Kaveh Dadkhah and Rob Ashlar introduce Dadkhah’s translation of Farangis Bakhtiari’s analysis of the 2019 Uprising of Aban.

Preface

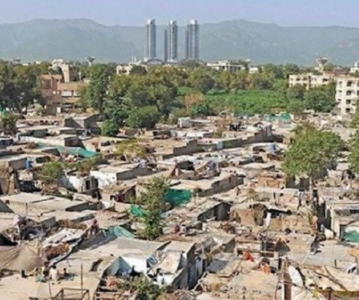

Despite frequent discussion, Iran remains a blank spot for most western-based Marxists. This is unusual for a country of its size, history, and influence. Its system of government, the Islamic Republic (IR), and its political economy remain shrouded in mystery. On the left, some have attempted to fill this void and have put forth a position about the country. Many socialists (particularly of the Marxist-Leninist variety) insist that the IR is a leading force in the struggle against western imperialism and that it sincerely represents the Iranian people, contra pro-western monarchism. Some even suggest that Iran’s economy is social-democratic, i.e., that there exists a kind of welfare state which protects ordinary Iranians. For these reasons, it is argued that we communists must ‘critically support’ the Iranian state against the west. All of this is an opportunist lie. The IR’s saber-rattling with the west is a recent development, confined to the past decade or so. Prior to that, it was fully willing to participate in western interventionism, particularly in Afghanistan (backing the northern alliance) and in Iraq (backing various Shia Islamist militias, such as Muqtada al-Sadr’s). It is strange that an ‘anti-imperialist’ state would partake in such nakedly imperialist ventures, in collaboration with such arch-imperialists as the US and UK. Similarly, the IR is a fiercely neoliberal state, more extreme than even post-1973 Chile and rivaled only by post-1966 Indonesia, that subjects its workers to horrific abuses. For instance, upwards of 10 million Iranians labor in underground workshops, in which they have no protections, insurance, etc. They may die or be killed with no consequences. Millions more live in barbaric slums on the outer rings of cities. Ethnic minorities suffer even worse conditions, alongside racial oppression–many well-off Persians would happily exterminate Iran’s Kurds, Baluchis, and Hazaras. During the Uprising of Aban (November) 2019, which this essay analyzes, the IR murdered roughly 3000 people. Some even estimate up to 8000 dead. Such is the IR’s ‘benevolent’ rule.

Iranian neoliberalism dates to 1980, when the IR first took power, an event mired in myth and legend. To begin, capitalism was established by the Pahlavi monarchy, which sought to turn Iran into a westernized industrial society. Persian ethnonationalism was law, and ordinary people of all ethnicities were terribly exploited (indeed, the IR took its first lessons from the Shah). Then, in 1979, the Iranian masses heroically stood up to end their miserable oppression, leading to a popular insurgency in the north of the country and an impressive workers’ council movement that swept the nation. In the north and in greater Tehran, factory councils, akin to soviets, emerged. In the south, the communist oil workers’ union seized fields, refineries, etc., and brought the national economy to a halt. Turkmen in the east and Kurds in the west seized the land and established village councils. The nation was undergoing workers’ and peasants’ revolt. It may well have become an Iranian proletarian republic–but the revolting masses were not the only ones with plans. On the left, the USSR deliberately obstructed Iranian communists from seizing power because they opposed Soviet leadership and criticized Soviet conduct with the eastern bloc. More immediately pressing, far-right forces, which had long-collaborated with the Shah but saw the writing on the wall, were waiting in the wings. They entered the political stage with other ideas. Meanwhile, the Iranian left was experiencing some cracks. All supported the insurgency and the councils, but none were quite ready for the movement headed by an old cleric, recently arrived from France. It is this movement that would displace the radical left, large sections of which (like the pro-Soviet Tudeh) under the foolish illusion that the ‘Islamic Revolution’ represented a progressive force. In other words, as in Indonesia, many left-wingers in Iran went straight to the people who would slaughter them. Thus, that which had been pioneered by the elder Shah and matured by the younger Shah was now perfected by a man who was later called Ayatollah. It is this man who would turn Iran into the dystopian neoliberal society it is today.

Indeed, Ruhollah Khomeini is merely the Farsi name of General Suharto and Augusto Pinochet–that is to say, he (and the regime which he helped found) is an avatar of neoliberalism in the third world. Much like his contemporaries, Khomeini’s first order of business was to abduct, torture, and murder countless communists, socialists, radical liberals, trade unionists, and anyone else (many of whose names were supplied by the US and UK) who would oppose his nightmare vision for Iranian society. We are in possession of documents that list literally tens of thousands–an entire generation–of Iranian radicals who were annihilated by the IR. The next order was to apply ‘shock therapy’ to Iran, brutally assaulting the Iranian proletariat and atomizing it into ‘neoliberal subjects’. This violently disrupted Iranian working-class life. For instance, under the Shah, 90% of Iranian workers labored under full-time contracts. Now, 90% work under temporary (often part-time) contracts, ranging from day-labor to yearly at most. Lastly, the fusion of Shia Islamism and Persian (ethno)fascism was completed: today, these ultra-rightist ideologies serve as complementary forces, acting as two sides of the same coin. They are embodied by the IRGC (once commanded by the child-murdering general Soleimani), whose function is revealed by an incident during Aban. In Mahshahr (a predominantly Arab city), hundreds fled army tanks into nearby sugar fields, to which the IRGC promptly set fire, burning alive almost 300 people. It is said that the city stunk of scorched flesh for days. Thus, the IR was born and raised.

Khomeini and his ilk worked very hard to cleanse Iran of the communist contagion. For a time, they succeeded, and a vision other than the IR’s was unthinkable. However, the events of Aban 2019 have shown that their society is now living on borrowed time. Therefore, we publish the first of a several part essay dedicated to the so-called November Man who rose up, and like Dmitri Karamazov, proclaimed

…I could stand anything, any suffering, only to be able to say and to repeat to myself every moment, ‘I exist.’ In thousands of agonies – I exist. I’m tormented on the rack – but I exist! Though I sit alone in a pillar – I exist! I see the sun, and if I don’t see the sun, I know it’s there. And there’s a whole life in that, in knowing that the sun is there.

The Iranian proletariat has many more mistakes to suffer, more brutal lessons to learn, and more progress to make, but this much is true: they exist, they have entered the stage of History, and they will inherit Iran’s future. No amount of repression will change that.

