Since the proletariat must first of all acquire political supremacy, must rise to be the leading class of the nation, must constitute itself the nation, it is, so far, itself national, though not in the bourgeois sense of the word.“Though not in substance, yet in form, the struggle of the proletariat with the bourgeoisie is at first a national struggle. The proletariat of each country must, of course, first of all settle matters with its own bourgeoisie.

Both from the Communist Manifesto

I come to this platform tonight to make a passionate plea to my beloved nation. This speech is not addressed to Hanoi or to the National Liberation Front. It is not addressed to China or to Russia…. I knew that I could never again raise my voice against…violence…without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today—my own government.

Martin Luther King, Jr., Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence

After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, it seemed the Cold War and Big Power conflicts were over. Capitalism had triumphed, both Russia and China had entered the world market system, and the End of History was proclaimed. The fight against exploitation and imperialism continued, but the main terms of debate shifted away from the prospect of military confrontation between major powers to the economic analysis of neoliberalism, globalization, and surplus extraction. Then the Russian invasion of Ukraine occurred, suddenly catapulting the old problem of Big Power conflict back to the center of world politics.

For most of the twentieth century, Marxists relied on the Leninist theory of imperialism and revolutionary defeatism to deal with this issue. Matthew Strupp outlined one interpretation of this theory in a Cosmonaut article[1] two years ago, and more recently he and Alexander Gallus have argued that this theory is applicable to the war in Ukraine.[2] Strupp’s first article is a capsule summary of the longer and much more elaborate argument developed by Mike Macnair in his Revolutionary Strategy, which takes issue with Hal Draper’s detailed study, The Myth of Lenin's "Revolutionary Defeatism". I’ll have more to say about this theory and its interpretation by these authors later, but I want to preface that discussion with a review of the history of the Cold War and opposition to it in the US from the atomic bombing of Japan to the Vietnam War. I have four reasons for starting there:

1) Size and Power: No empire in history was as powerful or far-reaching as the US in the early years of the Cold War. After WWII, the US possessed two-thirds of the world’s industrial capacity and enjoyed military supremacy across the globe, excepting only that part controlled by the Soviet army. The Soviet Union, though large in area, was incapable of anything more than defending the boundaries of this area and posed no military threat to the US itself. The US alone possessed the capacity for global strategic initiative. It is always dangerous to bring up the example of Hitler, but the rise of fascism had confronted Marxists with the question of whether some imperialisms are worse than others and whether Lenin’s theory of revolutionary defeatism was adequate to deal with such a problem. The extraordinary dominance of the US after WWII posed a similar problem. Although the relative strength of the US has declined, its absolute power still greatly surpasses all others. Is US power now just a difference of degree or is it still a difference in kind?

2) Geographical Impregnability: Unlike the nation-states of Europe, the US was and is invulnerable to conventional invasion and occupation. The only possible military threat to US national survival is nuclear, a weapon the US itself was the first to create and use with full knowledge that the Soviet Union also had the capacity to develop its own nuclear arsenal. In terms of conventional military thinking about national security, the US should never have used the Bomb on Japan and should have proceeded immediately after the defeat of Germany to seek a comprehensive system of mutual nuclear inspections and disarmament with the Soviet Union. It did the opposite and initiated a nuclear arms race that still threatens its own and the world’s survival. It traded the risk of future nuclear catastrophe for greater immediate leverage in the construction of a world empire;

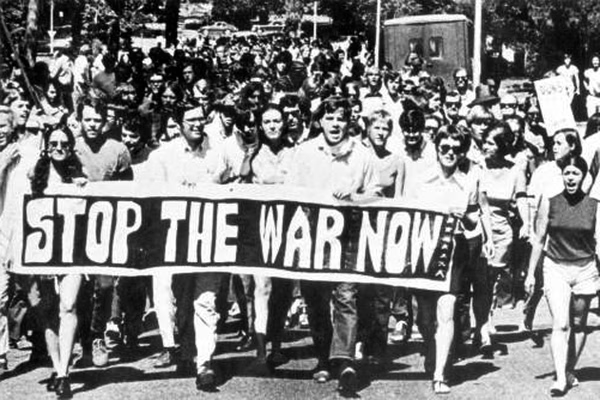

3) Opposition to US Imperialism: Although the emergence of an anti-Cold War, anti-imperialist US left after WWII was slow and difficult, it wasn’t complicated. The US had so obviously started the nuclear arms race and sided with former colonial powers in putting down demands for national independence that the issues were clear-cut. This was despite the continuing Soviet occupation and repression of reform efforts in Eastern Europe. The character of the anti-imperialist movement in the US from 1945-70 was essentially the same as that sketched in the quotations from Marx and King above: the primary aim was to force our own government to end its interventions in former colonies and its aggressive military buildup throughout the world as a whole.

