For its seventieth anniversary, Hank Kennedy reflects on the history and legacy of Elia Kazan’s classic trade union-themed crime drama ‘On the Waterfront.’

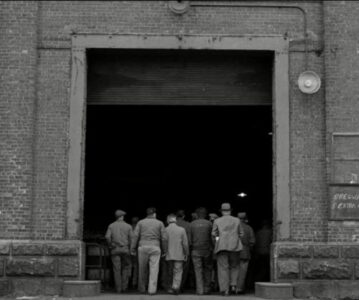

Still from ‘On the Waterfront’ (1954)

“You don’t understand, I could have had class. I could have been a contender. I could have been somebody… instead of a bum, which is what I am, let’s face it.”

Marlon Brando’s monologue in On the Waterfront has passed into the canon of US film. Brando won an Oscar for his role as Terry Malloy – an ex-boxer torn between loyalty to his corrupt, gangster-dominated union (which included his brother Charley, played by Rod Steiger), and his desire to do the right thing. In the film, Terry must make a choice: whether to inform the waterfront crime commission of the abuses and murders he’s witnessed, or to stay silent about what he has seen happening on the docks. Prodded by Father Barry (Karl Malden) and Edie Doyle (Eva Marie Sainte), the sister of his late friend, Terry faces down murderous gangster Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb) and “spills his guts” to the authorities. When Friendly and his goons mercilessly beat Terry on the docks, it looks as though the stevedore is down for the count. Urged on by Barry and Edie, Terry recovers and leads his fellow workers to work, in defiance of Friendly. The story of the making of the film is just as interesting as the film itself. Additionally, On the Waterfront, like many works of art, has a poignant message beneath the gritty surface. For the film’s 70th anniversary, let us retrospect – on the film’s history broadly, and specifically on why its allegories for HUAC and the Hollywood Blacklist make uneasy viewing for leftists today.

The Rise and Fall of The Hook

The story of On the Waterfront has its roots in the grisly, real life murder of union reformer Pete Panto. Panto was an Italian-American dockworker who attempted to depose the corrupt leader of the International Longshoreman’s Association (ILA), Joseph P. Ryan. Panto led mass meetings deploring his undemocratic union local, ILA 929. Mob-run longshore locals would require tribute and kickbacks from members in order for them to receive work; workers who didn’t pay tribute would find themselves unemployed. On the evening of July 14th, 1939, Panto disappeared; afterward, his allies in the union began painting their message, “Dove Pete Panto” in an attempt to find answers. The one they got was horrifying. His body was discovered eighteen months later, in a canvas sack that had been buried on a chicken farm in New Jersey. He had been strangled to death.

Writer Arthur Miller was intrigued by the graffiti referencing Panto. He wrote the script The Hook, a story following a dissident dockworker – modeled on Panto – attempting to clean up his corrupt union. He offered it to Elia Kazan, a director who had previously directed an adaptation of Miller’s Death of a Salesman. The two approached Harry Cohn at Columbia Pictures to produce the film. Cohn was an unlikely producer for any film with a social message. He was the most dictatorial of all the studio heads in Old Hollywood, and not hyperbolically – Cohn produced a flattering documentary about Benito Mussolini, visited the Italian dictator, and kept a signed portrait of him on his desk before, during, and after World War II. Cohn’s desk was thirty feet from his office door. The walk to his desk was described in Hollywood as “the Last Mile,” alluding to the trek the condemned are forced to make before an execution. There was a psychological reason for the distance. Cohn was quoted as saying, “by the time they walk to my desk, they’re beaten.”1

Kazan’s own appraisal of Cohn was that “he enjoyed being Harry Cohn; he liked being the biggest bug on the manure pile.”2 Any hopes that Cohn would produce The Hook were dashed when he showed the film to Roy Brewer, the Hollywood representative of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE). Brewer claimed that no union in the American Federation of Labor (AFL), to which both the ILA and IATSE were affiliated, would have anything to do with dishonesty or gangsters. As a resolute anti-communist, Brewer thought that movies should be going after Marxists, not mobsters.

Of course, when Brewer said that no AFL union would have dealings with gangsters, he was protesting too much. Aside from the ILA, his own union had been dominated by gangsters for most of the 1930s. Mob strongman Willie Bioff ran IATSE with president George Browne. Bioff and Browne together negotiated sweetheart contracts with the major studios – in exchange for payoffs, Bioff and Browne would limit strikes and the union’s demands. Browne said the studios were so eager for labor peace that the routine was “like taking candy from babies.”3 The shakedown wasn’t entirely harmful to the studios either; in sworn statements, executives stated that Bioff and Browne’s scheme saved the studios $15 million dollars in reduced wages.4

After Bioff was convicted of extorting the film studios and removed from his position in IATSE, he was succeeded by Brewer. Browne was likewise replaced, but there was no great shakeup in IATSE. All seven members of the executive board of the international union who served with Browne in 1940 were still there in 1946. This is to say that when Brewer said no AFL union dealt with gangsters, he was lying. Brewer was probably less concerned about telling the truth to Cohn than he was about how The Hook would affect the reputation of his longtime friend, Joseph P. Ryan.

