Martin Rose argues that Lenin’s classic political strategy offers an alternative to the economism which plagues both sides of the debate around ‘degrowth.’

Within the ecological left, there are essentially two lines of thought: the eco-modernist line held by Matt Huber, and the “degrowth communist” line held by Kohei Saito. While seemingly opposed, both share a flawed foundation in economism that distracts them from the political struggle necessary for liberation.

Huber correctly argues that the ecological crisis requires “full social control (planning) over the social relation to nature.”1 Huber’s view of such a rationally-planned economy, however, mistakenly concludes that infinite growth is possible on a finite planet, and that this growth is all that is necessary to liberate both people and the planet.

Meanwhile, Saito argues that we should “rehabilitate” Marxism in order to address the ecological crisis.2 Saito’s view of a “rehabilitation” of Marx, however, is paradoxically both revisionist and dogmatic, insisting on a strict faithfulness to a small selection of Marx’s texts while at the same time using cherry-picked evidence and hermeneutic gymnastics to distort not only the thought of Marx, but the role of Marxism as a scientific discipline. The end result utterly defangs the revolutionary potential of Marxism.

The twenty-first century demands extreme analytical rigor. We face extinction. The stakes could not be higher. Yet, the polemic between “degrowth Marxists” and “eco-modernist Marxists” lacks the seriousness necessary for a discussion on how we, as a species, avoid extinction. Huber and Saito, pitted against each other, both argue from flawed presuppositions that condemn us to ecological and political failure. Marxist organizers need a firm, analytical middle ground to inform the political actions necessary to save the earth and its people. Marxism reveals to us that political struggle is the key to liberation from capitalism and the transition to socialism. Achieving harmony with the planet is no different. It will be won through political struggle and cannot be reduced to purely economic processes.

Huber’s Misunderstanding of Ecological Limits

While Huber claims that “the goal of socialism was not the expansion of production itself, but rather the ‘free development’ of human beings,” he consistently equates the two.3 While claiming “flexibility,” Huber consistently contradicts both scientific literature and Marxist theory in service of his inflexible devotion to economic growth.

Huber fails to grasp the ecological dimension of degrowth literature. To take one example, Huber’s critique of planetary boundaries falls apart when one actually reads the experts. The planetary boundaries framework outlines a set of rigorously-determined ecological “limits” for biodiversity, climate change, biogeochemical flows, and more that, when passed, would push the planet out of Holocene conditions and into a geological epoch that social and ecological systems are not equipped to handle. Huber claims that “as soon as the concept of fixed planetary boundaries was proposed, it was hotly debated and critiqued by scientists of various stripes.”4 The “hot debate” he cites is a short paper published in 2009, the year the original paper on planetary boundaries by Rockström et al. was released.5 The paper, in fact, calls the planetary boundaries study “a creditable attempt to quantify the limitations of our existence on Earth,” and even advocates for a more strict placement of the boundaries, noting that

[i]f the history of environmental negotiations has taught us anything, it is that targets are there to be broken. Setting limits that are well within the bounds of linear behaviour might therefore be a wiser, if somewhat less dramatic, approach. That would still give policy-makers a clear indication of the magnitude and direction of change, without risking the possibility that boundaries will be used to justify prolonged degradation of the environment up to the point of no return.6

Many of the other issues raised by the paper, which were valid at the time, were taken into account by the “planetary-boundaries” researchers, who rectified them in the two updated works on planetary boundaries, released in 2015 and 2023.7 Furthermore, the “scientists of various stripes” whom Huber cites are actually one scientist (the paper actually has no author listed) who comments that “the history of human civilization might be characterized as a history of transgressing natural limits and thriving,” a statement whose ignorance bleeds into cruel apathy as one considers the impacts of anthropogenic climate change that the poor and marginalized are disproportionately facing due to climate breakdown.8

Huber argues further that even if the planetary boundaries were legitimate, they would not necessarily imply hard limits to economic activity, citing the example of the stratospheric ozone planetary boundary, which “has basically already been addressed by a simple technological switch initiated by the 1987 Montreal Protocol.”9 The Montreal Protocol called for the global elimination of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), chemicals which slowly destroyed the ozone layer. In order to eliminate CFCs without negatively affecting economic activity, a replacement was found. The replacement, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), are a greenhouse gas much more potent than carbon dioxide. The Montreal Protocol only shifted the destructive impacts of economic activity from the ozone layer to the broader climate.10 The case study of the Montreal Protocol, rather than disproving the idea of ecological limits, is a potent reminder that “simple technological switches” only shift ecological impacts. Economic activity as a whole needs to be scaled down in order to definitively reduce ecological damage.

