Gary Levi responds to Joshua Lew McDermott’s “Two Myths About the Working Class,” arguing against dogmatist conceptions and articulating the conditions of ongoing class development.

Indra Dodi, Note No.1 (2019)

The first chapter of The Communist Manifesto opens: “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” An entire complex of debates among interpreters of Marx, as well as critics, has been over classes as basic units of social analysis. These debates are best understood as not primarily over interpretation of “hitherto” existing society, but instead (frequently) as proxy debates over the nature of capitalist production, and over the correct strategic orientation for socialists. Following Marx, our goal should not be to understand class as a sociologist might, as a unit of pure analysis (as the saying goes, “as a bug under glass”), but as formations thrust into conflict by the very relations of production — and further, to understand these conflicts as ones in which socialists have a distinct side. This is to say that class is the question of who rules society today, in what interests, and against what other interests, and who we desire to rule society instead.

Challenges to the Marxist theory of class come in a few varieties. One, advanced by people like Erik Olin Wright, is to dissolve the understanding of class as a relation to production into a generalized fine-grained analysis of “rights and powers people have with respect to productive resources and economic activities.”1 Another, which has appeared in a variety of ways since at least the 1940s, is to discover that production has changed so significantly in one or another way that the class divisions that Marx pointed towards as the dominant ones of capitalist society (bourgeois and proletarian) are no longer accurate. In the 1940s, this was exemplified in Burnham’s managerial class,2 followed by the Galbraith’s “New Class” in the ’50s.3 Still other analyses of class include the “cybernetic revolution” of the Triple Revolution memo in the ’60s (signed by Todd Gitlin, Tom Hayden, James Boggs, Norman Thomas, and Michael Harrington among others)4 and the Ehrenreich’s Professional-Managerial Class in the 1970s.5 Others contended in the 1980s that the capitalist class had transformed through “financialization,” while in the ‘90s various accounts of “globalization” transformed both classes.

Joshua Lew McDermott’s recent Cosmonaut article “Two Myths about the Working Class” raises some useful correctives to certain vulgar approaches to class, and presents an agreeable conclusion: the need to organize informal workers. McDermott presents an answer of sorts to the second form of criticism, arguing the social and economic changes of the past half-century have not reduced the importance of the working class, but simply placed increased importance on other groups of workers that are perhaps less “traditional” (but are in all important respects still working class). However, in so doing, it at times bears the risk of losing sight of why Marx distinguished the working class as significant, or why we should do so today — reducing analysis to a question of numbers rather than social position, and neglecting the distinct and unique role in socialist thought that the working class plays as the class which must govern society. Further, it accepts and repeats some dubious economic claims that were pioneered by “anti-working-class theorists”. This article will attempt to treat both issues in a friendly spirit, taking off from McDermott’s article to address some widespread debates regarding class.

Social Power

The first of two issues that McDermott tackles is the “industrialized proletariat myth,” objecting to “a tendency, whether latent or explicit, of recognizing industrial labor as the defining form of labor in capitalist society, and thus industrial workers as the working class par excellence.” This is not simply fighting phantoms. There are those who have dismissed organizing at Starbucks because baristas are not “real workers” (I invite such critics to take jobs there and see if they still agree), and more generally there is a sense that “real labor” is restricted to jobs involving physical labor with large machines. Thankfully, the progression of modern labor organizing has been leaving such views behind. In my experience, those most likely to repeat such things these days are not leftists of any stripe. They are bosses, or lackeys of bosses, trying to tell workers who are organizing that “unions are for them, not for you”. This is to say that such myths are used to drive wedges between workers and to con them into thinking that they are not workers, destroying solidarity and disrupting organizing efforts.

However, a confusion of categories arises in McDermott’s ensuing argument. The reason non-industrial workers are workers is simple. They are employed by capitalists, and they are paid by the capitalists for only a portion of the total work they do, with the remainder of their labor being appropriated by the capitalists in the form of profit. McDermott goes further, and instead raises an argument about the location of working-class power, arguing that it is wrong to situate that with certain manufacturing and logistical industries. Just as with the objection to the term “lumpenproletariat” (more on this later), McDermott takes issue with analysis of concrete material circumstance not on the basis of analytical differences, but because it is confused with a moral value-judgment.

To return to the Starbucks workers as an example — some of these workers are very conscious and militant. Their struggle has been heroic, determined, and inspiring to a whole wave of new organizing. It has been invaluable to the last few years of labor upsurge.6 They deserve every ounce of support they can get – for their sake, and for all of ours. However, it is also simply a fact that these workers have less social power than UPS workers, despite the fact that UPS workers did not engage in a heroic wave of organizing this last year. Rather, militants within the union had their hopes dashed by a supposedly militant leadership, backed by the longtime reform caucus who engaged in closed-door negotiations and drastically retreated on its wage demands for part-timers.7

Recognizing that UPS workers have more social power than Starbucks workers is neither a value judgment nor a reason to be dismissive of organizing in either location. It is simply recognizing that UPS workers handle packages every day whose value is roughly 6 percent of the entire U.S. gross domestic product. A ten-day UPS strike could have cost more than seven billion to the U.S. economy.8 By contrast, a ten-day strike across all Starbucks would have cost the company roughly 2/3 of a billion in gross profit, with minimal economic disruption more broadly.9

This differentiation in social power is on a society-wide scale, not a local scale. To a crude approximation, a ten-day strike at any company will cost that particular company ten days of profit. The social power workers hold with regards to their own boss will vary by their mass and skill (which are factors in, essentially, their ease of replacement). On the other hand, the social power of workers with regards to society as a whole will vary with regards to the character of their work and its centrality to the overall functioning of the economy. To the extent we wish to support workers in fighting to improve their own pay and conditions, it is the former that matters. But we also would like, in time, for workers to take up broader causes beyond their immediate economic and workplace concerns, and to step into the political arena as a class. For example, in opposing racist police terror or defense of abortion rights. There, it is society-wide social power that matters and we ignore it at our peril.

