Hank Kennedy presents a historical overview of the reactionary Cold War international policy of the Meany/Kirkland era AFL-CIO, with a focus on its relations with trade unions in Central and South America.

Introduction

During the Cold War, the United States engaged in several operations to undermine or overthrow left-wing governments in Latin America and replace them with more pliable ones. Participants in these operations included the Central Intelligence Agency, multinational corporations, the ruling classes of the various countries, and, to its everlasting shame, elements of the American labor movement. This article will catalog, chronologically, the involvement of organized labor in subverting democracy and union rights in Latin America, the efforts by American trade unionists to change their course, and what the ultimate outcome of these efforts has been.

The Meany Years

George Meany was seemingly destined to be the AFL-CIO president. His tenure ran for 24 years, beginning with the merger of AFL and CIO in 1955 and only ending with his retirement in 1979, which occurred shortly before his death in 1980. He outlived more colorful, contemporary union leaders like Walter Reuther of the United Auto Workers (UAW) and Jimmy Hoffa of the Teamsters, casting a long shadow over the future of the organization. He began his career in the United Association of Journeymen and Apprentices of the Plumbing, Pipefitting and Sprinkler Fitting Industry, and was well known for his cigar smoking, his business unionism, and, most importantly, his inveterate anti-Communism.

This attitude manifested itself in a variety of ways. For example, AFL-CIO delegates were required to leave the room at global conventions if unions perceived to be “weak” on Communism entered, such as Italy’s General Confederation of Labor.1 The AFL-CIO under Meany gave uncritical support to Presidents Johnson and Nixon in their crusade in Vietnam, with Meany calling anti-war protesters a “dirtynecked and dirty-mouthed group of kooks.” In 1972, the AFL-CIO refused to endorse Democrat George McGovern for the presidency, citing his support for a unilateral withdrawal of American troops from Southeast Asia. This was the first time that the organization had failed to endorse the Democratic candidate for the office.

This anti-Communist activity extended to Latin America and included activities against Jacobo Arbenz, who was democratically elected president of Guatemala in 1954. Arbenz was not, at this point, a Communist, but he was proposing expropriations, with just compensation, of untilled land currently held by the United Fruit Company. The United Fruit Company was very upset by both Arbenz’s land reform proposal and his proposed Labor Code, which would empower the country’s unions, shorten the work week, and increase the national minimum wage. They were fearful that the company’s ability to earn a profit would be negatively impacted. Arbenz was widely popular among both the organized labor unions and the peasantry of the country, so the company looked for a nondemocratic solution to their problems.

In 1954, UFC’s lobbying efforts to get the United States to intervene on their behalf were rewarded. They managed to convince the Eisenhower administration that Arbenz was a secret Communist, and therefore a national security threat. During Operation PBSUCCESS, the Central Intelligence Agency-trained forces of Carlos Armas invaded from Honduras and toppled Arbenz’s administration, forcing the President to flee for his life. This begat a Civil War that would last until 1994, costing hundreds of thousands of lives.

While this may be well known to socialists, what is usually less well known is the American Federation of Labor’s role in fomenting unrest in Guatemala before the coup. This occurred before the official merger of the AFL and CIO in 1955, but it bears looking into as a precursor to future actions. The AFL worked with the anti-Communist international labor federation the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) to funnel money to oppositional groups in Guatemala preceding the 1954 coup. The AFL also attempted to set up an anti-Arbenz union in the country, the National Union of Free Workers.2 The given reasons for the AFL’s support were that Arbenz was preparing to outlaw independent trade unions, and therefore had to be removed. George Meany later said he rejoiced “over the downfall of the Communist controlled regime in Guatemala.”3 This despite the fact that the new regime was described even by an initially pro-coup trade unionist as repressive and a country in which it was “much more difficult for a trade union to operate and exist.”4 A CIA agent in the country reported that after repression of the trade unions began that in some areas “workers were being paid 50 cents a day and were forced to work 81 hours a week.”5

There was a slight amount of pushback within the mainstream labor movements to this meddling in Central America. The national CIO lodged a protest at the State Department and in an address to the Michigan CIO the secretary-treasurer of the United Auto Workers, Emil Mazey, spoke combatively that “in Guatemala we have made exactly the same blunders that we have made in Indochina and elsewhere….I say we have to change this foreign policy of ours. We have got to stop measuring our foreign policy on what’s good for American business that has money invested in South America and elsewhere.”6 A.O. Knight of the Oil Workers Union and the chairman of the CIO Subcommittee on Latin American Affairs, stated American policy was meant “to give aid and comfort to the United Fruit company.”7 Knight and Mazey’s remarks, powerful though they were, were not enough to prevent the CIO from merging with the Meany dominated AFL the next year, and joining it in its foreign policy doctrines.

