Roland Crisafulli argues against partyist mentalities within the DSA and offers an alternative strategic outlook.

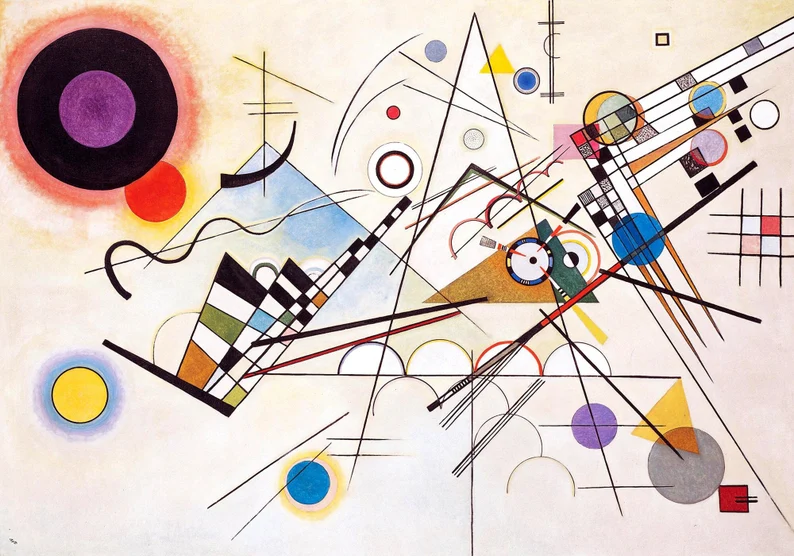

Wassily Kandinsky, Composition 8 (1923)

We are coming up on the 20th anniversary of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. It has become customary for leftists to refer to this particular crisis as an objective condition for a renewed interest in socialist politics. Since that time, many organizations outside the DSA have fallen considerably in prominence and ability to carry out political work.

There is some irony to the recent marked decline in Leninist organizations in the US. After all, mass engagement in left-wing politics has not suffered a concurrent fate. Interest and engagement in trade unions has certainly increased among the younger generations, while interest in Palestinian struggle has gone from a fringe radical issue into a cause that mobilizes thousands and even millions within the US, Israel’s strongest ally.

Still, without a political vision and leadership, an abstract popular grasp of the flaws of the system cannot result in an ability to confront the state as a whole, the objective conditions as a whole. The people’s rage can subside and fail to create an unbreakable political subjectivity as strong as the state. There is a disconnect between passing popular rage and ivory tower Marxist commentary throughout the ebbs and flows of popular resistance. This frustrating cycle takes place in the shadow of an increasingly fascist-leaning status quo that ought to provoke more organizationally and politically serious responses.

The DSA, for its part, has continued to develop and even to grow throughout this period. But while the DSA is not as socially and politically isolated as many self-styled “vanguard” organizations, it too frequently finds itself on its back foot with regard to many positive mass developments. The DSA comments prolifically, and signs up large numbers of members, but it is difficult to argue that the DSA plays a “leading” role in political work on the whole. The DSA represents a place where the more serious left meets, and common positions emerge therefrom. But this does not allow people outside of the DSA to grasp a coherent vision for moving from capitalism to socialism, or to pursue concrete decolonization or anti-imperialism. For those within the DSA, visions for the above are (perhaps unavoidably) varied.

Obviously it is better to have a practical meeting of leftists interested in actual politics than a farcical “leadership” of a fantasy vanguard politics. In fact, we can say that no real vanguard (and certainly no vanguard party) exists for the socialist Left in the US at this time. But the DSA itself, despite having many members who disdain the concept of a “vanguard,” does not lack discussions of how to “lead” the movement forward. There are even a good number of DSA members, (and their number appears to be growing), who openly speak of the need for a “vanguard,” although they (rightly) disdain the culture and methods of those groups which already exist claiming to be “vanguard parties.” In a sense, even if the DSA as a whole has no official commitment to “the vanguard party,” the DSA will increasingly confront the same problem of how to be a vanguard, which so many Marxists have faced in the past.

Why do so-called “Vanguards” fail to play an “Advanced Guard” role?

“Vanguard” organizations in the United States have a rather poor reputation – both for their internal political culture and their actual efficacy. Critiques of specific organizations and policies are dime-a-dozen, so I will limit myself to critiquing the most common delusion and how it fails to conform to reality in almost any country.

