Debates about historical events are proxies for struggles over how to run the world, how to change the world, and whether the world should even be changed. This holds true most of all for revolutions, the French Revolution being a prime exemplar. When we look at the history of the French Revolution, we see not merely a disputation over facts but a debate about their interpretation, one which is thoroughly political, not merely academic. This is a dispute that is ideologically loaded and related to greater trends in political (and therefore class) conflict. The debates about the meaning of the French Revolution do not stand outside of history; they are expressions of greater conflicts - republicanism against monarchism, socialism and communism against capitalism, and the true meaning of democracy. We can never assume that when scholars discuss the French Revolution they are engaged in an ideologically neutral exercise of fact-finding; that work is long done. When one portrays the French Revolution as an outpouring of chaotic mob violence or as the product of greater historical process of class struggle they are elaborating a political agenda, consciously or unconsciously. History is a partisan struggle, the construction of narratives to frame significant events is a terrain of this struggle.

Beginning the Historiographical Battle

The historiography of the French Revolution goes back to before the closing of the revolutionary period. Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France was a response to revolutionary events that was conservative and skeptical, mostly condemning the revolution as a pointless excess. On the other side of this political divide, between monarchism and revolutionary republicanism, was Thomas Paine's The Rights Of Man, which celebrated the democratic and republican aims of the revolution. Burke would inspire the likes of Catholic reactionary Joseph De Maistre, who saw the revolution as the bloody and chaotic result of Enlightenment ideology undermining the divine right of Kings. Following De Maistre was another Catholic reactionary, Augustin Barruel, a Jesuit priest who promoted the idea of the revolution as a plot of the Freemasons and Illuminati and invented the modern conspiracy theory. Throughout the nineteenth century historians such as Michelet[1], Guizot[2] and Thiers[3] would follow while building upon the tradition of Paine that saw the revolution as a triumph of the bourgeoisie (or third estate) and their values of democratic-republicanism. François Aulard, the first professional historian of the revolution, would solidify this interpretation with his multi-volume works written in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The notion that the class which benefited most from the revolution was a progressive bourgeoisie that represented Enlightenment values was at the core of these republican historians and served as a predecessor to the Marxist argument that the revolution was a bourgeois revolution. It is this claim that would be the centerpiece of debates in the future historiography.

We can see from the aforementioned examples that a political battle was already being fought within the historiography of the French Revolution. On one end were those who sought to defend the revolution as open new vistas of human potential, in turn espousing Enlightenment values of progress and humanism where reason would lead the way to expand freedom and liberty. On the other end were a decadent ruling aristocracy and the Catholic clergy, who saw the revolution as at best an unfortunate excess inspired by the flaws of Enlightenment ideology, at worst a Satanic punishment for the sins of man. These conflicts in the writing of history were related to a greater conflict in the nineteenth century between the forces of republicanism and the forces of monarchism. As we shall see this historiographical divide was a predecessor to the politicized historiographical debates of the twentieth century between the Marxist historians and the revisionist historians, defending the necessity of socialist revolution and the legitimacy of the capitalist order respectively.[4]

Marxism Enters the Stage

The development of the first mass socialist parties and the rise of a Marxist intellectual culture associated with these parties created a whole new school of thought on the French Revolution. The thought of Karl Marx was central to these parties, and would, therefore, be central to a new generation of writers and historians who apply his theories to understanding the French Revolution. Marx’s own views on the French Revolution were a synthesis of the critiques of the limits of the revolution made by early Communists such as Babeuf, Buonarroti and Moses Hess as well as the aforementioned Republican historians such as Guizot and Thiers.[5] However, the most important contribution from Marx towards the historiography in question was his theory of historical materialism, which aimed to understand social development as a dynamic process fueled by class struggle. This theoretical framework would have more influence on future historians of the revolution than any of his scattered comments on the event itself. Most importantly, Marx’s thought was energized by a revolutionary politics that aimed to continue the work of the French Revolution, while also transcending it. His understanding of the revolution as a bourgeois revolution was a greater statement about revolutions and class struggle as the locomotive of history, not a mere scholarly claim. To quote Michael Löwy:

Naturally, this analysis of the—ultimately—bourgeois character of the French Revolution was not an exercise in academic historiography: it had a precise political objective. In demystifying 1789, its aim was to show the necessity of a new revolution, the social revolution—the one Marx spoke of in 1844 as ‘human emancipation’ (by contrast with merely political emancipation) and in 1846 as the Communist revolution.[6]

With the intellectual breakthrough of Karl Marx, a new development in the historiography of the French Revolution would begin. A new school was in formation, one which would be known as the social interpretation. A groundbreaking work in the formation of this school was A Socialist History of the French Revolution by Jean Jaurès, one of the most prominent leaders of French socialism. Jaurès’ work was not only a work of scholarship but also a politically motivated work, one that aimed to ”recount the events that occurred between 1789 and the end of the nineteenth century from the socialist point of view for the benefit of the common people, workers, and peasants.”[7] Jaurès oriented his own politics around the heritage of the French Revolution, aiming to combine its republican nationalism with the socialist ideal. He framed his politics around the French Revolution and told socialists that they were the true inheritors of its legacy.

Jaurès’ approach to the revolution was that it was an “immense and admirably fertile event” that “signified the political advent of the bourgeois class” and “gradually set the scene for a new social crisis, a new and more profound revolution by which the proletariat would seize power in order to transform property and morality.”[6] Robespierre and the Jacobins were heroes, Jaurès siding with them even when they clashed with the plebian classes because of the historical necessity of the bourgeoisie’s triumph. In some senses Jaurès oversimplified events: the revolution unfolded smoothly as if the sole cause was the economic development of the bourgeoisie. Regardless of weaknesses, his work was groundbreaking, providing the first comprehensive history of the revolution within a Marxist framework.