In recent discussions of Ukraine, I have argued that the Russian invasion is similar to the Soviet Union’s invasions of Hungary and Czechoslovakia in 1956 and 1968, that the left in the US has no power to do anything about it, and that our main political focus should still be opposition to US imperialism. The countries of Eastern Europe in the 1950s and ‘60s certainly had as much right to national independence as Ukraine does now, but there was no feasible way for that right to be realized other than through a NATO invasion. The right of the nations of eastern Europe to self-determination was in conflict with the right of the people in other countries to oppose a military escalation that might trigger WWIII. How to decide between these conflicting rights and interests? Do the citizens of NATO countries now think it is reasonable to risk a wider war with Russia by supplying arms and training to the Ukrainian government? Should the US left go along with this brinksmanship? Is the Ukrainian government even an independent power any longer or has NATO essentially taken over through its funding, training, and supervision of Ukraine’s military, police, and intelligence services? If defeating Russian aggression is so crucial to the survival of freedom and democracy, why shouldn’t NATO fight the Russians directly? One response I received to these questions was that Marx’s concession to national forms of the class struggle had paved the way for Stalin’s theory of socialism in one country and that Trotsky was right: the class struggle has to be waged by a unified international proletarian party and army on a world scale (the International Brigades of the Spanish Civil War writ large), Ukraine now being the site where the world’s revolutionary forces should concentrate their efforts, NATO arms and all. Another slightly less war-like response granted that the capacity of US leftists to have any influence on the war in Ukraine was virtually nonexistent, but that a principle was at stake and that any doubts about the effectiveness of condemning Putin or expressing support for Ukrainian independence constituted a retreat from revolutionary internationalism into insular nationalist reformism.

Of course, I didn’t think I was being unprincipled or reformist, but I couldn’t immediately express clearly what my principles were in the language of Marxist internationalism. What we did in the 1960s out of simple moral impulse with little knowledge of Marxism or regard for Soviet operations in Eastern Europe now demanded a more systematic explanation. My starting point was to clarify what I saw as the main weakness in the above responses: the almost complete lack of any connection between principle and political effectiveness, whether that effectiveness involved the prospect of forming an independent Marxist political and military force within Ukraine itself or of influencing Russian actions by repeated denunciations of Putin.

As the invocation of the ghosts of Stalin and Trotsky indicates, the arguments in these responses have deep historical roots in Trotsky’s criticism of Stalin’s Popular Front policies in the 1920s and ‘30s, which did in fact sacrifice working class political independence and internationalist principles for narrow nationalist ends. The mistake is to think these are the only two strategic choices available to the left. They are not, and that is what an evaluation of the anti-imperialist movement in the US during the height of the Cold War can establish.

4) Back to the Future: A peculiarity of US anti-imperialism in the immediate post-WWII period is that it wasn’t Marxist or socialist in theory or in name, even though it had roots that stretched back to the pre-WWI Socialist Party. That old socialist movement had been pulled apart post-WWI first by Bolshevism to its left and then on the right by the New Deal and the seeming necessity to fall in behind Roosevelt in the fight against fascism. Only after the war in response to the Bomb, the Cold War, and neocolonialism did an anti-war and anti-imperialist movement independent of the Democratic Party re-emerge. Eventually, this movement came to be called a New Left in order to distinguish it from the remnants of an Old Left whose identities were still bound up with the multiple Socialist-Stalinist-Trotskyist disputes of the 1920s and ‘30s.

In order to draw out the political implications of New Left anti-imperialism, I’m going to draw the distinction between pure and practical ideology that Franz Schurmann employed in his classic study of Chinese Communism.[3] This distinction is not the same as either the difference between strategy and tactics or between a minimum and maximum program. In the distinction between pure and practical ideology, the dividing line is drawn at a higher level to emphasize that prescriptions for practical political action cannot be deduced directly from the general principles of an ideology itself. The world is far too complicated for that. Between general ideology and practice, there is an irreducible indeterminacy requiring political judgment. In the case of Marxism, along with the overarching general theory of historical change through the development of productive forces, class struggle, capitalist crises, and socialist revolution, Marxists have also had to contend with a multitude of complicating factors handed down from history such as racial, ethnic, and religious differences within a country; the domination and exploitation of one country by another; and different levels of economic and political development between countries. But the greatest force working in opposition to a Marxist class ideology has been the ability of multiple powerful nation-states to enlist their working classes in wars against each other. Marx’s acknowledgment in the Manifesto that the workers’ struggle must first be national in form, even though the capitalist market is global in scope and a world without borders is the ultimate aim of the workers’ movement, involved the recognition that individual working classes had already become too deeply entangled in the economic and political life of their own countries to act directly and immediately as a single, unified international class. Marx concluded from this observation that each national working class would first have to fight for power in its own nation. As he put it in the Manifesto, “the first step in the revolution by the working class is to raise itself to the position of ruling class, to win the battle of democracy.”

By “win the battle of democracy,” Marx meant democracy as it had been understood since the American and French Revolutions: a single representative assembly elected by universal, equal, and direct suffrage. That is what Marx and Engels learned from the Chartists, what they fought for in 1848, what they meant by the dictatorship of the proletariat, and also what their followers meant until 1917, as the historical work of Hal Draper, Richard N. Hunt, and Neil Harding established in the 1960s and ‘70s and which August Nimtz and Lars Lih have added to more recently. Of course, in 1917 and the years immediately following, the Bolsheviks proposed the idea that workers’ councils and then the single-party dictatorship constituted new and higher forms of working-class democracy. In the Bolsheviks’ new theoretical framework, the old Marxist goal of a democratic republic was downgraded to just another species of “bourgeois democracy,” a literal oxymoron that had previously been used mainly as an offhand rhetorical equivalent for the analytically more accurate “liberal or bourgeois republic,” “liberal or bourgeois parliamentarism,” or “liberal or bourgeois constitutionalism.” Since our own constitutional system is an undemocratic liberal republic and not a democratic republic, these distinctions still matter for us.

