Richard Hunsinger examines the origins of the capitalist mode of production through a comparative analysis of the work of Jairus Banaji and Robert Brenner.

Introduction

“Across the sea the Apocalypse rises each morning along with the sun. Don’t turn back, don’t be imprisoned by your history. Take to the sea, sever the hawsers that have kept you moored to the land, keep your mind on the prow and take to the waves. Let’s take to the waves. One world is ending, another beginning; this is the Apocalypse and we’re in the midst of it. Help me to equip the boat that will weather the storm.”1

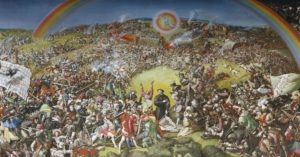

These words are spoken in a moment of Luther Blissett’s novel Q where our protagonist, a radical Anabaptist militant that lives the Reformation through direct, even crucial, participation in its most pivotal struggles, the Münster rebellion in the German Peasants’ War, now finds himself taken in by the members of an urban commune in Antwerp. His guide, Eloi, takes him through the streets and ports of this vibrant commercial center in order to illustrate that the Apocalypse sought by the most millenarian prophets of the struggles amongst the peasants and rural towns of the German lowlands is already well underway. A new age of capital and its production surrounds the body of the old world. The princes, priests, and lords that our soldier had come to see as not only exploiters of a faith available to all, but also of the lives and property of all, were already subsumed into an objective power greater than the fear of God: the divine world of the commodity and the command of capital, its subordination of labor required for the instantiation of their constitutive relations of exploitation. The rallying cry of Thomas Müntzer and his vanguard acolytes of the peasant war, “Omnia sunt communia,” could appear an anachronistic communism to the peasants and their capacities at the time, given their eventual and nigh inevitable defeat. Yet it also presages the determinate negation of this new order from the negated classes themselves. Even at its origins, the capitalist epoch’s transience could be glimpsed.

The language of “Apocalypse” carries through into our own time, one in which similar horizons of struggle are certainly not absent, but the paths beyond them remain obscure. The desire to understand the dynamics of social transformation lie at the heart of the question of the origins of the capitalist mode of production, often known popularly as the “transition” debates. In 1950, Paul Sweezy opened his text The Transition From Feudalism to Capitalism with the words “We live in the period of transition from capitalism to socialism; and this fact lends particular interest to studies of earlier transitions from one social system to another.” Immanuel Wallerstein of World Systems Theory fame would dedicate his work to “those who are seeking to understand the world-systemic transition from capitalism to socialism in which we are living, and thereby to contribute to it.”2 The late 20th century’s collapse of the dreams of world socialism would go on to make these statements appear presumptuous at best, and gravely mistaken at worst. We now live in a time where capitalism’s global triumph has given way to deepening cyclical crises, emerging and intensifying almost as suddenly as this victory over its alternatives was hailed. Even as the apparent horizon beyond capital appears to recede, its ultimate transience makes itself apparent more than ever, inscribed in the immiserated lives that it reproduces the world over.

While the sense of an Apocalypse prevails, epochs do not necessarily come to complete ends, conforming to the quantifications we may come to expect from our own objectified sense of historical time, where the telos of capital accumulation and value relations become synonymous with history as a reified trajectory of indefinite progress. Dynamics of social transformation may emerge from within an apparent disintegration of social systems, but cannot necessarily be said to be automatic occurrences. The optimism of the historians and theorists of the 20th century attest to this, as their prognoses can only be understood as conclusions in which the political viability of such economic revolutionizations of social life was present, albeit in forms contested by those internal to these historical movements themselves. The various debates over the origins of capitalism can then be said to also bear an imprint of political implications which bear critical inspection.

What are the political stakes of any question regarding the origins of the capitalist mode of production? This can be harder to discern than one might initially assume. Even if a line of historical research and argumentation is concerned with the question in a politically neutral way, the definition of what is and is not capitalist about economic organization immediately betrays political assumptions that cannot be separated practically from method. What we find ourselves mired in is the complicated problem of historical presentation as one of emphasis, where in any account only specific dimensions of an epoch can be called forth. There is a semblance of a totality that always seems within our grasp, but is persistently elusive, as the passage of our own time and the contemporary struggles of the living provoke critical revisitations and reconstructions of our past. With every conjuncture, our vantage point upon the determinations of the present and its past change. Thus, there is never any one definitive account which we can rely upon indefinitely.

It is also the case that every reconstruction is reflective of the conditions which the conjuncture itself requires us to emphasize. The earliest debates after the publication of Marx’s Capital possess a focus on the agrarian question. This can, in part, be attributed to the section of the first volume which deals with the so-called primitive accumulation of capital, its “prehistory” in the violent evictions of English peasantry from the land, establishing a proletariat dispossessed of its means of production and thus reliant upon selling their labor-power for subsistence mediated by market relations. But it is also the case that these debates were in response to the composition of production relations in the capitalist mode of production’s development at the time, where many regions in Europe still had extensive peasantries and underdeveloped agricultural production, especially in the case of Tsarist Russia, where serfdom was abolished in 1861, yet the peasantry remained a significant social class. Furthermore, the tendency of the capitalist mode of production to produce a global proletariat was not yet established on a world scale. This development can be seen more clearly now, as by the early 21st century we now live in an era of globally integrated capitalist industrial production. The phenomenon is then still relatively new, and the initial debates of the origins of the capitalist mode of production litigated through the question of capital’s penetration into agrarian production relations and industrial development indicate a period in which the creation of a proletariat, its relative historical necessity, was not yet a matter of course.

Marx’s work at that time was apprehended, with his approval, by his most lucid readers as a critical study into the specific laws of motion of a society in which the mode of production is based upon the production of capital, by capital. These laws of motion constitute a historically specific dynamic which distinguishes modernity as a capitalist society from all periods which came before, themselves also defined in and through their own specific laws of motion, constituted of and by specific social relations in the material production and reproduction of their subjective and objective conditions of existence. A difficulty then could be present in the ability to discern, as Marx did in the case of capitalist development in England, the extension of these abstractions in the contexts of other early communist or socialist movements. The famed Zasulich correspondence,3 in which the potential of Russian peasant communes as a basis for establishing a socialist mode of production is discussed, attests to the complications that came with the process by which the critique of political economy, intended as a weapon in the class struggle of the proletariat, would be handled in practical terms.