When the AFL-CIO merger occurred in 1955, Meany was in undisputed control of the new organization. The AFL-CIO created its own international organization, called the American Institute for Free Labor Development (AIFLD), instead of relying on the ICFTU. The AIFLD was established in 1961 with support from the American State Department’s United States Agency for International Development (USAID). William C. Doherty Jr. was selected as the head of the organization and he described its mission in testimony before Congress as collaborating with business interests in “trying to make the investment climate more attractive and inviting.”8 AIFLD chair J. Peter Grace, who also headed the W.R. Grace chemical concern, said the institute “teaches workers to increase their company’s business.”9 Corporate supporters of the AIFLD included such anti-union companies as Kennecott Copper, Anaconda Copper, IBM, and the United Fruit Company.10 A 1975 article described the school set up by the AIFLD in Front Royal, Virginia for Latin American trade unionists as “a school for scabs.” The school offered a class on how to implement speed ups, so that workers would do more work for the same pay, amongst other subjects.11

When the South American colony of British Guyana was transitioning to independence, the AIFLD and AFL-CIO helped ensure that the country would not choose socialism as their economic model. Eight Guyanese trade union leaders received training at the Front Royal school and used their training to lead a general strike to topple democratically elected Marxist leader Cheddi Jagan. AFL-CIO affiliates like the Newspaper Guild, the Retail Clerks, and AFSCME all helped in strike leadership and in spreading propaganda for Jagan’s opponent, Forbes Burnham.12 Burnham quickly revealed himself to be far more dictatorial than the defeated Jagan, and his administration, which lasted until his death in 1985, was characterized by electoral fraud, corruption, and the murder of political opponents.

In 1964, the Brazilian populist and nationalist President João Goulart was overthrown by military coup, in a manner similar to Arbenz ten years prior. In March of that year, he called for the nationalization of the country’s oil industry, fueling charges made by both the American government and the Brazilian business elite that he was a closet Communist, and therefore hostile to American interests in Latin America. On April 1, a military coup took place that forced Goulart to flee the country and established a brutal military dictatorship that would last from 1964-1985. William C. Doherty Jr. stated on a radio broadcast that the AFL-CIO “became intimately involved in some of the clandestine operations of the revolution before it took place. … What happened in Brazil on April 1 did not just happen-it was planned, and planned months in advance. Many of the trade-union leaders-some of who were actually trained in our institute-were involved in the revolution.” The stated reasons for this deep level of support for the coup were that Goulart was allegedly attempting to illegalize independent trade unions, much like the stated reasons for supporting the coup in Guatemala ten years earlier.

This new government, however, would be even harsher towards than Goulart could ever dream of being. Though Doherty Jr. would say publicly that “I can tell you there are free trade unions in Brazil today,” unionists in Brazil would face severe state repression.13 In 1966, James Jones, a Black organizer for the United Steelworkers, would travel to Brazil on a post coup fact finding mission. He reported that “the leaders of the unions here have the greatest fear I have ever seen in my life. They are afraid to raise their voices on behalf of their fellow workers for fear of police reprisals.”14 Doherty Jr. even encouraged the Brazilian unions to accept a wage freeze saying “you can’t have the poor suffer more than the rich or the poor less than the rich, and if these proper checks and balances are built into the system, the Brazilian labor movement will cooperate in any type of wage freeze.”15 In 1966 another labor leader spoke out against the federation’s work to overthrow left-wing governments. Victor Reuther, the brother of Walter and International Director of the UAW, charged that the AFL-CIO had, in the cases of Guatemala and Brazil, “permitted themselves to be used by the Central Intelligence Agency as a cover for clandestine operations abroad.” He continued that as long as Meany’s associates remained in control “there will be no changes in the federations foreign policy.”16 In 1971 the AFL-CIO passed a resolution condemning the Brazilian dictatorship for its repression of union rights, but by then the damage had already been done.17

