Ian Szabo writes on the history of the African Blood Brotherhood as part of a broader tradition of black liberation that merged with International Communism after the Bolshevik Revolution.

From 1928 to 1934 the slogan “Self-determination for the Black Belt” became the core of the Communist Party of the United States’ (CPUSA) approach to Black Liberation. A common understanding among the non-Stalinist left of this strategy is that it was cooked up by Stalin in the late 1920s in order to purchase a positive image for his bureaucratization of the Communist International (Comintern) as he ascended to power.1 Because of this narrative, among many others, we are left in the communist movement with a false dichotomy between national liberation and social revolution, despite the reality that self-determination has always been a necessary part of the revolutionary transformation of society. Surrendering it to Stalinism betrays a fundamental basis of revolutionary Marxism rightly referenced by Lenin: “[to] not be a secretary of a tred-union but a people’s tribune who can respond to each and every manifestation of abuse of power and oppression[.]”2

Nothing exposes this false dichotomy between socialism and self-determination better than the history of black struggle and its relation to the US Communist movement. To fully grasp this history we must look at how black radicals developed a tradition of struggle on their own and merged it with the practice of international communism in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution. This requires looking at the history of the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB), the first Black Communist organization, as well as its founder Cyril Briggs.

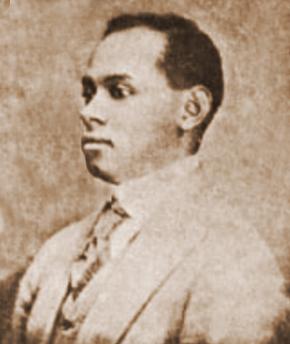

Briggs hailed from the Caribbean island of Nevis where he had refused to abandon his heritage as a black man and integrate into society with his lighter-skinned complexion.3 Alongside many other native West Indians of the period, he immigrated to the United States, eventually Harlem, in 1905. Due to a stutter that prevented him from being able to speak fluidly with others, Briggs chose to focus on writing rather than organizing, becoming an intellectual and writing for the Amsterdam News in 1912. The particular event that sparked his transformation into a Marxist was in the period just before the October Revolution in 1917; Briggs was faced with the ugly reality that Woodrow Wilson’s call for all nations to have the right to self-determination was bankrupt, revealed by the execution of 13 black mutineer soldiers in Houston, Texas.4 Although the unveiling of Wilson’s Fourteen Points later on would cause Briggs to waver, his primary political orientation would be towards the Socialist Party; and despite the SP’s tendency towards a class-first politics that failed to fully comprehend the oppression of African Americans, Briggs would put forward the argument that for black people, “no race would be more greatly benefited by the triumph of Labor”.5

Briggs’ disillusionment with liberal insincerity and movement towards socialist politics was accompanied by the development of what would become known as the Black Belt Thesis. During his last months at the Amsterdam News Briggs would write an essay entitled: “Security of Life’ for Poles and Serbs- Why Not for Colored Americans”, where he put forward the idea of a “colored autonomous state” somewhere in the upper northwest or far west. He chose these regions because he believed they had not been as settled as most regions in North America. Although there are differences in terms of the region this model aimed to use, this shows that the idea of an autonomous African American nation within the American continent was not simply a project cooked up by Stalin in the late 1920s. Rather than a foreign product, the Black Belt began as an attempt by an African American socialist searching to synthesize the aspirations of the African liberation struggle from which he came with the politics of revolutionary Marxism.

