Volodymyr Chemerys is a well-known political activist with left-wing, pacifist views. Born in the Sumska region of Ukraine, Chemerys, whose native language is Ukrainian, was removed from the Komsomol and his university position in 1982 for “anti-Soviet activity.” In the 1980s, he would play an active role in the Ukrainian nationalist movement. His prominence in famous protest movements like the 1990 “Granite Revolution” led to various problems with the Soviet government. However, after the fall of the USSR, Chemerys’s political views became more left-wing. He was always consistent in his support for democratic rights, playing a leading role in the 2000-1 protests against Leonid Kuchma’s authoritarian, pro-business government, as well as other protests in Ukraine throughout the 21st century. Because of his left-wing activism (as well as that of other left-wing parties strong in Ukraine at the time, including the Communist and Social Democratic parties), the Ukrainian constitution was edited in the 2000s in order to guarantee more social rights.

Chemerys has constantly railed against constant violations of this relatively progressive constitution. His defense of political pluralism and socio-economic rights led him to become one of the few remaining critics of the post-2014, “Euromaidan” order in Ukraine. His public stance against war and violent wartime repression led to his persecution by the Ukrainian secret services in 2022. During interrogations where the secret services were accompanied by masked, right-wing paramilitarists, Chemerys had his ribs broken by the latter. The NGO “Chesno,” a liberal-nationalist group funded by the NED and various NATO countries, has a large dossier on Chemerys online, accusing him of “left-wing propaganda” and of supporting the Minsk peace agreements. This website, similar to the infamous “Mirotvorets,” doxxes personal information of what it calls “traitors.”

Interview and translation by Alex Andreev.

Civil Rights and Their Defense

Why did the government ban Ukrainian TV channels such as ZIK, NewsOne and 112, as well as independent online publications like Strana.ua in 2021?

The channels were banned in a way that contradicts the constitution—even today according to Ukrainian law it is only possible to close a mass media platform by decision of a court, not by presidential decree. They were banned because these channels showed various points of view. The TV channels gave a platform to both government perspectives and, most importantly, left-wing points of view, alternative points of view. I saw how many people were angered by their closure. People find it more interesting to view a variety of perspectives rather than simply one.

And after several months, when people all watched either pro-government channels, or Poroshenko’s channels—which present essentially the same views—people changed. First, the channels went on Youtube, but then they were banned there too. And then only one option remained for alternative points of view— Telegram channels. But only a small proportion of Ukrainians read them. People mainly watch official propaganda.1

Do you have any examples of how people have changed?

There are lots of examples. But you need to consider another factor—many people are simply scared to say what they think. There are many, very many such people. One Ukrainian sociologist said that lots of social polls are conducted, but this is absolutely meaningless. If you go up to any person and ask him what he thinks, then 90% of people will answer that they love the government and hate Russians.

Why did attempts to try Poroshenko after Zelenskyy came to power in 2019 fail?

Not only after Zelenskyy came to power. For instance the murderers of the journalist Oles Buzina in 2015. They were essentially proven guilty. But they have walked around as free men for 6 years. The court process drags on forever. And the murderers of the Belarussian liberal journalist Pavlo Sheremet in 2016. Or the murderers responsible for the deaths in Odesa on the 2nd of May, 2014. Not one “radical” nationalist has been punished. Why? Because these right-wing Nazis have become part of the state apparatus and official Ukrainian ideology. It is possible to speak of total immunity for these people.

How did Ukrainian human rights defenders react to the wave of political violence in Ukraine after 2014?

Nowadays in Ukraine, not only has journalism died, since we have a single news channel controlled directly by the government, but human rights activism has also died. An example of this is the debacle around Amnesty International’s August 2022 report. They had the courage to speak up about how the Ukrainian armed forces are using human shields. And the Ukrainian branch of Amnesty International condemned Amnesty International Central.

The Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group never had any statements about the closure of television channels. But they did protect Serhii Sternenko, a right-wing murderer. They tried to show that the murder was actually committed in the name of self-defense. Nowadays, they are busy repeating Liudmila Denisova’s statements, who was sacked from her position in the Ukrainian government as human rights ombudsman for repeated unproven statements about the rape of Ukrainian children by Russian soldiers. But this topic of rapes remains one of the favorite topics for so-called Ukrainian human rights defenders, as well as proving that any trial of Azov soldiers by Russia is illegal. Nothing about repressions. Only the Telegram channel “Repression of the Left in Ukraine” talked about this. In Ukraine, it has long been common practice to call so-called “human rights defenders” “ultra-right defenders,” since they only defend ultra-right-wingers.

Can you give me some examples of the difficulties that human rights defenders encountered in post-2014 Ukraine?

