Alexander Gallus reviews Ilona Duczyńska’s German language book ‘The Democratic Bolshevik’ which explores the socialist experiment of Red Vienna and its failure to defend itself from reaction. Reading: Matthew Strupp.

After the destructive years of the First World War, social conditions in Austria were characterized by destitution and disorder. The conditions of the war, and the ensuing collapse of the Habsburg monarchy, created a crisis of state and authority rare in its scope and magnitude. The SDAP emerged from these conditions as the largest political benefactor. As Duczynska says: “There was only one authority which was strengthened and not destroyed, the SDAP.” 1 The Austrian Communist Party (KPÖ) had a membership numbering more than 6,000 after the fall of the First Republic in 1934; in contrast, the SDAP had over 700,000 members by 1929, more than ten percent of the country’s population.2

Striking workers and the masses of defeated soldiers formed councils in Austria, as they did throughout Europe in late 1918 after the signing of peace treaties. Located between the two tumultuous and now collapsed war fronts, the former Austro-Hungarian Empire saw countless weapons stream in from East and West. Consequently, the organization of self-defense groups became widespread and necessary in both cities and rural areas. Compared to their German counterparts the Social-Democrats of Austria were clearly more radical, with one of their most prominent members, Army Lieutenant Julius Deutsch, having been an organizer of a secret socialist military network within the Royal Army.3

In the summer of 1918, this socialist military network was created in order to prevent future military repressions of worker strikes. While the official authorities were in fact aware of this illegal network, they were not in a position, or were perhaps unwilling, to repress it. By the end of 1918, amidst popular rebellion, the network had successfully taken control of all the crucial military production and storage sites. The new State Secretary for the Army, Julius Deutsch, subsequently selected fellow Party member and Army Captain Eifler to protect the Arsenal, which was being protected by the previous spontaneously formed worker militias and councils.

On a different note, Duczynska offers insight into the attitudes of the SDAP leadership during this turbulent time of the council revolutions. Her principal view is that their attitude was a prototype of dismissal of councils (and left communism in general), and that the SDAP’s ‘foundational political sin was premature resignation.’ Interestingly, the SDAP, unlike most of the parties of the Second International, was intent on maintaining the unity of the workers’ movement, and was therefore permissive of its left wing. Radical locals and youth initiatives (such as the solidarity protests with Russia against the usurping Treaty of Brest-Litovsk) were not squashed by the bureaucracy as in Germany. By 1918, the majority of the SDAP, unlike their German brethren, were against the war. Whereas the 1918 January strike in Germany was organized by those who had been expelled from the German SPD for their opposition to the war, the January (Jaenner) strikes in Austria were victoriously led by the leaders of the SDAP. Pushing back against punishing half-rations for workers, longer work days, and so on, the successful ‘Jaenner’ strike movement set the confident tone for things to come.

After the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of Austria’s first Republic, the Entente demanded, as it did with Germany at Versailles, the disarming of all armed Austrian forces. Obliging not only for the sake of maintaining fidelity to democratic principles (the SDAP mass party had 40% of all votes in 1920), the Social-Democrats ordered all members of the army and militias to hand in their guns to the Arsenal. Austrian Heimwehr reactionaries, with their base in the organized and armed rural population, and the SDAP, with their base in the armed councils of urban workers, entered into a tentative agreement to keep arms behind lock and key. The crucial positions at these depots were, however, decidedly under the control of the Social-Democrats, protected by the traditional Party ‘Orderlies,’ rebellious soldiers, such as Deutsch and Eifler, and the organized workers. It is from this milieu and situation that the development of the SDAP’s paramilitary Schutzbund, or Republican Protection Association, emerged.

What makes Duczynska’s analysis, and Red Vienna in general, so interesting is the fact that the SDAP presided over the numerically strongest political and paramilitary organization in the country, but ultimately failed to take power. By 1934, the Schutzbund was twice the size of the Austrian Army, with twice as many members and more infantry weapons.4 This astounding fact raises the following questions: how did the working class lose against the fascist enemies of the Republic? How did Austria end up becoming part of the Nazi Reich? While an answer that encompasses all the historically contributive factors would be beyond the scope of this article, Duczynska’s answer is based on the defense of the critical views of former Army General Theodor Koerner. In 1924, Koerner became a member of the Austrian Social-Democratic Party, represented it in parliament, and acted as advisor to the Schutzbund, where he advocated for the professionalization of the organization.

