Hank Kennedy presents and assesses the many reactions to comic books by different strata of the socialist Left during the Comic Book Scare of the 1950s.

Introduction

In a pair of articles I’ve written, one about the anti-comic book movement of the 1950s and another about the life of comics publisher Lev Gleason, the issue of socialist reactions to the Comic Book Scare has come up. The purpose of this article is to look at what different left-wing tendencies were saying about comics in the period between 1948, the year of the first comic book burning in Spencer, West Virginia, and 1961, the year the Marvel Universe was born with the first issue of the Fantastic Four, assessing both what they got right and (mostly) wrong about the comic book art form.

The Trotskyists

U.S. Trotskyist writings on comic books generally appeared in the Militant, the newspaper of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and “orthodox” Trotskyism. The first discussion of comic books occured in the January 21, 1952 issue in an article entitled “Comic Strip Culture.” This piece addressed the use of American comic book propaganda in Ceylon. The writer of the article took issue with both the content of the comics, which appeared to be crude political propaganda, but also with the comics form itself. The anonymous author stated that comics are a “narcotic to which underdeveloped and adolescent minds are very much addicted.” They continued, stating that comics would result in a loss of attention span and literacy, and “will result in a state of chronic imbecility.” For the author of the article, it was the combination of words and pictures that was dangerous, along with the content of those words and pictures. The irony of the Militant itself containing political cartoons that combine words and pictures goes unremarked upon. There was one critical letter responding to this article in the March 3, 1952 issue by D.B., who explained that comics in themselves were not bad and that they could be used to spread socialist messages.

In the September 15, 1952 edition of the Militant Jack Bustelo wrote an article “For the Good of Our Minds,” which dealt with the effects of media violence on developing children. The last part of the article addressed a case of comic book censorship when the Pentagon created a list of seven comics that were to be kept out of the hands of Navy sailors because they could be deleterious to morale. No titles were provided, but an example of one grim war comic was cited in which a soldier complains “All I’ve done since I’m out here in Korea is burying my buddies.” The author dryly noted the hypocrisy of the government allowing children to view violent content freely while adults are kept from reading the same thing.

1954 was the key year for the anti-comics movement and this was reflected in the pages of the Militant. In the May 10, 1954 issue, Evelyn Reed wrote a highly favorable review of Psychiatrist Frederic Wertham’s anti-comic treatise, Seduction of the Innocent, under the title “Comic Books-McCarthyism For the Children.” Wertham’s assertions were regurgitated almost verbatim by Reed in the review. These include; that crime and horror comics are read primarily by children, that most comics are crime comics (Wertham defined any comic book in which illegal activity is depicted as a “crime comic”), and that children are directly influenced to commit crimes based on what they read in comic books. Crime Does Not Pay, which was published by one-time Communist Party member Lev Gleason, was brought up, although not by name, as a comic with “six million readers.” One of the largest errors in Reed’s review is the example of Superman. Reed, again basically repeating Wertham, cited Superman as a character of Nazi propaganda despite him having been created by two Jewish men, Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster. Reed even stated that Superman is a “big, blonde, muscular Nordic hero,” something even a layman would know is incorrect since Superman had and had always been represented with black hair, not blonde. More inexcusable than the treatment of Superman was the treatment of homosexuality, under the heading “Glorify Degeneracy,” which itself reads like antigay propaganda straight out of the Third Reich. Essentially, Batman, Robin, and Wonder Woman are accused of grooming children to be gays and lesbians, and homosexuality is presented as a degenerate act. The review concludes by stating that comics are raising a generation of juvenile delinquents who will soon become Nazis.

