Matthew Strupp examines economic debates in China during the leadup to the Great Leap Forward and assesses comparisons made between Mao and Bukharin. Reading: Cliff Connolly.

A common understanding of the political history of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is that it underwent a grand “two-line struggle” in the years from the completion of “socialist transformation” with the nationalization of industry in 1956 up to Mao’s death in 1976. The two sides between which this supposed struggle took place were the Liuists, or capitalist-roaders, and the Maoists, the genuine Marxist-Leninists. This view is still common among Marxist-Leninist-Maoists, and until Liu’s rehabilitation under Deng1 this was the official verdict of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) on its own history. It was replaced by a view that attributed to Mao the great merit of having revolutionarily unified the country but no longer asserted the correctness of his line in these struggles, no doubt since his line, posed against capitalist-roaders, had uncomfortable implications for the new leadership.

The problem with the original “two-line struggle model” is that it washes away much of the complexity of the actual politics and virtually ignores the competing bureaucratic interests involved in the decision-making process of the Chinese state, though this is also true of the view that replaced it and in questioning the one the author by no means intends to endorse the other. The effect is to thoroughly reduce the economics and politics of this attempt at socialist construction to a caricature, replacing political and historical analysis with a confession of faith.

An interesting alternative framing to these ways of understanding the politics of the PRC is the approach of R. Kalain. In a 1984 paper, Kalain argued that Mao had a distinct “Bukharinist” phase in the late 1950s, coming to similar politics as the Bolshevik revolutionary, statesman, and economist Nikolai Bukharin despite a lack of a direct influence from him. Bukharin is known for advocating for the continuation of a modified version of the New Economic Policy. He opposed the early ’20s “super-industrializers”, as well as the late ’20s forced collectivization of the peasantry and the first Five-Year Plan.2 Kalain argues that Mao criticized the “Soviet Model” of development for its promotion of heavy industrial construction at the expense of light industry and agriculture along Bukharinist lines. At first glance, Kalain provides a compelling wrench to throw into the “two-line struggle” argument. However, he fails to provide a useful explanation for the developments in Chinese economic policy in the years he describes. In particular, why would Mao have gone from a “Bukharinist” position in 1956 to launching the Great Leap Forward in 1958?

This article will advance an argument for an understanding of Chinese economic debates, and particularly those between 1956 and 1962, in terms of a “three-line struggle.” This is a notion borrowed from David M. Bachman in Chen Yun and the Chinese Political System. This framing is opposed to the model of “two-line struggle” and to understanding Mao as a Bukharinist. It will particularly highlight the figure of Chen Yun as one whose role is especially illustrative to understand this period. This approach will reveal the Great Leap Forward to not have been simply a whim of Mao Zedong, but a case of his intervention into an existing bureaucratic struggle. The aim is a treatment of the dynamics of an “Actually Existing Socialist” society that goes beyond the standard focus on big personalities, or treating the state and ruling parties of such societies as either monoliths or as engaged in struggles limited to those between defenders of the communist faith and heretics. Rather, we will emphasize the conflicting bureaucratic interests and economic outlooks internal to the party-state, both to correct one-sided historical narratives, and to stress the importance of questions of state and civil institutional arrangements to future attempts to realize the emancipated society of communism.

The “Three-Line Struggle” Model

We will begin with a summary of the “three-line struggle” model. In his 1985 China Research Monograph, Chen Yun and the Chinese Political System, David M. Bachman lays out the ideas as well as the bureaucratic support groups of the “three lines” in Chinese economic debates preceding the Great Leap Forward. Bachman refers to the three groups as the “planning-heavy industry coalition”, the “extraction and allocation coalition”, and the “social transformation group.” The latter is referred to as a “group” rather than a coalition because its support was concentrated in the Party rather than across a handful of ministries.