People must have the right to defense in a court of law. There are many examples of unjust imprisonments for political motives in post-2014 Ukraine— Ruslan Kotsaba, defended by the Ukrainian lawyer Tetiana Montian, spent 1.5 years in jail for a video he shared in 2015, calling not to fight in the war, for which he was accused of “not allowing the army to function.” Vasily Muravitsky, who spent a year in jail for “state treason” in 2018 after he wrote articles exposing mafia links to the state in a central Ukrainian province, found sanctuary in Finland at the start of this year as a political refugee. Dmitry Vasilets spent two years and three months in prison for trying to create a Youtube channel. Not one of these people have been pardoned by the state. The court processes continue. The London office of Amnesty International officially considers Muravitsky and Kotsaba prisoners of conscience. The fact that they were released is a victory, though of course it wasn’t the “ultraright defenders” I mentioned earlier who defended them— if they had, they would still be in prison.

What have the consequences of “decommunization” been for political life?

Because of this law, people receive real prison sentences for citing Lenin and Marx on social media. Existing left-wing parties have been totally liquidated— they cannot use their symbols, they cannot participate in elections, and so on. On the television we have constant anti-Communism, Banderist ideology is pushed into everyone’s heads. It has become the official ideology. It’s no longer possible to speak of any legal left-wing political activity. I think that the absolute majority of people in Ukraine have no real anti-Communist convictions, but because of the political atmosphere they don’t dare to say otherwise.

Did any human rights defenders try to challenge the decommunization decision?

Yes. Of course, in 2015 the situation was such that they wanted to ban the Communist Party, but the court of the first instance stopped them from doing so. But this decision did not enter into effect because there was an appeal. Then it went into the constitutional court, and that’s when international lawyers entered the fray, including one left-wing English lawyer, whom I know. Until 2022, the Communist Party was not formally banned. But the Communist Party was banned from taking part in elections. Not by court decision, but by decree of the Ministry of Justice which, on the 23rd of July 2015, clarified the laws about decommunization, their legal meaning. The ministry explained that the Communist Party no longer had the possibility to conduct any actions. In 2022, the procedure for banning political parties was simplified, and the Lviv Court began quickly banning left-wing parties. They banned all the left-wing parties.

Nazi symbolism is also formally banned by this legislature, but no one ever pays attention. It is very easy to freely use Nazi symbolism, and the courts are not interested in this.

How did grant-fed NGOs influence Ukrainian political life?

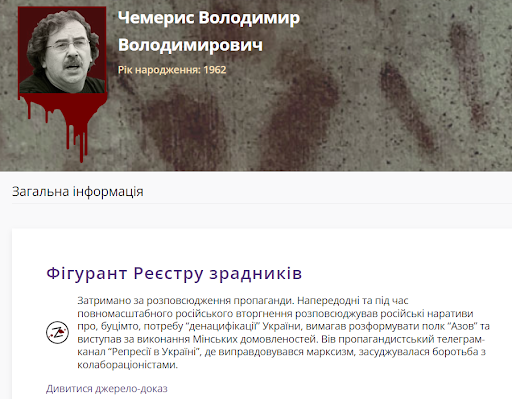

They have influenced it quite strongly. This is done through press censorship and because mass media is significantly financed by various western funds, which means that alternative points of view have no chance. In turn, control over information sources influences political life. Recently the USAID-funded NGO “Chesno,” or “Honestly,” created a list of “state traitors of Ukraine” including myself, with detailed information about my personal life. The icon for my page is a photo of my face, dripping in blood. I am there because I “find excuses for Marxism.” The government likes to create such lists of traitors. This is also a means of influencing political life.2

Why did it happen that after Maidan, political forces came to power who claimed that “freedom is our religion,” but the level of political violence and intolerance increased?

Because in the modern world it is, of course, not acceptable to say that slavery is our religion. But in the modern world it has become very popular, as Orwell once wrote, for freedom to be slavery. They took what he meant as a warning as an order.

The West and the Ukrainian Ruling Class

What is at stake in the struggle between Zelenskyy and Ukrainian oligarchs, given that the former often speaks of “deoligarchization,” even creating a law dedicated to this struggle?

There is no struggle against oligarchs. They have absolute power. The reason for their existence is not in any laws, but in the socio-economic situation. In fact, all these reforms— in medicine, in labor relations, and so on— all of them were made in the interests of big capital linked to the state. The law on oligarchs was created in the interests of imitating this struggle. To show this to the USA, given that the latter wants to have total control. But for the oligarchs, this law means nothing. The second aspect of this law is that Zelenskyy wanted oligarchs to be controllable. Like it is in Russia, although they have no law for this. But he didn’t want to destroy them, just to control them.