With the harsh reality of ecological limits in mind, Huber’s claims on the vast amounts of resources needed to address climate change become truly dangerous. Huber fails to take into account the economic impacts and ecological limits of resource extraction involved in the production of renewable energy. Renewable energy, like the switch to HFCs, simply shifts environmental impacts from one planetary boundary to another,11 and even transubstantiates environmental issues into social ones, leading to biodiversity loss and economic imperialism. Both would result in extreme, and potentially irreversible, instability for both ecological and human systems.12

Despite Huber’s claims to the contrary, this level of resource extraction is not necessary. He argues we need massive levels of investment in order to create enough renewable energy to meet society’s needs, but in the paper he cites for this claim, the needs modeled are not human needs, but those of an economy predicated on economic growth! Huber’s evidence for the necessity of a growing economy comes from a paper whose data are not applicable to the question he attempts to answer.

Degrowth exists precisely to avoid the scenario that Huber sees as necessary. And it can be avoided: research suggests that, contrary to Huber’s claim, it is possible to thoroughly meet human needs with much less energy than we currently use (for developed countries, this is measured to be 95% less than current consumption).13 Huber is simply not familiar enough with the ecological-economic literature to be a reliable source regarding the necessity of growth.

Huber’s Misunderstanding of Capitalism

In the face of the literature above, Huber claims:

It is entirely clear that solving climate change requires massive development of the productive forces […] Imagine what it would take to give the entire planet public housing, public transit, reliable electricity, and modern water-sewage services. Now imagine trying to achieve this while also shrinking aggregate material resource use. To say the least, this sounds like a difficult task.14

This quote reveals Huber’s second fatal flaw: his misunderstanding of the nature of capitalist overproduction and accumulation, which is the real cause of society’s high material and energy throughput.15

For example, Wiedemann et al. show ways we can look at this—either in terms of capitalist consumption, or in terms of systemic drivers of economic growth.16 First, capitalist consumption: because income is linked to consumption, great disparities in income lead to great disparities in ecological impact. The wealthy capitalist is able to use their profits for luxury food items, private jets, and high-end cars. These goods make up a significant portion of our ecological overshoot, and they are used exclusively by the ruling class.

There are also systemic drivers of increased throughput: for capital’s sake, workers are forced to work the same or more hours despite increases in labor productivity; workers need to be provided more jobs in order to keep technologically-driven unemployment in check, and to sell all the commodities produced by the growing economy; the prevalence of advertising and planned obsolescence. And this is not even taking into account that there are entire industries that exist solely for the reproduction of the capitalist class. These include arms manufacturing, single use plastics, and fossil fuels. Given that the above drive material and energy throughput while providing little social use, they are also degrowth’s main targets.17 More time can be put into meeting people’s needs with lower aggregate economic activity if society isn’t wasting economic resources and ecological space on luxury goods, needless overproduction, and ecologically- and socially-destructive industries. And this means that your average person will be able to have more of their needs met all while working less. Their material and energy footprints are really neither here nor there when pursuing the main goals of degrowth. The vast majority of material and energy throughput, while it might be connected to the average person’s life in some way, is often not directly attributable to a single person, but rather to the system of capital as a whole, and to the structures that maintain it. To see degrowth as a reduction in the amount of resources dedicated to any given worker’s well-being is to miss the deeper, structural reasons for such high material throughput under capitalism.

But the question of Global North consumption still stands: the current material intensity of living for a significant number of people in the Global North cannot be sustained, and it precludes ecologically-safe development for the Global South. This, however, is not the fault of workers in the North choosing materially-intensive lifestyles, but the fault of the systemic tendency towards overconsumption inherent to capitalism. Therefore, “Degrowth Marxists” see the solution as a holistic view of developing the economy to fit social needs, which can only come to be through a democratically-planned economy.