In the August 2, 1954 issue of the Militant, the paper ran two small articles under “Notes from the News” that dealt with attempts to ban comics. One covered an attempt to ban comics in California and the other repeated the paper’s earlier support for Frederich Wertham. In the September 20, 1954 issue, the Militant ran another “Notes from the News” in which they reported that William Gaines, publisher of EC Comics, had decided to shut down his line of horror and crime comics. EC Comics, probably the most progressive of all the major publishers, was on its way out of business. A year later, the Fall 1955 issue of the Fourth International featured an article by Joyce Cowley entitled “Youth in A Delinquent Society: What Should Be Done?” Cowley basically repeated an article she wrote for the Militant around two years prior. Although she also did not think highly of comics, she also faulted Frederic Wertham for pushing crime comics as a cause of juvenile delinquency. Instead, she argued “to condemn them as the cause of juvenile crime is like saying – as some people do – that the increased use of narcotics is due to the fact that drugs are more readily available than they were 20 years ago.” So there was clearly a difference within the SWP as to whether comics caused harm or whether they were the result of greater societal forces. However, no regular writer was willing to make the case that comics were good in themselves and condemnations of comics continued; in the March 20, 1959 issue of the Militant, an anonymous author gleefully recounted the difficulties of the comics publishing industry caused by the efforts to ban comics, citing a corresponding increase in the reading of classic literature.

The other major American Trotskyist publication at this time was Labor Action which was published by the Independent Socialist League (ISL), formerly known as the Workers Party. The ISL had split from the SWP over differences as to whether the Soviet Union was a “deformed worker’s state,” worthy of defense by revolutionary socialists, or a “bureaucratic collectivist” one that deserved no such defense. The ISL may have differed with the SWP on the question of the class character of the Soviet Union, but they were in complete agreement on the question of comic books and this view appeared in their newspaper.

An article called “Let ‘Em Read Comics” appeared in Labor Action on July 31, 1950. The article has nothing to do with comics, other than to humorously offer the title as a solution to the problem of underfunded libraries in the United States. The idea of reading comics is contrasted unfavorably with that of reading library books. In the May 24, 1954 issue, Labor Action comics were mentioned in Victor Howard’s article “Myths About American Superiority: The Other Side of the Picture.” Howard considered the preponderance of comics sold in the United States a mark of American cultural inferiority when compared to the number of other books sold. Similar sentiments appeared in “The American Way of Life” from the January 2, 1956 issue when again, the number of comic books read is reported negatively. The unspoken assumptions at play are that comic books are for children or the underdeveloped.

Irving Howe, who was both one of the New York Intellectuals and a member of the ISL, as well as, at one point, the editor of Labor Action. Howe wrote the article “Notes On Mass Culture” for the magazine politics in the Spring, 1948 issue. politics was founded by Dwight McDonald, whose politics vacillated wildly from “orthodox” Trotskyism to the “heterodox” Trotskyism of the ISL, to anarchist pacifism and politics was a forum for different tendencies of the non-Stalinist left. The viewpoint of the New York Intellectuals was generally one of cultural pessimism, and they “associated mass culture with either the popular front (on the left) or conformist culture (on the right).” The prevalence of mass entertainment, from this perspective, was a political problem, or even a crisis, one which helped explain the existence of a ‘mass man’ vulnerable to “totalitarian propaganda and control.”1 Howe’s article fit comfortably into this pessimistic schemata. He viewed comics as being entirely intended for children and considered adults who read comics to be regressing towards childhood while “the numerous comics that are little more than schematized abstractions of violence and sadism quickly push children into premature adulthood.”

The UK Trotskyists were as anti-comics as their American counterparts. The “orthodox” Trotskyist publication the Socialist Outlook ran an article on July 25, 1952, titled “Ban This Deadly Muck!” by Nora Emmett. Emmett called for a ban on war comics that included racist and anti-Communist propaganda, citing the example of Battle Stories by Fawcett Publishing. While Emmett’s concern with the content of comics, rather than the form, is admirable, she fell into the trap of assuming that comics like these are things children must be protected from instead of a media that all ages could (and did) read. Less discerning was Cliff Slaughter in his December 1958 Labour Review article “Race Riots: the Socialist Answer.” Slaughter cited “horror comics” that are “directed especially towards young people” as an example of “a decaying capitalist society.” Unlike Emmett, Slaughter castigated an entire genre regardless of political content. Another article from this tendency dealing with comics was Peter Fryer’s “Freedom of the Individual” from the August-September, 1959 Labour Review. Fryer characterized comics, along with other elements of popular culture as something “imposed on ordinary people by big business.” He continued, stating that “the thriller and horror comic combine violence and pornography, ‘retool for illiteracy’ and prepare the reader’s mind for war.” At no point does Fryer consider that horror comics are something people might want to read or that writers and artists might exhibit any sort of craft in creating them. Instead, horror comics are spontaneously generated by big businesses as a form of brainwashing.

