What can Victorian table-turning tell us about Marx’s theory of value? Ian Wright investigates.

The “Gypsy” Table

In the early 1980s, my grandparents lived in a small council flat on the 8th floor of a high-rise tower block in Sheffield. Occasionally, at family gatherings in their home, but only when pestered, they would reluctantly fetch what my grandmother called her “gypsy table.”

The gypsy table was a small, wooden table, with a circular top about waist high, with space for, at most, one teapot and some cups. It had three turned legs that were arranged in a tripod for stability.

But, this was no ordinary table. It was a magical table. And, it was magical because it could host spirits.

To evoke a spirit, two or more people would place their hands upon it, linked, as in a seance, but standing rather than sitting. Then, one of my grandparents would speak aloud, into the aether, and invite a spirit to join us.

We would fall quiet, in anticipation, looking at the table for any signs of life.

“Spirit, show us a sign if you are there.” And, there would be silence. And, everything would be still.

“Spirit, we await you.” And, nothing would happen.

But then, almost imperceptibly, the gypsy table would stir, and slowly, very slowly, rock back on two of its tripod legs, raise its third, and then slowly rock forward to resume its rest position. The air became electric with the arrival of the spirit.

Ensouling Objects

Humans have been summoning spirits into inanimate objects for millennia.

The ancient Egyptians summoned Ka, which seems to have meant “living breath,” of their dead ancestors into the body of statues. They paraded the statues at festivals so the dead, with painted eyes wide open, saw the mortal world again.

Newly crowned pharaohs, to prevent spiritual interference from dead political enemies, commanded the noses of their enemies’ statues be chopped off to prevent their spirits from breathing, forcing the Ka to depart.

But, not just dead ancestors. Gods inhabited temple statues. To maintain their divine presence, they were tended daily. A priest performed the “opening of the mouth” ceremony, touching the statue’s mouth, eyes, nose, and ears with ritual implements to give it the power of breath, sight, smell, and hearing. On auspicious days, the temple priests placed the ensouled statue on a boat and sailed it along the Nile in full view of assembled crowds. When the boat approached the river bank, worshippers gathered to ask the god questions and gain spiritual guidance. The god, trapped in the statue, able to see and hear but not talk, communicated by rocking the boat, back and forth, on the water.

The ancient Greeks maintained the presence of gods within their temples with animal sacrifices, prayer, and dedications. In the Iliad, petitioners ask the statue of Athena to save the city but she declines by turning her head away. The Greek Magical Papyri, a collection of manuscripts dating from 100 BC onwards, contains several spells for ensouling statues. Neoplatonic theurgy, the system of magic developed by Iamblichus and his followers in Late Antiquity, describes the practice of ensouling statues. And, the early Christian polemicist, Tertullian, writing in the 2nd century AD, disapporingly reports of pagans conjuring spirits that communicate through the movement of stools and tables.

The Table that Walked and Talked

So, although I didn’t know it at the time, my grandparents and I were participating in a very ancient practice.

Once the gypsy table was ensouled, it could answer questions, rocking once for “yes” and twice for “no.” We could ask it anything. It could foretell the future, and reveal secrets.

And, if we were lucky, the table walked across the carpet floor, by rocking back to raise a tripod leg, then rotating like an inclined wheel, to place its legs back on the carpet, a few inches further forward.

Despite the evidence of our senses, most of us thought this must be impossible. Wooden tables cannot walk or be possessed by unseen spirits. The skeptics amongst us immediately asked my grandparents to remove themselves as, clearly, they were moving the table with their hands.

Yet, even when operated by the skeptics themselves – the table still moved.

I remember one family member upturning the table to inspect its underside to try to discover a hidden mechanism. I tried it with my little sister. Just two young children linking their hands upon it. No one else had their hands on the table. We too felt and saw the table move.

It was magic.

Victorian Table-Turning

Or was it?

My grandmother claimed that her family had acquired the table from a traveling gypsy. Gypsies, even in the 1980s, had the reputation of being magical folk.

This story fired my childish imagination. I imagined a colorful horse-drawn caravan, a distant relative entering, and an illicit exchange with an old crone sitting within its shadows.

But, the truth is probably more mundane.