The planning-heavy industry coalition was represented in speeches at the 8th Communist Party Congress in 1956 by Li Fuchun, Chairman of the State Planning Commission and Bo Yibo, Chairman of the State Economic Commission. It had a base of support in the heavy industrial ministries.3 The extraction and allocation coalition was represented at the Congress by Chen Yun, fifth-ranking member of the CCP and first Vice-Premier of the People’s Republic, Li Xiannian, Minister of Finance, member of the Politburo, and Vice-Premier, and Deng Zihui, head of the Party’s Rural Work Department and Vice-Premier. This coalition had its base of support in the ministries of Finance, Commerce, and Agriculture.4 The social transformation group was primarily based in the Party. It favored mass mobilization as a method for solving social and economic problems and was ideologically opposed to the divide between mental and manual labor, city and countryside, and worker and peasant. Its views were frequently espoused by Mao Zedong, Chairman of the Communist Party.

The planning-heavy industry coalition tended to favor higher rates of investment in heavy industry, direct allocation of goods by the ministries, and higher rates of extraction from the peasantry to finance capital construction. This policy served the bureaucratic interests of the ministries who supported the coalition. This was because it maintained their control over a larger portion of the social product, and created a closed loop in which the products of factories operated by a ministry would be allocated by that same ministry for new construction.5 These policies were a far cry from the policy favored by the extraction and allocation coalition, who controlled the taxation system, the budget drafting process, and the distribution of the products of agriculture and light industry.6 Due to its role in the distribution process and its contact with the working-class, and especially with the peasantry, the extraction and allocation coalition was highly sensitive to the new problems in the Chinese economy that had come along with the completion of “socialist transformation,” the previous focus of most bureaucrats, and shifted their focus toward these new issues. These problems included the over-extraction of grain from the peasantry, the supply problems related to the disorganization of production, and disproportion in investment that favored heavy industry over light industry and agriculture which led to shortages of agricultural products. They also pointed to the availability of too few consumer goods to satisfy the increased worker purchasing power that had come with recent wage increases, which threatened inflation in the short run.7 The extraction and allocation coalition thought that these problems had to be paid special attention, and that above all, rashness should be avoided. They tended not to think of the benefits of a planned economy in terms of rapid industrialization, although they affirmed the goal of a “strong, socialist country.” Instead, they focused on its ability to avoid the irrationality, disproportion, and destructive instability of capitalism. They thought that uses of the planning system that resulted in such instability and did not meet the needs of the population were abuses of this system. As Li Xiannian put it at the 8th Communist Party Congress, due to the existence of the planned economy in China:

…it is possible for us to pay attention to the connection between one year and another in a planned way, and to regulate the range of the year to year fluctuations, so as to avoid, as best we can, excessive fluctuations …. Had we been a bit more conservative last year and thus saved some raw materials and commodities, it would be helpful for working out the plan for 1957 …. We should gradually expand our material reserves . . . and thus ensure the even, smooth progress of our national construction, thereby further exploiting the superiority of a planned economy.8

This was a view that stressed evenness in development, rationality in planning, and the avoidance of a destructive level of fluctuation.

The extraction and allocation coalition favored moderate levels of grain extraction and increased investment in agriculture and light industry. They believed in the “three balances” of budgets, loans and repayments, and material production and allocation. They also advocated use of the market in distribution where the planning system did not yet have the requisite capacity to distribute all products, increased prices for grain to increase peasant standards of living and incentives for production, and larger private plots for peasants. They favored cutting investment in heavy industry in the short term, but thought that the increased revenue provided by the quick turnaround of investments in light industry would put heavy industry on a more solid basis in the long term.9 This was a far-reaching alternative to the policies that the CCP had hitherto followed. It stood in clear opposition to the program of the planning-heavy industry coalition.