––Rob Ashlar

The events of Aban ’98 [‘19] were traumatic for our nation. Once again, the wolves of the bourgeoisie were let loose on many of our people, slaughtering them wholesale for the crime of seeking freedom, dignity, and justice. This, unfortunately, has occurred many times in the history of our country – but Aban marks a turning point. Never has the Iranian working class taken such a lead in the destiny of our nation since the short-lived workers’ revolution of 1979, which was put down by the same forces of reaction against which the Aban Human revolted. It has started a wave of uprisings in the following years and the Islamic Republic has had to accept that it no longer has any shred of legitimacy in the eyes of the Iranian working class–if it had any to begin with. This has led to full on war against the populace of our country. The IR has let go of any pretense of reform, suppressing any subsequent legitimate uprisings by the masses, and putting in charge a president infamously known by the people as ‘the butcher’ due to his leading role in the execution of tens of thousands of communists after the Islamic counter-revolution of 1980. My aim with the translation of these articles is to familiarize the Western left with the reality of the situation. Many in the international left believe the Islamic Republic to be an anti-imperialist force and this has created a rift between the Iranian left and the rest of the world’s revolutionary movements. I hope these articles (remaining parts to be completed) can serve as a starting point for the reader’s re-examination of that belief, and hopefully bring about much-needed solidarity with those of us fighting both a fascist regime and global imperialism.

–– Kaveh Dadkhah

Part One

“Yet the traditional left seemed blind to this situation [of the Indigenous] and occupied itself only with workers in large-scale [heavy -KD] industry, paying no attention to their ethnic identity. Though certainly important for work in the mines, they were [historically – KD] a minority in comparison with Indigenous workers, who were discriminated against and even more harshly exploited. … The problem for the traditional left is that it confused the concept of “the proletarian condition” with a specific historical form of wage labor. The former has spread everywhere and become a worldwide material condition. It is not true that the world of labor is disappearing – there have never been as many workers in the world, in every country. But this huge growth of the global workforce has happened at a time when all the existing trade union and political structures have been breaking up. More than at any time since the early nineteenth century, the working-class condition is once again a condition of and for capital. But now in such a way that the world of workers has become more complex, hybridized, nomadic and de-territorialized. Paradoxically, in an age when every aspect of human life has been commodified, everything seems to happen as if there were no longer any workers.” (Álvaro García Linera, “The Indigenous Worker and the Revival of the Left“)

This text does not intend to dissect the great and groundbreaking upheaval of Aban (November). The videos, the mourning cries of mothers and fathers, the number of those killed, wounded, and the imprisonment of thousands of youth, which reminds every witness of the massacres of the dark ages, the image of the poor who have broken the chains of Kukh Neshinan ideology1, entered the streets and been gunned down from every direction – these already achieve that.

This text does not intend to justify and interpret the aggression of the protests. The burning of banks, centers of oppression, riot police vehicles, and centers of corruption filled with plunderers of people’s wealth in the guise of seminaries, done by those who can tolerate no longer; in short the explosion of people’s anger at profiteering capital, ideological institutions, and organs of repression, is a legitimate defense against a ruthless regime that is armed to the teeth. Reproduction of violence by the oppressors in intensifying fire and destruction is the perpetual but now useless policy of dictators for absolving themselves in the same old play of “Saboteurs and Vagabonds”. The same words are echoed from Reza Shah to Mohammad Reza Shah to the current authorities in Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon; It is no more than a repetitive story that gets no response but the people’s ridicule.

In the first two parts, this text intends to unveil the lived experience of constant class struggle through the unique perspective of workers who have been driven to the margins of work and life while delving into their consciousness in these battles. In doing so, it considers the staggering statistics of margin/slum dwellers as well as the unemployed and unstable workers – those who make up the largest part of the labor force on the class struggle front. In the third and final part, through a framework extrapolated from the text, it intends to engage in a brief deconstruction of the Aban uprising – the role of the practice of the self-perpetuating subject of Aban [the so-called Aban Human – KD].

Introduction

In the fall of 1398 (2019), while the dictatorship was busy imprisoning, prosecuting, and torturing students, militant intellectuals, and representatives of workers in large factories, in basements in the margins of urban spaces and on the streets – the unstable workers of the cities, the “blind mice of history”, were active. When the explosion of social and political conflicts opens the way for the emergence of the masses as creators of history, the marginalized become the clear symbol of this explosion. Those who, before Aban 1396 (November 2017), had not entered class struggle on a national scale against the dominant power independently, and who, in the struggles of the last half-century, appeared as mere passive followers of one leader or another, this time entered the streets neither within temporal nor spatial boundaries predetermined by charismatic heroes nor within the role determined by them. They did not act as passive followers of Khomeini, Khatami, Mousavi, or Karroubi. They gave up all hope in these characters, washed their hands of optimistic anticipation for national or foreign saviors. In the height of hopelessness and despair, they realized with their flesh and blood that no one would help them but themselves. The increase in price of gasoline, which consumed at least a quarter of their income in the gas tanks of Prides2 and motorcycles, thereby provided a vital part of their income, was a public spark for igniting their anger and filling the streets – a powerful flood burst forward, shattering the apparatus of power and terror.

The people’s solidarity coming from their shared anger during the last week of Aban 1398 (November 2019) marked a significant period in the history of class struggle in Iran. Days in which the destitute, whose voices had been unheard, unseen in the field of class struggle, now regained their pride and self-esteem. Those who were usually overshadowed by strikes and classic protests of workers; the paupers who do not carry the name of a factory or an institution with them – they are known as margin dwellers, paupers, the underprivileged, the poor and Mostaz’afan3. These paupers include all workers – productive and unproductive – who have nothing to sell but their labor power, and although this definition includes the history makers of Aban, it does not show their distinct characteristics. Words like “the poor” and “Mostaz’afan” carry ideological baggage; in addition, they are too general and therefore do not make good descriptors. I prefer to specify the insurgents of Aban [as being] amongst the poor, and I think the term “marginalized”, which includes “margin dwellers” and “marginal workers”, would be a better descriptor than just margin dweller. This is because not only have they been driven outside the urban order and boundaries, but also outside the official conditions of labor. Those marginalized in labor and housing in the past forty years have usually engaged in constant struggle against the dominant order; usually quietly and rarely openly. They have fought patiently and continuously for their survival in their living spaces and on the streets against ever-expanding and ruthless economic austerity. They have matured and hardened, and, during Dey of 1396 (December 2017/February 2018), emerged and revealed themselves in force, and during Aban, entered the scene of class struggle. This text intends to reveal that this was not a spontaneous uprising, but an uprising developed from under the skin of horrific economic, political, and religious exploitation that was once restrained by ideologies born of the ruling religious ideology but had now shed those restraints. The Aban Human sounded the trumpet of the regime’s fall in the streets by freeing himself from the shackles of the ideology that chained him, that of Mostaz’afan. The deconstruction of this being, of his life and labor, is seeing the reality of an invisible movement that stunned everyone in the post-Aban era with its footage. The hegemons claimed that the Human of Aban would bring about another “World War”! but he has been engaged in a war since his birth – not world war but class war. It is a struggle that frightened the representatives of the global hegemony in the Middle East, in addition to the representatives of the religious hegemony of Capital in Iran. The assassination of the child-murdering general [Qasem Soleimani –KD] and their [American –KD] genocidal rockets are mere reactions to the presence of the Aban Human on the streets.