Later, the AFL-CIO would play a role in the coup against Salvador Allende in 1973. Allende had been narrowly elected as part of the Popular Unity coalition, which included the Socialist Party, the Communist Party, and others, in 1970 on a democratic socialist platform. This was perceived as an unforgivable Cold War provocation and President Nixon gave the infamous order to the CIA to “make the economy scream” in order to force Allende from power. This plan to overthrow Allende not only involved the CIA, but also multinational corporations like ITT and Kennecott Copper. It also involved the AIFLD. The AIFLD’s initial plan was to split the broadly pro-Allende labor movement, and use any anti-Allende elements to help crater the economy and therefore force the President out of office. Robert O’ Neil, the AIFLD representative in Chile, wrote that the AIFLD could “eventually control the trade union movement here.” The majority of their effort was spent on the Central Workers Union (CUT) , by far the largest union in Chile at that time. However, they were mostly unsuccessful in this effort.18

The President of the CUT was a Communist named Louis Figuerosa and he remained popular amongst rank and file members, despite the AIFLD’s attempts at subversion. O’Neil wrote that “undeniably and unfortunately, the majority of organized Chilean workers still back Marxist leadership, at least in trade union elections.” This failure to effect change was so apparent that the focus was then shifted to financially supporting the National Party, a far-right political organization that was hostile to democracy and openly supported Pinochet’s coup in 1973. In the aftermath of Pinochet’s coup, many trade unionists were rounded up and forcibly “disappeared” no matter what their relationship had been to Allende’s government. Even those in the bus drivers and truckers union, who had received AIFLD funds, opposed Allende, and led strikes against him and his policies, were not safe. Miraculously, Figuerosa escaped, first to the Swedish embassy, then to Mexico. From his exile, he bitterly accused the AIFLD of “13 years of massive social espionage.”

Meanwhile, the executive council of the AFL-CIO released a response after the coup saying “Free trade unionists did not mourn the departure of a Marxist regime in Chile which brought that nation to political, social and economic ruin.”19 The statement also condemned, without any trace of apparent irony, the new Pinochet regime that the executive board had helped install through the AIFLD, in saying that “free trade unionists cannot condone the autocratic actions of this militaristic and oppressive ruler.”20 The International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) took a more direct approach to opposing the Pinochet dictatorship, as its local 10 refused to load bomb parts headed for Chile in 1978 and this boycott was successful in preventing the U.S. Army’s military aid shipment.21 There would be some more serious pushback to this AIFLD subversion from within the AFL-CIO as well, but like the complaints about activities in Guatemala or Brazil, it did not lead to a sustained movement to challenge the leadership. The high point of this opposition was the passage of a resolution by the California Labor Council denouncing the AFL-CIO backed coup. But as in the case of the UAW’s previous objections, it did not translate into momentum for a change in the foreign policy orientation of the union federation.