Bachman argues that while this debate was raging through the state ministries, much of the Party, and therefore the social transformation group which included Mao himself, were too distracted by the ongoing Hundred Flowers campaign to pay much attention to economic matters.10 When they did pay attention, it was the planning-heavy industry coalition that was able to successfully make the case to Mao and the Party that its policies were superior. It promised to resolve what the CCP had declared to be the principal contradiction in Chinese society: the contradiction between the advanced “socialist” relations of production and the backward “underdeveloped” forces of production, while also addressing the inequalities in Chinese society that had persisted since the completion of “socialist transformation.” These inequalities had begun to worry Mao more and more.11

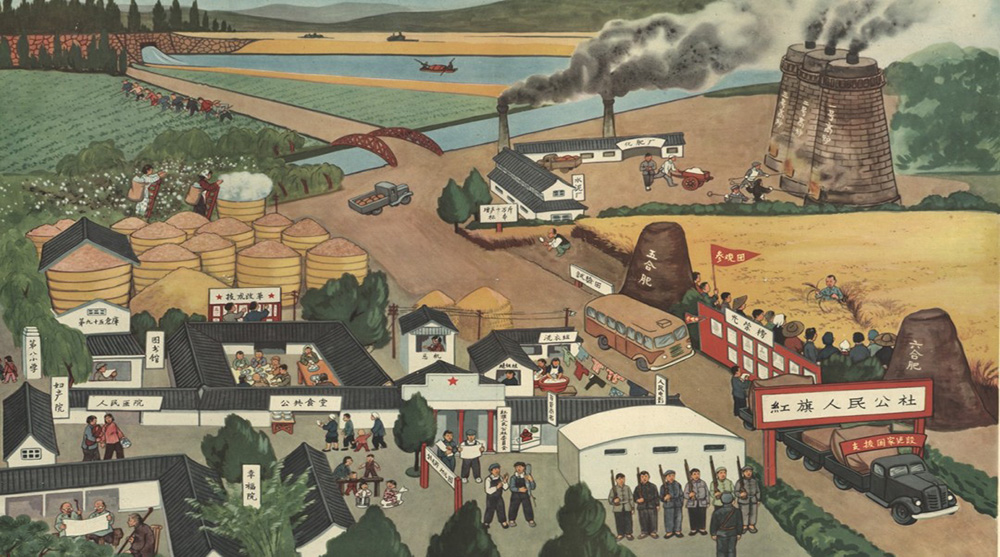

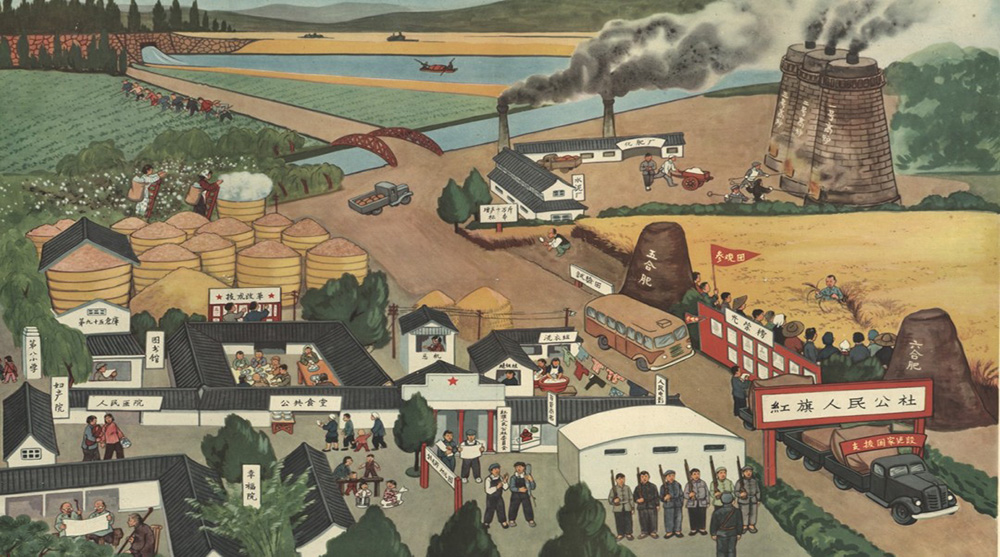

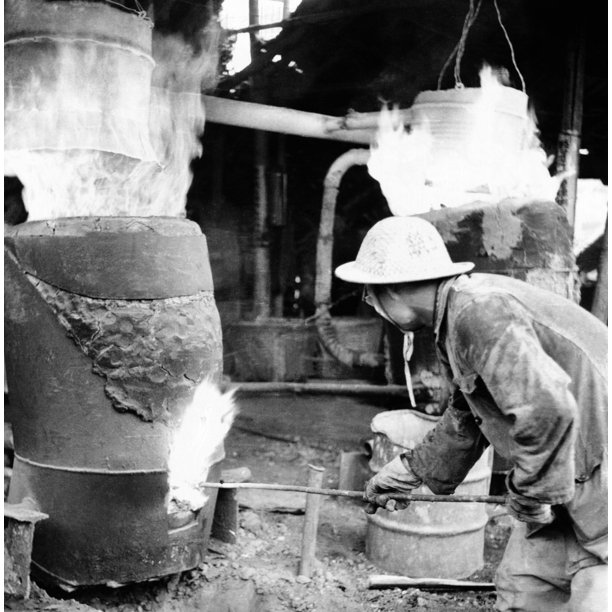

It was State Economic Commission Chairman Bo Yibo and State Planning Commission Chairman Li Fuchun who pioneered the approach that synthesized the preoccupations of the social transformation group with the policies of the planning-heavy industry coalition. This approach involved embracing the construction of small and medium-sized enterprises in the localities funded by the localities themselves; calling for greater efficiency in production through sheer voluntarism to make up for proposed cuts in light industry investment, and making up for cuts in the central investment in agriculture by relying on peasant labor mobilization and additional investment in heavy-industrial fertilizer plants. This would allow them to achieve their desired results of greatly increasing investment in large heavy-industrial plants while decreasing the external demands for heavy industrial goods by the localities. The localities would now be supplied by the small and medium-sized enterprises. The fears of Mao and the social transformation group about the divide between city and countryside, a divide which was growing as China industrialized, would be assuaged by bringing industry to the countryside, and the concerns about neglect of agriculture would be assuaged by advocating peasant labor mobilization. Mao rallied to this program at the Third Plenum of the Eighth Central Committee in September-October 1957. There, he summed up its ethos as “more, faster, better, and more economical,” and the Great Leap Forward was set in motion.12

