Introduction

On March 3rd, 1946, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) announced that they were starting Operation Dixie, an ambitious new plan to organize unions in the South. The headline story boasted that the CIO’s leaders were making “plans for one of the greatest organizing drives in labor history,” organizing “millions of unorganized workers in Southern states” placing “special interest” on the region’s booming textile industry.[1]

This ambitious vision to bring unions to the anti-labor South would not succeed. Starting in 1947, barely a year into the organizing drive, the CIO began to narrow the scope of the project, reducing the number of states it included, as well as the resources they devoted to it. It would carry on in limited capacity for a few years, until the CIO formally ended Operation Dixie in 1953, as they prepared to merge with their former rivals in the American Federation of Labor (AFL). At that time, the CIO had won just 64 of the 232 union elections they contested through Operation Dixie, less than 30%, and had actually lost members in the coveted textile industry.[2]

The failure of such an ambitious and necessary project should worry those of us building the labor movement today. It raises a number of difficult questions, including: Can you organize on a mass scale in an area hostile to labor? What does it take? In this article, I will lay out a history of the project and discuss a number of its structural failures, while contrasting it to successful labor organizing taking place in the same time and region. From this, I intend to draw out some key understandings for contemporary labor organizers, and provide a nuanced look at an often forgotten part of US labor history.

King Cotton

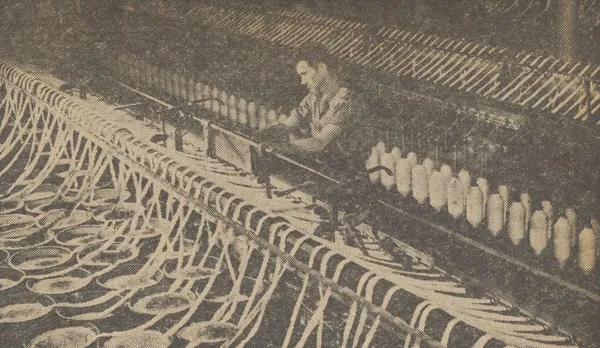

To understand Operation Dixie, we must begin with the context of the Southern textile industry. The textile industry was the engine of growth for the post-Civil War Southern economy. When Northern troops left the South at the end of Radical Reconstruction in 1877, politicians and businessmen sought to regain the power that they had lost during Reconstruction. Big landholders began to consolidate their holdings, accumulating the capital necessary to open textile mills. At the same time, tenant farmers and small land holders faced decreasing agricultural profitability. For example, from 1880 to 1920, in Durham County, North Carolina both the average size of a farm and the percent of farmers owning their own land shrank by a third.[3] In response to this agricultural crisis, families began looking for ways to supplement their income. Many families began sending members of the family, typically women or children, to earn money in factories during the off-season for the farm. This only exacerbated the instability of small farms, and gradually families abandoned farming entirely, with all members of a family taking jobs in textile factories and moving into company owned housing adjacent to the mills. Employment grew nearly 10 percent per year from 1870 to 1900, as textile mills and surrounding mill villages sprung up across the South in a crescent-shape across the Southern piedmont from Virginia to Alabama.[4] Most mill jobs and mill villages were exclusively white. Black workers were confined to poorly-paid non-production jobs, such as cleaning, and resided in segregated neighborhoods.

Starting in 1929, the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) began to send organizers to these Southern textile mills. Many of these CPUSA organizers were labor movement veterans, including many who had organized in the textile industry in the North. This effort was part of the larger CPUSA labor strategy. At their 1929 convention, CPUSA rejected their previous strategy of boring from within the established trade unions of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Instead they developed a three-pronged labor strategy: organizing their own unions through the Trade Union Unity League (TUUL), while also maintaining opposition movements within certain AFL unions, and creating looser industrial leagues where they were not strong enough to launch full-fledged, national industrial unions.[5]

The reasons for this new CPUSA strategy were twofold: first, it reflected their own experiences working within the AFL and the establishment American labor movement, which was often hostile to their political aims. Secondly, this labor strategy was influenced by Communist International (Comintern) policy. During this time, known as the Third Period, the Comintern saw worsening economic conditions globally as leading to an imminent world revolution. To the Comintern, this necessitated a decisive break with Trotskyism, reformist socialism, and liberalism to build independent Communist bodies, including labor unions.

