The typical medium through which political organizations have presented their vision of social change is the political program or platform. Despite lacking an official platform, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) has endorsed candidates that do have official platforms. DT Seel, using a method of induction based on the content of these platforms, proposes what the DSA’s program would be if based on the politics of its endorsed candidates. This ‘inductive program’ is then examined and put under critique.

DSA is notorious for lacking an official platform, which is both a strength and a weakness. It is a strength in that it allows fellow travelers to project their own images and understandings of socialism onto the organization. However, it also means that there is little shared understanding of what socialism is, and what needs to be done to get there. This is also reflected in DSAs extreme decentralization. Each chapter is an island unto itself, organized and run on whatever the dominant strain of left politics is in each locale. Some are organized and run by social democrats, some by communists, some by anarchists, and so on and so on. The resolutions passed at DSA’s convention (which I attended as a YDSA member) also provide little guidance, as several of the policy position passed have been brushed to the side by endorsed candidates (the endorsement of BDS and prison abolitionism to be specific). This understandably makes it quite difficult to discern what kind of political change DSA as a whole is working towards creating. Can we still figure out what DSA’s program is even within this heterogenous, often contradictory mass? I believe so.

The strategy I have taken to figure out DSA’s program is induction: drawing general principles from many specific examples. In this case, I have pulled together what I will call “DSA’s inductive program” by reading as many DSA endorsed candidates platforms as possible and drawing out common elements and themes. These candidates don’t have the same platform by any means but the platforms as a whole bear a family resemblance that lets us build a more-or-less representative whole. This, of course, won’t be an accurate representation of the politics of individual DSA members, but it is reflective of what the organization looks like from the outside. Even though many chapters do serious on the ground base-building work (especially in tenant and labor organizing), the sorts of stories that thrust DSA onto the public stage are about DSA’s electoral efforts. Julia Salazar and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez brought previously unheard of exposure to the DSA, and unless interested people find and churn through the dense web of online DSA discussion (it’s fair to say most do not) electoral campaigns are going to produce the common image of the organization.

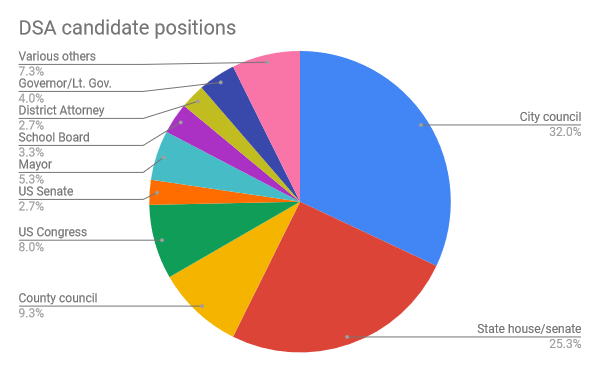

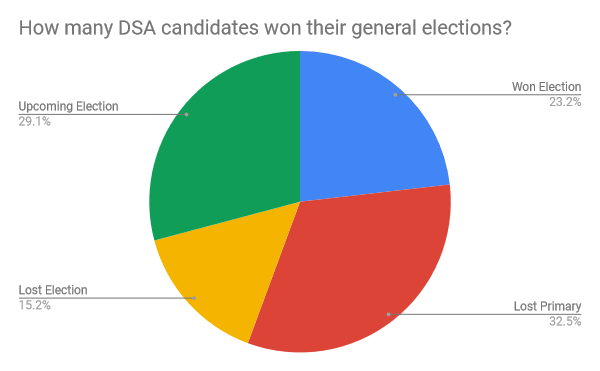

In terms of method, I searched social media and DSA chapter websites for candidate endorsements since the Trump bump (2017-now), and cataloged the candidate name, what political position they ran for, which chapters endorsed them, and whether they won their election (a large proportion of those candidates who made it through primaries in 2018 are up for election on today, 11/6/18). Most of these candidates were running for office in local, county, and state government, though there were 16 candidates running for both houses of Congress. Their geographic spread did not mimic the population density of DSA (for instance, the New York City chapter has endorsed 6 candidates and the Southern Maine Chapter has endorsed 9), but the candidates endorsed by larger chapters (Cynthia Nixon, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Marc Erlich, etc.) tend to get more attention in the press and on social media. This is all to say, there are some issues with this approach but it is well suited for a first approximation. You can find my data set here (please take notice of the notes to the right of the first two rows).