In the Victorian era, occasional tables with three legs were very popular, mass-produced commodities. They were marketed as “gypsy tables” because they were small and easily transported.

This marketing exploited the Victorian obsession with “table tipping” or “table-turning,” which is a practice that seems to have originated, at least in modern times, in America’s Spiritualist movement.

In 1848, the teenage Fox sisters reported poltergeist activity in their house in New York. Eyewitnesses reported tables spontaneously making knocking sounds, rocking back and forth, and even levitating many feet off the floor. A year after the sisters first reported their encounters with spirits, they publicly demonstrated table-turning before an audience at the Corinthian Hall in New York. This was a sensation. Newspapers rapidly spread the word.

Infant mortality was high; life expectancy was low. People were hungry for contact with the spirit world to help with their grief and loss. Quite naturally, the spiritually hungry or the just plain curious, attempted to replicate the phenomenon at home. And, it worked. The tables really did move. Table-turning became a craze.

The fad spread to England when an American traveling medium advertised their demonstrations on the front pages of the Times. Within the year, table-turning had become fashionable throughout the land. The upper classes held “tea and table-turning” parties while the lower classes commandeered their kitchen tables. Even Queen Victoria and Prince Albert joined in.

England’s tables were moving, animated by invisible ghosts or spirits.

Marx on Table-Turning

Table-turning was so popular that even Marx and Engels had mentioned it. Engels briefly mentions table-turning in his “Dialectics of Nature,” where he satirizes modern spiritualism.

Marx mentions table-turning in the Communist Manifesto and again in the first paragraph of his famous chapter on the “Fetishism of Commodities” in the first volume of Capital. Here’s the full quote:

So, what is this change that occurs in the table as “soon as it steps forth as a commodity?”

Well, a wooden table, in the context of a market economy, acquires new properties. The table may be exchanged for 100 loaves of bread, one engagement ring, 1.5 porcelain tea sets, and so on. The table, in other words, acquires the property of exchangeability, and the table’s relative price anticipates these exchange ratios.

But, why do commodities have prices? Marx points out that the activities of independent, private producers must be coordinated. In a market economy, this is achieved by feedback in the form of transfers of money that flow in the opposite direction to the transfer of commodities. Activities in undersupply sell at higher prices, and get rewarded with higher money rewards. Conversely, activities in oversupply sell at lower prices and get punished with lower money rewards. Producers are therefore forced to switch from unprofitable to profitable activities. The economy, in a spontaneous and unplanned manner, continually and roughly achieves a social division of labor that produces the correct quantity of commodities to meet monetary demand. Effective demand, however, is skewed by class inequality. Although this division of labour succeeds in reproducing class society, it always fails to meet many real human needs.

So far, so good. That’s why commodities have prices at all. But, why do some cost more than others? What determines relative prices?

Marx, like the classical economists before him, understood that prices fluctuate with supply and demand. But what needs explaining is the relatively stable structure of prices over longer periods of time . Why do planes always cost more than pens? Why do sofas typically cost about the same as computers?

Marx answers that a capitalist economy, due to the competitive scramble for profit, tends towards but never fully reaches an attractor state where prices are proportional to the socially necessary abstract labour-time required to make them. In a hypothetical equilibrium state without profit and rent, and where supply perfectly equals demand, then prices will perfectly represent abstract labour-time. Marx names this dynamic the “law of value.” And so a plane almost always costs more than a pen because it requires much more labour-time to make it.

A wooden table, therefore, acquires not one, but two new properties, when it “steps forth as a commodity”: an exoteric property, which is exchange-value or its price; and an esoteric property, its actual value, which is the quantity of labour-time to produce it, which Marx calls “value” and (for clarity) I will subsequently call its “labour-value”. A commodity’s labour-value is the hidden regulator of its exchange-value and therefore its market price.

“Phantom-like” Objectivity

The wooden table acquires new properties when it functions as a commodity. But, why does Marx say that an ordinary table becomes “transcendent?” Why is this “far more wonderful” than table-turning?