Ostensible US “vanguards” tend to labor under the delusion that their current model of politics, if pursued vigorously and for long enough, will eventually break through the backwards thinking of the majority and rally the entire working class of the United States behind their self-evidently glorious and great leadership. The problem is that there is no “rallying the entire working class” behind any one of the political organizations of the radical left which exist in the United States under present conditions, for reasons that have very little to do with how good or bad these organizations might be.

The model of vanguardism which these organizations are pursuing is effectively the model of the Comintern era. The Comintern came into being 100 years ago, right after the October Revolution, and just before the various substantial splits in the communist movement and the rise of fascism.

The Comintern and the CPUSA of the day had a number of advantages that the international communist movement of today lacks, not least of which of course is the existence of the Soviet Union. These allowed for relative ease of recruitment and organizing that any aspiring vanguard group in the US today lacks:

Firstly, in the early 20th century, both within any given country, and across the world, the proletariat as an objective economic class was smaller than it is today. Regardless how much or how little focus a given party puts on direct worker organizing, this means it is much harder for it to achieve dominance of the whole class than it would have doing the same work a century prior.

Secondly, the state was a smaller and less advanced machine 100 years ago than it is today. Information technology, weapons technology, experience in suppressing revolts, expertise in infiltration and harassment – all of these are more substantial tools for the state than they were a century prior.

In addition, the imperialist world system has allowed for more kinds of division between the proletariat in objective terms: border regimes, biopolitics, culture wars, the gig economy, etc. The task of organizing “the entire working class” on a national or international level is much more daunting today, in part because each worker experiences their exploitation and oppression differently, in both ideological and practical terms.

We are faced with the fact of a disproportionate proletarianization of the oppressed nations, with poverty rates and job insecurity being much higher than for the dominant nations of the imperial core. The political needs of oppressed groups are marginalized from the agenda of many workers and worker organizations of the imperial core nationalities, which in turn leads to disunity of workers, as each must look after their own interests.

Taken as a whole, we begin to see a picture of truly divided masses of working people; one that calls for a requisitely large amount of organizing work to unite behind a meaningful political leadership.

The task of uniting in political leadership is a practical one; it requires actual work. It is not declared, decreed, or declaimed, to be accepted by passive hordes of hungry and oppressed poor. This leads us to the importance of working within a popular front of progressive forces and a united front of socialist forces.

It is sectarian to act as if one already is the recognized vanguard without having proven oneself to some extent before the broad masses. This would be true at any point in history. But objective conditions at present, in particular in the US, require coalition: if we have any faith that building a strong left is possible, but also harbor no delusions that such a strong left already exists and is objectified in our special vanguard grouplet alone, we must maximize our impact by standing together with those doing the same sort of work on the same fronts.

That those we will work with seamlessly on one issue will disagree with us strongly on another is expected: otherwise real organizational unity would be an obvious act, almost a mere formality. To reach that unity in reality, however, we must confront, discuss, and debate positions and styles of work where we disagree, with those groups with whom we have already established trust and respect through common work on which we agree.

In fact, even in Russia in the early 20th century, relations between the Bolsheviks and their former allies – anarchists, Left Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs), Mensheviks, even certain strands of liberals – became wholly untenable only after the October Revolution, and not before it. In a country with a much larger and more divided proletariat, the error is not in trying to emulate the Bolshevik party model, but in acting like the leaders of a party-state when most observers would scoff at calling our organizations political parties to begin with.

However, as I mentioned in the introduction, most groups with this sort of delusion are in a current state of rapid decline. Instead, we are faced with a problem of overcorrection: rather than a proliferation of would-be vanguard cults, we see a liquidationist trend, a timidity about one’s own political subjectivity. Large sections of the DSA fear “alienating voters” by disagreeing with the Democrats about clear points of principle, union organizers shrink back from political education, and student radicals feel satisfied with classroom-constrained critique.

Often even the self-declared “vanguard” organizations tail the cause du jour, inserting their members as staffers of unions or NGOs, and resting on the laurels of this “success.” From protests to elections to union organizing, most of the US Left very well understands the importance of popular or united front tactics and coalition building. They understand it so well, and are so afraid of sectarianism, that they do not present a subjective leadership with a plan for a different path forward. They act as anti-vanguards – “Marxist” “rear guards” of US socialism.

Building a Vanguard Organization Within the DSA?

Can the DSA fix this problem? In short, no. Barring significant leaps in consensus around not only the analysis of the current state of the US, but of what we seek to replace this state of affairs with and how, there is no reason to expect that the DSA can simply become the vanguard, whether it uses that word for itself or not.