Although the New Left never got as far as challenging the Constitution directly, it got close. Tom Hayden, in his notes and draft for what became The Port Huron Statement, saw that James Madison’s constitutional philosophy and design was anti-democratic to its core, but any hint of this insight was dropped from the final Statement.[4] And Martin Luther King certainly possessed the historical and political imagination to see that the Civil Rights Movement shared much in common with other great historical movements for democracy:

America’s third revolution—the Negro revolution—had begun.[In 1963] For the first time in the long and turbulent history of the nation, almost one thousand cities were engulfed in civil turmoil, with violence trembling just below the surface. Reminiscent of the French Revolution of 1789, the streets had become a battleground, just as they had become the battleground, in the 1830s, of England’s tumultuous Chartist movement. As in those two revolutions, a submerged social group, propelled by a burning need for justice, lifting itself with sudden swiftness, moving with determination and a majestic scorn for risk and danger, created an uprising so powerful that it shook a huge society from its comfortable base.[5]

We can't know with any certainty how King’s political philosophy and strategy would have developed if he had not been murdered, but we don’t have to. Because King’s work had already transformed American society so profoundly, and because his compassion for the oppressed across the world had already been expressed so clearly, the essential shape of a new form of politics in the US had already been drawn in outline. On the level of pure theology/morality/ideology, King was an apostle of love and justice for all humanity. By joining the struggle for human dignity and freedom in the American South, King had set out on a life-long search for a way to make his ideals a living reality.

If we compare King’s politics and the movement he symbolized to the statements of the arms-for-Ukraine proponents mentioned above, they differ in several fundamental ways. First, neither King nor the New Left in general were coalitionist or nationalist. They broke decisively with the Democratic Party on both domestic and foreign policy. So, in addition to the proffered political binary of revolutionary international socialism vs. nationalist reformist coalitionism, we have to add a third category of radical democratic anti-imperialism. To be a complete and coherent ideology of its own, this democratic anti-imperialism would have to be expanded into a full democratic republicanism with the goal of replacing the existing US constitutional order, but the political independence of King and the New Left from the Democratic Party is plain enough to make the point. Second, at their extremes, both the Third International and the Trotskyist Fourth International(s) envisioned the working class acting in unison across national boundaries under the leadership of a single revolutionary organization. Some of their progeny still do. Originally, there was good reason to think this might be possible: the distance from Paris to St. Petersburg is about the same as that from New York to Kansas City, but in Europe roughly a dozen states or nationally coherent peoples are crammed into that space. Such close proximity naturally led working-class movements to try to overcome national divisions by aiding each other directly. In the end, however, the nation-state and nationalism proved stronger. Trotsky’s own formula of combined and uneven development provides a clue as to why: the unevenness of development, including the existence of nation-states, militates against direct international combination. Nationalism will not be overcome by the formation of international brigades, be they Lincoln Brigades, Venceremos Brigades, or Ukraine Brigades. It will only be overcome when nation-states are prevented by their own populations from pursuing nationalist policies. Third, King’s life’s work illustrates how a commitment to the values of universal justice can be expressed through opposition to one’s own government’s policies. It was, first of all, King’s participation in the Civil Rights Movement that gave his words their unique moral authority. He sympathized with the oppressed everywhere, making no exception for communist regimes, but he saw at the same time how the US twisted the crimes of others into excuses to commit crimes of its own, as if “this one’s shame deposits in that one’s account the right to shamelessness.”[6] Faced with these multiple centers of immoral power in conflict with one another, King would not submit to his own government’s moral blackmail and was able to cut through both the Cold War propaganda of a world-wide Communist conspiracy and the narrower Munich-inspired myth of a pathologically expansionist Soviet empire in order to oppose his own country’s malevolence.

Because I think the Russian invasion of Ukraine is in the same rough category as the USSR’s invasion of Hungary and Czechoslovakia, and because I don’t think Russia has either the capacity or intention to advance much farther, I think King’s stand against US military intervention in Vietnam and throughout the world corresponds closely with the stand we should take regarding Ukraine. This stand is no more a defense of Putin’s actions than King’s stand was a defense of the USSR. Nor is it a denial of Ukraine’s right to independence. The one possible objection to drawing this parallel between King and Vietnam and ourselves and Ukraine is that Ukraine, like Vietnam and unlike Hungary and Czechoslovakia, is in a position to receive some arms without immediately risking a direct confrontation between NATO and Russia. My judgement on that score is that NATO itself does not desire an all-out war with Russia and will therefore limit what it supplies to Ukraine; but this scenario is a trap for the Ukrainians that will result in the destruction of their country, something that has been in the cards of the cynical game the US has been playing since the beginning of the Cold War. Of course, this military assessment could be wrong. NATO might turn more aggressive or make a mistake and fuel a wider war, the result of which could trigger the use of nuclear weapons. Or Ukraine and NATO might prevail, Putin might fall, Russia might break apart, and we might end up in a new geopolitical world. It has happened before. But none of these possible scenarios can justify NATO arms for Ukraine. The risks far outweigh any likely benefits.