However, the agrarian question would be taken up in more detail in the works of Lenin and Kautsky, and a critical extension of Marx’s theory of so-called primitive accumulation developed by Luxemburg. Against the Narodniks and their vision of a possible basis for socialism in Russia in the peasant commune, Lenin’s The Development of Capitalism in Russia (1899) asserted that capitalist organization of production in the agrarian countryside, a subsumption of pre-capitalist relations already haven taken hold of the dynamics of Russia’s economy and thus making it a capitalist social formation.4 Despite the critique of the Narodniks of this as a teleological interpretation of the transition to socialism, Lenin actually dispensed with these teleological assumptions, and instead emphasized the social form of production given its social division of labor and integration into markets as commodity-determined production.5 For Lenin, the stakes of this debate were how to engage class struggle in the Russian context, thus the revolutionaries had to contend with their terrain of struggle as one in which the dynamics of the capitalist mode of production prevailed, despite the prevalence of pre-capitalist relations in certain sectors of production. Supplementing this argument, Kautsky would, in The Agrarian Question (1899), go on to illustrate that the tendency of capitalist development was the subsumption of agricultural production by way of the preservation of small to medium scale farming enterprises, as a means of suppressing prices in a manner which would support the wages that could properly support the expansion of industry. Lenin agreed, stating “as we see, the development of agriculture is quite special, quite different from the development of industrial and trading capital.”6 Luxemburg would intervene in these debates, less on the origins of capitalism and its developing penetration, but by way of assessing the dynamics of capitalist reproduction, in which she claimed that the dispossession characteristic of Marx’s theory of primitive or original accumulation actually pertained throughout capital’s process of reproduction.7

These constituted pivotal critical interventions and contributions to a Marxist theory of capitalism’s origins, but also within a context of capitalism’s development in which pre-capitalist relations of production appeared to predominate. The actual establishment of the capitalist mode of production, its interpenetration of less-developed forms as a moment of its constitution, is clearly still present in the background of all these debates. It would not be until the post-WWII era that debates among Marxists on the historical origins of capitalism would become a matter to be ascertained as determined centuries ago, even if it had not subsumed the labor process of all social formations. Maurice Dobb’s work in Studies in the Development of Capitalism (1946) would counter the Lenin and Kautsky position that capitalism originates in the industrial organization of the towns by asserting an argument of capitalism’s origins in the dissolution of feudal relations in the countryside. For Dobb, capitalism cannot be defined solely by practices of investment and trade, but must be understood as a specific class relation between capitalists and wage laborers, through the prevalence of conditions that would make a class of nascent capitalists increasingly reliant on hired labor. The capital relation becomes intrinsically tied to a specific relation to the land, and the organization of production is a matter of the individual capitals which may form from this. Paul Sweezy’s critique of Dobb promoted a position where the growth of commerce and trade were emphasized as disintegrating influences on feudalism. This spurred numerous critiques which saw several other authors consolidate around Dobb’s position, yet no development of the position which saw a dynamic constitution between these historical epochs, and thus no logical connections between them.

This pitting of production and circulation against each other in the debates on the origins of capitalism appears many times, in varying iterations. This often appears as a dispute over not just the historical development of capitalism, but the very definition of capitalism. By the 1970s, this opposition between production and circulation would reappear in the emergence of World-Systems theory and what would come to be known as the Brenner Debate. According to World Systems Theory, a capitalist world system emerges from the organization of global commodity chains of coerced cash crop labor in a dynamic of surplus extraction to more politically consolidated core states. The impetus of this analysis was to incorporate historically uneven patterns of development into an understanding of capitalism as a system that posits its own global expansion. For proponents such as Immanuel Wallerstein and Giovanni Arrighi, what defined this model as one of capitalist development was the construction of a global division of labor and relations of unequal commodity exchange. Thus, imperialism exists as a dynamic intrinsic to capitalism at its outset. The political incorporation of capitalism into the institutions of the modern state becomes the primary concern. However, what is lost in this analysis is a specificity of capitalist social relations, and what we have instead is a historical model that appears to refract back upon history the geopolitical dynamics of the post-war imperial consolidation of 20th-century capitalism. Within this paradigm, the complex dynamics of colonization and the capitalist organization of pre-capitalist social relations and labor processes as value relations of capital through their reciprocal determinations cannot be accounted for, and neither can internal dynamics of production relations in a labor process subsumed by capital.

Robert Brenner’s historical intervention, the notorious Brenner Debate, would take to task these “circulationist” positions, as well as those of Dobbs, Sweezy, and theories of demographic decline inducing adaptations to the labor process. For Brenner, and for proponents of his position, such as Ellen Meiksins Wood, the primacy of the dynamics of capitalist transition lie in the class struggles of the English countryside, and the relative determination of a balance of class forces conditioned by the class structure of production of the context. The critical importance of Brenner’s position was to combine the economic determinism of debates on the class structures of agrarian production relations with the historical instances of class struggle which demonstrated this transformation as anything but uncontested by the populations it subsumed and subordinated. For a class of proletarians to emerge as wage laborers, the connection of the peasantry to the land must be dissolved. Brenner as well pulls the course of his analysis from an understanding of class struggle and conflict that comes from Marx, though does not follow his critique of political economy to the letter. In his own critique of the World Systems theorists, Brenner demonstrates quite clearly the inability of their thesis of underdevelopment as determinate of capitalism to account for a capitalist dynamic of industrial development to emerge in a tendency to increase productivity. For Brenner, this can only be explained as direct command and domination of surplus labor, and this cannot be solely explained by the growth of trade or commerce.

While Brenner’s position certainly advanced the possibility of determination in political conflict and the crucial dimension of a balance of class forces in this matter, the integration of circulation as a determination in the coherence of capitalism historically is still a crucial element to the mediating forms which nurture the development of capitalist social relations. What we still have in many fields of these historiographic debates is a disposition of alignments with Brenner’s thesis, and various adherents of a World Systems approach, both of which have their own flaws. However, Jairus Banaji’s work has gained greater attention in recent years and constitutes another critical intervention that allows us a more dynamic understanding of capitalism’s origins. Banaji shifts the focus from the English countryside to demand a more global understanding of capitalism’s emergence, but he goes further than the reduction to trade and static conceptions of interstate relations a la World Systems theory, instead looking more closely at commercial capitalism as a form of capitalist production organized by a class of merchants to incorporate a dynamic analysis and critique of Marx’s historical categories and assumptions. For Banaji, Marx’s categories can allow us to pursue a history in which capitalist subsumption is a dynamic process, reconfiguring relations of production in a broad diversity of places. The social constitution of economic forms and the construction of capital’s tendencies in contexts previously considered completely pre-capitalist encourage an analysis of form, content, and mediation in historiographic analysis, as well as closer attention to the relative development of the East in relation to the West’s eventual supremacy. What we have, through Banaji, is an investigation into specific forms of capital in the constitution of capitalism as a distinct reproduction of social relations. István Mészáros also emphasizes the consistency of this concern with Marx’s work as such: “‘Capital’ is a dynamic historical category and the social force to which it corresponds appears — in the form of ‘monetary’, ‘mercantile’ etc. capital — many centuries before the social formation of capitalism as such emerges and consolidates itself. Indeed, Marx is very greatly concerned about grasping the historical specificities of the various forms of capital and their transitions into one another, until eventually industrial capital becomes the dominant force of the social/economic metabolism and objectively defines the classical phase of the capitalist formation.”8

Today, Brenner’s and Banaji’s positions are currently expressed as opponents in a debate, curiously one in which they themselves have not yet engaged. The aim of this essay is to posit that while their two positions can be read as in conflict with each other, they need not necessarily be so, and in fact offer complementary dimensions of historical analysis which can grant us a dynamic understanding of capitalism’s emergence not as the result of pure economic determinism or an altogether contingent series of moments, but as the result of a protracted era of class struggle in which social transformation was induced and conditioned by the crises and struggles of the late feudal epoch. Understanding this problem of the emergence of capitalism is intimately tied to concerns of a transition beyond its transience, for what becomes clear is also that the crises of capitalism’s contemporary state is a product of its reproduction of relations of class domination, and not solely an abstraction lording over all, but an abstraction created by practical activity and socially constituted forms of its mediation. To evaluate the works of Robert Brenner and Jairus Banaji, a critical synthesis must be undergone which also grounds the analysis in Marx’s work on both his theory of the value form of capitalist social relations and historical materials on the constitution of these forms.