Further attacks were launched by the Socialist Review Group, a group of “heterodox” Trotskyists who held that the Soviet Union was “state capitalist.” In the September 1958 issue of their newspaper Young Socialist, writer John Phillips, in an article titled “A True Culture?”, cited “horror comics” as a method the ruling class was using to pacify “the industrial struggle” . He also negatively mentioned “Elvis the Pelvis and other gimmick-ridden crazes” as ruling class distractions from the threat of thermonuclear war. A later negative reference to comics appeared in the February 1959 issue of the Socialist Review in Graham Richard’s article “Man, Money, and Morals.” Richards stated that the process of the brutalization of mankind can “not only be seen in horror comics, horror films, horror bombs, the commercialization of culture but also…the scientific exploitation of the worker at the point of production.”Mentions of horror comics after 1954 are interesting because, at this point in comics history, American horror comics had virtually disappeared due to the stringent regulations of the Comics Code, which forbade zombies, vampires, ghouls, and other staples of the genre.

The Marxist-Leninists

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was one of the most anti-comics forces in the United Kingdom. The 1949 CPGB pamphlet Get Out called for the defense of British cultural heritage and “the protection of our children from the spread of these alien and disgusting attacks on their moral welfare.” The Party’s cultural pronouncements followed this highly nationalistic and chauvinistic line. E.P. Thompson, then a member of the Communist Party, gave a speech in April, 1951 that was reprinted in the CPGB’s Arena in which he charged that comics and other aspects of U.S. culture carried “a poison [that] can be found in every field of American life.” A 1951 June-July Arena article argued “comics portray fantasies of the future all fascist in character.”2 The CPGB thought opposition to American comic books was so important that their 1955 Campaign Platform called for “effective action to prevent the publication and sale of the American-type comics which have so shocked the public conscience.”

Peter Sedgwick was notably anti-comics while he was a CPGB member , before he went over to the Trotskyist Socialist Review Group due to the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Uprising in 1956. In 1954 he wrote in the article titled “America Over Britain” for Oxford Left, arguing that comics from America were “Dulles-jingo comics” (a reference to CIA head Allen Dulles and his brother, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles). He went even further in 1955, writing in the article “Psychopolitics” for the Clarion that “pre-conditions for psychological ill-health will be liquidated in a society without the possibility of profit-making in horror-comics, [and] brutal films.” Sedgwick argued that the horror genre will disappear under socialism along with homosexuality, which he characterized as another social ill.

One of the CPBG’s biggest salvos against comics occurred in the August 16, 1954 issue of the Daily Worker with the article “Still Cashing in On Muck.” The article attacks a specific comic story, “You, Murderer” from EC Comics’ Shock Suspenstories 14 (April, 1954). The Daily Worker presented a single panel out of context to make the case that the story was endorsing murderous violence against suspected Communists.3 In actuality, the plot of the story is that “you” are hypnotized by a man to kill his wife after being given the hypnotic suggestion that she is a Communist spy seeking to blow up the city with an atomic bomb. The story cleverly associates hypnotism with anti-Communist paranoia, as both cause normally moral people to do things that they consider to be immoral. However, the CPGB either misread or ignored this message that actually agreed with their stated politics.

Unlike the Trotskyists, the CPGB backed up their anti-comics position with action. The CPGB was the genesis behind the Comics Campaign Council, a broad organization dedicated to opposing “American-style” crime and horror comic books. At first, the CPGB stressed the anti-American nature of the campaign, since they viewed comics as perpetuating cultural imperialism against Britain. Later emphasis was shifted to the form of horror and crime comics themselves, regardless of their American nature. At the same time, the CPGB disappeared into the Comics Campaign Council, doing all campaigning as the mass organization rather than as Communists.4