Greetings and respect to the Human of Aban.

***

Since the dawn of capitalist relations and based on the conditions of labor supply and demand, societies have faced migration of workers to sell the only thing which they owned. In the twentieth century, the internal structure of underdeveloped countries was integrated into the world order. Therefore, local production was limited to a few specific products which fit this division of labor. The structures of traditional economy and the agricultural sector were taken over and reshaped by the manufacturing industry and unproductive labor [service labor -KD], forcing the surplus of the rural labor force to migrate to big cities, thus transforming rural unemployment into urban unemployment. Since 1332 (1953/4), with the use of oil revenues, infrastructure projects have facilitated the movement of commodity capital (that is, imports) and the construction of ideological institutions of capital. These have caused the dismantling of traditional agriculture and solidified capitalist relations in cities. During the 1340s (1960s), and especially after the land reforms and the end of the “Golden Age”, villagers were forced to leave their homes and settle in slums where they were given the proud label of margin (or slum) dweller. With further urbanization, cities have faced a structural problem called “slum dwelling,” and rural poverty has shifted to urban poverty. After the Bahman Uprising (1979), the closure of factories, the beginning of sanctions, the tornado of neoliberalism headed towards Iran, and the slowdown in accumulation of capital have forced workers into insecure conditions (with unstable employment, a competitive job market, and removal of legal labor protections). Thus, the material and social conditions of “selling labor under any circumstances” became so common that the labor force entered commodity relations on a much wider and more individual basis. The neoliberal struggle against the falling rate of profit was reflected in the dismantling of workers’ organizations (absolute prohibition of independent organizations, even for collective bargaining); in the destabilization of labor relations (temporary and day-to-day), the increase in the rate of exploitation (reducing the purchasing power and increasing absolute poverty of workers; excluding the majority of the workers from the Labor Law, decreasing wages and benefits), the black market of goods, and finally in the continuous flood of immigrants further increasing surplus labor (official and hidden unemployment) in cities – this natural course of the ever-expanding conflict between labor and capital has forcibly stationed the vast majority of this surplus army on the outskirts of big cities, looking for bread in the streets and alleys. Thus, increasing exploitation, and total and hidden unemployment [hidden unemployment refers to the state of those who are technically employed but this employment is uncertain in the long run and/or cannot provide for their basic necessities -KD] were the result of the capitalist crisis, especially in the second half of the twentieth century. The marginalized were none other than the unemployed, the unstably employed, and the workers whose work was less value-producing and more service-oriented – all with interactions and mode of conduct different from those of classical workers. They are, as Linera puts it, “a mixture of different professions, intersecting and flexible subjects, fluid and changeable.”

Definition and statistics of margin dwelling and marginal labor in Iran

The phenomenon of marginalization is more prevalent in developing countries, but it also exists in developed countries with its own unique characteristics. These patterns are spatially different from those in the Third World and occur as a phenomenon called the “ghetto”. Ghettos are usually made up of religious, ethnic or linguistic minorities who bear a strong resemblance to [third world] margin dwellers and are most similar in being divorced from the fabric of cities. Ghettos are separated from the rest of the city by physical barriers such as rivers, railway stations, cemeteries or old airports. The largest, formed because of racial division, is in New York’s Harlem neighborhood. In most of these countries, due to differing processes of transition to capitalism and its growth, poor areas exist, usually in central areas of large cities. Newcomers also live mostly near the central parts of the city. In underdeveloped or developing countries, the margin dwellers do not reside in the city centers but on the outskirts and are scattered in older dilapidated sections. The United Nations has declared slum dwelling “the main challenge of the third millennium”. In my opinion, those driven to the margins by the urban order form most of the working class and play a decisive role in the class struggle between labor and capital in the third millennium, and their “challenge” to capital has begun during the first decade of this century.

Marginalized is a broader category than margin dweller, which in addition to housing conditions (living in the margins of cities), includes substandard and unconventional forms of existence and labor compared to the usual urban and rural ways of life… It could be said that Workers who reside within the unorganized economic and social boundaries of the urban order but have not been absorbed into the standard urban life and economy, and work and live on the margins of the urban populace – within or without the geographical boundaries of the city – are the Urban Marginalized. They are workers who have been marginalized by the paradox of labor and capital without their consent. Then have been socially differentiated by the ideologies of legal-social norms of the bourgeoisie. Their domain includes all those paupers who work; be it productive or unproductive. Destitute people from teachers and professors, engineers and white-collar workers, typists and authors, unskilled and professional workers, house and workshop workers, the workers within bazaars and factories, and all those who sell their labor power [under the mentioned conditions].

In underdeveloped countries such as Iran, the marginalized are generally workers and unemployed people who, according to the above definition, work in spaces lacking official and socially accepted structures and reside in substandard and extralegal housing. Hardly ever are they integrated into the social, economic, and cultural-behavioral texture of cities. They usually lack the privilege of regulated labor (constricted labor and insurance laws), legal housing and traditional public services of each city. Workers who lack the privileges of the urban order, born within this order but exiled to the space in which disorder is born, workers who are exploited by the unrelenting leash of capital, separated from its order during the expansion of the crisis of capitalism and increase in the rate of exploitation, without fleeing the grasp of its exploitation, they increase in numbers, with more disorder and more atomization, continue recreating the relations of production. They are the antagonistic outcome of capital’s logic, who, driven to the margins by the ruthless waves of the decreasing rates of profit, structural adjustment, and economic austerity, numerically increase on a constant basis. Natural disasters (floods and earthquakes) and the ruin resulting from the war with Iraq has taken this increase to the brink of explosion. The majority of the marginalized are workers who in the process of transition from earlier relations of production to capitalism, policies of deregulation of labor and facilitation of immigration in response to the growing disparity between the development of town and countryside, came to cities for selling their labor power and after the implementation of these policies was halted, faced with lack of mechanization of agriculture and limitation of wages and work, and as an unstable population in cities facing weakness and recession of the productive sector and their lack of technical skills, were mostly integrated into the unproductive sector of the margin of economic life. Their slums, dilapidated and old houses, work on the streets (maybe a different phrasing), their four rider motorcycles, running of children in dirt alleys next to piles of garbage, trading of black market goods, the sellers of flesh next to the streets, shabbily dressed children selling flowers in the traffic, individual and ever-moving activists of the virtual world, small smuggler towns that have devoured rural Kulbars [Kurdish smugglers who carry contraband on their shoulders over mountains for trade, this is because decades of deliberate underdevelopment in the area has led to substantial poverty even higher than the rest of the country -KD] for access to black market goods, mobile home dwellers who put their mobile homes in unused or ruined lands within or without cities, the youth who alongside her friends makes decorations out of stones in the basement of a house, all of these are forms of housing and labor outside the usual standards of the bourgeoisie and different expressions of the issue of marginalization. All of them, whether it be in living space and working space or in form and expression, are without privileges. They look eye to eye with drivers of the billion-Toman cars on crossroads, the neighbors in their villas next to their neighborhood; they look at the tidy and ordered city, with their presence and existence they ridicule the bourgeois order. Exploitation of labor power has reached levels that have forced the workers to give up their urban privileges and the urban order by marginalizing their labor, housing and culture.