Rather, we should view the DSA as an inevitable practical structure in the face of a still-developing, highly divided Left. Whether they are DSA members or not, socialists in the US who are concerned with practical work and not mere armchair commentary find themselves “in the trenches” with the DSA, time and time again. In fact, this is the main reason so many join: the DSA is present on so many fronts of left politics, and yet the ideological barriers to membership are low enough to include more-or-less everyone. What can be called the DSA’s weakness as a leading thing is its strength as a meeting place.

More to the point, the DSA “caucus” system allows for socialization and problem-solving on a collective level greater than the individual and their friends, but smaller than the whole DSA. The challenge that we face, one that the DSA’s existence and existing structures do not automatically solve for us, is how to overcome the trend towards inertia and liquidationism within and of the DSA itself. In other words: once you are in the DSA, and once you have developed views on where we should be collectively going, where do you go from there – so that you’re not simply sitting in your corner, feeling more clever than everyone else?

Some individuals and caucuses seem to believe their goal ought to be the ideological takeover of the DSA by their clique, or the creation of a coherent political party out of the DSA. This is a mistake. If the DSA can be conceived of as a political party, it is a party of the same kind as the Republican or Democratic parties – it is a “big tent” with very broad values. Most of those who speak of the creation of a party from the DSA or position their own future leadership of the DSA as the goal have in their mind the idea that the DSA would take stronger and more unified positions on even more issues than it does today. Naturally, these stronger and more unified positions would be their own positions – positions which, if stated vigorously and for long enough, will eventually break through the backwards thinking of the other caucuses and rally the entire DSA behind their self-evidently glorious and great leadership.

This is obviously putting the cart before the horse: the reason why so much of the DSA can disagree so strongly on such crucial questions as fascism or imperialism and how to confront them, is not because they don’t already have a charismatic enough leader at the head of the DSA. It is because neither the DSA as a whole nor any faction therein are prepared to lead even microcosmic practical struggle to an extent that would win converts over to their positions, should they be proven correct.

The DSA is at present and will remain for the foreseeable future, with whatever flaws and merits, an honest formulation of a united front for the US socialist Left in practice. What the DSA (and by implication the socialist Left in the USnited States) ought to look like, what positions it ought to take, and how it ought to act, can and will continue to be debated.

But to advance the goals of greater coherence and political leadership, it is not sufficient to write more texts arguing for this or that position: it is necessary to combine broad united work with semi-independent work of the like-minded on the more contentious positions. A caucus, a clique, a pre-party formation, whatever the formulation, exists because it believes in its own unique insight. There is nothing wrong with that. For such a group to project influence outward, both within the DSA and to the US socialist Left more broadly, it must carry out work that demonstrates this insight as leadership.

Obviously there isn’t a perfect formula for when and how much to engage in polemics across the DSA or struggle for hegemony over the DSA on every single issue. But when there is disagreement, there is a tendency to either dig in one’s heels over trying to “defeat” one’s DSA rivals, or alternatively to simply abandon DSA altogether. Both can be mistakes: if one feels that the local DSA is engaged too much with DSA-internal politics and not enough with worker or tenant organizing, it makes sense to shift focus to doing that work yourself. But rather than pretending to have outgrown the DSA, one can use such work to build and develop an organization that operates within the DSA as well as beyond the DSA.

Running candidates and popular campaigns, organizing a workplace, etc. when you are one step ahead of the DSA as a whole can be both an opportunity to gain confidence in a more defined group and line than something as broad as the DSA can universally provide, and also a means to demonstrate to others within the DSA the distinctive value of your group as a force that means something both to the working class and to the DSA.

This is the difference between political theory and practical politics. By boldly staking claim to your politics within and beyond the DSA, by signing your name to something that matters off the pages of your journal, while also developing your theoretical line in conjunction with this real work, you make clear to others why you matter. When they are paying attention to you, individuals will be more inclined to follow you, and the more like-minded organizational structures will debate the points which obstruct unity. By contrast, if nobody on the outside is paying attention to you, the forum in which you speak becomes smaller until it becomes a dreaded echo chamber.

Being in the DSA should not mean jettisoning the idea of confidence in one’s politics and leadership in favor of an assumed strength in numbers that the DSA provides. But the remedy for this liquidationist trend is not to simply start treating the DSA as a bigger replacement for the manifold attempts at socialist parties within the US. By being realistic about one’s own limitations to act independent of coalitions of the broadly like-minded, as well as the coalition’s limitations to act as a “full” reflection of one’s own politics, one can build and lead in practical terms, evade sectarianism and liquidationism, and begin to form a meaningful vanguard politics for socialism within the US.