While the SDAP’s right wing around Karl Renner was more often than not dominant, Renner’s main rival, Otto Bauer (the second most prominent Austrian Social-Democrat), was relegated to a lesser political role which amounted to phrase-mongering, radical agitation without serious political contention or preparation for revolution. An indicative example of the politics of Otto Bauer is the experience of the January strike of 1919: whereas the working class won reforms in the struggle against the capitalist state, Bauer warned of the might of the enemy, which was illusory, and overestimated the government’s strength. According to the internal review of the police chief of Vienna two weeks later, the state lacked sufficient means of exercising power and had insufficient troops to “suppress the widespread unrest”. 5 Both without and within, the armed forces of capitalism were overwhelmed by the forces of social upheaval and armed international communism.

With this in mind, Duczynska makes the case further on for the views of Koerner, who, in conversation with Ernst Fischer, stated, “I am a Democratic Bolshevik!” Her aspiration is to share Koerner’s vision of unifying the SDAP’s dedication to democracy along with the militant “statesmanly” politics of Bolshevism, that is, unlike Bauer’s castrated conception, a dedication to a ready and vigilant defense of democracy wherein the freedom of the working class to exercise its rights and historical mission is not violated at a whim. Common interpretations of Duczynska’s work appear to either focus on a marginal mention of hers that the Bolsheviks should have ‘maintained Otto Bauer’s commitment to democracy’, or assert that a revolutionary practice in the SDAP would have been impossible because unionized policemen were members of the Party. Neither of these two misleading characterizations actually engages with the content and possibility of the author’s focus, namely the dissenting voices within the SDAP and the vision of Theodor Koerner, eventual mayor of Vienna.

The ‘Manuscript’

By 1922, the political situation escalated with the victory of Fascism in Italy and the Catholic crypto-Fascism of Ignatz Seipel in Austria. The Social-Democratic Party and Schutzbund now stood openly on the ground of armed self-defense of the proletariat and consolidated the paramilitary organization of its orderlies. In reality, however, the essence of the organization did not change. It was still to be a mere instrument for the maintenance of the constitutional Republic and serve frequently, quite literally and physically, as a buffer between the rebellious working class and the brutal capitalist state. It did not, in the Social-Democrats’ majority conception, aspire, or even wish, to hone the physical prowess and experience of the many restless orderlies and worker militants in their youth for a successful and final fight against the declared enemies of democracy.

In his many speeches, Otto Bauer, the en essence political inheritor of one of the largest organizations of violence in the land, decried violence and warned the masses of the potentially frightful consequences of civil war. Here the ideological rift, which was to haunt the Schutzbund for its entire existence, began. Preceding Koerner’s entrance into the movement as advisor in 1924, a dissenting faction of the Schutzbund published what was to become known as the ‘Manuscript’ or Denkschrift. In it, the Arsenal protector Captain Eifler, his military staff, officers, and members of the Orderlies bemoaned the “dangerous attitude of the working class” towards military discipline and advocated for militarization within the Schutzbund, saying: “before all else, we must undertake a separation between Politics and the Orderlies. Only military command shall be the ruling standard [within the Schutzbund].” More importantly, the signatories bemoaned the Social-Democratic leadership’s lack of clarity on the concrete political goals of the movement, and ask in summary the question: “Do we want to simply bluff the Reaction, as we have so far, or are we intending to create an actual fighting group of the Proletariat?” 6

Deutsch, Rudolf Loew, Bauer, and others discouraged the drives towards military discipline in the organization and implemented a complex web of protocol for permitted paramilitary action, which largely stifled any dissent for a few years. Local Schutzbund paramilitary practices and actions required assent from local Party leadership, but also and not without the local Orderly leadership, with national Party leadership taking the minimum active responsibility. Effective exercise of defensive action was in fact not a primary concern for the Social-Democratic leadership in dealing with the Schutzbund. Military exercises and training, such as maneuver, hand grenade throwing, and shooting of various weapons were undertaken on a local and not systematic basis. Koerner’s forceful recommendations that the organization adopt a professional strategy inclusive of politically minded offensive action as well as a defensive one, and thereby seriously prepare the movement for civil war and survival, came into conflict with the dominant mindset which was concerned with not wanting to “provoke the enemy.” The reality, however, was that it was not the SDAP which was doing the “provoking.” Year after year, the strength and patience of the republican Schutzbund was tested by the capitalist state (through demoralizing weapon acquisitions), and Catholic fascists and Nazis (through street fights).