The majority of the marginalized consist of the surplus army of labor that are usually driven from their homelands to the cities more often because of driving forces from their homeland (unorganized and unstable status of agriculture, unemployment in the countryside, the ruin of war and natural disasters such as earthquakes) and not so much because of any integrating forces [within the cities]. But because of their incompatibility with the urban space on the one hand and repellent forces of the cities on the other, they are rejected. They are either workers who have lost their former standards of living conditions because of an economic crisis, lack of or decrease in wages as well as the extreme cost of housing in the city and have therefore been driven to the periphery to seek cheap housing, or they have an unstable street job on the margins of urban life. In addition to limiting the definition of the marginalized to merely living in illegal spaces, the present bloodthirsty regime has declared places with at least 50000 occupants to be cities to hide the issue of margin dwelling. Because of this, tens of cities have been created on paper and thus the statistics of margin dwelling, according to the government representatives, were limited to housing outside legal boundaries arbitrarily created by them in the outskirts of cities. On the other hand, based on projects named “The General and Detailed City Plan” every few years the boundaries of cities expand and some margin dwellers [technically] become part of the city with the same infrastructure. In both cases, despite the fact that some slums were legally turned into cities, socioeconomic conditions and relations stayed the same and therefore in reality, most cities and towns around big cities are still considered slums. No organization or institute has any official and precise statistics on the margin dwelling population or marginal labor in the country or if they do, they do not publish this data. But according to the official speeches of government representatives just in the area of those marginalized in housing, 3000 slums with a total population of 19 million officially exist but at least 25 percent of the urban population and 35 percent of the total population of the country live outside boundaries and in the periphery (announced by the head of the Social Commission of Majles in 1396 (2017) ). But by considering the falsification of the official statistics and without limiting the definition of margin dwelling to spaces defined by the government, without considering these laws that hide slums in the guise of cities (!) by defining those marginalized in life and labor, these statistics jump from 35 percent to 60 percent of the urban population with variance between different cities but increasing day by day. Meaning more than 50 percent of the population of Kordestan, Kermanshah, Ahvaz and more than 40 percent of the people of Tehran, Mashhad, Shiraz, Zahedan, and Karaj are marginalized. Although official statistics – which are the most conservative estimates – have declared this rate to be 35 percent of Tehran’s population as margin dwellers. Reza Negahban, the head of Road and City Building of Tehran province, during the sixth session of the Tehran Renovation institute told Mehr: “14 thousand hectares of low-quality construction exists in the province of Tehran and the populations that live in these areas compromise 4.5 million people. The sum of all dilapidated and slum housing in Tehran province is 14700 hectares.” These statistics, according to the latest census in 1398 (2019) which shows Tehran to have a population of 13.8 million, compromise 35 percent of the population. (Tehran Statistical Data)

This text’s statistical outlook is defined by the rate of those with partial unemployment which includes all those who are unstably employed. This is done by referring to the statistics on the unemployed and the unstably employed, according to the definition below which covers key factors of the job market, and is called the 12th key factor in [the statistics of] the Statistical Information Organization:

The 12th key factor: “The rate of part time and partial employment mirrors low usage of the productive potential of labor power. Those with part time employment include all those employed who work less than 44 hours a week in a certain timeframe because of economic reasons such as employment crisis, not finding work with more working hours, and not being in a labor-intensive season, while they were ready and willing to do extra work in said timeframe.”

For the official statistics of the unemployed and the unstably employed in Iran we referred to the website of the Statistics Center of Iran as well as the report from the Majles employment commission on the state of employees in the country in the year 1397 (2018) : “The rate of unemployment amongst the youth between the ages of 15 and 24 has been 27.2 percent in the year 1397. This rate has reached 31.5 percent this summer. … in some of these provinces the rate of employment for the educated youth is between 50 to 63 percent and in cases of educated young women the rate of unemployment in these same provinces is between 63 to 78 percent and the rate of partial employment has been between 6 and 10.4 percent.” Therefore, in the age range of 15 to 24 alone, according to Majles, in the year 1397 (2018), close to 33.2% to 41.5% of said population were either unemployed or partially employed.

A few important factors show that because of the methodology in the mentioned statistics, the amount of the unemployed and the unstably employed populations reached in these statistics is much lower than the reality:

- All of those engaged in illegal labor (more service oriented than productive), which includes millions of marginal workers, such as sellers of illegal goods, Kulbars, illegal distributers, unlicensed transporters, and illegal sellers and distributers in general, do not tell those collecting data about their real jobs.

- The timeframe for employment time is one week in which many of those unstably employed who worked for even a single hour in that week have been counted as employed. This approach comes from the definition given by the International Labor Organization (ILO) that defines the employed population in this way: “The employed population: All those 10 years of age and older (or 15 years of age and older) who in a given week, according to the definition of labor, have worked for at least an hour or have left work temporarily for any reason, are counted as employed.”

- According to the cited report “The analysis of the financial situation of the labor force shows that currently, a considerable portion of employees have problems providing basic necessities and minimums of self-preservation. In other words, even though these people are counted as employed according to the factors of the job market, they are no different from the unemployed in providing for their necessities and require attention and support. Therefore, in analyzing the situation of the job market one cannot look at the official factors of the job market alone and assume that by creating jobs and increasing the employment rate, the challenges of the job market have been alleviated.” This means a part of those who are officially employed, even though they are not counted as unemployed or unstably employed, are amongst the hidden unemployed because of their financial situation.

