Introduction

Ruy Mauro Marini is a pillar of Latin American Marxism whose work, after half a century, has yet to have a proper Anglophone reception. Luckily this seems to be changing: Cosmonaut published a translation of his seminal essay “Dialectics of Dependency” in 2021, coinciding with a simultaneous effort by Amanda Latimer and Jaime Osorio (a colleague and collaborator of Marini, as well as a fellow exile from a South American dictatorship) to produce a new translation of the same essay and republish it through Monthly Review. This welcome duplication of efforts suggests that a budding Marini ‘revival’ is building in the zeitgeist, with a recent call for a return to the dependency program in international political economy[1] and the forthcoming release of a special issue on the thought of Marini from the trilingual journal, Reoriente.

The renewed engagement with Marini comes as a welcome, if belated, addition to the wide-ranging debates within critical social theory about how to interpret the past several decades of globalization. Marini’s formidable corpus[2] reflects a continuous engagement with the development of the world capitalist system up until his death in 1997. Because Marini, more than many of his contemporaries, was attempting to think through the structure and process of imperialism, globalization, and the world system with a sophisticated reworking (rather than replacement) of Marx’s theory of capital accumulation, his work has much to teach us now, decades later, about methodology and the viability of a Marxist research program. In the introduction to “Dialectic of Dependency”, Marini identified two theoretical deviations that Marxists commit when trying to analyze Latin American dependency. The first was the substitution of concrete facts with abstractions, unmodified from their lineage in a traditional canon originating in other times and places. The result is a pseudo-orthodoxy that advances readymade but ill-suited analyses and programs. The other deviation seeks to correct the shortcomings of existing theory by liberally intermixing elements from academic social sciences, producing an eclectic hodge-podge of empiricism that is only a “pretended enrichment of Marxism.” No doubt Marxists today will be all too familiar with both of these potential deviations.

Marini is responding to earlier debates about ‘pre-capitalism’ in Latin America. It was common, throughout the first two-thirds of the 20th century, to lament the ‘backwardness’ of Latin America (and the periphery generally). The source of this backwardness was located in the co-existence of capitalist and non-capitalist ‘sectors’ of society. In the structuralism school which came out of the United Nations’ Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), the solution to underdevelopment was to hasten the establishment of proper capitalist social relations, thus placing backward countries in a more competitive position and eventually smoothing out any the anachronistic wrinkles. The so-called ‘endogenist’ Marxists, who dominated the major Communist Parties, rejected this emphasis on hybridity, arguing instead that the problems faced by Latin American countries could be explained purely through the dynamics of uneven development intrinsic to capitalism, demoting any ‘external factors’ to secondary status.[3] Nonetheless, it is clear where Marini’s sympathies lie when he says

even if it is really a question of an insufficient development of capitalist relations, this notion [of pre-capitalism] refers to aspects of a reality which, because of [capitalism’s] overall structure and functioning, will never be able to develop in the same way as the so-called advanced capitalist economies have developed. This is why, rather than a pre-capitalism, what we have is a sui generis capitalism that only makes sense if we contemplate it in the perspective of the system as a whole, both nationally and, mainly, internationally.[4]

However, Marini sought to avoid substituting the particularities of Latin American history with general Marxist premises. The ‘endogenism’/’pre-capitalism’ debates took place before WWII and, therefore, before the accelerated industrialization of the postwar period. In the much-transformed postwar Latin America, the persistence of underdevelopment begged explanation. The orthodox Marxism of the endogenists tended to merely assimilate the Latin American situation to the general developmental problems faced by capitalist countries anywhere. Marini proceeded from the premise that ex-colonial, peripheral countries would “never develop in the same way” due to the global-systematic character of contemporary capitalism. But the late-developing periphery could not be immediately subsumed into the same order of explanation as the advanced capitalist powers, otherwise the “development of underdevelopment” which continued to be observed in the Latin American industrial centers would be inexplicable. Doing so would constitute, as Enrique Dussel puts it, “ a passage to the concrete historical without a sufficient category framework”, in turn getting “lost in a chaotic, unscientific, anecdotal history of dependency.”[5] This inexplicability paved the intellectual path for eclecticism—and, therefore, the kind of bourgeois national-developmentalism against which Marini polemicized. In order to properly conceptualize these new developments, the phenomena could be neither “mixed up” (as structuralist and non-Marxist theorists tended to do) nor “replaced” by prefigured analytic categories (as ‘endogenists’, in their orthodoxy, often did).[6] The categories, instead, had to be logically (re)constructed according to close attention to empirical particularities but without confusing essence and appearance. Just as Marx had constructed categories such as surplus value by developing the contradictions of more abstract categories such as value, the concrete phenomena examined in updated theories could not be shoehorned into the system, in the process destroying either the object or the concepts, but immanently drawn out by a synthetic exposition which respected the levels of abstraction.[7] “Conceptual and methodological rigor: this is what Marxist orthodoxy ultimately boils down to,” Marini concludes, echoing Lukács.[8]

Toward this end, Marini attempts to show, in the present essay, that the emergence of a ‘middle strata’ in the world system is the immanent result of the contemporary phase of global expansion. Through his careful extrapolation from the abstract ‘laws of motion’ of capital, Marini lays out how the relevant phenomena follow from the inherent contradiction between the integration of countries marked by different levels of development into a single, global system. This contradiction amplifies and reproduces underdevelopment. But it also introduces mechanisms by which different levels of development appear in a structured hierarchy, warping the space upon which capitals move and recompose. ‘Core’ and ‘periphery’ are polarizing tendencies in a spectrum, relational terms rather than absolutely distinct categories. Hence, Marini introduces a new term—sub-imperialism—to describe the form taken by a dependent economy when it has reached a stage of development in which domestic capital has become increasingly concentrated and centralized internally, while the situation of dependency remains intact.[9] In this manner, Marini supersedes the previous dichotomy of external heterogeneity or endogenous tendency by explicitly theorizing how exterior and interior are co-constituted within a global system.

In Marini’s telling, the development of sub-imperialism is both historical, i.e. mediated by the contingent action of specific institutions, and logical, i.e. necessitated by the systematic structure of expanded reproduction; a useful term for this might be ‘conjunctural’, which Marini uses but does not define. Historically, the resolution of WWII occasioned the consolidation of money-capital, thus stabilizing capital circulation across international space. The cycle of accumulation that followed initiated a breakneck pace of technical development, accelerating the average turnover time of capital and placing industrial capital at risk of moral depreciation. These conditions facilitated the sale of prematurely cheapened capital goods from the imperial core to the periphery, kickstarting industrialization in these areas. The international division of labor shifted from a system in which the periphery exchanged primary commodities (raw materials, agricultural products, energy) for manufactured commodities from the core to a still-emerging system in which industrial production itself is internationalized. In this new system, a middle stratum gains increasing definition, which exhibits a ‘medium’ organic composition on the global scale and enough of a position to pursue expansionist policies. “The [logical] result has been a rescaling, a pyramidal hierarchization of the capitalist countries and, consequently, the emergence of medium-sized centers of accumulation—which are also medium-sized capitalist powers—that has led us to speak of the emergence of a sub-imperialism.”[8]

