Introduction and translation by Tom Anderson. Original article can be found here.

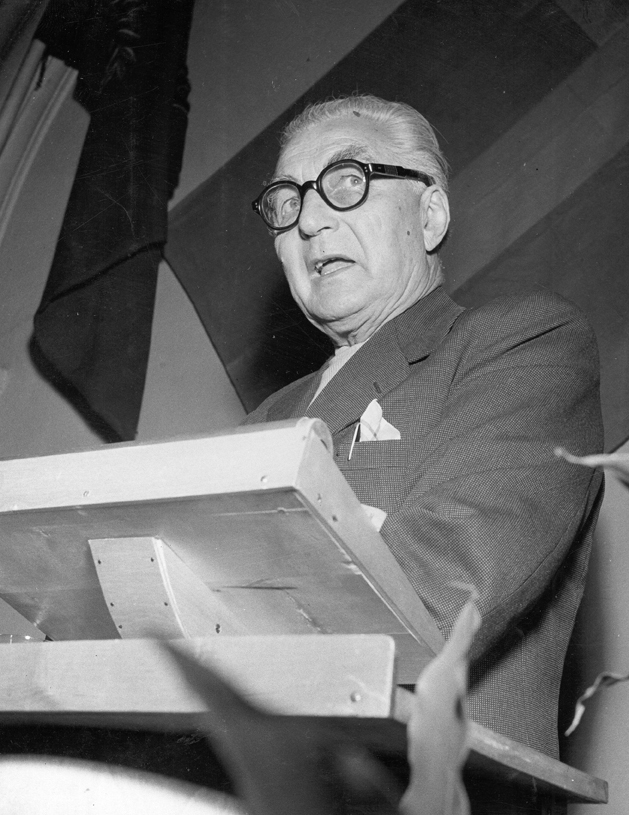

The following text was written by Karl Kilbom in 1938 after he had re-entered the Swedish Social-Democratic Party (SAP). He still remains a largely obscure figure in the history of the socialist movement, both internationally and in Sweden, but played a vital role in the development of the socialist movement in his home country.

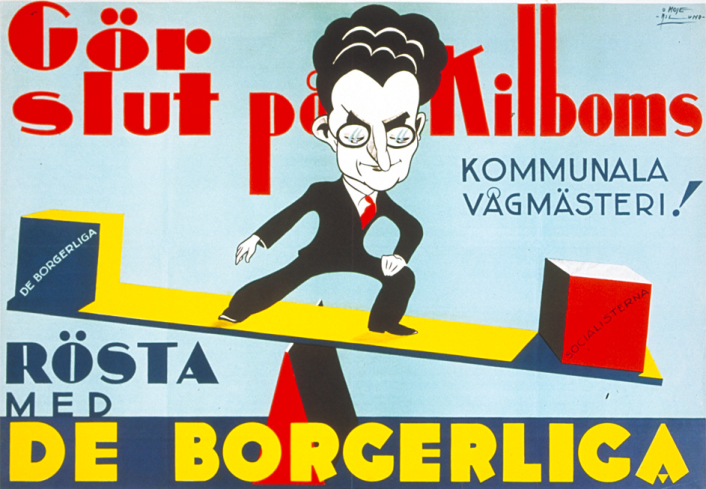

Kilbom first entered SAP in 1910. He quickly rose in the ranks, becoming secretary of the youth-wing and later chief editor of its paper Stormklockan. With the victorious February Revolution in Russia, Kilbom along with the SAP youth wing left their party to form the Swedish Left Social-Democratic party, which would later be renamed the Swedish Communist Party (SKP) as it joined the Communist International (Comintern). Again Kilbom would rise in the ranks and become one of the most influential members alongside Nils Flyg. A conflict would soon develop between the majority of the party, represented by Kilbom and Fly, and the minority, represented by Hugo Sillén. The first conflict came in 1927 during the start of the “third period”, a period of radicalization of the Comintern, when the SKP, under orders of the Comintern, started to prepare an anti-war campaign in defense of the Soviet Union. This campaign would consist of mass-demonstrations and open meetings, and to get a larger mass base SKP tried to get the syndicalist union, Central Organisation of the Workers of Sweden (SAC), to join the campaign. During talks, SAC demanded that the campaign accept certain pacifist lines or else they would break off the whole thing. Against Comintern guidelines, SKP accepted the demands, which naturally led to large reactions from Comintern-loyal members like Sillén.