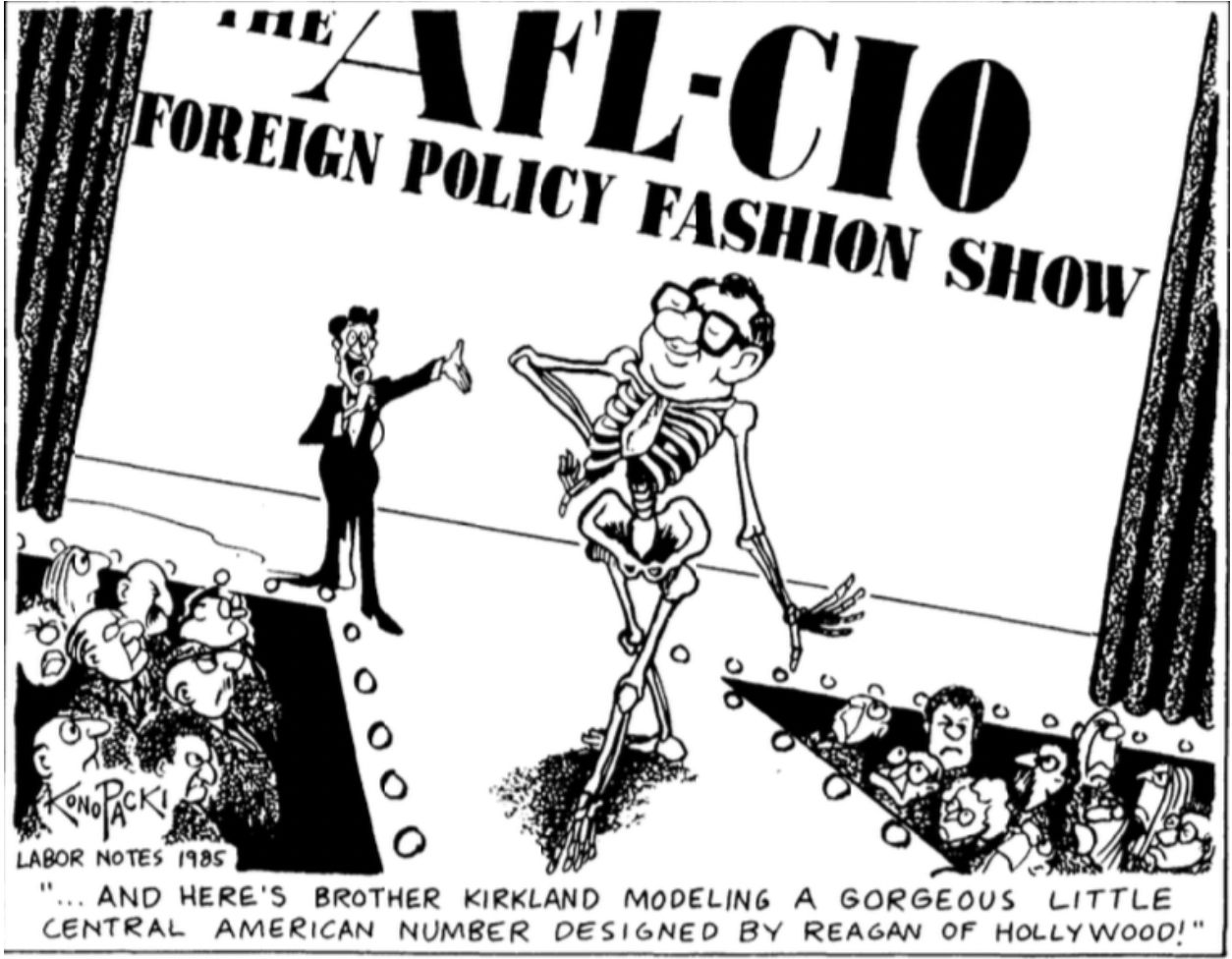

The Kirkland Years

Lane Kirkland succeeded George Meany as head of the AFL-CIO following the latter’s retirement in 1979. He would serve in the position for sixteen years, during an incredibly brutal period in Latin American military conflict. There was no mistaking which side of these conflicts Kirkland was on. Like Meany, he was a hard-line anti-Communist and supporter of American intervention overseas, and he would go on to use union resources to those ends, much as Meany had done.

In Nicaragua, the Sandinistas had taken power in a 1979 revolution against a US backed dictator. The anti-Sandinista strategy employed by the US and the AIFLD was to paint the new government in a negative light and the right-wing contra rebels in a positive one. To that end the AIFLD sponsored speaking tours and publications in the United States which echoed the pronouncements of the Reagan administration, attacking the Sandinistas for their purported despotism and hostility towards free trade unionism.22

In Nicaragua itself, the AIFLD provided extensive support to both anti-Sandinista unions and political parties. This became especially important for the Presidential Election held in 1990. The post-Revolutionary civil war had been going on for eleven years at that point and both the Sandinistas and their opponents looked to the results of the election for vindication. The Confederation of Trade Unity, a union associated with the opposition candidate Violeta Chamorro, received “special cadre training” that included instructions on how to register voters and get out the vote activities. This training bore fruit, as Chamorro was elected and her National Opposition Union was swept into power.23

In El Salvador, where the leftist guerilla FMLN were fighting a military junta, the AIFLD tried a different approach. The AIFLD provided 80% of the budget for Popular Democratic Unity (UPD), a moderate, business friendly trade union that was meant to be a substitute for rebel aligned unions that were subject to state terror and repression. But by 1984, the AIFLD would withdraw its funding from the UPD for the transgression of criticizing El Salvador’s president. After this, the National Union of Salvadoran Workers was formed, with AIFLD support, further damaging the already weak trade union movement by splitting the UPD.24 Longtime union activist Reverend David Dyson has been quoted as saying “in the 1980s, during the reign of death squads in El Salvador, AIFLD threw money at the most conservative and most pro-government union factions.” Furthermore, he says that American unionists advocating against aid to the Salvadoran government would “find AIFLD people sitting around the embassy drinking coffee like they were part of the team.”25