Marini is careful to distinguish this middling sub-imperialism from what he called ‘maquiladorization’, the physical offshoring of factories which are like alien enclaves embedded in their local environment, serving the sole purpose of valorizing foreign capital. This distinction is a matter of some controversy today. It is clear that the logic of the maquiladora rules the day, semi-formalized in several thousand Special Economic Zones dotting the globe, constituting the whole of some countries’ manufacturing sector. Most of the recent attempts to debate the theory of imperialism, in light of broader discussions of globalization, tend to focus on whether the concept is still relevant to explain contemporary phenomena and, if so, whether the essence of imperialism has changed, for one reason or another. For many, the noted shift in the international division of labor means that imperialism itself has been made obsolete, resulting in a global capitalism which may be empirically unequal, but only empirically, as a matter of contingency. Theoretically, there is no longer a structure in place that reproduces an imperialist hierarchy.[10] This interpretation is at least partially motivated by the perceived political problems associated with imperialism, which begin with the putative labor aristocracy and only descends downwards toward the aberration of Third Worldism. In short, the theory of imperialism is divisive and undermines internationalism.[11] For others, the persistence and worsening of inequality between nations is a sure sign of continuity in the imperialism structure, even if the much-changed division of labor suggests that the structure has changed shape.[12] In their need to demonstrate the necessity of an updated theory of imperialism, such authors point to the essential maquiladorization of the ‘Global South’ masquerading as development. Wading through the confusion of data about multinational corporate ownership structure, trade in unfinished parts and components, financial flows, and repatriated profits, much of the work carried out in this vein has labored to reconstruct the core’s extraction of value from the periphery. In other words, against the thesis of imperialism’s receding obsolescence, these authors tend to emphasize the enduring binary division of countries into core and periphery.

However, the current debate need not be confined simply to the rejection or renovation of imperialism. What ultimately sets Latin American dependency theory apart from Western Marxism on the issue of underdevelopment is the conceptual distinction between imperialism and dependency. In short, imperialism denotes the stage in which monopoly-finance capital enjoys hegemony and a global field of action but lacks a “specific theory of peripheral and colonial capitalism.”[13] That is, the theory of imperialism is fundamentally concerned with analyzing the conditions that compel capital to internationalize; at a methodological level, the theory is constructed from the perspective of the core, which must, therefore, see the world in such binary terms. This perspective is not necessarily “in a position to understand what kind of world has developed on the dependent periphery of the dominant capitalist system.”[8] This task falls to the explicit theorization of dependency itself, from the vantage of a periphery navigating the contradictory integration imposed by imperialists. The relation of dependency provides the dialectical complement to imperialism, without which the latter appears like an abstract schema to be abstractly confirmed or rejected.

If the export of capital from the imperialist nation marks the moment in which the tendency of capital to internationalize is expressed in pure form, its conversion into productive capital in the framework of a given national economy represents the moment of [this tendency’s] negation, as this capital becomes dependent on the capacity of this economy—and therefore of the state that governs it—to guarantee its reproduction. [Emphasis added][8]

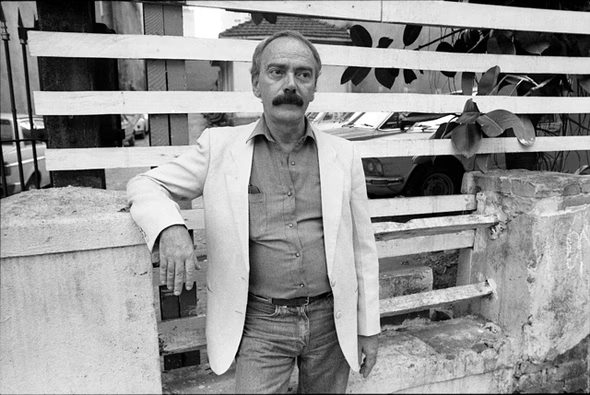

In the very act of exporting capital to the periphery, the core becomes radically dependent upon the periphery developing to a certain level of sufficiency. If an imperialist power that is heavily invested in a given country is capable of totally dominating that country, then this level of development might be more or less precisely calibrated to whatever is necessary for maquiladorization. But this is not necessarily nor uniformly the case. The infusion of ‘medium’ organic composition productive capital, in partnership with the national bourgeoisie, may very well produce the conditions for sub-imperialism. Marini developed the concept of sub-imperialism while considering his home country of Brazil, from which he was exiled in 1964 after the US-backed coup. At first glance, the Brazilian junta seems to be evidence of strict monopolarity, a pure vehicle of US imperialism, as Marini was starkly aware of how the coup fit into the broader strategy of the US. As he argued, the militarization of the Brazilian state reflected a realignment of the Brazilian bourgeoisie away from a popular consensus among fractions toward the domination of a domestic fraction of monopoly capitalists allied with North American imperialist capitals—in other words, the restriction of any space for autonomous maneuver.[14] However, the agglomeration of national and foreign capital within the formally sovereign borders of Brazil places the state in the position of “arbitrat[ing] economic life” on behalf of the dominant capitals, conferring an organizational autonomy and expansionist logic beyond what would have obtained otherwise. The need to “guarantee [imperialist] reproduction” bestows such intermediaries with a “sub-imperialist policy” reflecting a leap in bourgeois self-consciousness slightly beyond their actual economic weight, without, however, making a full break from imperialist hegemony. The dependence of North American capital on the capacity of Brazilian haute bourgeois to construct a developmentalist and counterinsurgent state, able to accumulate capital locally while neutralizing class struggle, placed Brazil on a path toward monopolization and internationalization. The ‘middle stratum’ into which this path leads is not just a transitory quantitative difference in average income, but a difference of political character, neither proper imperialist core nor purely dependent periphery.

Obviously, more work needs to be done to characterize the conjunctural factors which give rise to sub-imperialism and how its painful birth shapes the strategic situation of the proletariat today. But the contemporary world, arguably, offers rich case material for thinking through the complexities of sub-imperialism. Just to take the much-discussed ‘BRIC’ (Brazil-Russia-India-China) as an example, each of these countries exhibits a contradictory mix of advanced technical capacity, dynamic but fraught growth, portfolios with significant market weight, high levels of capital concentration and financialization, and entrenched underdevelopment and mass poverty. As a result, the discussions about their development status tend to be theoretically confused or vague, not least in the Marxist discourse about their respective status vis-a-vis imperialism.[15] But careful attention to the forms of integrated production, the burgeoning outbound investment of their domestic capital, the consolidation of the national bourgeoisie around (especially regional) hegemonic projects, etc., can shed light on the dialectic of dependency at work in these contexts. Without such analysis, actual comprehension of the nature of capitalist globalization will remain elusive. For this reason, a renewed engagement with Ruy Mauro Marini and Latin American dependency theory is timelier than ever.

-Nathan Eisenberg

World Capitalist Accumulation and Sub-imperialism

Source: Cuadernos Políticos n. 12, Ediciones Era, Mexico, April-June 1977.

I

The Second World War corresponded to the culmination of a long period of crisis in the international capitalist economy brought about by the dislocation of forces between the imperialist powers and the emergence of new tendencies in the accumulation of capital. This crisis first manifested itself through the intensification of the struggle for markets, which led to the First World War, and continued in the Great Depression of the 1930s. Its most immediate result was the assertion of the unassailable hegemony of the United States in the capitalist world. Besides allowing the United States to centralize an enormous slice of the international money capital (in 1945, 59% of the world reserves in gold, a figure that would reach 72% in 1948)[16], the war had boosted a feverish economic and technological development in North America, at the same time that it endowed it—thanks to the atomic armament—with an absolute military superiority. The devastation suffered by the capitalist economies of Europe and Japan only accentuated the advantageous position in which the United States found itself.