McDermott confuses an assessment of social power with an assessment of which struggles we should care about. On the latter, there is very much a correct target. Too often, there are arguments that organizing in small shops, or hot shops, or service sector jobs, or contingent academic jobs, or so on, is “not strategic.” In the long run, such workers have limited power, to be sure. But in the medium- and short- term, as with Starbucks victories, those campaigns can have an enormous and outside galvanizing effect on far larger layers. These efforts can also serve as training grounds or trials-by-fire for new generations of organizers. Struggle and consciousness develop by leaps and strange connections, and history shows that victories for workers rarely arise by a straight line.

Numbers, Power and Industry

In the most frustrating passage of the article, McDermott goes on to argue that not only is it somehow “privileging” to attribute particular power to industrial and logistic workers, but in fact that these workers have less power than ever before, due to “the rise of global labor arbitrage and the attendant deindustrialization and weakening of the labor movement throughout the global North since the 1970s” which in fact “remains nothing short of an existential crisis for classic socialist theory and praxis.” He then poses the question, “If the only hope for the socialist revolution lies in a structurally powerful industrial class, what hope remains in the wake of deindustrialization and the shift towards post-industrial service economies in today’s late neoliberal era?” There are at least four things to disagree with here, and each will be treated in turn.

The first problem is the argument that the industrial working class is numerically weaker, and so therefore, we must find social power in the grouping that is numerically stronger. This is a confusion of power with numbers. The strategic nature of certain sectors of the working class, as discussed above, is not in its quantity, but in its centrality to capitalist production. In fact, the whole notion of strategic social power is precisely that relatively small numbers of workers at certain “choke points” (such as production of essential goods or logistical centers like ports) can play an outsized role in the economy as a whole. Consider, for example, the impact to the entire global economy caused by the Ever Given getting stuck in the Suez Canal in 2021 – which impeded roughly $10 billion of global trade a day over six days.10 The workers who keep the Suez Canal running are at a (quite literal) choke point to world trade and have significant power. The history of the Suez crisis, the subsequent management of the canal and its workers, and its oversight by a highly militarized state apparatus (which in turn operates under the threat of imperial intervention) all stand in the way of this power being exercised. Nonetheless, the overall point remains — the power of small groups of workers may be vastly disproportionate to their numbers, and it does us no good to ignore this.

More generally, there is a certain logical economic priority to some occupations over others. This can be analyzed in great detail: for example, starting with the two-sector model of reproduction in Volume II of Capital, distinguishing between “Department I,” consisting of the production of means of production (and hence concentrated in heavy industry) and “Department II,” consisting of the production of articles of consumption.11 But at the most broad level, let us consider a “prototypically service” job, such as at a pizza joint. For a worker to serve a pizza, there must first be a pizza. That in turn requires, these days, the use of expensive and commercial-scale kitchen appliances — from mixers to ovens and dishwashing machines — all products of industrial manufacture. Further, these machines must be powered, requiring both the generation (a large-scale industrial endeavor in itself) and the transmission of power (a prototypically skilled proletarian occupation). Then we come to the issue of ingredients – produced on large-scale farms using complex modern equipment (perhaps manufactured by UAW members at John Deere or the like), then packaged and distributed through supply chains making use of logistical workers, who in turn operate still further forms of large-scale machinery (which themselves require production!) Behind every service job lies an entire chain of accumulated value which must be produced and reproduced through industrial labor.

While the total output of U.S. manufacture is very strong by all measures, the absolute number of workers engaged in manufacture has indeed diminished considerably, down to about 12 million from its 20 million peak in 1979.12 This has important consequences for how we go about organizing; it does not make manufacture less strategic or important. If anything, the dwindling of workers while profit and output continues to rise points to a further concentration of power in the workforce that now exists, as a greater share of profit and output is attributable to each individual industrial worker. It also highlights the glaring disparity between the pay and conditions of such workers, and the vast wealth extracted from them by the capitalists, as well as the importance of the struggle to shorten the workweek while preserving pay — so as to spread employment out to all those who seek it.

Consciousness

The second problem in McDermott’s passage is the neglect of reasons why socialists pay special attention to the working class beyond simply power and numbers. Here, we should note that the working class in Russia at the time of the 1917 revolution, despite the intensive growth of industry over 30 years, was small compared to the size of the working class in any major capitalist power today. The Russian proletariat also was not as large as the working class in many of the contemporary imperialized neo-colonies of the so-called “periphery.” Lenin’s The Development of Capitalism in Russia cited the 1897 census of the Russian Empire, which showed that there were roughly one fifth as many workers in industrial and commercial employment as in agriculture. He concluded, “This picture clearly shows, on the one hand, that commodity circulation and, hence, commodity production are firmly implanted in Russia. Russia is a capitalist country. On the other hand, it follows from this that Russia is still very backward, as compared with other capitalist countries, in her economic development.”13 The relative numerical weakness of the working class did not prevent Lenin and the Bolsheviks from orienting towards it, nor did it prevent the workers from playing an outsized role in the Russian Revolution.

During the early years of Russian Social Democracy in the 1880s and 1890s, a central struggle was establishing theoretically and empirically the distinct role that the industrial working class would play in Russia, especially against agrarianist Narodnik and anarchist views. In contrast to Western Europe, where the growth and importance of the industrial working class were empirically incontestable, the case had to be made in the less economically developed example of Russia. Hence, Plekhanov argued in an 1899 speech to the International Workers’ Socialist Congress in Paris against viewing “Russia as a kind of European China, whose economic structure has nothing in common with that of Western Europe.” Directing attention towards the development of manufacture, under the spur of the autocratic government, he concluded: “The industrial proletariat, whose consciousness is being aroused, will strike a mortal blow at the autocracy and then you will see its direct representatives at your congresses alongside the delegates of the more advanced countries.”14

By turning to the writings of Lenin and Plekhanov, we can find an especially strong case for the importance of the industrial working class for social and not merely numerical reasons. Plekhanov’s 1883 “Socialism and the Political Struggle,” a founding text of Russian Social Democracy, is largely devoted to this question. His subsequent 1885 “Our Differences” emphasized the specific consciousness induced by capitalism in the working class as a key element in its significance: “Capitalism broadens the worker’s outlook and removes all the prejudices he inherited from the old society; it impels him to fight and at the same time ensures his victory by increasing his numbers and putting at his disposal the economic possibility of organising the kingdom of labour.”15

Plekhanov’s arguments, following Marx, were not simply that the working class has the power or numbers to overturn the capitalists, but that its material circumstance has made it uniquely suited to govern as the “universal class”: that class, shaped by the capitalists themselves, which is particularly suited to fight for and govern for the interests of all. Conditions of large-scale production are what shape the proletariat into such a universal class — particularly the concentration of workers, the equalization of their conditions, and the increasingly and necessarily collective nature of its struggles – all thrust up against the flux of capitalist markets, which throw workers’ livelihood into precarity. All of this compacts the workers into an entity that sees itself as a class; circumstances are brought about where clashes between individual agents become instead clashes between classes in contention.

