Daniel Tutt writes on German Marxist Ernst Bloch’s engagement with the Islamic scholar Ibn Sina and its potential for revitalizing materialist philosophy.

The Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch was marginalized in his own time, branded a renegade idealist by the Stalinist regime, exiled in America from the Nazi war machine, and barred from the Frankfurt School for views that were “too communist.” But his thought has continued to gather interest in 21st century Marxist and philosophical circles due to both the reemergence of theological interest within Marxist thought, and a turn to speculative materialism in continental philosophy starting in the early 2000s. Although his works The Spirit of Utopia (1918) and The Principle of Hope (1954) are widely read today, a number of his most important works remain untranslated from German. This untranslated corpus includes his three-volume Das Materialismusproblem that examines both the history of materialism and Bloch’s innovative synthesis of Hegel, Schelling, and Marx.

Among Marxists Bloch is well-known for his writings on the idea of utopia. Bloch analyzes historically this concept in pre-capitalist religious egalitarian movements such as Thomas Müntzer’s medieval peasant’s rebellion, and in social formations that reflect partial and anticipatory consciousness of emancipation. How Bloch theorizes utopia and the principle of hope from a distinctive Marxist and historical materialist orientation is best understood by a distinction he offers in Principle of Hope, a book written in exile in America. There, he posits two dominant strains of Marxism: the cold-stream and warm-stream. The cold-stream is analytical and concerned with the unmasking of ideologies and the disenchantment of metaphysical illusion, that is, a ruthless critique of existing oppression. The warm-stream is the “liberating intention and materialistically humane, humanely materialistic real tendency, towards whose goal all these disenchantments are undertaken.”1

Bloch theorizes the two strains not as separate poles working in isolation, but as a necessary synthesis. He insisted that the coldness and warmth of concrete anticipation taken together ensure that “neither the path in itself, nor the goal in itself, are held apart from one another undialectically.”2 Bloch thus sought to embed historical materialism in these two streams while recognizing that the warm-stream was often ignored and marginalized in Marxist practice from Marx’s own time to the present. We should understand these two strains as both an epistemological and a praxis-based distinction. Unlike the analytic cold-stream, which is often exclusively concerned with economic analysis, the warm-stream is concerned with the ways in which the “debased, enslaved, abandoned and belittled human beings” make appeals of emancipation. The warm-stream points to what he calls a “homeland of identity, in which neither man behaves towards the world, nor the world behaves towards man, as if towards a stranger.”3 The warm-stream is thus the utopian revolutionary imagination which can only be fully achieved from the vantage point of a classless society.4

The warm-stream can also be read as a form of secular religious conversion involving a commitment to human emancipation. Such an idea of Marxism as a conversionary experience is articulated by the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk’s in You Must Change Your Life (2009). Here Sloterdijk argues revolutionary socialist and communist movements proposed a model of conversion based on the necessity of man to develop a new awareness of the ‘vertical axis.’ Playing on the immanent-transcendent distinction, Sloterdijk names the vertical axis that axis by which the sacred, like the transcendent, is concerned with occupying what religious belief formerly occupied. The communist revolutionary is not concerned with furthering morality as religious morality understood it, rather, as Sartre said, “true morality is a permanent conversion into revolutionary action.” Such a conversion into revolutionary action is occupying the same axis that religious conversion and religious truth formerly occupied. Sloterdijk analyzes the October Revolution in Russia as an event that turned revolution into a spiritual event. While conversion typically means spiritually re-setting one’s life, revolution means redesigning the world from zero; and the Bolsheviks combined these two forms in a spiritual revolutionary conversion. But, according to Sloterdijk, revolutionary conversion is no longer efficacious after May ’68 because revolutionary movements have continually failed to transform everyday life. Thus, to “become a Marxist” or to gain a commitment to revolutionary action no longer not implies the same consequences precisely because revolutionary change has become an individualized ascetic routine unable to produce a fundamental revolutionary event or overthrow of existing conditions. Sloterdijk’s idea of communism as an ascetic life practice akin to religious conversion is compatible with Bloch’s idea of the warm-stream as the collective yearning towards emancipation implicit in historical religious movements.

