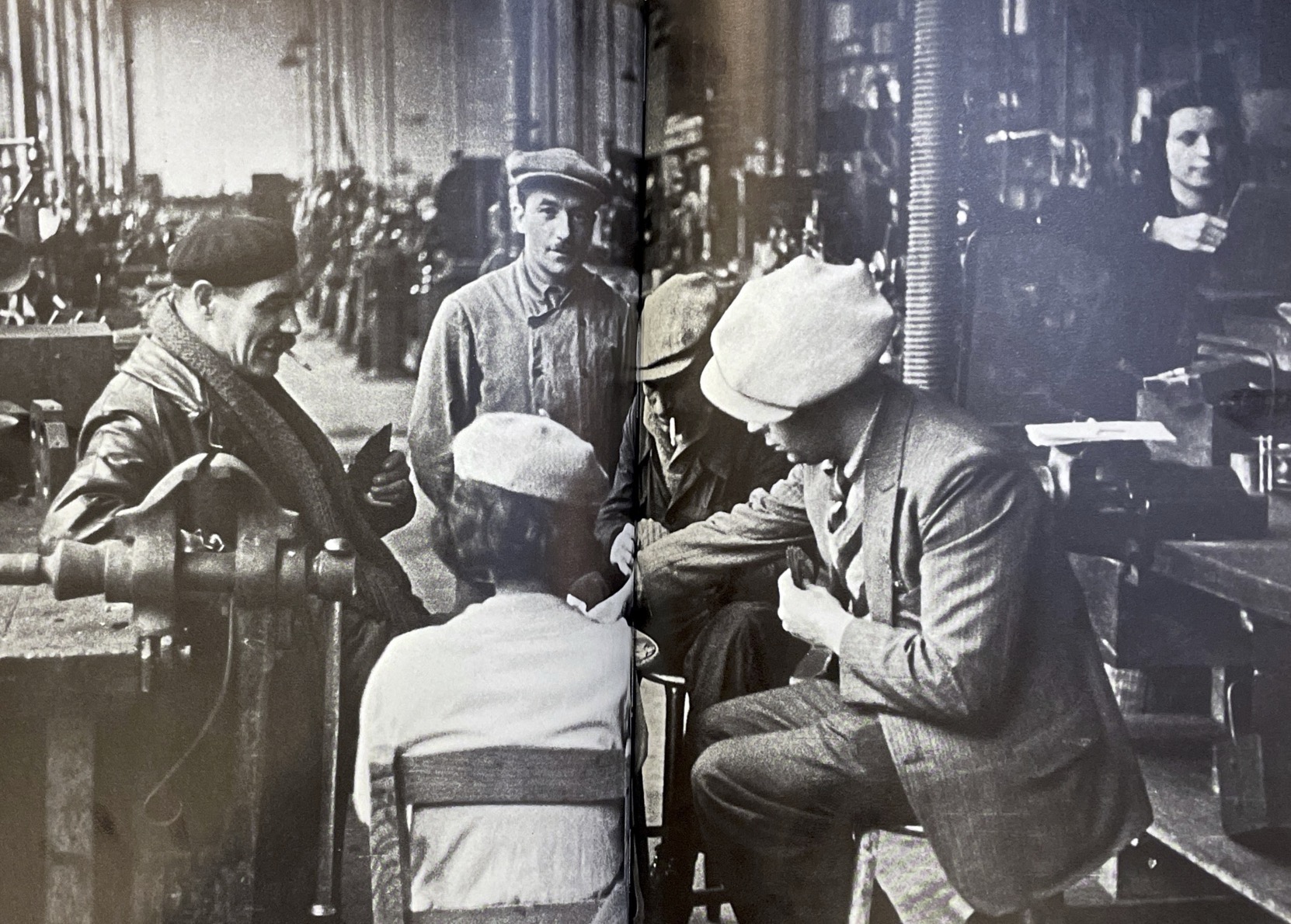

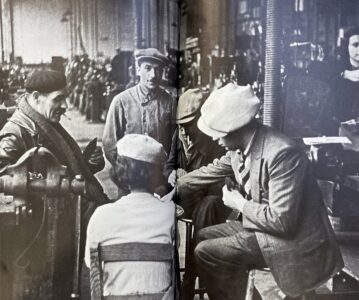

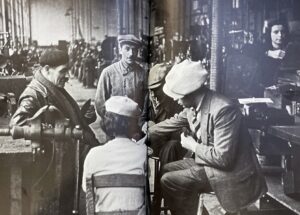

The Stopwatch, the Camera, and the Slide Rule

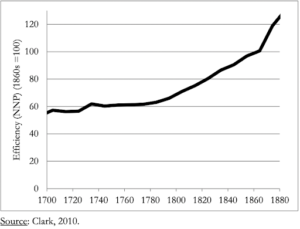

With the steam engines perfected by Thomas Newcomen and James Watt, followed by inventions like Edmund Cartwright’s power loom and Joseph Jacquard’s programmable loom, the Industrial Revolution radically altered how work was conducted. These innovations were adopted in a widespread manner, as argued by Andraes Malm and others, in large part as a response to rising class struggle.4 This was especially as Marx noted because of the creation of a large surplus population to utilize them due to the enclosure of the commons. The essential ingredients for the revolution being private manufacturers contending with petty bourgeois craftsmen, a large mass of available cheap labor, available cheap raw materials from the colonies, and sufficient social surplus to sustain a growing number of intellectuals. Productivity skyrocketed, more than doubling in England from 1700 to 1880.5

Beyond the quantitative expansion of production and further immiseration of the colonies, this process gave rise to a new group of workers: those who designed the machines used in the factories. They were the first professional engineers. Not independent craftsmen, nor unskilled proletarians, nor pure intellectuals, they more closely resembled specialist layers seen in classical tributary societies like the Inca, Achaemenid, and Mauryan empires. The key difference being the members of this new layer sold themselves as mercenaries to rival capitalists, rather than serving as retainers to the sovereign authority. Gradually this layer of workers began to cohere. In 1880, a group in the United States formed an association called The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME). It was in 1905 that their organization solidified into a purpose beyond collegiate discussion. The Grover Shoe Factory Disaster in Brockton, Massachusetts, caused by a boiler explosion, provoked the ASME to issue industrial standards, and standardized safety procedures, which were codified into law in both the United States and Canada.6 The notion that there was “one best way” to test the safety of boilers had enormous ramifications.