- It is mentioned in the same report that: “One of the most important problems of the current job market is the increase in the inactive population. These are people not counted under the categories of employed or unemployed [because they have stopped looking for work for various reasons]. [This issue] is so severe that in the summer of 1397 (2018), about 60 percent of the population of legal working age were part of the inactive population and the other 40 percent were in the active population.” Part of this 60% who are between the ages of 15 and 24 and are not retired either, should be counted amongst the unemployed and the unstably employed.

If the above factors are considered, the number of the economically active population increases, the number of full-time workers decreases, the number of the unemployed increases, and the percentages of the unemployed and the unstably employed (part-time work with less than 44 hours of weekly labor) increase significantly. It can be estimated that 60% of the active and inactive economic population aged 15-24 are amongst the unemployed and the unstably employed, 80 percent of which is non rural (cities and their peripheries) which is much higher than the official statistics of 33.2% to 41.5%. An important fact is that in all these statistics, in each age [group] the percentage of [unstably employed or unemployed] women in the active population is much higher and sometimes almost twice the average. In the periphery the population of women is higher than men in general. Usually, widowed or divorced women are margin dwellers and work on the streets [and similar spaces], most noticeably as vendors in metros. Recently roaming female vendors who are educated or are university students have also joined them, mostly in metros.

In the latest statistical report from the fall of 1398, similar results have been found but with even higher percentages.

By concluding the above statistical outlook and disregarding the leisure class, the traditional and modern leisurely petty bourgeoisie, as well as the middle classes, exclusively referring to experienced and skilled workers with prior access to housing, employees in higher [organizational] levels and workers residing in company houses who can afford urban life, the rest of simple productive and unproductive laborers who do not have housing [as in owning a house] have either been marginalized or with the continuation of the crisis of capitalism will slowly be marginalized.

Marginal workers are underprivileged compared to and are distinct from urban dwellers in three regards: 1. Habitational, 2. Socio-behavioral, 3. Economic

1. The distinction in Habitation

From hovels, dilapidated houses, huts, substandard mud-brick buildings, half rural homes and humiliating single room dwellings, mobile homes and tents to multi story apartments with small units, unstable structures and plastered walls, undocumented unapproved old and ruined houses, all are examples of the marginalized’s living spaces. The crowded conditions of these spaces, substandard building structures, non-sanitary, dangerous and uncertain conditions, environmental pollution, lack or shortage of public amenities dedicated to these neighborhoods, lack of crucial sewage disposal infrastructure, low quality building materials and dilapidated housing blocs, heterogeneous and overconcentrated housing, the forced acquisition of houses and lands against the law by the government, using prepared mobile homes for sale or rent in ruined areas, living in ruined brick-kilns, all are features of marginal dwelling. From the perspective of architectural texture and city planning, these neighborhoods are formless and chaotic, without official street building and alley designation and instead possessing self-made ones averaging between 2 to 5 meters [in width]. These spaces, from the perspectives of health and sanitation, physical structure, urban infrastructure and public and social amenities are extremely unfit, lacking the structures of standard living conditions and are in clear contrast with the structure of the urban order. An example of this is Oshun Tapeh [اوشون تپه] in Buhman [بوهمن] close to Tehran in which slum dwelling, mobile homes and life without water, electricity and gas remind one of “Les Misérables”. Karton Khaban [a form of homelessness in Iran in which people use cardboards as shields against the cold -KD] in parks and under bridges stick together back-to-back to protect themselves against the cold and Goor Khaban [a form of homelessness in Iran in which people use empty graves as a shelter -KD] are painful examples of this margin dwelling. These slums are constructed illegally and mostly on appropriated land, usually around cities and in an absent owner’s lands, ruined kilns and gardens, abandoned low quality lands, cancelled government projects, uncultivated agricultural of the periphery (outside the [urban] boundaries), lands either lacking [authorization for] housing or authorized but abandoned, and at times within the cities (within the boundaries) but outside planned housing projects and city planning regulations of a given city, haphazardly built, without authorization and without official housing allocation or they fall under the conditions of dilapidated and ruined texture regulation. (Regulations passed in Iran are merely one of the excuses for appropriating people’s lands.) The general plan of the periphery of each city in the high council of urban planning and architecture, controls illegal construction in the boundary and aside from areas that have been designated for housing, such as cities, townships and villages within the boundary, any residential, commercial and service sector construction is counted as illegal and unauthorized. According to section 8 of the Law of Ban on Allocation of Non-residential Areas for Residential Use: “All organizations, institutions and companies providing services for water and electricity and gas and telephone and the like, shall transfer lines and divergences of buildings on the basis of different periods of construction only after building license, license of non-violation or authentic completion license has been provided and transferring the said privilege to residential and commercial units and any building constructed illegally is banned.” “Illegal” and “unauthorized” are also terms that can put the seal of stagnation and destruction on the lands of the destitute within or without the city with a conference by the authorities such as the General and Exhaustive Plan Group or the Article 5 Commission which interpret the laws of Majles in favor of Aghazadeha [those with high-ranking family members or connections in the government -KD] and those related to the regime. Afterwards with another excuse and interpretation and another plan which opens the way for [further] tower building and land owning for Aghazadeha, transfer the lands for an ordered and tidy city.

Rural migrants, alongside their relatives, friends, and fellow countrymen, occupy a piece of land and construct one or two small rooms [for each family]. These are lands lacking the aforementioned construction authorization and the building is done autonomously and the quality of these constructions is dependent on their financial conditions. This attracts other migrants and the urban marginalized to settle nearby. When these areas are outside the legal boundaries of the city, they do not get services nor infrastructural, social, sanitary or educational facilitations. Even the areas that do fall within the city limits have either been integrated by the expansion of the city boundary or with legislation for special cases and possess public infrastructure not comparable and on par with the city or they have been left with the least amount of services and infrastructure maintenance. They have water and electricity and some infrastructural facilities but safety within them is precarious and the method of acquisition of land, mode of construction or lack of documentation and construction license has caused these to be counted amongst half legal residential areas. In these areas, people are in a constant struggle with the government because of poverty and financial struggle which cause issues for paying the bills for water, electricity, and gas, or the reconstruction of their homes and they share these struggles with the margin dwellers outside the boundaries. Their motorcycles have been repeatedly stopped [and usually confiscated -KD]; Their goods have been stolen while doing Kulbari; They have been arrested countless times for vagrancy when doing roaming jobs [e.g., street vendors]. Whatever cheap corner they rented, they were driven out of for not being able to pay for repairs and bills. They were gradually driven out of the city and lost access to many of its facilities. In the last few years, margin dwellers have resorted to using tents and mobile homes, and even though no official institution has published statistics in this regard, the internet is filled with pictures of relatively large families living in mobile homes and tents. These mobile homes have no title-deed, therefore real estate dealerships are barred from creating contracts for them for buying and selling, mortgage, and renting. Some reports have mentioned the unofficial sale and purchase of mobile homes given to those affected by earthquakes. Excessive migration and the increase in rent have forced many to use mobile homes within cities, and tents outside the boundaries, and these factors are still in effect. According to a member of Majles: “The increase in rent prices has created such a [severe] problem for people that they can no longer afford it to an extent that many citizens have called me asking for provision of tents from Helal Ahmar [Islamic red cross] for survival by camping in the parks, this is so severe that it should be considered a national crisis.” But slowly, even the rent prices on the lands these mobile homes use, will become unaffordable. They prefer to use tents or mobile homes outside the city and its boundaries, because not only are rent prices for their mobile homes’ land too high for them, but they’re also unable to gain access to water, electricity and gas officially within the city. The well-known tent dwellers of Bandar Abbas, also known as Hashieneshinan-e-Posht-e-Meidan [margin dwellers behind the square], don’t even have identification, and reading the stories of their lives within the “golden gate of the national economy” (according to the authorities!) is heartbreaking. One of them says: “Our girls and boys usually marry at the age of 15. Here amongst ourselves they fall for each other and the ceremony of asking the girl’s hand in marriage ensues. A lot of the time the girl doesn’t have any ID and the boy does or neither of them do. Because we know nobody will do anything for them, we have a marriage office we know that makes 99-year temporary marriage contracts for them, although the conditions for cases in which neither side has any ID is hard, and their children will not have IDs either.”

