Sophia Homa provides some historical context for a classic Soviet film to celebrate the Nazi surrender in World War II.

Today is the 9th of May, also known as Victory Day, a holiday that celebrates the surrender of Nazi Germany. In good Cold War fashion, it is traditionally celebrated on May 8th in the Western Allied countries while in former Soviet bloc countries – since the surrender took place after midnight Moscow time – on May 9th.

Released in January 1950, The Fall of Berlin came out just 5 years after the end of World War II (or the Great Patriotic War). This was a mere 3 years before the death of Stalin – although, of course, nobody knew that at the time.

The movie, clocking in at over two-and-a-half hours, begins just before the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II and proceeds through to, you guessed it, the fall of Berlin. The magisterial film centers two idealized Soviet citizens, Alexei Ivanov and Natasha Rumyantseva, yet also provides a fly-on-the-wall view of Soviet and Nazi heads of state, even entering Hitler’s infamous bunker. Here are 10 things you might miss watching The Fall of Berlin.

This is no ordinary score

The score was done by Dmitri Shostakovich. If you hear notes which seem familiar the score is reminiscent of another work of his, Symphony No. 7 aka Leningrad. Written during and about the terrible Siege of Leningrad, it was famously blared over loudspeakers at the besieging Nazi armies in a show of defiance. This moving piece memorializes and seeks to encapsulate the siege’s horrors and heroism as combined Nazi and Finnish forces attempted to make a new Carthage of the symbolic city at the heart of the October Revolution and communist experiment. It was an instant classic and was played for years as a tribute to the sacrifice of those who held out and fought for life against the death cult of fascism.

Listen to Leningrad free on YouTube here.

For Further Reading: Symphony for the City of the Dead: Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad by M. T. Anderson.

Alyosha isn’t just a hard worker – he’s a Stakhanovite worker

When we first meet Alyosha he is a Stakhanovite worker who has just broken a new steel production record, resulting in both him and his manager being awarded. Stakhanovite workers were both a PR campaign and a genuine grassroots movement within the Soviet Union where workers went above and beyond their quotas as outlined within the Five Year Plans. The Stakhanovite movement reflected a desire to speed up the accumulation of productive forces in the woefully underdeveloped Soviet Union and was eagerly given a platform by the state apparatus as a tool for managers to engage in workplace speed up. Stakhanovite workers were lionized in the press as heroes and could become celebrities.

For a non-war movie focusing on a Stakhanovite worker, I recommend the Polish 1977 film Man of Marble.

Many of Natasha’s students are Young Pioneers

When we first meet Natasha she is an idealistic teacher leading her students on a field trip. Viewers will notice that many of her students are wearing red neckerchiefs. This isn’t merely a fashion choice – it codes them as members of the Young Pioneer organization. A series of organizations came into existence during the revolutionary upheaval of Russia. Part of a global trend in the flowering of youth organizations such as the Scouting movement, there coalesced into three main organizations based on age: Little Octobrists for very young children, Young Pioneers for 10-14-year-olds, and then finally the Young Communist League, more commonly known as the Komsomol.

In the Soviet context, common tropes of youth embodying vigor and hope took on even greater importance. In this new type of society, education and youth organization were key arenas for the socialization of young people and the creation of a New Soviet Man. Komsomol members were seen as the future vanguard who would build communism, the most forward-thinking youth. To see a teacher leading a classroom made up mostly of Young Pioneers would have registered as immensely symbolic for a hopeful future.

For more information on this topic, listen to this episode of Sean’s Russia Blog on the Komsomol youth organization: Communism, Youth, and Generation.

Natasha recreates a famous Women’s Day Poster

During her field trip, Natasha is tasked by the local plant manager with giving a speech to recognize Alyosha for his achievements in exceeding production quotas. Her impassioned speech extolling Alyosha’s virtues as a worker is surpassed only by her zealous praise for Comrade Stalin who made all of this possible. At the podium she becomes a tableau, reenacting a 1947 International Working Women’s Day poster, all under the kindly gaze of a huge Stalin painting.

Before its wider adoption by second wave feminists beginning in the 1960s, International Working Women’s Day was primarily a socialist and communist holiday. Mirroring the history of May Day and other ‘invented traditions’ as a socialist counter-culture developed, IWWD arose in the early 1900s as a focal point in popularizing the struggle for women’s rights. It initially lacked a fixed date and in America was often celebrated on the final Sunday of February to allow for mass meetings. On February 23rd 1917 (Russian Calendar) which was March 8th in the Western calendar, Russian women organized a Women’s Day strike and demonstration which broke out into a rebellion and ignited the February Revolution, toppling the Tsar within a week. After the October Revolution later that year, March 8th was made an official holiday to pin Women’s Day to the commemoration of the heroic women’s struggle of 1917.

For Further Reading: On the Socialist Origins of International Women’s Day, JSTOR

Also check out the Cosmonaut publication of a report on the 1910 Second International Socialist Congress of Women which adopted Clara Zetkin’s proposal to officially organize an annual Women’s Day.

Alyosha’s meaningful shirt

Alyosha walks Natasha home that night after her speech and so their courtship begins. We see them on a date walking through enormous, billowing wheat fields. As a demonstration of this model worker’s origins in sturdy peasant stock he wears a kosovorotka, a peasant-style shirt that was a favorite garment of Nikolai Bukharin. Unfortunately for the new couple, their idyllic date is abruptly brought to an end as a Nazi blitzkrieg begins bombing the town.