Finally, many in the US who oppose supplying arms to Ukraine use the phrase “the main enemy is at home.” Supporters of arms for Ukraine say this phrase represents the substitution of national reformist political goals for revolutionary internationalist goals. I’ve already said this binary does not recognize the possibility of a strategy of democratic transformation in the US and the assertion of internationalist principles through opposition to the US empire. King had internationalist, democratic, humanitarian principles that he expressed primarily “at home.” But where else could he have expressed them? What weight would King’s words have carried if he had moved to Paris or Stockholm? Physically, culturally, and politically, where else can any of us express our principles except “at home”? “Internationalist support” generally takes the form of pronouncements, articles, demonstrations, interviews, and panel discussions “at home,” with maybe an international conference in another country now and then. Only a tiny few actually raise money or travel to other countries to participate in struggles there, activities that are incapable of forming the basis for a mass political party here. So, “home” isn’t really a designation of where we try to put our principles into practice but a proxy for how we put them into practice, a proxy for how we transform the pure ideology/morality of world-wide human emancipation into a practical ideology of strategy and tactics. In the long history of socialist thinking, strategic and tactical proposals have followed one of three main paths: reformism, democratic republicanism, or the trans-national strategies deriving from the revolutionary periods of the Third and Fourth Internationals. Until fairly recently, the historical memory of democratic republicanism had faded so much that it had been virtually forgotten as a possible independent strategy of its own. But that is now changing, and that change allows us to specify more clearly where the strategic and tactical flaws in Third and especially Fourth International socialism lie: This conception of internationalism places the final goal of the abolition of capitalism and the nation-state at the center of its mass political agitation. Strategy and tactics in this conception simply are advocacy for this final goal. This form of thinking puts the original Marxist strategic goal of conquering state power through the establishment of a democratic republic in the category of nationalist bourgeois reformism and treats the democratic republic as just another form of bourgeois liberalism. The opposite is the case: the fight for a democratic republic in the US is the practical strategic implementation of revolutionary proletarian internationalist principles.

King, Black Power, and Revolutionary Defeatism

The democratic republican internationalism that I have extrapolated from King’s stand against the Vietnam War and his campaigns for civil, political, and economic rights overlaps to a significant degree with the revolutionary defeatist position that “the main enemy is at home”; but these two positions are not identical, are not derived from the same principles, and employ different vocabularies and slogans. Do these differences matter? I think they do.

The best introduction to these issues as I see them is King’s discussion of the Black Power slogan in Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?[7] (All following quotations in this section from this source with page numbers.) The background to this discussion is that in 1966 King, Stokely Carmichael, and other Black leaders had gathered in Mississippi to continue James Meredith’s March Against Fear after Meredith had been shot by a sniper. Carmichael chose this setting to put forward the slogan of Black Power as an alternative to the traditional civil rights slogans of Freedom Now and Black and White Together favored by King. The issues raised were difficult and complex and, in King’s eyes, posed choices of racial separation vs. multi-racial politics; emotional frustration vs. strategic calculation; violence vs. nonviolence as strategic orientations; American identity vs. African identity as primary; and Third World-ism vs. a strategy of transforming US politics and government from within. Not all of the issues in King’s discussion of Black Power track in a one-to-one correspondence to the issues raised in the theory and slogan of revolutionary defeatism, but there are enough similarities to make the comparison useful.

King begins his consideration of the Black Power slogan with the assumption that both he and Carmichael share the same goal, but that Black Power involved “an unfortunate choice of words.” (p. 39):

It was my contention that a leader has to be concerned about the problem of semantics. Each word, I said, has a denotative meaning—its explicit and recognized sense—and a connotative meaning—its suggestive sense. While the concept of legitimate Black Power might be denotatively sound, the slogan ’Black Power’ carried the wrong connotations. I mentioned the implication of violence that the press had already attached to the phrase. And I went on to say some of the rash statements on the part of some of the marchers only reinforced that impression. (p. 30)Stokely replied by saying that the question of violence versus nonviolence was irrelevant. The real question was the need for black people to consolidate their political and economic resources to achieve power. ‘Power,’ he said, ‘is the only thing respected in this world, and we must get it at any cost.’ Then he looked me squarely in the eye and said, ‘Martin, you know as well as I do that practically every other ethnic group in America has done just this. The Jews, the Irish and the Italians did it. Why can’t we? (p. 30)

‘That is just the point,’ I answered, ‘No one has ever heard the Jews publicly chant a slogan of Jewish power, but they have power. Through group unity, determination and creative endeavor, they have gained it. The same thing is true of the Irish and Italians. Neither group has used a slogan of Irish or Italian power, but they have worked hard to achieve it. This is exactly what we must do,’ I said. (p. 30-1)

King then grants that the Black Power slogan was a response to the very real problem of how black people should best organize themselves so as not to be overwhelmed by the well-intentioned but sometimes smothering involvement of white supporters, and he also grants that the slogan embodied a powerful and much needed assertion of black pride and independence:

Nevertheless, in spite of the positive aspects of Black Power, which are compatible with what we have sought to do in the civil rights movement all along without the slogan, its negative values, I believe, prevent it from having the substance and program to become the basic strategy of the civil rights movement in the days ahead. (p.44)Beneath all the satisfaction of a gratifying slogan, Black Power is a nihilistic philosophy born out of the conviction that the Negro can’t win. It is, at bottom, the view that American society is so hopelessly corrupt and enmeshed in evil that there is no possibility of salvation from within. Although this thinking is understandable as a response to a white power structure that never completely committed itself to true equality for the Negro, and a die-hard mentality that sought to shut all windows and doors against the winds of change, it nonetheless carries the seeds of its own doom…. (p. 44)

Who are we? We are the descendants of slaves. We are the offspring of noble men and women who were kidnapped from their native land and chained in ships like beasts. We are the heirs of a great and exploited continent known as Africa. We are the heirs of a past of rope, fire and murder. I for one am not ashamed of this past. My shame is for those who became so inhuman that they could inflict this torture upon us. (p. 53)

But we are also Americans. Abused and scorned though we may be, our destiny is tied up with the destiny of America. In spite of the psychological appeals of identification with Africa, the Negro must face the fact that America is now his home, a home he helped build through ‘blood, sweat and tears.’ Since we are Americans the solution to our problem will not come through seeking to build a separate black nation within a nation, but by finding that creative minority of the concerned from within the ofttimes apathetic majority, and together moving toward that colorless power that we all need for security and justice. (p. 54)

