Drawing from the experience of the Democratic Socialists of America and Marxist Center, Marisa Miale examines the everyday, interpersonal level of party-building and argues for a revolutionary strategy that can weave together cultural intervention, base-building and political unity. Reading: LC.

“They all leave something behind, and the next great movement like this one that comes, simply steps into the footsteps of those who have gone, and carry it further until the emancipation comes. It is a lesson of history. We do not accomplish all in one day, or one generation.” -Lucy Parsons1

A New Party

Observing the state of the communist movement, it can be hard to imagine that our atomized mass of people, intervening in the class struggle alone or in small collectives, could ever cohere into a force capable of challenging the extant ruling class. New and hopeful socialists find themselves demoralized by interpersonal conflicts and political inertia. In 2021, at least two North American socialist formations—Marxist Center and the Democratic Socialists of America—faced escalating conflicts which came to light in the middle of their conventions, damaging relationships between their members, limiting their momentum, and in the case of the former fragmenting it beyond repair. While it’s necessary for us to face conflict directly, our means of handling it often does more to disorganize than unite us.

Without a clear way forward, we tilt left into daydreams about spontaneous uprisings, or right into the service of liberal reformers. Many revolutionaries react by framing our problems as insurmountable, as if the underdevelopment of the Left and the low consciousness of the working class is a trap that can only be escaped through splitting into a purer body or by fomenting an organic working-class movement independent from the Left. In his overall poignant reflection on the dissolution of Marxist Center, comrade Tim Horras blames most of the network’s failures on the activist left, a term which remains undefined but seems to encompass any political organization that did not emerge directly from the autonomous struggles of the exploited, i.e. all of us. Instead, he suggests that Marxist Center’s milieu should have focused entirely on building up “nationwide tenants and workers associations,” before a revolutionary political party.

Examples of revolutionary movements which put off the development of a national or international political movement, however, remain few and far between. If socialists are to be of value to the movements of the exploited and oppressed, we owe them a clear political vision and expansive organization capable of uniting their struggles, defending them against state repression, and putting the tools of socialist construction in their hands. We cannot bypass this by diving harder into sectional organizing like the tenant and labor movements, as necessary as they may be, without organizing our own scattered forces into a unitary formation. Bertolt Brecht once joked that it would be simplest for the German Democratic Republic to “dissolve the people and elect another” after losing the public’s confidence.2 Like them, we do not have the luxury of discarding the hand we’ve been dealt and drawing another. We must work with what we have.

Instead of seeing the failings of the present-day Left as entrenched barriers, what could we do if we reframed them as solvable problems? If we enlist as many comrades as possible to work through them, not only can we succeed at correcting the course of the Left, but we can develop some of the skills and analysis we will need to construct a socialist society. Rather than being a barrier, what if we approached the revolutionary milieu and the dispossessed class as the raw material of a conscious, active instrument of class struggle—which is to say, a new communist party?

For some among us, the term party evokes the sectarian politics that has haunted the Left for decades. But finding the common ground for a party doesn’t mean creating a perfect replica of a Marxist-Leninist cadre party or Social-Democratic mass party. The Communist Party represents the revolutionary layer of the working-class cooperating via their shared interests and reflects as much as possible the breadth of the entire class. The agency to shape the party is in the hands of living communists, with its form and content belonging only to us and the material constraints history imposes on us.