The Great Leap Forward was not simply a whim of Mao Zedong, but the program of an alliance of bureaucratic interest groups. These were the planning-heavy industry coalition and the social transformation group, who had come together in the course of the “three-line struggle” in the Chinese state and the Communist Party. Their battle against Chen Yun and the extraction and allocation coalition would continue over the course of the Great Leap Forward. Chen conveniently claimed to have fallen ill between the Third Plenum and late summer-early fall of 1958, the period of the initial offensive of the Great Leap. He then gained Mao’s full favor between March and May of 1959, a period when Mao was more critical of the Leap. He supposedly fell ill again during the renewed radical phase of the Great Leap Forward between May 1959 and the fall of 1960. Chen only returned to prominence in 1961 as a leader of the economic recovery effort after the extent of the damage caused by the Great Leap Forward was undeniable.13

Assessing Mao’s “Bukharinist Phase”

After having undertaken a survey above of the “three-line struggle” in the economic debates occurring in the PRC before the launch of the Great Leap Forward, it should now be easier to assess the merits of R. Kalain’s argument in their 1984 paper, Mao Tse Tung’s ‘Bukharinist’ Phase. Kalain argues that Mao had a distinct “Bukharinist” period in the late 1950s that he abandoned by the time of the Great Leap Forward. According to Kalain, Mao’s views in this period were characterized by a preference for “a more balanced relationship between agriculture and industry in contrast to the Soviet model’s emphasis on heavy industry” and he “viewed agriculture and light industry as the foundation for the development of heavy industry and the economy in general.”14 Kalain claims that the core of Mao’s “Bukharinist” case can be found in his 1956 speech On the Ten Major Relationships, and in his works critiquing Soviet books on economics: Concerning Stalin’s Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR (1958), Critique of Stalin’s Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR (1959), and Reading Notes on the Soviet Text Political Economy (1961-62).15