In the first century B.C., Cicero said: ‘Freedom is participation in power.’ Negroes should never want all power because they would deprive others of their freedom. By the same token, Negroes can never be content without participation in power. America must be a nation in which its multi-racial people are partners in power. This is the essence of democracy toward which all Negro struggles have been directed since the distant past when he was transplanted here in chains…. (p. 54)

Arguments that the American Negro is a part of a world which is two-thirds colored and that there will come a day when the oppressed people of color will violently rise together to throw off the yoke of white oppression are beyond the realm of serious discussion. There is no colored nation, including China, that now shows even the potential of leading a violent revolution of color in any international proportions. Ghana, Zambia, Tanganyika and Nigeria are so busy fighting their own battles against poverty, illiteracy and the subversive influence of neocolonialism that they offer little hope to Angola, Southern Rhodesia and South Africa, much less to the American Negro. The hard cold facts today indicate that the hope of the people of color in the world may well rest on the American Negro and his ability to reform the structure of racist imperialism from within and thereby turn the technology and wealth of the West to the task of liberating the world from want. (p. 57)

I admit my bias. I agree with King’s strategic analysis of power relations in the US and internationally and his moral and ideological commitment to multi-racial democracy. The tragedy is that King was cut down and prevented from carrying out this mission. Some in the movement then chose to continue on a nationalist or separatist path, while others attempted to forge a multi-racial alliance more along the lines suggested by King. In my own small part in these events, I was a member of the Revolutionary Union and was overjoyed when the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization, the Black Workers Congress, and I Wor Kuen agreed to set up a National Liaison Committee in mid-1972 with the RU. Combined with the RU’s important role in supporting the 4,000 mainly Mexican-American workers on strike against the Farah Pants Company in El Paso, it seemed like a radical, anti-imperialist, multi-racial working class movement and organization was actually coming into being. The reasons why this effort fell apart are too complicated to go into here, but the short explanation is that the groups involved, particularly the RU, ceased to see themselves as continuing on the democratic path originally charted out by the Civil Rights/New Left movements and shifted decisively in the direction of Marxism-Leninism and a warmed over Stalinism.

It is important to keep in perspective just how much the Civil Rights Movement did accomplish. In answer to the complaint “that the Negro has made no progress in a decade of turbulent effort,” King points out:

The South was the stronghold of racism…. Prejudice, discrimination and bigotry had been intricately embedded in all institutions of southern life, political, social and economic. There could be no possibility of life-transforming change anywhere so long as the vast and solid influence of southern segregation remained unchallenged and unhurt. The ten-year assault at the roots was fundamental to undermining the system. What distinguished this period from all preceding decades was that it constituted the first formal frontal attack on racism at its heart. (p. 13)Since before the Civil War, the alliance of southern racism and northern reaction has been the major roadblock to all social advancement. The cohesive political structure of the South working through this alliance enabled a minority of the population to imprint its ideology on the nation’s laws. This explains why the United States is still far behind European nations in all forms of social legislation. England, France, Germany, Sweden, all distinctly less wealthy than us, provide more security relatively for their people. (p. 14)

Hence in attacking southern racism the Negro has already benefitted not only himself but the nation as a whole. Until the disproportionate political power of the reactionary South in Congress is ended, progress in the United States will always be fitful and uncertain. (p. 14)

King is describing the Second Reconstruction, the struggle by which the African-American people, in finally attaining equal civil and political rights within the framework of the existing Constitution, was also simultaneously breaking up the old regionally-based US political party system and forcing it to reorganize along national lines. W. E. B. Du Bois had argued in Black Reconstruction that black workers were the leading force for democracy in the US. He may have been off in his timing by about a century, but he was right in the end. Conditions were not favorable during the First Reconstruction for the newly free to find durable allies and supporters, but things had changed by the 1950s. King was under no illusion at the time of his death that the civil and political rights that had been won were enough by themselves to constitute true human freedom and equality. He was very much aware that the struggle had passed beyond the realm of the existing Constitution and that the establishment of collective economic rights required that it be changed (p. 130). That is where we have been stuck for more than fifty years.

The Similarities Between the Black Power and Revolutionary Defeatism Slogans

Many of the weaknesses that King saw in the Black Power slogan also afflict the slogan of revolutionary defeatism, but to get at those similarities we first have to clarify what the revolutionary defeatism slogan is supposed to mean. Unlike the Black Power slogan, which was the product of a well-thought-out plan executed in familiar and clearly understood political circumstances, Lenin’s revolutionary defeatism slogan originated as a rushed response to the sudden outbreak of a war involving all the major states of Europe. In addition, even though Lenin continued to use the words “revolutionary defeatism” to describe his policies for more than two years during the war, the policies that those words were used to represent continued to mutate. Hal Draper has done the most to clarify the different meanings and implications of this shifting terminology over time, and I believe his analysis is sound. As Draper emphasizes, Lenin (or his close associate Zinoviev) included five different aspects of an anti-imperialist policy under the term “revolutionary defeatism” at different times: a wish for the military defeat of the Russian government, a wish for the military defeat of all imperialist governments, to turn the imperialist war into a civil war, to carry out anti-war agitation within the military, and to split from the Second International and form a new one. Draper thinks the revolutionary defeatism slogan itself and the “wish for defeat” aspects of it were frantic and confused overreactions that were unworkable as practical political slogans, and he also thinks they are completely detachable from the other three aspects of a coherent anti-imperialist policy. And, as a last point, he maintains that Lenin himself abandoned the slogan of revolutionary defeatism when it really mattered after he made it back to Russia in April 1917. Macnair, on the other hand, thinks Draper’s analysis is wrong and that the slogan and concept of revolutionary defeatism remain indispensable.