Jaurès used the legacy of the French Revolution to defend the politics of the Second International. Albert Mathiez, a French author writing in the years following the Russian Revolution, would turn to this legacy to defend Bolshevism and claim Lenin’s party as the inheritors of the Jacobin project. Lenin himself appealed to the legacy of the Jacobins, saying

Bourgeois historians see Jacobinism as a fall ("to stoop"). Proletarian historians see Jacobinism as one of the highest peaks in the emancipation struggle of an oppressed class. The Jacobins gave France the best models of a democratic revolution and of resistance to a coalition of monarchs against a republic...“Jacobinism” in Europe or on the boundary line between Europe and Asia in the twentieth century would be the rule of the revolutionary class, of the proletariat, which, supported by the peasant poor and taking advantage of the existing material basis for advancing to socialism, could not only provide all the great, ineradicable, unforgettable things provided by the Jacobins in the eighteenth century, but bring about a lasting world-wide victory for the working people.[8]

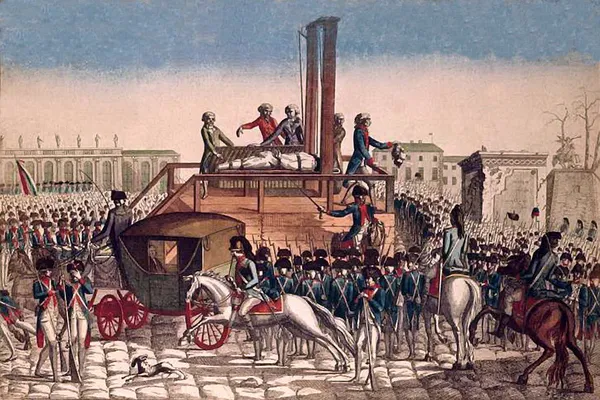

While Jaurès saw the revolution as unfolding smoothly according to economic causes, Mathiez emphasized violence and sudden ruptural changes. One can see these differences as an expression of political divergences, Jaurès having a more reformist temperament and Mathiez being more of a militant insurrectionary inspired by the Bolsheviks. A key part of Mathiez’s writings on the revolution was the defence of the Jacobins’ use of terror, which was a rational response to issues forced upon the Jacobins by the logic of revolution. The Committee of Public Safety, said Mathiez, was “urged on by irresistible necessities...In fact these men had the dictatorship forced upon them. They neither desired or foresaw it.”[9] Mathiez would directly compare the dictatorships of the Bolsheviks with the Jacobins, stating

The origin and the strength of both dictatorships was drawn from the population of the cities, and in particular the capital. The Montagnard’ fortress was in Paris in the popular sections composed of artisans; the Bolshevists recruit their Red Guard from among the workers in the factories of Petrograd.[10]

In defending the Reign of Terror as something imposed by the necessity of revolution, as well as defending the French Revolution as a bourgeois revolution in line with Marx, Mathiez was, in turn, defending the tactics used by Bolshevism. He was using history as a partisan in an ideological struggle, defending the necessity of revolution for social progress with all the violent difficulties that came with it. Along with Jaurès, Mathiez was helping to form a historical school that was not only based on defending the cause of the proletariat but also was oriented around a Marxist theory of history which saw the revolution as part of a grander historical scheme centered around class struggle and changing modes of production. In doing so they set the stage for the social interpretation of the French Revolution, the interpretation that would come to be the historical orthodoxy despite its radical origins.

The Social Interpretation

The actual break between the social interpretation and its earlier Marxist predecessors is ultimately not an immense one. Jaurès and Mathiez created the basic groundwork and later historians would build upon it to form the official canon that became hegemonic in the French academy. The primary difference was one of depth and academic acclaim. It was Georges Lefebvre who would take the earlier Marxist historians and develop their work into what is known as the social interpretation. Lefebvre held a position of influence in the academy, having been named the Chair of the History of the French Revolution at the Sorbonne. Using this position of influence he was able to cement into historical orthodoxy an essential Marxist interpretation which focused on history as a process of class struggle. Yet from reading Lefebvre one gets a sense that he aimed to distance his approach from Marxism to gain acceptability in the halls of academia. He avoided its precise jargon (words such as “mode of production” or “proletariat”) while maintaining its core principles in his analysis. One of these core principles was the concept of bourgeois revolution, centered in the interpretation of Marx himself and the earlier Marxist historians. However, Lefebvre would avoid making his allegiance to Marxism stand at the forefront of his work. While Lefebre did not represent much of a break from the earlier Marxist historians, his work was able to appeal to historians who would have otherwise dismissed Marxism. This was not because of the lack of Marxist jargon in his work. Lefebvre’s innovations mostly came in his ability to pioneer what is today known as “history from below”, an approach to history that focused on the daily life and popular attitudes of everyday people.