Plekhanov also quotes the Manifesto in picking out why other classes do not possess such qualities:16

The lower middle class, the small manufacturer, the shopkeeper, the artisan, the peasant; all these fight against the bourgeoisie, to save from extinction their existence as fractions of the middle class. They are therefore not revolutionary, but conservative. Nay more, they are reactionary, for they try to roll back the wheel of history. If by chance, they are revolutionary, they are only so in view of their impending transfer into the proletariat; they thus defend not their present, but their future interests, they desert their own standpoint to place themselves at that of the proletariat.

This latter point is why we should be wary of attempts (such as McDermott’s) to widen the definition of working class to the poor and dispossessed more generally. McDermott objects to “recognizing industrial labor as the defining form of labor in capitalist society, and thus industrial workers as the working class par excellence.” We need not limit ourselves to industrial labor, of course, but we should recognize that by Marx’s approach what distinguishes a group in society as strategic is not merely numbers and not merely power, but also the material circumstance that shapes their consciousness — their compaction and coherence, and, in a sense, their distance from the artisan and peasant who wage a conservative fight to defend their present rather than “future” interests.

Deindustrialization, Neoliberalization and The Rest

The third problem with the “neoliberalism” passage from McDermott is its broad accordance of credence to some very impressionistic claims about structural changes in the world economy, ones that were prevalent in the 1990s but that history has shown to be quite facile. Unfortunately, while modern economic thought has moved on, the broadly “Marxist” theorizations stemming from it have quite a bit more staying power.

McDermott writes of the “deindustrialization and shift towards post-industrial service economies.” Deindustrialization as a shift in the world economy simply did not occur. It was made up. Even if we posit the “global North” had undergone deindustrialization, that would simply mean much vaster shifts of production elsewhere which would still involve industrial manufacturing conducted by a large, powerful industrial proletariat. The world economy produces more things, with more condensed labor, than ever before. By World Bank figures, the amount of value added by global manufacturing has roughly tripled since 2000.17

It is not even the case that production has shifted from the “global North.” Rather, the growth of new manufacture throughout the neocolonial world has been complementary to the continued strength of manufacture in major imperial powers, not parasitic. Global supply chains involve at times, as with electronic goods, production of components or refinement of raw materials abroad and their assemblage in specialized plants in the major powers. At other times, as with automobiles, supply chains involve the manufacture of higher-level integrated components in major industrial powers, with final assembly performed in the country where the product is to be sold. Since 2000, manufacturing profits in the U.S. have skyrocketed from roughly 100 billion to 750 billion, — hardly a sign of a “deindustrialized” economy.18 In fact, the U.S. has in the past decades, increased or kept stable its share of manufacturing with regards to rival capitalist powers in Europe and Japan. It is simply the case that China has undertaken a massive growth in manufacture and now constitutes 30% of all global manufacturing value added, far outstripping the major imperialist countries.19 But the nature of the Chinese state or economy are outside the scope of this article.

This is not to deny that shifts have occurred. Even so, it is important to locate and understand them precisely. One must realize that the common narrative, which McDermott unfortunately accepts, has had a particular ideological valence. It has been especially promoted by those who wish to argue that Marxism is outmoded, and that we cannot locate in the working class any social power or hope for social progress. In particular, deindustrialization as a global or national phenomenon is simply untrue. But deindustrialization as a local or regional phenomenon is beyond doubt. In America, this is exemplified by Detroit and other decaying Rust Belt cities.

It should be understood that deindustrialization is not a new or modern phenomenon that is to be located only in the “late neoliberal era”. Rather, it is something that has been a feature of capitalism since its birth. Capital is highly mobile. From the Manifesto, again:

The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the entire surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere…. All old-established national industries have been destroyed or are daily being destroyed. They are dislodged by new industries, whose introduction becomes a life and death question for all civilised nations, by industries that no longer work up indigenous raw material, but raw material drawn from the remotest zones; industries whose products are consumed, not only at home, but in every quarter of the globe. In place of the old wants, satisfied by the production of the country, we find new wants, requiring for their satisfaction the products of distant lands and climes. In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal interdependence of nations.

Once one of most of the vibrant sites of industrial production in the U.S., Paterson, New Jersey, famous for the silk strike of 1913, was devastated by the 1929 depression. It never fully recovered.20 Similar examples abound, well prior to the “era of deindustrialization”. In Britain, the cotton industry as a whole similarly reached peak production in the 1910s, and by 1955 was exporting less than a tenth of the cloth it had before.21

Capital constantly moves; it constantly revolutionizes. It builds up whole sectors, then abandons them when the winds of profit shift. While today we see the Rust Belt cities of the Midwest, a trip through the northeastern seaboard will reveal plenty of decayed industrial towns as well, built and abandoned in former eras. Where and how investment is funneled is not something purely external to the working class, facing us like a force of nature. On the contrary, it is a product not of blind market forces, but the class struggle itself. Scholars of what has been described as “post-Fordist” manufacture have described how the shift from the vast auto plants of the heroic period of the UAW was a conscious reaction by the capitalists to the militant struggles of workers. A broader network of smaller plants meant less opportunities for workers to collectively organize and develop militant consciousness. The distribution of manufacture among many smaller subcontractors allowed the big three to divide the workforce among many employers and weasel out of union contracts.22

While McDermott and many others who speak of a “post-Fordist” or neoliberal shift in production point towards the 1970s, there has been a constant flux in capitalist production between centralizing and decentralizing forces. A key work in this regard is Sugrue’s The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Post-War Detroit. which documents well that “the rusting of the Rust Belt began neither with the much-touted stagflation and oil crisis of the 1970s, nor with the rise of global economic competition and the influx of car or steel imports. It began, unheralded, in the 1950s.”23 Some of this was rooted in the WWII military production boom itself, overseen by the corporate executives appointed by Roosevelt to the War Production Board, who took the opportunity to reshape the geography of manufacture to their liking (specifically away from union concentrations). In major urban areas, new investment was located outside of central cities more than twice as heavily as before the war.24