Materialism and the Warm-Stream

Warm-stream Marxism is concerned with collective movements of emancipation and with understanding the upsurge of human freedom not as a completed state, but with a linking of this desire to a consideration of matter in a perpetually transformed state. The function of matter and materialism within warm-stream Marxist thought is in many ways the launching point of Bloch’s speculative philosophical thought. Cat Moir, in her superb book on Bloch’s materialism Ernst Bloch’s Speculative Materialism, shows how Bloch in his trilogy “Das Materialismusproblem” develops a concept of matter as the self-realizing impersonal agent of nature. According to Moir, this untranslated work is a bridge to understanding Bloch’s more widely read work on utopia and the Principle of Hope. Moir shows how for Bloch the very possibility of utopia resides in matter itself, and how human beings as “matter-become-conscious” beings are capable of realizing it.

Bloch’s wider work on materialism was never translated into English due to Stalinist censorship, and because of the assumption amongst many party functionaries that Bloch’s materialism was idealist. Moir shows how Bloch’s materialism was far more complicated than this accusation, and that while he argued that rethinking materialism must be begun again and again, he insisted that any consideration of materialism must involve “inviting all kinds of earlier voices,” including idealist thinkers from Plato and Avicenna to Kant and Hegel. Bloch perceived Hegel’s synthesis of substance and subject as resulting in an idealist fantasy world of pure anamnesis, and he thus refuted such a synthesis by isolating substance (matter) as a fundamentally incomplete process. In his later work Bloch accuses Hegel’s system of excluding real possibility, of thinking possibility as tied up with past historical cycles such that what we come to know must already have existed prior to our knowledge of it. It was this sense that Hegel’s dialectic and wider philosophical system foreclosed real possibility that led Bloch to consider Schelling’s ontology more closely, and to also engage in a genealogy on matter and materialism that stretched back to pre-Aristotelian Greek philosophers. Bloch’s materialism was open to idealist strains of thought—Schelling, Aristotle, Ibn Sina and Hegel—and he read metaphysical and mystical traditions as supportive of egalitarian conceptions of the cosmos and humanity. As the prominent translator and commentator on Bloch Peter Thompson argues, this interest in religious metaphysics was Bloch’s attempt to “search for the materialist base within the metaphysical apprehension of the religious worldview.”5

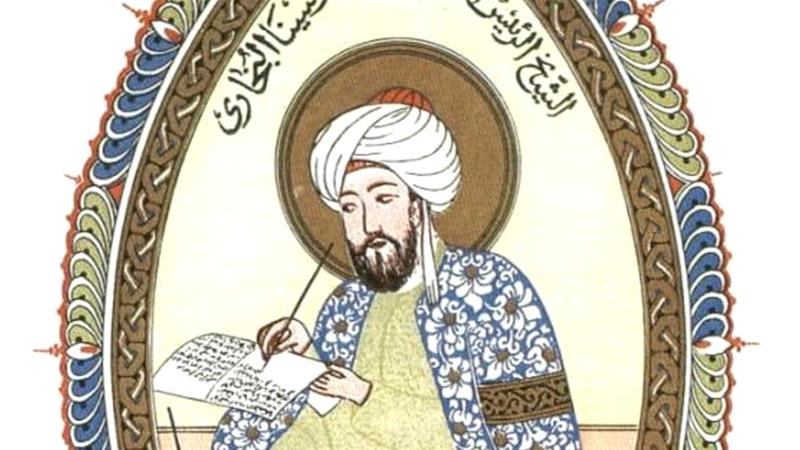

In the recently translated work Avicenna and the Aristotelian Left (2019), originally written as an appendix to his work on materialism, Doctrines of matter, preparations of its finality and openness, Bloch finds in Avicenna (the common European name given to the Islamic philosopher Ibn Sina) a crucial origin point to leftwing and emancipatory thought. In what follows, I aim to describe Bloch’s interest in Ibn Sina by shedding greater light on who Ibn Sina was for Islamic thought and for philosophy writ large, as well as to identify some of the important themes his thought offers to the tradition of warm-stream Marxism.

