Renato Flores argues that a grand narrative is needed to unify and mobilize the exploited and oppressed against an exterminist world order.

I

The permanent news cycle paralyzes us. We wait in an anxious manner for the next push notification containing the latest breaking news item. It further spells our doom as a species. We share it on social media, screaming to the void that we are all doomed. We are validated. Tally up a few likes, regain some sanity, and wait for the next notification. International politics is predominantly reduced to a spectator sport and we can only watch in despair at how our side is losing: Bolivia, Corbyn, and the inaction on climate change after the Australian fires. Dreams of Fully Automated Luxury Communism (FALC) remain a fanciful hope for an earthly heaven, and not a practical political program. Instead, utopias are confronted by cruel reality. We are stuck on Spaceship Earth accelerating towards the dystopian future of exterminism outlined in the book Four Futures: neither the overcoming of scarcity nor the conquest of equality.1

Already, the four Horsemen of the Apocalypse appear lined up and ready to head the exterministic state: Trump, Bolsonaro, Modi and Johnson. But these four are far from the final product Capital needs to keep on going, and in some ways are just throwbacks to an older era. For example, Bolsonaro has received wide attention for his role promoting settler-colonialism in the Amazon. But in the Americas, accumulation by dispossession is centuries old and cannot be understood as a new phenomenon. The future state that Capital needs is darker. One that manages a society where there are not enough resources to go around, provided the economic and power structure stays the same. One where climate change and the limits of ecology mean capitalism cannot appropriate Cheap Nature to keep on reinventing itself.2 One where there is a population surplus that must be first pacified and eventually disposed of to ensure the stability of the system.

The combination of falling rates of profit, and a falling capacity to appropriate natural surpluses leads to surplus population. This concept was originally introduced by Marx, and is specific to an economic system. Because Cheap Nature is no longer as cheap, and production is overcapitalized, the wheels of capitalism are stalling. Within this framework, stating that there is a population surplus is simply reframing the fact that labor-power is being (over)produced in such quantities that capital cannot accomodate for a profitable use of it. The wage fund which would correspond to “normal” capitalist operation cannot pay the social reproduction costs. This means that the labor supply must be reduced, that is, the workers must be disposed of.

It is necessary to distinguish the concept of surplus population in an economic system from the Malthusian “overpopulation” argument that has been around for some time. The latter is a thinly-veiled racist red herring that basically states: (1) there are too many people on Earth; (2) we have gone beyond Earth’s carrying capacity, and (3) to return to sustainability we have to drastically reduce the population. This is often done by encouraging poor and racialized people to have less children. Because it is logically simple, distributes the blame equally among all of us, and does not challenge the power structure, it is repeatedly promoted and given intellectual currency. But this argument fails to acknowledge that most damage to the environment is done by a fraction of the world’s population. These people, who mainly reside within the imperial core, unsustainably enjoy what was best theorized by Brand and Wissen as the imperial mode of living.3 The imperial mode of living relies on “the unlimited appropriation of resources, a disproportionate claim to global and local ecosystem sinks, and cheap labor from elsewhere”. If this imperial mode of living were substituted with a more rational and ecologically sound system of food and commodity production, more than enough resources exist on Earth to provide a decent living for all.

With respect to surplus labor, the concept can bend in many directions. In a positive manner it promises freedom from toil. The automation utopians refer to “peak horse”, a real phenomenon: when cars were introduced, fewer horses were needed to draw carts around.4 Because of the declining demand for horse work, their population reached a peak in the early 20th century and declined after. The analogy is drawn to humans: it has become clear that the capitalist system cannot adequately employ large sections of the population, because these sections cannot contribute to profitability. In the global imperial centers, people remain underemployed in jobs which could perfectly be replaced by robots, or even eliminated. With this, the techno-utopians jump at the idea that advances in technology indicate that we have reached “peak humans” needed for production of essential commodities. Automation means that in the future we will need to work less. We will be in a post-scarcity society, and we will find a way of sharing the toils of labor adequately.