The CPGB also used their influence in the National Union of Teachers to further the anti-comic book campaign. The union issued a statement calling on churches, publishers, newsagents, and others to “join forces to remove this corrupting influence from the bookstalls in the dingy back streets.” School headmaster George Pumphrey wrote the influential pamphlet “The Comics and Your Children” which offered a defense of British humor comics before turning towards condemnation of American-style comics “that wallow in crime, horror, violence and sex.”5 Pumphrey echoed the prevailing sentiment of the time; that comics are read mostly by children, that children will imitate the violence in comics, and praise for Fredric Wertham. The pamphlet even included the same panel the Daily Worker printed from “You, Murderer,” again taken completely out of context to make it seem like the comic was an anti-Communist attack.6 One legitimate political point was made when the author opposed the use of racial stereotyping present in an adventure comic, but this was buried under aesthetic concerns and misreading of the morals of different comics. The British campaign against comics was eventually successful with the passage of the Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act of 1955, which banned any comic books that portrayed “(a) the commission of crimes; or (b) acts of violence or cruelty; or (c) incidents of a repulsive or horrible nature.”

The Communist Party of Australia had a similar view of comics to the CPGB. In an August 1959 pamphlet, Education in Crisis Communist Party member and educator W.E. Gollan stated that comic books had a “demoralizing influence” on young people and that, furthermore, “debased comic books…stimulate anti-social eroticism and crime amongst children and youth”. In “The Present Problems of the Unions” Communist Party leader Lance Sharkey lists the “criminal efforts to pollute the minds of the people by means of the degraded mental fodder it purveys through the monopoly-controlled press, television and radio”. He includes gambling, westerns, horror films, “perverted music”, and horror comics as examples of this mental pollution.

Interestingly, the Communists in Australia actually began fulminating against comics earlier. In an issue of the Communist newspaper The Tribune the article “Tragic Comics” contended that comics were “doing their sinister worst to destroy our national character” and that they were “spreading their poisonous doctrines of brutality, sadism and supermen.”7 A later anti-comics article in that same publication by Rex Chiplin was titled “I Spent a Week In a Literary Sewer,” which combined attacks on the “pornography, sex, sadism, brutality and illiteracy” found in newsstand comics with a more political critique of the anti-Communist and racist war comics being sold.8 The Communists used their influence within the trade union movement to further their opposition to comic books. The Queensland Trades and Labor Council, a Communist stronghold, passed a resolution declaring “complete opposition to the corruption of Australian children’s and adolescent minds by mass distribution of murder, crime, horror and sex publications.”9 The Australian Journalists Association, a journalists’ trade union, released their own anti-comics pamphlet Sin in Syndication: A Cultural Crime Wave That Menaces Australia, which repeated the standard objections to comics violence, sadism, etc., but also included an economic argument that when comics were imported from America, employment of domestic writers and artists suffered.10 The Communist Party of Australia entered into an alliance with social conservatives, including Catholic Churches and Chambers of Commerce to fight off comics, but the result was not to make comics more politically progressive. Instead, the comic book reprinters established a code that virtually enshrined conservatism into the medium including a mandate that law enforcement would always be respected and that slang would be eschewed to avoid damaging young readers’ grammar.

The Communist Party of Canada supported comic book bans along with their Australian and British comrades. In the publication National Affairs, Annie S. Buller and Florence Theodore wrote in 1953 that the Labour-Progressive Party (the legal arm of the Canadian Communists at that point) would protect Canadians “from the pestilent crime comics and other harmful reading matter to be found on our newsstands today.” This in itself was an odd campaign plank given that Canada had already banned comics that depicted crimes in 1949.11 The lone Labour-Progressive MPP in Ontario, Joe Salsberg, gave a speech expressing his outrage at crime and horror comics in March 1952. Salsberg castigated the Attorney General for not doing enough to curb the spread of horror and crime comics and praised the work of Frederic Wertham. Oddly for a Communist, Salsberg also remarked that the Pope was in favor of his efforts to combat comics.12 The press of the party also attacked the comics in their publication the Canadian Tribune. Writer Margaret Reeves said that these comics were harmful to “the Canadian way of life.”13 In the same issue, the paper ran a survey of problems with comic books. The Tribune included responses that said comics “American sensationalism” would “make a child’s mind lazy” and that comics undermined “home, church, and school.”14 In 1954 the publication praised a conference called by the right-wing Attorney General of Alberta that demanded a ban on “crime, sex, horror, and war comics.”15