In the textile industry, the CPUSA established the National Textile Workers Union (NTWU), an independent, Communist alternative to the AFL’s United Textile Workers of America (UTW) which did not have a large presence in the South. Many of the NTWU organizers had experience in the Northern textile industry, but conditions in the South were more difficult than those in the North. Southern textile workers made 30-50% less than their Northern counterparts, and many many Southern textile workers lived in mill villages, which were tightly surveilled by management. Furthermore mill owners were often very well connected, and had influence over local police and politicians, leaving many workers rightfully afraid of retaliation.[4] Despite the challenging conditions, NTWU organizers encountered agitated workers, due to deteriorating working conditions, including the “stretch out,” a speed up of work with no raise in pay. This allowed NTWU to have some success in organizing unions and collective actions. Most famously, NTWU organizers and rank and file leaders organized a strike at the Gastonia Mill in North Carolina in 1929 that garnered national attention. Although the Gastonia strikers lost, it was a great display of worker power and solidarity, with one young striker describing it as “the first time I’d ever thought things could be better.”[6]

As mass strikes in the AFL and the rise of industrial unionism in the CIO began to achieve success in depression-era America, many TUUL members and organizers rejoined the mainstream labor movement. At the same time, the Comintern began to prioritize coalition work in response to the rise of Fascism. Combined, these two trends spelled the end of the TUUL, and by extension the end of NTWU, along with other Communist-led unions in the South, some of which were having great success organizing black workers.[7]

A Whole New Atmosphere

At the start of WWII, union density was very low in the textile industry, as the CIO’s Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA) had made very limited gains in the South. Mill owners took advantage of this, and expanded their textile operations, which were booming from wartime demand in the non-union South. Here, mill owners were able to offer raises to textile workers while still keeping labor costs lower than in the union North.

This rapid growth caused an increase in living standards along with a rise in wages for textile workers. Where a generation earlier a Southern textile worker lived in a company owned shotgun shack, by the end of WWII, textile workers were renting or buying homes and modern consumer goods, such as refrigerators and cars. Junius Scales, a North Carolina Communist, described these post-war mill towns as “a whole new atmosphere.”[8]

Thus, when the CIO launched Operation Dixie in 1946, they were up against a rapidly changing industry which presented a number of new challenges. Many TWUA organizers struggled to make inroads with textile workers, who remembered the harsh union-busting of the 1920s and 1930s and feared retaliation from mill owners. The small, rural towns where textile mills were located were functionally company towns, and mill owners were often tightly connected to politicians and police, making many workers afraid to get on management’s bad side. Furthermore, there was often limited outside employment in these towns, particularly for women, which further heightened workers fears of retaliatory firing. Another issue in the post-war landscape was that many of the luxuries creating this “new atmosphere” were purchased on consumer debt, leaving workers both more prosperous and precarious than their counterparts a generation earlier.

These issues would be in conflict with the strategy laid out for TWUA organizers by the CIO under Operation Dixie. The CIO pursued an aggressive, strike-heavy strategy, which required significant resources and buy-in from workers. These strikes were typically over recognition or refusal to bargain a first contract, rather than unfair labor practices or subsequent contracts in established unions. Strikes on these issues are more risky, as losing the strike means losing union recognition. Many of these strikes did fail, in part because of the strength of the textile industry and power of mill owners. During a 1948 strike in Siler City, North Carolina, a TWUA organizer reported that “none of our people broke ranks” but that the company “had been advertising [for scabs] all throughout the state, South Carolina, and Virginia” and “company representatives spent everyday after work, and every weekend, scouring the countryside for scabs.”[9] Furthermore, “manufacturers often supported each other in their efforts to oust unions.”[10] Thus, TWUA was pushing strikes against well-resourced bosses willing to do whatever it took to keep unions out, which would have been challenging for even the most skilled organizers and passionate rank-and-file. The negative results of this strategy were twofold. Firstly, it drained both human and financial resources to pursue frequent strikes, limiting TWUA’s organizing capacity. Secondly, most of these strikes occurred before reaching a first contract, leaving workers without union representation.