American historian Hobart Spalding puts forth that “the increasing relative importance of the international economy in these years made U. S. workers more receptive to hearing and learning about foreign issues. More and more voices argued for a working-class response to the transnationalization of capital, calling for the transnationalization of the union movement.”26 Historian Andrew Battista takes a longer view, instead writing that “the local labor committees also had institutional roots in developments within organized labor. Most of the unions that joined the NLC [the National Labor Committee in Support of Democracy and Human Rights in El Salvador] had a shared history of political opposition to the top leadership of the AFL-CIO.”27

There were a few reasons for why an opposition movement developed in the AFL-CIO regarding Central American policy. One was the growing prominence of both Vietnam veterans and anti-Vietnam war activists in the federations affiliates. Another was that the union members feared that American intervention would lead to an American invasion and occupation, one whose economic and human costs would be most borne by the working class. For public sector union members, increased military spending came at the cost of other spending, threatening their jobs, wages, and benefits. This was best exemplified by the popular union button “Money for school lunches, not contras.” Finally, union members in manufacturing saw the war on militant unions in Central America as leading to the creation of sites of lower wages and benefits which would lead to the flight of unionized manufacturing jobs to El Salvador or Nicaragua.

The conflict between the leadership of the AFL-CIO and its membership came to a head at the 1985 national convention in Anaheim, California. Prior to the convention, three unions outside the umbrella of the AFL-CIO (the ILWU, the National Education Association, and the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers) had passed resolutions harshly denouncing the Reagan Administration’s Central America policies.28 In the lead-up to the convention, the Cold Warriors within the AFL-CIO launched a tour to combat the growing Central American solidarity movements within the federation. On the tour, William C. Doherty Jr. offered praise for the Duarte Government of El Salvador, even as that government committed numerous human rights violations. Doherty Jr. also claimed that he was opposing “a deliberate campaign of misinformation and deception promoted by the Sanidinista government of Nicaragua and the Communist-led World Federation of Trade Unions.”29 Doherty Jr. was probably referring to the activities of the NLC. In 1985, this group could count on the support of the presidents of 12 AFL-CIO affiliates, including the UAW, the International Association of Machinists, and the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union. Wrote Jack Sheinkman, the secretary treasurer of the last of those three, “they [the AFL-CIO leadership] did everything they could to undermine us and to get some of the international [i.e., union] leaders to withdraw.”30

At the convention the NLC members stood strong, despite pressure from Kirkland and his union supporters. Kirkland marshaled his own forces, including the leadership of the American Federation of Teachers, the Bricklayers, and the Seafarers, all of whom had passed pro-Contra resolutions,31 but a debate was forced at the convention by the NLC unions, a first in the history of the union. There had never been a debate on foreign policy priorities held at a national convention of the AFL-CIO before. Despite this milestone, the debate went on for only ninety minutes, during which NLC members, including Screen Actors Guild President Ed Asner, gave passionate statements supporting civil and political rights in El Salvador and Guatemala and blasting the AFL-CIO for being on the side of those opposing those rights in these countries. Kenneth Baylock, President of the American Federation of Government Employees, declared “I would like for one time for my government to be on the side of the people, not on the side of rich dictators living behind high walls.”32 A verbal counterattack launched by American Federation of Teachers President Albert Shanker who claimed Reagan’s “policy helped human rights” in El Salvador.33

In the end, a compromise was reached, calling for a peaceful resolution to the Central American conflicts. This resolution was shocking since it did not call for the victory of the American backed forces, as had been the case in resolutions past. This also marked a change from previous oppositions to foreign interventions. It had marshaled large numbers of supporters and it had made change at the national level of the AFL-CIO. The NLC then began lobbying members of Congress to oppose aid to human rights violators, in opposition to the positions of AIFLD aligned unions. It also began to grow, as by 1988 it counted twenty union presidents among its members.

The 1987 and 1989 conventions would build on the momentum that the NLC had begun in Anaheim. At both conventions the NLC beat back hard-line resolutions that expressed unequivocal support of the contra rebels in Nicaragua and the military junta in El Salvador, despite the massive amounts of state terror being committed in the latter, particularly against trade unionists. In their place, resolutions were passed that called for an end to state terror and repression and negotiated settlements to those conflicts.