Miller was given a choice by Brewer to salvage the film. Brewer told him that if The Hook was rewritten “so that instead of racketeers terrorizing the dockworkers it would be the Communists” everything would be fine.5 Miller thought that was ridiculous. There were few Communists on the east coast docks and they certainly didn’t run the ILA.6 Indeed, Communists had published a pamphlet about Panto’s murder, criticizing the lack of any meaningful investigation.7 With the obstruction of Cohn and Browne, The Hook died a quiet death in 1951.

Schulberg Steps In

The ILA leadership, however, was still featuring prominently in the news. New York Sun reporter Malcolm Johnson won a Pulitzer Prize in 1949 for his series on the incestuous relationship between the union and the underworld, reporting that Joseph P. Ryan hobnobbed with both gangsters and powerful political figures such as then-governor of New York Franklin Roosevelt, New York mayor Jimmy Walker, and Jersey City mayor Frank Hague. Ryan, like George Browne, was a notorious trade union red-baiter who routinely accused his critics of communist sympathies. Ryan employed numerous strongarm men to keep order, with the knowledge and acquiescence of the shipping companies – one company official supported the hiring of noted criminals because they would “keep the men in line and get the maximum work out of them. They’ll be afraid of him.”8

Screenwriter Budd Schulberg was a reader of Johnson’s series and used the real-life stories as an inspiration for the screenplay that became On the Waterfront. Schulberg’s screenplay has a similar premise to The Hook, although he claimed to have never read it while working on his own screenplay. There is one clear difference: the presence of informing on the gangsters to the waterfront crime commission as a plot device. Informing was included as a result of drastic real-life challenges facing Hollywood in the form of the Red Scare and the Blacklist.

Ex-communists Kazan and Schulberg both testified as friendly witnesses before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC); Shulberg in 1951, and Kazan in 1952. Schulberg was not forced to testify; he sent a telegram asking to testify after being labeled a communist by writer Richard Collins. Schulberg had been a member of the Communist Party for a few years, but left over the reception to his novel What Makes Sammy Run. Schulberg’s novel focuses on Sammy Glick, a grasping, backstabbing Jewish screenwriter who rises to the top of the Hollywood heap. The novel first received praise from the Party press,9 but the same reviewer was forced to publicly recant his earlier review.10 The Party leadership had determined that the novel contributed to an atmosphere of anti-Semitism and failed to heroicize the Hollywood trade unions. Therefore, it had to be condemned.11

In his written explanation for naming names Schulberg claimed that “art must always wither and die when it comes under the control of any censorship that judges a writer by his willingness to conform.”12 Schulberg saw no irony in fighting Soviet communism with methods that were sure to lead to censorship and conformity in art (the same problems he had with American communists). It seems rather likely that personal vengeance from his treatment over What Makes Sammy Run determined his choice.

Kazan was equally unapologetic about informing before HUAC. He appeared before the committee twice in 1952, naming fifteen names from his two-year stretch within the Communist Party. Afterwards, Kazan placed an advertisement in the New York Times asking those who knew anything about communist activity, such as names of Communist Party members, to “make them known, either to the public or to the appropriate Government agency.” Given the prevalent Hollywood Blacklist, anyone named by Schulberg or Kazan was in danger of having their careers or lives destroyed. Nor were Schulberg or Kazan in any danger themselves; the two of them could have found work writing and directing for theater, which maintained no such blacklist.

Additionally, several performers died as an indirect result of the Blacklist. Actors John Garfield and Canada Lee both died of heart attacks, certainly hastened by the harassment of HUAC. Phillip Loeb committed suicide via sleeping pills after he was dropped from the television show The Goldbergs due to his alleged Communist affiliations. When actress Mady Christians died of a cerebral hemorrhage, playwright Elmer Rice stated it was “hastened, if not actually caused, by the small-souled witch hunters who make a fine art of character assassination.” Actor J. Edward Bromberg, posthumously named by Kazan, died of a heart attack in 1951 at 47. Playwright Clifford Odets termed it “death by political misadventure.”13

In the aftermath of Kazan’s testimony, Schulberg approached him about working together. One potential idea was the script Schulberg had been working on about corruption on the docks, at this point called Crime on the Waterfront. Given that both Kazan and Schulberg had cooperated with HUAC, there could be no accusations from the Harry Cohns and Roy Brewers of the film world that they were “soft” on Communists. With the backing of independent producer Sam Spiegel, they entered production of a film – eventually rechristened On the Waterfront.