Instead of beginning with a dissection of the origins and evolution of the revolutionary defeatism slogan during WWI, I am going to start with the example of a war much closer in time to our own: the Vietnam War. It is best to start there because both Macnair and Strupp hold up the Vietnam War as the best recent illustration of the strategy of revolutionary defeatism. By seeing how they apply the concept to a war much more limited in scope than WWI, we can narrow down what the core concept of revolutionary defeatism means for them. From there we can work back to the much more complex and confusing debates of WWI.

Macnair (Strupp’s account is essentially the same) frames his interpretation of the anti- Vietnam War movement within what he takes to be the two essential features of Lenin’s revolutionary defeatist policy (All quotations in this section and the next are from Macnair’s Revolutionary Strategy.):

The first is that the primary political context is Lenin’s argument for a clear split in the International….(p. 71)The second is the concrete conclusion which follows from defeatism. That is, that socialists should, so far as they are able, carry on anti-war agitation in the ranks of the armed forces…. In November 1914 Lenin wrote: …’It is the duty of every socialist to conduct propaganda of the class struggle in the army as well; work directed towards turning a war of the nations into civil war is the only socialist activity in the era of an imperialist armed conflict of the bourgeoisie of all nations.’ (p. 71)

Macnair then claims the second part of this policy was at work in the US anti-Vietnam War movement:

To carry on an effective agitation against the war in the ranks of the armed forces is, unavoidably, to undermine their discipline and willingness to fight. This was apparent in 1917 itself. It is confirmed by subsequent history. One of the few effective anti-war movements in recent history was the movement against the Vietnam War. If we ask why this movement was successful, the answer is clear: it did not merely carry on political opposition to the war (demonstrations, etc.) but also disrupted recruitment to the US armed forces and organized opposition to the war within the armed forces. The result— together with the armed resistance of the Vietnamese—was a US defeat. (p. 72, Emphases in original.)

Macnair then moves from the Vietnam example and reiterates his interpretation of Lenin’s general theory:

Lenin’s defeatism was arguing for two fundamental changes in the strategy of international socialism. The first was a clear split: the abandonment of the historic policy of unity of the movement at all costs which had flowed from the success of the Gotha unification, the SPD and the unifications which it had promoted. (p. 72)The second was a new strategic policy in relation to war, or, more exactly, in relation to imperialist wars. This policy called for an open proclamation along the lines that ‘the main enemy is at home’, to ‘turn the imperialist war into a civil war’, and complementing this, practical efforts to undermine military discipline by anti-war agitation and organizing in the armed forces. (p. 73)

Finally, Macnair characterizes Draper’s position as follows:

Draper’s view is that the defeat slogan is simply wrong—meaningless unless you positively wish for the victory of the other side. It must follow that unless you support such a scenario, you would not go beyond a slogan along the lines of ‘Carry on the class struggle in spite of the war’. That is, you would not arrive at Lenin’s argument that the principal way to carry on the class struggle in such a war is to argue that civil war is better than this war and to undermine military discipline by anti-war agitation and organization in the armed forces. (p. 73, Emphases in original.)

In his short comments on the Vietnam War, Macnair says nothing about the actual slogans the US anti-war movement used in its literature. He simply observes that the US was defeated in Vietnam and attributes that defeat, at least in part, to anti-war agitation within the armed forces. From these two facts he then infers that the US anti-war movement followed a policy of revolutionary defeatism. However, just to be clear, the fact of US military defeat in Vietnam isn’t essential to Macnair’s main argument. His main argument is simply that an essential part of Lenin’s revolutionary defeatism is that revolutionaries must carry out anti-war agitation among the troops no matter what. The Vietnam case is just a rare and convenient illustration of that policy seemingly carried out to a successful conclusion.

In order to judge the adequacy of Macnair’s characterization of the movement against the war in Vietnam, I’m going to compare it to some specific events surrounding the activities of the Fort Dix GI coffeehouse group in 1969. A longer account of these events can be found on pp. 3-8 of my essay, You Can't Use Weatherman To Show Which Way The Wind Blew, but the essentials are as follows: The coffeehouse group, which was made up of SDS members from the original Newark community organizing project, Princeton, Columbia and other New York City chapters, was planning to hold a rally at Fort Dix in September in support of thirty-eight soldiers who had been charged with a variety of crimes stemming from a riot in the base’s prison in June. At the final planning meeting for the demonstration, members of Weatherman announced they planned to carry flags of the Vietnamese National Liberation Front and attack various parts of the base. The coffeehouse group and the majority at the meeting opposed Weatherman’s plans and the date of the demonstration was changed to mid-October to prevent Weatherman’s participation, because Weatherman had already made plans to be in Chicago that week. Instead of NLF flags and Weatherman’s slogan of “bring the war home,” the demands of the demonstration were: 1) Free the Fort Dix 38, 2) Free all political prisoners, especially the Panthers, 3) Abolish the stockade (prison) system, and 4) End the war in Vietnam.