In handling Marx’s economic categories in historiographic analysis and interpretation, what is most important is the ability to discern the function of these formal categories in the historical movements which constitute the formation of the capitalist mode of production. Rather than comparing historical analysis of the origins of the capitalist mode of production through the identification of these categories historically, we must be rather more precise and able to locate their specific adaptations as forms that function as moments in the capitalist mode of production and its formation. This is a different task and one in which primary historical documentation does not always correspond to the actuality of the process as we are able to discern it, but only long after the moment has passed. Most importantly, the debates over the origins of the capitalist mode of production have as much to do with the definition of “capitalism” of successive interlocutors as it does with historical accounts. At stake in this is our ability to properly historicize our own situation, as we tread a careful balance between the threat of naturalizing capital’s modernity and its social forms across all of human history, or of identifying such a definitive break that we are always lost, searching for the one moment of transformation and continually making that which came before less intelligible as modernity becomes more exceptional.

There exists a tension between the various histories of capitalism and their respective political commitments; historiography is far from a neutral practice. The adherence to Marx’s work as an evaluative measure of understanding the historical emergence of the capitalist mode of production is not because he possesses the “best” or most historically grounded account. It is rather due to the fact that fidelity to Marx’s project is fidelity to a partisan analysis that takes the relatively conscious transformation of social relations and their interrelation to the unconscious imperatives exacted upon agents as its primary concern. The critical study of history must then be less about being more correct and then be about the ability of such accounts to demonstrate to us the dynamics of social transformation of these times and the roles that agents, the interplay between the structural contours of necessity and their motivations, played within them. We are then not here concerned with an overarching economic history, which merely traces movements on the broadest scale possible, as impressive as such a feat may be. Marx does not give us a single historical account of the capitalist mode of production, but rather an analysis of its social forms and the dynamics of their social constitution and reproduction, the historical tendencies and laws of motion of this specific mode of production as a distinct historical epoch, thus its fundamental transience and the means by which its transformation may be effected from within and a new social form can be born from within the old. The importance of the historical specificity of Marx’s analysis of the capitalist mode of production derives from the understanding that people do indeed make their own history, but not always consciously, much less in conditions of their choosing. In order to become conscious agents of social transformation, they must adequately grasp the specific limitations of their own time, and what options are afforded or precluded by these limitations.

In the interest of contributing to this study of the dynamics of social transformation, the focus of this essay will be that of a comparative historiographic analysis of positions on the question of the origins of the capitalist mode of production, and an evaluation of their particular strengths and weaknesses. The works of Robert Brenner and Jairus Banaji are often read in opposition to each other, as conflicting accounts of capitalism’s emergence and the question of a historical period of “transition.” While these accounts differ significantly in their approach and emphases, it is our position that they can be approached critically as complementary dimensions in the project of constructing a Marxist approach to historical analysis. As the most sophisticated popular accounts (among Marxists, at least) of these historical questions, a critique generated by actually placing them in dialogue will be a generative practice. In order to achieve this, this essay will comprise three sections.

First, we will approach Marx’s analysis of the value-form and its relation to the category of abstract labor as the historically specific social form of labor. A dynamic analysis of these economic forms as historical categories in Marx’s analysis, the specific logical relation in the process through which these categories come to be social forms of capitalist relations, is essential to grasp so as to understand what distinguishes the capitalist mode of production from those modes of production which preceded it. This will serve as a foundation for how we evaluate the works of Brenner and Banaji in the following section, where their approaches to the question of European peasantries and the penetration of capitalist social relations into agrarian production will be assessed. There will be a specific focus on the relation of the entrenchment of feudal relations in Eastern Europe to the emergence of a capitalist dynamic of industrial development in England between the 15th and 17th centuries, but this is not for the purpose of pinpointing a single historical or geographic determination for the advent of the capitalist mode of production. It will rather be for the purpose of assessing their respective contributions to the form-determination of capitalist production and its constitutive social relations, and the formation of a capitalist dynamic of reproduction through the historical process of class struggle and its uneven trajectories. The final section will approach this analysis of class struggle and the capitalist mode of production’s origins through the question of commercial capitalism, as a distinct form of production capitalistically organized by merchants, and the state form and its functions as a necessary element of the consolidation of an emergent capitalist class formation. We hope for this to illuminate specific aspects of the determinations rooted in class struggle in the process of formation of the capitalist mode of production, and further that political and economic forms are expressions of value relations as dynamics of a balance of power always in contention with itself, driving this dynamic of capitalist development and expansion. Capitalism cannot be properly apprehended without contending with its continued existence as the reproduction of its social forms by way of adaptations to continued engagements of class struggle, and the state as a social form in which the organization of production is manifest as the organization of class domination.

I. Social Form & History

Marx tells us in volume one of Capital that “nature does not produce on the one hand owners of money or commodities, and on the other hand men possessing nothing but their own labor-power. This relation has no basis in natural history, nor does it have a social basis common to all periods of human history, It is clearly the result of a past historical development, the product of many economic revolutions, of the extinction of a whole series of older formations of social production.”9 The categorial exposition of the first parts of the work is a logical development of an entirely specific historical process. It is likewise with the categories examined themselves. “The economic categories already discussed similarly bear a historical imprint. Definite historical conditions are involved in the existence of the product as a commodity.”10 The social form of the product as a commodity implies an entire history of its emergence as such, and so too is it the case with the money form. Value’s specificity as an economic category and form that finds material expression through these formal bearers is essential to capital. Yet we are cautioned on the equivalence of these forms with this mode of their historical operation. “If we go on to consider money, its existence implies that a definite stage in the development of commodity exchange has been reached. The various forms of money (money as the mere equivalent of commodities, money as means of circulation, money as means of payment, money as hoard, or money as world currency) indicate very different levels of the process of social production, according to the extent and relative preponderance of one function or the other. Yet we know by experience that a relatively feeble development of commodity circulation suffices for the creation of all these forms.”11 We learn that exchanges operating with money as a mediator are still in accordance with lesser developed regimes of commodity production and circulation. Already the assumption of the commodity’s immediate existence as indicative of the capitalist mode of production is complicated. Money can serve these functions without becoming a functional form of capital. What is it that distinguishes this mode of production and the social form of capital from that of the money form? He goes on to clarify: “The historical conditions of [capital’s] existence are by no means given with the mere circulation of money and commodities. It arises only when the owner of the means of production and subsistence finds the free worker available, on the market, as the seller of his own labor-power. And this one historical pre-condition comprises a world’s history. Capital, therefore, announces from the outset a new epoch in the process of social production.”12 It is the social relations between people themselves that give these mediating forms their specific functions as forms of capital, specifically, those of the owner of money and means of production on one side, and that of the mere bearer of labor-power on the other. This is a historically given condition, not by the appearance of material expressions of the form itself, but the activity and relations of the agents that comprise its content.

