Ben Reynolds responds to Chris Koch’s The Need for Agitational Organizations.

In a recent article titled ‘The Need for Agitational Organization’ Chris Koch argues that the lackluster growth of revolutionary organizations can be attributed to their petite bourgeois class composition, fetishization of leadership, and ideological rigidity. Koch is right that the predominantly middle-class membership of most left-wing organizations, along with their white and male skew, is a serious obstacle to future growth.1 However, today’s fundamental barrier to positive change is not just an insufficient focus on agitation, but the lack of real knowledge of basic organizing techniques and effective campaign strategy. We have organizations that sell newspapers, call for demonstrations, conduct political education, create podcasts, and infight – we do not, on the main, have organizations that spend their time organizing.

What actually is “organizing?” Members of many leftist organizations would be hard-pressed to find leaders who could give a convincing answer to this question. Indeed, one would probably hear a laundry list of the sort of activities described above which, while important in one way or another, are not organizing. Organizing is the building of relationships with members of an oppressed class in order to create a structure that will enable the group to collectively fight for its interests. It is externally focused, oriented toward uncontacted individuals outside the group who need to be engaged in struggle. By contrast, most left-wing organizations spend their time mobilizing existing members and contacts to come to meetings, attend protests, donate resources, and so on. Because the membership of these groups is predominantly middle class, individuals who happen to join due to existing friendships and chance social connections also tend to be middle class, perpetuating social isolation.

There are a number of reasons that organizations tend to prefer to do pretty much everything except external organizing. First, deliberately trying to forge relationships with new people can be intimidating. It is much more comfortable to spend our time with the already-convinced and with our current friends – the social alienation created by today’s media technologies has exacerbated this problem. Second, organizing is difficult. It requires many hours of work over a relatively long period of time to canvass an area, build relationships with key individuals, and mobilize a community to take action. It is certainly easier to promote a demonstration on social media to the same group of people who show up to every protest.

However, the most important reason for the blockage is that many left-wing organizations have little-to-no knowledge of how to actually undertake an organizing campaign. This is a product of historical circumstances. The defeat of the radical movements of the mid-20th century severed the institutional transfer of knowledge from experienced activists to new members. Leaders of organizations like the Black Panthers were assassinated or imprisoned; student radicals were largely co-opted and reintegrated into capitalist society. Each new generation of activists has thus had to learn the practices and pitfalls of movement work largely blind, with minimal guidance from elders, and has engaged in the same patterns of activity: an influx reacting to an external challenge, symbolic protest action, media coverage and growth, impasse, stagnation, and decay. As burnt-out activists leave in the final stage, so too the knowledge of successes and failures departs from the movement.

Where there are pockets of knowledge about organizing strategy and techniques, the connection to left-wing groups is often insufficient. For example, there are relatively few linkages between organizers in unions that still effectively recruit new members – UNITE HERE and National Nurses United, for instance – and the revolutionary movement. The same can be said of the few nonprofits that focus on base organizing rather than ‘advocacy’ and lobbying. This is not a fatal limitation in and of itself. To overcome it, organizations need to systematically train new members (and, given the present state of things, existing members) on how to become effective organizers. They need to develop training programs, methods for experienced individuals to share skills, and processes of evaluation and self-criticism to allow effective techniques to spread. Most importantly, they must undertake campaigns that put these skills to use, allowing organizers to develop their abilities through practice while recruiting working-class leaders.

While this is not the place for a manual on external organizing, it is still important that we have a basic understanding of what an effective organizing campaign looks like. A campaign begins by identifying a group of people who are being exploited by a shared enemy – a company, landlord, police agency, etc. The organizers must map and canvass the area to understand its social groups, points of agreement, and potential schisms. They must also identify points where the community can exert strategic leverage by inflicting meaningful costs, in dollars, on the adversary, as in a labor strike, rent strike, or blockade. Finally, the organizers need to identify the organic leaders within the community who can help move their social groups to take action when necessary.