Marx, at least in translation, writes of labour-value being “embodied” in commodities, and therefore commodities are “merely congealed quantities” of the expenditure of abstract labour. But Marx denies that labour-values are literally, and therefore physically, embodied in commodities, like wine poured into a bottle. Marx says:

Marx also asserts that the labour-value of an already produced wooden table, stored unsold in a warehouse, will change immediately if society adopts new labour-saving techniques to make it. Marx observes:

Marx is clear. The labour-value of any commodity is the labour-time that counterfactually would be used up if that commodity was produced right now, today. This seems, on the face of it, like spooky “action at a distance” because the unsold commodity, sitting on a shelf, hasn’t changed at all.

In consequence, the labour-value of a commodity is indeed strange, even “transcendent.”

During a table-turning seance, a spirit inhabits the body of the wooden table. The table, therefore, acquires a new property of being ensouled, and the new power of communicating with people. The very same table, in the context of a market economy, also acquires a new property, of being a labour-value, with the new power of exchangeability with all other commodities. In both cases, no matter how hard we look, even if we turn the table this way and that, we will never be able to see the spirit or the labour-value hiding within it. These properties become – in some sense – embodied within the table and yet – in another sense – are entirely absent, invisible to our senses. Just as the hidden spirit ultimately animates the table its hidden labour-value ultimately animates its price. The secret that makes all commodities exchangeable is something hidden, something occulted, a spectral or phantom-like objectivity – called value.

An ensouled table may appear wondrous. But a table, as an economic value, has a ghostly property equally real and unreal. This magic of the commodity is “far more wonderful” because it is far more powerful.

Victorian Scepticism

In antiquity, belief in gods and spirits was widespread, whereas commodity production was sporadic and limited. By the Victorian era, this situation had reversed. The emergence of capitalism, and the scientific revolution, weakened the hold of religion and superstition. Ancient belief in ensouling clashed with scientific skepticism, even when repackaged in a modern form by American spiritualists.

In consequence, many scientists, doctors and the clergy – exemplars of Victorian respectability and common sense – turned their skeptical attention to table-turning. Indeed, even Arthur Conan Doyle felt compelled to investigate, the creator of the fictional paragon of Victorian rationalism.

After controlling for trickery and deception, our common-sense heroes proposed various theories. Skeptical of heresy rather than the spirit world, the clergy denounced it as a form of devil worship. The more scientifically minded turned to invisible forces, such as the recently discovery of electromagnetism, galvanic forces, or even animal magnetism, the force that was believed, by some, to explain hypnosis.

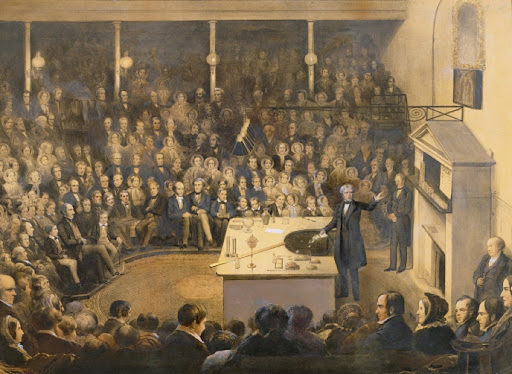

By the Victorian era, the scientific community, was fully reconciled to the existence of invisible forces. Newton’s successful theory of gravity proposed an invisible force that influenced the motion of bodies at a distance without an intervening mechanical medium of transmission. Michael Faraday’s pioneering experiments at the Royal Institution in London revealed the existence of electric and magnetic forces that extended into empty space. If humanity had for millennia failed to notice such things, perhaps there were many more. Other, more speculative, hypotheses were advanced to explain table-turning, such as ectenic or ectoplasmic force, a precursor to the theory of psychokinesis, and Odic forces, named after the god Odin, which was a vitalist analog of electromagnetism.

No one denied the reality of the phenomenon in these investigations. The skeptics merely differed regarding the true cause. That’s because tables really did turn – even when the skeptics were in control.

Victorian England was faced with an epidemic of ghostly spirits, specters, and apparitions. They did not emerge from the London fog or out of the corner of the eye, but they came in full view, manifesting in the homes of anyone inclined to invite them.

Michael Faraday, Scientist, and Ghost Hunter

This was a minor ideological crisis. Who could get to the bottom of this? What person had the right combination of expertise in mysterious phenomena yet sufficient scientific acumen? Victorian society needed a real-life Sherlock Holmes.

