Concessions obtained by financiers must be safeguarded by ministers of state, even if the sovereignty of unwilling nations must be outraged in the process. Colonies must be obtained or planted, in order that no useful corner of the world may be overlooked or left unused. -Woodrow Wilson[1]In politics nothing radically novel may safely be attempted -Woodrow Wilson[2]

There is much talk at the present time of standing by the president. I am willing to stand by the president if he stands for the things I want, but when I look at the gang that stands behind the president, I know it isn’t my crowd. -Eugene Debs, March 1917, on Woodrow Wilson, the American Socialist

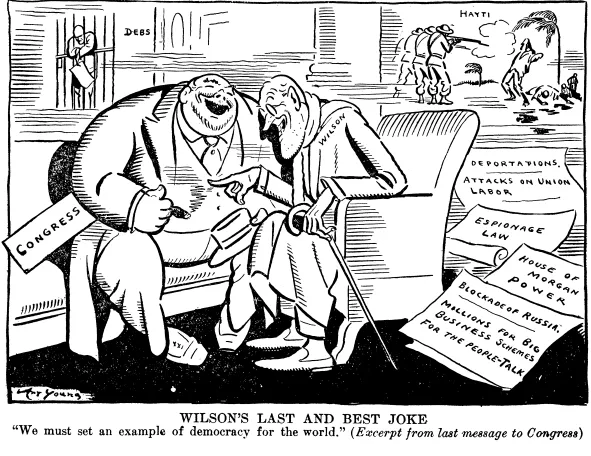

In the March issue of the Atlantic, staff writer and ex-George W. Bush speechwriter David Frum attempted a rehabilitation of President Woodrow Wilson. Frum laments progressives who have scorned the 28th President as a racist and the conservatives who have termed him a dictator. Frum’s article, although historically misleading, is revealing for what it leaves out. Among those elisions are Wilson’s record of imperialism in Latin America, the commercial reasons for U.S. entry into World War I, the intervention of the Allies to crush the Bolsheviks, and his role in crushing socialist and labor movements at home.

That Frum would write an apologia for Wilson is unsurprising. Like Frum’s former boss, Wilson presided over a time of hysterical super-patriotism (Bush’s term had “freedom fries”; Wilson’s had sauerkraut renamed to “liberty cabbage”), a severe curtailment of civil liberties, and U.S. invasions of smaller and weaker countries. His article reads like a coded defense of Bush. By absolving one he hopes that you will look upon the other more favorably. It is up to psychologists and psychiatrists to determine if this is a symptom of a guilty conscience.

Frum writes Wilson’s “commitment to self-determination did not apply to the small countries of this hemisphere: A U.S. intervention he ordered in Haiti in 1914 extended into a 20-year occupation.” Frum glosses over what really happened in Haiti. First, U.S. marines invaded to steal the gold reserves from the Haitian national bank. Then, the U.S. launched a full occupation that claimed 10,000 Haitian lives and restored forced labor to the country for the first time since the Haitian Revolution had abolished slavery. There was no idealistic purpose for the occupation; it was done solely to ensure that Haiti kept paying its creditors in a timely fashion. The occupation ended not for any great moral reason but because the Great Depression made it too costly to keep the marines in Haiti.

Wilson’s attitude towards all of Latin America, not just Haiti, was one of superiority and condescension. Publicly he announced “the United States will never again seek one additional foot of territory by conquest.” In that same 1913 speech he promised that “morality and not expediency” would guide U.S. foreign policy. His private feelings, however, were quite different. These were exemplified by his statement to the ambassador to England: “I am going to teach the South American Republics to elect good men!”[3] Of course what Wilson, who said of big business, “I am not afraid of any corporation, no matter how big”, meant by “good men” and what poor Latin American peasants meant were very different things.[4]

The Dominican Republic, which borders Haiti on the island of Hispaniola, was another Latin American country that saw U.S. military intervention under Wilson’s rule. The marines landed in 1916 ostensibly to protect American interests during a period of civil unrest. Far exceeding that mission, they ended up staying for eight years, placing the country under virtual military dictatorship. During that time marines regularly mistreated captured Dominican guerillas and when U.S. forces left, they forced a humiliating treaty on the nation entitling the U.S. to all revenues from their customs office. One of the members of the army trained by the U.S. during the occupation was future Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo.

In his piece, Frum claims that Wilson “resisted military intervention in the Mexican Revolution.” This is wholly at odds with the facts. In 1914 the U.S. invaded and occupied the port of Veracruz in an incursion that cost hundreds of Mexican lives. The invasion was the result of sheer arrogance. U.S. sailors had been arrested in Veracruz. They were released unharmed but when a U.S. naval commander demanded a 21-gun salute, the Mexicans wouldn’t comply. This slight was apparently enough to justify an invasion and occupation, which assuaged the U.S.’s wounded pride.