It fell to the latter, therefore, the task of reorganizing the world capitalist economy, for its benefit. To this end, American imperialism would move in two directions: to re-establish the normal functioning of the international market, so as to ensure the placement of the enormous commercial surpluses that its productive capacity was in a position to generate, and to widen the radius for the accumulation of capital, with the aim of allowing the productive absorption of the immense mass of money that its prosperity engendered. The basic instruments presiding over world capitalist restructuring were the bodies created at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944: the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, or International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), as well as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), signed in 1947.

With the latter, and following the example of England in its hegemonic phase in the last century, the United States sought to impose free trade by removing tariff barriers that might hinder the flow of its exports; GATT is a multilateral agreement between governments, whose main function is the lowering or elimination of tariffs and the achievement of other trade facilities. The IMF and the IBRD were organized according to the rules of private corporations, through capital subscriptions by member countries. In fact, to the extent that they drained the foreign exchange and gold reserves of capitalist countries, they corresponded to international financial trusts. The IMF's function was to finance balance of payments deficits, using the world reserves it had centralized, in order to prevent obstacles to the international circulation of capital from arising; with more than 20% of the votes, when the majority vote usually requires 80%, the United States had the right of veto. The IBRD, using also the world reserves in its possession, had been assigned the task of financing economic development projects, with the purpose of creating conditions for the profitability of private capital; the United States ensured its hegemony [in the IBRD – Eds.] by participating with 30% of the capital.

The role of the US government in the recomposition of the world capitalist economy, for the benefit of US capital, was not limited to multilateral action. It also intervened at the bilateral level, through its foreign aid programs (economic and military), as well as its financial policy. Between 1945 and 1952, total US investments and credits abroad amounted to $190 billion, most of which corresponded to government debts of foreign countries, directly through bilateral operations or through the intervention of international organizations.[17]

However, since the beginning of the 1950s, the bases of US expansion have changed. The inflationary consequences of the Korean War and the massive outflow of private capital abroad (which, after a brief decline, accelerated from 1957 onwards) led to an almost uninterrupted series of deficits in the balance of payments. It should be noted that, although these deficits produced a negative balance of $16 billion between 1950 and 1957[18], the US gold reserve remained practically stable until 1958[19], given the confidence of the European central banks in the stability of the dollar. It was only in the following decade that the currency crisis would occur, leading first to the IMF's special drawing rights, in 1968, through which nations with payment deficits could receive loans in proportion to their own quotas in the institution and pay them back later, and then, in 1971, to the inconvertibility and then to the devaluation of the dollar.

By then, two phenomena of enormous significance had already taken place. Between 1949 and 1968, the dollars-notes in circulation abroad went from 6.4 to 35.7 billion, while the American reserves went down from 24.6 to 10.4 billion.[20] The Eurodollar had been born, on the basis of which the Eurocurrency in general would grow, considerably widening the international monetary circulation. At the same time, the control of this immense monetary mass is progressively transferred to the private banks; the phenomenon is particularly accentuated since the middle of the decade: in 1964, only 11 American banks had subsidiaries abroad, a figure which had risen to 125 in 1974, while their assets increased in the period from a little less than 7 to 155 billion dollars.[21] We will have the opportunity to examine the deep cause of this formidable expansion of the money market.

It was on the basis of the reordering of the world capitalist economy and of the monetary expansion that took place that the American private capital progressively widened the radius of its accumulation, proceeding to integrate under its control the national productive apparatuses included therein. The period of British hegemony had been that of the creation and consolidation of the world market; the period of American hegemony was to be that of the imperialist integration of the systems of production.

At the root of this process is an accelerated process of monopolization. The phenomenon is normal in capitalist economies, but it is amplified as the scale of accumulation increases. Thus we see that, in the United States, in twenty years (1909-1929), the enterprises which had more than a thousand employees and which corresponded, in any of the years considered, to less than 1% of the total number of factories, went from 540 to 921, while the number of workers under their command evolved from one to two million; twenty-five years later (1955), the number of these enterprises was about 2,100, controlling 5.5 million workers. The average size of manufacturing firms, which was 35 workers in 1914, had risen to 40 in 1929 and 55.4 in 1954. This process of concentration is accompanied by an increasing centralization of capital: suffice it to say that the 200 largest corporations in the United States accounted for 35 per cent of the turnover of all corporations in 1935 and 47 per cent in 1958.[22] By 1968, this figure had risen to 66 per cent.[23]

Holding enormous masses of capital, the American monopolies have poured it abroad. American direct investment abroad has increased by 12 to 15 per cent annually; its book value was already $32 billion in 1959, reaching $80 billion in 1970 (a record 22 per cent increase over the previous year). Adding reinvestments abroad and investments in securities, U.S. assets abroad totaled $120 billion at the latter date, generating sales of $250 billion, or five times as much as merchandise exports from the United States.[24]

It is thus understandable that multinational production in all countries corresponded, in 1968, to a quarter of the world gross national product at market prices and that some estimates predict that this figure will be 53 per cent in 1998.[8] The weight of North American capital is undeniable, corresponding to 61% of the world total of direct investment, in the year considered.[25]

II

Capital exports are not in themselves a new feature of the contemporary period of capitalism. We find them since the middle of the last century, mainly in the form of British portfolio investments, and later, driven mainly by the United States, in the form of direct investments, almost always in agricultural and extractive activities. What is new today is the scale that capital investments outside their country of origin have reached; the predominance of direct investment and, more recently, the weight of loans and financing; the breadth of the geographical radius they cover; and the increasing percentage devoted to manufacturing industry (see Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1: U.S. Investments Abroad (in billions of dollars)

Total

Western Europe

Canada

Latin America

Type of investment

1955

1965

1968*

1968*

1968*

1968*

Private investment

29 136

81 197

101 900

28 124

31 679

17 077

Long term

26 750

71 044

88 930

24 687

30 476

13 791

Direct

19 395

49 474

64 756

19 386

10 488

11 010

Other

7 355

21 570

24 174

5 301

10 98

2 781

Short Term Assets

2 386

10 153

12 970

3 437

1 203

3 286

US Government loans

13 142

23 479

28 524

011

011

5 204

TOTAL

65 076

120 176

146 134

39 658

31 694

22 281

Source: U. S. Department of Commerce, cited by Tarmanter, op. cit, p. 339 * Provisional dataTable 2: Value of United States direct investment abroad, by branch of activity (in billions of dollars)

Activities

1950

1960

1970

Total

11 788

32 765

70 763

Manufacturing

3 831

11 152

29 450

Petroleum

3 390

10 948

19 985

Public Services

1 425

2 548

2 676

Mining and Metallurgy

1 129

3 001

5 635

Commerce

762

2 397

5 832

Others

1 251

2 709

7 194

Taken from Chapoy, op. cit., p. 109.This necessarily had to modify the structure of the companies that respond to this characteristic feature of contemporary capitalism. Under the generic denomination of multinationals (some authors consider it more appropriate to call them transnationals)—understanding as such those companies that have 25% or more of their investment, production, employment or sales abroad[26] — these companies have subsidiaries located in different parts of the world and cover the most diverse fields of activities, being able to operate simultaneously in agriculture or the extractive industry, in the manufacturing industry, commerce and services. The national origin of the capital is lost in an intricate process of associations, mergers and agreements, in such a way that a company located in country A can make a joint investment with another one in country B and this can be transferred to country C, which in turn makes it rebound on country A. We find among them true economic giants, whose total production in many cases exceeds the national product of most countries (see Table 3).

Table 3: The 100 largest “GDPs” in 1969, excluding socialist countries and international commercial banks (in US $ billion)

1.

United States

931.4

34.