Lefebvre’s first work was the 1924 monograph The Northern Peasants During the French Revolution, possibly the first account of the French Revolution that focused specifically on the peasantry. In 1932 came his work The Great Fear of 1789, focusing on the violent hysteria that swept the French countryside at the beginning of the revolution. While earlier Marxist approaches focused on the importance of class, Lefebvre put a magnifying glass to the actual activity of these classes on the ground. He also aimed to elaborate a more comprehensive account of all the different classes in the revolution, not simply the bourgeoisie. His 1939 book The Coming of the French Revolution presented the revolution as more than a mere political revolution, but as a social revolution having four separate components: the aristocratic revolution, the bourgeois revolution, the popular revolution, and the peasant revolution. Lefebvre’s account still centered a rising bourgeoisie and an aristocracy in decline, the bourgeoisie having gradually developed economic power in the interstices of a society based primarily on landed property owned by the nobility. Yet the key to the power of this rising bourgeoisie was the insurgent plebian classes. Lefebvre’s focus on the peasantry showed the crucial role they played in challenging absolutism, documenting the war they waged on a system of seigneurial dues that formed the backbone of the old feudal order. In Lefebvre's social interpretation, class struggle is a historical category of analysis that made the separate events of the revolution flow into a coherent narrative which could explain its deeper objective causes as well as the historical significance of its outcome, which was not a mere political regime change but social and economic in scope.[11] In the last instance, the cause of the revolution was found in greater historical forces that extended beyond the control of its participants. Despite this source of causality in deeper material processes, Lefebvre’s writing gave life to the actions of the everyday people who made revolution. His narrative was not a mechanical and lifeless movement of expanding productive forces necessitating society to meet the needs of development. Instead, Lefebvre illustrated the movement of impersonal historical forces with the habits and consciousness of peasants, artisans, and workers as they struggled against a system of privilege and exploitation.

Albert Soboul's work would continue the social interpretation pioneered by Lefebvre, expanding Lefebvre’s studies of popular movements both in the city and countryside. His contributions are well represented by the 1965 book A Short History of the French Revolution. Unlike Lefebvre, Soboul used explicitly Marxist terminology (mode of production, relations of production, proletariat, ect), working more directly in continuity with Jaurès and Mathiez.[12] At the core of his analysis was the complexity of interactions between classes and political groups. Radical democratic aspects of the revolution meant that the interventions of the exploited classes could shape events in ways that could be to the benefit or detriment of the bourgeoisie and even the development of capitalism. According to Soboul, it was the masses of peasants, petty producers, artisans, and other urban workers rather than the bourgeoisie that would be the real social force that drove the revolution forward and “dealt the gravest blows to the old order of society”.[13] While this interpretation was not original after the work of Lefebvre, Soboul wrote about the revolution within an explicitly Marxist framework. Where Lefebvre's studies focused on the peasantry, Soboul would give a similar treatment to the Sans-Culottes, who would stand at the center of his 1968 work titled after these militant urban workers.[14] Yet Soboul also reaffirmed that the revolution was a product of objective historical forces that were beyond the control of individual actors.

Central to the framework of the social interpretation is the theory of bourgeois revolution. This theory holds that the transition from the feudal to the capitalist mode of production was accompanied by revolutions in which the bourgeoisie would seize political power after gradually developing an economic base within the confines of feudal society. In Lefebvre's account, the revolution was one of “established harmony between fact and law,” with the bourgeoisie overthrowing the absolutist state obstructing their full ascendence as a class and hence the flowering of capitalist development.[15] For Soboul, the roots of the revolution go back as far as the tenth century with the revival of commerce and handicraft production, forms of wealth that were personal and movable. The bourgeoisie gradually developed greater amounts of power within the confines of the feudal order, the development of colonial empires and royal finance contributing to their rise. By the eighteenth century, the bourgeoisie is presented as having a leading role not only in commerce, industry, and finance but the administration of the state as well. Yet to fully ascend to power, the remnants of feudalism and the absolutist state that stood in the way of this rising bourgeoisie would have to be overthrown through revolution.[16] Soboul's interpretation is almost identical to how Marx describes the bourgeois revolution in the Communist Manifesto:

We see then: the means of production and of exchange, on whose foundation the bourgeoisie built itself up, were generated in feudal society. At a certain stage in the development of these means of production and of exchange, the conditions under which feudal society produced and exchanged, the feudal organization of agriculture and manufacturing industry, in one word, the feudal relations of property became no longer compatible with the already developed productive forces; they became so many fetters. They had to be burst asunder; they were burst asunder.[17]

Within the social interpretation of the revolution, there is a sense that the revolution was in a way inevitable, a product of the unfolding of greater impersonal historical forces. This is not to say that Lefebvre and Soboul gave no sense of agency to historical actors. Their work greatly emphasized the role that the popular classes played in moving the revolution forward, often against the will of an anxious bourgeoisie. Yet at the core of this interpretation is the notion that historical events have causality in broader socio-economic factors outside the control of individuals. It is an interpretation that fits within a greater theoretical schema where history is a sequence of modes of production, with transitions between them marked by decisive class struggles, struggles in turn conditioned by the development of productive forces. History has a greater logic to it and is not merely a random sequence of events with no continuity. Nor is it without any contingency. Yet contingency is always limited: human actors make decisions within the limits of events and economic forces beyond their own control. And even these decisions are not made without conditioning from that which came before. Hungarian Marxist György Lukács described this dialectic of structure and contingency in Marxism, where history

is no longer an enigmatic flux to which men and things are subjected. It is no longer a thing to be explained by the intervention of transcendental powers or made meaningful by reference to transcendental values. History is, on the one hand, the product (albeit the unconscious one) of man’s own activity, on the other hand it is the succession of those processes in which the forms taken by this activity and the relation of man to himself (to nature, to other men) are overthrown.[18]

The promise provided by such a theory of history is that by understanding the broader socio-economic conditions that drive history we can then collectively act to change history to better the condition of humanity, in the same way a scientist develops their understanding of natural laws through experimentation and uses this understanding to invent new techniques and technologies to transform nature to meet our needs. The understanding of history utilized by the social historians was not simply an analytical tool but promised to humanity the potential for a better future. Events such as the French Revolution signaled the possibility of building a new society informed by a scientific yet partisan understanding of history.