It is then necessary to expound upon the role of Marx’s work in relation to an adequate theory of the emergence of the capitalist mode of production, or, rather, the epoch of capital as a social form constituting the totality of social relations. Capital cannot be read as a work of history, yet its object is essentially historical, in its relation to both its prior development that is a premise of the exposition, as well as the fundamental transience of this mode of production to which Marx aims to draw out as a conclusion of his work. What is at work in Capital is not a history, but rather a demonstration of the conjunctive synchronization of social forms as categories of the capitalist mode of production in their unity as moments of a distinct process, with a specific directional dynamic.

The starting point of the commodity is thus not the basis of a historical investigation, but rather that of an investigation that seeks to reveal the categories of social life as determined by the capitalist mode of production through the logical self-development of these categories at the level of simple, immediate appearance. The apparent self-movement of the commodity reveals a social form of determinate relations that, in reality, grounds and conditions its movement. This ground is not an absolute nature, but an edifice that is constructed historically in the positing and reproduction of this movement, giving it the appearance of a self-movement, and marking it as distinctly conditional. Given this, it is not the objective to merely reveal that the ground of the categories of capital is the social labor of the human species, but that this social labor takes a historically specific form:

“[The commodity] is no longer a table, a house, a piece of yarn or any other useful thing. All its sensuous characteristics are extinguished. Nor is it any longer the product of the labour of the joiner, the mason or the spinner, or of any other particular kind of productive labour. With the disappearance of the useful character of the products of labour, the useful character of the kinds of labour embodied in them also disappears; this in turn entails the disappearance of the different concrete forms of labour. They can no longer be distinguished, but are all together reduced to the same kind of labour, human labour in the abstract.”13

This social form of human labor is thus not merely an expression of a concrete unity of the various kinds of concrete labor, but a complex unity which grants these various concrete laborers a definite and distinct social form in their aggregate relation to each other: abstract labor. This category of abstract labor is then revealed as the definite “social substance” of value:

“There is nothing left of them in each case but the same phantom-like objectivity; they are merely congealed quantities of homogeneous human labour, i.e. of human labour-power expended without regard to the form of its expenditure. All these things now tell us is that human labour-power has been expended to produce them, human labour is accumulated in them. As crystals of this social substance, which is common to them all, they are values – commodity values.”14

This “substance” of abstract labor is only present through its crystallization, or said another way, in so far as it is capable of assuming a definite form of appearance in which its motion can be guaranteed. To render labor abstract is itself nothing but a presupposition for its appropriation in “congealed quantities” of this “phantom-like objectivity.” Value is then this relation of abstract labor to itself, as a basis for a metabolic process of social production conditioned around the form of the commodity and the development of value as the corresponding abstract form of social wealth. What is most important here, and is most apparent, if yet unsaid, is that Marx’s exposition of these categories bears throughout the precondition of exploitation in their specific role in relation to capital. The category of abstract labor, as the social form of labor in the capitalist mode of production, is one in which human labor enters into a stage of its development, where it is within a given relation of appropriation in which its specific product ceases to be the end goal of the material production of wealth, and rather the articulation of the substance itself is the basis for the formation of value. Value is then a relation of exploitation and one which is conditioned by human labor in the abstract, or abstract labor, as the basis for social mediation. A distinct logic of its organization then emerges:

“However, the labour that forms the substance of value is equal human labour, the expenditure of identical human labour-power. The total labour-power in society, which is manifested in the values of the world of commodities, counts here as one homogeneous mass of human labour-power, although composed of innumerable individual units of labour-power. Each of these units is the same as any other, to the extent that it has the character of a socially average unit of labour-power and acts as such; i.e. only needs, in order to produce a commodity, the labour time which is necessary on an average, or in other words is socially necessary. Socially necessary labour-time is the labour-time required to produce any use-value under the conditions of production normal for a given society and with the average degree of skill and intensity of labour prevalent in that society.”15

Labor-power, as manifest in its relation within the values of the world of commodities, is an articulation of this social form. The commodity is the individuated articulation of the social form, whereas labor-power is a commodity that resists individuation through its relation to value as the conditional existence of abstract labor such that it can be made to “create” value. That is, as the commodity is a universal form that transmits itself through the relation of particular iterations of itself to each other, labor-power is the appropriable form of this abstract labor in the form of the commodity. This homogenization of social activity is subsumed within a distinct constellation of relations which comes to articulate the relation of exploitation as one in which the individuated, atomic units of labor-power, through their exploitation, condition a social average of their consumption in the production process of commodities through the temporal axis of labor-time. This socially necessary labor-time acts not as a conscious mechanism in the regulation of production and allocation of labor in the capitalist mode of production, but as a substantive relation between the various sites of production and the social validation which these values receive through their mediation in the act of exchange which realizes their values. The temporal axis of commodity value, as expressed in socially necessary labor-time, is thus the result of this relation of abstract labor to itself within a distinct dynamic motion of its appropriation, as value, and its exploitation, as a labor-time which can be adjusted according to the socially-determined conditions of production, which now emerges as social production in a capitalist form through this constellation of relations in process. This gives rise to a distinct form of social production. As Marx says:

“In a society whose products generally assume the form of commodities, i.e. in a society of commodity producers, this qualitative difference between the useful forms of labour which are carried on independently and privately by individual producers develops into a complex system, a social division of labour.”16

This social division of labor cannot be apprehended as a simple category specific to the organization of divided tasks on the level of any given community but refers specifically to the organization of social production between the social aggregate of independently expended labor-powers in an atomized organization of social production where producers carry on independently of each other, where their relation to each other only occurs through the self-movement of the commodity in circulation in the world market. This relation is expressed as competition between producers, a dynamic which, as a form of turbulent, indeterminate “regulation,” is a mutually constituted and reciprocally conditioning war of all against all. It is in this crucible that labor times and conditions of production find articulation as “socially necessary.” What is necessary here is that which is deemed necessary by the social validation of exchange in the market, as values are realized. It is necessary then to understand what is at stake in the distinction between the direct exchange of products and the circulation of commodities, which finds expression through an exchange process, for these are distinct moments. As Marx states, “The circulation of commodities differs from the direct exchange of products not only in form, but in its essence.”17 This essence appears in the money-form of capital which acts as the independent, material expression of value. “It is however precisely this finished form of the world of commodities – the money form – which conceals the social character of private labor and the social relations between the individual workers, by making those relations appear as relations between material objects, instead of revealing them plainly.”18 The adequate expression of this form is to be found in the advent of what Marx terms ‘world money,’ a money relation that exists as the locus within which these relations are expressed in a concentrated unity of their diverse concrete acts of labor as a new universality, capable of expressing the value of all commodities generally. As the material appearance of this particular social form of labor, money that functions as capital consists of a uniquely abstract kind of social wealth, proper to a scale of circulation only possible with generalized commodity production.