IBM

7.2

67.

Goodyear Tyre & Rubber

3.2

2.

Japan

164.8

35.

Chrysler

7.0

68.

RCA

3.2

3.

West Germany

153.7

36.

South Korea

7.0

69.

Algeria**

3.2

4.

France

137.8

37.

Mobil Oil

6.6

70.

Morocco

3.2

5.

United Kingdom

108.6

38.

Thailand

6.3

71.

SWIFT

3.1

6.

Italy

82.3

39.

Colombia

6.1

72.

South Vietnam**

3.1

7.

Canada

73.4

40.

Indonesia

6.0

73.

McDonnel Douglas

3.0

8.

India

39.6

41.

Unilever

6.0

74.

Union Carbide

3.0

9.

Brazil

39.4

42.

Texaco

5.9

75.

Bethlehem Steel

2.9

10.

Australia

29.9

43.

Egypt*

5.7

76.

British Steel

2.9

11.

Mexico

29.4

44.

Chile

5.5

77.

Hitachi

2.8

12.

Spain

28.7

45.

ITT & Grinnel

5.5

78.

Boeing

2.8

13.

Sweden

28.4

46.

Portugal

5.4

79.

Libya***

2.8

14.

Netherlands

28.4

47.

New Zealand

5.3

80.

Eastman Kodak

2.7

15.

General Motors

24.3

48.

Peru

5.1

81.

Procter & Gamble

2.7

16.

Belgium-Lux.

22.9

49.

Gulf Oil

4.9

82.

Atlantic Richfield

2.7

17.

Argentina

19.9

50.

Western Electric

4.9

83.

North Amer. Rockwell

2.7

18.

Switzerland

18.8

51.

US Steel

4.7

84.

Intern. Harvester

2.6

19.

South Africa

15.8

52.

Israel

4.7

85.

Kraftco

2.6

20.

Standard Oil NJ

15.0

53.

Taiwan

4.6

86.

General Dynamics

2.5

21.

Ford Motor

14.8

54.

Standard Oil Cal.

3.8

87.

Montecatini Edison

2.5

22.

Pakistan

14.5

55.

Malaysia

3.7

88.

Tenneco

2.4

23.

Denmark

14.0

56.

Ling-temco-vought

3.7

89.

Siemens

2.4

24.

Turkey

12.8

57.

Du Pont

3.6

90.

Continental Oil

2.4

25.

Austria

12.5

58.

Phillips

3.6

91.

United Aircraft

2.3

26.

Royal Dutch/Shell

9.7

59.

Shell Oil

3.5

92.

British Leyland

2.3

27.

Norway

9.7

60.

Volkswagenwerk

3.5

93

Kuwait

2.3

28.

Venezuela

9.7

61.

Westinghouse

3.5

94.

Daimler-Benz

2.3

29.

Finland

9.1

62.

Standard Oil. Ind.

3.5

95.

Fiat

2.3

30.

Iran

9.0

63.

B. P.

3.4

96.

Firestone

2.3

31.

Greece

8.5

64.

Ireland

3.4

97.

August Thyssen-Hutte

2.3

32.

General Electric

8.4

65.

Gen. Tel. & Electronic

3.3

98.

Toyota

2.3

33.

Philippines

8.1

66.

ICI

3.2

99.

Farbwerk Hoechst

2.3

100.

Basf

2.2

* 1967, ** 1968, *** est. 1969Source: Data from Vision (Paris), cited by Levinson, op. Cit. p. 109.

Among the reasons that determine multinational investment, we can of course identify the profitability factor, i.e. its effect on the profit share of the company. It is known, for example, that the rate of profit of American investments abroad is approximately double that of domestic investments.[27] Among the many elements that work to make it so, such as transport infrastructure, energy, etc., the existence of raw materials and others, and despite the contrary opinion of some authors,[28] the cost of labor has an influence. It is significant, in this sense, to take into account the wage differences between the United States, on the one hand, and Japan and Western Europe (in the case of the latter, the wage rate has been influenced to a large extent by the importation of foreign workers), as well as Latin America and other underdeveloped areas, where American investments have been directed (see Table 4). Equally significant is the market factor, since the subsidiaries of multinational companies have in view, in the first place, the available domestic market, as well as nearby markets; we will return to this point later.

Table 4: Salaries in the manufacturing index for several countries in 1967 (US $/hour)

Country

Average Salary

South Korea

0.13

Taiwan

0.23

Singapore

0.31

Hong Kong

0.33

Brazil

0.45

Japan

0.67

United Kingdom

1.16

Australia

1.20

Federal Republic of Germany

1.28

Sweden

1.80

United States

2.83

Taken from Córdoba Chávez, J. A., La política brasileña de exportación de manufacturas, Institut of Social Studies, Den Haag (Nl.), 1975With it, the world capitalist market reaches its full maturity. As Granou says:

In order to see a true internationalisation of capital develop, it will be necessary to wait for the modification of the conditions of production, which will mark the end of the stage of big industry. These new conditions of production were to develop through a direct exploitation of inequalities, that is to say, through the rate of profit and consequently of the social conditions of production between different countries, extending the process of production to different countries. From then on, if a given capital is divided between different countries, its valorisation is nevertheless carried out directly on a world scale, thus constituting a world market—of capitals and therefore of commodities—in which the profitability of the different accumulated capitals must be confronted. This internationalization of the market thus allows the realization of the value of commodities directly on a world scale, i.e. independently of their country of origin and destination.[29]

A second reason for the expansion of capital exports relates to the sharp increase in capital goods or related industries such as war material that has taken place in the United States during the world conflict and in the immediate years, and which has also been observed subsequently in Western Europe and Japan. The growth of production in branches such as electronics, heavy chemicals, machine tools and others has determined the need to invest in manufacturing industry in other areas in order to create markets for it, as well as first in the already developed countries of Europe and Japan and then, although on a smaller scale, in the underdeveloped areas - transferring part of the production itself there. This explains Mandel's observation that the production of traditional industrial goods, such as those of the textile and iron and steel industries for example, grows at a much faster rate than the respective world sales; this phenomenon does not occur, or occurs in a much more attenuated form, with respect to "new" products, such as those mentioned above.[30]

It is evident that, in new industries, the amount of investment required by constant capital, particularly fixed capital, points to a high organic composition, which constantly threatens the profit share. It is understandable, then, that large firms seek to diversify their activities into fields of investment with lower organic composition, such as agriculture or services.[31] One of the most characteristic and least studied phenomena of contemporary capitalist accumulation is precisely the fact that capital increasingly seeks to shift the profit levelling mechanism from the area of inter-firm relations, as it normally occurred in the phase of competitive capitalism and still to a large extent in pre-war capitalism, to the area of intra-firm relations, that is, between its different subsidiaries.

This is accentuated by the reduction of the amortization period of fixed capital, as a consequence of the technological innovations caused by the world war and the subsequent arms race, which, according to Mandel, would have been reduced by half, falling from eight to four years. Driven by the spring of extraordinary surplus value, the monopolies are forced to replace fixed capital before it is fully depreciated. Their export to less technologically developed areas, where they still represent innovations and where a lower paid labour force is available, allows depreciation to be completed and keeps the way open for technological renewal in the advanced capitalist centres.