The Party, the Schutzbund, and the Critic

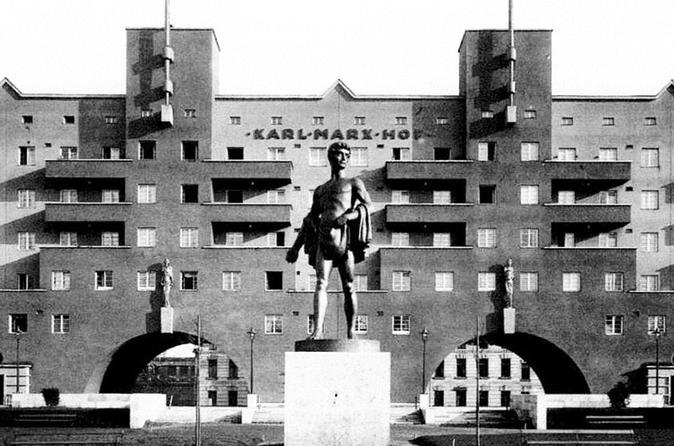

At this point, before further clarifying the critique of the Schutzbund and SDAP, it is important to recognize the very real accomplishments and significance of the Austrian Social-Democratic workers’ movement. Although its leaders did not dare to seize the moment of opportunity to overthrow capitalism in 1919, nor in 1922, thereby pushing the inevitable violent confrontation into the future, Austrian Social-Democracy claimed for the proletariat a quality of life which was unprecedented and still stands today as a historic accomplishment. The erection of urban worker housing, cultural and municipal government buildings such as the Karl-Marx Hof, free medical care, free dental care, and steep taxes on luxuries were more than reforms in the eyes of most.

A free and socialist press, which printed and distributed more material than was often read, accompanied the myriad of vibrant social-democratic cultural and athletic worker clubs. The powerful alternative culture of the working class in Vienna and other municipalities demonstrated without a doubt the self-confidence and independence of the working class. It demonstrated to the unbelievers before their eyes that, yes, in fact, the future can be built, and was being built. There was no question as to whether Social-Democracy was “building a state within the state.” As Duczynska recalls, anyone who lived through this time will “always remember those days and never forget them.”

It is also clear that without the powerful Social-Democratic Party (despite the cautious disposition of too many of its radical leaders), and without the serious character of its traditional paramilitary and Orderlies, the spontaneous councilist self-arming of workers after the Great War and the power of the proletariat would have remained a disunited and unclear one, as Duczynska acknowledges. The extent to which Otto Bauer and his colleagues were without political intelligence and dynamism is also severely called into question by the researcher Karl Haas. Nonetheless, Theodor Koerner waged a prolonged campaign of criticism through articles and personal letters to the “establishment” of the party. In a similar manner to the Schutzbund’s Manuscript critics before, but more extensively and precisely, the “General of Calm”, as he called himself, bemoaned the organization’s ‘political club’ culture and ‘parading that can only bluff.’ Basing his views on the writings of Clausewitz, Engels, and Lenin, he sought for years, in vain, to advise the party to utilize the instrument of the Schutzbund not simply for a fight, but for a successful fight. As Duczynska explains, crucially, Theodor Koerner believed in exploiting all possible legal means towards this end.

July 15th, 1927 as Turning Point

After reactionary Heimwehr members murdered a worker and his 8 year old child, the Justice Authorities in turn acquitted the murderers. Outraged by this injustice, social-democratic workers protested in the streets of Vienna and eventually set fire to the Ministry of Justice. In response to the escalating demonstration, the SDAP and Trade Unions declared a 4 day long general strike. Any efforts to prevent violence by the party and Schutzbund on site were in vain; as Gerhard Botz shows in his analysis of Red Vienna, with variable figures of domestic violence, unemployment, and police violence, a violent confrontation at that time was inevitable. 7 Attempting to form the usual barrier between police and protesters, Schutzbund members saw and felt, quite viscerally, this day to be different.