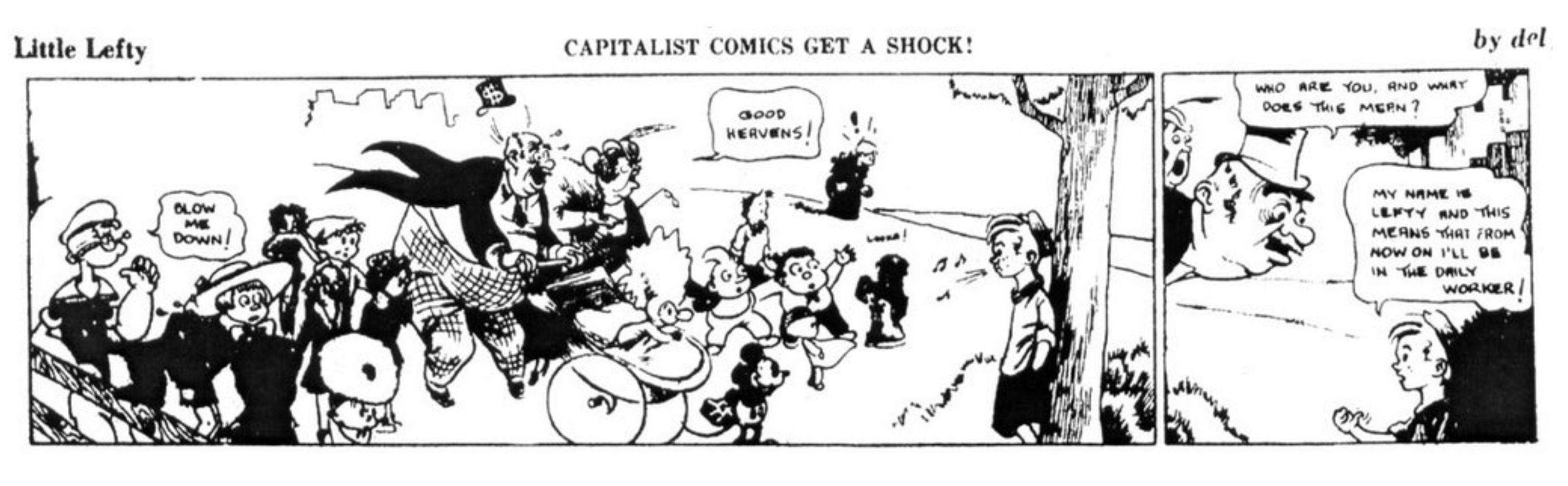

The Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), just like the Communist Parties of the other anglophone countries, was anti-comics. Interestingly, several talents from the Golden Age of Comics had connections to the CPUSA. Harvey Kurtzman, of EC Comics’ war comics and humor magazine Mad, had worked as an assistant for the cartoonist at the Daily Worker.16 As previously mentioned, Lev Gleason was a Communist Party member. Dick Briefer, who worked for a host of Golden Age companies including Harvey, Timely, and Lev Gleason Publications, also illustrated the Daily Worker’s anti-Nazi comic strip Pinky Rankin. Maurice Del Buorgo not only illustrated the Daily Worker’s Little Lefty (an answer to the right-leaning Little Orphan Annie) but also worked for DC Comics, drawing the Crimson Avenger and Green Arrow. Phil Bard, who was both an Abraham Lincoln Brigade (the Americans who fought fascism during the Spanish Civil War) veteran and illustrator for CPUSA’s gag comics in New Masses and the Daily Worker, also drew stories for superheroes Blue Beetle and Captain Marvel Jr. Bernard Krigstein, also of EC Comics and the organizer behind the first attempt to unionize the comic book industry, married into a family of Communists as his father-in-law was a party member and his brother-in-law was a Communist Party veteran of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.17