Ecological planning would, under no circumstances, prevent the provision of people’s basic needs—quite the opposite. Economies of the Global South have a right to develop and grow their economies to the degree that they meet human needs. Given that the Global North is responsible for the majority of ecological breakdown, it follows that degrowth in the North would, as a form of ecological reparations, provide ecological “space” for the development of the Global South.18 Even then, workers across the world would see improvements in well-being due to the reorientation of the economy around their needs: they would get universal basic services, public transport, and shorter work weeks. The poorest don’t stand to suffer from degrowth precisely because society’s high material throughput doesn’t come from the provision for their needs, but from capitalism and its reproduction.

Huber’s Misunderstanding of Socialism

Socialist planning and degrowth are not inherently opposed to each other. The goal of planning is not to develop the productive forces, but to rationally govern the economy. Reducing aggregate economic activity is precisely what a rationally-governed economy would do, given ecological limits and the nature of capitalist overproduction.

A rational economy would be rid of capitalist accumulation, planned obsolescence, perceived obsolescence, and advertising, offering instead longer-lasting, repairable goods, universal basic services, and commonly-held, durable infrastructure. Furthermore, destructive industries like arms manufacturing, single use plastics, and fossil fuels will, of course, be expropriated and decommissioned. These are not radical proposals from a socialist standpoint; if anything, they reveal that decreasing energy and material throughput is precisely what economic planning looks like in developed capitalist economies. Of course, some industries will need to grow, but these few industries will barely hold a candle to the irrationally-high material throughput prompted by anarchic markets under capitalism.

We must not simply wait for Huber’s vision of “development” to resolve the contradiction between us and nature because his view of “development” (economic growth) is precisely the primary contradiction between capital and nature in our current moment. Ecosocialism, in contrast to capitalism, allows us to say: “What is necessary for us to traverse this deep, complex relationship between the people and the planet?” The answer should be clear: Not growth.19 To say otherwise is to engage in analysis that is, at best, not serious and, at worst, dishonest. We can live dignified lives within ecological limits.20 Why is Huber so afraid to admit this? Why is he afraid to even admit the legitimacy of the concept of ecological limits if it poses no serious threat to human flourishing?

Huber complains that the assertion of ecological limits is “eco-austerity” that prevents socialism from “unleash[ing] human potential from the shackles of capitalism and its market imperatives.”21 Huber uses the word “austerity” as if it is congruous with less material use—and no other statement could be as weighed down by the “shackles of capitalism” as this.22 Material throughput is not, and has never been, an adequate measure of human well-being; the implementation of social provisioning systems is actually a much better proxy.23 Huber’s material fetishism implies that even once human needs are met by socialized provisioning systems, “human potential” must necessarily be met by more material and energy use.

But there is something more conducive to human potential: leisure. Work-time reduction, job-sharing, and a job guarantee provide beautiful opportunities to discover our human potential through the arts, social bonds, and simple rest or exercise. Why insist that flourishing must be material-intensive? We do not need more material goods to flourish. Ecosocialist degrowth isn’t austerity, it’s free time.

What is Huber trying to defend when advocating against degrowth? Is it cheap, non-durable appliances? Is it the sea of disposable plastics we have produced? Is it deforestation, mining, and the subsequent destruction of ecosystems? He would, of course, say otherwise, but this is what his vision implies. Our economy, as it stands, has an absurdly high material and energy throughput. To continue growing this throughput, the maintenance of planned obsolescence, single use plastics, fossil fuels, and arms manufacturing would necessarily have to continue. Houses would have to be made poorly. Our transportation infrastructure would continue to be utterly inefficient. Huber would never explicitly advocate for these things and, of course, he doesn’t. When he polemicizes against degrowth, he advocates for the building of more to meet people’s needs. Of course, this is necessary. Once built under socialist planning, these infrastructure installments would be made more durable and useful than under capitalism due to the absence of the profit motive. In this case, the horizon of these projects is degrowth—an economy where most projects are done, and most economic activity would consist in occasional repairs to this infrastructure. This would be a steady-state economy with less energy and material throughput than before. To do anything else would be irrational, given ecological limits.