What the proponents of FALC fail to consider is that with automation, the surplus population might just as well be ignored or left to die. This is not a future designed by the Malthusian Thanos, the archvillain of the Avengers, who wanted to kill off half of the population selected at random. Instead, it will involve the isolation and elimination of the most vulnerable who no longer serve a purpose. The surplus population in the peripheries keeps on growing, becoming increasingly informalized and displaced from production, and at the same time forced to live in destitute housing, as Mike Davis studies in Planet of Slums. For millions of people, the costs of social reproduction aren’t being met, and they are either relying on the extended family and remittances from abroad, or simply waiting to die. On an individual basis, they can risk their lives to migrate towards the centers of capitalism. But the numbers are insufficient to provide structural relief. “Strong” borders make sure that the surplus population of the global South stays there, so transnational companies can reap the benefits of cheap labor.5

Instead of providing a fully automated future, the state returns to its basic skeleton of coercion and parasitism. And coercion can devolve into getting rid of the nuisance population that demands the means to live, but often has little to fight back with. There are several examples of this happening in history. The prime one is the recent fate of the Palestinians: in the 90s, due to the collapse of the USSR, a large number of Soviet Jews emigrated to Israel. They replaced the Palestinians at the lowest level of the Israeli class pyramid. This was very advantageous to Israeli capitalism, as it substituted cheap Palestinian labor, which had recently engaged in campaigns of civil resistance like strikes and boycotts, for more reliable workers. Palestinians were pushed out of the economy and slowly confined to their open-air prisons, which at the same time severely hurt their ability to engage in nonviolent campaigns.

An objection could be raised: Israel is not just a capitalist state, it is a settler-colonial state which attempts to erase Palestinians. Indeed, watching the working class in the Global North repeatedly vote to protect its privileges, it is tempting to adopt a “third-worldist” approach and deny that these classes are revolutionary at all, and that the potential for revolution lies in the Global South. However, these dynamics are barely contained to the centers of capitalism. Another current example is the role of Black people in Brazil. Brazil is similar to the United States in that it has a large black population directly descended from slaves. After emancipation, they were left in rural areas where opportunities did not abound. They chose to move towards the large cities (a Southward pattern in Brazil). In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, their homes were demolished, and they were forced into neighborhoods full of informal housing: the favelas, which grew steadily during the 20th century. Their inhabitants often worked informal jobs, but as Brazil’s economic situation worsened, they were pushed out of the economy and into progressively worse jobs and even the criminal market. To deal with this, the police are increasingly empowered to indiscriminately enact violence, to deal with crime resulting from these transactions. In a racist society, this results in thousands killed at the hands of the police yearly.

So far, the picture painted does not differ much from the current situation in the United States, where police routinely kill people of color and walk away free. The murder of black councilwoman Marielle Franco is not that different from the murder of Black Lives Matter activists in the United States, if one sets aside the visibility of Marielle. But this would miss the point- more and more the quiet parts are said and acted out loud. Instead of Bolsonaro, who has his hands dirty in Marielle’s murder even if he denies it, we should be looking at another Brazilian politician. Rio governor Wilson Witzel was elected in 2018 on a platform of slaughtering “drug gangsters”. He has basically given carte blanche to the police to shoot on sight, and has proposed shutting down access completely to certain favelas. Witzel does this to wide applause, and it is not hard to imagine his reelection.

In the case of Brazil, racism comes into play, and is weaponized. But there are other examples of exterministic politicians who do not force themselves into office in the Global South, but are elected. One of the most infamous is Filipino president Rodrigo Duterte, who won the national election on a platform of slaughtering “drug-dealers”. Before jumping to the national stage, Duterte was the mayor of the city of Davao, and served seven terms. The emphasis here is placed on the fact that despite being known to command death squads, he was repeatedly re-elected as mayor. Later, he was promoted to the national stage, where he won a national election with 39% of the vote out of an 81% turnout. This is the barbarism which Rosa Luxemburg warned us about, with voters clearly electing barbarism. In the exterministic future which awaits us we will have more figures like Duterte and Witzel, who will openly shoot the increasing number of marginalized people to protect an ever decreasing community of the free who enthusiastically vote for them.