Nor was this the last bit of U.S. interference in Mexico while Wilson was in office. First there was the futile attempt to capture Pancho Villa that succeeded only in inflaming Mexican sentiment (including that of forces fighting Villa) against the United States. Then, during World War I, Wilson contemplated occupying Tampico and Veracruz to ensure a steady supply of Mexican oil for the war effort and forestall any nationalizations of American owned property, but this never occurred.

I want the people of America to understand that if we have war with Mexico, our boys will not be fighting for their country. They’ll be fighting for the Wall Street interests that own four billion dollars’ worth of property in Mexico for which they paid not one hundreth part. -Eugene Debs[5]

Wilson inherited the U.S. occupation of Nicaragua from his Republican predecessors. Nevertheless, he did nothing to end it and the occupation continued until 1925. In 1916 Wilson’s Secretary of State negotiated the Bryan-Chamorro Treaty, which turned the country into a virtual protectorate of the United States. One section mirrored the Cuban Platt Amendment, and would have allowed for U.S. military intervention at any time. The Senate Foreign Relations committee blanched at that provision and excised it, but that Wilson would push for it in the first place speaks volumes.

When discussing Wilson’s role in Europe, Frum writes that “he tried to mediate a negotiated end to World War I.” The truth is that Wilson’s efforts to secure peace in Europe consisted of threats of military force against Germany. His diplomat Edward M. House proposed a conference to be attended by all belligerents. House stated that “if it failed to secure peace, the United States would leave the Conference as a belligerent on the side of the Allies…” This bellicosity was hardly the tactic of a disinterested peacemaker.

Frum writes that Wilson was “forced into” World War I. This is a curious formulation. The German Empire did not invade the United States or attack any military targets. There was no Pearl Harbor-style assault. U.S. military leaders of the time thought it was absurd to consider Germany a major threat. Wilson’s stated casus belli was the campaign of submarine warfare by Germany, yet neither side respected the neutrality of the seas. The British set up a naval blockade around Germany and created a blacklist of any ships that traded with their enemies. What, then, brought the U.S. into the war?

In a postwar speech, given in St. Louis in 1919 Wilson himself said: “This war, in its inception was a commercial and industrial war. It was not a political war.” It was industrial rivalry and a desire to protect trade to Allied Powers of France and Great Britain that prompted U.S. entry to the war, not any high minded reasoning about making the world “safe for democracy.” Indeed, if it was a war for democracy, why did the U.S. join the empires of Great Britain and France, who held colonies containing millions of people? There was no democracy in colonial Algeria, Indochina, India, Burma et al., yet the U.S. didn’t go to war to make them safe for democracy. Anti-war Senator George W. Norris correctly pointed out “we are going into war on the command of gold. We are going to run the risk of sacrificing millions of our countrymen’s lives in order that other countrymen may coin their lifeblood into money.”

After World War I, the U.S. sent troops to Russia in support of the White Armies battling the Bolsheviks. About 12,000 troops landed at Archangel and Vladivostok in an attempt to prop up an alternative to the Soviets and secure Allied munitions stockpiles. They failed at both but did engender hostility from the Soviets that lasted for decades. Nikita Khrushchev reminded the U.S. “Never have any of our soldiers been on American soil, but your soldiers were on Russian soil.”

Wilson’s war coincided with massive repression of the Left and antiwar movements. The Espionage Act, passed by Congress and signed by Wilson, targeted those during wartime who “shall willfully cause or attempt to cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty in the military or naval forces of the United States, or shall willfully obstruct the recruiting or enlistment service of the U.S.'' This overly broad statute was used to convict Eugene Debs after his antiwar speech in Canton, Ohio. It was also used to indict socialist cartoonist Art Young for his allegedly seditious cartoon “Having Their Fling,” which depicted an editor, a capitalist, a politician, and a minister dancing to a tune conducted by Satan. Hundreds of Wobblies from the Industrial Workers of the World were rounded up and prosecuted under the Espionage Act. One Wobbly on trial explained his opposition to the war by saying “This war is a business man’s war.”

Frum’s article doesn’t mention the Act, much less offer a defense of it, probably because it is patently indefensible. He does write that “eminently liberal writer Adam Hochschild accuses Wilson of culpability for the unjust imprisonment, illegal abuse, and outright murder of trade unionists and anti-war dissenters.” This is an obvious attempt to lessen the charges against Wilson. Rather than Wilson’s record attacking unionists and socialists standing on its own, Frum transforms these facts into something “claimed” by an “eminent liberal” i.e. a partisan source.