First Wave of Revisionism

French historians like Lefebvre and Soboul were able to establish the hegemony of the Marxist social interpretation in the academy in a world where the Cold War raged between the Eastern Bloc and NATO. Alongside this military struggle between global camps was an ideological struggle in the academy. Hence this period was one of intellectual works like Karl Popper’s The Open Society and Its Enemies, which linked the totalizing theory of history espoused by Marxists with totalitarian politics. To disprove Marxism was to weaken the intellectual credentials of Communism and weaken its hold amongst intellectuals. To dethrone the social interpretation from hegemony in the academy was, therefore, part of this ideological struggle. It is in this context that we must understand the attacks on the social interpretation of the French Revolution.

The social interpretation would first be challenged by Anglo-American historian Alfred Cobban. Cobban's book The Social Interpretation of the French Revolution (1964) is primarily an attack on the Marxist narrative of the revolution rather than a historical work that breaks any ground in research. His book was a rupture in the historiography of the revolution, breaking ground for what would be known as revisionism. Revisionism would eventually take the social interpretation's place as the prevailing orthodoxy, but first, it would have to demolish the entire foundation that the social interpretation sat upon. This meant attacking the theoretical foundations of the social interpretation: Marxism. For Cobban, Marxism is essentially a religious ideology, because it aims to provide purpose and meaning to human existence. Yet he goes further than rejecting only Marxism, arguing that any kind of sociological theory cannot be mixed with history without providing results that are biased in favor of the given theory. In Cobban's view, Marxism essentially blinded historians like Lefebvre and Soboul from the facts in front of their own eyes by forcing them into the confines of a particular sociological theory.[19] This is similar to Karl Popper’s critique of Marxism as a totalizing worldview that forces facts into a grand historical schema instead of emphasizing skepticism and empiricism. Rather than understanding the French Revolution as an expression of broader historical patterns, Cobban embraced narrow Anglo-Saxon empiricism where the facts essentially spoke for themselves. By looking at the surface appearance of events without connecting them to the broader movement of history Cobban hoped to deal a major blow to the dominant Marxist-influenced interpretations.

The theory of bourgeois revolution was the main target of Cobban's attack. As noted earlier, the theory of bourgeois revolution placed the French Revolution in the context of the transition from feudalism to capitalism, with the revolution as a breaking point in that transition in which the bourgeoise established political dominance and destroyed the absolutist state that was a barrier to capitalist development. Cobban would take the opposite approach, claiming that the revolution was in fact against capitalism and ultimately blocked its development. In this interpretation, the mass revolts of the revolution were primarily against the coming of a newer capitalist order, rather than a revolt against the remnants of feudalism. There was instead a step backward rather than a step forward, with France still a primarily agrarian society after the revolution.[20] One of the ways he makes this argument is by ironically drawing from Lefebvre's own work, particularly his Études Orléanaises study. Using this study, Cobban would argue that the majority of grievances recorded were complaints aimed at the growing commercialization of the countryside rather than the old feudal order. Cited examples showed hatred of large farmers, peasants incapable of attaining ownership of plots having to sell themselves into wage-servitude, and resentment towards financiers.[21] By drawing from Lefebvre's work, Cobban aims to make a specific point: that it was not the facts themselves that Lefebvre got wrong, but that his adherence to the Marxist theory of bourgeois revolution caused him to force the facts into a theoretical schema that contradicted them. Another important argument found in The Social Interpretation of the French Revolution was that the revolution was not itself led by a bourgeoisie which engaged in either commercial wealth or employing waged labor but was rather composed mostly of professionals. Cobban used this to argue that class categories were simply not applicable to the revolution, as all the different groups were purely political and not connected to definable class interests.[22]

Cobban would also argue that whatever type of society existed in ancien régime France could not be described as feudalism. While not putting forward an alternative of how to categorize the social formation in France at the time, Cobban makes the point that seigniorial rights were alienable and were able to come into the possession of non-noble hands. Hence ownership of land and the ability to extract seigniorial dues was dissociated from the status of nobility.[23] Colin Lucas' article Nobles, Bourgeois and the Origins of the French Revolution (1973) would add to the arguments accumulating against the social interpretation, claiming that there was, in fact, no real difference between bourgeoisie and nobility in late eighteenth-century France. Instead, the two essentially formed a homogenous ruling class. In Lucas' view, the bourgeoisie could not even be differentiated from the nobility by their investment patterns, which were primarily motivated by social status rather than the profit motive.[24] For the historian William Doyle, who contributed to the revisionist interpretations with his 1980 book Origins of the French Revolution, the revisionist school had changed the parameters of the discussion, but it was still unclear how and why the revolution came about.[25] What united the Anglo-American revisionist historians was primarily a negation of the existing orthodox historiography, rather than any positive alternative theory that sought to explain the objective causes of revolutionary events. Through a methodology of positivism that was in line with other Cold War attacks on Marxism, the beginnings of a revisionist school were formed.

Furet and the New Revisionist Orthodoxy

François Furet would bring revisionism to Paris itself to do battle with the adherents of the still dominant social interpretation. The work of Furet coincided with a greater trend of anti-communism in the French intelligentsia, coinciding with the New Philosophers like Bernard-Henri Lévy. Like many of the New Philosophers, Furet was an ex-Communist who made no secret of his distaste for Marxism. His attacks on the social interpretation of the French Revolution were politically charged and portrayed the revolution as the beginning of ‘totalitarian’ regimes like Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany, a sort of historical complement to philosophical arguments made by the New Philosophers. This rise of intellectual anti-communism coincided with the decline of the USSR as well as revelations of the horrors of Stalinism from Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago. The general mood of this intellectual conservatism can be summarized by Bernard-Henri Lévy’s statement that “We never will again remake the world, but at least we can stay on guard to see that it is not unmade.”[26] Before Francis Fukuyama proclaimed the end of history, Parisian historians and philosophers were anxious to see that such a situation came about. Such developments would lead Perry Anderson to proclaim Paris as the “Capital of European Reaction.”[27]