One problem with this claim should be immediately clear. With the exception of the 1956 speech, all of these works in which Mao supposedly argues for a position which he had abandoned by the time of the Great Leap forward were written during the period of the Great Leap itself, that is, in the period 1958-1962. Kalain mitigates this problem by only using quotes from the 1956 speech, On the Ten Major Relationships16, in their paper. However, it is undeniable that the purpose of these later texts was to provide theoretical underpinnings for the Great Leap Forward. By looking at the text this picture becomes even starker. In Reading Notes on the Soviet Text Political Economy, Mao writes: “The vast majority of China’s peasants [are] ‘sending tribute’ with a positive attitude. It is only among the prosperous peasants and the middle peasants, some 15 percent of the peasantry, that there is any discontent. They oppose the whole concept of the Great Leap and the people’s communes.”17 It is difficult to see how this statement by Mao can be reconciled with Kalain’s claim about this text: that it represented a position that was opposed to the Great Leap Forward.

This should not prevent us from acknowledging that Kalain is not totally off base in including Mao’s early critiques of Soviet economics as examples of his “Bukharinism.” At points Mao’s critique does seem to line up pretty well with what Kalain describes as a “Bukharinist” perspective insofar as Mao criticizes the prioritization of heavy industry to the neglect of agriculture and light industry as well as the inequalities between the city and countryside. For example, in his 1956 speech, On the Ten Major Relationships, Mao indeed offered a more “Bukharinist” solution to some of these problems. He states that “The emphasis in our country’s construction is on heavy industry,” but claims that in the Soviet Union and in the People’s Democracies of Eastern Europe, “there is a lop-sided stress on heavy industry to the neglect of agriculture and light industry.” He claims that if more importance is attached to agriculture and light industry and a greater proportion of investment made in them “there will be more grain and more raw materials for light industry and a greater accumulation of capital. And there will be more funds in the future to invest in heavy industry.” On the subject of the extraction of grain from the peasantry he stated:

The Soviet Union has adopted measures which squeeze the peasants very hard. It takes away too much from the peasants at too low a price through its system of so-called obligatory sales and other measures. This method of capital accumulation has seriously dampened the peasants’ enthusiasm for production. You want the hen to lay more eggs and yet you don’t feed it, you want the horse to run fast and yet you don’t let it graze. What kind of logic is that!18

This should not be seen, however, as a new and distinct proposal for sweeping changes to the policies of the PRC or an argument for the abandonment of a whole economic model. Although Mao points out some problems with the economic policies of the PRC, in this speech he mostly counterposes China as a positive case against the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe as negative cases because of the PRC’s already prevailing lower rates of grain extraction in comparison with these other countries.

While Mao’s concerns on the balance in investment between agriculture and industry could indeed be called “Bukharinist,” because Bukharin paid considerable attention to similar problems in the early Soviet Union, and his early approach to these problems bore some resemblance to Bukharin’s, Mao’s ultimate solution to these problems in the Great Leap Forward was anything but “Bukharinist.” Again in Reading Notes on the Soviet Text Political Economy, Mao writes: “If we want heavy industry to develop quickly everyone has to show initiative and maintain high spirits. And if we want that then we must enable industry and agriculture to be concurrently promoted, and the same for light and heavy industry.”19 Unlike Bukharin, who advocated investing a greater share of revenue into light industry and agriculture, and using the faster turnover time on these investments to finance heavy industry; Mao proposed solving the disproportion in development between agriculture and industry and between light industry and heavy industry through initiative and high spirits. If we follow David M. Bachman’s “three-line struggle” model of the economic debates in the Chinese state and Communist Party, it becomes clear that Mao’s critiques in these later texts represent his social-transformationist concerns about the inequalities baked into the “Soviet Model” of development. And this mobilizational approach to the problem was precisely the program of the alliance between the planning-heavy industry coalition and the social transformation group that formed in opposition to the more “Bukharinist” extraction and allocation coalition.