In the United States, the stage is set for something worse than Trump. Frank Rizzo, the police chief-turned-mayor of Philadelphia who supervised the MOVE bombing provides a historical example which was ultimately contained to just a mayoral position. The system produces many Rizzos, as a glance at any police “union” shows. Finding the cracks where stress will first concentrate in the US is not hard. Black and brown communities, both within the US and trying to access it will be prime cannon fodder. One just has to read history, or even the present news, to find that the list of affronts against them is long. However, the way the COVID-19 pandemic is being handled, and the inaction on climate change in the face of the fires in Australia, make it clear that the ruling classes do not care about any of us, and will do nothing to protect us from devastation if it inconveniences the death march of profit. The Climate Leviathan, an authoritarian planetary government led by a liberal consensus to adequately address climate change will never happen.6 The future where many Climate Behemoth states led by populist right-wingers, which simply refuse to deal with the structural problems of ecological destruction and population surplus, are much more likely. We are seeing this around the world, even in the centers of capitalism: rather than address the fires, the prime minister of Australia decided to outlaw climate boycotts. The time of monsters is coming.

II

Faced with this depressing prospect, how do we begin to organize? Postmodernism has repeatedly tried to kill grand narratives, while at the same time claiming the end of history has been reached. The underlying message was that class struggle is off the table. And it worked, for a while. But the house of cards is collapsing. The actually existing left is not prepared for the collapse of capitalism, often stuck in debates on theory that appear very important, but in practice make little difference in how they relate to the working class. Old-time socialists are disoriented as they face a working-class subjected to decades of ideological conditioning. They often forget that this is not the 20th century, and the same propaganda will not work.

We are missing both a unifying ethics of sacrifice and collectivity, and a sense of how merciless and brutal our enemies can be. Until this is regained, the confines of ideology channel rebellion into a simple solution- giving our powers to a terrestrial shaman, through the sacred ritual of the ballot box. The shaman knows how to interface between the world of the commoners and the sacred world of the political. He or she can lead us to salvation if we trust and follow his lead.

The shaman once again comes to ask us for our strength. We need to push him using all our might past the portal to take the sacred altar. Donations are requested, and we open our wallets. The most ardent canvass and phonebank to share the good news of “democratic socialism”. We study Salvador Allende and think, “well this time it could work, the US cannot coup itself?” And even if half the box of oranges is rotten, we believe that the bottom half must be good to eat. Once we get our shaman into office, he will be able to interface between the sacred and the common as long as we keep giving him our powers, delivering us to the utopia. Other kinds of shamans also draw from the collective, but our strength in numbers must be greater. We just need to show it in the ballot box.

But many cannot give their power through the ballot box ritual. And the other, darker shamans do not play fair. They control the tempo of the battle, and can cast their message across time and space much better. After all, the ruling class would rather have a dark shaman who doesn’t threaten its power than a red sorcerer who threatens capitalists profits. Our shaman plays by the rules of the game, and the most destructive weapons end up being unleashed by one side only. Even when backed by messianaic movements, Corbyn played fair, and lost. Sanders played fair in 2016, and also lost. Lula played fair, and was imprisoned to prevent his electoral candidacy. It remains to be seen what will become of the Sanders 2020 campaign, but the box of oranges is looking rotten. The dark shamans are able to weaponize our differences, to persuade others to give them powers. Our powers do not lie in the ballot box or within the constitutional framework at all. Until we achieve a grand narrative which not only includes all of us, the dispossessed, but speaks to all of us too, we are bound to lose again and again. Understanding this involves transcending the shamanistic and legalistic individual view to a collective, religious view of our historic mission of redemption and change.

I would be accused, fairly, of abusing the metaphor when describing the current state of politics. But narratives can be the best way to get a point across. We often make sense of the world around us with the use of metaphors and imaginary creatures. Our fears are often turned into monsters, and fear of monsters provokes hatred. The Right knows how to transform the Other into the monster: the Jew, the immigrant, the Muslim, the black, the LGBTQ… all of them ruining our society. They are deviants and criminals, and once we get rid of them, we will all be more prosperous. This narrative crystallizes a dominant group. It legitimizes the exterminist state, delineating the “us” from the “them”. It propels our bright leader to power not just through the gun but also through the ballot box. Because “they” are sabotaging us, we are not doing as well as we should. And when the left lacks the power to counter this monster-making with its own mythmaking, it can feel immobilized. Coexist stickers are not sufficient to unify a mass, and without a collective vision, as people like Elizabeth Warren are discovering, policy proposals amount to nothing.