In 1911, the former president of the ASME, Frederick Taylor published a pamphlet called Principles of Scientific Management, which was secretly co-authored by Morris Cooke.7 Taylor and Cooke proposed extending the principles of mechanical engineering from the machines themselves to those operating the machines. Taylor decried the way in which labor processes operated according to “rule of thumb” logic, rather than rational or empirical insights.8 No longer was the bottleneck in production the rate at which machines operated, but rather how well workers could use them. In response, Taylor broke down labor activities into their constituent parts, introduced studies of the motions of workers, and assembled teams of engineers to determine the optimal methods of conducting tasks. This meant the safest, least wasteful, and most productive method: the so-called “one best way.” For instance, Taylor and his assistants developed a “science of shoveling” and demonstrated scientifically the need for periodic breaks when carrying heavy objects.9 These methods were then generalized to the entire factory and implemented by a new system of “functional foremen” which broke up the different aspects of management among specialists. Taylor’s rationalization of labor reduced the skill needed for a worker to do many jobs, which made labor more expendable and extended employment opportunities to many more workers. Taylor also introduced the idea of a “planning department” in the factory for the rationalization of materials and the direction of workflows.

Taylor’s reforms were not without difficulties. Many rank and file workers resented having their activities so tightly controlled, and craft unions saw the “de-skilling” of their labor as an existential threat.10 Taylor was called before the US House of Representatives in 1912 due to serious public concerns about the dehumanization which critics alleged the Taylor system imposed.11 In his testimony, Taylor claimed that scientific management was not a particular set of techniques, piece rate system, or way to organize a shop that can be directly implemented. Instead, it consisted of a “mental revolution.” Taylor said that the essence of scientific management was shifting the perspective of labor and capital both from the division of existing surplus to the increase of absolute surplus and therefore greater living standards for both sides. And this shift in perspective required a commitment from all parties to following the ‘best’ production techniques. Taylor further pointed out that workers in shops under scientific management methods earned between sixty to one hundred percent higher wages than before.12

But objections remained that workers were disempowered and reduced to mere beasts with all thinking handed to experts. This was best articulated by Harry Braverman in Labor and Monopoly Capital, “the more science is incorporated into the labor process, the less the worker understands of the process; the more sophisticated an intellectual product the machine becomes, the less control and comprehension of the machine the worker has.”13 What Braverman misses, however, is that while control and application of knowledge of the labor process had become concentrated on the side of management, that knowledge had also taken on the character of social knowledge rather than individual skill. The primitive accumulation of craft skill by capital creates the conditions for the socialization of knowledge. Marx discusses this process in the Grundrisse:

Nature builds no machines, no locomotives, railways, electric telegraphs, self-acting mules etc. These are products of human industry; natural material transformed into organs of the human will over nature, or of human participation in nature. They are organs of the human brain, created by the human hand; the power of knowledge, objectified. The development of fixed capital indicates to what degree general social knowledge has become a direct force of production, and to what degree, hence, the conditions of the process of social life itself have come under the control of the general intellect and been transformed in accordance with it; to what degree the powers of social production have been produced, not only in the form of knowledge, but also as immediate organs of social practice, of the real life process.

…

The saving of labour time [is] equal to an increase of free time, i.e. time for the full development of the individual, which in turn reacts back upon the productive power of labour as itself the greatest productive power. From the standpoint of the direct production process it can be regarded as the production of fixed capital, this fixed capital being man himself. It goes without saying, by the way, that direct labour time itself cannot remain in the abstract antithesis to free time in which it appears from the perspective of bourgeois economy. Labour cannot become play, as Fourier would like, although it remains his great contribution to have expressed the suspension not of distribution, but of the mode of production itself, in a higher form, as the ultimate object. Free time – which is both idle time and time for higher activity – has naturally transformed its possessor into a different subject, and he then enters into the direct production process as this different subject. This process is then both discipline, as regards the human being in the process of becoming; and, at the same time, practice [Ausübung], experimental science, materially creative and objectifying science, as regards the human being who has become, in whose head exists the accumulated knowledge of society. For both, in so far as labour requires practical use of the hands and free bodily movement, as in agriculture, at the same time exercise.14

The organization of understanding across individuals, the ‘social brain’ and ‘general intellect’, which Marx claims are made concrete under capitalism in the form of fixed capital goods, represent the progressive growth of the potential for human freedom. For Marx, and his collaborator Engels, freedom is often conceived from two directions, both expanded through the development of the social brain: 1) freedom measured as ‘free time’ in which individuals are free to either pursue idle leisure or develop themselves in higher pursuits, and 2) freedom as measured as the ‘recognition of necessity,’ and greater scientific understanding of nature through labor which allows humans to accomplish social ends.15 However, under Capitalism, the social brain is absorbed into Capital and estranged from workers. The products of collective social knowledge become privately owned machines that demand the worker conform to specific actions without requiring their comprehension. Braverman is right to not only oppose this social enclosure of science in the form of fixed capital but also right in opposing the extension of enclosure over the knowledge produced about the physical and motor actions of workers in the labor process. But he is wrong to oppose the creation of this knowledge, even under capitalism.

The Utopian Socialist Robert Owen, as I have argued previously,16 was properly speaking the first scientific management theorist. His experiments in labor organization, including a form of public work-status indication, prefigured efforts by the Taylor Society by over half a century. In the passage from the Grundrisse cited above, Marx quotes Robert Owen thus: “Since the general introduction of soulless mechanism in British manufactures, people have with rare exceptions been treated as a secondary and subordinate machine, and far more attention has been given to the perfection of the raw materials of wood and metals than to those of body and spirit.”17 Marx, perhaps naively, follows Owen in seeing the deformation of labor by capitalism principally in the blind domination of workers by the physical instruments of labor, not in the privatization of the means of ‘perfecting the body and spirit’ in the labor process. But even as the demonic furnaces of capitalist machines, when liberated from their status as fixed capital, and re-absorbed by the collective worker as its inorganic limbs, can become instruments of freedom in communism, so too can the sciences of the organization of human labor.

Returning to Taylor, his views shifted over his life in response to developments like the insights of Henry Gantt discussed below. In part because employers were increasingly unreceptive to losing managerial prerogative to the engineers, Taylor ultimately came to endorse worker participation in management, which led to the Taylor Society’s embrace and promotion of co-determination between unions and management in the creation of labor policy.18 This neatly encapsulates a contradiction within capital itself: capital as property engaged in the concrete production of use values versus capital as abstract property free from any particular use value signifying real social power to direct productive development. Taylor attempted to join with unionists as bourgeois subjects (collective property owners of labor power) to fight for more rational production for social need against the self-expansion of capital. In this he was doomed to join all other efforts at abolishing capitalism without abolishing capitalism.