After I collected this data I read all the platforms I could find and attempted to synthesize common points, planks, and themes into a single program. This is what is meant by “DSA Inductive Program”. Though there were some contradictory points (especially on economic policy and rent control), the platforms were overall very similar in tone and theme. The main difference between each was the political focus: some candidates were more focused on health care, others on housing, others still on environmental issues, and so on and so on. In the Inductive Program, this results in a program that is the average of all those combined.

Many individual platforms were much stronger or weaker than the Inductive program below. For instance, compare that of James Thompson (a Democratic candidate for Congress from Kansas) to the platform put forward by Cliff Willmeng (a Green candidate for County Executive from Colorado. Thompson does not call himself a socialist and makes constant appeals to both nationalism and the interests of the capitalist class throughout out his platform (which contains mostly liberal-progressive measures). Cliff Willmeng on the other hand clearly identifies as a working-class socialist, and moreover states that “working people don’t need representation. We need to be building power and representing ourselves”. He uses his electoral campaign to put socialism and class struggle on the table, an effort that should be replicated as far and wide as possible. The goal of all our efforts should be to unite working people as an international class. We should thus evaluate electoral campaigns and the candidates themselves on this criteria: to what extent they are using their campaign to unite and strengthen the class as a whole. Electoral campaigns that serve to strengthen the position of liberal parties or the capitalist class are not victories, even if the winning candidate is a card-carrying socialist.

Before moving on to the program, it should be noted that we do not aim to imply that there should be no flexibility in adapting a program to local conditions. Adaptability to local conditions is essential for any successful campaign, electoral or not. What is of primary concern for working class people of Los Angeles is not the same as in New York or Durham. One group of folks might be in the midst of gentrification and seeking strategies to fight back against predatory landlords and developers, another might be trying to save a rural hospital from closure, and another might be trying to unionize their local logistics depot. It is true, as the saying goes, that we have to meet people where they’re at, but we also have to be able to move them to better politics. All of us started with a mass of contradictory liberal and reactionary ideas, but through the writing and teaching of others developed more sophisticated liberatory politics. The key is to connect all these local concerns and struggles to a broader framework of international socialism. If the socialist movement isn’t using electoral campaigns to advance socialist politics, then what exactly is it doing? All this being said, it is time to unveil the DSA Inductive Program:

Jobs and Economy

- The minimum wage should be a living wage of $15 or more (on essentially every platform)

- Protect and expand the right to unionize

- Enact a job guarantee

- Abolish right to work

- Enact just-cause termination protection

- Provide support for the transition to and creation of cooperatives

- Create municipal banks

- Create grants and support structures to encourage family owned business, small businesses, and entrepreneurs

- Subsidize entrepreneurship and new businesses

- Encourage consumers to support local and small businesses over large corporations

Housing

- Create land trusts and cooperative housing associations

- Enact rent control (some candidates, e.g. Danielle Meitiv, oppose this)

- Enact just-cause eviction protection

- Limit short-term rentals (i.e. Airbnb) through taxation or law

- Protect collective bargaining for tenants

- Enact a progressive property tax

- No sale of public land for housing development without a commitment to build affordable or mixed-income housing

- Housing development should be led by communities instead of developers

- Enact a vacancy fee for housing

Healthcare

- Build a single-payer healthcare system (on virtually every platform)

- Mandate paid sick leave

- Expand Medicaid access

- Expand accessibility services for seniors and people with disabilities

- Strengthen and protect Social Security

- Treat generic drug manufacturers like utilities

- Treat the opiate crisis as a public health problem, expand access to Narcan

- Build more healthcare facilities in rural areas, protect existing healthcare (including mental health) facilities from being shut down

- Spend more on preventative medicine

Transit

- Expand public transit, including bus rapid transit systems

- Build bike lanes

- Build light, commuter, and passenger rail

- Make transit more accessible

- Modernize America’s infrastructure

- Encourage the transition to green transit

Good Government

- Create transparent accountable local, state, and federal voting systems

- Shift to participatory budgeting where applicable

- Digitize budgets for great citizen involvement and oversight

- Build open data programs

- Shift to ranked-choice voting

- Shift to automatic voter registration

- Shift to public campaign financing

- Corporate money out of politics/No more lobbyist contributions/End Citizens United