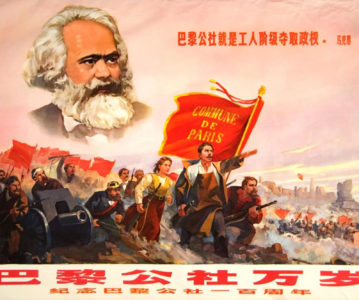

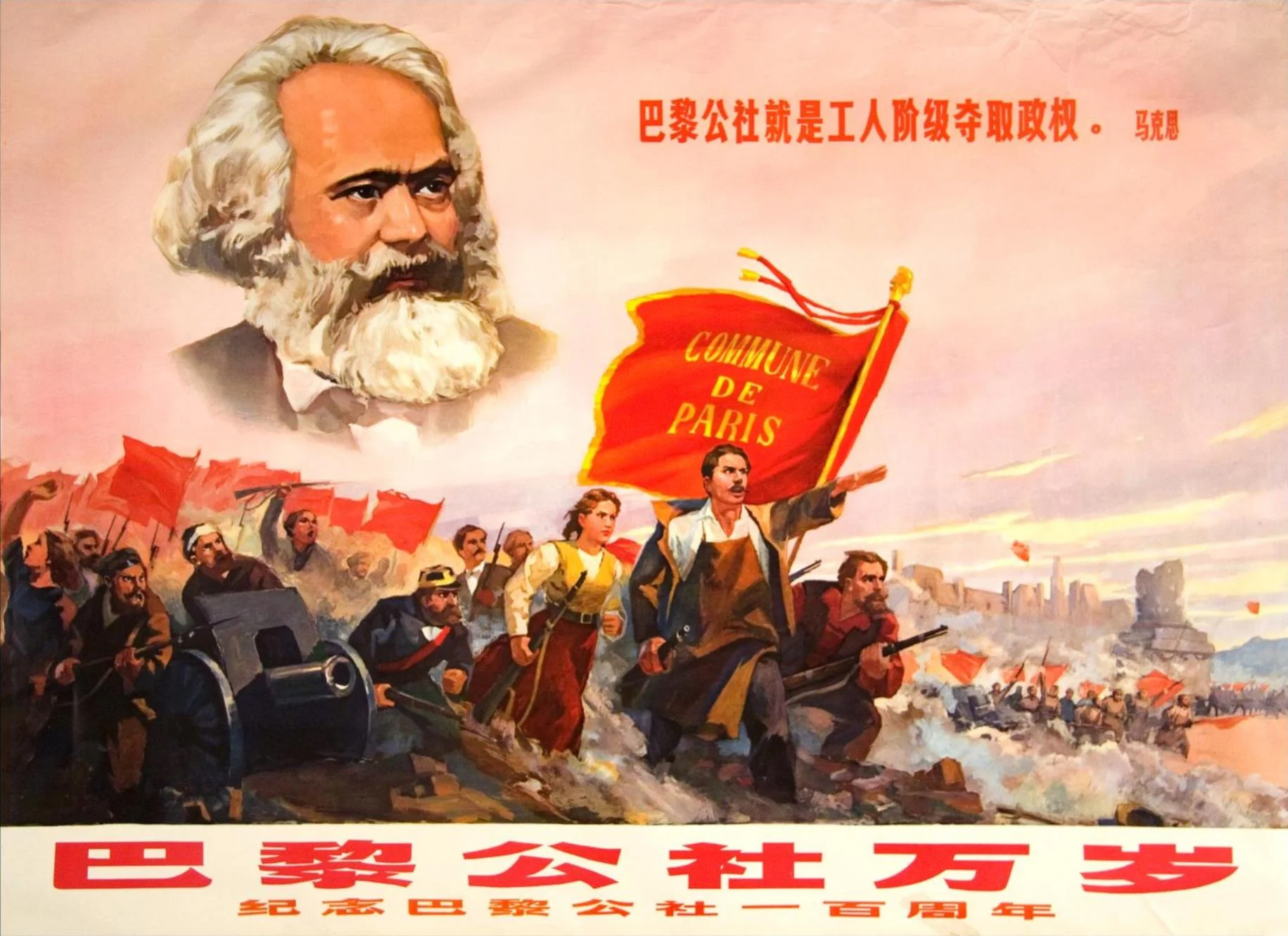

Marx once referred to himself as part of the historic party, the networks of cadre who keep the class struggle alive between moments of upheaval and transmit communist theory from one generation to the next. While the formal parties we create may come and go, some remnant of the historic party always persists.3

In the Left Communist lineage, the historic party refers to those who adhere to an invariant Marxist doctrine without allowing for correction or adaptation.4 Here, however, we will reclaim it for a different kind of Marxist: those who use Marxism as a living science, researching shifts in the capitalist terrain and experimenting with new methods of fighting that build on the old. In the core of the historic party, as we define it, are the communist militants who intervene in the daily struggles of working-class people, mobilize in uprisings and study the contours of capitalism. At its edge are the relationships communists form with others—collaborators in action, contacts from canvassing and outreach, public sympathizers, family, and friends—all of whom can be pulled deeper into the movement or convinced to become communists themselves. Further out are those removed from the Left, some of whom may be contacted through outreach and some of whom may activate and come into our orbit during moments of crisis. In periods of retreat, the numbers of the historic party will contract, with networks straining to recruit and maintain their contacts. In moments of mass inspiration or uprising, volunteers will emerge even from outside our established networks.

Communists need to understand our relationships as the foundation for something greater than the sum of its parts. Building a party is not just the visible sequence of holding a founding conference, picking a name, and writing a program, as vital as those steps might be. It is a constant process expressed in every knock on a tenant’s door, political conversation, organizing lesson or book lent to a comrade. The more partisans we draw in and develop, the sharper our collective expertise, and the tighter our bonds with each other become, the stronger the formal party we come to inhabit will be.

When we act as communists, we need to ask what lessons those around us will take with them. When we encourage splitting or purging to purify the movement, are we replicating a pattern of self-sabotage going back generations? When we yell at comrades instead of educating them, are we teaching them that lashing out is acceptable? What relationships do we need to build, and what capabilities do we need to expand?

These questions are most often answered through organizational discipline, with the party holding members accountable to its expectations and needs. We don’t have room here to explore all of the possible nuances of discipline—which can look like everything from cultism and micromanagement to democracy and accountability. Rather, we will consider how we can create a culture of discipline with the present amorphousness of the Left. In the absence of a formal party where communists can harmonize and hold each other accountable, we owe fidelity to the historic party and its transformation from an atomized, swarming mass into a crystallized and self-aware bloc. Through cultural intervention—the practice of directly addressing social problems within the Left and helping each other learn from mistakes—we can till more fertile soil for the formal party to grow.

This is not to say we should reject any kind of order of priority, or to reframe organization as being about individual rather than collective relationships. Rather, my intention is first to find a place for our everyday interactions in the process of party-building, and second to develop an ethic of responsibility, not just to the success of a single-issue campaign or an ephemeral formation, but to the communist horizon itself, and to the comrades with whom we walk toward it.

The following sections are a synthesis of lessons from engagement in mass work and participation within the North American communist milieu that has emerged over the past few years. They are drawn from study of past efforts at revolutionary organizing and the beginning stages of social practice, particularly the last year of Marxist Center’s existence. We will examine how communists can draw from past incarnations of the movement, how we can develop our interpersonal relationships, how we can understand state repression, and lastly tie these elements together in the formal party. My aim is to help communists contextualize their own experiences of growth, friction, and adversity within a broader project, owned in part by all of us. After the initial fervor of radicalization wears off, it becomes difficult to remember the purpose of our actions and commitment to the class struggle, requiring us to look to the bigger picture to carry on. With hope, this will help communists understand the potential reverberations of our daily activity and spark a broader conversation on revolutionary strategy.