Huber’s Misunderstanding of Marxism

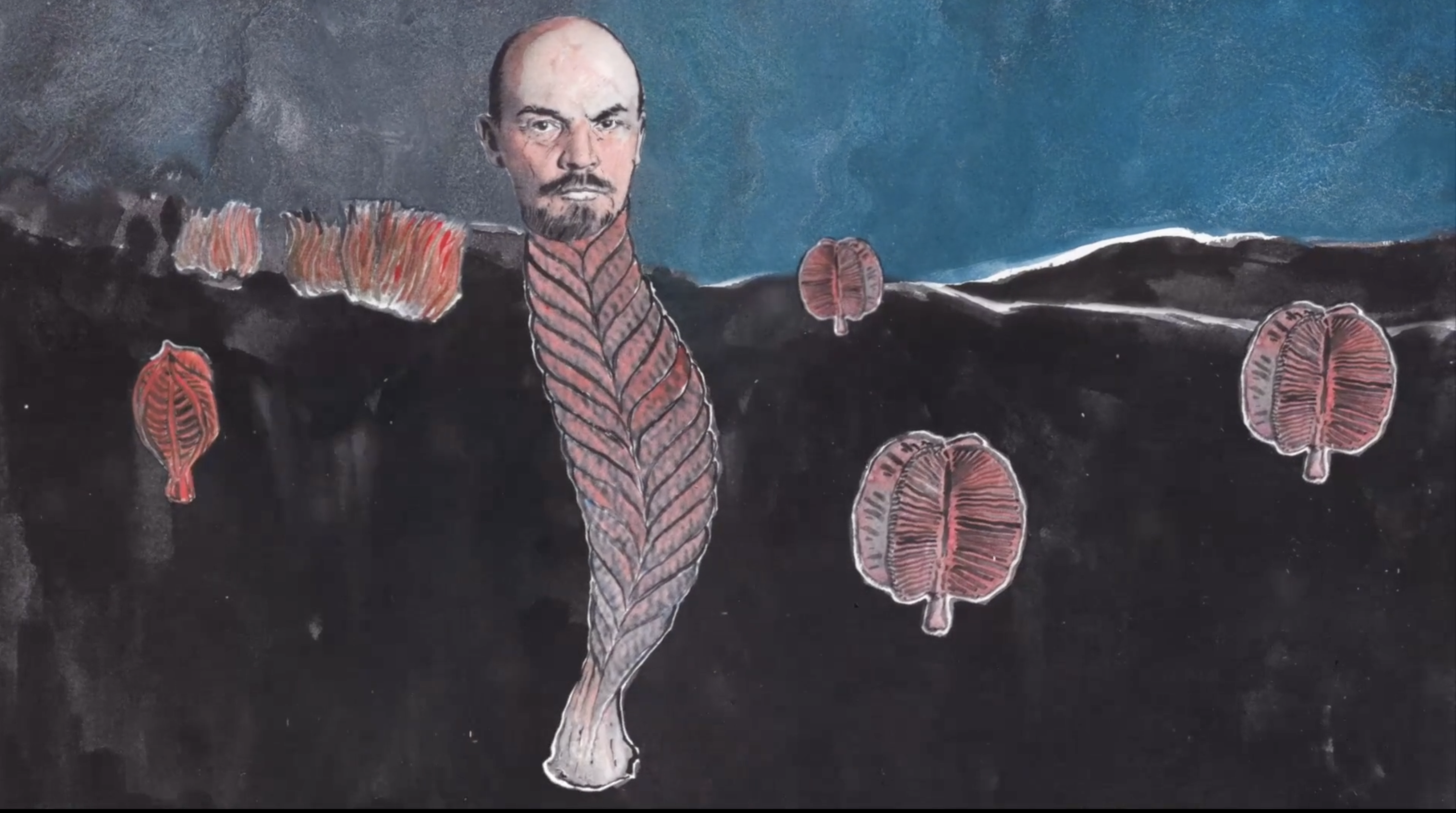

Marxists should be familiar with the fallacy underlying Huber’s analysis. Even old Lenin, ignorant of the existential threat we face today, could have critiqued Huber. This is because Huber’s analysis rests on the idea that the “development of the productive forces, not the class struggle, is the driving force in history.”24 This is called economism. Huber’s ecological economism posits that the key to ecosocialism is further “development,” rather than political struggle against the capitalist mode of production. Huber seems to understand the importance of class struggle to ecosocialism (as seen in his Climate Change as Class War), but his view of class struggle is one in which all class struggle is fought and won in one short outburst. But class struggle is the moving force of history, taking us from capitalism to socialism, and from socialism to communism. If it is class struggle, not the development of productive forces, that liberates people, then it is also class struggle, not the development of productive forces, that liberates the planet. The key to ecosocialism is not economic, but political.

But before we can outline an alternative to Huber’s view of development, it is necessary to critique one of Huber’s opponents, “degrowth Communist” Kohei Saito. Only after exposing Saito’s weak points can we repeat his critique of the “productivist” Marxism that Huber touts while maintaining Marxism’s commitment to organized, political struggle.

Saito’s Misunderstanding of Marxism

While Saito tends to read between the lines so much he forgets what is on the lines themselves, his efforts to apply the insights of Marxism to our current ecological juncture are commendable. However, his approach does not hold up to scrutiny. Not a Marxist but a Marxologist, he engages not with a school of thought but with a series of sacred texts whose interpretation is to be left to the priests of the Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (MEGA).25 It is necessary, however, to wrest these texts from the hands of Saito in order to promote an engagement with both the works of Marx and the tradition of Marxism.

Shrinking society’s material throughput and disregarding GDP as an adequate measure of progress is necessary. Marxism is how we achieve this. But Saito’s reading of Marx does not synthesize these two in a productive way. In fact, his insights as to how we are to reach communism are inaccurate according to Marx himself, and we don’t even have to read between the lines for it!

In his book, Slow Down, Saito argues that the Marxism of old is done for: we must return to Marx and find where Marx’s late thought diverged from 20th century productivist, Eurocentric Marxism. Saito’s main claim regarding political praxis is that Marx would have forgone “transforming the political system” and instead advocated for communism, or “voluntary mutual aid between workers.”26 Communism would be (immediately) achieved when people “[reclaimed] the commons” by starting cooperatives and municipalizing energy.27 He cites Marx to support his claim:

Marx himself praised the efforts of workers’ co-ops, “acknowledg[ing] the co-operative movement as one of the transforming forces of the present society based upon class antagonism.” He goes on to assert that the workers’ cooperative movement shows how it was possible to replace the current capitalist system founded on scarcity with “the republican and beneficent system of the association of free and equal producers, even calling the workers’ co-op an example of ‘possible communism.’28

Saito’s reading is categorically false. If Saito had even read the rest of his source, he would have known that. Marx says, right after Saito’s mutilated quote,

“Restricted, however, to the dwarfish forms into which individual wage slaves can elaborate it by their private efforts, the co-operative system will never transform capitalist society”; rather, to achieve socialism, or “one large and harmonious system of free and co-operative labour, general social changes are wanted, changes of the general conditions of society, never to be realised save by the transfer of the organised forces of society, viz., the state power, from capitalists and landlords to the producers themselves.”29

Saito evacuates Marx of all his political content and in doing so, reveals that he knows little about Marxism. Statements similar to the one above are replete in the works of Marx and Engels, who, through all their work (and this isn’t between the lines but painfully explicit) insist on the path to socialism being through a political war waged against the state.

The form of this political struggle is made explicit as well. Engels expresses it best in his “Reply to the Honourable Giovanni Bovio”:

Marx and I, for forty years, repeated ad nauseam that for us the democratic republic is the only political form in which the struggle between the working class and the capitalist class can first be universalised and then culminate in the decisive victory of the proletariat.30

Perhaps forty years wasn’t enough!31

In short, Marx would not advocate for a path to communism via reclaiming the commons as Saito claims. Marx believed, instead, that communism can only be achieved if socialists first smash bourgeois state power by creating a democratic republic— only then can class struggle progress through socialism to communism.

Saito’s ecological insights, we can critically keep. However, the way he reaches them—Marxology, or the borderline-theological insistence on the primacy of the texts of Marx and nobody else (not even Engels!)— must be critiqued. It is okay if Marx did not answer the question of economic growth. However, if we are Marxists, then we understand that the methods and categories that he provided us with are invaluable. A functional synthesis of degrowth and socialism is possible if one engages with the thought of those that follow Marx’s tradition of scientific socialism. We must not read into something that is not there but, rather, critique the tradition which sidelined the questions of ecology and economic growth using the tradition’s own categories. Below is a critique of productivism rooted in Marxism and its development which I will call Eco-Leninism. Eco-Leninism is a necessary corrective to both Saito’s political incompetence and Huber’s ahistorical, dogmatic insistence on economic growth.

Eco-Leninism

Insights from the history of socialism and the living science of Marxism can be applied to our current historical moment.32 We can begin with one of Marx’s greatest successors, Lenin. As noted earlier, Lenin was a staunch opponent of economism (the belief that the “development of the productive forces, not the class struggle, is the driving force in history”).33 Lenin fought economism both before and after the Russian Revolution. Before the Revolution, fighting economism meant centering political struggle in the battle against the autocratic state and for democracy, or the dictatorship of the proletariat (not at all different from the line we should take against Saito!). After the Revolution, however, this same conflict appeared in debates over economic development. The Bolsheviks then faced the important but as of yet only cursorily considered question: What does socialist economic development look like? How does the working class slowly begin its historical mission to create a stateless, classless society? There were two main players in this debate: the right, who advocated for the New Economic Policy (NEP), and the left, who advocated for rapid industrialization through “socialist primitive accumulation.”34

Under the NEP, in place from 1921 to 1926, the Soviet government held control over banking, foreign trade, and large-scale industry while allowing for the rest of the economy to operate under restricted market principles.35 Lenin, continuing to emphasize the role of politics as essential to class struggle and the transition to communism, advocated for the NEP, as it allowed the party and workers to build the necessary relationship with the peasantry through “ideological and cultural struggle, the dissemination of Marxism-Leninism, and the spread of the party in the countryside.”36 The goal was to build trust and slowly win over the masses to socialism and collective work.

In contrast to the NEP, the left wanted to skip over what Lenin (and his ideological successor, Bukharin) saw as necessary—political struggle and “winning people over”—and go right into rapid industrialization, socialist consciousness of the people be damned (not at all different from the line held by Huber!). This would be achieved through the aforementioned “primitive socialist accumulation,” a reference to the violent movement of enclosure that marked the beginning of capitalist accumulation. Primitive socialist accumulation would force the peasants to work in cooperative farms, hoping that socialist consciousness would follow from the modern technology used and cooperative labor practiced in the farms. The left, driven by reasonable fears of the return of capitalism and the loss of the Revolution, won out. Stalin pushed this policy, leading to incredible feats of rapid industrialization but not without considerable and unforgivable human cost.

Paul Costello notes that Stalin’s flaw lies in the “idea that the heart of the class struggle in the USSR was the struggle to lay a material basis for socialism, rather than a campaign for new relations of production, new political and new ideological relations.”37 If we can learn anything from the mistakes of Stalin’s economic policy, it is that development towards communism is not quantitative material development, but qualitative political development. History does not follow the progression of technology, but the politically-determined interests of the ruling class—or, “[t]he history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” This holds socially and ecologically.38 What the NEP model of socialist development offers is development that does not require growth or an increase in material throughput to progress, but rather a political struggle: a struggle rooted in raising the consciousness of the masses, of winning them over to collective, socialized work; of winning them over to leisure, social bonds, art, and the simple joy that can come from an ecologically-friendly lifestyle if only we let it.

Economism plagues the thought of both Huber and Saito. Only by faithfully repeating Lenin’s critique of economism from the time of the Russian Revolution can we, in the lead-up to the Ecological Revolution, create a viable alternative to two dead end strategies.

Economism constrains Saito’s theory of change, denying all political action in favor of “direct” economic action in the formation of cooperatives. This theory of change ignores how the state blocks our path to liberation. In pushing this, Saito repeats the failures of socialists whose ignorance of political struggle kept the movement in limbo.

Economism blinds Huber to the importance of class struggle and ideological war in the transition to eco-socialism, insisting that technology, rather than consciousness, needs to be changed. This model of economic development ignores the vital role of class struggle in the development of socialism even after the dictatorship of the proletariat has been achieved. In doing this, Huber repeats the failures of Stalinist economic policy.

Conclusion: Outlines of an Eco-Leninist Program

“Eco-Leninism” is not a call for austerity but for liberation from the cycle of endless growth that threatens to haunt us even after the dictatorship of the proletariat is reached. If we do not actively struggle against ecological economism, eco-modernism, and techno-optimism here and now, then our planet will be irreversibly damaged. The class struggle continues even after the revolution. Once the overconsumption of the most wealthy has been taken care of, once infrastructure for people’s needs has been taken care of, the remnants of the market will become the final frontier of struggle in which we win the people over to a system of collective living in harmony with the planet. We must fight against ecological economism and mindless productivism, and advocate for an alternative in which wasteful capitalist industries are expropriated and decommissioned, through which we promise to meet the basic needs of the people while encouraging more leisure, art, and social bonds.

Living in harmony with the planet means degrowth. We must, then, make this a part of our vision of communism. But, in order to achieve this, we must partake in political struggle.

In the arena of politics our goal should be as follows:

We must achieve the democratic republic, the dictatorship of the proletariat. This means that we require a true democracy in which people have universal and equal suffrage which they use to elect accountable representatives to a single legislative body. This legislative body will be subordinate to the people in all circumstances.

We must ensure protections for workers and restrictions on private ownership, which allow for full, democratic participation by all people. This means a mandatory living wage, mandatory worker safety laws, lower working hours, universal basic services, state ownership of enterprises past a certain size, and national holidays on election days.

We must struggle politically for rational economic planning. Planning would set a resource-extraction limit and regulations on the nature of resource-extraction for state-owned industries. Industries must produce the highest-quality products possible, erasing practices of planned and perceived obsolescence. The state must expropriate industries that are exceptionally, ecologically- and socially-harmful, and decommission them. The state must expropriate the renewable energy industry to begin the global transition to clean energy. Clean energy will be scaled up within ecological limits, giving the world the amount of energy needed to live within planetary boundaries.

We must struggle politically for social job guarantees and job-sharing to ensure that working people need not worry about losing their living once destructive industries are decommissioned.

We must then engage in a political struggle against the remnants of the market. Through this struggle, the market would be overcome by collective, democratic economic planning and cooperative labor. Those who participate in the economic plan must then be won to the view that less is more, or that aggregate economic activity should be scaled down. This program consists in a simple dynamic: society is given to democratic control, and through this avenue for democratic deliberation, the struggle for ecosocialism is waged. We cannot delude ourselves into thinking that the model for economic development of 20th-century socialism must carry into the 21st century. As Marxists, we must engage in thorough and rigorous analysis of the material conditions in which we find ourselves. Armed with the knowledge gained from this analysis, we can then reach for a future for humanity that is free from all forms of domination.

- Matt Huber, “The Problem With Degrowth,” Jacobin, June 16, 2023, https://jacobin.com/2023/07/degrowth-climate-change-economic-planning-production-austerity.

- Kohei Saito, Slow Down: How Degrowth Communism Can Save the Earth, (New York: Astra House 2024).

- Matt Huber, “The Problem with Degrowth.”

- Matt Huber, “The Problem with Degrowth.”

- Rockström, Johan, Will Steffen, Kevin Noone, Åsa Persson, F. Stuart Chapin III, Eric Lambin, Timothy M. Lenton et al., “Planetary boundaries: exploring the safe operating space for humanity,” Ecology and society 14, no. 2 (2009).

- “Earth’s boundaries,” Nature 461, no. 7263 (September 2009): 447-448.

- Will Steffen, Katherine Richardson, Johan Rockström, Sarah E. Cornell, Ingo Fetzer, Elena M. Bennett, Reinette Biggs et al. “Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet,” Science 347, no. 6223 (January 2015): 1259855. Richardson, Katherine, Will Steffen, Wolfgang Lucht, Jørgen Bendtsen, Sarah E. Cornell, Jonathan F. Donges, Markus Drüke et al. “Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries,” Science advances 9, no. 37 (September 2023): eadh2458.

- “The Planet of No Return,” The Breakthrough Institute, January 6, 2012, https://thebreakthrough.org/journal/issue-2/the-planet-of-no-return. Joern Birkmann et al. “Chapter 8: Poverty, Livelihoods, and Sustainable Development,” Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, February 22, 2022, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-ii/.

- Matt Huber, “The Problem with Degrowth.”

- And the proposed alternative to HFCs, HFOs, releases TFA, an acid, into drinking water. See the following article for information on the Montreal Protocol and the environmental impacts of the various chemicals. Michael Kauffield, and Mihaela Dudita, “Environmental Impact of HFO Refrigerants & Alternatives for the Future,” Open Access Government, June 11, 2021. https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/hfo-refrigerants/112698/https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/hfo-refrigerants/112698/.

- It should be noted that the effects of renewable energy production (land use change and biodiversity loss), can also contribute to climate change, albeit not as directly as greenhouse gasses.