Ibn Sina’s Metaphysis and Wider Importance

Ibn Sina’s metaphysics and influence on Islamic and Occidental thought is nothing less than extraordinarily significant. Philosophically, Ibn Sina fuses Aristotle with Neoplatonism, arguing that existence is an accident and, as such, there is no existence implied in any essence. If a thing does not exist, it does not have an essence to cause it. By extension, before a thing exists it does not have a nature (or pre-determined essence) to determine it. Ibn Sina argues that existence is accidental to essence and therefore no contingent being is rid of contingency. The only self-sufficient being is God and from God’s self-sufficiency stems the contingency of the world, for nothing else could be necessary. Lenn E. Goodman, a well-known commentator on Ibn Sina shows how his idea of the cosmos was based on a theory of predestination even though he adopts a view that all matter is contingent. That is, there is still a necessary being (God) which determines the universe, although existence is radically contingent. Goodman argues the emphasis Ibn Sina placed on necessity amidst radical contingency resulted in a profound set of misunderstandings with other Islamic theological and philosophical critics. For example, the Ash’arite school argued that all causal determinations are vertical and external: every leaf that falls from the tree is determined by God. But in Ibn Sina’s view, God allows created beings to determine events for themselves.6

Ibn Sina also put forward a Platonic concept of God as one who is perfect and therefore beyond sensory experience, and combined this argument with an ontological argument based on a necessary absolute ontic7 existence of God. Since matter cannot exist without form, Ibn Sina argues that the matter of the world is eternal. But although matter is eternal, existence is an accident, which means that essence is not implied in anything necessarily. Because existence is prior to essence—both logically and ontologically—God bestows existence on things, that is, God gives form to matter but matter is mediated by the Aristotelian idea of the “Active Intellect.” Ibn Sina has a nontemporal view of creation based on the absolute act of creation—just like existence is contingent, so too is creation. Through man’s rational faculties and capacity for reflection and speculation humans can enter into a rational recognition of necessity. As Goodman writes:

The life that animates the heavens and becomes the paradigm and ultimate engine or energizer of the processes of nature is the product of the rational recognition of necessity.8

Ibn Sina’s metaphysics are thus radical in their emphasis on the incomplete and permanent contingency of matter and existence, as well as in the way he theorizes the Active Intellect as a source of the emanation of a communal collective truth that links man’s rational contemplation to God. Ibn Sina’s metaphysics are based on the metaphysical proposition of a synthesis of eternity with contingency, and as we will see when we turn to Bloch, much of this is in line with Bloch’s metaphysics. Although Bloch conflates Ibn Sina with Ibn Rushd (Averroes), a later and important Muslim philosopher, it is important to note that Ibn Rushd objected to Ibn Sina’s more radical idea of contingency. Ibn Rushd argued that contingency of all beings must be understood by the reference to an idea of causality if it is to reach the implication of an external cause for the object we see before us, because otherwise we have an infinite regress of causes.