The Old Party

We are not the first to march toward revolution. Nor would we be the first to declare that we intend to build some form of party and to crash and burn on the way there. History is littered with people like us who have tried and failed. In the grand scheme, even the most advanced and influential formations on the Left have failed in achieving their ultimate aim, as evidenced by the more-or-less intact capitalist world-system we still live under today.

In the wake of the uprisings of the late 1960s, thousands of Americans found their way to the communist movement, which was at that point lost and confused by its own failure. While most of their elders in the old parties alienated the new generation, the newly radicalized youth of the sixties nonetheless took the theory and methods of communism and made it their own. Grounded in Marxism, they fought police occupation in the city, speedup on the assembly line, and Empire in Vietnam.

In the blink of an eye, they built an army of revolutionary collectives, held dozens of unity conferences and debates, prepared for a civil war, and then dispersed in a haze of exhaustion and repression. Max Elbaum, a veteran of this period, calls it the New Communist Movement (NCM); when a surge of young radicals took up the task of building a Marxist-Leninist party from scratch.5

One commonly-repeated lesson gleaned from the NCM is that returning to orthodoxy will never be enough. Aspiring partisans in the NCM identified revisionism, the Soviet-sponsored Communist bloc’s turn away from proletarian revolution and toward socialist realpolitik, as the primary failure of their predecessors. In response, they went out in search of an unfiltered doctrine that only needed to be rediscovered, not developed. While more nuanced and innovative currents emerged from the NCM, at their most dogmatic they believed that the works of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, and Mao held most of the answers they needed.

All of those thinkers, however, wrote in response to the conditions of the world around them and adapted their approaches in response to changes in those conditions. Lenin, for instance, constantly shifted his stance on organization and tactics based on the ebb and flow of revolutionary energy in Russia, changes in the legality of socialist politics, and events like the first World War and the founding of the soviet system. Mao tried to adapt Marxism to the Chinese peasantry, which became gravely important when the Chinese communists were exiled from the cities and could no longer build a proletarian base.

It would be an overcorrection, however, to say that just because no past dogma can save us, we have to start from scratch in every new moment of history. The ruling class continues to rule because they adapt to new circumstances, using the intelligence and infrastructure they’ve accumulated for centuries to chart new paths for the survival of capitalism. So, too, must revolutionaries retest old theories and synthesize them with new ones.

Most of the NCM disappeared into either the industrial world they infiltrated or the professional world they’d sworn off, abandoning their revolutionary aspirations. But the NCM does not belong to some discrete epoch before us. The historic party carries on, delivering fragments of its experience from 1968 to 2022. Some of us know them as thoughtful and experienced comrades who held on through decades of reaction, eager to share lessons on the exact problems we grapple with today.6 Others we know as sectarian ghosts, carrying the same signs at new protests year after year.

While the NCM was a confident break from the fading Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and Socialist Workers Party (SWP), a fraction of radicals among the old guard found hope in the new wave of leftists. Former official-Communists like Harry Haywood and Ted Allen and Trotskyists like Hal Draper nurtured the development of revolutionaries in the NCM. This was not a new phenomenon—years before, unionists in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) like Lucy Parsons, James P. Cannon, and William Z. Foster joined the Communist Party as it entered center stage. While the IWW, CPUSA, and SWP all failed to overthrow capitalism, their members acted as links in the historic party leading to the NCM and to the movement today. Instead of just indulging in romantic or bitter memories disconnected from the present, they left a complicated legacy that ensured a cluster of socialists could continue their work in the future.

Our movement must account for what experiences, ideas, techniques, and infrastructure we can scavenge from the ruins, especially while living participants from the last widespread party-building moment are still with us. The same must be said for the alter-globalization protests of the late 1990s, the anti-war movement in the 2000s, and the wave of uprisings starting with Occupy in 2011 and leading to the present. A million red threads weave these moments of rupture and consolidation together. Some may fray, but the entire tapestry has never severed. While it can be tempting to see the formal parties which collapsed or tilted right as abject failures, all of them played some role in helping the historic party expand its ranks and accumulate data on capitalism and class struggle.

It seems statistically inevitable that most of the structures we work through now will be just as ephemeral. Sectarians make the mistake of thinking that because they have the correct ideas, their parties are preordained to be the vanguard of revolution. Those in the right-wing of the Democratic Socialists of America veer in the opposite direction, deferring to coalitions with liberal activists. But agnosticism about our own importance can be freeing. Instead of assuming our own importance or lack thereof, the vanguard of today should work to raise the power and organization of the entire working-class, dissolving our position at the forefront by developing a mass vanguard.

Future generations will be operating on devastated terrain because of the uninterrupted advance of climate change. Some fragments of our experience can be preserved, and some may be lost to time. A fraction of our current cadre will continue forward to train, teach and mentor those after us, but burnout and alienation could claim many others. This is why summation and theorization are so valuable—just as we learned from narratives and observations of those before us, we need to record our own for each other and those taking up the charge after us. We are writing ourselves out of the story when we view theory as something created by the successful but dead revolutionaries of the past and practice as our application of it. Instead, both are continuous processes we all take part in, and which we have a responsibility to share with each other. To be able to pass on as much as possible, we need to develop practices that preserve relationships between cadres and create more durable and self-replicating structures. This will require looking at past incarnations of the party and understanding what it left us and how it did so.