It was in this intellectual climate where Furet would negate the dominance of the social interpretation to create a new revisionist doctrine that would stand as the new prevailing orthodoxy, asserting that the revolution was not social and economic but purely political. In his book Interpreting the French Revolution Furet argued for placing an emphasis on subjectivity and ideology as opposed to objective social forces to explain the flow of revolutionary events. The degeneration of Bolshevism for Furet meant that a fresh perspective could be developed on the history of the revolution, where it was to be seen “not in terms of causes and consequence” but rather as the invention of a “new political discourse”. Rather than seeing history as a chain of cause and effect with events as a consequence of those prior, Furet saw history as essentially random, only given meaning by discourse.[28] Furthermore, history was not a process based on an inevitable process of linear progress. In fact, it made no sense to talk of progress at all, only successive forms of domination and irregular explosions of rebellion. In this sense, Furet shared commonalities with another contemporary French philosopher, Michel Foucault.

For inspiration Furet would look towards Alexis de Tocqueville and Augustin Cochin, constructing a historiographical tradition in opposition to that of the social historians. From Tocqueville, Furet took the idea that there was a continuity between the centralized absolutist state structure and the state that resulted from the revolution; the revolution was essentially an expression of a process of state centralization. This idea of continuity was seen as an antidote to the idea that the revolution was a radical break from the feudal to capitalist era, with the revolutionaries believing themselves to be ushering in an era of bourgeois liberty and economic progress. Furet also used Tocqueville to argue that proponents of the social interpretation and the theory of bourgeois revolution made the mistake of taking revolutionary leaders at their word, claiming there was a discrepancy between their objective historical role and their subjective perception of it.[29]

While Tocqueville stressed continuity, Augustin Cochin emphasized what Furet would call “the explosive character of the event” that was fueled by the internal dynamic of the revolutionary movement.[30] Cochin was a Catholic traditionalist who wrote in the late nineteenth century and detested Jacobinism but obsessively sought to understand it. He interpreted it as a result of a growing “philosophical society” which came to political power to replace a collapsing system of corporate bodies. While the ancien régime state was based on corporate bodies which expressed particular interest groups, the “philosophical society” which came into power wished to create an order based on the general will of all individuals in society. These atomized individuals could form no general will according to Cochin, so the result was a centralization of power into the hands of the “philosophical society” which led a dictatorship in the name of a fictitious “people”.[31] Furet takes from Cochin a focus on revolutionary ideology. The revolution ultimately formed an "ideocracy", which in attempting to legitimate a new social order based on the sovereignty of the nation had to “compose a new society by excisions and exclusions...to designate and personalize the powers of evil”.[32]

From these authors, Furet created a synthesis that can be seen constituting the new revisionist orthodoxy. Whereas the Marxist-inspired social interpretation would focus on the objective social dynamics of class struggle that fueled the revolution, for Furet and many historians after him the subjective ideological discourse of revolutionaries was the main factor conditioning the outcome of events. A continuous process of state centralization that began with the ancien régime gave unprecedented state power to a small group of people, but there was also a radical break from the past in terms of political ideology. The socio-economic causes were of little importance for Furet, as the revolution was a purely political event. To compare schools of historiography, the social historian Soboul viewed the Reign of Terror as a product of external and internal pressures of counter-revolution and the class struggles of the Sans-Culottes against grain speculation. Furet, on the other hand, argued that the terror flowed from the very political discourse of the revolution itself, which aimed to construct a “people's will” through a unity based on the violent exclusion of the nobility. Furet's ideas not only fell in line with a general pessimism about popular social change but also a general change in prevailing historical methodology with the rise of the “cultural turn” and post-structuralism.

Under the guise of attacking teleology in Marxism, Furet instead created a new type of determinism, one based on the predominance of ideas rather than economics. If necessity and contingency exist as a dialectic for Marxist theory, for Furet the two exist in a crude opposition, with contingency being absolute. Rather than class struggle structured by relations and forces of production, the revolution flowed according to a linguistic discourse. Furet saw events like the storming of the Bastille and the Reign of Terror as random acts of spontaneity with no real basis in economic forces. Rather than an objective social force that structured history, class struggle was merely a linguistic discourse of revolutionaries applied to events that could take on a life of its own. By emphasizing discourse as a determinant, Furet was taking aim at philosophers who believed they could change the world by blaming their ideas on the violence of the revolution. And by emphasizing continuity with the old regime and dispelling the notion of bourgeois revolution, Furet was proclaiming that all of the violence of the revolution was unnecessary for the development of modernity. This is a philosophy of history devoid of possibility, which in the name of contingency against crude determinism actually consigns humanity to quietism, condemning any possibility of consciously understanding history and changing it for the better.

Furet set the stage for a new orthodoxy to replace the old ways of the social interpretation. This was one that focused on culture rather than economics and class, avoiding any kind of teleology in favor of focusing on how people interpreted events. The “cultural turn” in history became the new norm and Marxism was more and more ‘discredited’ as the Soviet Union collapsed. A paradigm shift had occurred in history, but it was a kind of paradigm shift that would deny itself as progressive because it denies the notion of progress as too teleological. Authors focused on subjective public imagination instead of looking at any broader framework of determinism and causality. An example is author Lynn Hunt, whose Family Romance of the French Revolution utilized the work of Freud to look at how revolutionary writers visualized the absolutist order in terms of patriarchal authority, using familial metaphors to comprehend the revolt against the ancien régime as a revolt against the father.[33] Another author who exemplified the cultural turn was Joan Landes, author of Visualizing the Nation. Landes focused on material culture to examine how gendered representations of bodies were used in popular artwork to link individuals to new identities of citizen and nation, with gendered imagery being used in a negative sense to delegitimize monarchy and define the enemy, as well as in a positive sense to define national values such as liberty, equality, nature, and truth. By personalizing the nation through gendered imagery, popular arts were able to create an emotional attachment to an abstract national identity.[34] Furet’s focus on discourse and repudiation of objective economic causality opened the door for historians to focus instead on identity formation, subjectivity, and culture. There is no doubt interesting work done in this new paradigm. Yet something was lost in the desire to break down the old ways of social history: a sense that the revolution had a greater meaning than those subjectively given to it in the process of history and the struggle for human freedom.