Sugrue’s work importantly connects industrial shifts with not only labor struggles, but racial oppression and segregation. In both the birth and decline of the industrial Midwest, we also see the coupling of race and class. Henry Ford consciously sought a racial and ethnic balance among his workforce to keep groups competing and divided through the mass migrations northward of black workers. African Americans first were seen as a pliant labor force willing to work cheaper with less complaint, then later became viewed by management as a threat whose demands for equality, better pay and safer conditions threatened to upend manufacture. Manufacture shifted from the heavily segregated cities to the white-flight suburbs. As Sugrue documents, “Between 1947 and 1958, the Big Three built twenty-five new plants in the metropolitan Detroit area, all of them in suburban communities, most more than fifteen miles from the center city.” Supporting manufacturing firms acted likewise: “Between 1950 and 1956, 124 manufacturing firms located on the green fields of Detroit’s suburbs; 55 of them had moved out of Detroit.”

In subsequent years, while the industrial base of Detroit proper was vastly diminished, the entire region remains one with an outsized amount of manufacturing. It is just that such manufacturing is distributed among many smaller plants, often in places inaccessible to the black workers who were left abandoned in the urban core. Similar but different stories played out in other urban sites of heavy manufacture as well.

Beyond just intra-regional manufacturing shifts and transfer, there has also been an overall shift of manufacture towards the former slaveholding South to and the so-called “Sunbelt States”. This too was a deeply racial phenomenon. The legacy of slavery and Jim Crow meant that the south was a stronghold of “right-to-work” open-shop laws, preventing unions from compelling workers to join. Capital was not simply fleeing to find better transit infrastructure or access to cheaper energy. It was seeking to find a foothold where it could push back on the gains of labor. New industries, such as semiconductor manufacture, developed from the start in Texas and Arizona for similar reasons. For labor to crack the open-shop South meant fighting against the bosses directly, but also against deeply entrenched racial divisions among workers, which the bosses continue to foment. The labor leadership of the time, a conservative product of the Cold War Red Purges, had no capacity or vision to wage such battles.

The decline in the U.S. labor movement pointed out by McDermott was not an inevitable product of shifts in the world economy. Rather, it was the impact of class war by the capitalists coupled to the mercurial, mobile, and constantly revolutionizing nature of capital itself, and most importantly, the destruction and displacement of a generation of militant trade union activists and leaders who could have fought back. Labor need not be prostrated before plant closings, production and technology shifts, and the like; the old-guard Cold Warriors preached just that and left their membership at sea. By contrast, the recent UAW strike and its outcome has given at least a little vision of how a fighting labor movement really can answer the bosses — clawing back, for example, the right to strike over plant closings.

The “Service Economy”?

Finally, the fourth problem with McDermott’s description of the world economy is its description of a “shift towards post-industrial service economies.” Deindustrialization occurred as a local or regional phenomena, but not a national or global one. However, it is still possible that there was an overall growth of the service sector dwarfing that of the industrial, and thus a general dwindling, in some sense, in the importance of industrial manufacture. There is some evidence for this: over the same period, the value of global manufacture tripled, its weight as percent of GDP declined from 18 to 16%.25 Does this point to a “service economy” or another phenomenon?

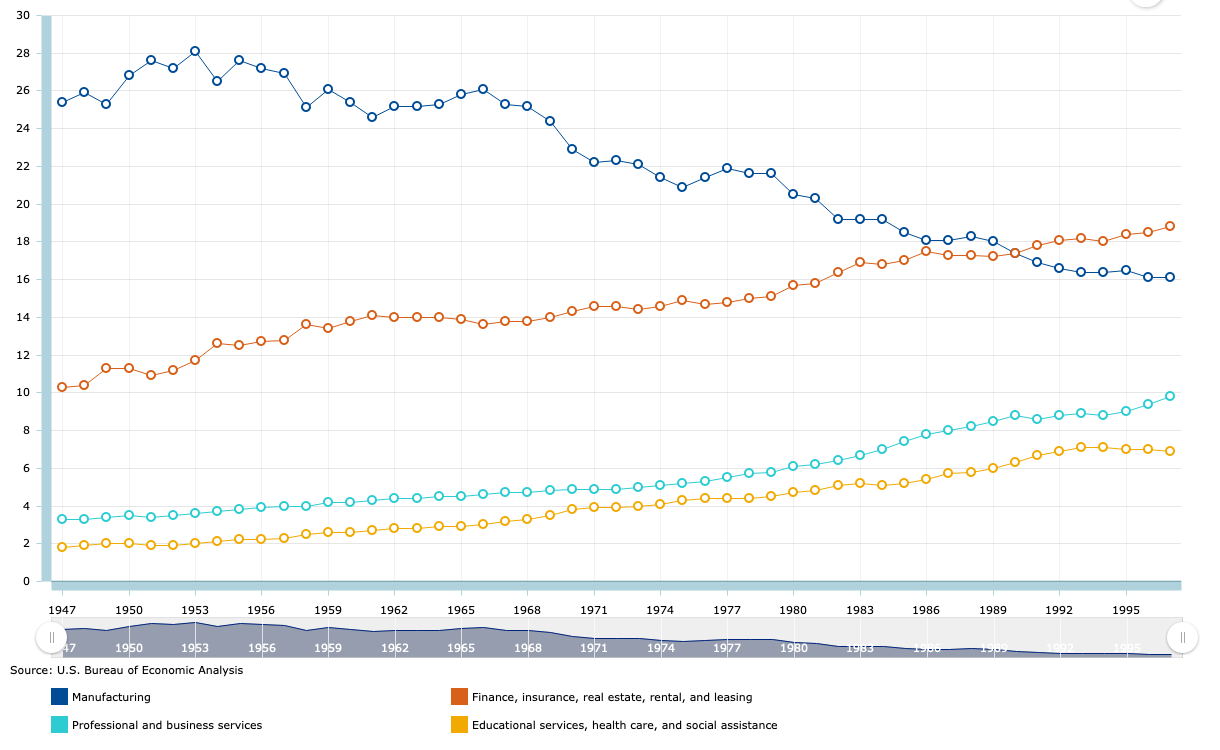

Over a longer timespan, we can zoom in on the relative weight of different major sectors in the US GDP, from 1947-1997.26

Notably, most of what we typically imagine a “service economy” to consist of — accommodation, food services, arts and entertainment — is not pictured here. They are a relatively small percentage of the GDP and do not increase over this period. Retail, a larger percent of GDP (but still too small for this chart), actually declines over this period much like transportation and warehousing. What we observe then is that the “service sector” as traditionally imagined has, for the most part, not experienced any relative growth at all! The one exception is education and health care, which is a natural consequence of the vast expansion of higher-education across the population and increased life-expectancy and the growing array of medical technologies able to treat disease. But even then, that accounts for less than eight percent of the GDP!