Amidst stones hurtling overhead and blunt instruments swinging their way, not a few troops wished to be armed with more than their silly fencing sabers. The police assembled with clubs, swords, and revolvers on horseback. The organized demonstration developed, on the basis of the growing social crises and class tensions, in the course of the day into an outright riot, with workers eventually preventing firemen access to put out the Ministry fire. Consequently, the police chief armed the police with old war rifles; they trampled, cut, and shot, with weapons intended for war, hundreds of proletarians.

For five deceased policemen that day, 89 demonstrators were killed and over a thousand individuals were injured. Defeated and deeply humiliated, Schutzbund members ran to the leadership, begging for the unleashing of the Arsenal to arm their comrades and the proletariat. Abused workers ran through the streets with tears and asked the Social-Democrats for arms. Contrary to what some critics assert, these pleas did not fall on deaf ears, and the Social-Democratic leadership decided to expedite the militarization of the Schutzbund. The effect of the defeat, while not reflected in electoral terms (quite the opposite), was a decisive blow to the morale and hope of the strongest elements of the proletariat. It was crucial in preparing the ground for the emboldening of fascism, as fascism feeds off the ground of cynicism and despair.

The Schutzbund’s militarization then developed in accordance with the views of the established Arsenal protector Eifler. While the Eiflerian militarization could be considered progress, and promisingly showing signs of holding the political leadership accountable to the Party’s 1926 Linz Program stated goal of building a ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’, this alone reveals the real issue: it was the political leadership which had to be pushed by events and the membership to take on more initiative and responsibility. As Clausewitz teaches, and Koerner made searingly clear in his writings, war (‘here, civil war’) is politics through other means — it is, consequently, intimately tied in its success or failure to the ability of the political leadership to set strategic goals and successfully communicate them to and within the military (or paramilitary), ‘down to the last man’. A political leadership that shirks these necessary responsibilities, desiring only to appeal and not to win, is less a driving force forward than it is a stick in the spoke of a wheel.

In the eyes of Koerner, the professionalization of the Schutzbund was not in the least in contradiction with democratic principles, flourishing worker civil organizations, and independent party politics. Furthermore, it and it alone, with 80,000 troops and 700,000 party members behind it, could guarantee the survival and victory of the movement with social tensions that could not be resolved peacefully within capitalism. Based on studies he conducted of the international worker movement’s military experience, Koerner published numerous articles addressed to the workers of Austria in support of a strategy that can be summed up as urban guerrilla warfare. Appearing in both the Schutzbund magazine and other party journals, with arduous effort, these articles quote throughout from the Russian Social-Democratic fighting group’s learned experience in the 1905 revolution, highlighting the importance of multiplicitous and small fighting groups, quick attacks and equally rapid escapes, and conducive and impermanent surroundings/dwellings for proletarian soldiers.

From this it is clear to see that, instead of espousing the party-dominant ‘defensive’ politics, Koerner advocated for the ready utilization of attack against the growing forces of capitalism and fascism beside defense, as in the escalating days of July 1927 and later. In a critique of Eifler’s plans for inconsequential territorial and defensive military actions in Vienna, Koerner addressed a letter to Otto Bauer in 1930 that threatened his resignation if he was not allowed leadership of Schutzbund policies. Underlying the multitude of criticisms of how the Schutzbund was being run was a basic, yet educated, military common sense as to the rigorous demands and necessarily centralized structures of an army.

Having been pushed into the background since 1927, Koerner finally resigned from his posts in 1930 and criticized both the Second International for having an incorrect calculation of the fundamental questions of violence itself, and the Third for its “untimely tactic of the street fight.” 8 After a last ditch attempt to steer the movement from its course, Koerner wrote a letter to the ‘realist’ Social-Democrat Karl Renner in 1933. But by the time Koerner was invited by Bauer and the other Social-Democratic leaders to take a hand in things at the beginning of February 1934, it was too late. Two weeks later, the already de facto illegal and deformed Party saw its secret weapon depots now confiscated in the largest police campaign and provocation yet.