The second conflict was larger and regarded the relation to Social-Democracy. Social-Democrats in Sweden still had a large party and full control of the trade unions, where they led large anti-Communist campaigns. The Comintern-loyal members accepted the theory of “social-fascism” (Social-Democracy supposedly enabling fascism, thus equivocating the two) and put forward resolutions during the 1927 congress to point out the Social-Democrats as the worst enemy of all, dedicating no energy against the right-wing parties. On the other side, it was argued that Social-Democratic workers will not be won over by trying to smear Social-Democracy. Instead, concrete demands should be put forward that spoke to the members of SAP while making them question their own leaders. Sillén thought that Social-Democratic workers can only be won over by forming or supporting the formation of a Left-Opposition within SAP, while Kilbom argued that it could only be done through concrete trade union work.

After the seventh Comintern congress, the antagonisms in the party deepened. The minority continued its struggle against the majority, accusing then chairman Nils Flyg of Social-Democratic deviations because of his support for the slogan “worker’s majority” during the general election. At this time Karl Kilbom remained vague on this point. The infighting had thus far remained inside the central commitée but started to reach members.

An issue that Karl Kilbom was more involved in was how to conduct work within the Social-Democratic trade union confederation (LO). In 1926 the party’s executive commitée had decided that a trade union conference they had arranged should act as the formation of a leftist block within the LO-unions. Kilbom was opposed to this and argued for a looser form of organizing as to avoid being purged from LO. At the time being purged from LO was a much more serious thing that could lead to being fired from a workplace if it was a workplace where the union demanded that all workers be unionized. In the end, a “unity commitée” was formed. It held a vague program and was not supposed to be directly under control of the party. In 1927 this commitée managed to do no more than some solidarity work for strikes and had involved several non-communists in essential parts of the organization. These shortcomings were mostly blamed on the organization being too loose. Kilbom remained of the opinion that a firm organization should not be formed as it would risk dividing the trade union movement. During 1928 the commitée managed to gain more ground as Social-Democrats were moving more towards class-collaboration, and the commitée managed to join the red trade union international (Profintern). LO was at the time was still connected to the Amsterdam international while the LO-union for the mining industry had joined Profintern. This, of course, sparked a strong reaction from LO-leadership, which SKP tried to repel. Nonetheless, leading communists were purged.

The downfalls intensified the struggles and the executive commitée decided that this struggle between the two factions could not be solved locally, deciding to have the Comintern’s’ executive commitée intervene. It supported the minority, which the majority rejected and started taking the line that SKP has to leave Comintern. All those who took this line were then suspended from their position and purged. This led to the formation of a new party by Kilbom and Flyg, the Socialist Party (SP). In the split, SKP was barely functioning as it had lost it’s paper and trade union apparatus. The youth-wing of SKP had to step in and replace many party functions, its paper Stormklockan acting as the party paper during some periods. During the ’30s SKP intensified their “third-period” politics by starting to focus solely on organizing against trade unions and for wildcat strikes, while SP kept its focus on legal trade union work. While this might sound as a capitulation for Social-Democracy by the SP it was still the party that led the most militant labor struggles, being the spearhead of the strikes in the paper industry during 1932, a strike that was suppressed by the Social-Democratic leadership and by force by a recently militarized police. Most crucial is SP’s struggle for a united workers’ movement. Just as Kilbom was opposed to any politics that might cause a split in the trade unions during his time in SKP, he struggled for uniting LO and SAC (which had a larger membership at the time) so that the working-class would be unified in one labor union instead of separated along labor union lines.

In 1937 Nils Flyg purged Kilbom, as Nils Flyg had moved towards being a supporter of Nazism (he saw it as the real anti-imperialist part in the coming war). Flyg died in 1943 from suicide when Nazi Germany had started to lose the war. Kilbom went back to the Social-Democrats and submitted the translated text below as his justification.