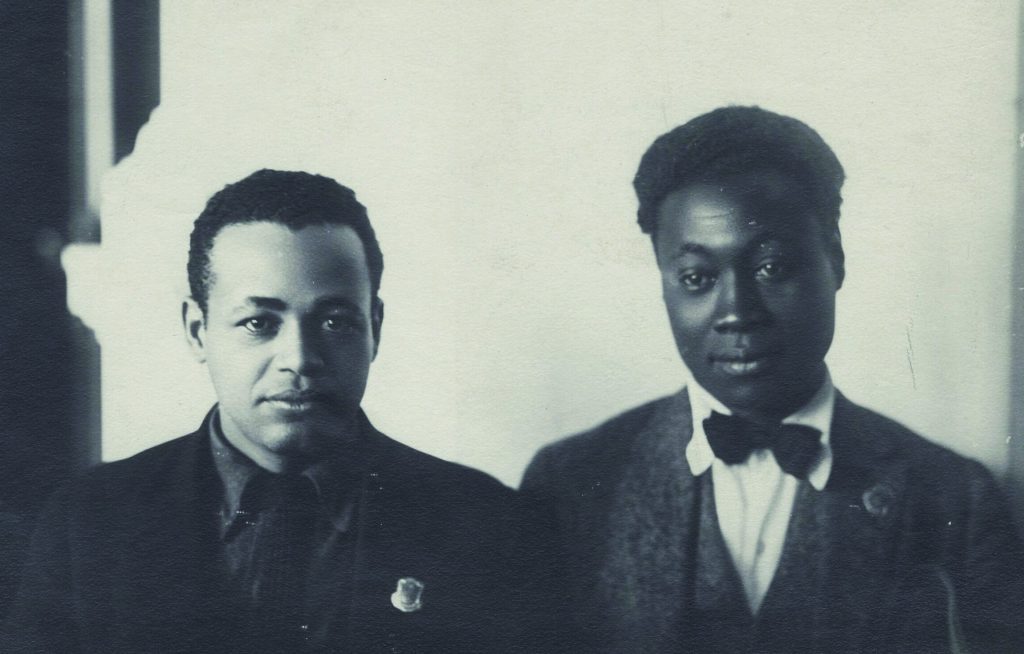

Eventually, socialist politics and opposition to WW1 would put Briggs in conflict with editors of the Amsterdam News. At the same time Briggs was forging friendships with the likes of Otto Huiswood, Grace Campbell, Richard B. Moore, W.A. Domingo, Hubert Harrison, Claude Mckay, and other radicals in Harlem. It was from this milieu that the journal Crusader was born. The period following the October Revolution in the United States saw a great deal of confidence and energy in the American left, signified in part by the Crusader and the ABB. This energy combined the turmoil that broke out after WW1 with the re-alignment of the global socialist movement and the birth of the Comintern. Briggs would be the intellectual powerhouse of the Crusader, continuing his arguments for the benefits of uniting with the workers’ struggle, while also theoretically uniting the African diaspora’s desires for self-determination with the Comintern’s goal of a Socialist Co-operative Commonwealth.6 For Briggs, Black liberation did not necessarily require a communist vision, but it was the preferable grounds or stepping stone by which to achieve it. In order to understand why Briggs believed that the communist vision of national liberation was superior to Marcus Garvey and the UNIA, we have to take a look at the radical transformations that had occurred in the Comintern.

It cannot be understated how profoundly the formation of Third International widened the international character of the historical socialist movement, to which Briggs was responding. As Donald Parkinson has pointed out, “the Third International was an improvement of the Second. Marxists moved towards a truly internationalist universalism which saw the entire world as having agency in the revolutionary process and struggled politically against internal European chauvinism.”7 Taking direction from Nikolai Bukharin’s remarks on the subject, the resolutions put forward in the fourth congress of the Comintern cemented the point that the global communist movement had everything to gain through an alliance with oppressed people seeking national self-determination in the colonized world, as the task of the “[Comintern] on the national and colonial question must be based primarily on bringing together the proletariat and working classes of all nations and countries for the common revolutionary struggle.”8 This allowed Briggs and those around him to find a place they felt they did not have in the old socialist parties connected to the Second International, while also pulling them away from reactionary forms of nationalism that failed to properly deal with the nature of imperialism and colonialism.

At the same time that the Comintern was making strides towards a more forward-thinking international, Marcus Garvey was revealing his political commitments to reject socialism and even anti-racism. Already before the founding of the Crusader, W.A. Domingo had been fired from Garvey’s newspaper, Negro World, for espousing socialist politics. He would later become a collaborator with Briggs and co-found the Liberator with fellow ABB member, Richard B. Moore.9 According to Briggs in the foundational documents of the ABB, Garvey’s form of capitalist separatism would necessarily lead to the downfall of any attempt to gain self-determination, as inevitable capitalist crisis would wreck such attempts and sap morale from the liberation movement.10 A decade later, Briggs would more brutally relitigate this issue, pointing out that the Garvey movement failed to combat racism by ceding the American continent to white people, resulting in at least tacit collaboration with the Ku Klux Klan.11 In these criticisms, Briggs remained consistent with his argument that although socialism is not necessary for black for liberation, a socialist commonwealth on an international scale nevertheless provided the best chance for that task.