Responding to Revisionism

A full and sufficient response to revisionism is outside the bounds of this essay and would take up a project of wider scope. Yet to not address some of the arguments of the revisionists directly would be a simple appeal to negative ideological implications. Therefore in this section, a basic defense of the social history of the French Revolution will be asserted. This does not mean undertaking a defense of Lebevre’s and Soboul’s exact understanding of the French Revolution as a bourgeois revolution—it is unlikely that after decades of historical debate and inquiry, their interpretations wouldn’t need to be updated and refined. Instead, what is needed to adequately address the claims of revisionism is a defense of the social interpretation’s general understanding of the revolution as a class struggle, rooted in the class structure of French society, and also the category of bourgeois revolution and the applicability of this category to the French Revolution. To begin addressing these questions, we will need to look at the system of French absolutism and its class contradictions.

The developmental path of French absolutism must be understood in comparison with England. In England, the crisis of feudalism in the fourteenth century led to the development of a middle peasantry who began to engage in small-scale capitalist farming. In response, enterprising landlords began a process of enclosure on common lands and took up large-scale capitalist farming, with peasants forced to either sell their labor or join this new class of agrarian capitalists.[35] By the seventeenth century, capitalism was growing in the interstices of English society and the English revolution created a state fit for the rule of this capitalist class. By the end of the eighteenth century, England dominated Europe and set the pace of international competition. This process very much followed the ideal type of a bourgeois revolution, where a capitalist class grew inside a feudal framework and waged a revolutionary struggle to bring the state into harmony with the economy.

France saw a divergent path of development. At the beginning of the fifteenth century, peasant communities were able to empower themselves to secure claims over common lands and heritability rights over tenures, enlarging their holdings by marketing surpluses. But just as this middle peasant class began to develop, they were squeezed out of existence by rising rents from landlords, who were slowly becoming impoverished and reasserted their seigneurial rights.[36] While the French peasantry, unlike the English, were able to hold onto their traditional land rights, this meant they were in a position where landlords could use rent-squeezing to extract surplus. As a result, there was little incentive for both peasants and landlords to invest in improvements and engage in capitalist farming like they did in England. A peasantry now being squeezed of surplus revolted—for example, the Croquants rebellion in the late sixteenth/early seventeenth century, in which peasants appealed to the king to protect them from the unhindered exploitation of landlords.[37]

It was from this dynamic of peasants appealing to the king for protection from seigneurial exploitation that the absolutist state developed. Preferring “royal authority to social anarchy”[38] meant that lords were willing to tolerate the rise of the Bourbon monarchy as a lesser evil to outright destruction of the feudal order. Absolutism rose as a centralizing institution, providing peasants with a barrier to the harshest possible exploitation from local lords. Yet it also maintained the system of tributary domination, revamping it with a more consolidated and centralized state apparatus.[39] The Crown needed to be able to tax the peasantry for income and therefore saw it in its interest to protect peasant property. Yet to fund this state apparatus it was necessary to tax the peasantry alongside the rents they paid to the nobility. To keep the nobility satisfied, the crown allowed a portion of the tax extracted to be shared with them through the selling of offices, which developed a massive bureaucracy to maintain their loyalty. While royal officials would often side with peasants in disputes, they nonetheless placed a burden upon the peasantry. Absolutism, regardless of its origins as a protector of the peasant, pushed the peasant down into poverty through taxation, preventing the emergence of a middle peasantry and therefore the development of endogenous capitalism.[40]

From this portrayal of absolutist France, we can see that the critics of the social interpretation had a point: that the notion of an endogenous capitalist class developing within the feudal order, attaining class consciousness as a bourgeoisie, and throwing off the shackles of feudalism is not accurate. Because of the lack of a dynamic of class differentiation in the countryside, a bourgeois class did not form in France that was capable of uniting and leading a revolution according to its own class interests. Yet this should only discredit the notion of bourgeois revolution if we accept the most simplistic understanding of the concept, where a fully conscious bourgeoisie makes revolution and establishes capitalism, in a smooth and linear process. But what if we understand bourgeois revolution not just as an event, but also as a longer uneven process in history, one which contains simultaneous progress and setbacks?

Regarding the lack of a coherent bourgeoisie in France before the revolution, it is important to point out that a bourgeois revolution need not be led by the bourgeoisie. This was pointed out by many Marxists, including Lenin and Trotsky, who saw the Russian bourgeoisie as too weak and conservative to wage a struggle against absolutism. Because the embryonic bourgeoisie in France was too tied to the absolutist order, it would fall to the popular classes under the leadership of professionals (Robespierre was a lawyer). In fact, neither Soboul nor Lefebvre argued that the commercial bourgeoisie spearheaded the revolution, even though they did tend to underplay how much the bourgeoisie was integrated into the absolutist order. A key part of the revolution, and the one that dealt the greatest blow to the old order, as pointed out by Lefebvre, was the revolt of the peasantry against seigneurial dues. Rather than a self-conscious bourgeois subject coming to power and proclaiming a fully formed capitalist system, bourgeois revolution is better understood as a process in which the old feudal order is negated through class struggle and a state order is established that provides the framework through which capitalism can develop.[41] When it is the feudal ancien régime that stands as a barrier to the development of capitalism, then it is through the class struggle of the classes exploited by this order that these barriers are weakened. Because of the role of class struggle in this process, it makes no sense to speak of a “purely political” revolution as Furet does.