They found him in Michael Faraday. His ingenious experiments had discovered new hidden forces of nature. His public lectures had captivated young and old alikeat the Royal Institution. He could induce magnetic fields by harnessing the power of electricity. He built and demonstrated marvelous rotary devices that seemed to move of their own accord. His scientific credentials were impeccable.

Faraday was pestered with hundreds of letters, from all walks of life, asking him to investigate the mystery of table-turning. For example, William Hickson, editor of the Westminster Review, wrote:

“Now, if Newton was wise in asking himself why does the apple fall, may we not, with due modesty, ask his successors, why does the … table turn?”

Faraday eventually relented. He began by attending seances to witness table-turning for himself, organized by his friend the Reverend John Barlow, Secretary of the Royal Institution. He became convinced that the phenomenon was real, not mere trickery. He set to work. And, that meant applying the scientific method.

The Crucial Experiment

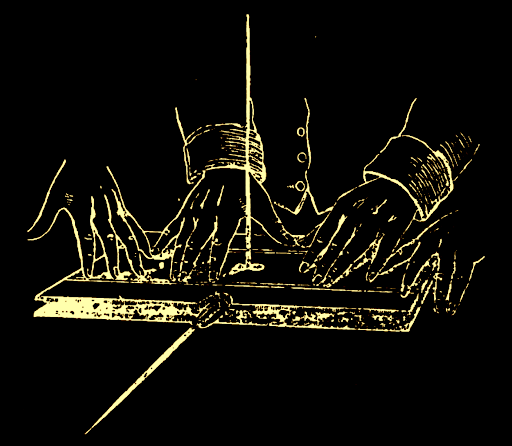

He covered a table with different insulating materials to prevent electrical or magnetic forces from interfering. Next, Faraday asked volunteers to perform the seance in laboratory conditions. The table still moved. Electromagnetism, as an explanation, was ruled out.

In 1853, Faraday conducted an ingenious experiment. He placed glass rollers between two small boards that were fastened together so the upper board would slide left and right before the lower one moved. Any lateral force on the upper board would transmit to the lower with a lag. He attached an upright haystalk that clearly waved with any lateral movement. Then, he placed the entire apparatus on top of the wooden table.

His volunteers began the seance. And, yes, the table still moved. But, before the table moved, the haystalk waved, indicating that their hands caused the table to move.

Faraday concluded that the volunteers were deceiving themselves by unknowingly moving their hands. The subconscious caused table-turning. In fact, as soon as the participants realized that they were moving the table, as soon as they became conscious of what they were doing, then the spell was broken, the magic died, and the table became absolutely still.

Faraday communicated his findings in a letter to the Times. He declared that table-turning was a psychological, not a supernatural, phenomenon, due to a “quasi-involuntary muscular action.” Faraday, as he wryly observed, had “turned the tables on the table turners.”

Hypnosis

Faraday credited his contemporary, William Carpenter, a physician and scientific skeptic, for the theory that explained his experimental results.

Carpenter noted that bodily responses can be automatically caused by ideas. For example, many people spontaneously salivate if they imagine sucking a lemon. Carpenter explained many types of anomalous phenomena – such as automatic writing, water dowsing, the movement of the planchette on a Ouija board – in terms of an “ideomotor effect”, where, in the appropriate social setting, a subject’s ideas can cause their hands to move, but without them being aware of it. Carpenter’s theories contributed to the first neuropsychological theories of hypnotic suggestion.

Modern theories of hypnosis continue to emphasize that our subjective beliefs can affect what we perceive to objectively be the case. Bottom-up sensory processing is under-determined without top-down non-sensory organizing principles. In other words, the empirical world literally leaves some “wiggle room” for ideas to create wiggles. In this view, hypnotic phenomena don’t involve unusual or altered states of consciousness, but are merely particularly dramatic and confounding examples of how we normally function in the world.

Faraday’s explanation – that table-turning is self-hypnosis induced by engaging in a shared social practice – can also explain the more ancient phenomenon of ensouled objects. Many ancient people believed that the cosmos is the body of a supreme immaterial spirit, transcendent and immanent, that animates the lesser gods who in turn animate the material world. The whole world was already ensouled. So, temple statues were not miraculous anomalies, but rather localized and intense manifestations of a universal principle.