“In world trade, commodities develop their value universally. Their independent value-form thus confronts them here too as world money. It is in the world market that money first functions to its full extent as the commodity whose natural form is also the directly social form of realization of human labor in the abstract. Its mode of existence becomes adequate to its concept.”19

The circulation of commodities and the appropriation of the products of labor as values in the independent and autonomous form of money is thus an expression of an essence peculiar to the capitalist mode of production, one in which human social activity is subsumed into the functional composition of its deployment as abstract labor. This relation is expressed through this money crystal, as a form within the totality of social relations of production constituting the commodity form of the product as a bearer of value. It is thus a form in which the intangible temporal axis of exploitation within which this regime of abstract labor is situated is capable of being appropriated by agents which function as money-holders within this totality, deployed to the expansion of their value in this money-form as a means of continually instantiating abstract labor as a social form.

It can be remembered above, however, that this abstract labor has been described as a “social substance,” a “homogeneous mass,” which would seem to deprive it of the quality required for expansion. This language connoting a concrete materiality would appear at odds with its “phantom-like objectivity” in the form of value. How does an abstraction expand itself? After all, what is capitalism without the endless pursuit of greater and greater profits, of a self-induced need for ever more growth, for the sake of itself? These categories, then, cannot be assumed to possess a static character, but to describe a particular motion in which they are continually constituted by their respective agents within definite relations. With regards to abstract labor, Marx presents us with a clear moment in which its own dynamic motion of reciprocal determinations of form are revealed through the ongoing dialectical constitution of the abstract and the concrete as distinct, yet interpenetrating moments of a single unity in the social form of abstract labor:

“On the one hand, all labour is an expenditure of human labour-power, in the physiological sense, and it is in this quality of being equal, or abstract, human labour that it forms the value of commodities. On the other hand, all labour is an expenditure of human labour-power in a particular form and with a definite aim, and it is in this quality of being concrete useful labour that it produces use-values.”20

There is an apparent ambivalence here in Marx’s characterization of abstract labor, one in which we are both granted credence to the physiological interpretation of its being a physical act of expenditure in its expenditure, and one in which its “particular form” is too presented as a distinctive quality, its possession as such of a “definite aim,” an abstract form in its being a socially-constituted form which reaches back into its concrete determination as the producer of use-values through its exploitation. Yet while this physiological interpretation is insufficient alone, and mistakes the result of the social form for its existence itself, the social form is unintelligible without this generalization of human activity which actively constitutes and defines its specific articulation as the formation of capital-as-process. The physicality of human labor is then necessarily understood as a presupposition of the social form’s determination, though it is not identical to it. Thus, in this dialectic of abstract and concrete, abstract labor is a social substance only insofar as this process of subsuming the concrete labors in the totality of social relations of production as human labor in the abstract is continually instantiated by the production and circulation of commodities, through their translation into universally intelligible values in the money-form of their appropriation. Its being as substance, rather, is a process of its becoming-substance, an ongoing substantialization characterized by the subsumption of human social activity as labor within the social form of abstract labor, and thus able to be appropriated as the commodity labor-power.

Money is not always identical with abstract labor, and thus also all exchange is not necessarily the realization of the exchange value of a commodity. For money to be the representation of abstract labor, there exists an entire history of the conditions required for human labor to itself function abstractly. The realization of this condition is in the appropriation of the commodity labor-power, through the emergence of a definite class of laborers whose entire subsistence can only be guaranteed by the sale of this special commodity for a wage. Why is this commodity special, as opposed to all others? Because it is the commodity whose consumption in the production process creates value, the only one of its kind. This “creation” of value, however, is contingent upon the realization of this activity in the social validation of exchange, without which the expenditure of labor in the form of the commodity labor-power by which it is purchased ceases to be socially necessary, and therefore useless. This tension is what characterizes the dynamic mediation of capitalist social relations in the process of capital’s reproduction. We all work for each other, thus labor is social, but we do so indirectly as self-objectifying agents producing our own self-alienation as a means of guaranteeing subsistence in the purchase of the product of others’ labor so that this labor-power is never our own.

This forms the basis for capital’s inherent expansionary tendencies internal to its reproduction, as the accumulation of capital is conditioned by this competitive dynamic between atomized sites of commodity production as this ongoing process of expanding the scale of abstract labor as the subsumption of human capacities within a distinct social form, transforming the labor techniques of the production process as capital encounters it and reconstituting these in the circulation of commodities as sites of commodity production and thus moments in the process of substantialization of abstract labor. This character of the product as a commodity is given by the relations of its very production itself. In this regard, Marx’s theory of commodity fetishism is a central feature in articulating the substantive reality of social form which structures and is structured by the content that appears on the surface, as an ongoing process of mutual transformation:

“Whence, then, arises the enigmatic character of the product of labour, as soon as it assumes the form of a commodity? Clearly, it arises from this form itself. The equality of the kinds of human labour takes on a physical form in the equal objectivity of the products of labour as values; the measure of the expenditure of human labour-power by its duration takes on the form of the magnitude of the value of the products of labour; and finally the relationships between the producers, within which the social characteristics of their labours are manifested, take on the form of a social relation between the products of labour […] [I]t also reflects the social relation of the producers to the sum total of labour as a social relation between objects, a relation which exists apart from and outside the producers. Through this substitution, the products of labour become commodities, sensuous things which are at the same time suprasensible or social […] the commodity form, and the value-relation of the products of labour within which it appears, have absolutely no connection with the physical nature of the commodity and the material relations arising out of this. It is nothing but the definite social relation between men themselves which assumes here, for them, the fantastic form of a relation between things.”21

There is not a single atom or ounce of additional matter which enters into the constitution of these social relations themselves in order to functionally become expressions and bearers of value. It is rather their arrangement and organization in relation to each other from which is situated the starting-point of their movements of relating to each other as such which constitutes this process that is capital. The very form in which relations of production are constituted is crystallized within the articulation of their product in its being a moment of the process of their relation to each other, as moments in the becoming of social production at a new and historically specific scale of its relation to itself in the history of the social life of class societies. Likewise, it is this very same social form of labor and its position within the totality of social relations of production which gives it an apparent objectivity beyond the producers themselves. “Their own movement within society has for them the form of a movement made by things, and these things, far from being under their control, in fact control them.”22 The self-objectification as the self-expression of producers as the material reproduction of their own conditions of existence undergoes a dialectical inversion in the development of this social form of production and the subordination of labor as an abstract function in its commodity form of labor-power, to be exploited and appropriated in this alienated form as not merely self-objectification, but a process simultaneously self-alienating and self-objectifying, manifesting as the class relation which is capital.