The organizers must develop relationships of trust with these leaders and other members of the community, listening to and understanding their problems and motivations. They must then use their understanding to help these individuals overcome their fear and decide to take action. The organizers and community leaders then mobilize a critical mass in the wider community to join the struggle, conduct a pressure campaign against the adversary, and force concessions. Through this process, trust between the organizers and community is created, the oppressed discover their strength, and effective working-class leaders are identified and tried by fire. In one such example, recent organizing by Stomp Out Slumlords in D.C. has led to rent strikes and the creation of a city-wide tenant union.

Chris Koch correctly stressed the importance of credibility, which could be more simply stated as a problem of trust. Working-class communities do not even know that most left-wing organizations exist but, if they did, they would still need to trust them to be willing to risk the real consequences of taking action. Agitation alone is not enough to create this trust. Standing on a soapbox and delivering stirring oratory is no substitute for the relationship building that has to take place before mass action is possible. Agitation, in this context, is more likely to happen over a beer or in someone’s living room than at a major demonstration – it is the part of the process where an organizer helps someone overcome their fear with the dual motivations of hope and anger.

Internal democracy, charismatic agitation, and ideological flexibility are all important – but they are mere window-dressing if an organization has no mass base. The truths of revolutionary socialism will find no purchase if there is no one to listen to them. And, to be frank, the movement needs to spend much more time listening to the problems and demands of the working class, and a bit less time preaching its chosen truths.

Workers like Alexander Shlyapnikov joined the RSDLP and later-Bolsheviks because they developed contacts with members who fought with them in their concrete struggles. Koch rightly emphasized that worker-leaders like Shlyapnikov were far more effective at convincing other workers to take action than socialist intellectuals. Workers in a UPS logistics center, for instance, are still far more likely to listen to their compatriots then some college student radical off the street. This is true of social groups in general – imagine your reaction if a Democratic Party operative tried to advise your local leftist group on the actions it should take. Again, the only way to overcome the social barriers between insiders and outsiders is to undertake a concerted effort to build relationships with insiders, face-to-face.

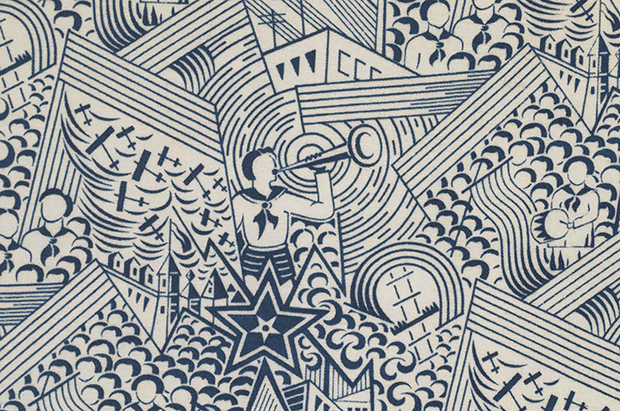

I believe we need an organization today that somewhat resembles the IWW of old: a big tent comprised of anarchists, communists, socialists, and other militants who unite first and foremost around practical organizing work aimed at engaging the oppressed in struggle and building the organized power of the working class. Unlike the old IWW, such an organization would also engage in campaigns beyond syndicalism, supporting the struggles of tenants, prisoners, the LGBTQ community, and so on. Whether existing organizations can adapt themselves to the task at hand, or whether such a new “people’s alliance” is required, remains to be seen. If the revolutionary movement does not root itself predominantly in the working class, it will fail, plain and simple. It is up to those of us who recognize this reality to side-step the more irrelevant debates within the movement and take up the serious work of creating a movement that organizes.

- There are a number of reasons why the DSA has outpaced other organizations, but class composition is not one of them. The overrepresentation of middle-class, white, and male elements is endemic to left-wing and radical organizations, including the DSA. It has succeeded for the following reasons: it is an open membership organization; it is a big tent that accommodates multiple ideological strains; it has developed links with important unions and other organizations; it was and is associated with the Sanders campaign; it is engaged in practical work, even if that work is uneven; and it has an articulated strategy that seems reasonable to its members and newcomers.