Responding to the concern of worker disempowerment, Taylor’s protege Henry Gantt developed an alternative model of scientific management detailed in Work, Wages, and Profits. Gantt’s improved model centered education for workers on the scientific principles that govern their work and formal feedback channels through which workers could suggest improvements to labor methods and machines. Gantt proposed a break from traditional managerial practices of disciplinary control and threats in favor of joint scientific cooperation: “Whatever we do must be in accord with human nature. We cannot drive people; we must direct their development… The general policy of the past has been to drive, but the era of force must give way to that of knowledge, and the policy of the future will be to teach and to lead, to the advantage of all concerned.”19 While planning and design of work was still largely directed by the engineers, workers not only gained the ability to exercise their intellectual faculties but there was now a path for them to become engineers themselves. Gantt found that not only were workers less alienated, but worker participation improved efficiency more than Taylor’s technocratic approach.

Gantt was disgusted by the way in which capitalists placed profits over the community good. He would go on to become a moderate socialist of sorts under the influence of left-wing economist Thorstein Veblen. He also took some inspiration for the Soviet Union’s attempt to organize an economy in the interests of the people rather than profit. In Organizing for Work, Gantt proposed socializing and democratizing corporations, broadly increasing worker control of production, to ensure they serve the interests of the public. He also wanted to transfer day to day managerial control from the capitalists to the engineers.However, Gantt stopped short of arguing for full public ownership, as he claimed that, were firms under democratic social control, the form of ownership is irrelevant.

In the text, Gantt moves from Taylor’s conservative liberalism and prefigures the arguments of leaders in the Communist Party of China and post WWI Social Democrats that private shareholding is compatible with social control over production insofar as investments are directed toward the public interest, perhaps unwittingly echoing Marx’s naive hopes about the development of joint-stock companies representing a step toward the socialization of production. But the notion that engineers ought to be placed in charge of executing the democratic vision, rather than civil servants, was a uniquely Veblenite theory. In Gantt’s view, “engineers were the only members of the community who understood the needs of the nation, desires of the workmen, and the power of the productive forces.”20 Gantt wanted to turn scientific management into an instrument for democratic institutions to direct the fulfillment of social needs through the cooperation of workers and engineers. Such views, like Taylor’s, misunderstand the nature of private property, the causal power of the circuit of capital, and the historic mission of the working class (as opposed to relatively powerful intermediate layers like engineers). It is important to understand Gantt’s work dialectically. As a body of ideological theories, it represents a failed attempt by an intermediate class in the productive process to resolve the class struggle. But in his scientific study of labor, Gantt’s work represents a major contribution to the effective production for need and reduction of waste through the inclusion of workers in the mastery of their own production.

A close friend and ally of Gantt’s, Walter Polakov is a forgotten but crucial figure in both American and Russian management history. Polakov was a Russian immigrant and dedicated Marxist. There was no real contradiction between these two aspects of his life. In debates within the Taylor Society, Polakov frequently quoted Marx, Rosa Luxemburg, and Karl Kautsky.21 And he used his engineering and scientific management training to support workers in class struggles. In management, Polakov pioneered the scientific organization of power plants and industrial diagnostics. But he also levied sharp critiques against Frederick Taylor’s system. In To Make Work Fascinating, Polakov draws on physiological studies which demonstrate that sustained repetitive work causes nervous damage to workers with many deleterious consequences ranging from mental health to physical damage. In a direct response to a comparison Frederick Taylor once made between unskilled workers and “trained gorillas,” Polakov opens the text, “Confusion of classes of life has resulted in the building up of industry around the mistaken idea that the workman is an animal and his work a commodity.”22 Polakov sought to reaffirm the essentially human character of work and the role of the worker as a creative, rather than simply mechanical, agent. He further lays out the faults scientific management as a movement, led by Gantt and Polakov’s other colleagues like Morris Cooke, had discovered with Taylor’s system:

The early attempts to make workers personally more efficient are generally connected with the Taylor system of management. The characteristic features of this system are (a) specialized division of fiction, and (b) detailed time studies of operation. A score of years of trial of this system has clearly demonstrated its inherent, organic short-comings in many industrial establishments. (A) Functional foremanship, with brain work divorced from manual work has made the performance of work still more automatic and irresponsible. Creative, intelligent work has also been removed from the shops themselves and concentrated in a planning department or general office, which lacks direct personal touch with workers. (b) Time studies and instruction cards, by standardizing workers’ manipulations, have caused the operations to become still more monotonous, repetitive, without variations and devoid of stimulating self-expression.

Time studies, motion studies and other means of studying the work are in themselves commendable as steps toward substitution of “guess” and “opinions” by measured facts. Unfortunately, however, all these means lead to standardization and mechanization of manipulations. Once man is lowered to the level of an automaton, the creative element is driven out of his work and subsequent difficulties are impending. Again, while the studies are being made, a healthy, stimulating interest in the work is arounds, especially if workers’ cooperation is invited; but once completed, tabulated, registered and prescribed, they become a monotonous routing. Vigorous protests and even some legislation against this dehumanizing application of scientific methods in an unscientific manner have been the inevitable results. Recognition of these fatal mistakes has prompted industrial engineers to concentrate on the shortcomings of management itself. These efforts have (1) decentralized the detached intelligence of the planning department by establishing manufacturing offices in the shops, (2) reunited the instructing and inspecting functions of foremanships, (3) substituted for time-study clerks the direct interchange of workers’ skill and intelligence, (4) stimulated interest in the work by training and providing instruments for intelligence control of processes, (5) liberated the suppressed creative instincts of workers by providing them with means of observing their own progress, and finally, (6) devised a charting method permitting the accurate measurement of managerial efficiency separately from the efficiency of workers.