- Jason Hickel, “The limits of clean energy,” Foreign Policy 6, September 6, 2019. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/09/06/the-path-to-clean-energy-will-be-very-dirty-climate-change-renewables/

- Joel Millward-Hopkins, Julia K. Steinberger, Narasimha D. Rao, and Yannick Oswald, “Providing decent living with minimum energy: A global scenario,” Global Environmental Change 65 (September 2020): 102168.

- Huber, “The Problem with Degrowth.”

- Material and energy throughput, also known as social metabolism, is a measure of “the entire flow of materials and energy that are required to sustain all human economic activities.” Helmut Haberl, Marina Fischer‐Kowalski, Fridolin Krausmann, Joan Martinez‐Alier, and Verena Winiwarter, “A socio‐metabolic transition towards sustainability? Challenges for another Great Transformation,” Sustainable development 19, no. 1 (2011): 1-14.

- Thomas Wiedemann, Manfred Lenzen, Lorenz T. Keyßer, and Julia K. Steinberger, “Scientists’ warning on affluence,” Nature Communications 11, no. 1 (June 2020): 3107.

- Jason Hickel. “What does degrowth mean? A few points of clarification,” Globalizations 18, no. 7 (September 2020): 1105-1111.

- Jason Hickel. “What does degrowth mean?” Jason Hickel, Daniel W. O’Neill, Andrew L. Fanning, and Huzaifa Zoomkawala, “National responsibility for ecological breakdown: a fair-shares assessment of resource use, 1970–2017,” The Lancet Planetary Health 6, no. 4 (April 2022): e342-e349.

- Again, let it be clear that by this I mean aggregate economic growth. There are sectors that can stand to grow, but aggregate economic activity, mostly attributable to capital and its reproduction, can not stay as it is if we want to maintain a liveable planet.

- Hauke Schlesier, Malte Schäfer, and Harald Desing, “Measuring the Doughnut: A good life for all is possible within planetary boundaries,” Journal of Cleaner Production (2024): 141447.

- Huber, “The Problem with Degrowth.”

- Ibid.

- Dylan Sullivan & Jason Hickel, “Capitalism and extreme poverty: A global analysis of real wages, human height, and mortality since the long 16th century,” World development (2023): 161, 106026.

- Paul Costello, “On the Stalin Question,” Cosmonaut, July 1, 2021, https://cosmonautmag.com/2021/06/on-the-stalin-question/.

- In English, the Marx/Engels Collected Works, the definitive collection of published, unpublished, and personal writings from Marx and Engels.

- Saito Slow Down, 182, 90.

- Saito Slow Down, 160.

- Saito Slow Down, 163.

- Karl Marx, “Instructions for the Delegates of the Provisional General Council,” Der Vorbote, Nos. 10 and 11, October and November 1866 and The International Courier, Nos. 6/7, February 20, and Nos. 8/10, March 13, 1867. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1866/08/instructions.htm

- Friederich Engels, “Reply to the Honourable Giovanni Bovio,” Critica Sociale, No. 4 (February 1892) https://marxists.architexturez.net/archive/marx/works/1892/02/critica-sociale.htm

- Further exploration of Marx and Marxism’s deep ties to political struggle for a democratic republic can be found in Luke Pickrell’s “Marxism and the Democratic Republic.” Luke Pickrell, “Marxism and the Democratic Republic,” Cosmonaut, May 25, 2023 https://cosmonautmag.com/2023/05/marxism-and-the-democratic-republic/.

- For this section, much of the history is from Paul Costello’s “On the Stalin Question” and Alec Nove’s An Economic History of the USSR.

- Costello, “On the Stalin Question.”

- Ibid.

- Alec Nove, An economic history of the USSR. (Harmondsworth: Penguin Press, 1969) 80.

- Costello “On the Stalin Question.”

- Ibid.

- For an ecological example, Andreas Malm, in his seminal work Fossil Capital, fights against the Stalinist, mechanical materialist conception of history. He reveals that the introduction of fossil fuels into the world economy was not because of their inherent efficiency and technical superiority over other forms of energy, but the benefits they bestowed to the capitalist class in their fight against the working class. Andreas Malm Fossil capital: The rise of steam power and the roots of global warming, (London: Verso Books, 2016).