How do the words “revolutionary defeatism” fit with these events? They coincide most closely with Weatherman’s position on the war, which was literally a wish for US defeat and an NLF victory, and Weatherman expressed this wish explicitly in their slogans and by carrying NLF flags. They also literally saw themselves as a detachment of an international guerilla army that wanted to turn domestic opposition to the Vietnam war into a civil war in the US immediately. The overwhelming majority of SDS members and other supporters of the Fort Dix Thirty-Eight, including the Panthers, the Young Lords, and the Young Patriots, agreed that the main anti-war slogans should be something like “end the war,” “immediate withdrawal,” or “bring the troops home now.” Even if our sympathies were on the side of the Vietnamese and we had chanted “Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh, NLF Is Gonna Win” at mass demonstrations in New York or Washington, D. C, in the past, when it came down to a sober assessment of how to advance the anti-war movement most effectively and widen its reach to broader segments of the population, the slogan of End the War seemed best.

Let me interject at this point some of the parallels I see between the Black Power slogan and the revolutionary defeatism slogan. As King emphasized, words have both a denotative and connotative meaning. Both King and Carmichael wanted political power for black people, but they had different estimations of which words and strategies would be best suited to achieve that goal. Similarly, both Weatherman and the Fort Dix coffeehouse group wanted the US out of Vietnam, but disagreed about how to go about it and which slogans and symbols to use. It is particularly easy to see that Weatherman’s choice of slogans and strategy quickly led to political isolation and ineffectiveness. The strategies associated with Black Power were not so obviously isolating and ineffective as Weatherman’s, but there, too, there was a shift toward Third-Worldism, some attraction to a strategy of urban guerrilla warfare, and a strong disinclination to having anything to do with “white America.”

In his defense of revolutionary defeatism as a policy, it is not at all clear whether Macnair actually favors calling publicly for the defeat of one’s own government by another country in popular agitation and slogans. The positive political slogans he does cite are “the main enemy is at home” and “turn the imperialist war into a civil war,” and these slogans are supposed to provide the political guidance for the content of the anti-war agitation to be carried out within the armed forces, but he gives no indication what the specific content of that agitation is supposed to be. He points to the anti-war movement in the US as an example, but provides no evidence that the anti-war agitation within the military during the Vietnam War employed the slogans he cites or anything similar to them. This is a serious shortcoming in Macnair’s account. In addition, Macnair is too mechanical in his depiction of how the “movement” “disrupted” the draft and “organized” opposition within the armed forces. He writes as if the US anti-war movement was similar in structure to the socialist movement Lenin was writing about in WWI, something outside of and apart from the draftees and soldiers themselves, who were mostly peasants in WWI and not part of the normal pre-war socialist constituency. That was not the situation in the US in the 1960s. The main disruption of the military conscription process came not from any organized civilian part of the anti-war movement but from the million or so draftees who never showed up for induction in the first place, and from the many thousands more who later went AWOL, and the many others who eventually refused to fight. Similarly, most of the anti-war cartoons, flyers, and newspapers that circulated within the military were produced by the soldiers themselves, certainly in Vietnam itself but also probably on domestic US military bases as well. Soldiers did get some help from the coffeehouse movement and the very few radicals who purposely enlisted in order to organize, but overwhelmingly the anti-war movement within the military was self-organized and self-directed. Max Elbaum’s metaphor of “Revolution in the Air” is the best characterization of how anti-war sentiment was pervasive throughout the US, from SNCC, Malcolm X, and Muhammed Ali refusing induction into the army to rock and folk music, SDS, mass anti-war demonstrations, Ramparts Magazine, and underground newspapers. The “movement” didn’t have to bring anti-war agitation to the troops. The troops were already aware of it, produced it themselves, and were themselves part of the movement from the beginning. The challenge facing the left was how to develop a strategy that could unite all the scattered strands of this movement into a more coherent political force.

Macnair vs. Draper

The historical evidence from the US anti-Vietnam War movement does not support Macnair’s claim that it is an instance of a distinct revolutionary defeatist strategy. The anti-war movement did not in general use defeatist language, nor did it advocate anything like turning the imperialist war into a civil war. It did hold that the real enemy was at home, that imperialist wars must be opposed, and that anti-war literature should be distributed to soldiers and potential draftees and anti-war activity in the military should be supported, but those positions were just part of the common currency of the anti-war movement in general and not specific to a revolutionary defeatist strategy as outlined by Macnair. To pin down what distinguishes the theory of revolutionary defeatism in Macnair’s mind from all other anti-imperialist strategies, it is necessary to go deeper into his disagreement with Hal Draper.

Draper’s main criticism of Lenin’s slogan of revolutionary defeatism is that it didn’t distinguish clearly enough between the defeat of one’s own government by another country’s army and the defeat of one’s own government by a revolutionary uprising of its own people. Draper, following Trotsky and virtually all other Bolsheviks save Lenin and Zinoviev, argues that the words “revolutionary defeatism,” “turn the imperialist war into a civil war,” and “the main enemy is at home” are not equivalent in meaning. The first can easily lead to the interpretation that a defeat of one’s own country by an opposing country’s army is to be wished for, whereas the second and third place the class struggle against one’s own government first. In the eyes of Lenin’s critics, this ambiguity disqualified the slogan of revolutionary defeatism as suitable for popular agitation. Draper attributes Lenin’s failure to see this ambiguity to Lenin carrying over the earlier standard Marxist opposition to the reactionary wars of the Russian autocracy into the new era of imperialism where all sides were equally reactionary. As a fact of history, Lenin lost this debate: hardly anyone agreed with his position, and Lenin himself didn’t use the term after 1916. Nevertheless, Macnair thinks Lenin was right and that it is essential for Marxists to continue to use revolutionary defeatism as the name for their anti-imperialist strategy.