Among Our Friends

In her essay Four Theses on the Comrade, philosopher Jodi Dean defines comrades as those with whom “you share enough of a common ideology, enough of a commitment to common principles and goals, to do more than one-off actions. Together you can fight the long fight.”7

For her, comrades are necessary for the revolutionary movement. We cannot overthrow capitalism as disconnected individuals, all spontaneously coming to the same conclusion and acting in the right pattern to create a communist society. Instead, we learn, teach and act together in a vast web of comrades across the world. Having comrades is a comfort because it means we never act alone. We can trust comrades to catch us when we fall, push us forward when we pause, and advise us when we’re lost. We don’t have to like them as friends, we just need to understand that our fates are tied. We should keep in mind, however, that comrades are not merely an asset belonging to a single revolutionary leader. We have an obligation to show up for each other and treat each other with respect—not just because it’s the moral thing to do, but because it’s the only way the historic party will survive and grow. Most people will only accept being taken for granted or mistreated for so long. Comradeship only works if we have a responsibility to each other.

Dean follows Bolshevik leader Alexandra Kollontai, who theorized that societal concepts of love are based on their mode of production. Just as feudalism and capitalism had distinct forms of love and relationships to meet their needs, the emerging socialist society would develop its own. She believed this would take the form of love-comradeship, a sense of duty to the will of the collective that could wash away selfish individualism while allowing for a higher sense of mutual respect and sensitivity toward each other. This meant that communists would need to embrace “‘warm emotions’ [like] sensitivity, compassion, sympathy and responsiveness,” using them as tools in the construction of socialism. This may resonate with organizers across different fields. While organizers often emphasize anger at the boss or the landlord, agitation can only turn into organization through deep relationships and trust between those with common enemies.8

However, comradeship as Dean describes it is an ideal divorced from how leftists treat each other, and even the revolutions of the 20th century only scarcely began to chart out the reality of love-comradeship. The norms most of us are familiar with are scorn over differences of opinion, dismissal of the misinformed or undereducated, and either the exclusion or tokenization of the oppressed. Taken together, we often name these problems bluntly as uncomradeliness, wherein comrades are treated like either objects to be used or enemies to be torn down.

A common mistake socialists make is to overcorrect from these issues, identifying conflict itself as the problem. When we refuse to engage in conflict with each other, we immobilize ourselves. All decisions require open, honest exchange on the right course of action. Otherwise, we force individuals to make their own calls without feedback or oversight. Eventually, suppressed conflict bubbles over anyway, leading to shouting matches, bureaucratic maneuvers, and splits over issues that could’ve been hashed out constructively.

These problems were not generated by the Left in isolation. We learned most of them growing up in capitalist society, watching these dynamics play out between bosses and workers, landlords and tenants, men and women, settlers and the colonized. Conflict avoidance is a common way of coping with mistreatment, especially when there are no political channels open to fighting back.

We carry what we learn with us, replicating these behaviors in the movement. But the movement is also the perfect place to start unraveling them, surrounded by comrades who recognize these issues and have the grace and determination to deal with them. This is not to say that all problems can be solved internally—most of our organizations, for instance, do not have the capacity to reform perpetrators of sexual assault, necessitating expulsion to keep our members safe. But we are well-equipped to make an intervention against exclusion and objectification.

The NCM faced the same issues, with aggressive line struggles, contests of ego, and accusations of bad faith in lieu of political debate. At worst, this led to abusive and cult-like control of rank-and-file communists, as in the California-based Democratic Workers Party.9 While many disagreements within the NCM were healthy, their means of resolving them tended toward the destructive. Echoes of this persist in the contemporary Left, with younger Marxist-Leninists masking their personal disagreements and personality conflicts in jargon like revisionism and opportunism, and anarchists charging their rivals with authoritarianism. These terms are often played against each other in debate, but the intent behind them is rarely unpacked, preventing either side from identifying the source of their disagreement and learning from it.

Cadre in the NCM were aware of these issues, and in their waning days left a legacy of theory on dealing with them, such as the text Constructive Criticism: A Handbook by the radical therapist Gracie Lyons. Intervening in the culture of the Left, Lyons synthesized Maoist philosophy like On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People and therapeutic techniques like non-violent communication to develop a guide to giving criticism and self-criticism with the aim of helping each other grow and learn, rather than tearing comrades down and treating them like enemies.10

Lyons’s paradigm is that problems among the oppressed and exploited are our collective responsibility. If someone is working inefficiently or spreading harmful ideas, it is incumbent on her comrades to teach her or hold her accountable. If they do so by insulting her or writing her off categorically, she won’t be able to improve, and a thread in the historical party—the bond between her and her comrades, and between the involved parties all of those observing the interaction—will be frayed. On the other hand, if her comrades emphasize unity at all costs and refuse to bring up the issue, they deny her the opportunity to learn, and cause the problem to fester. Rather, we need to be honest and concrete, designing our criticism to help each other learn. All of the best organizers you know got where they are because someone helped them learn from mistakes, and they were humble enough to listen. If we want each strand in the movement to be stronger and reach further, then this is what we sign up for as communists.

These methods don’t just apply to our relationships with each other, but with mass work as well. Every contact you make in the street or the shopfloor is a potential comrade or sympathizer. Most people have an ambiguous relationship to the Left, viewing us through the lens of either Cold War propaganda or world-weary unfamiliarity. If we bring uncomradeliness into mass work, we risk leaving the impression that communists are derisive and chauvinistic, which cuts us off from a potential base. We should work to make it so that when asked about us, those in our base will answer that communists are honest, direct, and genuinely care about the lives of the exploited.