The Undercover Theme of On the Waterfront

On the Waterfront is not effective if it was meant as an expose of gangster control of labor. There is little sense of labor racketeering as a social problem. One dockworker explains that “the waterfront… ain’t part of America.” The heroic priest Father Barry states that “no other union in the country would stand for” the violence and corruption of the longshore union. But Barry was incorrect – aside from the ILA and IATSE, Americans were about to be introduced to a labor union who became a shorthand for crime and racketeering: the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. During the 1957-1959 televised McClellan Committee hearings, viewers met colorful gangsters who doubled as Teamsters, such as Joey Glimco, Johnny Dio, and Tony Provenzano. It was difficult to tell where la cosa nostra ended and the Teamsters began.

This lack of accuracy continues in the treatment of management. Michael Parenti points out “not a critical word is uttered against the owners, even though they had a real-life history of collaborating with union racketeers.”14 Sociologist Daniel Bell concluded in 1959 that labor racketeering on the docks served a useful function for management. He wrote, “industrial racketeering, however, performs the function at a high price—which other agencies cannot do, of stabilizing a chaotic market and establishing an order and structure in the industry.”15 In the film, management observes the fight between Johnny Friendly’s goons and Terry impassively. They don’t care who runs the union, so long as the work gets done. Outside the silver screen, though, management would much prefer a corrupt, undemocratic union to a militant, democratic one.

If the text of On the Waterfront falls short, the film shines in the subtext. Schulberg and Kazan crafted a total rehabilitation of the informer, an archetype of disrepute in film since John Ford’s The Informer. The creators stack the narrative deck in every conceivable way to make informing the only moral choice, even at the cost of dramatic tension. When Friendly’s hoods kill the protagonist’s brother, Charley, that eliminates the stakes in Terry’s testimony. With his brother dead, who is Terry really ratting on? The only named hoodlum left is Friendly, a snarling, brutal killer. The choice to inform on him is hardly a choice at all.

Another example of this deck-stacking is in the treatment of the investigators. HUAC was made a permanent committee at the behest of Congressman John Rankin, a notorious bigot and ally of Christian Nationalist Gerald L.K. Smith. The investigators in On the Waterfront, by contrast, couldn’t be more helpful and polite. They tell Terry “you have every right not to talk if that’s what you choose to do” and “you can have a lawyer if you wish, and you’re privileged under the Constitution to refuse to answer questions that may implicate you in any crime.” Quite the change from the badgering investigators of HUAC.

Legacy and Endurance

If the politics of On the Waterfront are so bad, what accounts for its endurance? Noam Chomsky, in Understanding Power, thought he found the answer. Chomsky claimed, “On the Waterfront became a huge hit — because it was anti-union.” Chomsky may be a fine linguist and political commentator, but he proved himself to be no film critic or historian. In fact, the famous anarchist is virtually repeating the views of Communist screenwriter John Howard Lawson, who saw the film as “anti-democratic, anti-labor, and anti-human propaganda.”16 On the Waterfront has faults, but being anti-union is not one of them. If On the Waterfront is said to be anti-union, what of activists in the United Mineworkers, Teamsters, or UAW who fought to clean up their unions? Are they likewise anti-union?

It’s much more likely that On the Waterfront has endured due to its streetwise dialogue and its stunning cast, including stars like Brando (himself uncomfortable with Kazan’s informing saying he knew people “who had been deeply hurt” by HUAC),17 Rod Stieger, Eva Marie Saint (in her film debut!), and character actors like Karl Malden and Lee J. Cobb. The film also benefits from the emotional score by Leonard Bernstein, his only film work. Then there’s the then-novel decision to shoot the film on location for greater authenticity, rather than on a soundstage in Hollywood. Of course, the film is also notable for being one of the few to focus on working class life, despite the political baggage it carries with it.