The CIO also placed great emphasis on winning as many elections as possible, and then moving on to the next shop, rather than staying to continue to organize for a first contract. According to a report in Textile Labor, one year into Operation Dixie, there were 30 textile mills where an election was held but no contract had been reached.[11] As one TWUA organizer put it, “winning an election is not enough.”[12] Bargaining a first contract is a slow and arduous process that typically takes months, if not years. Without support, many union campaigns fall to management pressure or lose momentum during this process. Furthermore, if a contract is not reached in the first year, a decertification vote can be held, ending the union entirely.

These challenges of rising wages and living costs, and the limitations of a strike-heavy strategy can clearly be seen in the 1951 Danville, Virginia textile strike. Dan River Mills had been a long time leader in textile worker organizing, and had set industry standard pay patterns throughout the region. Two weeks into the 1951 strike, more than half of the mill’s white workers had crossed the picket line. A week later, two-thirds of white workers had crossed the picket line, weakening the union's position to the point that management successfully decertified the union later that summer.[13] Many workers cited high living costs as the reason they had to cross the picket line, a strain that only increases with the length of the strike. For this reason, long strikes require significant worker buy-in and union infrastructure, both of which were vulnerabilities for the TWUA.

The failure of the strike also demonstrated how such a strike-heavy strategy was not suited to the conditions of the Southern textile industry. Norris Tibbetts, a business agent involved in running the strike said that “we made our first mistake in trying to make noises like an industry-wide union, which we are not. We have about 15% organization in the South. A solid strike among what we have organized would affect only 10% of the cotton industry.”[14] Strikes in low-density industries makes it easier for management to hire replacement workers, and causes less of an impact to the overall industry. For these reasons, the TWUA strategy was ill-suited to the conditions of the post-war South. The CIO’s strategy borrowed fully from their Northern experience, where union density was much higher and the textile industry did not exert as much control on the economy, rather than a strategic response to the Southern industry. As Tibbetts put it, “Who the hell are we to act like the UAW and GM?”[12]

The Dan Mill strike reveals another trend: differences between the response of white and Black workers. When a majority of white workers at Daville Mills crossed the picket line, 95% of Black workers remained on strike.[12] While the textile industry was still significantly white by 1946, labor shortages during the war led to more Black workers entering the industry. Roles within the textile industry were still typically segregated, and Black workers still received lower pay.

Union locals, including the Danville TWUA, were also segregated. For Black workers, segregated union locals provided a strong opportunity to represent themselves, and in Danville led to the election of an interracial board of union officers and convention delegates, and no doubt contributed to their strength on the picket line.[15] However, these gains in some segregated locals did not extend to the whole of TWUA activity in the South. Integrated TWUA locals did not offer equal treatment for Black workers with many locals across the South limiting the voice of Black workers in the union, while others barred them from attending altogether.[16] While some TWUA locals did provide advancement for Black workers and improve race relations, TWUA, or even the CIO, does not appear to have had a strategic effort to address the racial question in their organizing, or to advance racial equity through their work.

Given the challenges of the textile industry, it is necessary to consider why the CIO continued to focus on this industry specifically. During WWII, the CIO grew in membership thanks to expansion of their key Northern industries as a result of defense demand, including steel and automotives. As the defense industry expanded they entered into an agreement with AFL and CIO leaders to adopt a higher wage scale across the board, in exchange for the union leaders signing a national no-strike deal during the war. However, this “labor peace” did not extend to non-union shops, creating a “Southern differential” in wages. CIO leaders began to fear that manufacturers would move South to circumvent the unions, undercutting the membership and dues of the CIO and weakening the union.