If Faraday was right, then humanity has been deceiving itself for millennia by unconsciously projecting its own enchanted belief systems outwards onto the physical world as a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy, confirmation bias, or mass hypnosis. The statues, tables, talismans, crystal balls, and the smoke that curled from incense burners, didn’t host actual spirits, but our own imagination.

Faraday chalked up another success for Victorian science. The haunting epidemic could now be safely ignored, relegated from the supernatural to the merely entertaining.

The Law of Gravity and the Law of Value

Could Victorian science also solve the mystery of the haunted commodity with its “phantom-like” or “ghostly” objectivity?

This was certainly Marx’s intention. He had asserted that a labour-value was a property of a commodity, but could not be found in it. He also asserted that its labour-value could change due to changes in the productivity of labour occurring hundreds of miles away. Marx therefore needed to explain himself to his readers.

This was no easy matter. The first part of Capital, where Marx explains value, is difficult. Marx reworked it many times. To try to explain himself, Marx drew an analogy with Newtonian gravity. For example, he states that:

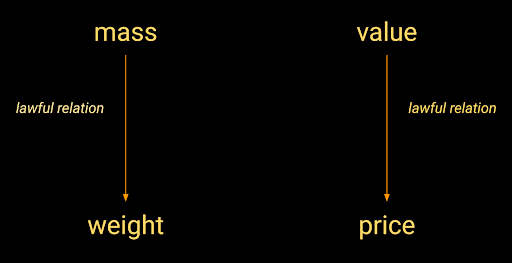

The law of value is like the law of gravity. A bird flies, and a shelf stays up, but gravity is always working away behind the scenes, so eventually the bird will fall, and the books will tumble. Similarly, prices may deviate significantly from their underlying labour-values, but this can’t persist for too long because real material costs of production eventually assert themselves in the market, often in the form of a sudden crisis.

Marx also compares [labour-]value to mass:

“As [labour-]values, all commodities are only definite masses of congealed labour time.”

Furthermore, Marx also draws an analogy between exchange ratios and weight. For example, 100 loaves may weigh the same as 1 kg of iron because they have the same mass. Similarly, 40 yards of linen are worth 2 coats because they both have the same labour-value. After making this point, Marx remarks:

Field Properties

Marx didn’t pursue his analogy further. We can.

An object with mass has a weight in virtue of the local gravitational field in which it’s placed. If we change the surrounding field by transporting the object to the moon, then the very same mass has a different weight. Weight cannot be found in the object – no matter how closely we examine it – because weight is a force that acts upon the mass. Even though we can’t find weight in the mass, nonetheless, weight is a property of it.

Does a mass really “have” a weight? We say it does, although that’s not fully accurate, because “weight” is really a relation between a mass, a local gravitational field, and the law of gravitational attraction.

So, we have a property of an object that is not a property of the object in itself. Call this kind of property a “field property.”

It was Faraday who, in 1849, first coined the term “field” to explain the results of his experiments with magnetism and electricity. For example, Faraday placed a paper sheet, coated with a thin layer of melted wax, on a bar magnet and then gently peppered the wax with iron filings. The magnetic force aligned the filings to reveal the invisible lines of force. He let the wax cool to yield a frozen picture of the magnetic field.

Another example: Faraday built a spherical capacitor made of two brass spheres, one placed inside the other. He induced a positive charge on the outer sphere by charging its inner sphere with an electric current. He then measured the electrostatic force in the gap between the spheres, which demonstrated the existence of an invisible electric field that extended beyond the metal itself.

Just as a mass in a gravitational field is subject to a force called weight, a metal in a magnetic field is subject to a magnetic force, and a charged particle in an electric field is subject to an electrostatic force. Modern physics takes these field ideas much further.

The ancient Greek philosopher, Thales, proposed “that all things are full of gods” (or spirits) after observing the power of magnets to move iron, and the power of amber, when rubbed with animal fur, to pick up straw. These spirits animated passive matter. Faraday’s breakthroughs explained the same phenomenon, not with anthropomorphic spirits, but with invisible fields.