This is why so many organizing guides hit on the necessity of listening. This is sometimes done through the 80/20 rule—that organizers should spend eighty percent of their time listening and twenty percent talking, speaking up only to ask questions, clarify concerns and give concrete tasks. Talking too much tells people that you’re there to sell them something rather than to solve a problem. Listening builds trust over time, which then allows us to bring our politics into play.

Through cultural intervention, we can change how communists relate to each other and the working class. None of our actions in the movement belong exclusively to us, because everything we do has consequences for the collective. Not only can destructive behavior push comrades out of our networks, but it reproduces itself by telling others it’s acceptable to treat each other like enemies and objects. We have a responsibility to set the opposite example for new comrades, teaching them to listen, empathize and practice constructive criticism, and patiently stepping in when someone causes harm. This is how we organize each other, not a specialization we can train select feeling-experts in. We all have to prefigure love-comradeship if we desire to draw masses of people into the historic party and strengthen its resolve against the ruling class.

Starting from intervention among communists and working our way up, we should strive toward a form of cultural revolution—a change in how we relate to each other and our society that rises beyond the left and transforms our entire society, replacing capitalist and settler values with collective ones and opening pathways for new levels of communist organization. The old ways of treating each other serve our enemies, and new ones are required for the construction of socialism.

Among the Enemy

The failure of the communist movement has not occurred in a vacuum, with the blame falling only on ourselves. We operate under conditions of scrutiny and repression, with the state going so far as to infiltrate and surveil study groups and mutual aid collectives. To fight back, radicals use security culture, the cumulative practices and technologies for rooting out and inhibiting the work of state agents, informants and provocateurs, and the process of turning these practices into cultural norms and training new radicals in them. In many movement spaces, veterans zero in on the newly activated and begin passing down elements of security culture, like workers telling new hires about job hazards that management refuses to fix.

Most radical security practices were developed for underground work, from pipeline blockades to anti-fascist streetfights, and reflect the needs of this work: encrypted apps, masks, need-to-know information sharing, unadvertised actions, and organizing within private groups of trusted comrades. None of these methods are foolproof. Informants and undercover police wiggle their way into Signal chats, catch wind of surprise actions, and identify masked militants. The game of cat-and-mouse between the ruling class and the Left is always developing, with no tactic offering absolute safety from state agents who are capable of learning and adapting to our forms of struggle. But for activists engaged in militant direct action, security culture often means the difference between imprisonment and walking free.

Attempts to translate security culture into aboveground base-building and mass politics, however, often create friction between commitment to privacy and discretion and the needs of public, outward-facing work. Organizers radicalized in ambiguously legal protest movements naturally bring the tools they learn to other forms of work, such as economic organizing and study groups, as if encrypted texting is a spell to keep the police at bay rather than a contingent tactic for a specific terrain of struggle. This can look like union organizers convincing uninitiated workers to plan campaigns exclusively on Signal or radicals showing up to quiet vigils with their faces concealed.

Rather than being applied unilaterally, these security practices need to be weighed against any trade-offs in effectiveness. For example, if an elderly tenant interested in getting their sink repaired has trouble learning to use Signal, it may be best to just err on the side of efficiency over precaution and send them an email. Similarly, if a new protester is intimidated by your balaclava, the benefit of earning their trust may outweigh the cost of being photographed at an action. Security practices cannot be applied mechanically, but need to be tailored to the needs of the moment. Dogma, whether political or tactical, hands infiltrators an easy-to-memorize means of blending in, while adaptability and critical thought makes their ingenuousness stand out. Methods developed for underground activity translate unevenly into party-building and mass work, sometimes fitting neatly, sometimes derailing good organizing, and sometimes turning into a useless ritual. Like our enemies in blue, we need to learn and adapt to stay ahead.

While the world of cloak-and-dagger direct action may be alien to those of us immersed in mass work, state repression remains a constant threat. Agents have crashed mergers between parties, severed ties between dear comrades, and created entire collectives as fronts for their activity. A repressive apparatus capable of handling complexity and change requires an equally adaptive response.

While most handbooks on security are meant for the underground, there is a small body of thought on security in public movements, mostly passed down directly from organizer to organizer. The closest thing to a bible of movement security is J Sakai’s Basic Politics of Movement Security, which takes security not as a specialized practice, but as something embedded in how we debate, organize and relate to each other. In his words:

Security is not about being macho vigilantes or being super suspicious or having techniques of this or that. It’s not some spy game. Security is about good politics, that’s why it’s so difficult. And it requires good politics from the movement as a whole. Not from some special body or leadership or commission—from the movement as a whole. This is demanded of us. It’s part of the requirement to be a revolutionary, that you try to work on this.11

When Sakai uses the term good politics, he’s not referring to a certain Marxist doctrine, but to an ability to understand our circumstances and make the correct decisions, whether in mundane practice or grand strategy. In almost every instance of infiltration on public record, the state has taken advantage of the movement’s political failures, leveraging them to gather information or disrupt organizing. This is intimately tied to the cultural interventions discussed in the section above. The primary solution is not to design some special tool for identifying police, but to create resilient organizations that can’t go up in flames because of the ill intent of a minority of members.

In the previous section, we identified two forms of uncomradely behavior—treating comrades like enemies to be torn down and objects to be used. The state is well-aware that we suffer from both of these problems, and have historically used them against us.

Treating comrades like enemies hands the state a tool to sabotage revolutionary movements. Organizations only function when their components work harmoniously toward a common goal. When we engage in political conflict, we need to recognize that our comrades are trying to use different means to achieve the same ends, not to stop us from achieving those ends. Agent provocateurs, who do intend to stop us, almost always stoke bad faith in these disagreements to generate an organizational breakdown.