The effect of the French Revolution on the development of capitalism was contradictory. The social historians tended to focus on the revolution as opening the way for capitalism, downplaying the ways by which it delayed capitalist development. On the other hand, revisionists like Cobban argued that the revolution was purely negative for the development of capitalism and perhaps set it back. The truth was that its relation to capitalist development was contradictory. The revolution’s blow to seigneurial tribute on the peasantry meant the removal of economic burdens on them, which allowed them to risk investing in greater specialization, paving the way for the development of polyculture.[42] The privileges of nobles had been abolished and a republican form of rule was established, taking the state out of the hands of the church. A unified national market was formed, with feudal barriers to internal trade removed. Yet at the same time, the peasantry’s traditional land ownership rights were strengthened, preventing the dissolution of the peasant community into capitalist farmers and wage laborers.[43] This was the key contradiction of the revolution: through the mobilization of the peasantry the old feudal order was weakened, yet this mobilization simultaneously strengthened the peasant and delayed the development of capitalism in France.

While it could be argued that the strengthening of peasant land ownership makes it misleading to call the French Revolution bourgeois, this only makes sense if one sees history as a linear process without contradiction. It makes more sense to see the bourgeois revolution as a process, one for which the French Revolution was a particular breakthrough. Another way to look at it is by focusing on the degeneration of the revolution into Bonapartism. Because of the incoherence of the bourgeoisie in France, this class was incapable of ruling as a class. Neither was the proletariat, existing too only in an embryonic form, or the peasantry, incapable of forming their own institutions and thus representing themselves. Therefore, as Marx would later comment regarding the degeneration of the 1848 revolution, the peasantry had to be represented. The result was the regime of Napoleon, a representative who “must appear simultaneously as their master, as an authority over them...that protects them from the other classes and sends them rain and sunshine from above.”[44] Rather than breaking through to the full rule of the bourgeoisie, the balance of classes in France led to the formation of what Marx would call Bonapartism, after its helmsman who stood as arbiter between the classes yet affirmed the state as a state for itself. This represented the maintenance of many of the revolution’s gains, but also a step back towards absolutism, eventually leading to a restoration of the monarchy. While this may complicate the social historians’ narrative of a clear-cut bourgeois revolution with no complications, it by no means entails abandoning their model of class analysis to capture these nuances.

Revolutions are complex events, composed of contesting classes that bring their own interests into play, and these classes are themselves divided into various factions. It is often in the process of revolutions that classes develop their own ideologies and self-understanding, producing a political program to express their social interests. The French Revolution saw the creation of groundbreaking forms of bourgeois political rule even if it did not see the creation of the bourgeois economy in its ideal form. It saw the creation of a democratic-republic that was short-lived, yet set a standard for all revolutionary democrats to aim for. Popular movements that were groundbreaking in their radicalism formed and mobilized on a mass scale. Even if the rise of the bourgeoisie takes on central importance to the narrative, the French Revolution is not reducible to a bourgeois revolution alone. For example, the urban class struggles of Sans-Culottes, the radicalism of the Enragés, and Gracchus Babeuf’s Conspiracy of Equals point to a future socialist movement, suggesting a world beyond bourgeois right. Yet in the grand historical scheme, there is a class that ultimately wins out and benefits the most. In the case of the French Revolution, we can say that this class was the bourgeoisie. The revolution paved the way for the social and political ascension of this class, not just in France, but worldwide.

Conclusion

The revisionist turn cannot be separated from its deeper political implications, its aim to deemphasize the idea that history can be understood in terms of class struggle, or that history is even intelligible as something which contains progress; it posits instead that history is simply a series of power discourses, in which relations of domination are merely shifted in different ways. While the revisionists may have pointed out some flaws in the works of the social historians, these flaws are not sufficient enough to abandon an understanding of the French Revolution in terms of class conflict. Clearly, the complexity of the French Revolution means that we cannot simply view it in terms of a binary conflict, bourgeois versus feudal. Yet the alternative of revisionists is to simply make the revolution irrational, a sort of freak accident with no deeper causation in history. In this world, we can only understand the rioting of peasants and the conflicts between artisans and speculators as a sort of irrational mob violence inspired by ideology run amok and demagogic intellectuals, where instead there is class struggle undergirded by deeper class antagonisms. To the revisionist historian, these class struggles are just a pointless waste of human life without reason. The end results of the revolution are not to drive history forward, but merely to replace one set of rulers with another. There is neither progress nor regress, merely changing the culture and discourse of domination. This alternative understanding of the French Revolution was of great help to those who wished to see an end to revolutionary politics, and it is no surprise the most vocal exponent of it was Furet, and ex-Communist Cold Warrior like any other. If the French Revolution could be shown to have no relation to human progress, then there was no ground for revolution itself to have a potentially progressive role, unless it perhaps occurred in the most orderly way. It was a perfect historical reading of the past for the “end of history”.