Resistance to the weapons acquisitions and illegalization of the SDAP lasted for four days and ended with perhaps up to a thousand Social-Democrats and Schutzbund fighters killed. To their credit, the Communists and autonomous groups offered some of the strongest resistance in February and led the resistance first under Dollfuss and then under Hitler. Half the positions of Koerner’s city government after the fall of the Third Reich were to be filled by representatives of the KPÖ.

The idea of victory, the only possible way of saving the First Republic, was more feared by the Social-Democratic leaders than losing was. Winning requires courage and ready answers to the countless difficult questions of creating a new society. Otto Bauer’s conception of the Schutzbund was retrospectively summed up aptly by a trial witness in 1935, saying: “Bauer believed that the fight would not be spared the working class. The Schutzbund was the crutch of the Party, but it alone can do nothing, one must bring the working class to spontaneously go with the Schutzbund.” 9 Even Ilona Duczynska, who strongly sympathizes with the autonomous Communists of the 1970s, sees the unfortunate dark irony of this “paradoxical” political leadership.

A curiosity when reading Duczynska’s positively engrossing book about the Democratic Bolshevik is that, despite the fantastic research with wide-spanning correct and insightful observations, there is the gap between the assertions and their logical conclusion. While Koerner’s criticisms and proposals were sound, the fact is that he failed to win political support for them for fear of discrediting the leaders of the movement and creating disunity in the party. One can’t help wondering why Koerner acted in the way that he did, writing fruitless letters for years, if he understood the truthful weight and strategic importance of his criticisms at that time.

On the fateful days of the July fights in 1927, Koerner was out on the street as a loyal party soldier trying to avoid a full-blown civil war. Koerner, in this instance, was not wrong however: the working class, Schutzbund, and Social-Democracy were not prepared to win a civil war before the background of the mobilizing Heimwehr and full capacities of the state. As authoritative historians such as Botz and Charles Tilly make clear, the Schutzbund was, in its own imposed framework, doomed to fail against the axis of Austro-fascists.10Norbert Leser’s view that Austro-Marxism was destined to fail because of its determinism is more than accurate. As Duczynska makes clear, the historical determinism of Bauer, Deutsch, and the right wing (to the extent that it truly desired socialism) was not limited to the right and ‘center,’ but was a problem even more so with the left of Austrian socialism. Theories and hopes of spontaneity more often than not have historically served as handy rationalizations for a personal aversion to the necessary decisions of responsibility.

The General’s failure, and one should perhaps respectfully hesitate to loudly declare it, was in not calculatingly exploiting the multitude of political crises and humiliations of the SDAP for a public and party opposition to the indecisive leaders of Social-Democracy. In order to win such a daring ‘battle of democracy,’ one must first make one’s opinions loudly known and far-reaching. This facet was unfortunately not a personality trait of Theodor Koerner, who was, to use his own words, a quiet ‘military technician’ and humble advisor. After two spells of imprisonment, one under Dollfuss in 1934 and then under Hitler, Koerner, the ever loyal party servant, served as Vienna’s mayor during its process of rebuilding after WWII, and as Austria’s President from 1951 to 1957.

- Duczynska, Ilona, Der Demokratische Bolschewik. pg. 57

- Kirk, Timothy, “Nazism and the Working Class In Austria”, pg. 32

- Duczynska, Ilona, Der Demokratische Bolschewik. pg. 53

- Duczynska, Ilona, Der Demokratische Bolschewik, pg. 41

- Duczynska, Ilona, Der Demokratische Bolschewik, pg. 61.

- Duczynska, Ilona, Der Demokratische Bolschewik, pg. 76-77

- Botz, Gerhard, “Die ‘Juli-Demonstranten’, ihre Motive und die quantifizierbaren Ursachen des ‘15. Juli 1927’”

- Duczynska, Ilona, Der Demokratische Bolschewik, pg. 166

- Duczynska, Ilona, Der Demokratische Bolschewik, pg. 113

- Botz, Gerhard, “Die ‘Juli-Demonstranten’, ihre Motive und die quantifizierbaren Ursachen des ‘15. Juli 1927’”