Although Theodore Draper characterized the ABB as being a typical iteration of the propagandist organizations of early century Harlem, it was equally familiar to the history of intellectualism in the worker’s movement, from Marx’s own Communist League to the circles the Bolsheviks emerged from.12 Of course, like any political organization it also had a program which formulated its basis on four points: “(1) the economic structure of the Struggle (not wholly economic, but nearly so); (2) that it is essential to know from whom our oppression comes… and to make common cause with all forces and movements working against our enemies; (3) that it is not necessary for Negroes to be able to endorse the program of these other movements before they can make common cause with them against the common enemy; (4) that the important thing about Soviet Russia… is… the outstanding fact that [it] is opposing the imperialist robbers who have partitioned our motherland and subjugated our kindred, and… [it] is feared by those imperialist nations.”13 The 1921 program fully articulated the class-based form of Black liberation Briggs sought to convey, utilizing the anti-imperialist commitments of the Comintern to build a bridge with the Bolshevik Party in Russia.

To fully grasp the historical importance of the ABB we must look not only to Briggs but to the entire membership. Drawn into the orbit of the ABB through her activism with the Committee on Urban Conditions among Negroes in Harlem, Grace Campbell was a social worker, court attendant, and prison officer convinced by the ABB’s call for socialism, black liberation, and decolonization.14 Alongside Hermina Dumont, Campbell was further radicalized by the international character of the communist movement. However, despite her involvement, the ABB was unfortunately an organization dominated by men, and so Campbell was relegated to secretarial tasks despite being on the “Supreme Council” of the ABB.15 Campbell dealt with the male chauvinism of the ABB through her involvement behind the scenes, as she held Supreme Council meetings and distributed the Crusader from her home.

According to McDuffie, Grace Campbell took the role of a mother figure for the ABB and much of the early communist left in Harlem. Not only a hub for the movement itself, Campbell’s home was open to anyone in need of food and shelter. It is true that this was a deeply gendered role to be given and taken up by Campbell, but the flipside of this is that it was also a source of power for a woman in the ABB able to “consciously construct and strategically perform this matronly persona to exert influence with women and to challenge the sexist agendas of black male leaders and to exercise influence in male-dominated political spaces”.16 Although much of this essay deals with the political orientation of the ABB, what is present in its history, as in most early socialist history, is a profoundly male-dominated dynamic which may be highly capable of dealing with the questions of decolonization and imperialism but fails to factor in, let alone fully integrate, the struggle of women workers.

A number of Grace Campbell’s comrades in her time as a socialist organizer would join her in Briggs’ ABB, but few would grow as close to Briggs himself as Richard B. Moore. A fellow radical from the Caribbean that found himself in Harlem, Moore came into Briggs’ orbit through his journalistic work and eventual founding of the Emancipator alongside W.A. Domingo.17 One point made by Moore himself about the ABB is worth keeping in mind: that although most of the history of the organization generally paints it as either a response to Marcus Garvey’s UNIA or a recruitment operation for the communist movement, this ignores the actual dynamics that produced the ABB. The reality is much more complicated, as many of the figures that made up the ABB had worked together prior to the organization’s formal founding. This means that the ABB was not necessarily a response to another organization but something which emerged from the intellectual and practical work black socialists had been committed to for years beforehand. Although many of these members certainly saw an ally in Leninism and the Comintern, their project had already developed its own political lines which the communist movement spoke to.

The campaign against Garveyism is a particular subject in which one can clearly see what Moore was getting at when he made this claim, as he did not fall in line with it. The aforementioned campaign was certainly in the right with regards to principled communist politics, but Moore refused to take part, preferring not to “[join] with the oppressors of your own people” and “betrayal of the right to speech.”18 As these debates were in the pre-Stalinized communist movement, the assumption that there needed to be a principled black united front with a right to criticism and free speech was prefigured within the movement and Moore’s conception of black socialist politics. If the ABB were simply made to respond to the UNIA or recruit black people to the communist movement, Moore would not have had any incentive to refuse to engage in this campaign, as it would have been perfectly consistent with the raison d’être of the organization. Instead, Moore’s response at the time was perfectly consistent with an organization that had always had its own agenda and vision of liberation.