The culmination of the organizing done by the NLC were a pair of demonstrations held in Washington D.C. and San Francisco in 1987. During these 85,000 worker-strong rallies, the presidents of seventeen AFL-CIO affiliates gave speeches attacking the Reagan administration’s foreign policies towards Apartheid South Africa and Central America. Actions such as this helped lead to the reduction of military aid to El Salvador in the early 90s and the tying of that aid to the human rights conditions in the country.34 Similarly to their actions against Apartheid South Africa, the ILWU refused to handle coffee from El Salvador due to the coffee plantation owners interference in the Salvadoran peace process.35

Aftermath

In 1995 John Sweeney won the Presidency of the AFL-CIO over establishment candidate Thomas Donahughe. Sweeney and the SEIU had been proud members of the NLC and fought against the pro-Cold War resolutions at AFL-CIO conventions. His victory was considered an enormous upset, as Donahue had been the protégé of Lane Kirkland. One sign of a shift in optics was that the AIFLD was renamed American Center for International Solidarity (ACILS) or Solidarity Center in 1997, at the suggestion of an Argentinean trade unionist who said that the old name conjured up bad memories for many Latin American union activists. Rename aside, however, the new organization continued to be a major recipient of money from the United States government through the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), an operation funded by the American State Department.

In 2000, there also appeared a move towards forcing the AFL-CIO to “come clean” about foreign activities of the union both past and present, including those in Latin America. A resolution was passed by the state AFL-CIO affiliates in California, Washington, and the national LGBTQ labor group Pride At Work that declared it was time to “fully account for what was done in Chile and other countries where similar roles may have been played in our name, to forever renounce such policies and practices and to openly invite concerned union members and researchers to review and discuss all AFL-CIO archives on international labor affairs.”36 San Jose Plumbers and Fitters Local 393 described the effort as trying to “own up to the past and divorce ourselves from those actions and the government funding which made us a pawn of US foreign policy.”

This effort, however, was not successful at the national AFL-CIO level, another sign of the difficulty in forcing meaningful change. Many unions that had previously supported pro-Cold War policies, such as the building trades unions and the American Federation of Teachers, were understandably not eager to have a full account made of Cold War activities that had overthrown democracies abroad. In lieu of passing the resolution, a meeting was brokered between supporters of the resolution and the AFL-CIO leadership, a very disappointing outcome for the activists involved in drafting and supporting the resolution.37

A disturbing continuation of the federation’s Cold War foreign policy can be seen in the AFL-CIO’s approach to Venezuela. In 2002, there was a coup attempt against then-President Hugo Chavez led by elements of the economic elite within the country. Chavez had been legitimately elected in elections in both 1998 and 2002 and this coup to overthrow a popularly elected leader was reminiscent of what had previously happened to Arbenz, Goulart, and Allende. One of the organizations important in setting up the anti-Chavez coup was the Confederation of Venezuelan Workers (CTV). The CTV was widely regarded as a pro-business “company union.” Its leader Carlos Ortega was closely associated with Pedro Carmona Estranga, the wealthy businessman who briefly took over from Chavez when the coup was attempted. The former AIFLD also contributed extensively to the union. From 1997 to 2001 the Solidarity Center received $587,926 from both USAID and the NED for the express purpose of working with the CTV in its efforts.38 After the coup attempt, Samuel Gaceck, a leading official in the AFL-CIO stated that the organization did “…condemn any and all coups and unilateral seizures of power which destroy and undermine democratic institutions, including in Venezuela.”39 However, the Solidarity Center continued to fund anti-Chavez groups after the coup attempt, in an effort to bring down Chavez’s government.40

It is clear that the AFL-CIO’s foreign policy has played a negative role in the development of trade unions in Latin America. Despite protestations of standing for workers rights and democracy, the federation’s foreign policy arm supported movements that were anti-labor and dictatorial in their aspirations. A full accounting is necessary on the AFL-CIO’s foreign policy activities as is an end to the receipt of funds from the CIA and the State Department. Workers the world over need an American labor movement that believes in solidarity forever, not solidarity sometimes.

- Simon Rodberg “The CIO Without the CIA” the American Prospect (December 19, 2001) http://prospect.org/article/cio-without-cia.

- Ronald Radosh American Labor and United States Foreign Policy (New York: Random House, 1969) 387.

- Charles Walker “Latin American Cloak and Daggers” Socialist Action (May 1, 2002) https://socialistaction.org/2002/05/01/latin-american-cloak-daggers-the-afl-cio-and-the-cia/.

- Ibid.