The CPUSA was actually relatively neutral towards comics in 1947, when they complained of the lack of racial and ethnic diversity in comics in the April issue of the New Masses. This brief mention focused on a political issue rather than condemning a whole medium or genre for aesthetic reasons.However, this New Masses article was an aberration. For as the 1950s commenced, the CPUSA began assailing comics vigorously. Three of these attacks appeared in the magazine Political Affairs. The first CPUSA complaint against comics appeared in the April 29, 1950 issue of Political Affairs under the article “Toward the Unity of Working Youth” by Leon Wofsy comics are scored for containing “anti-Soviet warmongering plots” and carrying “open appeals to chauvinism and violence”. The October 1954 Political Affairs article “On Patriotism and National Pride,” by Betty Gannett and V.J. Jerome, accused comics of being aspects of American culture that “true patriots” would not support, in language that seems cribbed from the conservative right. A final salvo against comics appeared in the November 1954 issue, in a review of the book The Game of Death-Effects of the Cold War On Our Children by Doxey A. Wilkerson. Wilkerson repeats the claim that comics are read mostly by children and that these comics, along with other popular media, contain “violence, murder, sex and moral degeneracy; and its dominant themes are anti-Communism and war.” Comics are joined by television, film, and radio in “a vast and profitable industry for the perversion of children.”

The CPUSA’s Daily Worker also assailed comic books. A May 13, 1949 article by Charles Corwin was titled “Comic Book Art: School for Sadism.” Another anti-comic book article appeared on Dec 10, 1952 entitled “100 Million War ‘Comic Books’ Yearly Feed War Propaganda to Children” by David Platt.18 The Daily Worker’s reputation for anti-comics sentiment was so well known that EC Comics publisher William Gaines used it in an attack against comic book opponents. The house advertisement “Are You A Red Dupe?” appeared in EC Comics’ staple of titles in which Gaines sarcastically compared anti-comics activists to Communists by quoting from a July 13, 1952 (the date is misstated as coming from 1953 in Gaines’ ad) Daily Worker article “It Ain’t Funny: Comic Books a Billion Dollar Industry Glorifying Brutality” which stated the role played by “so called ‘comics’ in brutalizing American youth to prepare them for military service in implementing our government’s aims of world domination.”

The Rest

This last group is for those who do not fit comfortably into either of the two categories above but are still on the political left and deserving of consideration. This includes Anarchists, New Leftists, and the broader strata progressives like the National Guardian. The National Guardian began as a newspaper supporting Henry Wallace’s 1948 Progressive Party presidential campaign, and its editorial line was very similar to that campaign’s platform, namely New Deal liberalism at home, and American-Soviet friendship abroad. Later, in the 1960s, the paper would move in a pro-Maoist direction. In a January 2, 1952 letter to the National Guardian, a reader ridiculed Lev Gleason for wanting to send comic books to the Soviet Union as a sign of friendship. The reader further claimed that American comics were “pseudo-scientific” and “instigators of juvenile crime in America.” In the May 3, 1954 issue of the National Guardian, a report appeared of Fredric Wertham’s testimony before the United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency. While the anonymous author stated that “children should be protected from a nightmarish view of the world as a reeling planet inhabited exclusively by green-faced ghouls, gunmen, ice-pick murderers, demented scientists and girls in bras consorting with over-sized gorillas” he does admit that the primary audience for this sort of material is adults, not children. The writer defends the earlier newspaper comics since they were comedic, and thus worthwhile but they condemn “the thrillers, chillers and killers of this generation” which are considered “mental pollution.” In the January 24, 1955 National Guardian, Ione Kramer wrote “The New Code: Will the Comics Be Cleaned Up?,” which reported on the new Comics Code Authority and its efforts to regulate comics. Unsurprisingly, Kramer was no fan of crime or horror comics, but a critique was made of the racist content of certain adventure comics, particularly the jungle comics subgenre. Kramer also said that comics continued to contain “bad printing and drawing; poor language and spelling; [and] the threat to good reading habits.” a fairly hypocritical argument given that this appeared in an issue of the National Guardian that also contained a political comic strip. In the June 1, 1959 issue, the National Guardian reprinted a political cartoon from the British Sunday Express in which children volunteer as strikebreakers because a longshoreman’s strike is preventing them from receiving a shipment of crime comics. As previously established, this was well after the heyday of horror comics so the reference is strange, but the ideology is apparent: that horror comics are so addictive that they will force even children to go against organized labor.