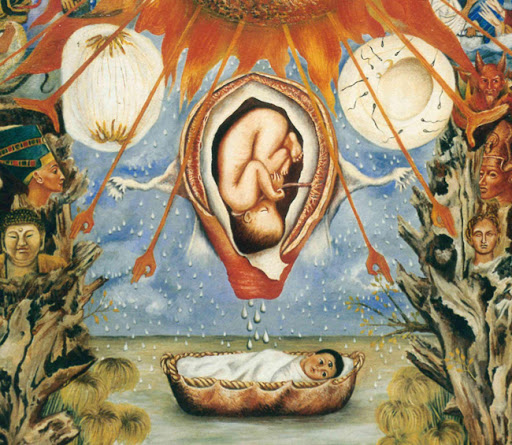

We could try and play the same game of monsters. But the power of demonic imagery in the hands of the dispossessed is somewhat limited unless it is deployed as part of a wider struggle. At its minimum, it serves as a substitution used to relate to capitalism when it becomes something sublime and out of our control. In this disorientation, the structures of power are often reimagined through the imagery of monsters. This has a long history both in England and the Netherlands in the centuries of the ascendant bourgeoise, and has seen use in Haiti through the image of zombie-slaves.7 It is also present in contemporary Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, as each endures massive “structural adjustments” where the commons are privatized.8

Monsters have served as valuable storytelling devices for progressives. Thomas Paine laid bare how the aristocracy was a cannibal system, in which aside from the first-born male everything else was discarded.9 In Frankenstein, the abilities of the new ruling class to lay claim to subaltern bodies and forming a monster provides a metaphor for the new factory system. Even before the Marxist analysis of capitalism, it was clear that the new proletariat of the nineteenth century was something historically distinct. The gothic, understood as the world of the desolate and macabre, was used to efficiently drive the political message home. It is not enough to understand something, dispossession must be felt. The warm strain of politics must be activated when the cold one is not enough, and as David McNally pointed out, they are still used in the Global South. While McNally focuses mainly on contemporary Sub-Saharan novels, he glances over the most effective present day example of this weaponizing: Sendero Luminoso’s use of the image of the pishtaco, a monster who would kill the children to rob them of their body fat so it could sell it in the market. Sendero was able to racialize the pishtaco as a white colonizer, and sow even more distrust of the Amerindians towards the white NGO workers. It was a key part of their Peruvian-flavoured Marxist story-telling.

At its best, Marxism with Gothic flavor appeals to the subconscious, making us feel the injustice, teaching us a primal instinct of repulsion to capitalism. It makes us gaze at the Monsters of the Market and understand that Capital lies behind them. Since his early correspondence with Ruge, Marx noted that he needed to “awaken the world from the dream of itself”. Marx’s Gothic imagery in Capital and the Eighteenth Brumaire was a way of telling the story of capitalism, and the conflict between bourgeoisie and proletariat, in a way that spoke to us directly, and mobilized us. The description of Capital as a vampire remains as memorable as ever.

Walter Benjamin took this much further.10 He wrote mainly in the interwar period- a time when psychoanalysis was a buzzword, and Lukacs had only recently published History and Class Consciousness in an attempt to link the subjective to the objective. It was also a time when the fascist monster was growing. Benjamin stressed the importance of imagery and revelation in bridging the gap between individuals and the collective understanding of capital. He brought insights from psychoanalysis into Marxism, and sought to break the hold of religion by means of what he called profane illumination– by intoxicating us with imagery to reach a revelation which inspires us. Heavily influenced by his Judaism, Benjamin sought out the historical memory for inspiration. By glancing at the Angelus Novus we understand that we must fight for the victims of Capital, to deliver a justice dedicated to their memory. In today’s world, we have no lack of sites to illuminate us: the lynching memorials; Standing Rock; the mass graves of the Paris communards or those of the Spanish Civil War; the river Rosa Luxemburg was thrown into; The Palace of La Moneda in Chile where Allende was murdered; the streets of the Soweto and Tlatelolco massacres; and of course the horrors of Auschwitz. The memory of the dispossessed stretches across time and space, waiting for justice.