Racism, sexism and other forms of oppression compound this problem. When these dynamics go unaddressed in the movement, leaders are able to form cliques that exclude the oppressed, denying them status as comrades and equals. Sakai calls this men’s solidarity, where the sense of brotherhood between men allows them to insulate each other from criticism. Sakai’s term is shorthand here: The problem is not specific to men or masculinity. White women and petty-bourgeois intellectuals, for instance, are both capable of creating similar reactionary in-groups that privilege their cultural norms and allow them to defend each other from criticism and change. If you look closely, you will also find similar patterns outside of oppressor-oppressed dynamics, though that’s where you’ll find them most chronically.

Sakai explains the concept using the story of a radical named Tom, who he describes as an aggressive and macho movement leader in Chicago. His politics amount mostly to poor whites building “White Power” in alliance with the Black Power movement. Those who held this vision formed a wing of the Rainbow Coalition built by the Chicago Black Panthers, with whites representing themselves as a distinct national community. While Sakai leaves his last name and organization unspoken, he is implied to be Tom Mosher, a federal informant active in a number of radical organizations during the 1960s and 70s—the group Sakai describes seems to be either Rising Up Angry or the Young Patriots Organization, both based among working-class, white Appalachian migrants in Chicago. This is not a full treatment of the Rainbow Coalition or the Young Patriot Organization’s politics, which were as complex as any mass movement, but the point stands that their most conservative elements became a source of power for the state.

Tom was insulated by a leadership clique of childhood friends, who recognized the issues with his politics and behavior but defended him because of their relationship. A group of white and indigenous women, disturbed by his behavior and believing him to be an informant, called for Tom’s expulsion and mobilized enough support to kick him out. This wasn’t, however, the end of his career in the movement. Tom ingratiated himself with middle-class leaders in Students for a Democratic Society, relying on the same bond of solidarity between men to worm his way back into activist spaces. He moved to California, freely participated in armed revolutionary organizing, and eventually either instigated or carried out the murder of a Black Panther before coming out publicly as an informant and testifying against the Panthers in court.

A similar case forms the basis of Courtney Desiree Morris’s Why Misogynists Make Great Informants. In 2008, the anarchist organizer Brandon Darby revealed himself to be an informant for the FBI, reporting on protesters at the 2008 Republican National Convention. As Morris points out, however, Darby’s career as a provocateur began before he was officially recruited by the FBI. When he began informing, Darby already had a wealth of experience destabilizing movements for his handlers to draw on.12

As a leader in the Common Ground Collective, a disaster relief project in post-Katrina New Orleans, Darby dismissed, insulted and assaulted female volunteers, alienating women from the organization and its work. Common Ground blamed Black men in the surrounding community rather than the white men in its leadership, failing to hold Darby accountable for his actions. As Morris demonstrates, Darby’s comrades would not have had to catch him in the act of calling his handler to prevent him from informing. If they had held him accountable for his destructive behavior, he would not have reached the point where the FBI identified him as a possible asset and brought him into their fold. Instead, his male comrades’ desire to placate him shielded a future informant.

In both of these case studies, agents were able to take advantage of insular, self-reinforcing cliques of male leaders and use them to drive out women and people of color. Cadre were scattered, recruits were alienated, and movements were driven into the ground.

On the other hand, when we treat comrades like objects to be used, we create a different kind of harm. This commonly takes the form of tokenism—creating the illusion of concern for the oppressed by promoting a small number of them into leadership, without addressing their needs dynamically or building a mass base among them. Nonprofits are notorious for doing this by hiring individual women, low-wage workers and people of color as spokespeople while glossing over the complexity and division within those communities. This creates public goodwill by implying that the nonprofit’s positions reflect those of the community, whether that’s accurate or not. The culpability of liberal professionals in tokenism, however, does not mean revolutionaries are immune to it by virtue of our politics.

Like the 80/20 rule described earlier, a run-of-the-mill organizing maxim can help us navigate the weeds of exclusion and tokenism: Leaders should always work to replace themselves with new leaders. Rather than creating a permanent clique that steers a collective for its lifespan, cadres should invest time and energy into bringing those on the periphery into the center, giving them mentoring and encouragement. This concept is deceptively simple, hiding a host of choices organizers must constantly make around who and where to direct their time and attention to. When you have time for a single organizing conversation, who do you choose to have it with? When you need to assign a task, which of your comrades do you ask first? When elections for new leaders are coming up, who do you encourage to run? Who do you treat with suspicion, and who do you choose to trust? All of these questions intersect with class and identity, slowly changing or maintaining the revolutionary Left’s composition. This makes every organizing act fundamentally political, because everything we do impacts who gains the expertise and confidence to step up and take leadership and who does not. This work does not stop when you’ve filled a quota of women or people of color in elected roles; it requires a permanent commitment to building mass leadership among the oppressed.

Infiltrators thrive on both insularity and favoritism. These are two sides of the same coin, allowing them to take advantage of organizations that pivot too far in either direction. The self-replacement of leaders is not holy water that casts them out, but dispersing cliques and planning for cadres to regularly turn over leadership turns the state’s work surveilling and sabotaging the Left into a long war of attrition.

Security is woven into every part of how we organize. Whether we know it or not, we’re constantly engaging with state agents trying to disrupt our work. Copjacketing, when one accuses a comrade of being an agent without hard evidence, only gives them another weapon to breed distrust and dysfunction. The most powerful defense against disruption is to build organizations that can’t be derailed by bad actors, tearing up the parts of our culture that the state most easily uses to its advantage and replacing them with tight relationships, clear politics, and democratic practice.