- Enact term limits

- End gerrymandering

- Create a more progressive tax structure

Environment and Green Issues

- Transition to 100% green energy

- Make a Green New Deal

- Create municipal solar programs

- Create stronger protection of natural resources

- Phase out government owned gas vehicles in favor of electric vehicles

- Divest from fossil fuel companies

Civil Rights and Equality

- End the school-to-prison pipeline

- Create citizens review commissions with subpoena and disciplinary power over the police

- Funding, support, and protection for gender transitioning

- Adhere to racial, gender, and sexuality equality frameworks

- Make pregnancy and reproductive health a protected class

- Protect abortion rights, make sure abortion is free and on demand

- Enact laws guaranteeing equal pay

- Abolish ICE, end state and local collaboration with ICE in the interim

- Enact various gun control laws

Education

- Fully fund K12 education

- Create early childhood education programs

- Make public colleges and universities tuition free

- Support #RedforEd

- Increase teacher pay, increase school funding as a whole

- Increase the power of teachers to collectively bargain

- Increase funding for STEM education

- Limit or block charter school expansion

Imperialism

- End reckless wars

- Support the self-determination of Puerto Rico

- Support the self-determination of Indigenous peoples in the United States

All in all, this program is not very different from a typical progressive-liberal platform in the Democratic Party. For example, compare this to Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren’s platforms, or Indivisible-endorsed candidates such as Jess King or Anthony Flaccavento. This is not surprising, given that out of 125 candidates in partisan races, 102 of them were running as Democrats.

A program is not a wishlist of things that would be nice to have. It is a road map to building class power and to eventually overcoming the rule of the capitalists. It must provide the working class with a policy independent from capitalist parties like the Democratic Party. We will be resolutely clear on this point, that the Democratic Party is not a Labor or Social-Democratic party in decay, nor is it a neutral hollow shell to be filled with whatever left-wing politics are in vogue at the moment. The Democratic Party is a capitalist party whose rational actor strategy is to triangulate between the left and the right, to mediate and defuse upsurges in social and class unrest in for the capitalist class. I will not belabor this point, other than to say that as it was for the Populists, the Farmer-Labor movement, the CIO, the Civil Rights movement, and the CPUSA, the Democratic Party is still a force of conservatism. For an expanded analysis of this topic, see Robert Brenner’s “The Paradox of Social Democracy”.

Nonetheless, this inductive program based on DSA election campaigns is still worth considering as a minimum program for building the socialist movement rather than as a full plan for transition to socialism. It is particularly strong on the environment, tenants rights, and healthcare. These seem to be the areas where there is the most consensus inside the DSA. Very few people will argue against Medicare for All (except to argue it doesn’t go far enough), or tenant organizing, or the various green transition politics that have become common sense.

However, its silences and weaknesses are what is truly glaring. Though support does exist for some anti-imperialist stances, it is often couched in the discourse of strengthening America, supporting veterans, or opposing “unnecessary wars”. Few candidates go so far as to put forward an internationalist position, and none directly question the existence of the US Military itself. Most of the federal candidates sidestep the issue altogether or leave their position as a few short sentences about the treatment of veterans. The socialist movement is an internationalist movement, and the working class has no country. If DSA takes these principles seriously, then the lack of focus on imperialism and militarism is a large oversight.

The structure of the federal government is also a moot point in these platforms and the inductive program. Where it does come up, it is usually in the form of “good government” reforms reminiscent of the sewer socialists (or, as said before, plain old fashion liberals). While gerrymandering is tackled as an obvious anti-democratic practice, the structures of the government that allow the capitalist class to impose its will are left alone. There is still a lot to learn from the program of the old Socialist Party on this front. The abolition of the imperial executive, the abolition of bicameralism, the direct proportional election of all offices, the end of the dictatorship of the supreme court, and the national enactment of referenda and initiatives are a few (of many possible) easy targets. We should not lose sight of the fact that the US Government was built to stifle the politics of the working class. It was created to be a slow, conservative force in society. Enacting single-payer health care or free college tuition is all well and good, but we will not be able to protect those victories or advance further in the framework of the nation-state, and this nation-state in particular. We can’t lose sight of the fact that the US Government will never bring us socialism, even as we struggle to pare away its most poisonous elements.