In 1919-20, the ABB’s vision of liberation was encapsulated by a moment in Bogalusa, Louisiana, discussed by Moore in an article named after the city. The United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners (UBCJ), International Union of Timber Workers (IUTW), and American Federation of Labor (AFL) had been organizing across racial lines in the city but were eventually attacked by an organization that synthesized both the redemption narrative and ethos of the Ku Klux Klan and the nationalism of the first red scare: the Self-Preservation and Loyalty League.19 Their target was the head of the union of African American sawmill workers and loggers, Sol Dacus, who would be saved by his shotgun-carrying white comrades, Stanley O’Rourke and J.P. Bouchillon. Gunfights broke out because of this, resulting in the deaths of O’Rourke and Bouchillon, alongside the president of the Central Trades and Labor Council Lem Williams and carpenter Thomas Gaines. Moore’s and Brigg’s own articles would have been known to the multi-racial workers of Bogalusa too, as they were avid readers of the Messenger and Crusader. After the killings, Moore’s article in the Messenger praised these men for having put lives on the line for their fellow black workers in his article “Bogalusa”:

Williams, Gaines, and Bouchillon have given their lives. O’Rourke imperilled his life, in the cause of true freedom. Not for white labor, not for black labor (though they died defending a [black worker]), nor yet for any race or nation, did they make the supreme sacrifice, but for Labor, that great university of fraternity of striving, suffering human-kind which though despoiled, despised, and rejected, alone holds promise for the emancipation of the race.20

This further demonstrates Moore’s argument that the ABB was a novel organization that neither responded to nor was subservient to another organization. Just as the theory of an autonomous African American nation was not cooked up by Stalin but a theory developed by Briggs, so too was the program of the ABB an expression of totally independent thinking of its members.

To further develop a rich image of the ABB we must look not only to understand its political dimensions, but also its cultural contributions. To do so we must look at another one of its members, the great poet Claude McKay. In the pages of the Liberator, Max Eastman’s newspaper, McKay would publish his seminal poem “If We Must Die” only two months after the founding of the African Blood Brotherhood, a poem which presented an explicitly revolutionary perspective which contained “no impotent whining… no prayers to the white man’s god, no mournful Jeremiad.”21

Shortly after its program was fleshed out and articulated, the ABB was integrated into the Communist Party. Earlier in May 1920, a convention was called among the various emergent communist parties that had not yet merged, the United Communist Party (UCP), Communist Party of America (CPA), and Communist Labor Party (CLP). The UCP had displayed a particular sensitivity to the question of Black liberation but the ABB remained officially distant due to the other parties’ lack of similar commitments. However, by 1921, Briggs would appear as a delegate for the ABB at the founding conference for the Workers Party of America (WPA) in 1921, later to become the Communist Party of the United States of America.25 Otto Huiswood became the head of the WPA’s “Negro Commission”, which was a good start for dealing with racial antagonism in the emerging party despite the persistent presence of neglect, and patronizing attitudes towards black members of the party.26

During this same period, the ABB experienced a bump in membership that forced it to choose between languishing in sectarian obscurity or fully integrating into the CP. A number of the leaders from Marcus Garvey’s UNIA had come on side to the ABB due to the former organization’s sketchy business practices, but these members were not particularly enthused with the idea of affiliating to the emerging Third International.27 To make things more difficult, the result of this growth convinced the ABB leadership to attempt a fundraiser for the creation of a new newspaper to named the Liberator, which not only failed to emerge but exhausted the continuation of the Crusader. With Briggs’ journal out of commission, he began working at the national office of the Friends of Soviet Russia in 1922, becoming an organizer at the Yorkville branch of the WPA, and managing to reclaim the name of his former journal in the form of the twice weekly Crusader News Service with the assistance of Grace Campbell.28 Although the UNIA continued to hemorrhage membership due to nonsense like bartering with the KKK, Briggs found himself unable to convince its membership to join the struggle for communism, and the ABB began to decline despite attempts to keep it afloat through sponsoring cooperative stores. By 1924, the ABB would become fully integrated within the WPA.

Ultimately, the ABB itself only existed for a short five years, but it left a huge impression on the American communist movement and its core membership would re-emerge in the nascent communist movement as the American Negro Labor Congress. Those who had built the ABB went on to become active organizers long after its demise, empowering African American workers throughout the southern United States. Their legacy is the idea that communism was, and still is, a vehicle towards self-determination and emancipation of all of the world’s oppressed. Solidarity of the entire international working class was at the core of their day to day political organizing, knowing that they could never be free so long as workers elsewhere were not.