Mao’s overall trajectory in economic matters in the late 1950s should not be seen solely in terms of individual innovation, that is, from an innovative Bukharinist policy to the innovative Great Leap Forward. Rather, it should be thought of in terms of Mao coming to actively intervene in an already existing bureaucratic struggle taking place within the state and the Communist Party. His position was initially closer to that of Chen Yun, one of his highest ranking economic advisors, and soon to be one of the leaders of the extraction and allocation coalition. Once the “three-line struggle” heated up and Chen became known as a partisan of the extraction and allocation coalition, though, Mao shifted his position to be in favor of the side that he felt had the superior program for industrialization and social transformation, that of planning-heavy industry coalition leaders Bo Yibo and Li Fuchun, in the Great Leap Forward, justifying this policy in his critiques of Soviet economics written between 1958 and 1962.

Chen Yun: Conservative Marketizer or Communist?

The departures Mao makes from the Soviet Model should not be understood as unique to him. Rather, as David M. Bachman argues, departures from the Soviet Model were precisely the sort of thing that Chen Yun had already been saying for years, beginning in 1954 in speeches he gave on the PRC’s first Five-Year Plan.20 The figure of Chen Yun is a relatively neglected one in the standard narratives of the PRC’s history. This is unfortunate because, in the actual political struggle that preceded the Great Leap Forward, the program of his bureaucratic coalition, the extraction and allocation coalition, was the only alternative proposed at the heights of the party leadership to the new course. It was also aimed at solving the broader problems that the Chinese economy faced after the successful completion of “socialist transformation.” At least in the English language literature, Chen Yun seems to have hitherto only attracted interest from supporters of China’s capitalist restoration. These tend to downplay his differences with Deng Xiaoping. They value him both as a leading champion of the market in the CCP for many decades and as a moderating influence on a process of marketization that ran into difficulties when it proceeded too rashly. This is certainly true of David M. Bachman, as well as of Nicholas R. Lardy and Kenneth Lieberthal, authors of the introduction to a collection of Chen’s speeches from 1956-1962 translated into English, titled Chen Yun’s Strategy for China’s Development: A Non-Maoist Alternative; and of Ezra Vogel, who wrote a biographical paper on Chen titled Chen Yun: his life.21

For example, Bachman stipulates in a number of places that Chen Yun was categorically not a “market socialist” of even the Yugoslav variety, and that he saw the market solely as a supplement to the plan. Bachman stipulates that in all cases Chen thought it should be subordinated to the needs of a socialist society, becoming the leading internal opponent of the Deng marketization after it went far beyond the measures he recommended.22 Yet, Bachman does not consistently portray Chen as someone with serious communist commitments that might lead him to come at the problem from a totally different perspective than that which motivated this latter process.23 Bachman makes an open-ended process of “reform” one of the key tenets of Chen’s economic thought and refers to him as on the conservative end of a spectrum of reformers that ends with Zhao Ziyang, the most aggressive of China’s marketizers.