The focus on appealing to small business owners, local businesses, and entrepreneurs is also troubling. Most of these platforms have one or another plank about subsidizing or encouraging these businesses, which is especially concerning given how few candidates have clear and open identification as socialists. These pro-business positions sit uncomfortably with planks in favor of fight for $15, support for stronger unions, and support for more labor rights. Small business owners are often the vanguard of reactionary economic positions, they are the lower strata of the capitalist class that fears it will lose its property and be converted into workers, having to get a job just like the rest of us. It’s a banality to support small business owners and entrepreneurs in America, but it’s a curious position for socialist candidates to take: it puts them at the intersection of contradictory class interests. The small business owners you subsidize and promote one week will be the donors to right-to-work campaigns, to politicians who seek to block a $15 minimum wage, to all manner of union-busting politicos and PACs. The interests of the capitalist class and the working class are opposed, to support even the lowest strata of capitalists is to undercut your own struggle for socialism.

That brings me to my last point of criticism of the program: the sparsity of labor politics. Few candidates put forward specific proposals for strengthening labor unions, though many make statements in favor of labor in principle. In particular, support for #RedForEd, anti-right to work policies, and expanded bargaining rights for teachers unions are high points of many of these platforms. Likewise, the support for workers cooperatives is a welcome development. It needs to be said that they are not a solution to capitalism nor do they create islands independent of market forces, but they are still, like labor unions, important for the self-development and defense of the working class.

Nonetheless, it is surprising that little attention was paid to, for instance, Taft-Hartley (which, it is worth noting, was passed by the Democratic Party to reduce the chance of working class insurgency against the Dems). Taft-Hartley still provides the state and the capitalists with some of their most potent anti-union tools. The legalization of solidarity and political striking, card check, and the repeal of its right to work measures should be top priorities for socialist politicians. Likewise, measures should be taken to protect the right to strike (including wildcat strike) in general. While there are some promising elements in individual platforms (Sarah Smith, in particular, has strong positions on worker’s rights and unions broadly), there is a lot of room for improvement on this, especially given the importance of labor to the socialist movement and the emphasis some sections of DSA have put on a rank and file strategy.

Many of the issues that are reflected in the weakness of this program are produced in part by the structural location of DSA: its international context, its internal communication and power structures, and its relationship to the Democratic Party. The DSA has weak connections to other socialist formations throughout the world, having left the (corrupt and outdated) Socialist International. This has left DSA without formal affiliation with any international grouping of socialist organizations. This allows the DSA to take a more inward-facing view, rather than looking at itself as a component piece of an international whole. Where international affiliations do exist, they are generally the productions of personal relationships or professional networking. There are few opportunities to interact with other socialists from around the world, and programs such as member exchanges are seemingly non-existent (or are not disclosed to the rank and file).

The internal structures of DSA also preclude a great deal of political development. While the federated structure allows for a great deal of experimentation and sensitivity to local conditions, it also makes it difficult to spread information quickly and effectively or make democratic decisions as a whole body. There also seems to be no full account of the candidates endorsed by DSA, except for documents compiled unofficially by individual members. Lessons that are learned in one chapter are unlikely without great effort to be internalized by the organization as a whole.

Candidates who lose their elections are effectively given a damnatio memoriae, their names struck from DSA press and social media and are rarely thought of again. The speed with which DSA members quit talking about Jabari Brisport and Kaniela Ing within its online forums is still incredible to me. Lessons gleaned from their campaigns and painful failures that need to not be replicated are not communicated to the organization as a whole. Furthermore, because of the decentralization of the organization, large chapters (such as New York City, Philly, and East Bay) have oversized sway over the way DSA presents itself to the greater world, and what sorts of projects the organization as a whole work on.

A recent example of this is the endorsement of Cynthia Nixon. In this case, the endorsement of a candidate by one (albeit enormous) chapter resulted in outsiders believing that the organization as a whole endorsed this candidate when it emphatically did not. The correct balance between centralization and decentralization has yet to be reached in DSA. This results in large chapters (or dominant factions within those chapters) dominating the organization as a whole without any greater accountability, to the detriment of both their smaller neighbors and the DSA as a whole.