Polakov envisioned the scientific management of work as a participatory and democratic practice. Where the manager had transitioned from an arbitrary tyrant into an objective technician under Taylor and Gantt, she became a leader and colleague in Polakov’s vision:

It is now generally recognized in industry that idle equipment is harmful; the greatest source of waste is to be found in the idleness of our available knowledge and creative capacities of men, which are not liberated and applied productively under the mechanistic, formal organization. The greatness of a new industrial leader will lie in his ability to liberate the creative forces within men, as against relegating them to the level of animals carrying burden and doing machine-like work. In the author’s experience. In promising and increasing industrial efficiency, he has found that the most fundamental, most successful and most enduring way to do it is in the elevation of man to his true dignity as an intelligent, creative agent. We arrange his work so that it requires the exercise of his mental and spiritual faculties and capacities. We make his job interesting, sometime exciting, often fascinating. This way we liberate his creative capacity, give him a measure of satisfaction in what he is doing and only then are we able to reduce that waste which constitutes our sad national characteristic. To be specific, the monotonous physical labor of a fireman is regularly transfigured by special training into a fascinating game based on the exact sciences of physics and chemistry, requiring an exercise of mental capacities. Watching and interpreting a simple array of instruments provides men with interest, which is augmented as they intelligently control a process and watch the results attained.

Charting the progress made in elimination of waste of material provides further source of satisfaction in observing one’s own improvement in the mastery of processes through the acquisition of knowledge and skill. These charts are plated on the basis of what is possible of accomplishment with a proper exercise of intelligence, knowledge, and skill, and the short bars indicate the falling short of possibility. Sometimes it is found that a playful spirit of friendly competition or just pride in self-improvement and accomplishment prompts men to draw similar records on the fronts of their boilers or elsewhere in the room. When men find themselves thinking about their job it loses its monotony. Moreover, the amount of physical labor is reduced in some inverse proportion to the intelligence applied.23

Polakov went on to work in the Soviet Union during the first 5-Year Plan and introduced pro-worker reforms as well as the use of the Gantt chart. He returned to the U.S. and worked in the New Deal administration before working for John L. Lewis in the United Mine Workers. Polakov used his knowledge to help the miners successfully win improved safety regulations.24 Sadly, Polakov died penniless after many years of harassment by the FBI, social ostracism due to his immigrant status, and his political beliefs in the U.S.’ increasingly anti-communist climate.

Like Walter Polakov, Mary Van Kleeck was a Taylor Society member and revolutionary Marxist. Van Kleeck is an incredible figure; she began her career as a member of the Russell Sage Foundation, where she served as director of the Department of Industrial Studies, studying the conditions of female textile workers.25 She was a part of a unique generation of lesbian radical social workers like Jane Addams and Mary Parker Follet. Van Kleeck saw in scientific management a way to combat the arbitrary patriarchal abuse of employers and improve the conditions of women as well as reform the whole of society for the better. Scientific management opened the door for “novel work” for women in industries that had previously been the exclusive domain of men. Van Kleeck saw in Taylorism a path to create a genuinely scientific approach to solving industrial problems, provided that in its embrace of ‘human factors’ it maintained its commitment to science rather than embracing ‘humanistic’ sophistry in the form of the human relations movement. Van Kleeck wanted scientific management to embrace the principles of social work and vice versa. Scientific managers could use the social scientific investigative methods of social work to analyze the context of production while social workers could leverage Taylorism’s insights to propose effective reforms to the conditions of labor. She saw in Taylorism’s scientific approach a similar “constructive imagination” for solving social ills as existed in social work:

Those answers did not relate merely to what is called the human element in the industry, conceived as a separate problem in a different compartment of the manager’s desk. My interest in the contribution of scientific management . . . was not solely in its emphasis upon personnel relations, but in the technical organization of industry as it affects wage-earners. The constructive imagination which can spend seventeen years studying the art of cutting metals is the imagination that can make industry and all its results in human lives harmonize with our ideals for the community. That kind of constructive imagination, though it may deal with one technical problem, will not fail to envisage the whole significance of industrial management. Nor will it be content merely to increase profits. The philosophy and the procedure that it represents will ultimately build a shop whose influence in the community will be social in the best sense because the shop and all its human relations are built on sound principles.

Therefore, my interest in the Taylor Society is not directed toward challenging the technical engineer to give attention to problems of human relations. I am not worried about that, because if he is a good engineer he cannot fail to contribute to human relations. I am concerned rather with the other end of the story. I am eager to have those people who see the present disastrous results of industrial organization in the community realize how the art of management in the shop can fundamentally change those social conditions in the community.26

Van Kleeck followed a similar trajectory to Gantt. She claimed that the profit system and private ownership in the hands of production “tied scientific management to a hitching post” and that “to untie scientific management so that it could assume its rightful social role” there must be “public trusteeship over corporate use of national resources.”27 She would, however, move in a much more radical direction than Gantt. Where Gantt saw the Soviet Union as engaged in an admirable task of transforming production for social use instead of profit but ultimately an undesirable model to emulate, Van Kleeck fully endorsed the Soviet model of economics. Van Kleeck was awed by the relatively egalitarian social relations between men and women she found on her visit to Russia. She was doubly impressed by the way in which resources were coordinated to maximally benefit their society rather than private interests, especially in the elimination of unemployment.28 Van Kleeck observed of the Soviet system, “the procedure of planning is developing on fundamentally sound lines in that it is being decentralized in such a way as to ensure the participation of those who are closest to the actual work in a given unit of industry.”29 Whatever we may think of the Soviet Union now, there were thousands of people working and applying their creative efforts to get food on the table and provide a robust standard of living in a nation that went from a country of illiterate peasants to an industrial superpower in a generation. Van Kleeck witnessed the genius and creativity these dedicated communists committed to the cause, even given the hardships of their country’s position in the world. Van Kleeck’s vision of planning, stemming from these experiences, was far more participatory than the labor organization of American firms.

Van Kleeck was not just an admirer of scientific labor organization, however. She was actively involved in the creation and dissemination of labor statistics as a part of both reform and scientific labor efforts. She, and her girlfriend Mary Fleddérus, worked with Marxist economist Otto Neurath on employing his pictorial statistical methodology “Isotype” in the United States to make knowledge increasingly accessible to the public. She further joined the American Labor Party to promote the interests of the union movement, even running on its ticket in New York, organized social worker strikes, and was integral to the social worker “rank and file” unionization movement of the Depression and New Deal era.30

Polakov and Van Kleeck each took from the framework of scientific management a different critique of capitalist production. Where Polakov critiqued the misapplication of scientific methods within the labor process, Van Kleeck decried the lack of scientific coordination above the firm level. What both shared was a commitment to a vision of Industrial Democracy in which the tools of science served the people rather than acting as instruments for enriching a small oligarchy of capitalists. But while Polakov’s humanistic rebuke of the monotony of work gets close to overcoming Taylorism’s failure to reach its stated goal of providing meaningful prosperity to all, it is not fatal. Taylorists, including those Marxists who care chiefly for the quantitative expansion of production, could conceivably argue that so long as Van Kleeck’s vision of social planning, as in the Soviet Union, is introduced, the trade-off of degraded working conditions is worth the freedoms and wealth gained outside of work. But within management science itself, a successful critique of Taylorism on its own stated terms shows us a path toward a truly rational economy.