However, Chen Yun’s economic thought offers something to those of us interested in the project of a planned economy as well. He offered a serious assessment of the problems that the Chinese economy faced after “socialist transformation” and proposed measures he thought would strengthen the overall planning system even if it required making limited use of the market. In both the Mao era and the Deng era he opposed every round of “overheating” forced on the Chinese economy, which usually carried detrimental consequences. This was in accordance with an overall view of the benefits of a planned economy which insisted that the goal of socialist planning was to serve the needs of the population in a way that avoided the violent disproportion and irrationality of capitalism. Lastly, he had a “bird-cage” model of the relationship between planning and the market, in which the bird is the market and the cage is the plan. If the cage is too small, the bird will suffocate, if there is no cage the bird will fly away. This metaphor offers an interesting light in which to view the plan-market relationship.24

Reflections

David M. Bachman’s “three-line struggle” model of the economic debates taking place in the CCP and in the state bureaucracy of the PRC preceding the Great Leap Forward is a useful lens for understanding the bureaucratic interests involved in the debate. It holds that the policies at the heart of the Great Leap Forward came into being as a result of an alliance between the planning-heavy industry coalition and the social transformation group in opposition to the extraction and allocation coalition. We have applied this model to assess the veracity of R. Kalain’s claim of a novel “Bukharinist” approach coming from Mao. We found this model to be insufficient because it confuses Mao’s social-transformationist concerns in his writings critiquing Soviet economics with earlier proposals that were in line with recommendations made in 1954 by one of his highest-ranking economic advisors, Chen Yun. We have also reassessed Chen’s legacy in light of scholarship that has cast him as simply a “conservative marketizer.” In contradistinction to this portrayal, we ought to emphasize his communist convictions and the usefulness of his thought to those attached to the project of a planned economy today.

Overall, this article has looked to explore the nexus of politics and economics in the PRC, going beyond cardboard cutout narratives of capitalist-roaders and genuine Marxist-Leninists still popular today, and to refine our understanding of the complex interplay of the two, taking into account conflicting bureaucratic interests and economic outlooks internal to the party-state. This has been carried out in the interest of correcting one-sided historical narratives of “Actually Existing Socialist” societies and for the benefit of future attempts at the realization of a communist project, stressing the importance of questions of the arrangement of state and civil institutions to the course of such projects.

- Meisner, Maurice J. 1986. Mao’s China and After: A History of the People’s Republic. New York: Free Press. p. 438

- For more on Bukharin, check out Cosmonaut’s translation of Amadeo Bordiga’s The Solution of Bukharin, the Cosmopod episode on Moshe Lewin’s Political Undercurrents in Soviet Economic Debates, and the Theoretical Review’s Reaping the Whirlwind: Soviet Economics and Politics, 1928-1932.

- Bachman, David M. 1985. Chen Yun and the Chinese Political System. Berkeley (Calif.): University of California. p. 105

- Ibid p. 113

- Ibid p.115

- Ibid p. 113

- Lardy, Nicholas R., Kenneth Lieberthal, Mao Tong, and Du Anxia. 1983. Chen Yun’s Strategy for China’s Development: a Non-Maoist Alternative. New York: M.E. Shappe, Inc. pp. 7-22 129-138

- Quoted in Chen Yun and the Chinese Political System p. 129

- Bachman p. 115

- In the Hundred Flowers campaign the CCP briefly encouraged open public criticism of itself and the state bureaucracy.

- Ibid p. 140

- Ibid pp. 132-135

- Ibib pp. 69-74

- Kalain, R. “Mao Tse Tungs ‘Bukharinist’ Phase.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 14, no. 2 (1984): 147–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472338485390111. p. 150

- Kalain p. 147, note 2

- Sometimes translated as On the Ten Great Relationships

- Mao, Zedong. A Critique of Soviet Economics: Transl. by Moss Roberts. Annot. by Richard Levy. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 1977. pp. 88-89

- Mao, Zedong. On the Ten Major Relationships. Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1977. Accessed through Marxists Internet Archive

- Mao, A Critique of Soviet Economics, p. 77

- Bachman pp. 53-56

- Bachman. Lardy, Nicholas R., Lieberthal, Kenneth, Mao Tong, and Du Anxia. Vogel, Ezra F. “Chen Yun: his life.” Journal of Contemporary China 14, no. 45 (2005): 741–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670560500206827.

- Bachman p. 96

- Ibid. p. 94

- Bachman. p 152