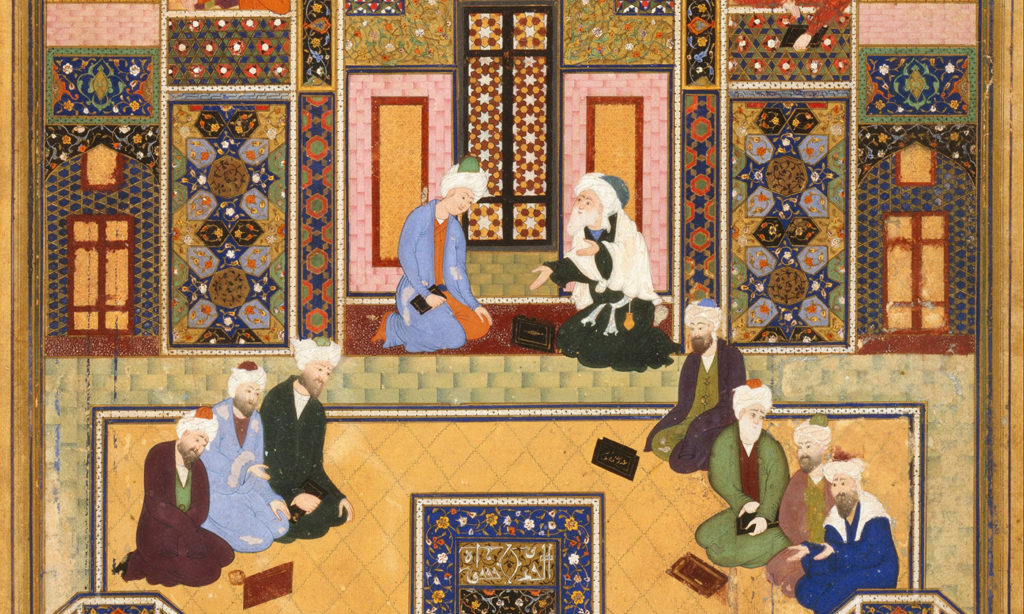

Outside of Ibn Sina’s metaphysics, it is worth noting that Ibn Sina’s influence is widespread although a matter of some controversy amongst scholars. For example, in the recent masterwork by Islamic scholar and the late academic Shahab Ahmed, What is Islam: The Importance of Being Islamic, Ibn Sina is presented as “the man who effectively defined God for Muslims.”9 Ahmed identifies Ibn Sina as the thinker who emerges in the far east of the Islamic empire (modern-day Uzbekistan) in the 10th century (350 years after the Prophet Muhammad died) and grows to become the seminal theologian-philosopher that defined the “Balkans to Bengal complex” of Islamic societies. The Balkans to Bengal complex was a distinctive social and cultural expression of Islamic civilization that spanned a geographical territory and imprinted an entirely novel form of Islamic community, with Ibn Sina’s contribution to this complex being fundamental.

For Ibn Sina, the soul does not live on after death, but is purely a vegetative state; a natural organ. As a result, the eternal torture of the soul, held to be a doctrine in much of Islamic theology, is off the table as is eternal damnation. This idea led to a new concept of the self as formulated through self-knowledge. Ibn Sina’s work grew so much esteem that the elite educated classes adopted the study of philosophy within the madrassah educational system largely due to his influence. Ibn Sina’s influence also opened an entirely new way of thinking about the role of wisdom hikmah in relation to the divine. Hikmah became a source for navigating universal truths in societies of Muslims. Philosophical wisdom was both the enactment of practical rules and theoretical rules consonant with those values. Ahmed writes:

Ibn Sīnā conceptualized God as the sole Necessary Existent (wājib al-wujūd) upon which all other existents are necessarily contingent. It is this philosophers’ conceptualization of God that became the operative concept of the Divinity taught in madrasahs to students of theology via the standard introductory textbook on logic, physics, and metaphysics which was taught to students in madrasahs in cities and towns throughout the vast region from the Balkans to Bengal in the rough period 1350–1850, and which was tellingly entitled Hidāyat al-ḥikmah, or Guide to Ḥikmah.10

The Aristotelian Left

Unlike Aristotle, who sees matter as passive and inert, Ibn Sina views matter as possibility in the sense of a complete disposition to receive forms. He argues that philosophical truth contains the truth just as does the Qur’an, but it is hidden behind a veil.11 Allah (God) is the inflowing of nature itself for Ibn Sina, and based on his idea of contingent matter he sees the whole of nature with an accent of monist tension. For Bloch, Ibn Sina discovers something seminal in Aristotle’s Metaphysics and gives birth to the “Aristotelian left”, because he posits that matter is a natural and dynamic (dyname) thing. This “left” is unlike the Aristotelian “right”, which is most notably represented by St. Thomas Aquinas who refused to think of matter as capable of changing itself. From the premise of matter as a fundamentally contingent and dynamic process, Ibn Sina would develop a theory of the Active Intellect beyond an idea of mere individual moral reflection, but as part of a process of universal reason connected to the community.