The import of this transformation of social relations of production, according to Marx, becomes apparent when it is situated historically and can be understood as a specific form of production that does not itself hold a transhistorical existence prior to the moment of its social realization. “The categories of bourgeois economics consist precisely of forms of this kind. They are forms of thought which are socially valid, and therefore objective, for the relations of production belonging to this historically determined mode of social production, i.e. commodity production. The whole mystery of commodities, all the magic and necromancy which surrounds the products of labour, on the basis of commodity production, vanishes therefore as soon as we come to other forms of production.”23 That is, as soon as we come to approach the matter historically, the capitalist mode of production’s organization of the production process as the subsumption of processes of labor as a totality of valorization can be understood through their development of socially mediating forms that relate agents of production to each other through a reciprocally conditioning social metabolism of mutual exploitation. It is the product of a distinctive historical epoch in history, and one which possesses its own laws of motion and progression.

We are given the first developed articulation of this motion and progression once Marx arrives at “The General Formula for Capital”24 where, in his exposition of the transformation in form between commodity and money which characterizes the self-movement of value, he states:

“Therefore the final result of each separate cycle, in which a purchase and consequent sale are completed, forms of itself the starting-point for a new cycle. The simple circulation of commodities – selling in order to buy – is a means to a final goal which lies outside circulation, namely the appropriation of use-values, the satisfaction of needs. As against this, the circulation of money as capital is an end in itself, for the valorization of value takes place only within this constantly renewed movement. The movement of capital is therefore limitless.”25

The entire objective of the capitalist mode of production then is the reproduction of capital as the reproduction of its conditions of existence, and thus the constant expansion of itself through the subsumption of social activity through capital’s positing of itself as limitless. The bind of this unity of apparently separate cycles of the satisfaction of need is merely distinct moments of a unity of process in which social need is integrated within the social constitution of capital’s self-expansion in the process of valorization, taking the process of direct exchange and transforming it into a dual-sided articulation of the reproduction of capital. What marks the advent of the capitalist mode of production as distinct from the historical process of transformation, as described by Marx above, is the distinctive teleological positing of itself that capital induces as the directional dynamic of the society founded upon its production, and one in which temporal and spatial logics come to be subsumed under as well. Capitalist history is the formation of a distinct and spiraling moment of its own reproduction, one in which transformation is a constant feature. Yet it is a transformation that must continually take its subsumption of social activity as a reconfiguration of such within the regime of abstract labor and functionally reconstitute this dynamic as it encounters its own limits. Of the capitalist, we also find a distinct social logic:

“As the conscious bearer [Trager] of this movement, the possessor of money becomes a capitalist. His person, or rather his pocket, is the point from which the money starts, and to which it returns. The objective content of the circulation we have been discussing - the valorization of value – is his subjective purpose, and it is only in so far as the appropriation of ever more wealth in the abstract is the sole driving force behind his operations that he functions as a capitalist, i.e. as capital personified and endowed with consciousness and a will. Use-values must therefore never be treated as the immediate aim of the capitalist; nor must the profit on any single transaction. His aim is rather the unceasing movement of profit-making. This boundless drive for enrichment, this passionate chase after value, is common to the capitalist and the miser; but while the miser is merely a capitalist gone mad, the capitalist is a rational miser. The ceaseless augmentation of value, which the miser seeks to attain by saving his money from circulation, is achieved by the more acute capitalist by means of throwing his money again and again into circulation.”26

The class relation of capital is capable of accommodating variety. However, as can be observed through any attention to historical detail, the capital relation requires a polarization within which this variety of articulation is constituted in relation to itself as such. These are, namely, a class of money-owners and possessors of the proprietary claims on value. These may exist in a material-physical form as the infrastructures and landed property of the production process, or an abstract-social form as the money-form of value in its universal intelligibility. This value is animated in and by a class of those who can only access these elements of social production and subsistence through their submission to the exploitation of the capitalist class formations by selling their living labor capacity, constituted in its commodity form labor-power, in its purchase that constitutes the mediation that is the wage-relation. These separations are posited by the presupposition which conditions their formation in the organization of social production as determined by the commodity form of the product.

Yet, if we are to understand this history as not a natural, but rather a social, expression of the development of the species as a social being in relation to itself, them this particular class relation, one that is characteristic of the fetish character of relations mediated by the commodity form of social production as appearances of fixed social relations in their moments as crystallizations of process, and the means by which they historically really manifest as “crystallizations,” must be discerned. The fetish of the commodity is the objectivity which these relations appear to possess. That this is an antagonistic social relation driven itself by the class struggle which it induces is not sufficient alone. But is the key to understanding the advent of its realization as a social form. For the accumulation of capital, as Marx illustrates in his work, is not a mere amalgamation of objects in quantifiable expression, but is a specific socially constituted set of conditions that make the reproduction of this dynamic of capitalist production, and thus the materialization of value and its self-expansion as surplus value, possible in a concrete manner. Surplus value is then not an object produced, but an expression of the continuity of this relation itself as an expanded reproduction that latches onto the various forms which constitute its material shell. Likewise, the temporal axis of domination that characterizes the formation of value as a social mediation of exploitation and social law of real appropriation through labor-time as an expression of the manipulation of abstract labor’s substantialization is constituted by the ability to divide the temporality of the working classes into so-called necessary and surplus labor-time, the latter of which being the explicit object of the capitalist’s aims of limitless self-expansion of their capital’s value, and is conditioned by the competitive pressures to maximize its activity. Capital, as a relation, can be adequately described then as the “command over surplus labor,”27 or rather, the command of human activity posited beyond itself in an alienated form of objectivity, and thus a relation which continually constructs itself as the subsumption of that which forms its material limits: the human agents themselves which form the basis for the self-movement of these relations of exploitation.

The categorial exposition of Capital is then not a historical approach to the development of these categories as they are found in the bourgeois science of political economy. Rather it is one that, from the starting-point of the commodity, develops the logical self-movement of the capitalist mode of production through the relation of these categories to each other as a process of the social constitution in which the social forms at play posit their own presuppositions, an enveloping movement back into themselves as moments of this process that is capital’s social relations in motion. The following developments of the “hidden abode of production” proceed from this foundation of the dialectical form-determination of these movements of social constitution, by way of both abstract example and historical record. Capital is thus inseparable from these specific laws of motion that subsume moments of the life process of the species as moments of itself and thus condition the articulation of a distinct temporality within the overall historical existence of social life where the constant transformation and reconstitution of the elements of the process return into a dynamic reiteration of this formal homogeneity.