An Ongoing Process of Improvement

The scientific basis for overcoming Taylorism had its germ in an institution called Bell Labs. A research institute created by the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, Bell Labs was responsible for facilitating the development of revolutionary technologies like the transistor (that makes modern computing possible), the laser, the Unix operating system (the precursor to both Linux and MacOS), and solar cells.31 The institution was home to luminaries like Claude Shannon, the father of Information Theory, Max Mathews, the creator of the first electronic music creation software, and William Shockley, who led the team that developed the transistor. It was here that a physicist turned engineer named Walter A. Shewhart would uncover the principles behind what we now call statistical control theory.

Coming from AT&T’s manufacturing division, Western Electric, Shewhart took work he developed while assigned to improve audio signal quality in telephone lines and realized the same underlying statistical dynamics were occurring in manufacturing.32 He developed a prototype of what would become a ‘process control chart’ and laid out the core principles of quality control: 1) reduce variation in the product 2) prevent defects before they happen rather than adjusting to them. Shewhart had discovered not only that unintended variations introduced at each step of the manufacturing process created enormous waste but that it was possible to distinguish between human-caused (and therefore controllable) and randomly caused variations or defects.33 Shewhart’s control charts were deployed to identify where machines, bad practices, or managerial failures were creating continuous waste.34 It was necessary to intervene in the process sequentially before defects emerged because simply responding to them only created more variation by shifting worker attention and amplified the problems even more. Rather than merely inspecting for defects after they happened, it was now possible to continuously monitor production as a flow. This had the side effect of shifting responsibility for defects away from rank and file workers to the managers in charge of organizing the work processes. Previously at Western Electric and other firms, systemic faults in the production process were assumed to be the fault of the laborers on the shop floor. The mistakes of management were ‘externalized’ onto workers who were expected to simply make do through heroics to meet production targets or face disciplinary action.

Shewhart also initiated the most important scientific intervention into production of the 20th century. He created a simple formal method for improving any productive process. Later formalized as the “PDCA” loop, which stands for Plan, Do, Check, Act, is a scientific framework for continuous process improvement.35

In the Planning phase, you formalize your goals and lay out the methods you intend to use to reach them. In the Do phase, you carry out the ideas of the Planning Phase. In the Check phase, measurements are gathered of the results and they are compared against the projected figures of the Planning phase (this is called a ‘gap analysis’). This allows you to pinpoint where improvements are needed. In the Act phase, a root cause analysis is undertaken to identify the true source of defects or problems and make adjustments to prevent the problems from continuing to manifest. The result should be some kind of new process, set of priorities, standards etc. This cycle is repeated continuously, with the methods and practices of improvement themselves becoming refined over time.

The importance of the Shewhart cycle is not just that it has objectively improved the process of production everywhere it has been deployed, from AT&T’s telecom infrastructure to Japanese manufacturers like Toyota and Hitachi,36 but that it represents a generic scientific method anyone can in principle participate in. Where Frederick Taylor’s technocratic vision of production centralized process improvement into the hands of expert-engineers, the PDCA loop requires the active participation of the workers immediately engaged in the work.

The worker participation intrinsic to the successful use of the PDCA loop would be later formalized and popularized by Shewhart’s protege W. Edwards Deming at Bell Labs as “quality circles” within the “Total Quality Management” movement.37 These initiatives have mostly died out and been superseded by ‘Kaizen’ circles imported from Toyota since the 1990s. The premise was that it’s those who are closest to a task that are the most informed about it. Members utilized the PDCA cycle on a continuous basis. This is the exact opposite of Taylor’s theory that only trained engineers were capable of understanding how to solve the problems of work. Quality circles took two forms, organic initiatives created by workers to solve problems they faced as well as initiatives sponsored by senior corporate leadership with active rank-and-file participation. In both cases a circle tended to be between three and twelve participants, at least one of whom was a responsible manager that would present their findings to senior leadership.38 Quality circles met once a week, generally received training and advice from technical specialists in areas like statistics, problem identification, root cause analysis, and visualization. Time spent in quality circle meetings was also paid on the clock which gave a reprieve from normal work. Members were free to choose any topic related to production that interested them outside of areas reserved for union bargaining like pay.

Two major issues with the quality circle movement existed: 1) circles initiated by senior leadership were significantly more likely to have their proposals implemented.39 While not negating the rank and file participation, this belies the idea that quality circles really were completely egalitarian because worker-initiated circles received less attention and support. In practical terms that meant continuing to use more wasteful or otherwise problematic practices. It makes sense that in a corporate hierarchy the leadership would be more invested in things they sponsored, but this points to structural problems beyond the scope quality circles could address. 2) Once enthusiasm waned and participation began to decline, a quality circle would become very ineffective at producing new improvements. This greatly hindered the sustainability of quality circles both as a process improvement tool and as a means to institutionalize worker participation in the development of production.40 A more superficial problem, though one far more fatal to quality circles as a historical movement, is the tendency of capitalist management towards fads and adopting innovations in name while not really committing to them. An endless number of C-Suite executives push a flavor of the week reform only to move onto the next one after wasting many hours in widespread training without ever changing the real operations of the firm. While quality circles did produce concrete improvements in their time, the structural incentives of capitalist firms meant that the underlying concepts would have to be reintroduced under new banners like Six Sigma and Kaizen every few decades.