“Conditions of Production” = Technology Field

Faraday had exorcized spirits from statues, tables, and also electromagnetic phenomena. Could Faraday also help to exorcize the ghostly objectivity of Marx’s values? Undoubtedly he could have if there ever had been a chance meeting in a London pub, because Marx – by drawing analogies with mass, weight, and the law of gravity – was already flirting with the concept of a field.

So, let’s complete this exorcism.

Typically, a field associates a quantity with every point in a physical space. But, the space doesn’t have to be spatial. Consider the state of technology in the world right now, at this moment in time; and think of the enormous variety of methods we employ to produce the enormous variety of goods and services we consume. Now, imagine this economic state of affairs as a vast input-output network with nodes that represent commodity-types and directed arrows (which connect one node to another node) to represent the fact that one commodity-type gets used up when producing another.

Mathematically, this network is a connected commodity-space. Each node is not a point in physical space, but a “point” in commodity-space. We can associate a vector, which is simply a list of numbers, with each point in commodity-space.

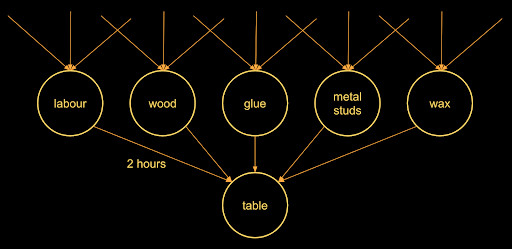

For example, consider the node labeled “small, three-legged wooden table”. Say the first number associated with this “point in commodity-space” is the average labour-time directly supplied to produce this type of table. Let’s say that’s two hours because, averaged over all the different concrete methods of producing this kind of table, it takes two hours to transform raw materials into the finished article. Say that the second number is the average quantity of wood directly used up. And, let’s say that’s 40 board feet of timber. And, the third number is the average quantity of glue, the fourth number is the quantity of metal studs, and so on, and so on. And, we repeat this exercise for every commodity in the entire world.

This enormous network is what Marx consistently calls the “conditions of production.” It’s a social, not a physical field. We’ll call it the technology field.

To begin with, assume the technology field is static. Of course, it does change. Nodes and arrows wink in and out of existence with every birth or death of a commodity-type or change in the methods of production. Yet just as physicists consider static fields before generalizing to dynamic fields, so shall we.

Value as a Field Property

Now consider a three-legged wooden table that’s just been produced, ready for shipping to a warehouse. What is its labour-value?

Start at the table’s node in the technology field and add to a running total the direct labour-time used to produce it. Then follow, backward, all the input arrows to this node. For example, we trace the 40 board-feet of timber back to its node and add the direct labour-time used-up to produce this quantity of timber to our running total. We do the same for the glue, and the metal studs, and so on, each time adding to our running total.

We don’t stop there. We need to consider the commodities indirectly used up to produce the timber, the glue, the studs, and so forth. We recursively trace all the input arrows backward in the technology field, adding each direct labour time to our running total as we go. Eventually, this process will asymptote to a definite, finite value, which represents the total direct and indirect labour-time used up to produce this kind of table. This is its labour-value.

This means, quite simply, that a labour-value is a field property.

The labour-value represents what Marx calls, following the Ricardian socialist Thomas Hodgskin, the total “coexisting labour” supplied to produce the table, and by coexisting he means all the labour supplied, in all the different branches of production, that cooperatively produces the table and all the necessary direct and indirect inputs. A labour-value is a fraction of the social working day. In economics, the procedure we’ve described is known as vertical integration, and we compute labour-values by inverting matrices that represent the conditions of production.

Now, in electrostatics, the potential energy of a charged particle in a field is the work that would need to be done to move it from an infinite distance away to its present location in the field. The labour-value of a commodity in a technology field is the work that would need to be done to produce it from scratch. Labour-values and potential energy are therefore very similar. Both are instantaneous properties of “objects” in a “field” that have mathematical representations in terms of integrals or sums over fields.

And this is why Marx is inspired when he draws his analogy with gravity. A commodity has a labour-value in virtue of the technology field in which it’s embedded. A labour-value cannot be found in the commodity – no matter how closely we examine it – because labour-value is a field property.