The main goal of the socialist movement for Kilbom was to struggle for the betterment of the working-class and win influence over the middle-classes and peasants. In other words to organize primarily around class interests. He saw the constant infighting in the socialist movement as the main hindrance for this, seeing these battles as a distraction from actually taking on battles for working-class victories and organizing. One should, of course, be critical of his solution to the issue of disunity, but the text is an interesting highlight of the dangers that come with splits.

The origin of the split and the reconstruction of unity

From different perspectives, the question of working-class unity in practice is being discussed in every country. The discussion has been going on for years. Naturally, the interest of this debate has been stronger or weaker in different countries during different periods. The need for unity is not as strong where the large mass of workers are part of the Social-Democratic movement. The insight of needing unity and the struggle for its realization is the most powerful in countries where reactionary forces are powerful. But the issue of splits has still not been solved here. The reasons are many. Party-maneuvers are the most prominent reason. One cannot look past the fact that the work for recreating unity is a hard and tedious process. The contractions within the working-class and its parties are not always about political issues; some specialists on party history claim that most issues are from the start personal. Different temperaments, misunderstandings about motives and intentions, not having an open heart, lacking discussions about the political situations and perspectives, but also methods and the rate of work; these are the reasons without political motives that cause struggles within the party. From this we can garner that recreating unity is not always “simply” a question of political unity. Under all conditions, a good portion of self-control is needed to heal what has been destroyed, but most of all class interests need to come first and foremost.

Under all conditions it appears as if we are in a period of unity being restored. The current situation whips the working masses into demanding it both in politics and in the trade unions. But this can not be done overnight. During the period of 1917-21 groups would split from the working masses, almost all of which have come back to Social-Democracy. With an exception for Sweden, this reunification is practically complete. In both Norway and Denmark there are small communist groups that stand to the side of the Social-Democratic movement, groups with no political or trade unionist significance. Especially in the fascist countries there is cooperation between different tendencies in the labor movement, alongside some leftist bourgeoisie groups who are also set on the liquidation of fascism. In Germany, a party of proletarian unity will come about sooner or later. In England the forces are at play to restore working-class unity; according to information, the coming general election will raise the interest of restoring unity. Noteworthy is that the secretary of the Independent Labour Party, Fenner Brockvay, explained that he was for his party being absorbed into the Labor Party. The cooperation between the workers’ parties and the leftist bourgeoisie elements in the popular fronts in France and Spain is evidence for the power in striving for unity. Of course, the popular front can not be imported into Sweden. The conditions are different here, the same goes for all other countries where the working masses have already become part of the Social-Democratic movement.

During the years before 1914, the workers’ movement marched in a united way, both in politics and in the trade unions. The largest exceptions could be found in Russia, Holland, Spain, and the USA. Naturally, there were disagreements on theoretical, tactical and political questions in the other countries as well but it was seen as self-evident that there should only be one International. The International put a lot of its work into trying to build organizational unity in the countries where workers were divided up between multiple parties.