The urban planning organizations of the Islamic government, in the interest of the power of capital and the family of Velayat [the Islamic clergy with the supreme leader as the main figure] has made cities the pillaging ground of towers and shopping complexes presenting foreign goods by issuing inappropriate usage permits [residential, commercial, industrial, etc.], creating instant permits paid for with money [and without considering any quality control measures] and construction without proper prior planning, which causes daily increase in the cost of housing. Through this process, currently not many workers, containing even university professors, school teachers and educated skilled workers, have the ability to afford housing within the city. The only people mostly unaffected are the upper middle classes, the leisurely petty bourgeoisie and capitalists. It is feared that within the not-so-distant future, for the exception of workers living within company houses or workers with one child who inherit housing, the rest have no solution but to reside within the periphery, not just for housing but even for decreasing the costs of living. Ali Alipoor, the head of the organization for co-ordination of the redevelopment of Tehran province, said in the Tir of 1398(June 2019): ” One of our main problems when dealing with unauthorized dwellings is that the residents have no motivation to changing their life and tend towards living in mobile homes and slums. Our efforts in Oshun Tapeh [اوشون تپه] towards moving individuals and giving them a better life faces disinterest from the residents of these areas. As another example, in Qods [قدس] and Malard [ملارد] divisions, we have provided accommodations for converting temporary ownership documents to permanent title-deeds; but the residents have no interesting in converting; because they fear they may have to pay taxes, bills, etc.” (Fararoo website)

In many areas within cities, there are dilapidated blocs in old alleys with unsafe foundations or without title-deeds and construction permits, whose owners are destitute and unable to reconstruct or even repair them. For these areas, improvement, construction, reconstruction and restoration projects have been put forward by the Housing Ministry as a complete plan for part of the city’s existing blocs. The mayoralties use these plans to pressure people living within these areas to demolish and rebuild their homes in accordance with the new laws, or to make them leave with the excuse of broadening alleys. These living spaces, however, are not restricted to areas outside the main boundaries of the city or old neighborhoods but exist within the boundaries and texture of the city and even in wealthy areas. In Tehran, one can point to Deh Vanak (ده ونک), Farah Zad (فرح زاد), and those living on the margins of Sa’adat Abad (سعادت آباد) such as under Modiriat bridge, that like red dots, are out of place within the urban order, and for decades the armies of the mayoralty’s order have been in constant war and skirmish with them, trying to drive them out for the sake of an orderly city. Those who are being cleared from Farah Zad valley these days (Azar 1398/ December 2019) were cleared many times in the past. They had no choice but to go to Farah Zad valley or Baqer Abad(باقرآباد), or to Qarchak(قرچک) and the surrounding lands. They increased each year in our beautiful cities, in Mashhad(مشهد), Shiraz(شیراز), Karaj(کرج), Tehran, Kermanshah(کرمانشاه); But we didn’t see them. The Iranian Arabs dislocated by the ruinous war, sat in an unseen corner of Hafez’s beautiful Shiraz; Hidden from our view, lest they disturb our enjoyment of the flowers of Eram(ارم). Their street shops have been violently torn down, lest they stain the beautiful bazaar of Shiraz. We didn’t see them, didn’t hear them, their public outcry in Aban was needed for us to hear their voice. An Aban was needed so that they could, with their fury, strike the face of the urban order like a flood and announce their presence and existence.

Margin dwelling has entered the underground housing market as well, an unofficial market alongside the market for purchase of other commodities. This market exploits workers and the unemployed, chained by the commodity economy of government connected land rentiers. So that, when margin dwellers, because of unemployment and low wages, are thrown out of cities and villages and with no way to recovery, they go outside the boundaries and flee to lands without owners to build huts; Besaz Befroosh Ha [capitalists who buy lands and create low quality housing which they sell for a huge profit and then move on the next land to repeat the process, they’re notorious for horrible treatment of workers and outrageous prices of their buildings. This is a viable business strategy as the government is very favoring of landlords and real estate developers and traders -KD] and landlords connected to the government that had previously made them homeless, are waiting for them.

A margin dweller has been quoted in “Report on the Dilapidated Texture of Jiroft(جیرفت)”: ”In the past, an individual named Sepahbod Vafa, who owned many lands (let’s not discuss the issue of how he acquired these lands) split his lands into smaller portions and sold them, because this way he would earn more. The main issue is that he split these lands with minimum possible pathway allocation which is against regulation and started selling lands with areas between 12 to 45 [square] meters. We even have 18-meter lands in this neighborhood! Even 12-meter ones! A section has been allocated as the living room and another as the bedroom. A bathroom in the corner of the yard and right next to it, the housewife cooks food and that’s it. The alleys are so narrow that two people can barely pass by each other. We’ve been wanting to coat our alleys with sand. But we haven’t been able to gather enough money in two months. On rainy days our children face many issues; and the mayoralty doesn’t do anything. They say: “This isn’t within our jurisdiction. You’ve built it without permit.” We don’t have water; we take electricity from the cables passing by our neighborhood. But the residents are okay with that. Sometimes up to 20 people live in the same 18-meter space.”