Just as an electric field governs the movement of a charged particle due to the laws of electrostatics, and a gravitational field governs the movement of masses due to the laws of gravity, a technology field governs the trajectory of a commodity’s market-price due to the law of value. In all cases, an underlying field property manifests as the potential or actual motion of those things under its influence. It’s the hidden principle of movement and animation.

So, does a commodity really “have” a labour-value? Yes, but we have to clarify what we mean.

A labour-value is a relation between a commodity-type, a local technology field, and the law of value. A commodity really is “congealed labour time” because it is material wealth that, if destroyed, requires a definite quantity of labour-time to recreate, a quantity that depends on the technology field in which the commodity is embedded. The destruction of the commodity is identically the destruction of its value. But, that value was never “in” the commodity.

A labour-value is not literally embodied in a commodity, like wine poured into a bottle. It is more like a genie in a bottle, except the genie is not a real spirit. It is a hidden, typically invisible property of our own social practices that manifests, in a distorted and fetishized form, as exchange-values in the market.

“Spooky Action-at-a-distance”

Faraday’s field concept also helps to exorcise those interpretations of Marx’s theory that see spooky action-at-a-distance.

Again, let’s return to the wooden table, which now has been stored in a warehouse, unsold, for over a year. In the meantime, the technology field has changed. The world now employs more efficient techniques to make these tables. As a result, the labour-value of the table has decreased.

The labour-value of the table stored in the warehouse immediately alters with every change in the technology field, without the need for any causal process or medium of transmission, for the simple reason that its labour-value is a field property. The change actually occurs in the technology field. Nothing happens in the material body of the commodity. But, such field changes immediately begin to have causal consequences.

A change in the technology field modifies the attractor state of the law of value. Markets start to converge to the new attractor. The price of unsold tables, and newly produced tables of the same kind, start to decline relative to other commodities – because less of society’s labour-time is now needed to produce them. If demand for such tables remains constant, then some proportion of society’s working day will eventually be reallocated to other activities.

The change in the labour-value of an already produced commodity no more requires “action at a distance” than does the change in status of a person from married to divorced due to a legal act that happens to occur many hundreds of miles away. In both cases, the full causal consequences do not immediately manifest.

Labour-values have a phantom-like objectivity, not because they are “insubstantial”, ineffable or pure social constructs, but because they are hidden properties of the totality of our objective conditions of production that, in ordinary life, only manifest to our senses in the distorted and mysterious form of exchange-values.

Modern Ensouling

Victorian skepticism, especially Faraday’s contributions, revealed that ensouled objects are creations of our own minds. In 1888, the Fox sisters admitted that table-turning was a hoax. The occult power that sent tables rocking and knocking across two continents had a human, not a supernatural, origin. Spirit summoning was either a conscious lie to deceive others, or an unconscious lie to deceive oneself. The old enchantments were dying.

But, Victorian scepticism did not extend to the value-form. As Marx observed of the religious world:

A fetish is an inanimate object that we worship because we think it’s inhabited by a spirit. The emerging science of economics was fully enchanted by the fetish of the value-form, thinking it transcendentally real, rather than an immanent creation of our own social activity. As Marx wrote:

We inherit this bourgeois hubris of scientific and commercial rationality that thinks itself free of all superstition. Yet capitalism has its own darker enchantment. For we daily perform a mass ritual that ensouls every object and activity in the world with a property called economic value. The movement of these numbers, not under our conscious control, governs our lives just as much as the ancient gods once did. We are not yet free of spirits but remain haunted by them.

My grandparents were full of ghost stories. They always believed there was more to reality than met the eye. Still, my grandfather never trusted the gypsy table.

In fact, his first act, after he’d recovered from the death of my grandmother, was to take an axe to the table, chop it to pieces, and burn it. At the time, I was shocked by the act and the belief in the supernatural that motivated it.

Now I’m older and less judgemental. My grandfather simply wanted to be free of the spirits that haunted his home.

Further Reading

Capital, Volume I. Karl Marx, 1867.

Capital, Volume III. Karl Marx, 1894.

Faraday, The Life. James Hamilton, Harper Collins, 2002

Substance or Field, a note on Mirowski, Ch.6 of “The Law of Value”. Ian Wright, PhD thesis, 2015.