Bloch notes that Ibn Sina understands the “unity of the human intellect and the unity of active reason” and this understanding posed a profound challenge to both Christianity and to Islamic orthodoxies because it portended the application of this principle beyond the bounds of the religious community. Ibn Sina thus opens the way for a radical form of tolerance across communities by his idea of the Active Intellect. Bloch further observes that the influence this universal reason had on influencing a “new pathos of tolerance” is connected to his idea of the warm-stream horizon of hope we identified earlier. It is also connected to Thomas Müntzer, who declared human freedom on the basis of the new universal reason.

The most technical contribution Ibn Sina made to philosophy was thus what he said about the wider matter-form debate within Aristotlian scholarship. It is clear that Aristotle’s idea of matter was one that taught matter was in the first place something completely indeterminate and unformed, itself uncreated, but out of which all things can be created. What Ibn Sina gives to Aristotle’s idea of matter is the “notion of ferment, self-creation and the sheer incompleteness of this possibility.”12 This insight loosens the bonds between being and matter and enables the philosopher to think of the explication of the world out of itself. This immanent view of matter and the possibility of worldly redemption is far afield from the right-wing Aristotelians under St. Thomas who posited “a fully transcendent theism of pure spirit.”13 Aquinas removes that which realizes forms itself (entelechy) and relegates this act to an exclusive gift of the divine Act-Being, the Being of realization, and subordinates it to the totally transcendental. Influenced by Neoplatonism, Ibn Sina secured the contingent existence of things from a necessary divine being, and as such his vision of the cosmos is one in which God allows the universe to remain radically contingent. Aquinas, on the other hand, says that the essence of God can be nothing other than his being, guided under the maxim, “I will be what I will be.” This conservative metaphysics makes becoming devoid of any future dimensions. Ibn Sina thus made way for philosophers such as Spinoza who would argue that the essence of religion is not dogma, but praxis in the world.

Since matter conditions everything in Ibn Sina’s metaphysics, matter is both potential and potent. Matter has to move, due to its innate propensity towards the realization of that which is not-yet become. This idea of matter is hugely influential on warm-stream Marxist thought in two ways: firstly, it enables an aesthetic idea of realism and artmaking quite distinct from socialist realism of Bloch’s time. As Karam AbuSehly has shown, Bloch’s reading of Ibn Sina influences his own ideas of aesthetic realism, where attention is paid to the object in itself, unlike in idealist aesthetics.14 In addition to influencing Bloch’s theories of aesthetics and realism, Ibn Sina’s concept of matter also influenced his ideas on utopia. If utopia is fundamentally covered in darkness in the sense that it cannot be pictured; it cannot be named. It is the thing that is missing, and accordingly utopia puts matter in motion for its realization and the realization of itself. The philosophical and materialist genealogy Bloch provides us is an indispensable resource for understanding the warm-stream of Marxist emancipation, and it helps us broaden our relations to religious discourse both historically and in the world today.

- Bloch, Ernst The Principle of Hope MIT Press, Boston, MA, 1998. Pg. 209

- Ibid., 209

- Ibid., 209

- Ibid., 209

- See Peter Thompson’s introduction to Bloch’s Atheism in Christianity: The Religion Of The Exodus And The Kingdom (2009). Pg. X

- Goodman, Lenn E Avicenna Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 2006. Pg. 89

- Ontic here refers to a real existence not merely a phenomenal or nominal existence.

- Ibid., 89

- Ahmed, Shahab What is Islam: The Importance of Being Islamic Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2016. Pg. 19

- Ibid., 19

- Bloch Ernst (translated by Loren Goldman and Peter Thompson) Avicenna and the Aristotelian Left Columbia University Press New York, NY 2019. Pgs. 12 – 14

- Ibid., 21

- Ibid., 25

- Karam AbuSehly, “Avicenna on Matter: Implications for Ernst Bloch’s Aesthetics” ReOrient 3.1, Pluto Journals