Organizing textile factories was thus a strategy selected by the CIO based on numbers: as the largest industry in the South it had the potential to shore up CIO membership. By 1945, 80% of the textile industry was located in the South, but only 20% of workers were under union contract, proving a potential for massive CIO membership growth.[17] A series of articles in The CIO News in February 1947, the one year anniversary of Operation Dixie, demonstrated the CIO’s focus on membership growth, highlighting 64 union elections and 14,500 new members in Texas, 22,000 new members in North Carolina and 18 election wins, and 40 New Locals In Tennessee.[18] This membership focused choice not only overlooked the challenges of the textile industry outlined above, but also failed to examine what industries in the South were seeing organizing success.

Civil Rights Unionism

Many of the industries seeing organizing success in the post-war period were those with a large concentration of Black workers. Wartime industry growth had opened up more industrial jobs to Black workers, which were typically segregated, with management giving Black workers the most dirty and dangerous positions first. Although as the war went on, the labor shortage would open up more positions to Black workers. Regardless of their position, Black workers faced harassment, lower wages, and lower job security. In response, they began staging numerous wildcat labor stoppages, such as sit downs and walkouts, for better treatment. White workers responded with “hate strikes'' or labor action to reject what they saw as a challenge to their working conditions in the form of Black labor militancy. Combined, this led to an average of over 10 strikes a day in both 1944 and 1945.[19]

These shop floor tensions between Black and white workers remained high after the end of the war, as management sought to return to the pre-war labor status quo. Evelyn Bates, a Black worker in the Memphis Firestone Tire plant, summed this up, saying that “When the men started coming home from the war, they started giving the men their jobs back, ‘cause it was a man’s job… A lot of the Black womens they laid off. They didn’t lay you off according to seniority,’ cause you didn’t have no seniority over white womens.”[20]

Management used racism to turn white workers against union campaigns. A 1949 strike at Memphis Furniture, one of the largest employers of Black women in Memphis, failed as a result of this anti-union tactic. One Black striker did not “remember seeing any white people [on strike or] at the union hall” during the events of 1949, and said that the almost entirely white upholstery department “kept on working as long as they could.”[14] With white workers continuing to work and refusing to join the union, Memphis Furniture was able to successfully break the strike, despite the fact that “five times, maybe ten times” more Black people worked for the company than whites.[12]

Similarly, an early effort by the CIO’s URW (United Rubber Workers) to organize Firestone workers in Memphis failed because “all of the back voted for the CIO” but “the whites didn’t buy it.”[21] One Black Firestone worker, George Holloway, states that only about 10% of white workers, who made up roughly 65% of the plant, attended a CIO action at this time.[11] After the failure of the CIO to organize a wall to wall union in the plant, the AFL organized white tradesmen which according to fellow Black Firestone worker Clarence Coe “was good for them,” but left unorganized Black workers vulnerable.[22] However, “the CIO promised us [Black workers] justice” and so Black workers continued to organize, with renewed determination inspired by the loss. Holloway recalls that Black workers would “slow down work so the whites couldn’t make any money” until “the whites needed the Blacks to cooperate to make changes in the plant.”[21] URW succeeded in winning recognition at Firestone in 1942, only because they were able to agitate amongst Black workers and refuse to capitulate to white workers' racism, instead showing them how the management exploited the racial division to harm all workers. URW would go on to be an engine for integration in the plant post-War, while many CIO efforts at that time would stall after being unable to organize interracially.

After the end of the TUUL in 1935, when CPUSA reoriented towards working within the CIO, CIO unions with a Communist presence were the most successful in organizing Black workers. The Food, Tobacco, and Agricultural Workers (FTA) are a particularly notable example, as they articulated a Communist-influenced strategy and a political vision including the role of race in worker exploitation. As one tobacco worker in Winston-Salem, North Carolina put it: “They are using the poor whites to whip the [Blacks] and the [Blacks] to whip the poor whites. If the poor whites sort of get out of line, they fire them and put [Blacks] in their jobs and they do [Blacks] the same way.”[23] Communist organizers in FTA understood this relationship between race and exploitation, and used it to successfully organize amongst Black workers, connecting with their experiences of discrimination in the workplace.