It is here, however, where the problem of origins comes to the forefront, for if capital is a result of a logical self-development in which class struggle exists as an internal moment that is also conditioned in its expression by the process itself, what is to prevent the development of a naturalized conception of the capitalist mode of production as an objectively necessary stage in the self-development of society? Marx resolves this through the conception of a “primitive” or “original” accumulation of capital, a moment in which the capital relation itself must be enacted in a concrete manner, and in which the commodity labor-power is, in a sense, truly “produced” as a distinct internal object of the capitalist social form.

“In themselves, money and commodities are no more capital than the means of production and subsistence are. They need to be transformed into capital. But this transformation can itself only take place under particular circumstances, which meet together at this point: the confrontation of, and the contact between, two very different kinds of commodity owners; on the one hand, the owners of money, means of production, means of subsistence, who are eager to valorize the sum of values they have appropriated by buying the labour-power of others; on the other hand, free workers, the sellers of their own labour-power, and therefore the sellers of labour.”28

There exists a necessity of a confrontation between these positions within the social polarity of the capitalist mode of production’s essential class relation, in which their unity can properly constitute the process of valorization in a social form adequate to the concept of capital itself. Capital, commodity, money, and labor-power are here all reciprocally determining presuppositions of each other, though in an absence of a moment of their conjunctive synchronization, do not fulfill the requirements of a valorization process. This moment is one which Marx provides a brief discussion, historically locating it in the dissolution of the feudal epoch. While the above passage paints this encounter as an abstract moment of exchange, we have also learned that the advent of this exchange is the product of an entire history of conditions that make it possible and functional as a capitalist relation. Though its precise unfolding is beyond the scope of Marx’s development of this “original” moment of accumulation, we locate it in a relative condition of this overdetermination of social forms and their presupposed relations to each other:

“Hence the historical movement which changes the producers into wage-labourers appears, on the one hand, as their emancipation from serfdom and from the fetters of the guilds, and it is this aspect of the movement which alone exists for our bourgeois historians. But, on the other hand, these newly freed men became sellers of themselves only after they had been robbed of all their own means of production, and all the guarantees of existence afforded by the old feudal arrangements. And this history, the history of their expropriation, is written in the annals of mankind in letters of blood and fire.”29

“In the history of primitive accumulation, all revolutions are epoch-making that act as levers for the capitalist class in the course of its formation; but this is true above all for those moments when great masses of men are suddenly and forcibly torn from their means of subsistence, and hurled onto the labour market as free, unprotected and rightless proletarians. The expropriation of the agricultural producer, of the peasant, from the soil is the basis of the whole process. The history of this expropriation assumes different aspects in different countries, and runs through its various phases in different orders of succession, and at different historical epochs.”30

It is then made clear that this very transformation, this realization of a historically specific epoch in the development of social production, is constituted as a process through this very dispossession. This moment is itself the essence of the accumulation of capital, as also demonstrated earlier by Marx in “The General Law of Capitalist Accumulation.”31 This expropriation is the necessary moment that constitutes the self-movement of capital in the conjunctive synchronization of its elemental categories. Further, expropriation is here given by Marx to be not a single moment, but an integral feature of the emergence of the capitalist mode of production. That it assumes a variable character of intensity and the application of force allows us to interpret Marx’s examples of the enclosures of the English peasantry as not the original accumulation of capital itself, but merely one example in what is an implicitly varied succession in a field of social relations of commodity production and market-mediated circulation which presuppose and posit this very expropriation as an overdetermined condition of the fulfillment of their own reproduction through the self-expanding process of valorization. As a “lever” in the course of the formation of a distinct capitalist class, this very expropriation amounts to a victory that is not merely economic, but political in its concrete determination and in the articulation of its reproduction.

“It is not enough that the conditions of labour are concentrated at one pole of society in the shape of capital, while at the other pole are grouped masses of men who have nothing to sell but their labour-power. Nor is it enough that they are compelled to sell themselves voluntarily. The advance of capitalist production develops a working class which by education, tradition and habit looks upon the requirements of that mode of production as self-evident natural laws. The organization of the capitalist process of production, once it is fully developed, breaks down all resistance. The constant generation of a relative surplus population keeps the law of the supply and demand of labour, and therefore wages, within narrow limits which correspond to capital’s valorization requirements. The silent compulsion of economic relations sets the seal on the domination of the capitalist over the worker. Direct extra-economic force is still of course used, but only in exceptional cases. In the ordinary run of things, the worker can be left to the ‘natural laws of production’, i.e. it is possible to rely on his dependence on capital, which springs from the conditions of production themselves, and is guaranteed in perpetuity by them. It is otherwise during the historical genesis of capitalist production. The rising bourgeoisie needs the power of the state, and uses it to ‘regulate’ wages, i.e. to force them into the limits suitable for making a profit, to lengthen the working day, and to keep the worker himself at his normal level of dependence. This is an essential aspect of so-called primitive accumulation.”32

The “transition” to capitalism, rather, the historical emergence of this mode of production as a process, is thus not automatic, but requires the consolidated organization of a distinct and emergent class of the rising bourgeoisie to find expression as capitalists through the political force of the state, and, in this social form of the state, control the limits of a social formation’s reproduction such that a working-class comes to be produced, constructed, maintained as an integrated moment as an objective condition of its existence. This is the essential production of a proletariat by capital as a source of surplus labor. The development of the dependence on capital by these distinct class formations is a result of class struggle and is necessarily the outcome of the concrete terrain of political class conflict. The state form is here necessary to the emergence of the capitalist mode of production, and one which cannot be interpreted as an externality to the compulsion of these economic relations but rather a moment of the expression of emergent relations of force between classes that comes into formation through the development of an antagonistic conflict between their respective conditions of existence and the organization of subsistence relations. The antagonisms of this class struggle are preserved and transformed by their reproduction in the social form of capital.

Marx does not provide us with a concrete chronological history of the feudal epochs dissolution. What we have, rather, is, on the one hand, an exposition of the categorial elements of the capitalist mode of production and the manner in which all, as presuppositions of capital, posit it in and through their relations within the conjunctive synchronization of their movement as the process of capital. On the other hand, we have, by way of example, an illustration of the means by which this synchronization of these elements come to exist and function as moments of this process. The very self-movement of capital is a result of the political class struggle, and one in which the bourgeoisie plays a role as the bearers of capital proper, the character-masks of the initial realization of a mode of production that is characterized by a distinct mode of class domination that is achieved politically and conditioned economically, successively reproduced by these mediations as the organization of social production through universalized social relations of exploitation.