A citizen commented in the Meidan website [Meidan is a left leaning news website with the aim to deliver news that doesn’t pass the government’s censorship filters. They mostly focus on the condition of the working class. -KD]: ”The people of Farah Zad who stood alongside the revolution with their lives have always been oppressed, the least I could ask for is to get to live in my own birthplace, in the land of my ancestors. Who is behind the gigantic Zamin Khari [Government connected individuals overtaking vast swaths of land usually from nationalized resources or working-class neighborhoods with existing owners who are driven out of their homes -KD] in Farah Zad? They don’t let us work on the lands we’ve inherited from our ancestors so that in the end it becomes barren, then the mayoralty can easily expropriate them with the excuse of not having title-deeds. When a Farah Zadi can’t build a room in his own land, they build towers in their expropriated lands and don’t even give a single flat from the thousands of flats built to the original owner of the land; and when, with the excuse of river boundaries, they take the same gardens they dried by cutting the water years ago, they don’t give any money to the real owners.”

2. Socio-Behavioral distinction

Amongst the margin dwellers and marginal workers, lack of safety, social injustice, and issues in their social, habitational, and work spaces, creates social behaviors distinct from urban society. This makes them less accepted by legal and legitimate citizens of urban society. Villagers with limited education and alien to urban behavior, and ethnicities with differing traditions and cultures, are the primary subjects of these marginal lives. The marginalized of the city and village, even when they enter the legal boundaries of the city or legal work, still noticeably differ culturally from city dwellers in sociocultural (language, living with extended family and people of the same ethnic group, not paying mind to the laws of traffic and cleanliness in the city) and economic (high concentration of population, cheap housing, clothing and home appliances) aspects. In addition to class, ethnic, ecological and sexual injustice, they especially suffer from humiliation inflicted by city dwellers and the feeling of exclusion from the city. A kind of humiliation that has its roots in sociological theses and [now] exists amongst different classes of the city, even those from the same class dwelling within the city. The condition of margin dwelling is an undetermined condition as it relates to the city that puts individuals in a suspended state, socially and culturally. It is both urban and not. Both different and at the same time very much imitating.

Through the expulsion of the marginalized from the city and the increase of their proportion in comparison to immigrants in the population of margin dwellers, some of these cultural differences are reduced over time. And the immigrants, through their presence within the city for the purposes of work in the economy, shopping or insignificant entertainment befitting their wallets, especially addiction to the internet, are slowly integrated into urban culture. In regards to the margin dwellers living within the texture [boundary] of the city, these cultural transformations happen more quickly and to a higher extent due to cohabitation with the middle classes, professionals and their own children being university students, to such an extent that they become one with the urban working class, and their cultural differences are reduced to the general class distinctions of the whole of the working class.

Due to absolute poverty and extreme deprivation, they’re also defenseless against any social harms and very susceptible to harm. They are affected more than anyone else by social harms and ills, behavioral issues and they’re more likely to get involved in criminal activities. Therefore, their neighborhoods are the center of many social harms. Being on the periphery of labor and life, creates subcultures with norms and values that come with social deviations and other properties such as social isolation. Because not only does poverty create social harms within its context, but more so because criminals can hide themselves from the eyes of the law in these peripheries. Creating disturbances; many kinds of theft, collective disputes, addiction, drugs, vagrancy, the hiding of urban criminals and those who in the name of coercion (theft by threat of violence) recruit and gang wars, bands for begging, prostitution, and sale of stolen items are seen more frequently in the peripheries. The biggest problem for these areas, are bands of beggars and drug dealers that threaten the mental and spiritual health of the residents of these areas. So much so that parents are always afraid of their children going outside, in fear of them meeting these harms and threat or encountering bands of criminals or coercers. Bands which go to these areas, to be outside the authority of law. But unfortunately, the same problem has become an excuse for the government to purge the margin dwelling areas of the city. Propaganda about the unsafety of old areas with the purpose of creating a picture in the public consciousness that these neighborhoods are the center for the gathering of addicts, drug dealers, and urban criminals to prepare the mental context of society for the destruction or purchase of these lands with the lowest possible prices. The Meidan report on the project for purging Farah Zad valley in Tehran is an interesting read; or reports on addicts in this valley, or the prostitution of homeless women, after Aban 1398, shows the erasure of the question [instead of providing actual answers to it] by the usurpers of the right to live for the same sufferers whose story has been repeated and will be repeated in Niayesh, Deh Vanak, Modiriat Bridge and many areas outside the order of capitalism.

A citizen from said report says:

“The quality of life in this area is very low and the houses are dilapidated, and because they don’t have title-deeds, they weren’t given construction permits; the houses have been built two to three decades ago and at times repaired with materials such as clay, tin, or metal beams. In front of many car repair shops under Modiriat Bridge or Niayesh town, the mayoralty has put concrete barriers because they didn’t have work permits. At night, bands of vagrant boys are seen roaming the streets. The lifestyle has caused most to turn to drugs and crime. My aim in talking about this situation is to show that this issue should be deeply analyzed, and one can’t tell right from wrong by writing a short text. This text is about the purging of Farah Zad, however Modiriat neighborhood suffers from the same issues. The discussion shouldn’t be centered around the likes of me, as someone living in Fargang boulevard, not wanting my windows to have a view of this area. The issue should be resolved, not the erased. Throwing these people out by buying their houses with low prices (usually between 70 to 150 million Tomans (5,000 to 10,000 dollars at the time of writing, which is 2020, and 2,500 to 5,000 dollars at the time of translation, which is 2022) is offered by the mayoralty) not only is inhumane and immoral, but it also worsens the issue. I, as someone living in Farhang boulevard, would like my surrounding urban blocs to meet basic requirements. The reality is that the underside of Modiriat Bridge and Deh Vanak are comparable to Ure village (the only village I’ve ever seen) in quality of construction. The quality of apartments is on such a level. Houses with one or two floors, very poorly made and with visually unpleasant constructions materials; Low priced and illegal rent that attracts anyone engaging in illegal activity. All these together make these two neighborhoods a magnet for drug dealers, addicts and prostitutes, drugs producers and low-income migrants, etc. By blocking their shops and not giving social services to residents of these areas, the mayoralty forces them to accept their offered amount and by doing this, “purges” the area as they call it themselves, making a very profitable revenue of income for this organization. I’m feeling sorry for the poor people of this area who, even if criminal or even if engaging in illegal activity, still have no other way to sustain their livelihoods. I’m deeply saddened for them and unfortunately as the author [of the original piece being quoted here from Meidan] said, the right to citizenship is left only for the owners of towers who have paid not those who live within the city…”

3. Economic Distinction

It has been less than a century since margin dwelling gradually became a destructive and unstoppable force to order un undeveloped countries. Some governments, which have tried providing housing by creating towns to hide this phenomenon from view, have failed to integrate them into urban economy and society because of the context of the struggle between labor and capital. (In the year 1344 (1966) around 3400 residential units were built in Tehran’s “Kuy-e-Noh-e-Aban” which was renamed to “Kuy-e-Sizdahe-Aban” after the 1979 revolution. Or the preparatory-research project of the year 1350 (1972) in a few cities, or the ruined “Maskan-e-Mehr” project after the revolution!)