Anarchist writer Paul Goodman addressed comics a few times in his hit book Growing Up Absurd. He described them as “sadistic-sexual comic books” that could be best combatted through frank discussion of sexual activity. Like the above cartoon, this is an odd point given that comics had been “cleaned up” by 1960. In a March 1961 article in Anarchy titled “Sex and Violence and the Origin of the Novel,” British anarchist Alex Comfort repeatedly uses “comic-book” as a pejorative for literature he disdained. Finally, C. Wright Mills, the sociologist influential on the American New Left and author of The Power Elite referred to comics as “these ugly pamphlets” in a defense of Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent published in the New York Times. Like Evelyn Reed, Mills basically repeated Wertham’s arguments verbatim.

One maverick in the field of Marxist comics criticism, however, was C.L.R. James. James is placed here instead of under the Trotskyist category because even though he had been a member of both the SWP and the ISL, his politics were eclectic enough that, along with Raya Dunayevskaya and Grace Lee Boggs, he founded the Johnson-Forest tendency which split from both of these groups to chart a different course. In his 1950 book American Civilization, James defended the study of comic strips like Dick Tracy and Gasoline Alley, arguing for a positive view of the audience for mass culture against the elitism of many critics, stating “to believe that the great masses of the people are merely passive recipients of what the purveyors of popular art give to them is in reality to see people as dumb slaves.”19

Where Did It All Go Wrong?

Now that the statements of various left-wing groups and individuals on comics during the Comic Book Scare have been presented, the question must be asked how all these people and organizations got things so wrong. In my opinion, the anti-comics sentiment can be categorized in three ways, with various defenses (or lack thereof) for each.

The most indefensible left-wing argument against comics was against the comics form itself. This is epitomized in the 1952 article from the Militant, “Comic Strip Culture.” This argument was made hypocritically given that the Militant itself carried political cartoons that effectively combined words and pictures (good ones too, by Carlo and Laura Gray). The author never effectively argued why this combination was acceptable for a single image but unacceptable as a sequential narrative. Perhaps realizing how hypocritical this argument was, no other writers or publications repeated this argument.

The second major argument against comics was an aesthetically motivated opposition to certain genres. This can be seen in the repeated references to crime, horror, and war comics as being specifically harmful. This argument reveals a lack of imagination by the writers as they apparently cannot imagine a war story with a message against war or supporting a just war or a crime comic with a message against crime or a horror comic with any kind of message at all. This is particularly inexplicable given the existence of anti-war novels and films like Johnny Got His Gun or All Quiet on the Western Front at the time these articles were written. Jack Bustelo brings up the example of war comics with anti-war messages but never makes the connection that perhaps these were comics worth celebrating or defending as opposed to the other jingoistic, racist war comics. Likewise, gangster films like the 1932 Scarface or crime comics like Crime Does Not Pay could be said to preach against materialism and to have punctured the “American Dream” that hard work would breed success in a capitalist system. The fixation on horror comics is also bizarre given the importance of horror, not just in American culture, but in world culture. Some of the writers extended their opposition from horror comics to horror films, but the rest did not. Why? Why was it okay to go to a theater to see Dracula but not to read a vampire story in a comic book? Most of the writers don’t specify.

These criticisms based on genre also allowed the various socialists to ally with conservative or reactionary anti-comics forces. In Australia this was the Catholic Church, in Great Britain it was the Anglicans, in the United States it was churches and FBI head J. Edgar Hoover who said that comics were “crammed with anti-social and criminal acts, the glorification of un-American vigilante action and the deification of the criminal.”20

The final, and also the most defensible, anti-comics criticism was ideological. Sadly, this view was far less prominent than those which made attacks based on genre. The most sustained of these is Nora Emmett’s Socialist Outlook article, but occasionally political critique crept into other writer’s genre based criticisms as well. There certainly were plenty of ideological targets in comics that socialists could have focused on, from racist caricatures to the preponderance of benevolent rich heroes. Unfortunately, aside from Emmett’s article, the effect was lessened when these socialist writers repeated the same attacks made by the political right.