The relationship to the Democratic Party and electoral politics as a whole produces distorting effects in the DSA. Electoral politics should be viewed, with an enormous grain of salt, as a reflection of the success of socialists in organizing broader society. DSA victories alongside victories of a broader liberal-progressive range of candidates may indicate that DSA is surfing the waves made by deeper social forces rather than tapping into a resurgent desire for socialist politics in particular. There is no way to know in the short term, so it is important not to conflate the success of DSA candidates at the ballot box with the success of socialist politics or the working class, especially when the meaning of “electoral success” has been so theoretically underdeveloped.

Electoral “success” is not power in and of itself—we must have the power to enact and defend a socialist program. If we are riding a momentary wave with little substantial independent power to back us up, anything enacted will be swept away by the later upsurges of liberals and reactionaries. In order to guarantee we have stable, lasting power we need not view contesting elections as our primary task, but as flowing naturally from building independent working class power. All roads to power are difficult, treacherous and uncertain, but we need to build a social base to even begin thinking about seriously taking part in the political sphere. Thankfully, many DSA chapters are already doing good work in this regard, especially the tenant organizing of Portland and Los Angeles DSA, to give a specific example.

Lastly, it is worth thinking about the social position and incentives presented to DSA endorsed candidates themselves. For newly minted socialist politicians in the Democratic Party, there are powerful incentives to move to the right, triangulate against the DSA, and pick up a new social base with a few stacks of cash along the way. Without an independent socialist political infrastructure, candidates will be dependent on staffers and analysts wholly ingrained in the present system of governance. DSA does not currently have the capacity to provide for all the funding, staffing, and policy needs of an entire substratum of new Democratic Party politicians. It almost certainly lacks the strength to keep these politicians from drifting rightwards, especially given the relative power of the DSA versus the core of the Democratic Party bureaucracy and its power base. This kind of organizing must go far deeper than elections in order to be effective: it involves building a whole political structure and bringing up our own candidates through it.

There have been many internal discussions in the DSA about the concept of accountability, but the fact remains that until DSA builds a party infrastructure all of its own, its candidates will be accountable to outside interests rather than the socialist movement itself. It’s a basic fact of dropping individuals into long-standing deeply entrenched institutions. There are very few who can keep their principles during the long march through the institution. This dependence on the wider liberal-progressive political apparatus also limits the ability of the candidates to pursue unconventional strategies and tactics. They will be expected to fill a traditional role and will be unable to pursue obstructionist, abstentionist (refusing to fill seats), and propagandistic strategies as the case may call for. In an age of alienation, disenchantment, and political cynicism it is crucial to not limit our options to the ones that the liberal order has already deemed acceptable: it may be just as necessary for socialists to be anti-politicians in anti-political situations as it is to push labor politics during times of heightened class struggle or a national health service when capitalist health care is obviously failing.

We can learn many lessons on this from the old socialist movement who, in contrast to crude economistic histories, built vibrant, flexible organizational ecologies. The old workers’ movement built trade unions, but it also built tenants unions, media organizations, mutual aid societies, socialist gyms and fitness clubs, collective child care associations, etc. We aren’t just building new labor unions and parties that appeal to narrow economic reason, we are building a whole social apparatus and culture that enables its participants to see beyond the constraints imposed on them by capitalism. It gives them the chance see the morning sun of socialism rising above the dark horizon. Our program must appeal to people’s sense of interest, but our organizations must give them a reason to fight for it.

The problem of the socialist program is a complex one. The programs of the early socialist parties were developed and sharpened after decades of struggle and were adopted as new lessons were learned. We are living in the shadow of the failure of 20th-century socialism, so it is not surprising that we have a spectral socialism with as many contradictions and half-measures as signposts to the future. These are all problems that will be sorted out in the course of the struggle, in the course of debate, and in the course of experiment. This is a time of revolutionary patience. We are at the beginning of a new journey, we must carry on the lessons of those who went before us but we must also make our own path. In this spirit, the upsurge of socialist politics, even limited and contradictory socialist politics, is a heartening and welcome development as it gives us a new footing to rebuild the socialist movement here and now.

“Our demands most moderate are—

We only want the earth!”

—James Connolly, 1907