It is also necessary to consider that technological progress does not only affect the circulation of productive capital, but also, and in a decisive way, the circulation of money capital. By shortening the rotation of the cycle of circulating capital, technological innovations, and the consequent increase of productivity, lead to the fact that a certain part of the disbursed capital becomes superfluous for the production process and is detached from it, unless and until the scale of production is enlarged. Thus expelled from the orbit of productive capital, this capital will nevertheless pursue its valorisation and seek a return to the productive sphere, through the financial market. This is what explains the expansion of the money market, which manifested itself in the aforementioned banking boom and responded to a large extent to capital export flows. Contrary to what is generally supposed, these do not derive exclusively from the surplus value generated, but also from the very mechanics of the reproduction of capital, that is to say, from the disengagement of the disbursed money capital due to the simple effect of the reduction of the period of rotation.

Let us note that this introduces a clear element of periodization in the financial development of the last decades. It is necessary to distinguish there the increase of the financial circulation promoted by the American state, in the immediate post-war period, backed by its considerable reserves in foreign currency, and that even adopted to a certain degree the form of donations, and the one registered in the last decade, whose propelling engine were the private banks and the same productive capital constituted or developed in the previous period. As we shall see, this will have an impact on international relations, leading to the decline of the monopolarity in the capitalist world characteristic of an epoch in which the accumulation of capital on a world scale was under the aegis and impulse of a State, and to the emergence of a hierarchical integration of the centers of accumulation, characteristic of the period in which private capital fully recovers the reins of its own valorization process.[32]

In any case, the expansion and acceleration of both the circulation of productive capital and the circulation of money capital have been configuring a new capitalist world economy, which rests on a scheme of international division of labor different from the one that ruled before the world crisis we mentioned initially. The time of the simple center-periphery model, characterized by the exchange of manufactures for food and raw materials, has passed. We are facing an economic reality in which industry assumes an increasingly decisive role. This is true even as industrial capital expands and strengthens in extractive and agricultural areas; even more so when we consider the global spread and diversification of manufacturing industry. The result has been a rescaling, a pyramidal hierarchization of the capitalist countries and, consequently, the emergence of medium-sized centers of accumulation—which are also medium-sized capitalist powers—which has led us to speak of the emergence of a sub-imperialism.[33] This process of diversification, which is simultaneously a process of integration, continues to have at its head the superpower that the world crisis brought about: the United States of America.

III

Latin America entered this new stage of capitalist development in relatively favorable conditions compared to Africa and most of Asia. In the period of the world crisis between the wars, the relatively more developed Latin American economies, such as Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Chile and Uruguay, managed to promote a process of industrialization, which would later spread to Venezuela, Central America, and other countries. This allowed Latin America to take advantage of the changes taking place in the international capitalist economy to strengthen its manufacturing industry.

This is illustrated by the behavior of U.S. investment in the area. After the reduction it experienced as a result of the 1929 crisis, which meant that its value fell from 3.5 billion dollars at that time to 2.7 billion in 1940, US direct investment began to recover, and in 1950 it slightly exceeded the 1929 figure. But, now, with a different sign: while, in 1929, U.S. direct investment in Latin American manufacturing industry represented only 6.7% of the total, in 1950 it reached 19.1%; this percentage will increase, growing faster than total investment, to represent 32.3% of the total in 1967 (see Table 5). Three countries account for more than two thirds of [foreign investment into Latin America – Eds.] and, in these countries, the share of the manufacturing sector is much higher than the average: 64% for Argentina, 68% for Mexico and 69% for Brazil, in 1968, according to ECLAC data.[34]

Table 5: U. S. direct investments in Latin America* (in billions of dollars)

Year

Direct FI

FI in manufacturing sector

% of Direct FI in manufacturing

1929

3.5

0.2

6.7

1940

2.7

–

–

1950

3.8

0.7

19.1

1960

7.4

1.5

20.2

1965

9.4

2.7

29.2

1967**

10.2

3.3

32.3

* Excluding Cuba and countries which are not members of OEA** Preliminary

Source: U. S. Department of Commerce, Survey of Current Business, 1967

Let us note in passing that the above-mentioned periodization of the predominance of public and private capital in financial circulation is also valid for the region, although with some years of delay. In effect, the flow of public and private capital from the United States to Latin America - without considering military aid or the inverse flow of amortization, interest, remittance of profits, payment of royalties, etc. (which yields a negative balance) - was $2.8 billion in the 1960s. US government capital participated there with 51%. However, if we distinguish two sub-periods, 1961-65 and 1966-70, we observe that the participation of private capital rose from 45% in the first to 68% in the second.[35]

This penetration of foreign capital into the Latin American economy, and particularly into its manufacturing sector, is presented by some authors as a process of internationalization of the domestic market. The expression lends itself to confusion. Although it is true that, between the 1920s and 1940s, Latin American industry achieved, in some countries, an important weight in the domestic market—what is known as the first phase of import substitution industrialization—, the very fact that this was a process of substitution indicates that it corresponded to an increase in the share of national production in an already constituted market, and constituted precisely with an internationalized character. What really characterizes the post-war period is the reconquest of that market by foreign capital, no longer through trade, but rather through production. More than the internationalization of the domestic market, it is a question of the internationalization (and the consequent denationalization) of the national productive system, that is to say, of its integration into the world capitalist economy.

This productive integration takes place in a different form than the one that began to operate at the end of the last century, through the so-called "enclaves", which consisted of the simple annexation of production areas (generally extractive, but also agricultural) to the industrialized centers, leaving these areas outside the national productive structure, except for the transfer of value through taxation and, to a lesser extent, through wages. Now it is a question of linking foreign capital to a sector of the national productive structure, which has as a counterpart its denationalization in terms of ownership, although not its subtraction from the national economy. It should be noted that not all foreign investment in industry has this character, since it can consist, as in the case of the enclave, in a process of economic annexation; we will return to this point later.

While the development of the productive apparatus brought about by foreign investment is undeniable, it is necessary to take a closer look at its effect on the Latin American economy. A first aspect to consider is the accentuation of the process of concentration and centralization of capital derived from it. As we pointed out, this accompanies the expansion of the scale of capitalist accumulation, being a natural phenomenon; however, due to the economic conditions of the advanced countries, in which the technological levels and the minimum capital required for the start-up of production are higher, foreign investment, when it affects a more backward economy, suddenly provokes a strong concentration of capital and leads promptly to centralization. In Brazil, a sample of the largest industrial companies showed that 44.4% of the foreign companies that operate there employ more than 500 people, a percentage that, when referring to national companies, drops to 13.5%. On the other hand, of the 1,325 foreign affiliates in Latin America, only 48.2% are new companies; 35.8% are acquired companies and part of the remaining 8% result from mergers, both cases being an expression of the centralization of capital.[36]

A usual form, and one that is gaining increasing prestige among multinationals, is the association with local companies. Levinson points out in this respect that, two decades ago, almost 75% of the North American subsidiaries abroad were wholly owned, but that, at present, the proportion is only 40% and tends to decrease.[37] There are also many cases in which the ownership of the company is national, but it is linked to multinational groups by financial and technological ties. All this has led to the crystallization in Latin America of a stratum of big business, that is, big capital, whose superiority over the rest of the capitalist class is overwhelming. Chile, which was not, however, among the countries in which foreign capital had penetrated more at the level of manufacturing industry, showed in 1968 the spectacle of a set of large companies that, representing 3% of the sector, controlled 44% of employment, 58% of capital and 52% of the surplus value generated in the industry. Other data indicate, for the same date, that less than 4% of large industrial companies participated with 49% of total sales generated by the manufacturing sector.[38]

If taken in these terms, Latin American industrialization has had an unfavorable impact on job creation. There has been a twofold process: on the one hand, the forms of land tenure and the introduction of technological innovations in agriculture, as well as the expectations of employment and wages brought about by the manufacturing industry, have generated strong movements of internal migration and an accelerated process of urbanization. On the other hand, largely due to the increase in the level of technology, but also due to limitations in the rate of investment, the working mass has faced increasing difficulties in finding work. Venezuela, which entered a phase of feverish industrialization in the post-war period, illustrates the phenomenon well: between 1950-59, the labor force grew by 684,000 people seeking employment, which gives an average supply of 67,000 people per year. However, the percentage of unemployment with respect to the labor force practically doubled in the decade under consideration, going from 6.2% in 1959 to 13.7% in 1960.[39] With greater or lesser intensity, the phenomenon is repeated throughout Latin America and is aggravated by underemployment, or disguised unemployment, which has been estimated by the International Labor Organization, for urban areas, at about 30 to 40% of the labor force. Estimates for the countryside are even less precise and reliable, but the very migrations to urban centers would suffice to indicate the magnitude of the latent overpopulation found there.