Roger Korstad refers to this as “civil rights unionism,” where Black workers used union organizing as a vehicle to fight racial oppression. The Communists offered a program that resonated with Black workers because it “had an explanation of events locally, nationally, and worldwide which substantiated everything they had felt instinctively from their experience. It was right in their guts.”[24] By showing that the union “meant business on racism,” FTA was able to effectively recruit and mobilize Black workers for political action.[12] The Communist approach saw shop floor grievances as one aspect of a larger issue of racial capital, and sought to organize in the community as well. In Winston-Salem, this included participation in local elections and fighting for better housing, through FTA’s strong political action arm. The FTA also began to organize tobacco leaf workers in the Eastern part of the state, who were impoverished, rural, seasonally-employed and overwhelmingly Black. The FTA success with tobacco leaf workers is particularly remarkable, as agricultural workers are excluded from the National Labor Relations Act, which led the TUUL to focus on other sectors of workers.[25] The strategy of the Communist-led FTA contrasts strongly with that of the CIO, who targeted industries based on their ability to provide new members, rather than a political analysis of worker exploitation that extended beyond the workplace.

The Communist led Farm Equipment Union (FE) was also able to break into the South in the post-War era, organizing the International Harvester (IH) plant in Louisville, Kentucky. FE’s organizing materials clarified their political vision: one FE pamphlet read “the southern bosses have for generations played Negro against white, and white against Negro” and “there was a direct connection between this and the fact that Southern workers were the lowest paid in the country.”[26] This analysis that connected low wages to larger conditions of inequality resonated with the IH workers in Louisville, Kentucky. There, the Southern differential was particularly poignant, as International Harvester workers in Indiana, just across the Ohio river from Louisville, were making substantially more. FE remained committed to industrial organizing and integration, and was able to win recognition for a interracial, wall to wall union in 1947.[27] Like FTA, FE would take these struggles beyond the shop floor, challenging segregation throughout Louisville, both in sanctioned union activities and via rank-and-file action.[28] Through their militant shop floor organizing, FE demonstrated to their members that advancement could only be made when all workers acted in solidarity, which they took beyond the gates of International Harvester.

An End To Wildcatting the Year ‘Round

FE, however, faced another challenger beyond the bosses: the United Auto Workers (UAW), who made a national effort to take over FE’s shops, stretching the FE’s resources thinner, which would prevent them from expanding further into the South. FE would lose the Memphis International Harvester plant to UAW. At the time, FE had only three organizers in the city, and their successes and headquarters were far away in Chicago.[29] UAW rejected the militant, Communist vision of FE and instead promised an era of cooperation between management and labor, known as “labor peace.” Walter Reuther, the architect of this strategy, promised “the end of wildcatting the year ‘round,” referring to the unrest of the 1940s.[30] Despite this vision of cooperation, and a large staff and resources, UAW struggled to win the Memphis Harvester plant. International Harvester refused to recognize the union by acclamation for two years, forcing a vote, and continued to exert pressure, resulting in a first contract that included limited gains.[29] The Communist strategy that UAW attacked was producing wins that UAW could not get on their own, leaving them to snatch up members through takeovers.

Of course, UAW was not alone in aggressively attacking Communist-led unions. Following the declaration of the Popular Front in 1935, and the end of the TUUL, Communists began to bore from within the CIO, and maintained a strong leadership presence in a number of unions. In addition to the aforementioned UFW, FE, and FTA, this included the United Electrical Workers (UE), International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), and the Mine, Mill, and Smelter’s Union (Mine Mill). Communists in these unions continued to organize with a theory of class struggle, understanding that “only through solid unity of all workers can people hope to meet with the large companies on even terms. Anything to disrupt this unity, be it color prejudice, religious prejudice, or what have you, is a crime against all working people.”[31] Rank and file leaders in these unions became “fellow travelers,” adopting this organizing outlook without officially joining the Party.