W. Edwards Deming did more than just popularize Shewhart’s work, he expanded and advanced the burgeoning science of industrial quality control. His greatest contribution was in Japan where he served as an advisor during the post-WWII economic recovery efforts.41 Deming trained Japanese engineers and managers in statistical control theory and found a far more receptive audience than he’d found in the U.S. Many of the concepts Shewhart developed, like building control against defects in advance rather than correcting after, were already integral to Japanese methods. Toyota’s mechanical looms had error prevention built in, stopping to alert the user before creating a problem, due to their philosophy of ‘Jidoka’ pronounced the same as the Japanese word for ‘automation’ but modified to include the notion of human intelligence. But Deming provided a formal statistical and mathematical approach to these problems that greatly aided Japanese efforts in rebuilding their industrial system. Deming was an implacable enemy of the American industrial mode of mass production of shoddy goods and quantitative expansion for its own sake through marketing. Instead, he envisioned a reorientation of industry toward durable, reliable goods which served the needs of people.42 Deming’s industrial system would be able to rapidly adapt and meet needs quicker than our current mass-production oriented economy while greatly reducing resource use. He also opposed the use of performance evaluations tied to reward and punishment so prevalent in American industry. Deming believed that grades of any kind, including those in school, only exist to destroy people and elevate a self-reproducing minority which can then hoard resources and opportunities. Systemic failures in a job are the fault of supervisors for either inadequately training or more often mismanaging the worker. Moreover, in the vast majority of contemporary work processes, success or failure is collective and it makes no sense to judge an individual based on arbitrary metrics. In cases where the worker genuinely was inadequate for the role, being able to move them to a different role for which they could be properly trained and supported in without the fear of financial consequences is essential. However, the flip side of these views was that, contrary to American norms, Deming believed job mobility to be very destructive, as he thought reaching peak performance at a job required several years or more. However, what Deming proposes is a scientific management that strikes at the root of Taylor’s technocracy by centering rank and file workers while advancing Shewhart’s generic scientific process.

Two other key figures in the Quality movement worth further study are Kaoru Ishikawa and Joseph Juran. Each of them made enormous contributions to the scientific study of the labor process and created practical tools for analyzing problems so that we can solve them. Ishikawa in particular developed a cause-and-effect chart often called a ‘herringbone chart’ that allows a team to map out dependencies that produce effects like defects and thereby determine how to improve product quality.43 Juran for his part was integral to developing theories of change management and personally led the charge to break from outdated practices developed by the Taylorists for organizing work.44 Juran’s most lasting influence was in organizing trans-national training sessions between the United States and Japan that popularized and spread the methods and philosophical insights each had developed which supported the elevation of quality.

Standing on the shoulders of these and other giants is Eliyahu M. Goldratt, the theorist who finishes the job of overcoming Taylor’s system. Goldratt, like Shewhart and Deming, was originally a physicist by training. Most famous for a theoretical framework in manufacturing called the Theory of Constraints, Goldratt was something of a throwback to the natural philosophers of the early scientific revolution. Fundamental to his worldview, and in the tradition of Aristotle and Newton, was the conviction that there are no immutable contradictions in nature.45 He detailed his philosophy, illustrating through case studies drawn from his career as a consultant, in a socratic dialogue with his daughter titled The Choice. His work is fascinating, detailing an essentially dialectical approach to organizational change and a method of mapping causal relations that allows a team to create targeted interventions to change dynamics in a desired direction where they are most effective.

Goldratt pioneered an entire genre of books, the ‘business novel’ in which practical skills and theories for leading organizations are imparted through a parable. The most exemplary texts in this style is The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement and its less read sequel It’s Not Luck. The Goal details the life of Alex Rogo, the manager of a soon-to-be-closed manufacturing plant in a failing company and husband in a failing marriage. Through the yoda-like mentorship of a professor named Jonah (an obvious Mary Sue for Goldratt himself), Alex successfully improves the bottom line of his factory well enough that not only is the plant saved (and his marriage) but he and some of his subordinates are promoted. Such a saccharine sweet story hardly seems of interest to communists, but it is the methodology and principles laid out in the text that are important.

In The Goal, Goldratt lays out a series of key notions that are vital to understanding both manufacturing and organizations in general:

- All activities which do not support the goal of the organization are waste from the perspective of reaching it. This should be self evident but it’s getting clarity on what exactly the goal is that matters here. You cannot define waste without defining the goal.

- In every goal oriented system, there are a number of steps necessary to reach the goal, and the slowest step is the system’s constraint. This is true whether you’re producing widgets, software, or canvassing for a political candidate.

- There are always dependencies between steps and they transmit the effect of statistical fluctuations. To put it more simply, to achieve a goal, some steps can only happen after other steps have (for example, you can only butter toast for your breakfast after the bread has been heated). There is a chance that each step could finish slower or faster than average. However, once you reach a bottleneck, only delays are accumulated because finishing early only allows work-in-process to pile up. Any time lost at a bottleneck is lost forever, you can’t get it back somewhere else in the system. Moreover, the constraint of the system must be ‘elevated’ and set the pace for the entire system.

- Metrics must measure progress to the goal; otherwise they are a meaningless distraction. Goldratt argues that the purpose of metrics in production is to produce specific behavior rather than collect data in the abstract. Existing metrics that considered product inventory, machines, and work-in-process as positive on the balance sheet created perverse incentives to tie up more resources rather than actually deliver goods to end users.

- Batch sizes should be reduced as small as possible: ideally to a single-piece flow. This allows for both a faster flow and a reduction of tied up resources as work-in-process. Think about a restaurant. If you can assemble each meal to order and only use exactly the resources as they’re needed at each step you can deliver a higher quality product and reduce the potential for delays. For instance, if you have to wait on a large batch of handmade pasta to finish before several steps for a large number of orders, which themselves have large batches, you will set yourself up for delays.

- Local optimization is destructive if not subordinated to global optimization. In other words, not only should the overall system be prioritized, but it’s actually counterproductive to increase efficiency in many cases. Anywhere you increase efficiency other than at a bottleneck process, at best you’ve wasted effort, potentially overloading the system with excess work, or worse you reduced the ‘slack’ in the system which makes it more brittle. Goldratt distinguishes between resource utilization and exploitation. When a resource is utilized, it isn’t necessarily actively in use but is ready and available if needed. If a resource is exploited, it is actively employed. Contemporary capitalist managers often attempt to maximally exploit the resources under their control, including workers, which on paper appears to increase efficiencies, but in practice it leads to systemic stress and disruption. Goldratt instead advises ensuring there is adequate redundancy and not requiring workers to be ‘busy’ at all times if their role isn’t a bottleneck process.

- Coming from point 6, systems need proper buffer management. With buffers set up at different levels of organizational scale, availability issues for goods can be smoothed out. It’s much easier to plan how many trains or cars, and what types, are needed for a continent than it is for a particular town. However, you can project what is most likely, and what will be consumed fastest on average, for a smaller region. Creating regional buffers, utilizing statistical forecasting, from which goods can be pulled and signal a need for new production, between end consumers and producers is essential to any sort of economic planning.46

In order to concretely make use of these ideas Goldratt offers Five Focusing Steps for Continuous Improvement:

- Find the bottleneck.

- Get more from the bottleneck’s current resources.

- Redirect existing resources towards the bottleneck, don’t produce more than it can or you’ll build up inventory.