A notable absence in all of these articles is any sort of discussion about the creators of comic books. There’s no consideration as to the work that goes into these stories or if writers and artists have their own ideas, some of which might even be supportive of left-wing politics. Instead, if the creative process is considered at all, it is something done by the ruling class to push their agenda and these messages somehow spontaneously appear in comic books, without mediation by a writer or artist.

Another absence is the audience for comic books. When the comic book audience is described it is almost alway assumed to be entirely children or adults with some mental defect. It never occurs to these writers that some of these adults might be perfectly mentally sound and just have different tastes as to what constitutes entertainment. Given the millions of comic book readers at the time, many of these adults must have been working class and these leftists were alienating the very workers in whose interests they were claiming to speak through their pervasive cultural elitism.

Conclusion

Socialist and Communist anti-comics efforts and writing were widespread during the era of the comic book moral panic. There were differences of emphasis between different writers and speakers, but the most common critiques were against certain comic genres. Some critiques were political, but this was a minority. The overwhelming majority of criticism was that certain genres were bad in and of themselves, regardless of political content. The longevity of horror and crime comics’ use as a radical punching bag is surprising, given the bans and censorship campaigns. It’s as though the Communists, Trotskyists, and others had completely forgotten the earlier campaigns against comic books. There was even an anti-comics message in the SWP’s 1966 press release after the murder of their member Leo Bernard, by an anti-Communist fanatic in Detroit. The SWP stated that “over TV and radio, in the press and comic books, violence is shown and glorified day and night.” Even in the late-1960s, when tributes to Marvel Comics had been favorably profiled in “hip” outlets like the Village Voice and Esquire, the SWP and other leftists were still echoing the words of Fredric Wertham.

- Kent Worcester and Jeet Heer, Arguing Comics: Literary Masters on a Popular Medium (Jackson: University Press of Misissippi, 2004), xiv.

- Martin Barker, A Haunt of Fears: The Strange History of the British Horror Comics Campaign (London: Pluto Press, 1984), 24-25.

- Ibid, 138.

- Ibid, 20-48.

- George H. Pumphrey, The Comics and Your Children (London: Comics Campaign Council, 1955), 6.

- Ibid, 15.

- “Tragic Comics”, Tribune (May 24, 1950), 6.

- Rex Chiplin, “I Spent a Week in a Literary Sewer,” Tribune (November 11, 1953), 8.

- Mark Finnane, ‘Censorship and the Child: Explaining the Comics Campaign,’ Australian Historical Studies 13 no. 92, (April 1989), 229.

- Australian Journalists Association, Sin in Syndication: A Cultural Crime Wave That Threatens Australia (Sydney: Workers Press, 1949-1951), 3.

- David Hadju, The Ten-Cent Plague: the Great Comic Book Scare and How it Changed America (New York: Picador, 2009), 152.

- Joseph Tilley, “Pulp Fictional Folk Devils? The Fulton Bill and the Campaign to Censor ‘Crime and Horror Comics’ in Cold War Canada 1945-1955,” (Simon Fraser University, 2008), 64-65.

- Margaret Reeves, “Stop This Slow Poison.” Canadian Tribune (June 30, 1952), 14.

- Margaret Reeves, “Irreperable Damage,” Canadian Tribune (June 30, 1952), 14.

- Ben Swankey, “The Battle Against Those Yankee Crime Comics Gets Stronger,” Canadian Tribune (November 1, 1954), 9.

- Paul Buhle and Dennis Kitchen, The Art of Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of Comics (New York: Abrams Comic Arts), 3.

- Paul Buhle, “The Left in American Comics: Rethinking the Visual Vernacular,” Science & Society 71, no. 3 (July 2007): 351–52.

- Paul S. Hirsch, Pulp Empire: the Secret History of Comic Book Imperialism (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2021), 177.

- C.L.R. James, American Civilization (Oxford: Blackwell, 1950), 199.

- Hirsch, 178.