Why have there been so many conflicts between Zelenskyy and the Ukrainian constitutional court?

The objective here is putting the court system and institutions that have a monopoly of violence under the control of the president. This was a hallmark of the presidency of Viktor Yanukovych, but existed even under President Viktor Yuschenko. But a new player appeared—Washington— which wanted to control this system. That’s why all these different “observer councils” with foreigners were created. The office of the president resisted because it wanted to control the courts itself.

Why did Zelenskyy sanction citizens of Ukraine in 2021 and early 2022, and to what extent did this obey the Ukrainian constitution?

I was among those who wrote the first article of the constitution— it stipulated an independent, democratic, social government. None of these are true today. We have at least 10 news agencies that are banned— not banned by any courts, but by presidential decree. We have 15 political parties that are banned, all of which are left-wing. First that was done by presidential decree, and then the laws regarding the banning of parties were changed. Our constitution is today a revolutionary document— it contains social rights, political rights. Zelenskyy ought to ban this document.

Has the struggle against corruption brought about any real successes, and why is it being waged?

Any government struggles with corruption. It is what is expected. On the other side, it is necessary to understand that if a person is integrated into the upper levels of government he can calmly engage in corruption. The government over the past year or so liked to talk a lot about the “Big Build” project and there was lots of corruption there. But in that case the corruption was organized by the office of the president. Also, of course, there is corruption which is not linked with the upper levels of the government.

But the “struggle against corruption” here is always simply a struggle against those corrupt figures that don’t have a criminal racket to protect them. For instance, the “struggle against the corrupt” members of the pre-2014, pre-Euromaidan government. But the new corruption feels totally at ease. At the end of the day, the US State Department demands the struggle against corruption, so the government acts as if they are doing it.

Why does the US State Department demand it?

Because they send such large amounts of aid, and there are plenty of instances of corruption in the use of this aid.

How strong is the influence of foreign agents in “reformed” state institutions, like the court systems, Ukroboronprom, or Ukrzaliznytsia, and in the selection of state officials?

The presence of foreign agents is their determining function, as they form the majority in these various “supervisory committees.” For instance, the West constantly pushes on Ukraine to continue allowing the existence of a 6-person board which screens potential Ukrainian judges— three of those on this board are foreigners. The aim of the people in such supervisory organs is not to manage these organizations properly, but to choose people who protect the interests of transnational capital.

Sometimes Kyiv has some spats over this topic— for instance in 2021, when Yuriy Vitrenko came to replace Andriy Kobolyev in the management of the state energy company NAFTOGAZ. Kobolyev was a Western favorite, so the USA and the EU replied to this move with a hail of criticism on the move of the Ukrainian government to dare to put someone in charge who “isn’t our guy.” After that Kyiv didn’t dare not listen.

Political Activism, Change, and History

Which domestic social groups are interested in maintaining the status-quo in Ukraine— economic dependency and degradation?

It is necessary to separate those who want to join the West from those whose social interests are socio-economically dependent on the West. The propaganda which is today absolute in Ukraine— we have one TV channel controlled by the state— says only one thing, that everyone wants to be part of the West.

Perhaps the majority of Ukrainians think that they are for the preservation of the status-quo, but actually, those who are objectively interested in the preservation of the status quo are principally a powerful class of compradors and a middle class which ties its well-being with import-export operations, and wants to live “like they do in Europe.” In fact, of course, these are not the interests of, in the first place, workers, since dependence on the West means, first of all, deindustrialization. That’s because Ukrainian industry is mainly tied to Asian, African and post-Soviet markets. But the EU is uninterested. The root interests of the working class therefore consist in wanting to change this situation of dependency on the West.

What is the Ukrainian “middle class?”

The middle class in Ukraine, if we are talking about people who have a medium level income, includes various social groups. It also means highly qualified workers and sailors. If we look at the numerical size of this class relative to Ukraine’s total population, it’s not a very big group of people. But the thing is that small shopkeepers compose a very large share of Ukrainians although their incomes are often so low that it is difficult to consider them part of the middle class. But since they are property-owners, they are interested in the preservation of private property.

How can the Opposition Party For Life (OPFL) party, which was led by the now-imprisoned Viktor Medvedchuk, be characterized? What is its relation to the Ukrainian working class?

The OPFL is a party that represents capital, but it is a party that represents national capital. The latter is interested in developing Ukrainian industry based on Russian and Asian markets. This is where they overlap with the interests of the Ukrainian working class, who also want to have jobs. Of course, there are still class contradictions between the two. But this is why the OPFL always got the most votes in the industrial regions of the southern and eastern regions of Ukraine.