Reuther, by contrast, envisioned a post-War America that “represented an attempt to expand labor’s involvement in helping to administer production in the name of industrial peace and the general welfare.”[32] This vision of shared prosperity, built on cooperation and high production levels, required a reduction in work-stoppages and quelling labor-management hostilities. Thus, in 1945, Reuther tried to channel striking GM workers “toward the pursuit of demands that the company could easily afford to grant, while diverting attention away from more complex local grievances concerning working conditions.”[33] This conciliatory attitude and effort to reduce strike activity led The FE News to claim that “an anti-union corporation yells for help and Walter Reuther comes running to the rescue.”[34]

Of course, fears about Communists in the labor movement, and the expansion of union membership during WWII went far beyond Reuther. When workers launched a series of strikes across a variety of industries in 1945 and 1946 to demand that wartime gains in employment and wages remain, anti-labor and anti-Communist politicians seized the opportunity, and amended the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) to rollback workplace protections. This law came to be known as the Taft-Hartley Act, and among its provisions was a requirement that all union leaders sign affidavits stating that they were not members of CPUSA.

This resulted in a large campaign of redbaiting during the years of Operation Dixie, as anti-Communist politicians, union leaders, and bosses used alleged involvement in the Communist Party to oust radical leaders and turn workers against their unions. The CIO seized on Taft-Hartley’s limitations on Communist involvement in the labor movement to purge the radical unions from the CIO, including FE. The expulsions would set the stage for a series of raids that took place over the next couple of years as the AFL and CIO sought to take over shops previously held by Communist unions.

Anti-Communist Consolidation

In the South, this became particularly tense, as politicians proclaimed that all unions were Communist, and that Communists were on a path toward integration, which would lead to the subjugation of the white race. Mississippi Senator James Eastland went as far as to warn of the “harlemization” of the country. Statements like this were clearly meant to stoke fears about race, which were used to divide the labor movement.[35]

This would have disastrous consequences for radical unions in the South. In 1946, the business friendly Winston-Salem Journal ran a front page story entitled “Communist-Union Collusion Is Exposed in City; Appeal is Made to [CIO President Phillip] Murray for Labor Leadership.” This story appeared three weeks into a pivotal strike by the FTA at R. J. Reynolds, just four days after the passage of Taft-Hartley. The author clearly sought to vilify the Black-led union by warning that communists were “creating class hatred as a preliminary to violence, and finally chaos,” and further alleged that this influence went all the way to CIO president Phillip Murray, ironically an active anti-Communist.[36] The fear mongering about unions was so great that when FTA sought out donations to support the strike, the Fellowship of Southern Churchmen refused to do so without first going on a “fact-finding” trip to determine the nature of Communist activity in the union.[37]

With business owners, the liberal establishment, and the mainstream labor movement, all agitating white workers against the union, the FTA was in danger. In 1949, the AFL and CIO contested the FTA’s representation at the Reynolds plant, part of a series of raids across industries. FTA retained a high level of loyalty amongst Black workers, adopting the slogan “trust the bridge that carried us over,” highlighting the level of trust that their militant organizing on and off the shopfloor fostered amongst Black workers. However, the AFL and CIO divided the white vote, paving the way for “no union” to win a plurality. The final count: No union 3,426; FTA (independent) 3,323; Tobacco Workers International Union (TWIU-AFL) 1,514; United Transportation Service Employees (UTSE-CIO) 541.[38] Despite the CIO’s stated goal of promoting unionism in the South through Operation Dixie, their anti-union campaigning cost workers their union.

Of course, business owners were not content with the defeat of the Communist unions, but continued to attack all organized labor as Communist. During the UAW campaign at the Memphis International Harvester plant, a local paper accused Walter Reuther of being a socialist.[29] Such public attacks were clearly meant to both deter union membership and ostracize those associated with the union.

While themselves being decried as Communists, anti-communist CIO leaders continued to use anti-Communism to consolidate their power. In Memphis, local CIO officials attacked UFWA leaders after the 1949 Memphis Furniture Strike, while national leaders purged Communists from the union nation-wide. This left the majority-Black local without officials dedicated to organizing and building an interracial movement.[39] Thus the CIO’s attacks on Communist unions not only weakened the position of the left-wing unions, but of the entire labor movement in the South.