Let us now examine the two remaining categories of note, where the remaining bulk of relative growth at the expense of manufacture has developed. The first is professional and business services. Of this, employment is split roughly half between “Administrative and Support and Waste Management and Remediation Services”27 (consisting of “office administration, hiring and placing of personnel, document preparation and similar clerical services, solicitation, collection, security and surveillance services, cleaning, and waste disposal services.”) and “Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services”28 which in turn is dominated by accountants, auditors, lawyers, and management analysts. What these categories have in common is that they are business-to-business services providing specialized “outsourced” support to corporations. The growth of this sector does not necessarily mean e.g. that offices are now being cleaned more than before. It simply reveals that tasks that would have been overhead tasks within large capitalist firms are increasingly subcontracted out to specialized firms, either at the high end (accountants and lawyers) or the low end (cleaners, clerical work, etc.). The subcontracting out of cleaners and the like was specifically conducted as an assault on workers, allowing companies to provide one set of benefits to their “official” workers, and much worse conditions and job security to labor they consider more menial and disposable, segmenting the workforce and attempting to disrupt possible bonds of solidarity.

Finally, there is the largest category: Finance, Insurance and Real Estate. But this cannot be part of the “real economy” at all. As described in Volume III of Capital, it is either “fictitious capital” (either serving a necessary purpose in the circulation of capital, or simply reflecting a speculative investment bubble. More often, it’s a bit of both) or extraction of ground rent. In both these cases, the contribution to the real GDP either is purely on paper, in the form of an asset bubble, or is in fact reflective of parasitism, with the profits accrued to these sectors being taken from the actual value produced elsewhere.

Thus, we see that the apparent decline in the structural prominence of industry and manufacture can be explained by real economic changes. These changes do not illustrate a “post-industrial economy”. Rather, they testify to the increased education and skilling of the workforce, the vast growth of parasitic finance capital as fueled by (among other things) deregulation in the 1980s, and attacks on working class conditions through a pervasive increase in outsourcing.

Formal and Informal Workers in the World Economy

Along with challenging an exclusive focus on the industrial proletariat, McDermott’s article makes a second contribution in arguing for a re-evaluation of informal workers. It argues in particular against the assumption that informal workers “are all self-employed petty producers and vendors” and further against the idea that “those informal workers who are self-employed as petty producers and vendors (i.e. own-account workers) are somehow insulated from, and exterior to, capitalist dynamics and relations, and, therefore, are not (significant) members of the global working class.”

The first claim is uncontestable. Informal workers constitute a significant portion of the working class. Within the U.S., many important organizing drives have taken place among immigrant and undocumented populations, particularly in cases where such workers have not been formally employed (i.e. employed in a way registered with and regulated by the state). Examples include the UFW organizing of the 1960s among California farm workers and the “Justice for Janitors” campaigns of the SEIU in the 1990s. The use of informal day labor is notorious in the construction industry. Beyond that, the moment one begins organizing in the service and retail sector among smaller employers, one immediately encounters questions about all sorts of workers with various “under the table” pay arrangements.

However, the second claim, that “own-account workers” (a category defined by the ILO) are in fact workers, is far more complicated and dubious. McDermott’s claim rests on the idea that such people are not exterior to capitalist dynamics and relations. But in a world capitalist system, virtually nobody is exterior to capitalist dynamics and relations; amongst the most implicated are the capitalist class themselves. Many people that McDermott thus classifies as “members of the working class” are, according to a standard Marxist analysis, members of the petty-bourgeois class. This is again not a value judgment, but a recognition of economic dynamics and material interest.

Small vendors tend towards an individual rather than collective consciousness. They see their success as conditioned by their individual work ethic. They seek to establish themselves as more successful entrepreneurs, able to hire others. Food cart vendors exemplify this class position. If they meet success in their product, they seek to scale upwards and outwards. They can expand the quantity of food prepared and sold or the number of carts, perhaps dreaming one day of a “brick and mortar” location. They will necessarily hire wage labor and workers of their own and act as petty capitalists, increasingly stepping back from day-to-day work to a managerial and supervisory role. Many dream of one day hiring someone even for that and simply living off the profits. For these petty entrepreneurs, advancement in their conditions does not come through improving their conditions at the expense of capitalist profit, but simply in becoming more capitalist-like themselves and partaking in profit-bearing enterprises.

This is not to dismiss such petty-bourgeois layers. They can be a powerful force side by side with workers. But in seeking to organize among them and with them, We cannot be blinded into imagining they are simply workers as we seek to organize among them and with them. Recognizing their class character lets us draw from the rich Marxist tradition of literature on how the proletariat and the petty-bourgeois should relate. In Russia in 1903, for example, Lenin’s “To the Rural Poor” focused on how the petty -bourgeois peasantry of the countryside was not a uniform mass, but itself internally differentiated, between rich, middle, and poor peasants. The last of these had been largely dispossessed, and effectively constituted an agricultural proletariat. The first of these had grown strong enough to be inclined in its sympathies to landlords and capitalists. IAnd in between, a vast layer of middle peasants lived within a nexus of competing interests and impulses. Their, with sympathies couldsympathies that could go either way. Of these, Lenin wrote: “The rich call him to their side: you, too, are a master, a man of property, they say to him, you have nothing to do with the penniless workers. But the workers say: the rich will cheat and fleece you, and there is no other salvation for you but to help us in our fight against all the rich.”29