Wilson’s campaign against free speech led to several landmark Supreme Court decisions restricting that fundamental right. Socialist Charles Schenck was convicted for distributing leaflets that called conscription “a monstrous deed against humanity in the interests of the financiers of Wall Street.” Schenck’s sentence of six months in prison was upheld in the Supreme Court case Schenck v. United States. It was during deliberation that Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes coined the famous “clear and present danger” exception to the First Amendment. Similar convictions were upheld in the cases Abrams v. United States and Schaefer v. United States.

Frum throws a sop to critics of Wilson by admitting to some of his most egregious flaws. Nevertheless, he blames many of them on the President’s stroke saying “Many of the darkest acts of his administration occurred during this period of feebleness: mass deportations of foreign-born political radicals; passivity in the face of the murderous anti-Black pogroms that flared across America's big cities; a de facto granting of permission to the most repressive and reactionary tendencies in U.S. society.”

Frum gives Wilson’s stroke far too much credit. These dark acts would have been entirely predictable from Wilson’s record. It’s not a stretch to go from arresting socialists and anarchists to deporting those socialists and anarchists not born in the country like Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. On the subject of Wilson’s passivity in the face of the Red Summer atrocities against Blacks, Wilson had an opportunity to intercede in an anti-Black riot in St. Louis in 1917, before his stroke. He didn’t. A famous political cartoon covering the incident shows a Black woman with her children before Wilson.“Mr. President,” she asks, “why not make America safe for democracy?” A fair question.

Black trade unionist A. Phillip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters further criticized Wilson for his hypocrisy for preaching democracy in Europe but allowing a racist autocracy in the South. He wrote “Lynching, Jim Crow, segregation, discrimination in the armed forces and out, disenfranchisement of millions of black souls in the South-- all these things make your cry of making the world safe for democracy a sham, a mockery, a rape on decency, and a travesty on common justice.”[6]

In his conclusion, Frum gives more praise to Wilson saying “He showed the way to the modern world.” This is most true in Democratic Party politics. Wilson pioneered the liberal trick of disclaiming the worst excesses of the other side while all the time accepting them. Wilson stated that he opposed the “dollar diplomacy” of Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, but his own policies were very similar. A critic in the New York Times termed Wilson’s foreign policy “ten cent diplomacy.” In words Wilson differed greatly from Theodore Roosevelt who wrote “If any South American country misbehaves against any European country, let the European country spank it.”[7] In practice, though, there was little difference. A contemporary Nation magazine article reported how under U.S. military occupation, Haitians “who protested or resisted [forced labor] were beaten into submission…those attempting to escape were shot.” During Senate hearings on the military’s conduct in the Dominican Republic it was recounted that “elections were prohibited;…public meetings were not permitted;...destructive bombs were dropped from airplanes upon towns and hamlets;...”[8]

Frum continues “Cancel Wilson, and you empower those who seek to discredit the high goals for which he worked. Those are goals still worth working toward. To realize them, supporters of American global leadership cannot dispense with the practical and moral legacy of Woodrow Wilson.” No one can deny that Wilson was practical. He never let his stated ideals get in the way of what he thought was best for the U.S., which he normally identified as being best for the rich and corporations. Wilson’s moral statements were a front. Those sweet words were often a cover for shameless imperialism. Viewing hypocrisy as morality is a truly strange worldview. Perhaps it’s because he shares that worldview that Frum is qualified to be a writer for the Atlantic.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- William Appleman Williams, The Tragedy of American Diplomacy (Cleveland: World Publishing Company, 1959) 48. ↩

- Woodrow Wilson, The State (Boston: D.C. Heath and Company, 1893), 667. ↩

- Scott Nearing and Joseph Freeman, Dollar Diplomacy: A Study in American Imperialism (New York: Viking Press, 1925), 97. ↩

- Gabriel Kolko, The Triumph of Conservatism: A Reinterpretation of American History, 1900-1916 (New York: Free Press, 1963) 207. ↩

- Ray Ginger, The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene V. Debs (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1947) 333. ↩

- John Nichols, ed., Against the Beast: A Documentary History of American Opposition to Empire (New York: Nation Books, 2004) 194. ↩

- Sidney Lens, The Forging of the American Empire: From Revolution to Vietnam: A History of U.S. Imperialism (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company 1971) 204. ↩

- Nearing and Freeman, 130. ↩