- Lee Sustar writing for the Socialist Worker provides a perfect example of this despite the articles’ otherwise strong merits, and although this author counts themselves as a Leninist opposed to Stalinism, we must deal with the realities of the history we inherit rather than write off the mistakes. Sustar, Lee. Self Determination and the “Black Belt.” Socialistworker.org. https://socialistworker.org/2012/06/15/self-determination-and-the-black-belt (accessed 12/11/19)

- Lenin, Vladimir. Lih, Lars T., and Lenin, Vladimir Ilʹich. Lenin Rediscovered : What Is to Be Done? In Context. Page 746. Historical Materialism Book Series. Chicago, Ill. : [Minneapolis, Minn.]: Haymarket Books ; Distributed by Consortium Book Sales, 2008.

- Solomon, Mark I. The Cry Was Unity: Communists and African Americans, 1917-36. Page 5. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998.

- Ibid.

- Briggs, Cyrill. “Make their Cause Your Own”. The Crusader, 1919. Heideman, Paul M. Class Struggle and the Color Line : American Socialism and the Race Question 1900-1930. Page 240. Chicago: Haymarket Books. 2018.

- Briggs, Cyrill. “The Salvation of the Negro”. The Crusader, April 1921. Heideman, Paul M. Class Struggle and the Color Line : American Socialism and the Race Question 1900-1930. Page 258. Chicago: Haymarket Books. 2018.

- Briggs, Cyrill. “The Salvation of the Negro”. The Crusader, April 1921. Heideman, Paul M. Class Struggle and the Color Line : American Socialism and the Race Question 1900-1930. Page 258. Chicago: Haymarket Books. 2018.

- Degras, Jane Tabrisky, and Royal Institute of International Affairs. The Communist International, 1919-1943; Documents. Page 141. London: F. Cass, 1971. Print.

- Briggs, Cyril. Heideman, Paul M. Class Struggle and the Color Line : American Socialism and the Race Question 1900-1930. Pages 199-200. Chicago: Haymarket Books. 2018.

- Foner, Philip Sheldon, and Allen, James S. American Communism and Black Americans : A Documentary History, 1919-1929. Page 22. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1987.

- Briggs, Cyril. Foner, Philip Sheldon, and Shapiro, Herbert. American Communism and Black Americans : A Documentary History, 1930-1934. Pages 78-81. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991

- Draper, Theodore. American Communism and Soviet Russia, the Formative Period. Page 325. New York: Viking, 1960. Print. Communism in American Life.

- Briggs, Cyril. “Program of the A.B.B.- Offered for the Guidance of the Negro Race in the Great Liberation Struggle.” The Crusader. Heideman, Paul M. Class Struggle and the Color Line : American Socialism and the Race Question 1900-1930. Pages 265-266. Chicago: Haymarket Books. 2018.

- McDuffie, Erik S. Sojourning for Freedom : Black Women, American Communism, and the Making of Black Left Feminism. Pages 32-34. Durham [NC]: Duke University Press, 2011.

- Ibid. Page 37

- Ibid. Page 38

- Moore, Richard B., Turner, W. Burghardt, and Turner, Joyce Moore. Richard B. Moore, Caribbean Militant in Harlem : Collected Writings, 1920-1972. Blacks in the Diaspora. Pages 32-39. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988.

- Ibid. Page 39.

- Norwood, Stephen H. “Bogalusa Burning: The War Against Biracial Unionism in the Deep South, 1919.” The Journal of Southern History 63, no. 3 (1997): 591-628.

- Moore, Richard B., Turner, W. Burghardt, and Turner, Joyce Moore. Richard B. Moore, Caribbean Militant in Harlem : Collected Writings, 1920-1972. Blacks in the Diaspora. Page 141. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988.

- Wallace, Thurman. “NEGRO POETS AND THEIR POETRY.” The Bookman; a Review of Books and Life (1895-1933), 07, 1928, 555

- McKay, Claude. The Liberator. Page 21. July 1919 https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1919/07/v2n07-w17-jul-1919-liberator.pdf

- Solomon, Mark I. The Cry Was Unity: Communists and African Americans, 1917-36. Page 8. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998.

- Robinson, Cedric J. Black Marxism : The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Page 220. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

- Solomon, Mark I. The Cry Was Unity: Communists and African Americans, 1917-36. Pages 17-21. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. Pages 26-27

- Ibid. Page 28