He went on to argue that the path to winning over this middle layer was not primarily direct ideological struggle, but through building the strength of the alliance between urban and rural workers, which in turn would draw the middle layer behind them. Lenin wrote, “No honeyed words about the advantages of small-scale farming or of co-operatives will enable you to evade these questions. To these questions there can be only one answer: the real ‘co-operation’ that can save the working people is the union of the rural poor with the Social-Democratic workers in the towns to fight the entire bourgeoisie.”30

While the Bolshevik Party was, during the course of the Russian Revolution, able to carry out this program and draw the rural peasantry behind them during the Russian Revolution, it was not so for the Chinese Communists of the 1920s and 19330s; they subordinated themselves to the bourgeois nationalist forces of the KMT, and in 1927, the KMT turned on them, expelling them and then conducting a bloody massacre. With the urban workers routed in the cities, the civil war against the KMT took the form of peasant uprisings throughout the countryside. In the midst of this, Trotsky’s “Peasant War in China and the Proletariat” hailed the success of the peasant armies. Yet it presciently warned: “In the event of further successes—and all of us, of course, passionately desire such successes—the movement will become linked up with the urban and industrial centres and, through that very fact it will come face to face with the working class. What will be the nature of this encounter? Is it certain that its character will be peaceful and friendly?”

Drawing on his experience as commander of the Red Army during the civil war in Russia following the October Revolution, he described the conflicts they encountered at the time as stemming from a common cause:31

The worker approaches questions from the socialist standpoint; the peasant’s viewpoint is petty bourgeois. The worker strives to socialize the property that is taken away from the exploiters; the peasant seeks to divide it up. The worker desires to put palaces and parks to common use; the peasant, insofar as he cannot divide them, inclines to burning the palaces and cutting down the parks. The worker strives to solve problems on a national scale and in accordance with a plan; the peasant, on the other hand, approaches all problems on a local scale and takes a hostile attitude to centralized planning, etc.

Trotsky’s argument was not to dismiss the importance or strength of any group, but to recognize how material circumstances related to interests and consciousness. The conclusions drawn were strategic, based not just on where struggle was occurring, but what direction it was moving in. In so doing, it was important to find not only conjunctural confluences of interest, but also to distinguish fault-lines which would lead to long-term divergences if left unchecked. The state that issued from the victorious 1949 Chinese Revolution was the product of a protracted peasant war in the countryside; however, this government was not one where workers ruled, it was instead one where workers had been politically displaced by the peasant masses and the proletariat was politically expropriated from inception.

Productive and Unproductive Labor, the Reserve Army of Labor, and the Lumpenproletariat

McDermott makes references to some groups being defined with the “usually derogatory term ‘lumpen’”, complains of an “analytically lazy and often ahistorical application” of “the reserve army of labor”, and describes workers who are in public and service sectors as being traditionally recognized as “‘unproductive’ workers (or even lumpenproletariat in the most dogmatic terms).

There is certainly confusion in these usages, but McDermott’s article serves to perpetuate rather than clarify it. It is worth disentangling because some of the concepts at play matter a great deal in how we are to understand the current state of class formation, in its flux and transformation.

Marx’s distinction between productive and unproductive labor has always been fraught in the details, but what is clear is that productive labor is that which adds value to a commodity. The raw inputs to a process of productive labor have less value than the value of the finished product. The difference is in the value contributed by productive labor. Unproductive labor does not transform a product by adding value, but that does not mean that it is in any sense unnecessary labor. Rather, it is necessary for the value of commodities to be realized, or otherwise for society to maintain and reproduce itself. Some such labor, such as advertising, is arguably quite useless to the real needs of society and would be reduced or vastly diminished in a rational (socialist) economy. Other labor, such as inventorying products, managing and planning production and distribution, etc., is socially necessary regardless.

Marx drew the distinction to analyze specifically how value is produced and how capital structures production. Workers who perform labor unproductive of value but socially necessary are paid from the general wage fund and are exploited just as any other worker. Their labor figures into the overall accounting of profit and expenses of their employers, just as any other worker. The distinction between labor productive and unproductive of value is of use in analyzing the cost of circulation and realization in the course of what Marx termed the circuit of commodity capital.32 However, it is not pertinent to analyze who is a worker, who is exploited, or what potential social power any group of workers in particular has. Some public sector workers and service sector workers may indeed be “unproductive” as McDermott suggests, but many are not. There is no reason to suggest that the ratios in the public and service sectors are especially disproportionate. In a sense, teachers simply produce a commodity that is immediately consumed. To the extent a social worker fills out paperwork, this is unproductive (and they will be the first to tell you that!), but to the extent that they actually help the families they are assigned to, then their labor is productive. In fact, the biggest reservoirs of unproductive labor are to be found in the “middle class” occupations of advertising, accounting, finance, and so forth.

Nor would there be any “dogmatically orthodox” reason to consider any such workers lumpenproletariat, a grouping identified by Marx as having a particularly defining characteristic of not working. Nonetheless, the relationship of the unemployed to the workers’ movement as a whole is an important topic with serious strategic implications, only some of which can be touched on here.

In Chapter 25 of Volume 1 of Capital, Marx gives a very rich and extended treatment of an approach to periodic crisis, the tendency of the rate of profit to decline, overproduction, and also, the growth of the “industrial reserve army”.33 First, Marx distinguishes a “relative surplus population” – again, not a derogatory term, but an analytical one. This constitutes the portion of workers able to work, but for whom capitalism cannot provide employment. It is a “relative” surplus because it is only surplus relative to capitalism’s ability to provide employment, not relative to some other notion of the value and dignity of human life, nor to production directed towards the well-being of all.

The relative surplus population cannot be dismissed from Marx’s analysis of capitalism. On the contrary, it plays a central role. Such a population is necessarily generated by capitalism, and necessarily grows over time, as accumulation of capital creates efficiencies which lead to a relative diminution in the need for workers. Even more deviously, the existence of this population serves capital in its war against labor by buffering the demand for labor, thus reducing the ability of workers to bargain for higher wages:

The industrial reserve army, during the periods of stagnation and average prosperity, weighs down the active labour-army; during the periods of over-production and paroxysm, it holds its pretensions in check. Relative surplus population is therefore the pivot upon which the law of demand and supply of labour works. It confines the field of action of this law within the limits absolutely convenient to the activity of exploitation and to the domination of capital.