The fading of HUAC and the Hollywood Blacklist from popular memory may also play a part, paradoxically, in the film’s continuing appeal. Writer Glenn Frankel makes the intriguing argument that On the Waterfront could be a companion piece to High Noon.18 High Noon was meant by screenwriter Carl Foreman as an allegory for refusing to inform HUAC, the opposite message of On the Waterfront. But the two have some similarities; Frankel writes that “both are about brave men who, when abandoned by friends and allies, choose to stand alone against evil forces and triumph.”19

Throughout his life, Kazan never apologized for informing HUAC: “When critics say that I put my story and my feelings on the screen, to justify my informing, they are right.” Kazan wrote in his autobiography, “On the Waterfront was my own story; every day I worked on that film, I was telling the world where I stood…”20 He was never forgiven for informing, either. Blacklisted actor Zero Mostel tagged him as “Looselips.” Tony Krabner, named as a Communist by Kazan, alleged that Kazan had named names in exchange for a $500,000 contract from the major studios, a charge that Kazan always denied. Abraham Polonsky, the man behind the film noir classics Body and Soul and Force of Evil, declared that the only award Kazan should have received was the “Benedict Arnold award.”

Despite Polonsky’s complaints and socialist criticism like this article, the legacy of On the Waterfront seems secure as the film enters its seventh decade. Still, it’s worth wondering what could have happened if The Hook had been produced instead. That script dealt with the realities of working-class life at a time when it was not popular in film to do so, as did On the Waterfront. It took the side of rank-and-file workers against a corrupt, entrenched union leadership. So did Kazan’s film. But beyond these similarities are more differences.

In The Hook, protagonist Marty tries to clean up the union by running for local office himself. He inspires a layer of rank-and-file activists to try to take the union into their own hands. In a speech to his fellow longshoremen, Marty lamented, “You know why we got no democracy in this here union? Because you guys do not care. How many of youse come to our meeting? Six? Seven? There’s nearly seven hundred in this here local.” Marty ultimately loses his race for union president, but gives every indication that he will fight on until the workers finally get the decent leadership they deserve. Contrast this with On the Waterfront, which implies that things for the union will be fine once the state has stepped in to clean things up.

In 2015, The Hook appeared as a stage production in the UK, giving audiences an opportunity to see what Miller’s unrealized film could have been. The Guardian opined that the play’s “subject matter has lost its bite.” Given the declines in workers rights, workplace safety, and a decline in real wages, how can that be the case? If anything, it’s The Hook that is relevant – not Elia Kazan’s apologia for his own guilty conscience.

- Neal Gabler, An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood (New York: Anchor Books, 1989), 153.

- Bob Thomas, King Cohn: The Life and Times of Harry Cohn (New York: G.P, Putnam’s Sons, 1967), xviii-xvix.

- Dan E. Moldea, Dark Victory: Ronald Reagan, MCA, and the Mob (New York: Penguin, 1986), 27.

- David Caute, The Great Fear: The Anti Communist Purge Under Truman and Eisenhower (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978), 488.

- Nora Sayre, Running Time: Films of the Cold War (New York: the Dial Press, 1982), 153.

- Hollywood did eventually make a film assailing a supposed Communist control of the docks in the West Coast-set The Woman on Pier 13 (a.k.a. I Married a Communist). The Communists in that film act just like gangsters, even throwing an informer off the docks to drown. Suffice it to say that Miller was not involved with The Woman on Pier 13.

- Michael Singer, “The Kefauver Committee and the Pete Panto Murder,” Freedom of the Press Co., Inc. (1951) https://digital.library.pitt.edu/islandora/object/pitt%3A31735061540385/viewer#page/16/mode/1up

- Charles P. Larrowe, Shape Up and Hiring Hall (Berkley: University of California Press, 1955), 19.

- Charles Glenn, “Novel—The Story of a Hollywood Heel,” Daily People’s World, April 2, 1941.

- Charles Glenn “Hollywood Vine” Daily People’s World April 24, 1941

- Victor S. Navasky, Naming Names (New York: Hill and Wang, 2003), 239-240.

- Budd Schulberg, “Collision With the Party Line,” Saturday Review, August 30, 1952.

- Otto Friedrich, City of Nets: A Portrait of Hollywood in the 1940s (New York: Harper and Row, 1986), 382.

- Michael Parenti, Make Believe Media: The Politics of Entertainment (New York: St, Martin’s Press, 1992), 79.

- Daniel Bell, “The Racket Ridden Longshoremen,” Dissent, Autumn, 1959.

- John Howard Lawson, “Hollywood on the Waterfront: Union Leaders Are Gangsters, Workers Are Helpless,” Hollywood Review, Nov./Dec. 1954.

- Marlon Brando and Robert Lindsey, Songs My Mother Taught Me (New York: Random House, 1994), 194.

- Glenn Frankel, High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic (New York: Bloomsbury, 2017), 260.

- Ibid.

- Elia Kazan, Kazan: A Life (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1988), 500.