Then came the break out of war and the collapse of the International. Especially in the neutral countries was the misery of this realized. It was not long before new attempts were made to rebuild unity, or at least get the competing groups together in cooperation. The break out of war did not just break the International, it laid the ground for prominent splits in every country, waring as well as neutral. The workers’ movement had to solve a problem that was much harder to solve than it seemed at the time. It would, therefore, be dumb to deny for example the national feelings that showed itself deep within the working-class. The youth of today have no clue of what the war actually was. Most of us who experienced its horrors have forgotten them. About 65 million were mobilized, armed to the teeth and commanded – millions thought that there was nothing else to do if they wanted to save their own and their kin, home, and valuables – to kill the men at the other side of the trench. 10 million were killed, 87 percent workers and peasants, 20 million were harmed and 7.5 million were captured. Of these hundreds of thousands would die of starvation and common disease in prison camps located hundreds of miles from their home and loved ones. And what material worths were not destroyed! Houses and factories for 50 billion were destroyed, ships for 18, and so on. In France alone about 600,000 houses were destroyed, what horror must the owners and tenants have experienced. Don’t forget that the insanity lasted four years. If all hell was loose at the fronts, it was not that much better behind the frontlines. Was it that strange the masses were finally struck by desperation? Should one not be marveled if the working-class finally, shaped for years by violence and destruction with all the inventions of mankind, would reflect on actions aligned with the formulation: “Rather an end with horror than endless horror”? After the two first years of war, the struggle to end the war was quickly transformed into demands to end the entire capitalist system with revolutionary means. Future war was to be prevented through the fall of capitalism. Even if most parts of the capitalist world has not accepted this it was at least widely accepted that the political systems that existed before the war has to be abolished. Through extended rights for the working masses bourgeois democracy was to be solidified; internationally a new judicial order was to be created for the association between peoples and a special organization to act as administrator and supervisor over this new order. Everywhere the spirit of revolt took hold. The Russian Revolution became a powerful call for revolt. The entire world listened to it. It was followed by social revolutions in Finland, Germany (the events in Berlin towards the end of 1918 and 1919 was started with sailor uprisings in Kiel and Lübeck, and was followed by revolutionary uprisings in Ruhr and Hamburg alongside Bayern and Sachsen-Türingen, in the last three locations the workers held political power for shorter or longer periods), Austria, Hungary, and Italy. There were also revolutions for national liberation in the Balkans, the Baltic countries, Poland and many more countries. That social motives also became a part of these revolutions was obvious. From August 1914 to the end of 1918 the world was at war. Already in 1917 it was clear that in Europe at least a new force of revolution was about to enter the arena. In this new situation, our part of the world remained until 1921-22. The working-masses and the anti-war bourgeoisie had a will to go on the offensive on a scale never seen before.

In this period the workers’ movement exploded. Decades of organizational work was spoiled. Naturally, we mourn this fact. Of course, the situation today would be different if workers’ unity had been kept intact. But wasn’t the split in 1917-22 then historically unavoidable? After two decades the answer can not be anything else but one. Those who broke from the old labor movement twenty years ago fully believed that through creating new parties they were benefiting the class, and all of humanity. They were ready to struggle against capitalism, the system of war and death, to the point of self-destruction. Socialism and therefore a society of world peace was to be established.

Things didn’t turn out this way! Today the situation is the complete opposite from the period of 1917-1922. Today the working-class has been pushed to be on the defensive in most of Europe. Already in 1922 it was clear that the situation was transforming into a new one – the fascists took power in Italy in October that year. At the start of 1923 Lenin got the Communist Party in Russia to radically change its course by accepting the New Economic Policy (NEP) after long struggles inside of the party. Does anyone today deny that it was necessary? Lenin explained that the main goal was to keep political power in the hands of the workers and to let capitalists gain influence on the market. For this Lenin was deemed “a tired man” who “no longer believed in the working masses”. But this retreat he pushed through preceded total or partial defeats in Finland, Germany, Hungary, and Italy. The dictatorship in the interest of the few could not be discerned. Lenin saw more clearly in 1923 than his opponents in the struggle inside the party. Today fascist or fascist related dictatorships have taken power in Portugal, Italy, Hungary, Germany, Austria, Greece, Romania, Albania, Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania. It is also on its march in South America. In over half of Europe, looking at both population size and geographical area, the democratic rights of the working-class have been fully swept away. Not even human rights are recognized. Even bourgeoisie opposition elements are faced with concentration camps. The term freedom has been destroyed. The individual is a mere number in the hands of the dictatorship. Violence, lies, and fraud between states are developing at a rate that was unthinkable even during the great war.

How did we get here? Look at Italy! A unified, organized and led working-class would, especially at the time, have considered the effects before it started the factory occupations (which was started by the leftist elements of the workers’ movement) in northern Italy 1920. This inevitable loss gave more power to the fascists. The power of a unified working-class is that it would have been able to stop this action or at least conducted a retreat in such a way that its organizations would not collapse. If the workers’ movement had not collapsed then the situation for the petit bourgeoisie would not have become as dire and they would not have joined the fascists. With the occupation of the factories in Northern Italy both the communists and syndicalists were ruined, but the workers’ movement overall took the worst hit. After the autumn in 1920, the fascist terror was regularly used against all left elements. And more importantly, the fascists retained their full support from industrialists, financialists, military, and police.