Moreover, it is the invariable development of this relative surplus population, which, Marx notes, if “tomorrow morning labor were reduced to a generally rational amount” would immediately find productive employment, that constitutes the “General Law of Capitalist Accumulation” which gives Chapter 25 its name.

The law, finally, that always equilibrates the relative surplus population, or industrial reserve army, to the extent and energy of accumulation, this law rivets the labourer to capital more firmly than the wedges of Vulcan did Prometheus to the rock. It establishes an accumulation of misery, corresponding with accumulation of capital. Accumulation of wealth at one pole is, therefore, at the same time accumulation of misery, agony of toil slavery, ignorance, brutality, mental degradation, at the opposite pole, i.e., on the side of the class that produces its own product in the form of capital.

If we were to deny that capitalism produces a relative surplus population, and casts people out of work, by excluding from the industrial reserve army all those who collect cans or sell salvaged goods on streetcorners, then we would be simply blinding ourselves to one of Marx’s central points both in his analysis of capitalism and his denunciation of it – that the accumulation of capital and vast wealth is coupled to the overwork of some while others are thrown from production entirely and into destitution.

Marx’s analysis does not stop short at defining a relative surplus population. He then distinguishes three subcategories: “the floating, the latent, [and] the stagnant.”

The floating surplus corresponds roughly to that measured by the unemployment rate – that portion of the workforce that is simply between jobs, but actively seeking employment. The latent surplus are those who are not workers, but can be drawn into the workforce. In Marx’s time, this was largely the agricultural population of the countryside, “constantly on the point of passing over into an urban or manufacturing proletariat, and on the look-out for circumstances favourable to this transformation.” Similar circumstances exist in many countries of the “periphery” today. In the U.S., this would maybe take the form instead of “downwardly mobile” petty -bourgeois workers in skilled white-collar occupations (often with humanities degrees), who have face the prospect of proletarianization as their occupations collapse and the potential influx of “latent” proletarian labor from abroad.

Finally, there is the third, stagnant, portion of the relative surplus population, which he further subdivides into three categories (and really a fourth). This stagnant portion “dwells in the sphere of pauperism” – those who are not only not working currently, but have not been working, and who do not expect to work. This includes people able to work, but driven out of the labor market semi-permanently through lack of opportunity. Second, “orphans and pauper children,” who, Marx noted, in his time would be themselves speedily and in large numbers enrolled as workers during industrial booms. Finally, there are those too sick, injured, aged, disabled to work. The fourth category is those Marx notes he has otherwise excluded from consideration: the “dangerous classes” of criminal elements, which is termed the lumpenproletariat.

The careful distinctions Marx drew are of help to us today. It is outlandish to call anyone actively working lumpenproletarian, in the formal economy or otherwise. It similarly makes no sense to class nearly any of the unemployed this way. These are workers who happen to be between jobs. But calling one of Tony Soprano’s hitters a worker in the informal economy seems a bit of a stretch. Lumpenproletarians do exist, and they are generated by capitalism. In contrast to those workers who perform unproductive but socially necessary labor, criminals of this sort perform activity that is socially unnecessary, and if anything, stands in the way of the circulation of capital. This is to say they are not simply active workers or unemployed persons who may occasionally shoplift from Target or engage in less than legal transactions to supplement their income. They are people who are, as they say, in the “life of crime,” and a small enough minority of the population that they need not be considered in any of the large-scale trends we are discussing at all.

The Process of Class Cohesion and Formation

The Manifesto describes how “the collisions between individual workmen and individual bourgeois take more and more the character of collisions between two classes.” This process, like all social processes, is not automatic. It takes place through the conscious actions of individuals, who may speed, slow, or shape its outcome. The approach of Lenin and Trotsky was not to simply sort people into classes as a census-taker might. They were looking for ways to generate class solidarity, consciousness, and alignment, and particularly to guide the rural poor to reconceive of themselves as having an essential unity of interests with urban workers.

This class formation which Russia underwent over the course of its rapid industrialization had occurred far earlier in the development of the working class in England. There, the shift from individual production to home-piecework and finally collective waged labor was a drawn out and subtle economic process. In the midst of it, workers may have seen themselves at any moment more as small producers in competition with one another, or more as a group with a common exploiter: the capitalist. Their sense of themselves as a class with unitary interests and the need for joint struggle did not arise in a sudden stroke, nor without human intervention. It was far-sighted leaders and organizers who worked to cohere the class in the course of particular struggles. And the outcomes of those struggles changed material economic circumstances, in the form of common bargaining and united organizations, bringing settlements whose structure further reduced atomization, diminishing competition between workers and establishing terms of united confrontation with employers. This is to say that the course of social struggles shaped the class that emerged – not only ideologically, in its self-recognition, but in the material basis of economic engagement in which that consciousness was rooted.34

The cases of England and Russia are exemplary, but not uncommon. Such processes have occurred time-and-again throughout the development of class struggles – from the IWW’s work in mining and logging communities in the American West35 to the organizing of garment workers in New York and Chicago at the beginning of the 20th century, many of whom were also caught between piecework, small production, and industrial exploitation.36 We even see such a process in the roots of the modern Teamsters, whose strength was born from the drive to organize over-the-road truckers and cohere a master contract across the myriad of small trucking concerns at the time.37 We have more recently witnessed proletarian decomposition in that same industry, borne on the back of deregulation and a newfound rise in owner-operators. Today, in strategic logistical workforces like the ports, truckers often work on an owner-operator basis. Existing unions have by-and-large failed in organizing them away from craft and petty-bourgeois structures towards industrial amalgamation; this is due in part to preferring jurisdictional disputes through existing mechanisms to the substantially more political task of organizing the unorganized.38

To say there is no “pure” proletariat is not merely a statement about consciousness; it is also one about material conditions. In the U.S., workers with stable jobs own houses, or aspire to. Working people with even unstable jobs often have a more traditional one alongside one or another entrepreneurial “side-hustle,” be it catering or bootleg DVDs or even multi-level marketing schemes. “Own-account” workers constitute a census category, not a stable grouping. This category, includes a myriad of occupations and financial arrangements; some are proletarian in all but name, some are closer to small capitalists, and there are many whose loyalty and identification is contingent. Bringing these people to identify with workers and organize with workers is not solved by changing labels, but by advancing proletarian struggles that can transform material conditions – bringing such mixed-workers into associations, transforming those associations into guilds, and developing those guilds into unions.