But it is necessary to begin from at least 2014, when all organizations representing the national bourgeois and the working class, ceased to be able to function. A totalitarian government then appeared. Workers and all other social classes were pushed to believe that they have a common enemy. In such a situation there was no possibility of any resistance.

There are no real oppositional organizations. Everything is immediately attacked. 40 thousand people have been arrested since the 24th of February 2022, including left-wing activists in regional cities. They are sitting in prisons. The model that has been pushed in Ukraine since 2014, where all free thought is crushed, where militarism is systematically pushed on everyone, can exist for a certain time with foreign assistance, but sooner or later it has to collapse. Then, the left-wing can organize itself and I am sure that it will be able to present a left-wing idea for Ukraine’s development.

On what questions did Ukrainian Leftists split after 2014?

There were no matters of principle as far as I can see. There were some small Trotskyist groups, and some more orthodox Leninists like Borotba. They even united in the “Union of Marxists” but this quickly fell apart. But I don’t see any reason why they had to split—these reasons were left behind in the 1930s. It’s just as irrelevant as the split between the Ukrainian nationalist Banderists and Melnykists.

The reason for the split was just personal ambition. This was the reason why this new Left couldn’t be supported by any broad movement, or by the working class. The Communist and Socialist Parties had such a wide base, but they were in the Ukrainian government in the years before 2014 and weren’t able to show the masses why it could be worthwhile supporting them. When there is no support for a wide movement, personal interests dominate.

After 2014, a split emerged between the people who said that there is no Nazism in Ukraine and that it was necessary to send Ukraine weapons, and those who disagreed. The first group forgot that thousands of their comrades sit in Ukrainian prisons, and that it is they who want to change the situation in Ukraine. I think that those who became the weapons of the radical, right-wing regime have no political future. Either the government will collapse, or they will become the government’s next target. This government always needs an enemy to justify its existence, to destroy the civil rights of Ukrainians.

What strength and functions did right-wing groups have before and after 2014?

Their strength wasn’t electoral, since radical right-wing groups only received 1-2% in elections. They have no support in Ukrainian society. But they are essentially in power in Ukraine. They have the right to use violence in the country, and that is what state power is all about. The ruling class needs such stormtroopers to protect it, to destroy its enemies. Arendt wrote that totalitarianism needs a totalitarian movement. That’s what control is. The state apparatus by itself can’t control all of society. This is why you have such brownshirts. They are directly financed by the state budget, they are given weapons. “Municipal Security,” a para-police organization run by open neo-Nazis, is financed by the Kyiv city budget, the Azov Battalion is financed by the Ministry of Internal Affairs; NGOs and the Ministry of Internal Affairs finance right-wing children’s camps.

How strong is the idealization of the West among Ukrainian political figures and the general population?

Before, such feelings were more widespread among the population—when the USSR fell apart, everyone went to McDonalds. In the USSR, the idea that in the West, everyone lives wonderfully, was very widespread. This worked wonderfully in the last Maidan, when Euromaidan leader and Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk said that if you want a pension of 3000 Euros, then you must support entering the EU.

This opinion still exists in Ukrainian society but already much less than in the 90s, since many people have already gone and seen how people live over there. These views are very popular among the elites, both Ukrainian and Russian. They want to live in the West, to buy mansions and yachts there. It is considered more prestigious.

What kind of Ukraine did you hope would emerge when you were a political dissident in the Soviet period?

Not what it is now. Now in Ukraine, we have the worst aspects of the USSR, but much worse. In 1983, I was arrested by the KGB for nationalistic activity. But if I compare my experience with them with what takes place now, then the KGB agents were cultured people with white gloves. I always had left-wing views and I hoped to see a socially just, independent Ukraine. Freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and so on. What we have seen for the past 8 years is the total repression of civil rights. This has led to the disintegration of Ukraine— this model is unsustainable.

Why did you participate in the “Granite Revolution” of 1991, and in the protests against president Leonid Kuchma in 2003?

I wrote two articles in the journal “Day” in 2003 regarding the anti-Kuchma protests. I wrote about how an oligarchic capitalism had developed in Ukraine, how big capital had taken state power, crushing any social or democratic organization. I predicted a social explosion, which indeed happened. I personally knew Gongadze, the journalist whose death sparked the protests. People wanted to change their lives.

For me, it was a protest against something, a negative protest. It managed to remove Kuchma, but that wasn’t what was most important. What was most important was that it was the first time that it was stated in Ukraine that it was necessary to “change the system.” According to polls conducted afterwards, those who supported the dictatorship before the protests changed their minds, they became antagonistic towards it.