The overarching assumption that drives Macnair’s entire argument is that:

The independent class party of the working class, in the broadest sense, is necessarily an international party…. (p. 166)The strategic implication is that against internationally coordinated action of the capitalists, the working class needs to develop its own internationally coordinated action…. (p. 34)

I argue that Lenin’s policy of ‘revolutionary defeatism’ in World War I made sense but has to be grasped accurately and in its context as a proposal for the coordinated action of the workers’ movement on both sides of the war for the immediate struggle for power…. (p. 20)

This judgement of the international situation is, in fact, the hidden secret of the defeatist line for the world inter-imperialist war. In such a war, it is an almost impracticable line for the workers’ party of any single belligerent country. But if the workers’ parties of all the belligerent countries agitate and organize against the war in the ranks of the armed forces, the possibility exists of fraternization between the ranks of the contending armies, leading to the soldiers turning their arms first on the officers and then on their political-economic masters. (p. 75, Emphases in original)

This is the meaning of Lenin’s argument in his polemic against Trotsky that it is essential to his policy ‘that co-ordination and mutual aid are possible between revolutionary movements in all the belligerent countries.’ Such a line assumes that the mass workers’ International exists and that its national sections can be made to follow a common defeatist line. (Emphases in original) (p. 75)

There is no need to go any further down this rabbit hole. The “secret” of Macnair’s theory of revolutionary defeatism is the fantasy that the workers’ movement should and can be organized in a single International in which “its national sections can be made to follow a common defeatist line.” This conception of internationalism didn’t work in WWI, didn’t work with the establishment of the Third International, and didn’t work when Trotsky tried it again with the Fourth. It’s time to admit that such a strategy can’t work because the existence of nation-states makes systematic trans-national coordination impossible, especially under war conditions. Trans-national discussion of the theoretical principles of anti-imperialism, yes; but the primary political location for the practical implementation of those principles must be within the politics of particular nation-states. This is especially true of the US, whose history, power, political system, relative self-sufficiency, and geographic distance from other major countries is unique. Macnair is right that opposition to the Vietnam War within the US is the best recent example we have of a principled mass anti-imperialist movement, but he is wrong that it provides support for his conception of revolutionary defeatism. Macnair claims in one of the quotes cited above that unless Lenin’s conception of revolutionary defeatism is accepted, “you would not go beyond a slogan along the lines of ‘Carry on the class struggle in spite of the war.’ That is, you would not arrive at Lenin’s argument that the principal way to carry on the class struggle in such a war is to argue that civil war is better than this war and to undermine military discipline by anti-war agitation and organization in the armed forces.” Macnair is wrong about this. The internationalist left, best represented by Trotsky and Luxemburg, supported slogans like “the main enemy is at home,” “turn the imperialist war into a civil war,” and “carry out anti-war agitation in the military” independent of any association with Lenin’s defeatist slogan. Whether they also believed as strongly as he did in the necessity of a centralized International with subordinate national sections is beside the point: if that is the real secret of Lenin’s slogan and policy of revolutionary defeatism, all the more reason to leave it dead and buried.

The writing of this article began about a year ago as an effort to figure out how to talk about the Russian invasion of Ukraine; which then led to a comparison of how the New Left reacted to and thought about a similar situation in the 1960s; which then led to a review of Martin Luther King’s thinking about the war in Vietnam and US society and politics in general; and, finally, to Lenin’s slogan and policy of revolutionary defeatism. If there is a common theme running through it, it is that words matter. They have meanings and implications that we have to consider carefully because they are how we indicate which strategic direction for the movement we think is best. These words don’t stand outside the movement; they are partially constitutive of it. In the case of internationalist principles and strategies, many Marxists over the years have taken the ultimate goal of a world without nation-states as their immediate agitational and organizational aim, forgetting Marx’s more specific strategic advice that the struggle of the working class is at first national in form whose primary aim must be the struggle for power. In one of those instances of the cunning of history, it turns out that the New Left and Martin Luther King had a better sense of this international/national political relationship than most Marxists. I think it is a political sensibility that the current left can learn from. DSA and the Marxist Unity Group oppose the US and NATO supplying arms to Ukraine, and that opposition is not based solely on Lenin’s slogan and theory of revolutionary defeatism, but the traditional Marxist over-general internationalist language is still pervasive. I think we need fewer broad-brush declarations of internationalist solidarity and slogans like “revolutionary defeatism” and “No war but class war” and more focus on the strategy and language of establishing a true political democracy in the US.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- “The Practical Policy of Revolutionary Defeatism,” 6/6/2020 ↩

- Matthew Strupp, “The US Proxy War in Ukraine and Socialist Anti-War Strategy,” Cosmonaut, 11/1/2022. Alexander Gallus, “The Russian ‘Threat to Freedom and Democracy,’” Cosmonaut, 2/25/2022, and “Letter on the Reply to ‘The Russian “Threat to Freedom and Democracy,”’” Cosmonaut, 2/27/2022. ↩

- Franz Schurmann, Ideology and Organization in Communist China, (University of California Press: Berkeley, 1970). ↩

- James Miller, Democracy Is in the Streets, (Simon and Schuster: New York, 1987) pp. 96, 122-3, 151-2. ↩

- Martin Luther King, Jr., Why We Can’t Wait (Harper &Row: New York, 1963) p.2. Thanks to Donald Parkinson for pointing out this passage. ↩

- This quote is from Carl Oglesby’s 11/27/1965 speech, “Let Us Shape the Future/Trapped in a System,” sds-1960s.org/documents.htm. I think it complements King’s perspective. ↩

- Martin Luther King, Jr., Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (Harper & Row: New York, 1967) ↩