A Home for Communists

In the coming years, our aim should be to build a welcoming home to revolutionary communists who, like us, reject the sectarianism of dead generations, but who share our commitment to internationalism, democracy, and rooting in the working class. We walk a delicate line between the unity needed to coordinate our struggles, and the autonomy necessary to adapt to local conditions and experiment with new methods. Our activity will determine the durability of this home. Reproducing the logic of purification and scorched-earth debate will create a party where these are commonplace and acceptable practices. Setting a standard for conduct, and building widespread relationships now will help us create an open and lively formal party with a culture of constructive disagreement.

As we learn how to party-build, we will need to answer some questions along the way. First, where do we draw our line in the sand? What are the outer limits of unity between communists, and what common politics bring us together? Sectarians make the mistake of using almost everything as a litmus test for unity: if we can’t agree on the correct interpretation of dialectical materialism, the class character of the Soviet Union, the moral high-ground in any given geopolitical conflict, our exact relationship to the labor movement, or whether to run food distribution programs, we do not belong in a shared party. Sectarians have a shared affinity around a solitary tendency, a single answer to tactical questions that functionally limits their bonds with the working-class and the rest of the Left. Rather, we must seek harmony between tendencies that share a commitment to socialism, revolution, and working-class internationalism. Sectarian logic leads to constant splits and purges, which has left us with a dizzying array of uncoordinated sects. While disparate sects are sometimes able to form coalitions to pursue common aims, coordinating and communicating becomes a more complex process each time we multiply, exponentially increasing the energy required to challenge capital.

On the other hand, DSA officially draw their line around anyone who identifies as a socialist and agrees to pay dues. While DSA is not apolitical, chapters tend to focus on single-issue campaigns and rarely determine common strategic vision. DSA struggles to articulate its own purpose and push its network of chapters and committees to fulfill it, despite having many movement veterans amongst its ranks. Compounding this, politicians affiliated with DSA have no loyalty to priorities set by the membership. For instance, Congressman Jamaal Bowman drew fire from a large section of DSA’s rank-and-file and its BDS Working Group for supporting US funding for Iron Dome, an air defense system used by Israel to slaughter Palestinians.13 While dozens of DSA chapters across the country published calls pushing to discipline or expel Bowman for violating their commitment to international solidarity, Bowman remained unmoved and DSA’s National Political Committee refused to censure him.14 While socialists move in one direction, their representatives move against them.

Many of us standing between these poles, including those clustered until recently in Marxist Center, have answered that we are for base-building, forming direct relationships with working-class people and helping them build their own structures for combating their class enemies.15 As comrades Jean Allen and Teresa Kalisz identify in their dossier From Tide to Wave, however, “the apolitical trend in base-building now threatens to make what socialists and communists are building a base for left progressives rather than a revolutionary working class movement.”16

The practice of base-building taken on its own is easily co-opted by social reformers, using class struggle unionism and direct action to build a base for the Democratic Party and its machinery, not unlike the relationship between communists and the CIO labor bureaucracy in the 1930s and 40s. Even fascists engage in mass work, disseminating resources and organizing their chosen base. At the precipice of base-building, we again face the question of political unity. In order to make our own mass work distinct and ensure that it works to our ends, we need to develop a political program of our own. When cadres are sent to practice mass work for their own sake without a higher sense of purpose, lines of communication often weaken and their motivation for engaging in base-building becomes unclear, leading to pessimism and burnout. Political vision is an organizing tool, giving cadres a sense of meaning that incites them to work harder and not give up, whether they’re tasked with investigating a site of struggle, canvassing a base, or leading a protest. Our challenge will be to answer the strategic questions facing the communist movement without getting lost in sectarian squabbles about long-since collapsed states and hypothetical modes of production.

Secondly, we will need to experiment with different forms of organization to determine which best facilitates our needs. The Left often traps itself in a noxious debate about centralization vs decentralization, with one extreme arguing for a tightly-knit party operating as a single unit and the other for loose networks or a constellation of discrete organizations.

Dogmatic centralization leads to decisions being made by those with no context for them, dictating the struggle from afar, whether democratically as a mass membership or bureaucratically as a central committee. The Chinese Communists learned this lesson bitterly when the Communist International pushed them to retain unity with the nationalist Guomindang, even when the Guomindang butchered them and drove them into the deep countryside after they’d outlived their usefulness. The Comintern, isolated thousands of miles from the struggle itself, still believed that the Chinese Communist Party should pursue national revolution based on the nascent bourgeoisie and urban-working class, while the majority of the party was cut off from the working-class and surrounded by a blooming movement of poor peasants. Chinese cadres on the ground had to forge their own path, counter to Moscow’s orders.17 Dogmatic centralism can also result in shell organizations, where visionary leaders craft what they feel is the perfect party-form and draft ornate political lines, but fail to build the relationships necessary to fuse them with the historical party—sects waiting eternally for the masses to fill their halls.

Decentralization, on the other hand, leads to inertia and confusion. Without a common purpose and strategy, communists will not have the cohesion to contest an organized capitalist state and build socialism. This same issue arises at different scales, from the neighborhood to the world-system. Many of us know it in the form of local struggles that fail when a corporation relocates a store to evade unionization or when a national landlord shrugs off a rent strike in a single building. On a larger scale, we face the capitalist world-economy choking out isolated socialist states. We need to cohere the historical party into something greater or it will die in the neighborhood, the sector, and the nation.