- Harry Kelber “AFL-CIO’s Dark Past: US Labor Reps Conspired to Overthrow Elected Governments in Latin America” the Labor Educator (November 29, 2004) http://www.laboreducator.org/darkpast4.htm.

- George Morris CIA and American Labor: the Subversion of the AFL-CIO’s Foreign Policy (New York: International Publishers, 1966) 83.

- Radosh 388-389.

- Kelber.

- Ibid.

- Fred Hirsch An Analysis of Our AFL-CIO Role in Latin America or Under the Covers With the CIA (San Jose: Fred Hirsch, 1974) 8-9; Kelber.

- Carmen Reed “AFL-CIO Dues Pay: A School For Scabs” Workers Power (March 13-26, 1975) https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/workerspower/wp116.pdf.

- Jeff Schruke “Reckoning With the AFL-CIO’s Imperialist History” Jacobin (Jan 9, 2020) https://jacobin.com/2020/01/afl-cio-cold-war-imperialism-solidarity.

- Morris 94.

- Ibid, 94-95.

- Beth Sims Workers of the World Undermined: American Labor’s Role in Foreign Policy (Boston: South End Press, 1992) 7.

- Morris 6.

- Carl Gershman Foreign Policy of American Labor (Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1975) 58.

- Tim Shorrock “Labor’s Cold War” the Nation (May 1, 2003) https://www.thenation.com/article/labors-cold-war/.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Herb Mills “Dockers Stop Arms to Pinochet” Social Policy Vol 35 (No. 4) (Summer, 2005) 24-28 http://www.ilwu10hmills.com/pdfs/Article11.pdf.

- Hobert A. Spalding “The Two Latin American Foreign Policies of the U.S. Labor Movement: The AFL-CIO Top Brass vs. Rank-and-File” Science & Society Vol. 56 (No. 4) (Winter, 1992) 422.

- Sims, 82-83.

- Spalding, 427-428.

- Rodberg.

- Spalding, 431.

- Andrew Batista “Unions and Cold War Foreign Policy in the 1980s: The National Labor Committee, the AFL-CIO, and Central America” Diplomatic History Vol 26 (No. 3) (December 17, 2002) 445-446.

- Spalding, 434.

- Alan Benjamin “AFL-CIO Leaders Launch Drive to Counter Antiwar Mood in Unions” Socialist Action (November 1985) https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/socialistaction/v03n11-nov-1985-socialist-action.pdf.

- Battista 423.

- Daniel Cantor and Juliet Schor Tunnel Vision: Labor, the World Economy, and Latin America (Boston: South End Press, 1987) 11.

- Ibid, 3.

- Mark Carlson “Debate on Central America Jolts AFL-CIO Convention” Socialist Action (December 1985) https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/socialistaction/v03n12-dec-1985-socialist-action.pdf.

- Battista 431.

- “Longshoremen Threaten to Widen Salvadoran Boycott” United Press International (April 19, 1991) https://www.upi.com/Archives/1991/04/19/Longshoremen-threaten-to-widen-Salvadoran-boycott/5484672033600/.

- Kim Scipes “California AFL-CIO Repukes Labor’s National Level Foreign Policy Leaders” Labor Notes (August 31, 2004) https://labornotes.org/2004/08/california-afl-cio-rebukes-labor%E2%80%99s-national-level-foreign-policy-leaders; Pride At Work “It’s Time To Clear the Air About the AFL-CIO” Pride At Work (June 24, 2000) https://www.prideatwork.org/its-time-to-clear-the-air-about-the-afl-cio/.

- Kim Scipes “AFL-CIO Refuses to ‘Clear the Air’ on Foreign Policy Operations” Labor Notes (February 1, 2004) https://www.labornotes.org/2004/02/afl-cio-refuses-%E2%80%9Cclear-air%E2%80%9D-foreign-policy-operations.

- Kim Scipes “AFL-CIO in Venezuela: Deja Vu All Over Again” Labor Notes (April 1, 2004) https://labornotes.org/2004/04/afl-cio-venezuela-d%C3%A9j%C3%A0-vu-all-over-again.

- Lee Sustar “Is This the Return of the AFL-CIA?” Socialist Worker (May 17, 2002) https://socialistworker.org/2002-1/407/407_11_AFLCIA.php.

- Tim Gill “Newly Revealed Documents Show How the AFL-CIO Aided US Interference in Venezuela” Jacobin (August 5, 2020) https://jacobin.com/2020/08/venezuela-hugo-chavez-afl-cio-united-states.