What was your position regarding the Euromaidan events of 2013-14?

When “Ukraine without Kuchma” finished, it was because there were violent clashes. But the social contradictions didn’t go away. Sooner or later, they had to explode again. Big/comprador capital stood against practically all other groups—workers, pensioners, the intelligentsia, small business. This was fairly early on—2004. This contradiction had to be resolved.

However, a new government had to emerge which could have represented these groups. In 2014, the government changed, but only nominally. Only from one fraction of big capital to another. We had a campaign to vote against all the candidates— “Shameful to Vote.” I made a speech in 2014 at Euromaidan. There were various left-wing groups there, but there was no unified left force. When I spoke there and delivered my program, all forces at the Maidan supported it. But in that situation, a different faction of big capital took power. In addition, there were many ultra-right forces in 2014, which committed a great deal of violence, thereby starting a civil war.

Why were left-wing organizations so weakly represented in Euromaidan?

During “Ukraine without Kuchma,” many left-wing parties were active and dictated the agenda of the protests. In 2014, different forces dictated a different agenda. There were attacks on left-wing activists such as Denis Levin. There was no left-wing political force present at this time.

The Ukrainian Communist Party and Socialist Party were once among the governing parties in Ukraine, all the way until 2014. But in their time as governing figures, they did not push through any progressive social reforms. Because of this, their influence fell. Their influence on trade unions fell.

One important moment was also that a part of those who called themselves left-wing showed themselves to be the avant-garde of the ruling class, and even of Fascist forces. In the repressions against the Left going on today, some of those who tell the secret services to repress them are themselves “left-wingers.” Sometimes they even do it directly on social media, on public Facebook posts. Sooner or later, a clarification of what constitutes the left-wing movement in Ukraine will take place, since now all left-wing organizations are banned, but when they aren’t, then there will be a new development of left-wing forces.

In all these different protests, alongside various social struggles, national sovereignty was often put forward as a key demand. What importance did and does national sovereignty have for you?

The question of sovereignty was important for me. For me, independence, democracy, and a social government are what is most important. Ukraine’s non-aligned status was written into its declaration of independence. Ukraine’s location dictates the necessity of such a non-aligned status. It was precisely whenever Ukraine went in the direction of one bloc or another that problems started arising. We should become not a wall, but a bridge between the West and the East.

Non-aligned status is the key to sovereignty. When people say that they are upholding the independence of Ukraine today, they are doing nothing. The USA simply commands which ministers to choose, which laws cannot be accepted. For instance, the US forbade Ukraine from accepting a law proposed in 2020 about industrial localization. All other countries adopted laws supporting local business during the Covid pandemic, but the US shut down Ukraine’s attempt at doing so. This has led to the deindustrialization of Ukraine. There is also total control over all the army, the police, the courts. Before the war, Ukraine adopted laws regarding the privatization of agricultural land, allowing foreign entities to buy land as well.

What demands do you think that progressive, left-wing forces should unite under in Ukraine?

- Independence above all. Ukraine has ceased to exist as an independent state.

- Democracy. This is directly linked with liquidation of ultra-right-wing forces.

- Socialism.

What social basis exists for such a platform?

We have already seen, since the early 2000s, that the principal contradiction in Ukraine is that between big capital and everyone else, from workers to pensioners. This contradiction continues to exist today, even if it isn’t always so visible.

Is there any continuity between the political processes which took place beginning in 2014, and those which took place throughout the post-Soviet period in Ukraine?

I once read that any changes, any evolution pushes society towards a less repressive state. Marcuse wrote about that. But I have seen that this is not always true. Revolutions and change can make a society which is more repressive. It is not objective factors, but subjective ones which decide— who takes advantage of the fruits of the revolution.

When I think back to “Ukraine without Kuchma,” and the student movement in the late 1980s and early 1990s, what happened isn’t what I wanted. It is this which is the tragedy of my generation. The tragedy is that this was in a sense a predetermined process— we had different aims, but it ended up very badly.

At the start of the 90s, the aims that people put forward resulted in the opposite of what they wanted. It isn’t nice to feel that you somehow took part in this, hoping that it would lead to positive changes. But it led to absolutely different results. The best example of this is the Baltics and Georgia. In Georgia, all these demands put forth in the 2003 “Rose Revolution” for democracy and social change transformed into a dictatorship. But Georgia managed to get rid of it. And we will also manage to do so.

What aims were betrayed?

Independence, social justice and democracy.

- Editor’s note – this interview was conducted in 2022, but in 2024, more and more Ukrainians prefer to get news from Telegram rather than from the government-controlled TV channels.