The urban marginalized generally form lowest levels of labor (on the basis of education, skill and income) and usually have higher education rather than technical skills. Selling labor power below the poverty line, lacking work stability, and working outside the boundaries of labor laws, lacking the usual standards of work is common amongst them. Their incomes are low and not enough for their livelihood. In some cases, the income of the family is so low that they have to go towards selling their organs (kidneys, hearts, and eyes), selling themselves [prostitution] and sale and distribution of drugs. In recent years, with the increase in the rate of exploitation, the educated, teachers, office workers and technicians have also been driven to the margins of street work without legal status or poor neighborhoods without the privileges of normal living spaces. The policies of economic austerity also drive them out of the city and at the same time integrates them into the unofficial commodity market and underground production of said city.

The properties of marginal work:

A) The first distinction is their lack of officiality, either their habitation is unofficial (margin dwellers) or their labor (marginal workers). Some have called them “the unofficials”. Workers lacking urban privileges, workers who lose or have lost their right to the least of city life because of increase in the rate of exploitation. B) Most of the workers are unproductive. A small number of them are productive workers who are mostly working in underground workshops; even fewer are simple workers of big factories with work contracts, obligatory insurance and with the standards of urban work. This minority are not marginal workers and fall into the category of official labor, however, they have been made into margin dwellers. In addition to workers, minor contractors, shopkeepers and small merchants who have risen amongst this class and slowly built up some capital for themselves are also present in this categorization. C) The absolute and the hidden unemployed who fall under the category of unstable workers. Unstable workers usually lack group work and social cooperation. The period of their employment is short, at the very most a year – more often irregular intervals–, and at the very least a few hours. They change their jobs based on the season and conditions or must leave work when the employer doesn’t need them, or they must find better work. They usually don’t have specific employers and when they do, it’s usually a real person and less often a legal entity. The vast majority of unstable workers do not have work contracts and insurance and don’t fall under the protection of any organization, and sometimes their income is lower than even that of a simple worker [meaning they make even less than minimum wage which is already an abysmal amount and much lower than the poverty line -KD]. This group can be called peripheral workers because of their lack of privileges offered as opposed to official laborers, workers who sell their labor power unofficially. Most of them are marginal street workers; workers, abandoned, unemployed and looking for a bite of bread.

Unstable workers themselves fall into two categories: C -1) The group that has legal but unofficial work [meaning they don’t conduct illegal activity, but they don’t fall under laws protecting workers either -KD] but because of the constant need of capitalist class they’ve been accepted into the standard order urban labor. Generally they don’t have work contracts or obligatory insurance and few of them are insured, depending on the employer’s fairness; examples include house cleaners and gardeners, superintendents, in-house nurses, travelling traders, providers of necessary commodities and services – such as taxis, blanket weavers – brokerage, unofficial/part-time taxi drivers, carriers of goods on their backs or wheel carts in the bazaar, foundry workers and vendors… C -2) A group of unstable workers labor not only unofficially but also illegally. They are the workers of the so called underground or hidden economy. This group does not have work contracts or obligatory insurance. Their work is considered criminal and outside the standard realm of urban labor, the streets being their primary workplace. Because of their constant struggle with the henchmen of the urban order for the maintenance of their livelihoods, they’re called street workers, or as Asef Bayat calls them, rebels of the street. Such as: vendors on walkways, inside the metro and the city’s public buses (Dast Forooshan), those who transport deliveries or passengers with their motorcycles for a living, beggars, workers active in the black market (commodities, narcotics, currency and services), workers active in underground production, prostitutes, thieves, child workers, Kulbars, car repairmen on the side of the streets as well as those employed in smuggling, debt collection, trading of stolen and illegal goods, distributing illegal commodities. Without a doubt, these actions are not limited to margin dwellers. Iy also involves workers belonging to urban life. However, unprivileged workers in Iran, after the sanctions, because of absolute poverty and the need to earn money for the continuation of their lives, are the most expansive group of laborers amongst the margin dwellers.

Cities face people whose whole lives are defined by the grey highlight of life in the periphery; people who are born within the margins of the city, live in the margin, breathe in the margin, work in the margin and die in the same margin; people who know, even if they struggle all their lives, they will never reach the core of the city. They are the Humans of Aban. Those who in the last week of Aban felt the attack, ridicule and shaming of their children and their homes at the core of their beings. Those who, without hope for a savior, stood on their own feet, those who in face of the enemy’s onslaught, forgot that they’re Turks, Kurds, Lors, men and women, and stood beside each other to watch out for each other with all their ability, those who despite the banning of worldwide internet, without the mosques and religious centers supporting the Islamists in 1979, took the class struggle to more than a hundred cities. Even though three special qualities in the forms of work and life differentiates the marginalized workers from classic workers, they, more than any distinction from classic modes of social production, embody the destitute owners of living labor and a huge section of the working class.

“Classes, identities and organized masses are not abstractions: They are shapes of the world’s collective experience that are created on an expansive scale. The same way they chose accidental shapes a hundred years ago, now once again they do the same through unpredicted and often fascinating paths and reasons that are very different from the past. We shouldn’t confuse social class – a way to statistically categorize individuals based on property, resources, access to wealth, etc. – with practical ways which are categorized based on specific solidarities, place of residence, shared issues and cultural qualities. This is a real movement based on the shifting position of classes which correlate only through accident or places of similarity in statistical data. The problem of the traditional left is that it mistakes “proletarian conditions” with a specific historical shape of wage labor.” (Linera, Ibid)

- This refers to the categorization of Kukh Neshinan (slum dwellers) and Kakh Neshinan (palace dwellers) Khomeini used to replace the proletariat and the bourgeoisie by trying to present himself as a socialist in the model of people like Ali Shariati -KD

- A notoriously unsafe Iranian car used by many because it used to be the only affordable option for most families. After the recession and sanctions, even this vehicle is no longer affordable for the average Iranian family. –KD

- The literal translation of this word is “oppressed” but the word carries a different meaning these days because the Islamic Republic’s leader has frequently used it to describe the allies of his own state and has insisted many times that it doesn’t simply mean the poor. This will be further discussed in the text. –KD