The pressure of this immense industrial reserve army is undoubtedly one of the factors that put pressure on the level of wages in the region. It is significant to note that the share of wages and salaries of workers in the aggregate value of the manufacturing sector in Brazil is half of what it is in the United States and England (see Table 6). On the other hand, the number of workers, in all sectors, who earn up to the minimum wage in Brazil has been increasing in recent years (see Table 7). The positive aspect that the phenomenon may hide - the increase in remuneration in the artisan and small industry sectors to the level of the minimum wage and the destruction of mixed forms of payment in the countryside - is neutralized when we consider the decrease in the minimum wage, in real terms (see Table 8).

Table 6: Wages and salaries of workers as a percentage of value added by manufacturing

Country

Year

%

Chile

1963

15

Peru

1963

18

Brazil

1963

18

Iran

1963-64

19

Colombia

1963

21

Mexico

1963

21

Japan

1963

24

United States

1963

32

United Kingdom

1963

37

Source: United Nations, taken from Little, J. et al., Industria y Comercio en algunos países en desarrollo. Fondo de Cultura Económica, México, 1975, p. 66.Table 7: Brazil: Percentage of workers that earn minimum wage

Year

Up to minimum wage

Over minimum wage

1965

24.3

75.7

1970

40.4

59.6

1972

57.6

42.4

Source: Annual Statistics, IBGE.Table 8: Brazil: Real minimum salary index (1965: 100)

Year

Index

1961

111.0

1965

100.0

1970

80.3

1972

81.6

1974

78.1

Source: Annual Statistics, IBGE.Finally, we must consider the impact of foreign capital on the industrial structure. We have already pointed out that, in the United States and later in the other advanced countries, new branches of production have developed, which are largely due to the development of capital exports. Although many of the products derived therefrom, directly or indirectly, are frankly sumptuary in Latin American conditions,[40] it has been in function of them that, for the convenience of foreign capital, the productive structure has been altered. The case of Brazil is significant. In 1950, the textile and food branches accounted for 50% of the total value of production; in 1960, this proportion dropped to 36.24%, while the participation of the transport material branch rose from 2.28% to 6.7%, of the chemical industry from 5.13% to 8.85% and of metallurgy from 7.51% to 10.4%; in 1970, the textile and food branches contributed only 29.49% of the total, while the other three rose to 8.2%, 10.89% and 12.47%, respectively.[41] Although this appears, in the abstract, as natural and good, we must bear in mind, to take just one example, that the transport material branch is strongly influenced by the automobile industry, which mainly produces cars and which has been the axis of Brazilian economic expansion in recent years, ranking ninth in world production and directly inducing the development of metallurgical and chemical production, etc. The data for Chile indicate, in turn, that between 1960 and 1967, while the transport material branch grew at an annual average of 16.7%, the clothing and footwear branch had an annual average growth rate of only 1.4%, lower than the population growth rate.[42]

It is natural that, under these circumstances, Latin American industrial development tended to rely on the expansion of the market constituted by high and middle-income groups, thus divorcing itself from the consumption needs of the masses. The extreme concentration of income in the region is the necessary counterpart of the stratification that has been taking place at the level of the productive apparatus. This also made indispensable the direct intervention of the State, which not only acts as a creator of demand, but also removes obstacles to the realization of production and even artificially encourages it, absorbing part of the costs of production.[43] However, Latin American industry is incapable of satisfying itself with the domestic market and has structural limitations to proceed to expand it in an accelerated manner. It is therefore necessary to open up to the outside world, which has turned the export of manufactured goods into the most heartfelt slogan of large foreign and national capital in Latin America.

IV

This is a recent phenomenon, which only gained importance in the second half of the last decade. Indeed, some studies indicate that, by 1965, foreign companies located in Latin America were allocating 93% of their production to local sales, leaving only 7% for export; the proportion had remained roughly the same since 1957.[44] This is consistent with the situation of the country where the change in trend has been most pronounced: Brazil. In 1964, Brazil’s manufactured exports amounted to less than $100 million and represented only 7% of its total exports.[45]

Since then, things have changed substantially for Brazil. In 1972, its manufactured exports already reached $1 billion, equivalent to a quarter of its total exports (see Table 9); there are cases such as Mozambique, to which Brazilian manufactured exports increased more than tenfold in three years, from $92,000 to $968,000 between 1968 and 1970. The role played there by the subsidiaries of multinational groups has been relevant. In 1967, one out of four foreign companies in Brazil exported manufactured goods; the ratio increased from one to three in 1969. In the latter year, exports of manufactured goods from foreign companies reached 43% of total exports in the sector; in the machinery and vehicles branches, this share was 75%.[46] With less intensity, the phenomenon is also present in other countries of similar relative development, such as Mexico and Argentina, but also in less developed countries, such as El Salvador.

Table 9: Brazil: Total and manufactured exports

Year

Total value of exports (in $ billions)

Indexed at 1968

Value of manufacturing exports (in $ billions)

Indexed at 1968

% of value from manufactured exports

1967

1 654

87.9

294

106.5

17.8

1968

1 881

100.0

276

100.0

14.7

1969

2 311

122.9

366

132.6

15.8

1970

2 739

145.6

531

192.4

19.4

1971

2 904

154.4

678

245.7

23.3

1972

3 987

212.2

1 032

373.9

25.9

Source: FGV data: Cuentas Nacionales and CIEF-IPEA: Comercio Exterior do Brasil, taken from Von Doellinger, op. cit.There is often a tendency to confuse the export of manufactures with the concept of sub-imperialism. Of course, the latter implies the export of manufactures, just as the struggle for markets is also present in the concept of imperialism. However, the very way in which the export of manufactures is carried out, that is, the form that the phenomenon assumes, already points to differences, which point to the fact that it is not enough to export manufactures to be a sub-imperialist country. It is significant to note that one of the forms of export of manufactures that is registered in Mexico and that predominates in the Philippines, South Korea, Hong Kong—that of the maquiladoras, through which plants located in national territory finish or assemble parts and components received from foreign plants and return them to these for the final process—is far from generating sub-imperialist tendencies, to the extent that the country where the maquila industry operates does not need to struggle for the conquest of markets. The essential characteristic of the maquila is that it is a phase of the production process referring to the cycle of reproduction of an individual capital, which is carried out in a national sphere foreign to the one in which this cycle takes place. This implies that—as it happened in the old enclave economy—a certain factor of production (in this case, the labor force) is subtracted from the dependent economy and incorporated to the capitalist accumulation of the imperialist economy, thus configuring a case of economic annexation. The reason why this situation must be differentiated from the one that gives rise to sub-imperialism will be better understood when we analyze the incidence of the national in the process of internationalization of capital.

Some authors also question the significance of manufacturing exports from the point of view of the realization needs of production. This questioning is usually done both by arguing that there are no problems of realization for capitalist production in general, and Brazilian production in particular[47] and—for those who do not deny the difficulties generated for the expansion of the domestic market in Brazil by the super-exploitation of labor and the regressive distribution of income—by emphasizing the demand generated by the middle strata and the state.

With respect to the first objection, we have already pointed out, on another occasion, that those who maintain the impossibility of problems of realization in the capitalist system are merely grossly confusing Marx with Say. When Marx demonstrates, in Book II of Capital, how production resolves itself into realization, he places himself at the highest level of abstraction and simply tries to determine the laws governing the reproduction and circulation of capital as a whole. He does not pretend in the least to derive from it—this he leaves to the bourgeois apologists—the non-existence of problems of realization in the system and, on the contrary, he gives several indications about them, throughout his work. It is Lenin who cuts off the discussion more sharply. [In “On the Problem of Markets”, Lenin writes]

The question of realization is an abstract problem, linked to the theory of capitalism in general. Whether we take a single country or the whole world, the fundamental laws of realization discovered by Marx are always the same. The problem of foreign trade or of the foreign market is a historical problem, a problem of the concrete conditions of the development of capitalism in this or that country, in this or that epoch. [All the other laws of capitalism discovered by Marx represent [...] only an ideal of capitalism, but never its reality. [Lenin continues:] From this theory [of realization – RMM] it follows that, even if the reproduction and circulation of capital as a whole were uniform and proportional, the contradiction between the increase of production and the restricted limits of consumption cannot be avoided. [And he concludes:] Moreover, the process of realization does not unfold in reality according to an ideally uniform proportion, but only through difficulties, 'fluctuations', 'crises', and so on.[48]

Trying to contrast the outflow with the demand created by the middle strata or the state—directly, as a buyer, and indirectly, through its productive and unproductive expenditures—is also futile. In previous works[49], we had not only underlined the importance of these two types of demand in the scheme of sub-imperialist realization, but we also pointed out their limits. But, although they do not advance much with respect to what was already known, there are theses derived from that contraposition that can be harmful, taking water to the mill of those who, from one or another position, ideologize the Brazilian capitalist system. This is what happens with the so-called "third demand," to which Salama resorts[50], following in the footsteps of some Brazilian authors.

It is true that Salama affirms that this 'third demand' derives from a redistribution of income 'to the detriment of the working class' (preferring to situate himself at the level of distribution and not of income formation, thus avoiding the question of the super-exploitation of labor). However, the very expression "third demand" confuses, insofar as it obscures the fact that individual consumption, in a capitalist economy, can only be generated from two sources: wages and surplus value, wages being understood here as the remuneration par excellence of the working class. Moreover, he gives the basis for denying (or rather, the expression seems to have been forged for this purpose) the split in the sphere of commodity circulation between working-class consumption and that which arises from unaccumulated surplus value.[51] Thus, after indicating that his 'third demand' includes the middle groups and sectors of the working class (the 'most skilled workers'), Salama states that 'the recomposition of industrial employment thus makes it possible to attenuate the incommunication that exists between the two spheres of consumption', to conclude that 'it is false to want to achieve an absolute incommunication between the two markets...' (Salama's emphasis – RMM).

Let us leave aside the two markets, which end up being three, and the lack of communication between them, which exists and does not exist, to point out that, at a certain level of abstraction, it is necessary to determine precisely the factors that give rise to economic phenomena; this is what authorizes Marxist authors to speak of "wage goods", even if it is evident that, worker or bourgeois, everyone consumes them. If the sumptuary demand is sustained fundamentally by the capitalist class and by the middle and upper petty bourgeoisie, it is to them that such demand must be attributed, and not to that contingent of worker—larger or smaller, according to the phase of the cycle—which can have access to it.[52]

Let us take an example from Brazil. Official data for the personnel of ten branches of industry in São Paulo indicate that, in 1969, 94.29% was made up of unskilled workers, who received less than two minimum wages (we have already pointed out the deterioration suffered by the minimum wage), and that those at a higher level (which included, moreover, even managers) did not reach 1% of the total, receiving almost 15 times the minimum wage (see Table 10). It is this small percentage (about 7,500 people out of more than a million) that can be assimilated to the demand corresponding to the upper sphere of circulation, on a permanent basis; the proportion of the middle stratum capable of partially accessing it varies according to the phase of the cycle, as we have already indicated; however, taking into account that the average level of consumption is low and the fact that, on average, the remunerations of this stratum are only two. However, considering that the average level of consumption is low and the fact that, on average, the remuneration of this stratum is only 2.6 times higher than the total average remuneration, it is safe to assume that in the specific conditions of Brazil, this proportion, even in a phase of prosperity, such as 1969, tends to be very small.

Table 10: Sao Paulo: Distribution of personnel employed in ten industrial branches by degree of specialization and wage level, 1969

Degree of Specialization

Employee number

%

Average remuneration (cruzeiros)

Ratio between remuneration and minimum wage

None

944 886

94.29

302.82

1.9

Medium level

49 804

4.97

901.20

5.8

High level

7 416

0.74

2 298.56

14.7

Total

1 002 106

100.00

347.21

2.2

- The branches are: food products, textile, garment and footwear, paper and cardboard, chemistry and farmaceutics, plastic articles, non-metallic minerals, metallurgy, mechanics and electrical and electronic material, and construction and repair of vehicles.

- The grouping by strata is made from the tasks performed by the personeel at the firm.

- The minimum salary in Sao Pauolo, in 1969, was of 156.00 cruzerios.

There would be other aspects to consider in Salama's approaches, which are not relevant here.[53] But it is preferable to take the significant case of a branch that produces consumer goods— clothing and footwear— in order to validate the argument that denies Brazilian capitalism the need to resort to the foreign market to expand and realize its production. A typical branch [of the ‘traditional economy’ – Eds.], with vegetative growth, even considering a year of crisis, 1965, as the base year, the production index does not go beyond 112.9 in 1970, with the case of 1969—already in full prosperity—in which it fell to 95.7.[54] Taking advantage of the incentives to export (see Table 11), the manufacturers launched themselves into the foreign market (mainly the North American market). From 2.6 million dollars, which they were already exporting in 1969, they went to 11.3 in 1970, to 43.2 in 1971 and to 88.9 million dollars in 1972, jumping from the discreet 18th place they occupied in the pattern of manufacturing exports in 1967 to 5th place in the last year considered. Let us note in passing that, out of the ten industrial branches of São Paulo mentioned above, in 1969, it is the clothing and footwear branch that presented the lowest salaries, occupying the last place on the scale, with an average salary equal to 1.5 times the minimum salary and, therefore, lower than the total average (2.2 times the minimum salary).[55] Recently, in the face of the protectionist measures taken by the Brazilian government, it was the clothing and footwear branch that presented the lowest salaries. Recently, in the face of the protectionist measures adopted by the United States, footwear exporters have pressured the Brazilian government to grant them greater export facilities, affirming: "The internal market would not be able to absorb more than 30 or 40% of all national production destined for the external market."[56]

Table 11: Brazil: Theoretical effect of incentives for manufacturing exports, 1972

Sale price in internal market, without sales tax

100.00

Direct deductions

Total exemption from sales tax

16.00

Fiscal credits: sales and consumption tax

13.40

Credits on the sales tax

1.00

Total

30.40

Indirect deductions

Savings in marketing

17.00

Exemption from income tax

3.00

Reduction of financing costs

2.00

Use of surplus capacity

2.00

Exemption from import tax

1.00

Exemption from other taxes

0.20

Total

25.20

Total deductions

56.60

Other costs

Packing and port rights

2.80

Final price

46.20

Total reduction from sales price

53.80

Calculation by Pinto Bueno Neto, F. P., “Exports of Manufactured Goods: Effects of Incentives of Formations of Selling Prices”, in Brazilian Business, January, 1973. Taken from Córdova Chávez, op. cit..V

We have defined sub-imperialism as the form assumed by the dependent economy when it reaches the stage of monopolies and financial capital. Sub-imperialism implies two basic components: on the one hand, a medium organic composition on the world scale of the national productive apparatuses and, on the other hand, the exercise of a relatively autonomous expansionist policy, which is not only accompanied by a greater integration to the imperialist productive system but is maintained within the framework of the hegemony exercised by imperialism on an international scale. Put in these terms, it seems to us that, independently of the efforts of Argentina and other countries to accede to a sub-imperialist rank, only Brazil fully expresses, in Latin America, a phenomenon of this nature.

In the absence of more precise data, the organic composition of a nation's capital can be inferred from the share of its manufacturing product in the gross domestic product. UNCTAD calculations for the middle of the last decade, referring to 92 underdeveloped countries, show that (naturally excluding Yugoslavia,the only socialist country considered, as well as the Philippines, given the predominance there of the maquila industry) only six countries presented, in this aspect, a participation index equal to or higher than 25%. Among them, the three Latin American countries with the highest relative development, with respect to which—from the strictly economic point of view—sub-imperialist features have been registered: Brazil, Argentina and Mexico. Iran, together with Brazil, is a typical case of sub-imperialism; something similar could be said of Israel. Spain, due to historical factors and its very geographical location, enjoys a very particular situation, to be compared with the others (see Table 12).

Table 12: Manufacturing sector participation in the gross internal product for several countries

Country

Year

%

Argentina

1965

34

Mexico

1965

29

Brazil

1964

27

Iran

1963

29

Israel

1965

25

Spain

1964

26

Source: UNCTAD, taken from Tamames, op. Cit., pp. 68 and ss.Brazilian sub-imperialism is not only the expression of an economic phenomenon. It results to a large extent from the very process of the class struggle in the country and from the political project defined by the technocratic-military crew that took power in 1964, together with conjunctural conditions in the world economy and politics. The political conditions are related to imperialism's response to the transition from monopolarity to hierarchical integration, which we have already mentioned, and more specifically its reaction to the Cuban revolution and the rise of the masses in Latin America in the last decade; we will not dwell on these issues here. The economic conditions are related to the expansion of world capitalism in the 1960s and its particular expression: the financial boom.

We point out that the boom begins in the middle of the last decade, but at the beginning this affected little the underdeveloped countries. It is from 1970 that the flow of private capital, in particular of Eurocurrencies, moved towards them. Brazil became one of the first recipients, at the very moment when the Eurocurrency market doubled, in less than four years, its availabilities: from $45 billion in 1969 to $82 billion in half of 1972.[57]

The Brazilian institutional and legal structure for attracting the flow of money had begun to be set up since the military regime took over. In 1965, the regime provided to foreign capital was expanded by amending Law No. 4131 of 1962, which already provided it with quite advantageous conditions, and the door was opened to the contracting of money loans between foreign and local companies. As of 1967, new measures empowered commercial and investment banks to take and repay credits to companies in the country to finance their fixed and working capital. A real capital market then emerged in the country.[58]

As bank credit to the private sector expanded, as well as extra-bank credit, underwritten by finance and investment companies,[59] foreign capital flowed in en masse. Government or international institution credits, although increasing in volume, lost relative importance to private capital. Between 1966 and 1970, their share had been 26.3% of foreign financing, but this dropped to 15.6% in 1971 and 9.2% in 1972. Meanwhile, medium and long-term foreign investment, which totaled $1.03 billion in 1966-70, grew in geometric progression: $2.32 billion in 1971 and $4.79 billion in 1972. The item with the most spectacular increase was that of loans and financing in currency, which went from 4.79 to 1,379 and 3,485 million dollars in the periods indicated. In contrast to official foreign loans, which were channelled towards investments in infrastructure and basic industries, almost all (82.3% of the total) of private capital went to manufacturing industry, particularly to the mechanical, electrical and communications equipment, transport equipment, chemicals, rubber, pharmaceuticals and metallurgy branches.[60]

It is understood, then, the need to ensure the full circulation of the capital thus invested, that is to say, to open the way to its realization. We have already pointed out that the state actively intervened in this sense, creating or subsidizing the demand (internal and external) for production. It also took care of securing investment fields abroad, through operations of state enterprises, intergovernmental credits or guarantees to private operations in Latin American and African countries. Thrown into the orbit of international financial capital, Brazilian capitalism would do everything to attract the flow of money, even if it was unable to assimilate it in its entirety as productive capital and had to reintegrate it into the international movement of capital. With this, in its dependent and subordinate style, Brazil would enter the stage of exporting capital[61], as well as the plundering of raw materials and energy sources abroad, such as oil, iron, gas.

It is natural that, on the basis of this economic dynamic, Brazil should implement a power policy. But reducing sub-imperialism to this dimension and trying to replace the very concept of sub-imperialism with that of sub-power[62] only impoverishes the complex reality we have before our eyes and does not allow us to understand the role Brazil plays today on the international plane. Brazilian sub-imperialism implies a sub-power policy; but the sub-power policy that Brazil practices does not give us the key to the sub-imperialist stage it has entered.

However, recourse to this category of international analysis brings us back to a fact that is frequently lost sight of in economic analysis: the fact that the process of internationalization of capital does not imply the progressive disappearance of national states. This perseverance is the case, first of all, because the internationalization of capital—the objective basis of the integration of productive systems—does not constitute a univocal and uniform process, free of contradictions. Assuming uniformity led, in the past, to erroneous theses such as that of super-imperialism, which Lenin and Bukharin vigorously fought against.

Bukharin, in particular, emphasized the fact that the internationalization of capital cannot be considered independently of its nationalization, establishing precisely on that contradiction the structure of the first two parts of his classic study on the subject.[63] The dialectical interplay of the internationalization-nationalization process is brought out by him, writing:

The process of organization [of the world production system]... tends to go beyond the national framework; but then much more serious difficulties arise. In the first place, it is much easier to overcome competition on the national level than on the world level (the international ententes are generally formed on the basis of already established national monopolies); secondly, the difference in economic structure and, consequently, in production costs makes ententes onerous for the advanced national groups; and thirdly, the agglomeration with the state and its borders constitutes in itself an ever-increasing monopoly, which ensures additional profits.[64]

For Bukharin, this process implied that the internationalization of economic life had as a counterpart "the tendency to the formation of closely knit national groups, armed to the teeth and ready at any moment to pounce on each other", by virtue of the subordination or absorption of the weaker or backward states to the imperialist centers.[65] The period of world history leading up to World War II confirmed the correctness of this forecast, and the new stage that opened up at the end of the conflict, which we briefly reviewed at the beginning of this paper, showed how powerful the integrating tendency of contemporary capitalism is. But, by bringing about a greater capitalist development in the subordinate zones, such as Latin America, integration also made its counter-tendencies manifest themselves with greater force in them, in particular the one that works in the sense of strengthening the national states.