- Increase resources for the bottleneck ONLY once you’ve squeezed the most you can out of it.

- Find the new constraint and return to step 1, consider increasing resources to other areas to match the bottleneck’s improvement.47

It is worth noting that the essential idea behind the Theory of Constraints was identified over half a century before Goldratt wrote The Goal by a revolutionary Marxist. Physician and economist Alexander Bogdanov, a founder of the Soviet Proletarian Culture movement called the basic principle the “Law of the Least” in his Magnum Opus Tektology. Tektology is often hailed as a precursor or forerunner of Cybernetics and General Systems Theory. Bogdanov warned of many of the problems that the Soviet economic system developed using Tektology.48

It isn’t hard to see how, for instance, the Stakhanovist movement’s emphasis on exceeding plan targets and creating local optima would undermine overall efficiency in the Soviet planned economy. The Stakhanovist movement was an attempt by Soviet authorities to encourage ‘breaking through’ limits on production by promoting intensified labor and using ‘shock brigades’ to rapidly improve production output. Not only did this provoke organic resistance, deemed by the Soviet authorities to be ‘sabotage’, but even where it was successful, managers complained of the disruption and chaos it caused.49 Stakhanovism created swings of overproduction and shortages, shoddier goods, and ultimately delayed progress in industrialization. Taylorism, though in its Soviet form more pro-worker than in its American form, also caused economic dysfunctions for the same reason. This doesn’t mean that time and motion studies, scientific approaches to specific work processes, and so on are worthless. Scientific approaches to labor are important to improve the ergonomics of work and to objectively evaluate and monitor the process. Further, as the production system improves the bottleneck in a system will shift. The improvement of production is a continuous process. Eventually output may come to saturate demand/need and at this point the bottleneck can serve to stabilize the system and act as a ‘drum beat’ setting the pace of throughput.

Despite his unoriginality, Goldratt’s work remains valuable because his form of exposition is very accessible and it demonstrates that the same invariant objective laws were independently discovered. The more singular and original a theory is, the more suspicious we ought to be, while the more it is obvious given the same starting place, the more likely it is to be true on some level. Goldratt’s theory, like Shewhart’s, gives us a generic scientific framework that doesn’t require domination by an authoritarian managerial strata. Though he assumes that it’s a plant manager who will implement scientific reforms, it doesn’t have to be. A workers’ committee trained and advised by their comrade statisticians, accountants, and engineers can design and implement the improvement toward global optima just as well as a clique of white collar professionals. Bogdanov’s work on the cultural revolution and the need to overcome the capitalist atomized division of labor in favor of collective organization of production remains as relevant as ever as a necessary addition.

Without using the word “Lean” we have explored several of the ideas key to the Lean theoretical framework. Many leftists like Michael Yates in Work Work Work: Labor, Alienation, and Class Struggle, and Kim Moody in Why it’s high time to move on from ‘just-in-time’ supply chains, to use two authors I deeply respect, misunderstand the nature of Lean theories like Kaizen and Just-in-time. This isn’t to say their work isn’t valuable in documenting the real intensification of labor exploitation, abuses of workers, and trends in contemporary capitalism. Yates for his part mistakenly conflates Kaizen with speedups. He says, “what makes kaizen so insidious is that it is never-ending. It is simply a continuous work-intensification scheme camouflaged as something more benign, namely that workers are empowered by it.”50 Subjectively, the experience of a Kaizen exercise on the line may be similar to a speedup because the job gets measurably harder. However, the purpose of Kaizen is not to produce more goods in a shorter amount of time. The goal is to reduce slack in the work unit to deliberately cause the system to break. This allows problems to ‘surface’ that would otherwise have been hidden by the organic desire of workers to successfully do their jobs and meet targets. A Kaizen implementation may involve providing fewer tools or potentially speeding a particular process up, but these are not goals in themselves. If done well, the workers on the line will be actively included in the planning, investigation, and creative side of the Kaizen process but all too often it is done in a technocratic fashion. Yates does acknowledge the purpose of Kaizen in identifying problems, but falsely claims that shutting down the line is discouraged. He goes on to conflate tech companies spending frivolously on the comfort of their programmers to induce them to stay for longer hours with Lean. Ultimately, Yates confuses the exploitation of surplus labor which all workers in capitalist firms experience regardless of organizational forms with the subjective experience of stress and alienation produced by managers.

For Kim Moody’s part, they make the easy error of seeing just-in-time as being about cutting everything to the bone and delivering things at the last second. Yet buffer management is crucial to just-in-time as developed in Japanese firms like Toyota. What the concept actually describes is not over-producing and accumulating huge warehouses of inventory. Prior to just-in-time, capitalist firms would create huge gluts of overproduced goods because they believed that they simply had to market the commodities they made, and they had to produce more and more to increase profit. This philosophy extended inside of the plant and companies like Ford would produce decades worth of parts for cars that would soon be out of date. The goal of just-in-time is not to make supply chains brittle, but to ensure that production is for real demand. Moody says that JIT, “forced its way down every supply chain until each supplier, big or small, was expected to deliver products promptly to the next buyer. This increased competition between companies to deliver goods quickly, which meant firms reduced their costs (usually the price of labour).”51 But just-in-time isn’t about delivering things faster, it is just as often about delivering them slower. Instead of overloading downstream production with product, only delivering what they actually need is the goal. That doesn’t mean that the slogan of just-in-time hasn’t been used as cover by unscrupulous executives to cut costs, lower wages, and place burdens onto workers, but these are what capitalists always work towards. Overworked labor doesn’t deliver goods faster in the long run as Amazon’s internal memos stating they’ve destroyed their own labor supply demonstrate.52

Authors like Yates and Moody do not show how despite the measurable differences between the production theories of the Victorian capitalists and contemporary corporate planners it is ostensibly contemporary production theories and techniques that are the cause of overwork. In both periods we see the same inexorable trends. Their accounts remain very unclear as to why capitalist life in the west looked so different in the post WWII decades despite the greater prevalence of Taylorist methods. I maintain that the common denominator in setting the conditions of work is the class struggle and union power. Labor conditions under ‘Fordist’ and Taylorist capitalism were initially horrific, but without changing any of the underlying logic of the forces of production, workers won enormous gains in both wages and conditions through class struggle. They even bent the science of work to their own favor with the help of experts like Van Kleeck and Polakov. This doesn’t mean Fordist economic logic or contemporary ‘Lean’ global capitalism are a fit basis of communist production. But it is necessary to really understand the scientific kernel of industrial production if we are going to reconfigure production to meet new goals other than profit.