“A Body Without Spirit”

Given the role of redbaiting in attacks on Operation Dixie and other post-war labor organizing, it is worth examining the big picture consequences of the hunt for Communists in the labor movement, in order to put the decline of Operation Dixie into context.

Following the end of WWII, the US government turned against their wartime ally the USSR, and escalated their pursuit of domestic radicals. At the same time, CPUSA did not return to a TUUL-style strategy of pursuing independent union work. Instead, party members continued to work within the CIO. For many CPUSA members, this meant remaining in unions like the FTA or FE, which were part of the CIO but were widely known and regarded as Communist. However, these unions lacked the support from the Party that the early CIO and TUUL had during the third period, such as the Labor Defense Fund (ILD). Without the institutional support of the Party, members were vulnerable to both the government and the CIO’s attacks on Communists. Radicals who remained in the labor movement at this time often took steps to distance themselves from the Party and refused to disclose their membership status, primarily remaining active as independents and individuals, not as Party members.

By the late 1940s, many Communists had successfully “bored from within” to bureaucratic leadership positions within the CIO. After the 1947 purge of Communist unions from the CIO, Communist labor leaders were either in the left-wing unions that were both underfunded and under attack, or subservient to the anti-Communist leadership that had expelled their comrades. In only a decade, the radical element within the CIO went from a prominent force to fighting for its life.

This had, of course, come at great expense to the CIO as well. Purging Communist unions removed a million members from the CIO, and weakened the position of the remaining unions. This would leave a CIO that was, as one former member put it, “a body without spirit.”[40] To consolidate power and outmaneuver the radical unions, the CIO merged with the AFL in 1953, ending nearly two decades of rivalry. The AFL-CIO would continue to raid shops of the now expelled Communist unions, and all the independent, Communist unions but UE and ILWU would fall in the coming years. Neither of these remaining Communist unions had a strong presence in the South, and the Communist unions who did fell quickly: FE would fold in 1955, FTA in 1954, Mine Mill in 1967. Only UFWA would hold on past 1970, albeit in less radical form, lasting until 1987. It is unsurprising then that union density in the United States peaked in 1953, as the CIO failed to mount an organizing strategy to compensate for the losses in the Communist-controlled unions, and limitations imposed by Taft-Hartley.

The CIO also quietly ended Operation Dixie in 1953, leaving an extremely weak track record. If the CIO hoped to defeat the Southern differential, they failed. If the CIO undertook the project out of a commitment to building a long lasting workers movement, they failed. If the CIO wanted to consolidate membership and power, they won, but because they had joined forces with their historic rival to defeat many of the very organizations that propelled their initial rise to power, not because they defeated the Goliath of the Southern textile industry.

Conclusion

By any measure, members added, union votes, strikes, or contracts, Operation Dixie did not succeed in taking on King Cotton. What are we to make of such a failure?

Historian Barbara Griffiths, in the only monograph on Operation Dixie, called the project “the legacy of a Northern encounter.”[41] In other words, the CIO did not develop an organizing strategy for the South, and was unprepared for the hostile labor and race relations there. Without a larger political analysis motivating their actions, the CIO was unable and unwilling to engage in the long term struggle needed to make inroads in the South. Instead, they left TWUA organizers with a half formed strategy that could not support the needs of workers, even when they were agitated and in favor of the union. The focus on union elections and recognition strikes stretched resources thin, and meant that every loss on the picket line set the campaign back.

At the same time that the TWUA was struggling, Communist labor organizers in the post-war South developed a strategy and accumulated some victories, both on the shop floor and against segregation. Their success reveals a fundamentally different approach to the purpose of a union. For the Communists, a union was an inherently adversarial tool to improve the lives of workers and change society. Communist unions were committed to interracial unionism and organizing Black workers, which gave them an agitated base for their campaigns, while advancing a progressive agenda of “civil rights unionism.”