Where the so-called transition period presents its greatest problems is in its existence as a moment in the formation of the specific teleological dynamics of capital’s process and the uneasy emergence of this process from within a distinctly pre-capitalist epoch itself. The stakes of any investigation into the transition era require us to properly understand the relationship between the social constitution of these formal determinations that presuppose the concrete realization of capitalist social relations of production as this occurred through the dissolution of the feudal epoch and from within the material shell of that waning age’s political and economic structures and the contours of the political class struggles that animated this transformation of pre-capitalist social life into the society founded upon the capitalist mode of production. This task is nothing short of reconciling a consistent problematic coherence of the unity-in-process, transformation and reconstitution, as real moments of a concrete history made by human agents, but which comes to dominate them. In short, the historical dialectic is not just an abstract model with which we attempt to make sense of this world, but a reality of the contradictory and uneven character of its formation.

II. Class Struggle & Emergent Mediations

The establishment of capitalist social relations and a capitalist dynamic of industrial development, in the context of agrarian production dominated by the serfdom of the feudal epoch, has several key matters of importance. First, the matter of mediating forms of subsistence which are dominated by the wage relation, and not by any direct production of subsistence by the producers, is an essential moment in the ability of money to function as capital through its purchase of labor-power and therefore the constitution of abstract labor as the social form of labor. With producers still capable of some relative capacity for the autonomous determination of the use of their means of production and their product, the capitalist mode of production cannot develop with the appearance of a self-moving dynamic of reproduction. The mediation of social reproduction is not yet wholly integrated within value as an autonomous form of social wealth and regulation of relations of real appropriation.

Second, on the scale of social production beyond the social relations of these immediate agricultural producers, agricultural production is a necessary component to the production of the subsistence of a social formation as a whole, increasingly relevant to the subordination and substantialization of labor as abstract labor as a commercial expansion that brings more and more disparately connected sites of production in relation to and mediated with each other as commodity producers. In order to control the labor of the nascent urban proletariat and developing mediation of the wage relation, the ability to integrate relations of surplus extraction in the serf labor of the countryside became essential to integrating these uneven sites of production into a coherent unity in process.

Third, the organization of feudal estates as sites of production and their adaptation and transformation into sites of commodity production integrated into the mediating infrastructure of commercial expansion, characteristic of these periods, would necessarily have consequences on the political roles and functions of extant state forms. As we are dealing with the instantiation of a historically specific labor regime of abstract labor, we must account for the specific means by which value’s appearance as abstract social objectivity is actively constructed and maintained. Its agency is not that of the form itself, but a dynamic that is politically and economically constituted for those it benefits, as much as it emerges from the appearance of economic necessity for these exploiters, as well as the exploited.

Finally, given the political import of these developments in the organization of production and subsistence relations, the dynamics of feudal “dissolution” must rather be understood as a period of the self-transformation of the extant social relations of production into an emergent dynamic of capitalist reproduction. Within this dynamic, the determinate class struggles over the development of the mediating forms of this totality’s construction are an essential part in the social constitution of a specific relation of its categories and the ability to articulate their conjunctive synchronization as a coherent process of reproduction, and therefore an expression of the realization of a particular dynamic of class domination and relations of exploitation. We come head to head with the problem of being able to coherently discern a moment in which feudalism decisively “ends” and capitalism proper “begins.” It is our contention that there is rather a continuity between the qualitative distinctions of these epochs that are maintained by the same element which constitute the dynamics of its transformation, that is, class struggle. Feudal class domination’s transformation into capitalist domination and its successively impersonal forms necessarily emerged through the preservation of class rule that predates capitalist society, albeit in distinct forms of appearance and execution.

In the interpretation of this historical transformation, we encounter a problem of the capability of clearly periodizing a moment of its initiation, as if the measurements that we deploy onto time are themselves adequate to locate a precise location of such social developments, assuming that they conform neatly to this logic. This forces us to acknowledge that, to a great extent, our ability to cleanly articulate a distinct “feudalism” as it stands in relation to a complete “capitalism” dabbles in abstractions that do not necessarily conform to the contours of historical moments as carefully as one would like, as a means of referring to the specific processes which constitute an epoch’s material and social reproduction. What we do have, however, is a clear passage from an epoch in which a distinct dynamic of development guided by the accumulation of capital and the self-expansion of value emerges from within a definite basis of social relations of production not yet determined by this process. There are many ways in which this pre-capitalist world contained within itself determinations of capital as immanently-posited, yet could only be made as such through the determinate construction and organization of this process as a unity of itself, and ultimately requiring a capacity to not only command labor but to command the surplus labor of the producers within a production process through this unification of capital as the determination of the successive forms of production and circulation.

The so-called passage of history gives us no single account of this self-transformation that is necessarily definitive. What we have available to us are accounts in which the location of the determinant factors in the constitution of this process’ instantiation and realization of itself as a unity, presenting the possibility of capital’s self-developing social totality as a concrete reality. This is not an automatic telos of history, but rather a telos that emerges as the consequence of the determination of specific agents acting within definite relations. Following this, we wish to undergo a comparative study of two of the most developed and currently discussed arguments in the literature on the origins of capitalism, those of Robert Brenner and Jairus Banaji, and appeal to their complementary strengths and dynamism, in order to develop a more adequate theory of Marxist historiography that can aim to satisfactorily synthesize these contributions and understand them on their own terms.

We can see the approaches of both Robert Brenner and Jairus Banaji as articulating to us complementary dimensions of the dynamics of transformation. For Brenner, we are to locate the determinate role of political class struggle and patterns of development given by class structures and social property relations conditioning the viability of making this transformation. For Banaji, the immanent potentiality of the capitalist mode of production is also already given by these structures, but through closer attention to this internally constituted dynamic of positing capitalist social relations that are already apparent in the dynamic of capital as a social form that exists in more antediluvian forms of appearance. The social forms of mediation that emerge from this period of feudal crises, themselves crystallized moments of a dynamic, encapsulate the laws of their epochs. It is our contention that Brenner’s focus on the determination of political class conflict and struggle lacks attention to this process’s own role in the social constitution of the mediating forms which come to articulate the construction of a capitalist social totality as an integrated, complex unity. Banaji’s own dialectic does not fully account for the agentic transformation of these forms of mediation into a specifically capitalist mode of production, and risks imparting upon the entirety of pre-capitalist social relations an inevitability in this economic determination, contra his own questions of the non-inevitability of capitalism. Through a comparative synthesis of their approaches, we can rather demonstrate the necessity of constructing a historical dialectic that understands political class struggle and social forms of mediation as reciprocally determining dimensions of a single process in the material reproduction of social life, interpenetrating movements in the form-determination of capital.

The debate sparked by Robert Brenner’s essay “Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe” still yields insight into the role played by extant class structures and the definite composition of social production in the feudal epoch as one in which the development of capitalism was a process of self-transformation. He articulates his position following a critique of the demographic and commercialization theses prevalent at the time of his writing as thus: