DSA members have likely come across the ideas of Hal Draper, even if they are not aware that these ideas can be traced back to him. His writings in the 1960s and 1970s on socialist strategy in the trade union movement have helped to shape the work of organizations including Solidarity, the International Socialist Organization, Labor Notes, and Teamsters for a Democratic Union.

Over the last five years, Draper’s ideas have become the orientation of the overwhelming majority of DSA members active in DSA’s labor work, mainly imparted through Kim Moody’s The Rank and File Strategy, which at many points directly paraphrases arguments made by Draper. Draper’s arguments have even taken on a hegemonic perspective, meaning that they are not treated or identified as one Marxist tendency selected from among others, but rather as the common-sense understanding of what it means to do Marxist work in the trade unions.

The program promoted by followers of Draper has both a positive and a negative impact. For the majority of DSA members, the call for middle-class socialists to engage in the labor movement is a tremendous step forward. But reading carefully, we find promoted a policy of tailing the workers' movement, and most commonly a neglect of and occasionally an outright opposition to open propaganda work in the trade unions.

Our Role in a Resurgent Labor Movement,[1] the consensus resolution of DSA’s National Labor Commission for DSA’s 2021 National Convention, has much in it to commend, but is also an example of the neglect of socialist propaganda tasks in the labor movement. The document rightly calls for the fusion of the socialist and labor movements and lays out a fantastic program for how socialists can support and help to lead trade union fights. The program states that by continuing to apply the rank-and-file strategy, we will “win more workers to the cause of democratic socialism.” But at no point does it outline a program for the direct recruitment of trade unionists into DSA, think through the structures necessary to be successful in doing so, or even call for DSA comrades to recruit trade unionists. And at no point does it call for us to develop an explicit socialist line within the labor movement, instead calling for us to fuse with the rank-and-file caucuses, which are progressive and militant but not fully socialist. While the NLC consensus document does not argue against the above proposals, the neglect of them is significant.

Less frequently we also find examples of opposition to socialist propaganda work within the labor movement. Comrades are preparing a tremendous effort to support the Teamsters’ UPS contract fight. Included in the “Strike Ready DSA” toolkit is a “Picket Line Do’s [sic] and Don’ts” document that tells comrades that

Our role is to be present in solidarity with the rank and file and supportive of the strike or action, not to evangelize DSA. If a striking worker starts talking to you about M4A or Bernie Sanders, you should feel empowered to discuss that, but DSA's work is not the main focus.

Here we see an example of opposition to socialist propaganda.

Comrades are not told that our job is both to support the strike and to promote DSA, but rather only to support the strike. We are allowed to discuss not even socialism but the social democracy of M4A and Bernie Sanders, but only when the worker raises it with us. Promotion of socialism among the fighting working class, we are told, is not one of our core obligations but rather “evangelism.”

Of course, we absolutely should avoid sectarian interventions in strikes. Nonetheless, is recruiting on the strike line not one of the best ways to grow our working-class membership within the trade union movement? Rather than lecturing at comrades, why not simply outline when and how to recruit appropriately on a strike line, which absolutely can be done without coming off as sectarian when done skillfully. This small quote is just one example of a definite tendency dominant in our labor work. To those who say I am cherry-picking, when I raised the above considerations with members of the NLC I was told that “we shouldn’t fly a DSA flag at strikes,” as if this is the only way to promote socialism. This is what I mean by opposition to socialist tasks in the labor movement.

Kim Moody is even more explicit in his opposition, arguing for

a reversal of standard left conceptions of socialist politics. Rather than proceeding from a carefully worked out, analytically correct program to the dissemination of such analysis to the masses (of one sort or another), this shift in perspective would abandon the pursuit of programmatic rectitude in favor of a focus on, and engagement with, existing levels of working-class consciousness and conflict.[2]

Not a skillful combination of both socialist propaganda work and trade union agitation, but rather the “‘sacrifice' of principles and programme” by socialists working in the trade union movement.

The tendencies to neglect and to oppose socialist propaganda work in the trade union movement are not unique to the NLC or Moody, but rather can be traced to the ideas of Hal Draper. And while Draper presents his arguments as the continuation of Marxism and the Bolshevik movement, this article intends to set out that they are precisely the opposite — the neutering of the heart of Bolshevism and a false path for DSA’s work in the labor movement.

This article will show where Draper misrepresents or falsifies historical narratives and theoretical texts in order to substantiate his own theories. What makes Draper’s narratives especially dangerous is that he masks his arguments in the language and history of Bolshevism while undermining key components of Bolshevism.

Ultimately, it will be shown that Draper’s rejection of Bolshevism is an expression of the irresolute tendency of the revolutionary wing of the American middle class, which desires revolution but cannot fully accept the harsh realities of proletarian socialism. That Draper’s ideas speak to and for this wing of the middle class explains why they resonate as powerfully today as they did in the 1960s, as DSA remains largely a middle-class organization struggling to become a mass socialist party of the working class.

Four Frames for Analyzing a Marxist Tendency

There are perhaps four main ways to analyze an ideological tendency within Marxism, in order to characterize both its content and context and to thereby make a judgment about its utility to our movement.

The first and most simple frame of analysis is to compare the political prescriptions and programs that extend from the tendency, and to judge them by one’s own considerations about the question “what is to be done,” to see whether there is agreement or disagreement on the tasks at hand.

The second frame of analysis is to investigate the organizational context of the tendency. This is often referred to as Marxist haliography — the study of the lives of saints — which adds context to the previous two lenses. From which earlier tendency of the movement did the tendency under review arise, and what were the major theoretical and programmatic issues that led to the split and thereby the origin of the subject tendency as a new entity? While every theoretical or programmatic argument deserves exploration in its own right and we should avoid guilt by association, a tendency which takes a wrong stance on other key questions is liable to also be misled on the specific questions about which one is concerned.

However, the first and second frames may not reveal the underlying theoretical arguments. The third frame of analysis is therefore to thoroughly explicate the content, to explore the relationship between the tendency’s program and its understanding of the major questions of Marxist theory and history. This lens can clarify from whence the differences in political programs arise.

The fourth frame of analysis is to investigate the class context of the tendency. This is perhaps the rudest but also the most incisive lens of analysis, and also the only lens which — in employing a class analysis — is unique to Marxism. No socialist likes to be called “petty bourgeois,” but nonetheless our theoretical debates do not exist in a vacuum but are in fact highly impacted by the class pressures of society, and the ideological and economic influence of bourgeois society have more than once led Marxists astray from an unequivocally revolutionary stance. This fourth lens can help to explain why the tendency exists from the perspective of the necessary historical development of the movement, and also which forces within our movement are particularly susceptible to such a tendency today.

Having moved through all four frames of analysis, the inquisitor may then return to the first frame and review the tendency’s answer to the question “what is to be done” in a new light.

The Making of Hal Draper

Having briefly sketched the programmatic line of Draperism in the first section, we can continue to the second lens of analysis. So who was Draper, what are his ideas, and how did they become so influential a half-century later?

Hal Draper was a socialist organizer and member of several trade unions who was most notably active in the 1960s and 1970s in Berkeley, California, one of the hotbeds of the student movement and the New Left.

Draper was active in the Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL), the youth affiliate of the Socialist Party of America (SPA), during the 1930s. In 1936 the Trotskyists in the Workers Party of the United States — pursuing a policy of entryism known as the “French Turn” — entered into the SPA. James P Cannon outlines the history of this merger and the later split in the last few chapters of The History of American Trotskyism: 1928 - 1938. At the time, the left wing Militants within the Socialist Party were gaining influence, and desired a merger with the Trotskyists in order to counterbalance the right wing. A merger was agreed, but although the Socialist Party had typically allowed factions to have their own press, the Trotskyists were not allowed to retain their publications and were to join as individuals rather than as an organization. Despite this the Trotskyists took over the Socialist Appeal and quickly won influence among the Militants, especially those in the ranks of the youth wing. Draper was one of those won over to the Trotskyist wing of the SPA, along with a majority of his peers in the YPSL. He was even elected national secretary of the YPSL in 1937. In 1937 the majority of the YPSL, including Draper, split with the Trotskyists to form the Socialist Workers Party.

But it was not long before another faction fight developed. The majority of those won from the ranks of the SPA were middle class youth, and at least as Cannon and Trotsky frame it, created the basis for a petty-bourgeois deviation away from Marxism within the Socialist Workers Party, which is chronicled by Trotsky in his work In Defense of Marxism. To quote his chapter “A petty-bourgeois opposition within the Socialist Workers Party,”

Like any petty-bourgeois group inside the socialist movement, the present opposition is characterized by the following features: a disdainful attitude toward theory and an inclination toward eclecticism.

One of the major disputes was over the importance of dialectics, with the opposition either rejecting dialectics or downplaying its importance, and Trotsky highlighting the importance and relation between dialectical logic and the political and organizational tasks of the SWP, and especially the two factions’ diverging analyses of the nature of the USSR. James Burnham replied directly to Trotsky in Burnham’s article “Science and Style,” in which he both rejects dialectics and the relation between a rejection of dialectics and the opposition’s stance on political questions.

In 1940 Draper followed the opposition faction led by James Burnham, Max Shachtman, and Martin Abern in leaving the SWP to form the Workers Party, where he played a major role in editing its newspaper. While the party was not founded on Burnham’s definite rejection of dialectics, it was certainly not founded on an embrace of dialectics either, but rather apathy and eclecticism on the fundamental theoretical questions of Marxism. Burnham himself resigned from the Workers’ Party only months after the split, having come to find that “of the most important beliefs, which have been associated with the Marxist movement… …there is virtually none which I accept in its traditional form.”[3] We will revisit his further career later on.

In 1948 the Workers Party changed its name to the Independent Socialist League (ISL), and then in 1958 the ISL merged with the Socialist Party of America. Draper had not favored the merger, and in 1962 left with others to form the Independent Socialist Club (ISC) in rejection of Shachtman and others’ rightward trajectory, who had come to support the Vietnam War. In other words, Draper represented the left-wing of the petty-bourgeois opposition which had split with the Socialist Workers Party.

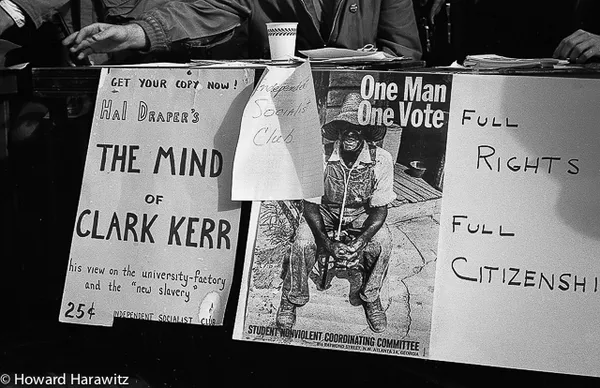

With a strong youth presence, the ISC was influential in the development of the Free Speech Movement (FSM). The FSM was a movement started at the University of California, Berkeley, of student radicals who were involved in supporting the Freedom Riders and desired to lift the restrictions on political activities that university administrators imposed on student groups. Draper served as a mentor to Mario Savio and other student leaders, giving Draper and the ISC an undeniable place of importance in the development of the New Left, the vanguard of the revolutionary layer of the middle class youth. Spreading nationally from its base in Berkeley, the ISC took on the name International Socialists (IS) in 1968. But following this period of rapid growth, Draper accused it of sectarianism and left in 1971, forming his own group which amounted to little.

Without Draper, but holding onto and implementing many of his ideas, the IS went on to form rank-and-file caucuses including Teamsters for a Democratic Union, as well as organizations including Labor Notes. In 1976 a faction of the IS left to form the International Socialist Organization, and in 1986 the remainder of the IS took on the name Solidarity. So while Draper’s later career was inconsequential, his ideas nonetheless have shaped the theory and strategy of some of today’s most prominent left-labor organizations.

In summary, we see that the organizational heritage of Draperism is a series of zig zags between three forces: Marxism, the middle class, and the workers movement. First Draper is in the Marxist wing of the Socialist Party, then the petty-bourgeois wing of the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party, then the left wing again of the Socialist Party, then the revolutionary wing of the student movement, and then finally the left wing of the labor movement. In this way Draper is a personification of the most revolutionary wing of the middle class which is not quite fully Marxist, but also the petty-bourgeoisie wing of the Marxist movement: for the middle class a step forward, for the Marxists a step backwards.

Draper on Lenin’s Theory of Consciousness and Vanguardism

Having drawn out the organizational context of Draperism, we now turn to the theoretical explication of his works. Draper’s interpretation of Lenin’s What Is To Be Done (WITBD), and especially Lenin’s theory of the development of consciousness, is at the root of how he answers the question “what is to be done” by socialists within the trade union movement.

Draper argues that WITBD has been misconstrued. He focuses on Lenin’s quotation of Kautsky on the role of bourgeois intellectuals in the development of socialist thought, which Lenin uses in highlighting the role of the party in actively promoting consciousness as against the theory of the spontaneous development of consciousness promoted by the Economists. From these arguments, Lenin calls for a party of professional revolutionaries as necessary for the evolution of the Marxist movement in Russia. In later works, Lenin writes that in WITBD he had exaggerated the need for professional revolutionaries in order to “bend the stick” away from spontaneity, which he maintains was a necessary exaggeration at the time; later, it becomes possible for a mass party which embraces not only professional revolutionaries precisely because the professional revolutionaries had built a stable party in the previous period. But Draper twists Lenin’s context-dependent critique into an argument that Lenin abandoned his entire theoretical exposition on the development of consciousness. Draper goes so far as arguing we can essentially abandon WITBD.

Disproving Draper’s narrative requires diving through a series of quotations, but the task is worth the reward. Either the arguments of WITBD are fundamental to the Bolshevik movement, or they can be abandoned entirely. So first let us address Kautsky’s argument, and then we shall address what Lenin makes of it, and to what extent he later recants his theorizations.

The offending quote by Kautsky is:

Many of our revisionist critics believe that Marx asserted that economic development and the class struggle create, not only the conditions for socialist production, but also, and directly, the consciousness [K. K.’s italics] of its necessity… …‘The more capitalist development increases the numbers of the proletariat, the more the proletariat is compelled and becomes fit to fight against capitalism. The proletariat becomes conscious of the possibility and of the necessity for socialism.’ In this connection socialist consciousness appears to be a necessary and direct result of the proletarian class struggle. But this is absolutely untrue. Of course, socialism, as a doctrine, has its roots in modern economic relationships just as the class struggle of the proletariat has, and, like the latter, emerges from the struggle against the capitalist-created poverty and misery of the masses. But socialism and the class struggle arise side by side and not one out of the other; each arises under different conditions. Modern socialist consciousness can arise only on the basis of profound scientific knowledge. Indeed, modern economic science is as much a condition for socialist production as, say, modern technology, and the proletariat can create neither the one nor the other, no matter how much it may desire to do so; both arise out of the modern social process. The vehicle of science is not the proletariat, but the bourgeois intelligentsia [K. K.’s italics]: it was in the minds of individual members of this stratum that modern socialism originated, and it was they who communicated it to the more intellectually developed proletarians who, in their turn, introduce it into the proletarian class struggle where conditions allow that to be done. Thus, socialist consciousness is something introduced into the proletarian class struggle from without [von Aussen Hineingetragenes] and not something that arose within it spontaneously [urwüchsig]. Accordingly, the old Hainfeld programme quite rightly stated that the task of Social-Democracy is to imbue the proletariat (literally: saturate the proletariat) with the consciousness [Lenin’s Italics] of its position and the consciousness of its task. There would be no need for this if consciousness arose of itself from the class struggle.

Here Kautsky is arguing that “modern socialist consciousness,” that is to say, Marxism, is developed by the bourgeois intelligentsia.

In the development of the science of socialism — for example, the analysis of the circuit of capital, the labor theory of value, the tendency of the declining rate of profit, etc — it is the political-economic scientist — generally drawn from the intellectuals of the bourgeoisie — who has the scientific training to progress theory.

Draper points to Lenin’s footnote to the above quote as evidence that he was already contradicting Kautsky even as he wrote WITBD. He quotes Lenin as writing that

This does not mean, of course, that the workers have no part in creating such an ideology. They take part, however, not as workers, but as socialist theoreticians, as Proudhons and Weitlings; in other words, they take part only when they are able, and to the extent that they are able, more or less, to acquire the knowledge of their age and develop that knowledge.[4]

But Lenin’s footnote is not at all a contradiction of Kautsky. Lenin, who uses the words “of course” to show that his explanation is obvious, is merely stating that a worker can also contribute to theoretical development, but only to the extent that they become intellectuals themselves by studying political economics, philosophy, and history. Draper only quotes the first half of the footnote, in which Lenin continues:

But in order that working men may succeed in this more often, every effort must be made to raise the level of the consciousness of the workers in general; it is necessary that the workers do not confine themselves to the artificially restricted limits of “literature for workers” but that they learn to an increasing degree to master general literature. It would be even truer to say “are not confined”, instead of “do not confine themselves”, because the workers themselves wish to read and do read all that is written for the intelligentsia, and only a few (bad) intellectuals believe that it is enough “for workers” to be told a few things about factory conditions and to have repeated to them over and over again what has long been known.[Lenin’s Italics][5]

In this second half of the footnote we see Lenin clearly link the questions of consciousness to the tasks of the RSDLP, namely, the even greater investment in propaganda among the workers. It will be shown below that Lenin’s criticisms of those who restrict literature in the unions to trade union questions only is in direct contrast to Draper’s model, which perhaps explains why Draper does not include the full quotation.

Highlighting the key role of intellectuals in the development of socialist theory is not the same as stating that they must remain dominant in the party, that workers are only to be servants to the educated elite within the party. But supporting agency and leadership for workers within the party of the present does not equate with negating the obvious fact that the main innovators of modern socialism — Marx and Engels — were themselves sons of the bourgeoisie, and that promoting socialism among the workers — as will be shown in the section “Propaganda and Agitation in the Trade Unions” — was long understood to be a question of explicit socialist propaganda.

Draper goes on to quote Lenin’s writing after the 1905 revolution, where Lenin commented on the mass upsurge of revolutionary activity, writing that

The working class is instinctively, spontaneously Social-Democratic, and more than ten years of work put in by Social-Democracy has done a great deal to transform this spontaneity into consciousness.[6]

Highlighting this quote, Draper writes that “It looks as if Lenin had forgotten even the existence of the Kautsky theory he had copied out and quoted in 1902!”

We can make two clear points here. The first is that Lenin clearly differentiates between instinct and consciousness, and links the two by “ten years of work,” that is, the active propaganda work of the RSDLP. The second point is that one can be “Social Democratic” — that is, support the program of the RSDLP — without fully understanding or developing the scientific theories of Marxian political economy, dialectics, etc. Workers under capitalism instinctively know that they get a bad deal, that the government serves the rich, etc. But that does not mean that they instinctively understand that the historic destiny of the proletariat is the overthrow of capitalism.

This points to the question of what is the meaning of class consciousness for Marxists, which is far more specific than how it is used colloquially and by most socialists today. We can break class consciousness into a number of stages: false consciousness, colloquial consciousness, low trade union consciousness, high trade union consciousness, and full class consciousness.

False consciousness means that one points to problems other than the capitalist class to explain the problems of society, for example, the ideas of patriotism, xenophobia, antisemitism, conspiracy theories, liberalism, etc. By colloquial class consciousness, I mean the way that many workers who are not at all involved in the trade union movement point to the rich as the cause of societal problems, but do not necessarily point to the struggle of the workers movement as the solution. Low trade union consciousness refers to those who understand that unions are valuable in delivering advances on questions of wages and workplace conditions, while high trade union consciousness — what Draper calls “progressive, militant trade unionism” which I explore below in the section “Draper On Marxism and Trade Unions” — refers to the need for militant unions to play a role in challenging corporate power in society at large.

But full, Marxist consciousness goes beyond even high trade union consciousness. Marxist theory asserts that it is the historical destiny of the proletariat to overthrow the bourgeoisie in a revolution which establishes a workers’ state as a means to implement socialism. A worker who is not conscious of the historical destiny of their class, ie. who is not a Marxist, is not class conscious, at least not fully. And while “progressive, trade union consciousness,” can develop within the workers movement on its own as the struggle for wages and working conditions meets the obstacles of bourgeois society at large, full class consciousness is based on the study of economics and history, which can only be achieved by being exposed to explicit socialist propaganda. The workers movement cannot become class conscious in the Marxist sense without the workers being “imbued” upon by the socialists; this is why the bowing to spontaneity and tailing of the workers movement is so dangerous to Lenin, and why he sees the need to base the socialist movement on a dedicated core of socialist propagandists.

Returning to our explication, Draper next turns to some quotes from Lenin in the anthology 12 Years, which he also attempts to use to show that Lenin has rejected his arguments in WITBD. As mentioned above, Lenin writes that he had exaggerated his writings on the importance of professional revolutionaries in order to ‘bend the stick’ against the then-current fad of spontaneity and horizontalism. But for Draper,

It is obvious that the reference to “exaggerated ideas” is an admission of a degree of incorrectness, even if the confession simultaneously maintains that the incorrectness was pardonable.

But Lenin does not admit to incorrectness in this passage. In fact, he highlights that the fact that the perspective — the need for a party based on a core of professional revolutionaries — is no longer necessary to highlight is precisely because WITBD served its purpose and the party evolved to a higher stage based on the stability built by these party cadres. Lenin writes in the preface to 12 Years that

The basic mistake made by those who now criticise What Is To Be Done? is to treat the pamphlet apart from its connection with the concrete historical situation of a definite, and now long past, period in the development of our Party…Today these statements look ridiculous, as if their authors want to dismiss a whole period in the development of our Party, to dismiss gains which, in their time, had to be fought for, but which have long ago been consolidated and have served their purpose…

Unfortunately, many of those who judge our Party are outsiders, who do not know the subject, who do not realize that today the idea of an organization of professional revolutionaries has already scored a complete victory. That victory would have been impossible if this idea had not been pushed to the forefront at the time, if we had not “exaggerated” so as to drive it home to people who were trying to prevent it from being realized.[All Lenin’s emphasis][7]

Draper continues, arguing that in this article Lenin was “pigeonholing [WITBD] as of historical interest only,” claiming that “It would be hard to imagine any more telling refutation… …unless perhaps Lenin had staged a bonfire of all extant copies of WITBD.”

On the question of Lenin’s theory of spontaneity and consciousness, in 12 Years Lenin points to the unity of the arguments of WITBD and the 1902 Draft Party Program of the RSDLP, which holds that

The emancipation of the workers must be the act of the working class itself… Russian Social-Democracy undertakes the task of disclosing to the workers the irreconcilable antagonism between their interests and those of the capitalists, of explaining to the proletariat the historical significance, nature, and prerequisites of the social revolution it will have to carry out, and of organising a revolutionary class party capable of directing the struggle of the proletariat in all its forms.[8]

What can “disclosing” imply if not that the workers themselves cannot achieve knowledge of their own historic destiny on their own, but rather that it is the task of Social-Democracy to reveal it to them?

In summary, in 12 Years Lenin argues that the prescription of a party composed only of professional revolutionaries is no longer appropriate in 1907, but that it was essential during its time and that it is no longer essential precisely because it has succeeded. While putting his organizational formulations on the role of professional revolutionaries in context, he again defends his conception of the relationship between consciousness and spontaneity.

Draper misconstrues Lenin’s contextual review and defense of an organizational plan as not only a rejection of that plan, but also a rejection of the entirety of WITBD and especially Lenin’s formulation on spontaneity and consciousness.

The question of the relation between spontaneity and consciousness is at the very core of WITBD. In the conclusion to that text, Lenin summates his argument and directly answers the question “what is to be done” by breaking the history of Russian Marxism into four periods.[9]

The first period embraces about ten years, approximately from 1884 to 1894. This was the period of the rise and consolidation of the theory and programme of Social-Democracy. The adherents of the new trend in Russia were very few in number. Social-Democracy existed without a working-class movement, and as a political party it was at the embryonic stage of development.The second period embraces three or four years—1894-98, In this period Social Democracy appeared on the scene as a social movement, as the upsurge of the masses of the people, as a political party. This is the period of its childhood and adolescence…

The third period, as we have seen, was prepared in 1897 and it definitely cut off the second period in 1898 (1898-?). This was a period of disunity, dissolution, and vacillation… …The proletarian struggle spread to new strata of the workers and extended to the whole of Russia, at the same time indirectly stimulating the revival of the democratic spirit among the students and among other sections of the population. The political consciousness of the leaders, however, capitulated before the breadth and power of the spontaneous upsurge [my emphasis]; among the Social-Democrats, another type had become dominant — the type of functionaries, trained almost exclusively on “legal Marxist” literature, which proved to be all the more inadequate the more the spontaneity of the masses demanded political consciousness on the part of the leaders.

We firmly believe that the fourth period will lead to the consolidation of militant Marxism, that Russian Social Democracy will emerge from the crisis in the full flower of manhood, that the opportunist rearguard will be “replaced” by the genuine vanguard of the most revolutionary class. In the sense of calling for such a “replacement” and by way of summing up what has been expounded above, we may meet the question, What is to be done? with the brief reply: Put an End to the Third Period.“

So we see that the question of “what is to be done” is a question of overcoming the lowering of political consciousness of the leadership before the spontaneous rising of the masses. Draper rejects Lenin’s theorization precisely at its most critical point.

Lenin’s defense of the role of the conscious vanguard based on his theory of consciousness is also in consonance with the influence of the Narodnik revolutionary Chernshevky’s earlier work What Is To Be Done?, from which Lenin took his title. Chernyshevky’s allegorical work, written in a Tsarist prison, is focused on the impact of a series of hyper-conscious individuals whose own enterprising and self-disciplined spirit empowers them to impact those around them. In the work the novel’s female protagonist, Vera, founds a sewing cooperative but waits until it is successful before informing her seamstresses that they are in fact co-owners of the business. Vera is herself influenced by the extreme Rakhmetov, the son of a noble who abandons his wealth to haul barges, studies obsessively, and adopts a puritanical way of life, even eventually sleeping on a bed of nails to challenge his self-discipline. Lenin, himself the son of a lower noble, began reading Chernyshevky during his exile after leading student protests his freshman year, was heavily influenced by Rakhmetov, apparently copying his model of strenuous daily physical exercise. No one familiar with Chernyshevky’s What Is To Be Done can fail to see the replication by Lenin of these themes in his political analysis of the tasks necessary before the RSDLP.

Far more could be written about the dialectic between consciousness and spontaneity or the conscious vanguard and the working masses beyond what Lenin and Kautsky had to say on the matter. The question of the dialectic of consciousness and matter, of conscience agent and rising masses, of subject and object — the materialist dialectic — is at the very heart of Marxist philosophy and was explicated at least as early as Marx and Engels’ The Holy Family in 1845 and sharpened in the Theses on Feuerbach and The German Ideology. Marxism approaches the question of consciousness and masses not as a dichotomy, but rather dialectically — in other words, by understanding both the initial opposition and the subsequent unity of the two categories. First the socialist movement and the workers movement develop side-by-side; then they merge as the socialists propagandize among the masses and raise the best layers of the workers movement up to the level of worker socialist intellectuals.

Draper on Marxism and Trade Unions

Armed with an understanding of Draper’s “innovations” on the plane of theory, we can now turn to Draper’s writings on practical work in the trade unions.

Draper’s series of lectures to the members of the International Socialists in the fall of 1970, “Marxism and the Trade Unions,” lays out formulations which are copied almost line-by-line in Kim Moody’s The Rank and File Strategy. Draper begins the lecture series with the absurd claim that,

Essentially, no Marxist group has ever carried on any systematic revolutionary work in trade unions.We have here, then, a subject which is paradoxical. On the one hand, by its very nature, it raises the basic questions of Marxism, the relationship of Marxism to the labor movement. On the other hand, in a century nothing has been written on it and revolutionary Marxist work in trade unions could be put into a nutshell.

Draper goes on to review the work of the Communist Party and the TUEL in the AFL of the 1920s. I have already demonstrated that the TUEL was explicitly guided by and in support of the Bolshevik model of organizing in the trade unions and based on Lenin’s theory of consciousness.[10]

One need only turn to Lozovsky’s pamphlet Lenin and the Trade Union Movement which was distributed by the TUEL to counter Drapers’ claim. Lozovksy was hardly a nobody, but rather an old Bolshevik who served as head of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profintern) from 1920 to 1924. One can also turn to Zinoviev’s The Tactics of the Communist International from 1921, which held that

The new tactics of the Communist International are characterized by the following… To the masses... down into the depths of the proletarian and semi-proletarian masses. Participation in the minor daily struggles, even if carried on for the most insignificant improvement of the standard of living. Participation in all workers’ organizations from the workers’ councils to the athletic clubs and musical societies. Persevering propaganda for the ideas of the dictatorship of the proletariat in all these organizations. Conquest of the majority of the working class for Communism. Systematic, determined, and persistent preparation of the working masses for the coming struggles. Careful work in the creation of illegal organizations. Patient, indomitable work for the arming of the workers. The establishment of strong, independent communist parties, purified of opportunists, centrists and semi-centrists. Above all ... Conquest of the trade unions.[11]

So we see that the entire Third International was from its founding oriented toward struggle in the trade unions, with the approach of both participation in the daily struggles and the promotion of socialist propaganda. This is not to mention the numerous articles and works by Lenin,[12] Trotsky,[13] Foster,[14] Cannon,[15][16] and countless other Marxists who were active in trade union work prior to 1970 defend the same strategy. Drapers’ baseless claim that “nothing has been written” on Marxism and the trade unions is an attempt at erasure of the voluminous work which had been written, but which contradicted his own ideas.

He goes on to misrepresent the TUEL to an even greater extent than Moody does 30 years later. He creates a false history where the TUEL began as an independent rank-and-file movement for limited demands, before being taken over by the big, bad Communist Party and pushed in too extreme a direction. One need only look at the very first issue of the TUEL’s Labor Herald to see that the TUEL defended Communist lines and championed the dictatorship of the proletariat from the beginning and through its successes in the labor movement, and not at some later stage.

From Draper’s bad history grows his bad policy. He outlines how his organization did trade union work and socialist party work side by side.

Within the framework of the trade union, we behaved as progressive, militant trade unionists… …but in our newspaper, we said everything. The combination of these two things represents an all-sided and balanced revolutionary approach to the problem of trade union work.

But this framing represents a dichotomous approach rather than a dialectical approach. Compare this to the Communist Party, which used the TUEL to engage in militant and explicitly socialist work in the trade unions. Here the two categories are not engaged side-by-side, but rather are combined.

For Draper the revolutionary approach means explicitly not bringing up socialism openly within the trade unions. He correctly poses the question, asking

How do you combine two things: (1) the most advanced political organization, even if it’s small, and (2) the participation in struggle with the broadest possible organization of the masses in movement.

But then he goes on to give the wrong answer,

Which brings us to the formula I gave you last time, and which I will end by repeating: “What you want to do is get moving, as a class, the broadest possible movement of the masses against the capitalists, the state, and therefore also the trade union bureaucracy itself.

This formulation implies the liquidation of the socialist forces into the workers movement and denigrates the task of building up the revolutionary party itself. How is the revolutionary movement to draw new recruits from the workers' movement and gain influence for socialism within the trade union movement — not to mention win dominance of the unions — if it hides its politics behind economistic trade union demands?

Of course, the socialists do want to get the class moving, but the Bolshevik model puts the emphasis in reverse — the essential ingredient for the workers’ movement to transcend both spontaneous upsurges and limited economic demands is a strong socialist political leadership which provides continuity and direction.

Again, we return to the question of the development of consciousness. If the workers can develop socialist consciousness spontaneously, without the guidance of a socialist force, then there is no need. But if not, then the intervention of the party is necessary.

Propaganda and Agitation in the Trade Unions

This formulation is essentially a question of how to balance propaganda work and agitational work.

In 1891 Plekhanov’s “Tasks of the Social Democrats in the Fight Against Famine In Russia” provided a solid conception of the need for propaganda and agitation and the relationship between the two. Like Moody, Plekhanov begins by highlighting the central role of worker consciousness, and highlights that promoting this consciousness is the main goal of the socialists. He writes that propaganda means communicating “correct views,” that is, a fully Marxist conception, to “tens, hundreds, and thousands of people,” thereby recruiting worker-socialists who will be “the best leaders of the revolutionary masses, the most reliable officers and non-commissioned officers of the revolutionary army.” But Plekhanov continues, finding that

people possessing correct views only become historical figures when they have direct influence on public life. And influence on the public life of modern civilised nations is unthinkable without influence on the masses, i.e. without agitation…Agitation is just like propaganda, but propaganda taking place under special conditions, which compel even people who would not pay attention to them in normal times to listen to the words of the propagandist…

If it were necessary to further explain the mutual relationship between agitation and propaganda, I would add that the propagandist gives many ideas to one individual or several individuals, but the agitator gives just one or only a few ideas to a whole mass of people.[17]

Plekhanov explains that propaganda is the direct spread of socialist ideas to those who are open to them, which the socialist movement carries on all the time. On the other hand, agitation is engagement of the masses on the issues that are raised through the course of events, which allows the socialists to help lead the masses in fights around limited demands. When socialists successfully use agitation the results are two-fold: securing victories that are useful on the path to socialism and winning concrete reforms which demonstrate that the socialist movement is immediately beneficial to the working class. Plekhanov sums up the joint tasks of propaganda and agitation on the specific issue of the Russian famine, writing that

Having counted its forces and distributed them appropriately, revolutionaries get to work. In all layers of the population they, by means of oral and printed propaganda, they publicize the correct perspective as to the cause of the present famine. Where the masses have still not matured sufficiently for an understanding of their message, they give them, so to speak, object lessons. They appear wherever they protest, they protest together with them, they explain to them the sense of their own movement and with this increase their revolutionary preparedness. In this way, the spontaneous movement of the masses gradually merges with conscious revolutionary movement.[5]

So we see that the correct relation between propaganda and agitation is the key to spreading revolutionary consciousness among the workers, the merging of the masses with the conscious elements.

Plekhanov is writing at a time when the socialist movement is transitioning from propaganda to propaganda and agitation. Small propaganda circles, mainly built around revolutionary students or graduates, have been recruiting small numbers of workers to join them in the study of socialist theory. Plekhanov’s text is an attempt to direct the socialist movement on how to move beyond propaganda work into agitational organizing around the issue of the day, a famine that is sweeping Russia. But in calling for the need to conduct agitational work, Plekhanov never calls for the abandonment of propaganda.

Martov’s 1896 work “On Agitation” built on Plekhanov to explain the necessity of agitational work and mass struggle for the education not of a narrow group of socialist cadre but for the entire working class, provideing important insight into the significance of the economic struggle in the development of workers' consciousness.[18] Martov correctly identifies that the internal logic of capitalism brings workers into struggle against the bosses, and that the workers’ movement takes on political forms when its fight for economic reforms is halted. He demonstrates that it is necessary for the workers to go through the school of economic struggle in order to realize the need for a revolutionary struggle. But Martov is talking about the masses, not about individual workers; he never takes the position that individual workers cannot be convinced of the need for a revolution based on socialist propaganda.

Moving beyond the early propaganda circles, the first agitational work of the Russian Marxists largely consisted of factory exposures and appeals to strike. One early effort was spearheaded in part by a young Zinoviev, himself a factory worker at the Putilov plant. Leaders of the St. Petersburg League of Struggle were almost all arrested, but nonetheless, not long after their arrest the League helped to lead the first multi-factory strike in Russian history, in May of 1896.[19]

Writing in The Tasks of the Russian Social-Democrats in 1897, Lenin explicated the relationship between propaganda and agitation.

The socialist activities of Russian Social-Democrats consist in spreading by propaganda the teachings of scientific socialism, in spreading among the workers a proper understanding of the present social and economic system, its basis and its development, an understanding of the various classes in Russian society, of their interrelations, of the struggle between these classes, of the role of the working class in this struggle, of its attitude towards the declining and the developing classes, towards the past and the future of capitalism, an understanding of the historical task of international Social-Democracy and of the Russian working class. Inseparably connected with propaganda is agitation among the workers, which naturally comes to the forefront in the present political conditions of Russia and at the present level of development of the masses of workers. Agitation among the workers means that the Social-Democrats take part in all the spontaneous manifestations of the working-class struggle, in all the conflicts between the workers and the capitalists over the working day, wages, working conditions, etc., etc. Our task is to merge our activities with the practical, everyday questions of working-class life, to help the workers understand these questions, to draw the workers’ attention to the most important abuses, to help them formulate their demands to the employers more precisely and practically, to develop among the workers consciousness of their solidarity, consciousness of the common interests and common cause of all the Russian workers as a united working class that is part of the international army of the proletariat.[20]

Again, Lenin never called for the lowering of propaganda work among the workers in favor of agitation, but rather agitation to compliment propaganda. In fact, when the Mensheviks put forward a limited approach on socialist tasks in the trade union movement at the fourth RSDLP conference in 1906, the Bolsheviks fired back in a resolution. The resolution states that

the party should make every effort to educate the union workers, in the spirit of a clear understanding of the class struggle and of the socialist tasks of the trade unions, in order by its activity to gain actual control over the unions.[21]

This is far from behaving as merely “progressive, militant trade unionists.”

So we see that Lenin’s views on the importance of both intellectual propaganda work for the purpose of building socialist cadre and mass agitational work for the purpose of leading the masses in struggle were not restricted to a few passages in WITBD, but rather were the heritage of the entire RSDLP in the transition in the 1890s from the circles to mass work and were again defended after the 1905 uprising. These methods of building agitation on top of a strong basis of propaganda work directly contrast with the proposals laid out by Draper and later by Moody.

The Class Basis of Economism and Draperism: Workers, Students, and Stooges

Continuing on from our exposition of questions of theory and history, we can now progress to the final analytical lens: the class basis of Draperism and the class basis of its continued appeal within the socialist movement.

In refrain, socialist organizations do not exist in a vacuum, but rather within our class society and therefore within the violent conflicts between classes.

In his conclusion to WITBD, Lenin explains the class basis of economism. He points to two sources based in two classes - the under-development of the newly-rising workers movement, and the under-development of socialism among the layers of the intelligentsia, the majority of which had only recently been exposed to Marxist ideas and mainly through the discourse of “legal Marxism.” And “legal Marxism” points to a third class source, the Tsarist regime.

I address the rise of “legal Marxism” in my book, Student Radicals and the Rise of Russian Marxism, in the section “The First Marxist Students.” During the second half of the 1890s the Marxists were engaged in a heated debate with the Narodniks. As the government saw the Narodnik terrorists as a greater threat, they allowed some Marxist criticisms of Narodnism through the censors; the government was also seeking to promote the development of capitalism in Russia, and so some Marxist economic works which acknowledged the necessity and benefit of capitalist development in Russia were allowed as well. This collection of work came to be known as ‘legal Marxism.’ Lenin recalls that

In a country ruled by an autocracy, with a completely enslaved press, in a period of desperate political reaction in which even the tiniest outgrowth of political discontent and protest is persecuted, the theory of revolutionary Marxism suddenly forces its way into the censored literature and, though expounded in Aesopian language, is understood by all the ‘interested.’ The government had accustomed itself to regarding only the theory of the (revolutionary) Narodnaya Volya as dangerous, without, as is usual, observing its internal evolution, and rejoicing at any criticism levelled against it. Quite a considerable time elapsed (by our Russian standards) before the government realised what had happened and the unwieldy army of censors and gendarmes discovered the new enemy and flung itself upon him. Meanwhile, Marxist books were published one after another, Marxist journals and newspapers were founded, nearly everyone became a Marxist, Marxists were flattered, Marxists were courted, and the book publishers rejoiced at the extraordinary, ready sale of Marxist literature.[22]

Although Marxist critiques of Narodnism and Marxist economic works were for a time allowed to pass the censor, explicitly revolutionary literature or political critiques of the Russian system remained confined to the underground. This division of Marxist literature into legal and illegal was to have a profound impact on the development of the movement. Lenin notes how widespread was the penetration of Marxist literature in the second half of the 1890s, writing in What Is To Be Done?

We have noted that the entire student youth of the period was absorbed in Marxism. Of course, these students were not only, or even not so much, interested in Marxism as a theory; they were interested in it as an answer to the question, “What is to be done?”, as a call to take the field against the enemy. These new warriors marched to battle with astonishingly primitive equipment and training.

Although Marxist ideas spread rapidly, this did not mean that the students had become fully-fledged Marxists. Students and academics were more easily exposed to the legal writings, while only the committed revolutionaries were steeped in the full Marxist account. Ironically it was long periods in the Tsarist jails or in Siberian exile which was particularly conducive to the theoretical development of the underground revolutionaries. By the 1907 conference of the RSDLP, the combined 140 delegates had spent 138 years, 3 ½ months in jail and another 148 years, 6 ½ months in exile, roughly one third of their combined 942 years tenure in the Social Democratic movement.[23]

So we see that the majority of the intelligentsia, and namely the students, were exposed to the limited Marxist ideas - mainly of an economic nature - which were temporarily allowed through the Tsarist censor by way of an oversight. In contrast, the majority of the leadership of the RSDLP was exposed to “illegal Marxism” through the underground. In fact it was often precisely the removal and detention of Marxists from the movement by the Tsarist regime which allowed RSDLP leaders the time to advance their own theoretical studies. Lenin, for example, began reading Chernyshevksy and then Plekhanov’s translations of Marx after being expelled from Kazan University for his activity as a student organizer.

Strong parallels can be drawn to the proliferation of Marxist theory today, based on similar but not identical class pressures.

Many students and recent graduates who have come to socialism in the last ten years, who make up the majority of DSA members, are interested in the ideas of socialism to answer the question “what is to be done,” and not because they have been won over theoretically. The majority of our comrades also have almost no experience in the labor movement, and also have generally very limited experience in recruiting members to socialism, not to mention recruiting them on a picket line.

In addition, the university professors of today promote their own version of “Legal Marxism,” what can be termed “Academic Marxism.” Any professor who quotes Marx once in the affirmative is suddenly dubbed a “Marxist professor,” even if they only subscribe to the most limited conception of Marxist theory. It is not far easier to receive a PhD or a tenured position if one limits oneself to analyzing capitalism or Das Kapital than if one goes around promoting the dictatorship of the proletariat? The most radical Marxists have historically been purged, for example Angela Davis who was fired by Ronald Reagan from her position as a professor of philosophy at UCLA.

In fact, my first run in with Draperism was on that same campus, where I attended a “History and Theory of Marxism” class under Robert Brenner, an editor of Solidarity’s Against The Current. Seeing that the syllabus only covered Das Kapital, I asked Brenner if we were going to be studying dialectical materialism in the class. He replied that he “did not believe in that metaphysical mumbo-jumbo.” I was further disappointed that Brenner did not even assign readings from Das Kapital, but only his own notes on the chapters. Perhaps Brenner had only available a first edition, because then he could be excused for failing to note that in Marx’s Afterword to the Second German Edition Marx very explicitly outlines his dialectical method.[24]

Putting Brenner aside, let us turn to the third class force which weighs upon the socialist movement, the capitalist state. Again, Das Kapital is illuminating; in the Preface to the First German Edition, Marx points out that

In the domain of Political Economy, free scientific inquiry meets not merely the same enemies as in all other domains. The peculiar nature of the materials it deals with, summons as foes into the field of battle the most violent, mean and malignant passions of the human breast, the Furies of private interest.[25]

In understanding the class history of Draperism, the furies of private interest are mediated through the capitalist state - the servant of the bourgeoisie’s collective private interests - and its war on Marxism.

Drawing a few passages from a history of capitalist counter-revolution which I have developed elsewhere, we can note a few facts which roughly sketch how the CIA and FBI have intervened in the Marxist movement and even in the realm of socialist theory.

Building on earlier work against radicals and union organizers, in the 1950s and 1960s the FBI ran “COINTEL” (counter-intelligence) disruption programs against the Communist Party, the Black Panther Party, the Socialist Workers Party, and other radical groups. The programs were not based on prosecuting criminal activity, but rather were designed to neutralize perceived political threats. In Hoover’s own words:

The purpose of this program is to expose, disrupt, and otherwise neutralize the activities of the various New Left organizations, their leadership and adherents. We must frustrate every effort of these groups and individuals to consolidate their forces or to recruit new or faithful adherents.[26]

Writing on the SWP COINTEL program, Chomsky writes that the program

reveals very clearly the FBI’s understanding of its function: to block legal political activity that departs from orthodoxy, to disrupt opposition to state policy, to undermine the civil rights movement.[27]

So we see that the state clearly admitted to the purpose of disrupting the left. One of the main strategies for pursuing this policy was disruption from the inside.

In the 1960s, the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) membership ranged from around 600 to 1,000 members at any given time; one judge found that - from 1960 to 1974 - the FBI had some 300 paid informants in the membership, and an additional 1,000 non-member paid informants which included janitors in the SWP’s office buildings, employers, and other civilians with insight into the operations of the organization.[28] Typically, infiltrators were marked either by their disinterest in political theory and interest in violent action - symptoms of a desire to provoke violence for entrapment purposes - or were marked by an overzealousness in politics and a tendency towards hairsplitting - symptoms of a desire to fuel divisions and provoke splits. In one of the most extreme examples, Malcolm X’s personal bodyguard of seven years was an undercover agent.[29] The FBI also placed bugs and wiretaps in SWP offices, conventions, and National Committee meetings.[30]FBI personnel also consistently broke into and burglarized SWP offices as part of COINTEL. During the period of 1960 to 1974, the FBI made at least 204 entries into SWP offices and 4 entries into SWP members’ residences, all without warrants.[31]

In addition to harassing SWP members on an individual basis, the FBI worked to undermine the organizing capacity of the SWP as a whole.

Some informants were able to achieve leadership positions, where they frustrated effective organizing, blocked successful recruitment, and even argued for lower dues payments in order to weaken the party’s finances.[32] One particular tactic was the use of racist “poison pen” letters, allegedly from white SWP members, which were sent to black SWP members to divide the membership.[33] Legal cases were also used in order to keep organizations including the SWP on the defensive; final legal charges were often minimal, but the resource burden of the case often left the organizations as shells of their former selves.[34] The FBI also played a significant role in promoting splits in the SWP, and generally in working to lower the morale of party members by criticizing party leadership.[35]

We do not exactly know the extent to which the FBI merely fueled existing splits or by developing its own theoretical line; certainly the FBI had enough agents to do so.

While the FBI was focused on suppressing Marxism domestically, the CIA pursued a global approach.

The Congress of Cultural Freedom(CCF) was one ambitious CIA project - funded from 1950-1967 - which supported progressive or anti-Stalinist socialist publications and other programming throughout the Western world, including Partisan Review, Der Monat, The New Leader, Minerva, and Encounter. The CCF was led by reformist socialists and labor leaders in the Second International tradition, including anti-Communist AFL leader Irving Brown, and anti-Marxist German SPD leader Carlo Schmid, and funded and managed from behind the scenes by the CIA. The CCF was an important site of reunification for wayward wings of the early American communist movement, as veterans of the right opposition and left opposition were united in their opposition to Moscow.

A former member of the left opposition involved in the formation of the CCF was James Burnham. As mentioned above, Burnham had been a leading member of the American Trotskyist movement, until he sided with Max Schactman in a factional fight with Cannon and Trotsky. Although Burnham and Schactman split from the Socialist Workers Party to form the Workers Party, not long after Burnham resigned from the Workers Party, having come to reject dialectical materialism.

Burnham then joined the Office of Strategic Services - the predecessor to the CIA - and was tapped after the war to head the Political and Psychological Warfare division of the Office of Policy Coordination at the newly formed CIA. He worked with CIA officer Michael Josselson to found the CCF, a veteran of psychological warfare in the US Army.[36] Later, Burnham would go on to co-found William F. Buckley’s National Review in 1955, along with William Casey, later Reagan’s campaign manager and after that Reagan’s CIA director.

Notable ‘socialist’ texts linked with the CCF include Crosland’s The Future of Socialism - which argues against Marxism and the expansion of government control of the economy, and Daniel Bell’s The End Of Ideology - which argues that political ideology has become irrelevant. Crosland’s text was foundational in the ideology of the post-war revisionist wing of the Labour Party, which eventually rejected nationalization as a key tenet. Staffed with ex-socialists heavily steeped in Marxist theory and organizational strategy, the CIA not only backed revisionists and moderates in the socialist movement, supporting right-wing factions within socialist parties, but orchestrated a literary war on Marxist theory itself.

Finally, the security state was itself aware of the value of Leninism in particular and in fact appropriated Leninism for its own uses. I have shown in my work that CIA advisor Frank Barnett developed a capitalist appropriation of Leninism as early as 1958 in his chapter “What Is To Be Done” American Strategy in the Nuclear Age.[37] This Leninism-for-capitalists was then promoted by the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1959 to 1962 in their National Strategy Seminar series - organized by Barnett - which functioned as a “Cold War university.” I go on to show that the infamous Powell Memorandum - which many authors point to as the guiding document of the Reagan Revolution and the rise of neoliberalism, was directly influenced by Barnett’s Leninist ideas.

Returning to our subject, the points on the security state are summarized. I do not go so far as to suggest that Draper was himself an FBI agent or CIA officer; the full extent of the capitalists intervention in Marxism may never be known. But what is clear is that (1) the security state worked actively to disrupt the Marxist left, including by fueling splits and seeding groups with undercover agents (2) that Burnham and others were or became agents of the security state, (3) that the security state intervened on questions of socialist theory, and (4) that the security state was aware of the particular value of Leninism. Overall, the point is that the American capitalist class has waged a clandestine war on Marxist theory. The best most militant and theoretically serious wings of Marxist were violently suppressed, while revisionists were offered shelter and even subsidies by the bourgeois state, allowing them to fill the vacuum left by the marginalized genuine heirs of the Bolshevik tradition

What is clear is that the class pressures weighing on Draper’s work in the 1960s have much in common with the class pressures which weighed on the Russian Marxist movement at the end of the 19th century. A new (or renewing) workers movement was still in the years of immaturity, a quickly-radicalized student movement was more eager to take action than to firmly grasp theoretical questions, and the agents of the capitalist state were intervening to disrupt the movement in general with the impact of suppressing the most revolutionary aspects of Marxism in particular. And can we not say that there is commonality with the state of our recently reinvigorated movements of workers and of socialists today?

For a Bolshevik Rank-and-File Strategy

The ideas of Draper are being promoted in DSA’s labor work through Moody’s The Rank and File Strategy. Without citations to a degree which borders on plagiarism, Moody echoes Draper’s claim that “Lenin revised his view allowing for the “spontaneous” development of socialist consciousness.” He also takes a similar line on the TUEL, arguing that “the greatest weakness of the TUEL was that it was controlled top-down” by the Communist Party, and arguing that it should have taken an “independent rank and file leadership.”[38] Although Moody echoes many of the ideas of Draper, Draper develops his theories to a greater extent and often takes more extreme stances, making him more useful as a foil on questions of theory and history.

In arguing against Moody and Draper’s works, it should be noted that there is a difference between rank-and-file work in general and the specific Bolshevik formulations on rank-and-file work and the Draperist line on rank-and-file work. An argument against The Rank and File Strategy is not an argument against rank-and-file work, but rather a call to set it on the correct basis.

In seeking a way to bridge the middle class socialist movement and the labor movement, Draperism in fact leads to the reinforcement of this divide. For socialists, a program of “progressive, militant trade union” work does bring them within the labor movement. But when a worker within the unions is recruited, what becomes of them? In their trade union work, in their daily work-life, they are not to raise socialism among their coworkers and in their union meetings, but rather “progressive, militant trade unionism.” The assumption that socialists are not workers, the call to hide one's own socialist views in the trade union movement, leads to the failure of workers who are socialist to function effectively. How can socialism spread rapidly in the union movement if workers do not advocate - are encouraged not to advocate - spreading socialism in the union movement and recruiting their most sympathetic peers?

Of course, it is not true that no DSA comrades or even Draperists themselves have never raised socialist views within their unions or recruited workers to socialism. But the point is that Draper actively argues against and provides theoretical backing to a policy which at best fails to draw out the most direct ways to do so, and at worst actively argues against them by misleading comrades on programmatic, theoretical, and historical questions.

I have already laid out my proposals for DSA’s work in the labor movement in my article “100 Years On, The TUEL Is A Strong Framework For DSA’s Labor Work,”[10] so I will not restate specifics. However, I will conclude by saying that Marxist Unity Group has made a helpful contribution in framing this approach as a “Partyist” approach to labor work, and largely affirming the spirit of my article in their Labor Strategy Position Paper.[39] The position paper correctly asserts that “our focus now should be working to strengthen and deepen the rank and file strategy by politicizing our labor work.” It would be valuable if the “partyist” wing of DSA raises a “partyist” line in our labor work by developing an organized intervention targeted at pivoting the NLC in the right direction in the months following the national convention.

To set ourselves on the right path programmatically, we must identify and uproot the ideology of Draperism which has gained almost hegemonic status in our ranks. In that Draper and Moody attack WITBD on precisely the question that Lenin uses to attack the economist trend, they are themselves a revival of economism. However, the second coming of economism comes wrapped in the shroud of Lenin and is all that much more challenging to uproot. But the answer to the question “what is to be done?” remains the same:

Put an end to the third period (again)!Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- https://s3.amazonaws.com/actionkit-dsausa/dsa/2023_DSA_Convention_Compendium.pdf ↩

- Kim Moody. “Unions, Strikes, and Class Consciousness Today.” 2014 ↩

- https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/burnham/1940/05/resignation.htm ↩

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/ii.htm ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1905/reorg/i.htm ↩

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1907/sep/pref1907.htm ↩

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1902/draft/02feb07.htm#bkV06P027F01 ↩

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/concl.htm ↩

- https://working-mass.com/2022/10/18/opinion-100-years-on-the-tuel-is-a-strong-framework-for-dsas-labor-work/ ↩

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/zinoviev/works/1921/11/ci-tactics.html ↩

- Should Revolutionaires Work in Reactionary Trade Unions? https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1920/lwc/ch06.htm ↩

- Communism and Syndicalism https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1931/unions/index.htm ↩

- The Principles And Program of the TUEL https://www.marxists.org/archive/foster/1922/principles.htm ↩

- “Our Aims and Tactics in The Trade Unions” https://www.marxists.org/archive/cannon/works/1924/unions.htm ↩

- Two Articles on the Slogan ‘Rank-and-File Leadership https://www.marxists.org/archive/cannon/works/1932/apr/clarandf.htm ↩

- “The Origins of Bolshevism: Plekhanov's ‘The Tasks of the Social-Democrats in the Famine.’” (https://www.workersliberty.org/story/2004-09-24/origins-bolshevism-plekhanovs-tasks-social-democrats-famine). ↩

- On Agitation - Martynov 1896 https://drive.google.com/file/d/1nxdlHwklI4wNynbSxwswgdi2HNcMyWcR/view?fbclid=IwAR29F7yLzOgl8bMfcFqPTSAA48HN9L5RONZAIU25bHkEoRZnLczCVWTqbKY ↩

- Cliff, Tony. 2002. Building the Party: Lenin 1893-1914 Chapter 2 (https://www.marxists.org/archive/cliff/works/1975/lenin1/index.htm) ↩

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1897/dec/31b.htm ↩

- Quote from Lozovsky https://www.marxists.org/archive/lozovsky/1924/14.htm ↩

- Lenin, Vladimir I. (1902a). What Is To Be Done?: Burning Questions Of Our Movement. Lenin’s Selected Works, Volume 1, pp. 119 - 271. (https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/). ↩

- Trotsky, Leon. (1907). 1905. Haymarket Books, Chicago. 2016. Page 291. ↩

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/p3.htm ↩

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/p1.htm ↩

- Jayko, Margaret. 1988. FBI on Trial: the Victory in the Socialist Workers Party Suit against Government Spying. New York: Pathfinder Press. Page 17. ↩

- The War on American Socialism: A Primer on Modern and Contemporary Counter-Revolution. Page 26. https://pdfhost.io/v/mTJj1IydA_ULA_Thesis_Final_Draft ↩

- Jayko, 69. ↩

- Marx, Gary T. 1974. “Thoughts on a Neglected Category of Social Movement Participant: The Agent Provocateur and the Informant.” American Journal of Sociology 80(2):413. ↩

- Jayko, 95. ↩

- Jayko, 109. ↩

- Jayko, 79. ↩

- Jayko, 88. ↩

- Churchill, Ward. 2004. “From the Pinkertons to the PATRIOT Act: The Trajectory of Political Policing in the United States, 1870 to the Present.” CR: The New Centennial Review 4(1): 55 ↩

- Chomsky, Noam and Edward S. Herman. 1973. Counter-Revolutionary Violence: Bloodbaths in Fact and Propaganda. Andover, MA: Warner Modular Publications. 118-120 ↩

- https://newcriterion.com/issues/2002/9/the-power-of-james-burnham ↩

- Barnett, Frank R. 1960. “What Is to Be Done?” in Walter F. Hahn and John C. Neff, eds., American Strategy for the Nuclear Age (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books). (https://archive.org/stream/americanstrategy00hahn/americanstrategy00hahn_djvu.txt). ↩

- https://solidarity-us.org/rankandfilestrategy/ ↩

- https://cosmonautmag.com/2023/03/letter-marxist-unity-group-labor-strategy-position-paper/ ↩