III

Thomas Paine was not just trying to describe the kings as monsters, from which nothing could be expected except “miseries and crimes”.11 Paine also wrote, and attempted to put into practice, a political program for a better world. The formation of a mythology for the proletariat has been an integral part of the success of movements across the world. As Paine and Marx understood, gothicness is just the beginning. It gives us a way to tell a story which unveils the malice of our enemies, but we still require a positive force, a force of collectivity and millennialism to bring us together. Even the most mild form of leftist “othering”, the narrative of the 1%, presupposes the idea of a 99% that shares interests, and brings people together through their common dispossession.

Finding gaps in which Marxist ideology can be inserted has been one of the central research programs of Western Marxism. In essence, it articulates the Marxist view of the links between base and superstructure in a way that activates feelings, and the irrationality of being willing to suffer and die for a political program. The defeat of revolution in Western Europe came about from the strength of bourgeois ideology. It was able to perpetuate its hegemony. When the time came, there were not enough people willing to break their chains simultaneously. Many have written on this problem: Gramsci, Althusser and the Frankfurt School to name a few. After the Second World War, the golden age of capitalism provided a decent living for the working class in the centers of capitalism. Cultural critique or critiques of alienation were not enough to break the hold of the capitalist cultural hegemony. It could serve to identify weak points in societal cohesion, but it was never enough to inspire and guide a revolution. The Frankfurt School is an example of how critical theory can be divorced from practice when it is not grounded in class struggle.

Liberation theology provides a counterpoint of what is possible when class struggle advances ideology even within a reactionary institution like the Catholic Church. Taking inspiration from the Bible, religious figures reinterpreted passages that warned about the idolatry of money. Priests articulated how capitalism does not match the underlying values of society, and so were able to speak in the language of the people without abandoning their faith. Liberation theology set alight the underlying tensions present in many countries, and was particularly effective in mobilizing people in Nicaragua, El Salvador and Brazil. It was only defeated by an unholy combination of the Vatican and US imperialism, and has been replaced by religious faiths with a counter-revolutionary ethos.

Today, pessimism is warranted. To the historical defeat in the centers of Capitalism, we must add the collapse of the Eastern Bloc as well as the century of Latin American tragedies, where only Venezuela and Cuba barely hang on. Under a deluge of ideology the masses have abandoned liberatory faiths and embraced anti-communist worldviews. Socialism in our lifetime appears impossible, and the totems of revolution we hold dear have changed. This generation no longer venerates Che the way previous generations did. Che was not just a martyr who gave up a comfortable life for the cause— he was also someone who won. In this time of darkness, the voluntarism of a Che Guevara, who not only demanded, but exemplified a new type of person, a person who could challenge the US empire with dozens of “Vietnams”, fades away.

For a short while some heroic victories happened: US imperialism was forced to retreat from Southeast Asia and Nicaragua by guerillas. But this did not last. Today we look to more tragic figures like Rosa Luxemburg, and celebrate her supposed penchant for the spontaneity of the masses. We wait for the unplanned revolution, forgetting that Rosa was a tireless party organizer. A symptom indicating that we do not know where to begin. Somehow mass demonstrations against Trump and other right-wing populists are supposed to lead to a revolution, even when their politics are at best confused and the protestors hardly united by a material base. Those who praise spontaneity forget that groundwork has to be patiently lain, and even the most simple strike action requires tight organization. It is a wild dream to think that a social media hashtag will lead to the toppling of extremely resilient structures.

IV

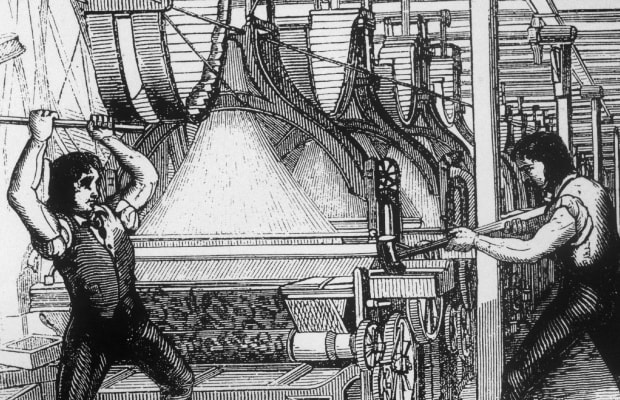

Culture changes rapidly. As E.P. Thompson relates in his Making of the English Working Class, the pre-revolutionary wave of the late 1700s took root mainly through two mechanisms: the establishment of the Correspondence Societies and the Dissenting churches. Unlike the French one, the second English revolution never took place as it faced a stronger ruling class. This ruling class acted to break these societies, and the story of the late 1790s culminates in the Despard execution of 1803. During the early 1800s, a counter-revolutionary culture war was also taking place. A new faith of poor and rich alike was disseminated, while serving the cultural hegemony of the ruling classes: Wesleyan Methodism. Encouraged and financed by the upper classes, it was a denomination that emphasized social order. This picture resembles the birth, growth and defeat of Liberation Theology in Latin America. The streets and mountains where Catholic priests would lay their lives are today full of the churches which have propelled extremist politicians to power in Colombia and Brazil.

But English history offers us hope. The counter-revolution did not last forever, it was only a temporary sleep. The misery which caused movements to arise remained. After the cultural counter-revolutionary offensive wore off, Methodist churches provided an individual locus for community outside the official sanctioned channels. This was not the high Anglican church but a rough community center. Methodism would breed Luddites and Painites within its ranks. It became a path through which other rebels would rise up the ranks and use their organizing skills and access to the community to launch new counter-hegemonic offences. Some Methodist preachers became preachers of class consciousness, and explained how the values laid out by the church were opposite to those of Capital. They became involved first in the Luddite movement, and later in the growing Trade Union movement, over which they came into conflict with the church hierarchy. Chartists and Trade Unionists alike benefited from the organizer school that was the Methodist Church.12

Providing places where the dispossessed can come together and find their commonality is of utmost importance to the present socialist movement. Working-class ideology must be produced and reproduced. The German and Austrian Social Democratic parties of the late 1800s and early 1900s understood this, and built schools, sports clubs and all sorts of facilities in proletarian neighborhoods, which laid down the foundations for their success. While we might stare at the proliferation of churches in the American continent, and see them as a lost cause, the material roots that gave origin to liberation theology and many other working-class movements like the Poor People’s Campaign of Martin Luther King Jr. are still there, and will not disappear anytime soon. These communities will surely undergo re-radicalization.

V

Shamans and totems provide an initial bridge to radicalizing people, because they break their social conditioning. But in the long run we cannot rely on the shamans because, even if they recognize that their power comes from us, we are tempted into the lie that without them we are nothing, and this gives them undue control over the movement. In fact, the opposite is true. They are nothing without us. Socialism is about collectivity, much more a religion than a magic. Magic is always a private thing, while religion relies on collective experience.

Today it is hard to ignore that religious feelings abound in the community that follows the terrestrial shamans. Bernie Sanders’ supporters do not care if the man is flawed, or if the odds are stacked against him. What matters is the process that brings them together towards political power. Their recipe is insufficient: the community needs to learn that their power lies not in their vote, but in their ability to stop the economy if they wish. By bringing people together in the same spaces, they are laying down the seeds for something bigger. The dispossessed need to realize that they already are bigger than the shaman who leads them. Shamanic movements suffer from the domination of a person. We can relate to this person, but he or she can have too much control over the movement and in crucial moments can initiate its downfall. Sendero Luminoso disintegrated after Abimael Guzman went from the invincible Inca Sun to a man behind bars. It was not their terrible treatment of other leftists within their territory, but the shattering of the shaman that ended them. We should ensure that a movement does not base itself on a leader but produces organic leadership. Otherwise tragedy awaits: Chavismo could survive Chavez because he actively trusted and followed the masses. Lula’s Sebastianism required the masses to follow instead of lead, which left the Brazilian Left disoriented and defeated, a situation that worsened after the personalist “Lula livre” demand was won.

The odds facing Lenin, Mao, Castro and Ho Chi Minh were never good. And the odds facing us today might be even worse. But by looking at history we can learn how they were able to unify, motivate and mobilize the people behind their program with grand narratives. These narratives are mixed and intertwined with religion, even if they are subconsciously secular versions of the prevailing faith. Demonstrating how the values of people do not correspond to the social system is a great weapon in the hands of organizers. Like Paulo Freire and Amilcar Cabral recognized, rearticulating and recreating our own culture is inherently revolutionary. The bridge to turn religions of the dispossessed into socialist movements is very buildable. In the West, Bloch understood this the best. In Latin America, Mariategui’s theorization surely had an influence on both liberation theology and Sendero Luminoso.

The history of revolution is plagued by millennialism. From those who died in the German Peasant War demanding omnia sunt communia during the Reformation, to the North Koreans inspired to fight against unthinkable odds by Juche, a thinly-concealed revolutionary Cheondoism13, religion serves as an inspiration. Any serious revolutionary should explore his local culture, and weaponize cultural cues to show the dispossessed how to stand together, and make us aware that we’re all in the same fight. Of course, not all cultures and icons are built the same: for example, American nationalism is hardly redeemable, tied as it is to white supremacy. But most icons are mixed, with Chavez’s reclamation of Bolivar as a positive example. Whatever the case, inspiration is needed to break social conditioning, reinstall a collective ethic, and defeat the exterminists.

This comes through understanding that the revolutionary fights for a terrestrial paradise, and makes the highest of wagers to do so. In today’s world, where religion remains the last relief of the masses, utopia and brotherhood blend in as a starting point. Religion has two sociological functions: integrating communities, and resisting change. The latter can be a double-edged sword, serving both a counter-revolutionary purpose and a revolutionary one, when people feel their entire livelihoods are being swept from underneath them. It is not strange to see that many revolutionary movements against accumulation by dispossession end up triggering religious feelings. There are many examples, from the earliest records of the new faiths sweeping Europe during the Reformation in the German Peasant War, to 17th century England, to more current examples across the world. It is hardly surprising that the hardest enemies of late-stage capitalism are indigenous people fighting for their lives. The rallying cry during the Standing Rock protests was to “kill the black snake”, the pipeline threatening water. The cosmovision in which water is life proved itself revolutionary when faced with settler-colonialism. It was armed to face the monsters of the market, and able to unify the dispossessed. We would be fools to ignore it.

- Peter Frase. Four futures: Life after Capitalism

- Jason Moore. Capitalism in the Web of Life.

- Ulrich Brand, Markus Wissen. The Limits to Capitalist Nature: Theorizing and Overcoming the Imperial Mode of Living.

- See Aaron Bastani, “Fully Automated Luxury Communism: A manifesto” for a clear exposition of this position.

- A longer discussion can be found in John Smith’s “Imperialism in the Twenty-First Century: Globalization, Super-exploitation and Capitalism’s final crisis”

- Wainright and Mann, Climate Leviathan: A political theory of our planetary future

- See the story of Zombies in https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/10/how-america-erased-the-tragic-history-of-the-zombie/412264/

- A full story of this is provided by David McNally’s Monsters of the Market

- Thomas Paine, Rights of Man

- Walter Benjamin’s use and understanding of the Gothic is best described in Margaret Cohen’s Profane Illumination.

- Thomas Paine, An Essay for the Use of New Republicans in Their Opposition to Monarchy

- Nigel Scotland, “Methodism and the English labor movement, 1800-1906”

- Cheondoism is an indigenous religion of Korea, which mixes shamanism with Confucianism. While Juche was not articulated until 1955, the “self-sufficiency” aspect was present since the early Korean fighters. The relation between Juche and Cheondoism is described in Roland Boer’s Red Theology.