While we can’t go back and repair the relationship between Yan’an and Moscow, we can begin to study how contemporary parties can adapt to the needs of their locals, and locals to the needs of their cadre, all while working toward the same ends. Rather than becoming dogmatists for centralism or horizontalism, we should pick up where past organizations left off and study both scientifically, using what we find to guide the process of party-building. The collectives within the historic party can serve as a laboratory for exploring and debating these questions, even while we move closer to regrouping and consolidating theories that hold up to practice.

This piece is not a substitute for the development it calls for. Cultural intervention allows us to build sustainable networks, providing a platform for communists to stand on without being dragged into infighting and provocation. We have difficult work ahead of us codifying ideas into strategy and relationships into structure. It can be difficult to imagine that our love for each other and for the exploited can become something more expansive. The exchange between the choices we make and the evolving conditions of capitalism, however, will determine the course of the entire movement. Our current ability to mediate conflict and make decisions among ourselves is an indicator of our future ability to do so as we expand and develop.

As Marxists we must understand that liberation comes from the revolutionary potential of the entire class—the ordinary people whose labor created the food we eat and the homes we live in, who deliver newborn children and wash piles of dishes, and who hustle from gig to gig to survive—not some outside force that will save us if we make the right calculation or appease the right politician. The working class has always been heterogeneous and contradictory, with a complicated relationship between its universal interests and those of its particular fractions. Unity is grounded in diversity, requiring communists to mediate contradictions within the class and bring its entirety onto the side of the most exploited and oppressed.

My hope is that we take the challenges I have outlined as an invitation for the entire movement to find common politics in the form of a program, and space for collaboration in the form of a party, and to take seriously that every action we take is part of their construction. Building the party doesn’t just consist of the official proclamations of a handful of spokesmen, but of the aggregation of steps toward harmony and coherence all of us make. A comrade in Marxist Center, echoing Gracie Lyons decades before, put it best: “when making any political decision, our primary question should not be what is best for ourselves or best for our organization, but what is best for the movement as a whole.”

This work was the result of a process of discussion, revision and synthesis with more comrades than we have room to name here. All of them have some claim to authorship of this piece. Specific thanks go to Jenny, Jean, Jess, Rudy and Amelia, for their diligence and inspiration, and to Josh and Veronica for the past three years of collaboration.

- Parsons, Lucy. “I’ll Be Damned If I Go Back to Work Under Those Conditions!” The Anarchist Library. Accessed January 25, 2022. https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/lucy-e-parsons-i-ll-be-damned-if-i-go-back-to-work-under-those-conditions.

- Brecht, Bertolt. The Solution. The Collected Poems of Bertolt Brecht. Translated by David Constantine and Tom Kuhn.

- Marx To Ferdinand Freiligrath, February 29, 1860, Marxists Internet Archive. https://marxists.architexturez.net/archive/marx/works/1860/letters/60_02_29.htm

- Bordiga, A. 1965. When the Party’s General Situation is Historically Unfavorable. Marxists Internet Archive. https://www.marxists.org/archive/bordiga/works/1965/consider.htm

- Elbaum, M. (2018). Revolution in the air sixties radicals turn to Lenin, Mao and Che. Verso.

- Townsend, C. (2020, July 27). Letter to the Socialists, Old and New. Regeneration Magazine. https://regenerationmag.org/letter-to-the-socialists-old-and-new/

- Dean, J. (2019). Comrade: an essay on political belonging. Verso.

- Kollontai, A. (1923). Make way for Winged Eros: A Letter to Working Youth. Marxists Internet Archive. https://www.marxists.org/archive/kollonta/1923/winged-eros.htm.

- Breslauer, G. (2020, December 30). Cults of our Hegemony: An Inventory of Left-Wing Cults. Cosmonaut. https://cosmonautmag.com/2020/11/cults-of-our-hegemony-an-inventory-of-left-wing-cults/

- Lyons, G. (n.d.). Constructive Criticism: A Handbook. https://www.marxists.org/history/erol/ncm-3/constructive-criticism.html.

- Sakai, J., & Hiscocks, M. (2014). Basic politics of movement security: a talk on security with J. Sakai, May 2013 ; & G20 repression & infiltration in Toronto–an interview with Mandy Hiscocks reprinted from Upping the Anti #14. Kersplebedeb.

- Morris, C. D. (2010, May 30). Why Misogynists Make Great Informants. Truthout. https://truthout.org/articles/why-misogynists-make-great-informants/.

- “DSA BDS and Palestine Solidarity Working Group Formally Calls for the Expulsion of Rep. Jamaal Bowman.” Democratic Socialists of America BDS and Palestine Solidarity Working Group. Accessed January 21, 2022. https://palestine.dsausa.org/dsa-bds-and-palestine-solidarity-working-group-formally-calls-for-the-expulsion-of-rep-jamaal-bowman/.

- December 2, 2021. “On the Question of Expelling Congressman Bowman.” Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), December 3, 2021. https://www.dsausa.org/statements/on-the-question-of-expelling-rep-bowman/.

- Horras, T. (2019, March 26). Base-Building: Activist Networking or Organizing the Unorganized? Regeneration Magazine. https://regenerationmag.org/base-building-activist-networking-or-organizing-the-unorganized/

- Kalisz, Teresa, and Jean Allen. “From Tide to Wave.” The Left Wind, March 14, 2021. https://theleftwind.org/2021/03/14/from-tide-to-wave/.

- Meisner, M. (1986). Mao’s China and after: a history of the People’s Republic. The Free Press.