The response to the overturning of the social history of the French Revolution should not be to mindlessly cling to dogmas and dismiss the revisionist historians as bad actors. It would be a miracle if Lefebvre and Soboul got every detail of the French Revolution right, and there is no doubt that they could often follow a rigid Marxism. We must engage with the critics of Marxism and social history if we are to improve and ultimately fine-tune our own analysis. Yet even as a foil to contend with, revisionism is weak. As an alternative, the likes of Furet merely offer only confusion and cover for reactionary ideas. Historical studies that focus on revolutionary political culture may open new vistas of research, yet when unanchored by a materialist class analysis they are exercises in the hobbyistic study of antique aesthetics that tell us nothing about their greater meaning in history. Even if the idea of bourgeois revolution was completely discredited, it would be necessary to understand the French Revolution in terms of class struggle as a heroic episode in the narrative of human emancipation. It is this aspect of the social historians’ project that will always be relevant. The capitalist class today want us to see history as random events with no causality with no logic or sense of progress so that we resign any hope of becoming subjects of history that can change the world. The French Revolution is significant because it is exactly the opposite of resignation to the established flow of history as described by our rulers, a revolt against those hierarchies and dogmas said to be eternal in favor of a society based on the agency of humans. It is for this reason that the bourgeoisie hates Jacobinism rather than proclaiming it as part of their historical heritage. To quote Lenin:

It is natural for the bourgeoisie to hate Jacobinism. It is natural for the petty bourgeoisie to dread it. The class-conscious workers and working people generally put their trust in the transfer of power to the revolutionary, oppressed class for that is the essence of Jacobinism, the only way out of the present crisis, and the only remedy for economic dislocation and the war.[8]

It no is surprise then that the historiography of the French Revolution has always been an ideological battle. The earliest disputes between the monarchists and republicans with a decaying aristocracy in the background foreshadowed the later debate between revisionists and social historians, debates that were informed by Cold War struggle between global camps of Soviet Communism and Western capitalism. Today, when our future history is uncertain, those who aim to struggle for a world beyond oppression and exploitation will also have to struggle over the meaning of the French Revolution.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- Historian from 'romantic school', wrote a 7 volume history from 1847-53 ↩

- French historians and statesman who helped form a Constitutional Republic in the July Revolution 1830 ↩

- A political leader who wrote during the 3rd Republic ↩

- For an overview of earlier historiography see Peter Davies, The Debate on the French Revolution (Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 2006) ↩

- Michael Löwy, “‘The Poetry of the Past’: Marx and the French Revolution,” New Left Review, 177 (September/October 1989), 112. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Jean Jaurès, A Socialist History of the French Revolution (London: Pluto Press, 2015), 1 ↩

- Lenin, Can ‘Jacobinism’ Frighten the Working Class?, First published in Pravda No. 90, July 7 (June 24), 1917. Accessed from: https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/jul/07a.htm ↩

- Albert Mathiez, The French Revolution (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1964), 343. ↩

- Albert Mathiez, Bolshevism and Jacobinism, First Published in Le Bolchevisme et le Jacobinisme. Paris, Librairie du Parti Socialiste et de l’Humanité. 1920. Accessed from: https://www.marxists.org/history/france/revolution/mathiez/1920/bolshevism-jacobinism.htm ↩

- Georges Lefebvre, The Coming of the French Revolution, ed. and trans. by R.R. Palmer (United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 2005), 2 ↩

- Albert Soboul, A Short History of the French Revolution, ed. and trans. by Geoffrey Symcox (Berkley: University of California Press, 1977), 5. ↩

- Soboul, A Short History of the French Revolution, 121 ↩

- Albert Soboul, The Sans-Culottes (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980) ↩

- Lefebvre, The Coming of the French Revolution, 2 ↩

- Soboul, A Short History of the French Revolution, 4 ↩

- Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party, in Marx-Engels, Collected Works, V1, 50 vols, New York 197, pp. 486-9 ↩

- Georg Lukács, History and Class Consciousness (London, 1983), 185 ↩

- Alfred Cobban, The Social Interpretation of the French Revolution. (London: Cambridge University Press, 1965), 12-13 ↩

- Ibid., 79 ↩

- Ibid., 164-165 ↩

- Cobban, The Social Interpretation of the French Revolution, 54 ↩

- Ibid., 28 ↩

- Colin Lucas, “Nobles, bourgeois, and the origin of the French Revolution,” in The French Revolution: Recent Debates and Controversies, ed. Gary Kates (New York: Routledge, 2006), 35 ↩

- William Doyle, Origins of the French Revolution. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 40 ↩

- Bernard-Henri Lévy, Barbarism With a Human Face (London, 1979), 154 ↩

- Perry Anderson, In the Tracks of Historical Materialism (London: Verso, 1983), p. 32 ↩

- François Furet, Interpreting the French Revolution, trans. by Elborg Forster, (London, Cambridge University Press, 1981), 46 ↩

- Furet, Interpreting the French Revolution, 159 ↩

- Ibid., 171 ↩

- Ibid, 178 ↩

- Ibid., 187-8 ↩

- Lynn Hunt, The Family Romance of the French Revolution. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), xiii - 6 ↩

- Joan Landes, Visualizing the Nation: Gender, Representation, and Revolution in 18th Century France. (New York: Cornell University, 2001), 2 ↩

- Brenner, Robert. "Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe." Past & Present, no. 70 (1976): 30-75 ↩

- Marc Bloch, French Rural History (London: Routledge, 1966), 117-20 ↩

- J.H.M. Salmon, Society in Crisis, France in the Sixteenth Century (London: Methuen, 1975), 287-290 ↩

- Ibid., 291-92 ↩

- Perry Anderson, Lineages of the Absolutist State (London: Verso, 1974), 18-19 ↩

- Colin Mooers, The Making of Bourgeois Europe (London, Verso, 1991), 47-49 ↩

- Jim Wolfreys, “Twilight Revolution: Francois Furet and the Manufacturing of Consensus” from History and Revolution ed. Mike Haynes (London: Verso, 2007), 56 ↩

- Ibid., 61 ↩

- Mooers, Making of Bourgeois Europe, 70 ↩

- Karl Marx, “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte,” Karl Marx: The Political Writings (London: Verso, 2019), 573 ↩