There are limits to Lean, the ‘Total Quality Movement’, and earlier scientific approaches to production. They cannot transcend the need for democratic control over production. We need to have collective social control over setting priorities. This is not a solved problem. To make socialism scientific means to do the hard work of studying and applying the sciences that explain the laws of social systems. But we must also make this science socialist; not by subjecting ideas to ideological purity tests, but by working together and uniting our experiences. There will always be people who have devoted far more time and resources to mastering a discipline and their expertise should be respected. But expertise isn’t enough to make effective decisions for collective problems. We need democratic and comradely means of utilizing science to organize meeting social goals. This is true both in communism and within the communist movement. It isn’t a foregone conclusion that these relations will emerge in the class struggle. They must be fostered and merged with the class struggle movement.

- Marx, K. (2004). Capital: volume I (Vol. 1). Penguin UK.

- Ibid.

- Drucker, Peter F. The essential drucker. Routledge, 2020.

- Malm, A. (2016). Fossil capital: The rise of steam power and the roots of global warming. Verso Books.

- Clark, Gregory. 2010. “The Macroeconomic Aggregates for England, 1209-2008.” Research in Economic History, 27, 51-140.

- Zabihian, F. (2021). Power Plant Engineering. United States: CRC Press.

- Wrege, Charles D., and Anne Marie Stotka. “Cooke creates a classic: The story behind FW Taylor’s principles of scientific management.” Academy of Management Review 3.4 (1978): 736-749.

- Taylor, Frederick Winslow. The principles of scientific management. Harper & brothers, 1919.

- Ibid.

- Braverman, Harry. Labor and monopoly capital: The degradation of work in the twentieth century. NYU Press, 1998.

- Taylor, F. W. (1926). Testimony of Frederick W. Taylor at Hearings Before Special Committee of the House of Representatives, January, 1912: A Classic of Management Literature Reprinted in Full from a Rare Public Document. United States: Taylor Society.

- Taylor, 1919.

- Braverman, 1998.

- Marx, K. (2005). Grundrisse: Foundations of the critique of political economy. Penguin UK.

- Ibid; Engels, F. (1959). Anti-Dühring: Herr Dühring’s Revolution in Science. Russia: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

- https://cosmonautmag.com/2021/01/materialist-history-or-critical-history-a-reply-to-jean-allen/.

- Owen, R. (1817). Essays on the Formation of the Human Character. Longman, Hurst, Rees.

- Nyland, Chris, Kyle Bruce, and Prue Burns. “Taylorism, the International Labour Organization, and the genesis and diffusion of codetermination.” Organization Studies 35.8 (2014): 1149-1169.

- Gantt, Henry Laurence. Work, wages, and profits. Engineering magazine, 1913.

- Gantt, Henry Laurence. Organizing for work. Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1919.

- Kelly, Diana. The Red Taylorist: The Life and Times of Walter Nicholas Polakov. Emerald Group Publishing, 2020.

- Polakov, Walter Nicholas. Man and his affairs from the engineering point of view. Williams & Wilkins, 1925.

- Ibid.

- Kelly, 2020.

- Alchon, G. (1991). Mary van Kleeck and social-economic planning. journal of Policy History, 3(1), 1-23.

- “Remarks of Mary Van Kleeck”, December 4, 1924.

- Alchon, Guy, Mary Van Kleeck and Scientific Management. A Mental Revolution: Scientific Management since Taylor. Ohio State University Press, 1992.

- Selmi, Patrick, and Richard Hunter. “Beyond the Rank and File movement: Mary van Kleeck and social work radicalism in the Great Depression, 1931-1942.” J. Soc. & Soc. Welfare 28 (2001): 75.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Gertner, J. (2012). The idea factory: Bell Labs and the great age of American innovation. Penguin.

- Adams, S. B., Butler, O. R. (1999). Manufacturing the Future: A History of Western Electric. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Deming, W.E. (1967). Walter A. Shewhart, 1891–1967. American Statistician 21:39–40.

- Adams & Butler, 1999.

- Schönsleben, P., Jacobson, B. O., Schmid, S. R. (2011). Integral Logistics Management: Operations and Supply Chain Management Within and Across Companies, Fourth Edition. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- Iswanto, A. H. (2020). Organizational Change Through Lean Methodologies: A Guide for Successful Implementation. United States: Taylor & Francis.

- Hutchins, D. (1983). Quality circles in context. Industrial and Commercial Training, 15(3), 80-82.

- Hackman, J. Richard, and Ruth Wageman. “Total quality management: Empirical, conceptual, and practical issues.” Administrative science quarterly (1995): 309-342.

- Hill, S. (1991). Why quality circles failed but total quality management might succeed. British journal of industrial relations, 29(4), 541-568.

- Prakas Majumdar, J., & Murali Manohar, B. (2011). How to make quality circle a success in manufacturing industries. Asian Journal on Quality, 12(3), 244-253.

- Knouse, S. B., Carson, P. P., Carson, K. D., & Heady, R. B. (2009). Improve constantly and forever: The influence of W. Edwards Deming into the twenty‐first century. The TQM journal, 21(5), 449-461.

- Deming, W. E. (2012). The Essential Deming: Leadership Principles from the Father of Quality. United States: McGraw Hill LLC.

- Kondo, Y. (1994). Kaoru Ishikawa: What he thought and achieved, a basis for further research. Quality Management Journal, 1(4), 86-90.

- Butman, J. (1997). Juran: a lifetime of influence. Germany: Wiley.

- Goldratt-Ashlag, E., Goldratt, E. M. (2023). The Choice. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Limited.

- Goldratt, E. M., Cox, J. (2016). The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- Ibid.

- Bogdanov, A. (1980). Essays in Tektology. United States: Intersystems Publications

- Davies, R. W., & Khlevnyuk, O. (2002). Stakhanovism and the Soviet Economy. Europe-Asia Studies, 54(6), 867–903. http://www.jstor.org/stable/826287.

- Yates, M. D. (2022). Work Work Work: Labor, Alienation, and Class Struggle. United States: Monthly Review Press.

- Moody, K. Why It’s High Time to Move on from ‘Just-In-Time’ Supply Chains. 11 October 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/oct/11/just-in-time-supply-chains-logistical-capitalism.

- Del Rey, J. (2022). Leaked Amazon memo warns the company is running out of people to hire. Vox https://www. vox. com/recode/23170900/leaked-amazon-memo-warehouses-hiring-shortage.