Or look at Germany. Let us assume that part of the workers’ movement’s leaders did break the revolutionary offensive through their actions. But the chain of events does not stop there. Was it not then necessary for the communists to later join forces with the national socialists, who were becoming more well-liked by the working masses? The national socialists had on multiple occasions shown their intention of liquidating the entire workers’ movement. Internal struggles had developed to such a point that the “victory” of one’s own party, or one’s own tendency, started to overshadow everything else. For these socialists, the interests of the working-class had to take a backseat if they even considered the interests of the working-class. The war between the different tendencies, which often took very concrete forms, sowed distrust among workers about the possibility of a socialist society, or to even achieve any betterments at all. This also undermined the middle-classes’ and peasants’ trust for the ability of the workers’ movement to carry out any positive politics and therefore reduced its attraction power – and so they went to the Nazis. Those who knew people in Germany before Hitler seizing power had more and more the following reasoning: “There is nothing left but the Nazis. Before we went to the Social-Democrats and Communists but now they only consist of infighting, which is why no betterment of society will come from them.” Sure, this view was short-sighted but it inevitably grew from the split. This or that tendencies can “win” during a meeting, but does not the proletarian sense for unity when the third part, the bourgeoisie, wins all when the real challenges come? The development in Italy and Germany is neither just the result of working-class disunity, it is much more complicated than that, but it could be said that the development would not have been as dire if a united working-class with the support of leftist bourgeoisie elements could challenge the reactionary forces.

We have to learn from the same experiences in Spain. Workers – and also leftist bourgeoisie elements – forces were split and at times destroyed through infighting. Would not the situation be different today if the workers’ movement started marching on a unified line back in 1931? Through its actions, even the “left” wing helped the fascists (for example the “neutrality” of the syndicalists during the uprising in Catalonia 1934 and their peer “Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification” stance during the first year of Franco’s offensive). The infighting in Catalonia, which exploded in Barcelona in May of 1937, alongside the fight between the workers’ movement in Catalonia and the workers’ movement in Spain, shows us the most horrifying consequences of splits, and the conquest of Teruel by government forces shows us again the power of unity and unified leadership gives. The development in Spain since 1936 and the grim prospect of eventual fascist victory against the working-class in countries who still have democratic states – not to speak of the risks of a new war and the developments it would cause – must be considered by the working-class. It is high time that we show that we learned something from what has happened in Europe during the last two decades. A Swedish comrade who spent six months in Spain as a volunteer in the war against fascism sent this greeting to Sweden: Do not wait with the realization of unity until you are in the trenches!

Never before during the last two decades have the struggle between the workers in our country been so limited, and contractions so small as they are now. For 99 percent there are no principal contradictions – at most one percent of the working-masses hold a diverging understanding on this question, which for now has no practical meaning. The organizational split is based on tactical, not to mention traditional and emotional, conditions. To the extent that congress decisions matter, for example, the Socialist Party have for the past few years held the same stance as the Social-Democrats on two of the most important questions: democracy and military defense. At the last congress the following programmatic statement was accepted:

“The Socialist Party urgently raise the slogan of united action to defend the working people, both rural and in cities, economic and social interests for democratic rights. Defense of democracy demands that one works to better democracy and to expand democracy in all areas of society until socialist democracy has been realized through the decision of the majority of the people.

Because of this, the Socialist Party is ready to cooperate with all groups and parties who with and through the working people build the fundamentals for politics that benefit the working-class.”

This is a far cry from wanting a dictatorship. Likewise, the party has through a string of statements from its representatives in different situations admitted the need for military defense. On more than one occasion principal declarations have been given against pacifism and “defense nihilism”.

The Socialist Party gave its full commitment to the demand for the democratization of the military, which would not have been possible if it had been on principle against defense.

Considering all the circumstances, the development of the Social-Democratic party’s politics has proven to benefit the wide layers of people, who on a larger scale give their support back (last election the party got about 300,000 more votes). Therefore there is no reason from a worker’s perspective to not give them active political support. Each one who dreams of real politics must from now on admit that for the foreseeable future workers only flock around the Social-Democratic party. This can not be done with the old Socialist Party or the Communist Party. Even less would they be able to cooperate with the peasants and middle-classes. Under the current conditions in the world, it would be dumb, a crime, to refuse the support from the groups of people, both for what has been won and the coming politics, which with all its force aim to better the lives of those who have it the worst.