But as the Cold War took off and turned its attention towards domestic radicals, Communist organizers received the ire of business, government, and mainstream CIO leadership. This left them with dwindling resources with which to fight against fierce raids and decertification campaigns, on top of their usual labor struggles. In summary, we can identify four key failures in Operation Dixie: the strength of the textile industry in the South, an overemphasis on recognition strikes and union elections, a weak stance on integration and the race issue, and the rise of anti-Communism.

All of these decisive issues remain for labor organizers to grapple with today. As organizers take on Target, Amazon, and Starbucks, they are facing business owners just as politically powerful and connected as the mill owners of the New South, and just as ready to bend and break the law. Organizers must keep these conditions in mind as they develop their strategy. Similarly, they must be prepared to take on the long fight; bargaining a first contract can take just as long, if not longer, than organizing for a recognition vote. It is our duty as organizers to inoculate against the idea that the campaign ends at an NLRB vote, and to encourage our coworkers and comrades to build patience. Finally, we as socialists need to articulate a political vision for the power of the workers movement, not only to address issues in the workplace, but throughout the system. This vision and our organizing must be dedicated to fighting inequality, or else risk both alienating our allies and fueling our enemies’ attacks.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- “CIO Launches New Organizing Drive” in The CIO News, vol. 9, no. 10; March 4th, 1946; pg 7. https://archive.org/details/mdu-labor-057493/page/n113/mode/2up. ↩

- Minchin, 32, 1. ↩

- Janiewski, 25. ↩

- Salmond, 2. ↩

- Victor G. Devinatz, “The CPUSA’s Trade Unionism during Third Period Communism, 1929–1934,” American Communist History, vol. 18 no. 3-4 (2019), 251-268, DOI: 10.1080/14743892.2019.1608710. ↩

- Salmond, 33. ↩

- For a more comprehensive study of the third period and popular front amongst Black workers in Alabama, see Robin Kelly’s classic Hammer and Hoe. ↩

- Minchin 22. ↩

- Minchin, 76. ↩

- Ibid, 75 ↩

- Ibid, 69. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid, 134. ↩

- Ibid, 117. ↩

- Ibid, 137. ↩

- Ibid, 140-1. ↩

- Ibid, 1. ↩

- “Texas Leads in CIO’s Southern Campaign” in The CIO News, vol 10, no. 6, February 10th, 1947, 10. https://archive.org/details/mdu-labor-057494/page/n93/mode/2up; “22,000 Join CIO in North Carolina” in The CIO News, vol 10, no. 8, February 24th, 1947, 19. https://archive.org/details/mdu-labor-057494/page/n125/mode/2up; “40 New Locals in Tennessee” in The CIO News, vol 10, no. 5, February 3rd, 1947, 6. https://archive.org/details/mdu-labor-057494/page/n77/mode/2up. ↩

- Lipsitz, 87. ↩

- Honey, 192. ↩

- Ibid, 71. ↩

- Ibid, 79. ↩

- Korstad, 97. ↩

- Ibid, 275. ↩

- Devinatz, 17. ↩

- Gilpin, 165. ↩

- Ibid, 162. ↩

- Ibid, 219. ↩

- Honey, 157. ↩

- Gilpin, 218. ↩

- Gilpin, 212. ↩

- Lipsitz, 109. ↩

- Ibid, 110. ↩

- Gilpin, 179. ↩

- Jeff Woods, Black Struggle, Red Scare: Segregation and Anti-Communism in the South, 1948-68. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004. 43. ↩

- Leon S. Dure Jr., “Communist-Union Collusion Is Exposed in City; Appeal is Made to Murray for Labor Leadership.” Winston-Salem Journal, May 19th, 1947. Courtesy of North Carolina Special Collection, Forsyth County Library, Winston-Salem, NC. ↩

- Korstad, 330. ↩

- Ibid, 407. ↩

- Ibid, 181. ↩

- Boyer and Morias, 361. ↩

- Barbara Griffith, The Crisis of American Labor: Operation Dixie and the Defeat of the CIO. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1988, 169. ↩