The problem of drawing people to identify as workers and organize as workers does not apply only in intermediate layers, but even in the most “traditionally understood” industrial working class. When workers do not stand together and fight for common interests, their cohesion and solidarity has a tendency to disintegrate. Unions cannibalize one another, raiding members and shops rather than building solidarity. Labor leaders of different factions vie for office on the basis of ethnic divisions, accusations of corruption, or even by representing different segments of workers as opposed to one another. This fuels cynicism and disintegration among workers. We often speak of employers “third-partying” unions through their anti-union campaigns; the current conservative labor movement will “third-party” itself by presenting itself as serving the workers, rather than being composed of and run by them.

Often lurking behind debates on who constitutes the “working class” in the Marxist sense is a search for a “revolutionary subject” that comes ready-made. A hope that by refining our analysis enough we can stumble across some group of workers who are numerous, powerful, and ready to rumble. If only we could find that one group of workers, somehow uncontacted and uncontaminated and apart from the difficulties in consciousness of all other workers – ourselves, our coworkers, our neighbors and relatives – then just go to them and convince them – well, that could change everything! There is no way around the hard problem of conflicted loyalties, confused consciousness, and disorganization. Creating an organization that can act as a collective organizer is inseparable from the task of constituting the working class as a collective entity.

The job of constituting this self-consciousness is harder today than 50 years ago. The standard analysis of “deindustrialization” is inaccurate in characterizing actual economic transformations, but it seeks to explain an accurate sense of the profound political defeats inflicted on workers, which have atomized them and set back their sense of themselves as a class. It is not that the proletariat has been destroyed as a unit of economic analysis, but it has suffered a profound series of setbacks and defeats to its sense of itself as a class – production has been atomized, unions have lost ground (and those that remained became entrenched and conservative), and until recently, communism was rendered a bugaboo and swear word.

From the standpoint of socialist strategy, it is far more relevant to understand the consciousness of the class than its precise boundaries. The boundaries of the working class as it is reconstituted through waves of struggle (such as the upsurge we are currently undergoing) are not fixed ahead of time – but will be the ones we help it to discover, as we organize. In so doing, we must bear in mind the analysis of Marx and the Bolsheviks. The unique character of the modern proletariat lies not just in its numbers or its economic centrality, but also its collectivity and universality. Today, no less than in the 19th century, it is the task of leftists to not only forge socialist consciousness, but also to forge, cohere, and strengthen the class itself. For Marxists, saying people are workers is not just an act of classification, but a statement of intent.

- Erik Olin Wright, ed. Approaches to Class Analysis (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

- James Burnham, The Managerial Revolution (John Day Co., 1941).

- John Kenneth Galbraith, The Affluent Society (Houghton Mifflin, 1958).

- Wilbur Hugh Ferry, “The Triple Revolution,” Liberation (April 1964).

- Barbara and John Ehrenreich, “The Professional Managerial Class” in P. Walker, P. Ed., Between Labor and Capital (South End Press, 1979).

- inthesetimes.com/article/unions-labor-strikes-starbucks-amazon-higher-ed/

- againstthecurrent.org/atc226/why-the-rush-to-settle/

- www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/ups-workers-approve-5-year-contract-agreement-to-end-negotiations/

- finance.yahoo.com/quote/SBUX/financials/

- https://www.wgrz.com/article/news/verify/verify-ship-stuck-in-suez-canal-cost-economy-400m-an-hour/507-205b5e13-8107-4a0f-83df-266c96230f10

- See chapter 20 in particular: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1885-c2/ch20_01.htm/

- fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MANEMP

- www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1899/dcr8vii/vii8v.htm#bkV03P501F02/

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/plekhanov/1889/07/speech.html

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/plekhanov/1883/struggle/chap2.htm

- www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch01.htm/

- data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.IND.MANF.CD

- https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/N400RC1Q027SBEA

- https://www.ft.com/content/74f7e284-c047-4cc4-9b7a-408d40611bfa

- Thomas Y. Owusu, “Economic Transition in the City of Paterson, New Jersey (America’s First Planned Industrial City): Causes, Impacts, and Urban Policy Implications”, Urban Studies Research, vol. 2014(3), 1-9.

- Lars G. Sandberg, Lancashire in Decline: A Study in Entrepreneurship, Technology, and International Trade (The Ohio State University Press, 1974).

- Norman Gilbert, Roger Burrows, and Anna Pollert, ed. Fordism and Flexibility (Mac Millan, 1992).

- Thomas J. Sugrue, The Oorigins of the Uurban Ccrisis: Race and Iinequality in Ppostwar Ddetroit-updated edition. , 2nd ed. (Princeton University Press, 2014).

- Pete Dreier, John Mollenkopf, and Todd Swanstrom, Place Matters: Metropolitics for the Twenty-First Century, Revised. (University Press of Kansas, 2014).

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.IND.MANF.ZS

- https://www.bea.gov/itable/gdp-by-industry. The reason we pick our cutoff at 1997 is that industrial classifications change after 1997, which means the data series before and after are disjointed.

- https://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iag56.htm

- https://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iag56.htm

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1903/rp/3.htm

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1903/rp/4.htm

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1932/09/china.htm

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1885-c2/ch06.htm

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch25.htm#S4

- For a sketch of some of this, see https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch21.htm

- William D. Haywood, The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood (International Publishers, 1929).

- Steven Fraser, Labor Will Rule: Sidney Hillman and the Rise of American Labor (Cornell University Press, 1993).

- Ralph and Estelle James. “Hoffa’s Impact on Teamster Wages.” Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society 4, no. 1 (1964): 60-76.

- See:

https://www.labornotes.org/2021/12/its-awfully-convenient-shippers-longshore-workers-get-blamed-delays-contract-fight-looms

https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2019-11-07/port-automation-dockworkers-vs-truckers

https://jacobin.com/2022/02/west-coast-port-truckers-xpo-logistics-nlrb-union-election-teamsters