Nazis’ Use of Slave Labor

Alyosha wakes up in the hospital to learn that the Germans have made huge inroads into Soviet territory. Natasha is missing, kidnapped, and taken deep into Nazi territory as part of a slave labor force.

Forced labor under the Nazi regime is often under-emphasized in American historical memory. Where it is discussed, typically the enslavement of Jews is at the fore such as the movie Schindler’s List, which takes place in Nazi industrialist Oskar Schindler’s forced labor camp. One exception is the classic 1963 movie The Great Escape which does feature a segregated pool of Russian prisoners of war used as a logging slave labor force.

In truth, civilian slave labor (both Jewish and non-Jewish) were increasingly vital to the Nazi economy as the war continued. Beyer & Schneider’s research into forced labor under the Nazis helps to get a sense of the magnitude involved: according to their research at the peak of the war one in every five workers in the Third Reich economy were forced laborers. By some estimates, the Third Reich saw a peak in January 1944 with 10 million forced laborers. Of these, some 5 – 6.5 million were civilians kidnapped and brought within German borders. A vast majority of civilian forced laborers brought to Germany were from Eastern European countries – 65% of the total, with nearly 34% of all forced laborers coming from the USSR.

For Further Reading: Forced Labor under the Third Reich, Beyer & Schneider

The Red Army’s fight choreography is less than stellar

The battle scenes are both impressive yet also quite different from what modern viewers may expect. They are spectacular – it is clear no cost was spared in the making of the movie. Huge tanks roll over snaking trenches, explosions and flames burst forth. But the soldiers are often too busy marching heroically, backs straight and chests out to bother taking cover. Anyone who has played a WWII video game will be familiar with the Soviet PPSh or PPD machine gun and its distinctive drum magazine. What they may not be as familiar with is the tactic displayed in the movie of simply throwing the rifle at a Nazi during trench fighting.

For more information on actual Red Army and partisan tactics during World War II, check out The Partisan’s Handbook on Amazon

The men behind the makeup

The view inside the Nazi High Command is not pretty. Hitler is a twitchy leader wracked with tics and compulsively shouting. Goebbels the Minister of Propaganda is a diminutive, scheming braggart. Goering, the head of the Luftwaffe, is a pompous gourmand whose sumptuous estate is filled with fine wines and treasures. An army of pathetic pencil pushers march in and out sharing increasingly negative memos as the war progresses, submissive peons in a highly hierarchical state. And to top all this off, the Nazis seem to have returned from the worst Sephora ever. Contouring emphasizes wrinkles, eye bags, and other sinister features to an almost campy degree.

A different result of the makeup sponge can be seen on the face of Comrade Stalin. It’s hard to believe botox was not invented yet when watching the General Secretary. He displays perfect salt and pepper hair, a crisp uniform, and a clearly middle-aged-but-not-aging face. He is the perfect comrade/secretary of the Union. Somehow always looking unperturbed even when consulting his inner circle, he patiently listens to them, weighs their reports, and makes decisions he is sure of.

Catholic Complicity (and worse) with Fascism

This movie highlights the troubling relationship between the Catholic Church and fascism. In one scene Archbishop Orsenigo, the Apostolic Nuncio to Germany (basically a diplomat), has an audience with Hitler and tells him the Holy See blesses him and the heroic German armies. It is well-documented that the two popes during the reign of the Nazis, Pope Pius XI and Pope Pius XII, were soft at best on the various fascist governments – commonly chalked up in historiography to favoring appeasement and lending credibility in an attempt to secure Catholics’ safety from the Nazi regime. Yet common anti-communist sympathies between Berlin and Rome are hard to deny, and it is indisputable that there were layers of outright fascist supporters at the top layer of the Church such as Orsenigo – who in this movie looks more like Count Dracula than anything else.

For more information on Vatican collaboration with Fascism, I highly recommend this article outlining the active role the Vatican played in constructing international anti-communist movements in the interwar period and how these campaigns inextricably linked Catholic anti-communism with Nazi/fascist anti-communism in practice.

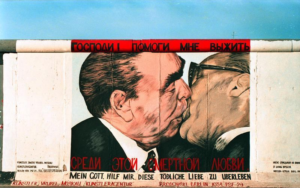

The Socialist fraternal kiss

Several times men kiss each other on the mouth. It is passionate, but Platonic rather than erotic. This is the socialist fraternal kiss. Sometimes on the mouth, sometimes on the cheek, it is a ritual symbolizing fraternity between comrades and was frequently performed in the ‘actually existing socialist’ states. In fact, I counted and we see more instances of men kissing men (via the Socialist fraternal kiss) than we do romantic kisses.

Don’t get any ideas though; we unfortunately cannot claim these scenes or Alyosha as a gay icon. After the Stalinist counter-revolution, queer rights were dramatically rolled back and the nuclear family re-established as a hegemonic social institution to be adhered to. This of course did not stop chauvinistic Cold War propaganda from the West. See the myriad of homophobic rhetoric from Allied so-called progressives deriding the Socialist fraternal kiss as gay. Perhaps worse, this notion has been reborn in a lamer contemporary equivalent: ‘Putin tops Trump, making America weak.’ Not only does this insult bottoms everywhere, it also excludes the possibility of a power bottom.

There you have it, 10 things you might miss watching The Fall of Berlin. An enjoyable movie from start to finish; it promises over two hours of melodrama, optimism for a better world, and best of all: Nazis getting crushed. Sit back, relax, and watch The Fall of Berlin today.

The Fall of Berlin is available for free in two parts on YouTube in Russian with English subtitles: