Translation and introduction by Alexander Gallus.

The reputation and legacy of cybernetics throughout the history of so-called AES/state socialist countries was fraught with controversy. The following study by Jérôme Segal not only shines a light on the varying official communist treatment and evolution of cybernetics itself, but gives a glimpse into a past world, into what some may consider an eccentric history; however, despite varying political estimations of the problems of AES in East Germany and elsewhere, this history genuinely raises or should raise questions for socialists in the 21st century. As Rainer Thiel, collaborator with the famous East German cyberneticist Georg Klaus, said in an interview with Neues Deutschland last year, it was only after they published an article in the official SED (Socialist Unity Party) science journal Einheit that they made some progress with the popularization of cybernetics in East Germany.1

This was in large part due to the cover by and support of Socialist Unity Party Chairman Walter Ulbricht. When Ulbricht faded from the spotlight, so did the establishment of cybernetics as a burgeoning concept in the construction of socialism. As the Allende government in Chile was experimenting with Cybersyn, the new SED Chairman Erich Honecker in 1971 wrote off cybernetics and systems research as “pseudoscience”. Despite the inherent forward-looking character of the Marxist doctrine and its focus on the need to develop the productive forces of labor and efficient planning, the world’s historic socialist states failed to keep up with and outdo the West economically and politically.

The tragic examples of Victor Glushkov’s repeated failed attempts to implement a proto-internet in the USSR also are striking. While reservations about the costs of the proposed plans could be considered understandable arguments against these proposals in the early 60s, given the backward challenges still facing the Soviet Union at the time (in food production, vital consumer items, geographic inequalities, etc.), a commitment to cybernetics would clearly have positively aided the Soviet Union’s et. al. economic and social ails in the long term. The fact is that the Soviet Union’s Cold War adversary, the United States, was more forward-looking in this respect and indeed went on to create the internet, whereas the Brezhnev government watered down and denied proposal after proposal.

Many prominent socialists in the 20th century, such as Che Guevara, Salvador Allende, and Khrushchev himself, were preoccupied with studying Western productive technologies and scientific achievements, and deeply worried about the technological backwardness of the international socialist camp. While East Germany engendered a strong academy and clearly permitted irregular independent intellectual investigation, the changes in the late 60s and 70s tended to stifle precisely the innovative research necessary for socialism to outcompete capitalism on the economic and political plane. As Segal suggests, it is impossible to talk about the German Democratic Republic without mentioning the parallel or often preceding occurrences and debates in its “brother country,” the USSR.

The premature stifling and quelling of the cybernetic efforts in East Germany therefore cannot be separated from the reestablishment of the more conservative, philistine bureaucracy in the Soviet Union in 1964 and the country’s gradual disintegration. Whereas cybernetics is certainly not a replacement for Marxism or the need for political representation, cybernetics clearly offers fruitful possibilities for democratic engagement and coordination, especially as it pertains to economic planning. As a brief introduction to the general development of cybernetics and its unique appearance in East Germany, this study will hopefully shed some light on the understudied practical history of cybernetics and stir debate on its future applications.

The Introduction of Cybernetics in the GDR by Jérôme Segal

Summary

Until the end of the 1950s, a young scientific theory was labeled ‘bourgeois’ and ‘pseudo-science’ and even defamed as a ‘plague’ in the Eastern Bloc. This was the general theory of control and communication known as cybernetics; Nikita Khrushchev and Walter Ulbricht positively referred to cybernetics at their respective party congresses in 1961 and 1963. In these two speeches, cybernetics appeared as a science to be promoted.

A historical study, first on the context of the emergence of cybernetics, but especially on its development and its implementation in the GDR, will allow us to find explanations for this astonishing interest of politics in a ‘mere scientific theory’. The analysis of the controversies connected with the introduction of cybernetics in the GDR, reconstructed on the basis of journals, documents from various archives, as well as interviews with contemporary witnesses, will bring many aspects of the history of the GDR into play: the actual history of science as well as the political and economic history of the country. Finally, the examination of various biographies, such as that of Georg Klaus (1912-1974), who was instrumental in introducing this theory to his country, will provide us with further insights into this connection between science and ideology.

On the context of the study

At the end of the 1940s, a natural science discipline emerged in the United States that quickly found various applications in many individual sciences. This discipline – although the term ‘discipline’ is undoubtedly inaccurate and rather misleading – soon became known as ‘cybernetics’. Starting from a mathematically defined concept of information, this general theory of regulation, control, and communication has substantially stimulated new approaches to a unity of knowledge whose history has not yet been written.

An accurate analysis of scientific papers as well as of archival documents will allow us to show which are the mathematical, physical, and technical origins of the concept of information and from there to lead to a better understanding of the importance that our today’s so-called communication society or ‘cybersociety’ attaches to information. The aim here, then, will be to look from a new angle at the respective relationships between mathematics, physics, and engineering, to determine the role of the engineer in the forties, and, consequently, to illuminate the interrelationships between science and society.

Connections between science and ideology are constitutive for the historical development examined here from the very beginning, not least because cybernetics and information theory in their context of origin is closely connected with decisive technical developments brought about by war research. A theory which, like information theory, has ‘conquered’ several other parts of knowledge, can be placed in a network of various scientific influences, basing it on a material structure that is linked to the organization of science itself as well as to political decisions concerning it, and in this respect belongs to the foundation of society.

Likewise, the history of the Internet – which as an application of the cybernetic way of thinking also finds its place in this ‘archaeology’ of the concept of information – could equally be treated as an encounter with an ideology. If we are concerned here with the introduction of cybernetics in the GDR, then simply for the reason – to continue with Foucault – that the different conditions of possibility of discourse in a highly centralized state can be better understood. Moreover, due to the dictatorial aspect of its political system, one finds in the GDR the explicit will to bring the cybernetic foundations to all-encompassing applications in the country. The investigation of various scientific institutions as well as the systematic evaluation of some scientific journals, in which the controversies addressed by the interviewed time witnesses found their expression, allows for an account of the history of cybernetics’ reception in the GDR, in which, on the one hand, the history of science is considered in connection with political, economic and institutional history, and which, on the other hand, can be regarded as representative for a general history of cybernetics and information theory. The history of the introduction of cybernetics in the GDR should then rather be seen as a case study within this broader investigation.

However, the primary concern here is the historical reception of a scientific theory. First, the origins of cybernetics and the circumstances of its emergence will have to be presented, before its introduction in the GDR can be distinguished into three phases: first, the ‘infection’ of the Eastern Bloc by a supposedly bourgeois science (1948-1961), then the establishment of cybernetics in its official interpretation as a scientific confirmation of dialectical materialism (1961-1963), and finally the period of degeneration and normalization (1963-1971).

1. Context of development of cybernetics and information theory

In order to better understand which aspects of cybernetics were adopted by East German scientists, but also to show to what extent cybernetics was already ideologically influenced at the beginning, it is unavoidable to give a brief outline of its genesis. “The deciding factor in this new step was the war”, as the mathematician Norbert Wiener, the founding father of cybernetics in the United States, put it succinctly in his emblematic book Cybernetics, which gave the new theory its name. Wiener was referring with this significant statement to his 1940/41 research on the improvement of air defense systems, which he had already begun before the Americans entered the war. The founder of communications theory was also active in wartime research at the same time: Claude Shannon (born 1916) was working on cryptology problems in a working group of the National Defense Research Committee. In 1945 he wrote down the results of his research in “A mathematical theory of cryptography”. The work remained classified for twelve years, but already contained all the elements of the communication theory that Shannon was to publish in 1948.

But this is not only about personal history. Cybernetics also came about thanks to a crucial constellation of research institutions, foundations, and government institutions. For example, the ten ‘Macy Conferences’ (after the foundation of the same name) starting in 1946 provided an opportunity to jointly address various theoretical and technical advances simultaneously under the programmatic title “The Feedback Mechanisms and Circular Causal Systems in Biology and the Social Sciences.” We need only mention the prediction theory in the field of mathematics, the neuron model of Pitts and McCulloch in the field of biology, but also the theories of the sociologists Bateson and Mead, which also contributed to the development of cybernetics as conference topics from the very beginning.

Two significant writings emerge from this context: Norbert Wiener’s Cybernetics, mentioned earlier, and Claude Shannon’s A Mathematical Theory of Communication. A detailed account of these works will not be undertaken here, and the interested reader is referred only to the works of Dupuy, Hagemeyer, Heims, Galison, and Edwards. As a brief and simplifying summary, it must suffice that Wiener primarily makes general considerations about control processes and introduces the model of feedback, while Shannon, in addition to a quantitative version of the concept of information related to entropy, proposes the following general scheme of communication:

No sooner had Shannon’s article appeared in two issues of the Bell System Technical Journal than it was followed by a new edition in book form, this time under the title “The mathematical Theory of Communication”. His reception in the scientific community was emphatic, especially because of the use of terms like ‘entropy’ or ‘cybernetics’. In terms of its relation to technology, the theory presented stands at a mediating level between basic research and application. As a means of justifying a new disciplinary field as well as a mere instrument of thought – with all its political implications – cybernetics undoubtedly also signifies a break in the history of technology in the continuity of the development of various control processes (starting, for example, with windmill construction in the second half of the eighteenth century, patents granted for it at the end of the 1780s, or centrifugal governors for steam engines). In this respect, cybernetics also originates from the various crafts and industries with their diverse automation techniques, which it, however, leaves behind as mere techniques to the extent that it develops itself much more according to the model of a ‘Big Science’.

As a general theory, cybernetics has thus already been linked to political decisions since the end of the 1940s. The communication theory, originally presented in the form of a mathematical theory, is now classified as a sub-science of cybernetics under the name of information theory.

2. Cybernetics infects the East (1948-1961)

The first instance of cybernetics in the GDR that can be traced is the translation and publication of an article under the title “Cybernetics – a new ‘science’ of the obscurants”, which had first appeared in the USSR a month earlier in April 1952. First, then, will be considered the introduction of this theory in the ‘brother country’.

Cybernetics in the USSR

Was there no theory analogous to cybernetics in the USSR? In this framework, we can refer to Kovalenkov’s report from the beginning of 1946. There it is about a clear decision for the automation of industry within the five-year plan of 1946-1950. However, a general plan is only a plan and clearly distinguishable from a general theory. In a report for the Marxist French newspaper Les Lettres françaises, J. Bergier remarked on this plan:

“The automation of the industries of a large country according to an ordered, preconceived, rational plan and within the framework of a general program of reconstruction, thus requires a connection between pure science and practical technology as has never been made before.”

The need for a general theory was thus obviously present, as can be seen, moreover, already in Hermann Schmidt’s work of 1941. In any case, despite the lack of a general theory, significant contributions were made in the USSR in the field of automatic control, such as in the Institute of Automation and Remote Control of the Academy of Sciences. At the SHOT Conference last summer, C. Bissel, in his presentation on “Aleksandr Andronov and the development of the Soviet School of post-war control engineering,” underscored the importance of this institution for theoretical research. He also explained how already in 1941 this institute was sometimes reviled as a place of ‘bourgeois science’, mainly because of the new methods used there (non-causal models etc.), which exposed the researchers working there to the suspicion of scientific idealism.

It was in this context that Soviet scientists became aware of U.S. cybernetics. S. Gerovitch reported at the above-mentioned conference about the campaign waged in the USSR against cybernetics. Apparently, there was an explicit political will to systematically criticize theories judged to be ‘imperialistic’ and, if necessary, even to found a separate institute for this purpose. Then, from 1952 on, a series of articles appeared in humanities journals calling cybernetics an obscure or pseudo-science, the first of which was Yaroshevsky’s essay mentioned above and translated into German. The reasons for this more than reserved attitude vary. After evaluating these papers directed against cybernetics as well as other Marxist journals of the fifties, three main types of explanations for the basic anti-cybernetic attitude in the Soviet Union can be distinguished:

First and foremost, cybernetics was a theory that had originated in the United States and thus had to be regarded as worthy of condemnation almost from the outset in these times of the Cold War. The automation associated with it was too reminiscent of various aspects of Taylorism and appeared as a contrast to its Soviet model, which was supposed to serve the liberation of the workers in order to enable them to work creatively. Moreover, in this context, a definition of labor based on the concept of information would have at least relativized the importance of class relations and clashed with the Soviet variant of Marxism.

Second, cybernetics contained basic philosophical assumptions, first of all, its idealistic interpretation and the enormous use of thinking in analogies, which seemed incompatible with dialectical materialism. The very fact that Wiener had declared that he was equally interested in living beings and machines made him appear in the eyes of Marxist thinkers as a mechanistic materialist at best, which was itself already a revisionist attitude. Moreover, the environment surrounding the system under investigation was assumed to be indeterministic; stability was to be ensured solely by the sensible establishment of regulatory systems. Indeterminism, however, was completely incompatible with the prevailing classical Marxism. It should be recalled here only that at the same time Einstein’s theories of relativity were still in doubt and the French Marxist weekly Les Lettres françaises on June 18, 1953 devoted its front page to Louis de Broglie’s ‘conversion’ from indeterminism to determinism in atomic physics. Wiener’s statement, “Information is information, neither matter nor energy. No materialism which does not take this into account can survive the present day”, proved to be another ‘thorn’ in the flesh of the Marxists.

Finally, the adoption of cybernetic ways of thinking in various individual disciplines gave rise to fears of danger: In economics, cybernetics with its self-control models could justify capitalism, just as the latter was vulgarized in principles such as “supply and demand form the market.” Already in 1952 the Scientific American had presented the Keynesian model of the economy in this way in the form of a cybernetic scheme and thus also justified it. In biology, cybernetics was directed against Pavlov’s reflex theory, which did not provide for feedback. It would be best, it was the view of some scientists, that cybernetics was only a technique and should remain only a technique.

Nevertheless, the Communist Party of the USSR does not seem to have been directly committed against cybernetics. The army leaders of the anti-cybernetic campaign were predominantly humanists. The spectrum of journals in which the campaign was carried out confirms this impression (for example, one cannot find an article on cybernetics in Pravda). In the first half of the fifties, a gap can be observed between political and philosophical positions taken and the actual work of natural scientists. The latter, in fact, were able to work unhindered on cybernetic issues, and often on the basis of Shannon’s mathematical theory of communication, provided only that they did not use the word. By the way, in 1953 Shannon’s publications were translated into Russian and published, but under the title “The Statistical Theory of Transmission of Electrical Signals”. The translators succeeded in the masterpiece to get along completely without the use of the terms ‘information’, ‘entropy’ and even ‘mathematical’.

On the other hand, cybernetics continued to be defamed in the humanities. Thus, the Little Handbook of Philosophy, widely distributed in the USSR, contained a very disparaging article on cybernetics until 1955, but it was not included in subsequent editions.

After 1954/55, the eminent mathematicians A. Kolmogorov and A. Khintchnin – from a strictly scientific approach and far from any applicability outside the so-called exact sciences – dealt with information theory as a part of probability theory. In 1956 Kolmogorov was given the opportunity of a research stay at MIT. Khinchin’s two essays, published in 1953 and 1956, were translated and both published in the U.S. and the GDR in 1957. The rehabilitation of cybernetics was thus completed.

Again, three reasons can be given for this: First, as a result of his critical statements about American society, especially in the second edition of The Human Use of Human Beings, in which he takes a very clear stand against McCarthyism, Wiener was no longer considered an ‘imperialist scientist’. He had acknowledged the importance of Kolmogorov’s work, showed reservations about the educational system of the United States, and was strongly committed against nuclear weapons. He wanted to use cybernetics to develop new prostheses and methods for automatic translation and was more than ever a great friend of the Marxist geneticist J.B.S. Haldane.

Furthermore, the military had also recognized the importance of cybernetics. Gerovich recalls the secret report on cybernetics written by engineer and Vice Admiral Aksel Berg. For the public, it was unquestionably Arnost Kolman’s lecture “What is cybernetics ?”, which he delivered on 19.11.1954 before the Academy of Social Sciences of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR, that indicated the reorientation. It meant a green light for cybernetics. Kolman’s lecture appeared a few months later in the GDR, then also in the French Marxist journal La Pensée, and also in Behavioral Science in the United States.

In an essay published in 1966, M.A. Arbib gives a brief outline of the introduction of cybernetics in the USSR. At this point only the first publication for a broader public from the pen of I.A. Poletaev shall be mentioned, even if it was still discreetly published in 1958 under the title Signal. The German translation was then to be titled ‘Kybernetik’ in 1962. As H. Kindler reports, after that book, cybernetics “sprouted like mushrooms from the ground” – like mushrooms, one is inclined to note, which had already missed several autumns. What was it like in the GDR?

In the GDR

The history of cybernetics in the GDR, as it is revealed by the evaluation of archival documents, journals, and conversations with contemporary witnesses, cannot be schematized with simple causal relationships. If the initial rejection of cybernetics was also based on the exact model of Soviet scientists, its gradual introduction, on the other hand, took place under various influences, Soviet ones on the one hand, such as the publication of Kolman’s lecture, but on the other hand also through reviews of Western works. Furthermore, a change can be observed on the level of journals. From 1958 on, there are hardly any Soviet contributions, while East German scientists publish essays on cybernetics in journals like Einheit, published by the Central Committee of the SED, and especially in the monthly Deutsche Zeitschrift für Philosophie (almost 90 titles between 1960 and 1971).

Thus, the first mention of cybernetics found in this journal is in a review by Hans Fortner of the book Les machines à penser by L. Couffignal. In it, Fortner refers to “a field that in some countries is considered a special branch of science – ‘cybernetics.'” East Germans did not read Soviet literature exclusively! For example, as K.D. Wüstneck reports, it was quite possible for a staff member at institutes of the Academy of Sciences to get hold of Western literature, even if this, of course, often had to be procured with expensive foreign currency.

According to all contemporary witnesses interviewed so far, it is a philosopher who played the main role in the introduction of cybernetics in the GDR: Georg Klaus (1912-1974). To describe his rich biography in detail here would go beyond the scope of this article, so it is briefly summarized in the appendix, and only key points of his life related to his commitment to cybernetic theory will be recounted here. Growing up in a rather poor milieu (his father was a railroad worker, his mother a housewife), Klaus received special support from the city of Nuremberg because of his extraordinary school achievements. His studies of mathematics at the University of Erlangen, which he began in 1932, were interrupted after only three semesters when the National Socialists arrested him for “illegal district leadership of the Communist Party in Northern Bavaria”. After spending time in various prisons, he was deported to Dachau, where – just like in Stefan Zweig’s chess novella – he managed to keep his wits about him thanks to blindfold chess games. His interest in formal logic – incidentally, another former “bourgeois” science – seems to stem from this.

Klaus continued his political activities after the war and earned a doctorate in 1948 with a dissertation on “The Epistemological Isomorphism Relation” at the Friedrich Schiller University in Jena. After his habilitation in philosophy, he first became professor and dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences in Jena, then in 1953, he followed the appointment to the chair of logic and epistemology at the Humboldt University in Berlin [GDR]. It is worth mentioning that Klaus is one of the few important chair holders who had not previously been in the Soviet Union, nor was he even proficient in Russian. Nevertheless, it will be he who will publish Kolman’s speech in the Forum. However, one of his two closest collaborators, Rainer Thiel (b. 1930), suspects that Klaus, who was fluent in English and French, as evidenced by his notes on Ashby’s book, may have obtained Wiener’s Cybernetics as early as 1952. The appearance of Kolman’s paper finally, H. Drieschel was to recall in 1963, “broke the ice.”

The first East German contribution of his own to cybernetics was a lecture given by Klaus in 1957 and published as a book in the same year under the title: Electronic Brain against Human Brain? – On the Philosophical and Social Problems of Cybernetics. Heinz Liebscher, the second of Klaus’ doctoral students, remarks that his lecture at the second congress of the “Society for the Dissemination of Scientific Knowledge” had given Klaus the opportunity to speak out emphatically “against a mechanical-materialistic vulgarization of cybernetics as well as against a pseudo-dialectical-materialistic rejection”. Cybernetics is presented in this lecture as a theory for the new calculating machines, and in its importance is compared, following Kolman’s account, with atomic energy.

An essential milestone for the introduction of cybernetics in the GDR was the first publication on this subject in 1958, in the unit closely connected with the political rulers, after whose appearance cybernetics could already be considered officially recognized. Klaus developed in his essay “On some problems of cybernetics” a real strategy to persuade the ‘comrades’. Only after seven pages on Marx and the situation of the Soviet Union does the word ‘cybernetics’ appear in the context of the question of whether machines can think or not. He reminds us that without the ENIAC it would have been impossible for the Americans to develop the atomic bomb. Of course, his examples are not chosen at random when he cites different computing facilities and compares their performances: ENIAC 250 multiplications per second, BESK in Stockholm 3 000 and finally BESM in Moscow 8 000! Moreover, he uses the Sputnik effect before turning to cybernetics: No Sputnik without ‘computing machines’! Klaus goes on to say that these new machines are a special feature of the current scientific-technical revolution, as it is currently underway in the East. As far as the expression ‘thinking machine’ is concerned, there would be, as he explains, in this context “a new mathematical theory, the so-called information theory”. Even a representation of Shannon’s scheme of communication, but without interference, is offered to the reader, and Klaus adds: “The information theory now shows that one can grasp the concept of information content mathematically. And here there is a surprising analogy to thermodynamics. The information content is formally a negative entropy. “Here we find the information-theoretical approach of a Kolmogorov or a Khinchin to cybernetics. Finally, in the third part of his essay, Klaus states, “The analogy between man, animals and machines leads to the emergence of the concept of cybernetics. “

In any case, a single article in Einheit was not enough to break all resistance to cybernetics legitimize it. Subsequently, there were still fierce objections against the new theory, raised mainly by other philosophers, but also by natural scientists who, for their part, did not want to get involved in these philosophical quarrels, and who, moreover, feared a softening of the already firmly institutionalized disciplinary boundaries and were hostile to interdisciplinary work. For example, famous natural scientists such as the physicist Rompe or the biologist Rapoport spoke out against cybernetics in the Academy. Rainer Thiel, remembering this time, assumes today that the East German scientists were not yet ready for such a paradigm shift in the Kuhnian sense, caused by a transdisciplinary theory like cybernetics.

3. Controversies in the GDR about cybernetics? (1961-62)

Why the question mark? Although there were debates and conflicts between institutions or scientists, they found only very little expression in journals and monographs. From the moment it became clear that cybernetics enjoyed official support, only a few scientists remained who still dared to question it. In addition, personal quarrels became increasingly evident in these disputes. The philosopher Hermann Ley, for example, opposed cybernetics as an irreconcilable opponent of Klaus. In any case, five different explanatory approaches can be distinguished in this gradual acceptance of cybernetic theories: the role of Khrushchev, the contributions made by Klaus, the political situation, the importance of foreign literature, and finally the practical technical successes more or less tied to cybernetics.

Already in the context of automation, Khrushchev had urgently called for its application in industry at the 20th Party Congress in 1956 and, moreover, had established an ‘Automation Ministry’ for this purpose. Cybernetics was then explicitly mentioned at the 22nd Party Congress in 1961:

“The transition to the most perfect automatic control systems will accelerate. Cybernetics, electronic calculating machines and control systems will be widely applied to production processes in industry, construction and transportation, research, planning, projecting and designing in accounting and administration.”

One month later, at the 14th Plenum of the Central Committee of the SED, these words of Khrushchev were immediately applied in the GDR. On the agenda now is the conception of science as an instrument for improving production and especially productivity. In reviewing the goals of the Seven-Year Plan 1959-1965, cybernetics takes a front seat.

Again, although the GDR’s science policy was partly determined by events in the Soviet Union, it nevertheless possessed a momentum of its own that could not be overlooked. As early as April 1961, Klaus had organized a “scientific consultation” of the journal Einheit on the topic of “cybernetics, philosophy, and society”. In his report of this meeting, which brought together more than 30 scientists from a wide variety of disciplines, Rainer Thiel qualified its effect as a “break” in the history of cybernetics in the GDR. The first significant East German work on cybernetics then appeared in the same year, 1961; it was Die Kybernetik in Philosophischer Sicht (Cybernetics from a Philosophical Perspective) by Georg Klaus. After two years as head of the philosophy working group at the Academy of Sciences, Klaus had also been accepted as a full member of the Academy that year. In his book he does not only know how to prove the compatibility of cybernetics with dialectical materialism, but even more it serves him to confirm it. An article published on October 15, 1960 in Neues Deutschland (The daily newspaper of the party) under the factual title “Control loops and Organisms” had already contained a paragraph entitled “Bestätigung des dialektischen Materialismus” (confirmation of dialectical materialism). Nevertheless, another paragraph of the same article was devoted to the proof that robots could not think dialectically. Cybernetics serves philosophy, but is by no means capable of replacing it. What happens here is a re-appropriation of cybernetics by Marxist philosophy, the scope of which undoubtedly justifies the following summary.

In the best accordance with political correctness, as one would say today, Klaus first shows how deeply the notion of control is rooted in dialectical materialism. Thus, in the German Ideology (1848), Marx and Engels call upon the proletariat to appropriate the means of production, thereby achieving ” self-actuation.” Klaus ends by proposing a series of relations of equality: between the control loop and dialectical unity, feedback and the dialectical relation between cause and consequence, and between information and the special relations that unite matter and consciousness. Furthermore, he distinguishes four aspects in cybernetics: regulations, systems, information, and game theory, not hesitating, by the way, to expound how this last aspect allows one to theoretically simulate the class struggle.

From a methodological point of view, cybernetics extends and deepens dialectical materialism by means of the black-box method, cybernetic analogy, “mathematical imitation of dialectical contradictions” and the trial-and-error method. Finally, cybernetics and Marxism-Leninism appear to be so closely related that the view emerges that the “bourgeois” cyberneticist developed dialectical materialism without knowing it.

Marxist theory is enriched by these writings. Thus, in 1969, a West German Marxist devoted an entire book to Marx’s theory of reflection in its relation to cybernetics. Klaus himself introduces the concept of function and structure in place of the classical opposition between matter and energy. Within this framework, he also proposes a cybernetic and progressive interpretation of democratic centralism, in which he not only implicitly casts doubt on the leading role of the party, but furthermore views the party as a learning system.

The question of determinism and indeterminism is also given a new interpretation by cybernetics, which shows that the control circuits guarantee the stability of the system despite “noise” and external disturbances, thus confirming the determinism underlying dialectical materialism. As late as 1976, a dissertation entitled Dialectics and Cybernetics in the GDR was devoted to the work of Georg Klaus.

These theoretical researches, based on a cybernetic interpretation of Marxism as well as on a Marxist reading of cybernetics, subsequently aroused some debates among cyberneticists as well as among the dogmatic representatives of the social sciences, which were not recorded in written sources. The latter, known by the abbreviation ‘Gewis’ for social scientists, belonged to a significant part of those philosophers or other scientists who, in the post-war period, although the level of their education had suffered due to the war, were able to occupy important positions in the various public institutions, benefiting in that period of the Cold War above all from that legitimizing slogan: “Where we are not, the enemy speaks in our place”. In this way, the ‘Gewis’ also seem to have infiltrated the party school in order to defend there a dogmatic, not to say Stalinist, view of Marxism. Already in the above-mentioned report of Rainer Thiel on the scientific consultation organized by the unit, the latter complained about the “dogmatic views of many social scientists and also of some editors of journals ” who had “inhibited their initiative” and who were responsible for the “backwardness of the GDR” in this field.

There continued to be sharp criticism from philosophers and natural scientists as well, but the charisma of Klaus, twice winner of the National Prize for Science and Technology and survivor of the death camps, denied these critics access to the journals. Thus, Klaus Fuchs-Kittowski’s (b. 1934) review of Klaus’s Cybernetics in Philosophical Perspective, written for the Deutsche Zeitschrift für Philosophie, was not published there. Fuchs-Kittowski accused Klaus of his own dogmatism in his introduction of cybernetics in this article, which was intended as a “contribution to overcoming dogmatism in philosophy” and which was also directed against the “Gewis”. It is most likely that cybernetics, as it had been introduced by Klaus, had finally become too powerful, especially with respect to the legitimization of some fields of the humanities, such as psychology, which was still little established in the GDR. Thus, according to a relatively scientific view, cybernetics had made it possible to define in psychology (or rather in ” Marxist psychology “) concepts such as those of labor productivity.

Five types of explanations were proposed at the beginning of this section for the gradual recognition of cybernetics. Following the influence of the political decisions of direction and the personal role of Klaus, the foreign literature introduced into the GDR now deserves a brief discussion. Apart from Norbert Wiener, whose second edition of The Human Use of Human Beings obviously met with a favorable reception, the Briton W. Ross Ashby also enjoyed the special esteem of East German scientists. Thus, one frequently finds the concepts of homeostat or multistability as they had been defined in Design for a Brain (1952) and in An Introduction to Cybernetics (1956). Léon Brillouin’s Science and Information Theory (translated into Russian in 1960) also provided material for numerous references in German works, this time primarily on the part of West German researchers: Küpfmüller (1954), Neidhard (1957), Zemanek (Austrian, 1959), and especially Steinbuch (1961), whose importance was pointed out by several contemporary witnesses.

The relative isolation of the GDR on the international level after the erection of the Wall (13.8.1961, demarcation period) does not remain without consequences either. Thus the director of the Institute for Control Engineering, H. Kindler, calls in the Dresdner Universitätszeitung the scientists of the different disciplines to unite now around the cybernetic theories, just as the political party would have done in the National Front at the foundation of the GDR. This political metaphor is all the more significant because it clearly expresses how behind the spread of cybernetics lies the will to rediscover a unity of knowledge such as might have been imagined in the 17th century.

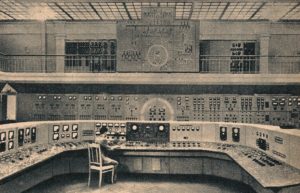

In the first isolated GDR, the “Gewis” lost their raison d’être, and under Ulbricht they lost influence. Finally, it remains necessary to add that cybernetics at the beginning of the sixties participated in remarkable technical progress, which, for example, gave rise to neologisms such as bionics and the construction of robots according to the model of living modes of functioning. In the field of automated computation, this period corresponds to the upswing in national production; in addition to VEB Carl Zeiss Jena, the Technical University of Dresden also set about designing computing systems. Since the D 1 of 1956 (“D” for Dresden – D 2 followed in 1957), cooperation had been established which enabled the realization of the Zeiss automatic calculator (ZRA 1: 500 operations per second, the thirtieth and last copy was installed under the responsibility of Klaus Fuchs-Kittowski at the Humboldt University in Berlin). In 1958, the physicist N.J. Lehmann, who had been exiled from the Soviets together with Manfred von Ardenne, also returned from the USSR and became involved with cybernetics in the development of “computing automata”.

All this worked together in the institutionalization of cybernetics in the GDR. In February 1961, Klaus was appointed head of a “Commission for Cybernetics” by the Secretary General of the Academy of Sciences, G. Rienäcker. Rainer Thiel, at this time a doctoral student of Klaus, became secretary of the commission until Heinz Liebscher succeeded him. The evaluation of the archives concerning this matter makes clear how the physicists, as well as the biologists and the academy administration, maintain a rather hostile attitude towards cybernetics. When in 1962 a “Section” of cybernetics was founded on the basis of a memorandum edited by Klaus, the latter asked the mathematician Kurt Schröder to take over its leadership after all, knowing full well that the new section would undoubtedly find easier recognition under the chairmanship of a renowned mathematician. Nevertheless, the Cybernetics Section remains relatively isolated, and until the establishment of the “Central Institute for Cybernetics and Information Processes” in 1968, one finds only very sparse contacts with the Institute for Control Engineering.

Until that time, the Cybernetics Section serves mainly to organize the hosting of various conferences after that first one hosted by the journal Einheit in April 1961:

January 1962: “Psychology and Cybernetics” at the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena.

March 1962: “Cybernetic Aspects and Methods in Economics”, mainly organized by the Economic Institute of the Academy.

March 1962: “Mathematical and Physical Problems of Cybernetics”, Institute of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics of the Academy. One counts more than 600 participants (four days).

October 1962: “Biology-Medicine and Cybernetics”, Physiological Institute of the Karl-Marx-University Leipzig

and finally, in the same month, the first large conference dedicated to all aspects of cybernetics:

“Cybernetics in Science, Technology and Economy of the GDR”.

Today, Heinz Liebscher remarks with regret: “At that time, we had no idea that it would be the last of its kind. “So what happened to cybernetics after this period?

4. Enthusiasm, ‘perversion’ and ‘normalization’ (1963-1969)

It is difficult to present a schematic overall view of the development of the so-called “cybernetic way of thinking”. It may be the inevitable distance of the historian from the events that lead to such astonishing deviations as the fact that the contemporary witnesses interviewed today sometimes hold completely different opinions than the archive documents would have suggested, but in any case it is obvious how several currents emerge at the same time without any single one dominating. The conference of October 1962, which was also attended by Czech and Hungarian representatives, certainly marks a decisive turning point “as the conclusion of a first developmental phase of cybernetics”, as Heinz Liebscher writes. Simultaneously to the sixth party congress, the corresponding congress acts appear, which forces the different protagonists to modify their respective attitudes, if necessary. In order to avoid simplifying this process of comprehensive historical complexity by choosing our categories, these different developments will be reported in the following only in a chronological outline, which merely provides the raw material for possible further research.

January 1963: Walter Ulbricht stands on the tribune of the sixth party congress and proclaims: “Cybernetics is to be particularly promoted” Klaus now dedicates a whole essay, titled “Cybernetics, the Program of the SED and the Tasks of the Philosoph?”, to comment this declaration. The cyberneticists seem to have the wind in their sails. Within this framework, a major economic reform is now being tackled with the ” New Economic System of Planning and Management of the National Economy ” worked out by the new candidates of the Politburo, Günter Mittag and Erich Apel. Far more than a simple plan for automation (a topic that Ulbricht, explicitly referring to cybernetics, addressed in his party congress speech), the NÖS presents itself as a solution to the crisis of 1960/61, which found its sad expression in the building of the Wall. Abandoning the current Seven-Year Plan in favor of a “perspective plan” (1964-1970), party officials apply theories of Libermann the Soviet as well as regulatory theories linked to the cybernetic movement on the other side of the Atlantic (such as the theory of marginal utility that emerged from the work of Morgenstern). They rely on management prediction and equilibrium. The powers of the planning commission are expanded and diversified: it becomes responsible for both the perspective plan and the annual plan. But the most profound revolution is that of industrial prices, which from now on are calculated as a function of production costs and planned profit rates. It should be noted that this epoch is marked by a recognition of sociological research, which until now has been more than disregarded.

In an essay of 1993, Rainer Thiel comes back to this period of hope for cyberneticists and recalls Klaus’ reformist intentions in the field of economics. “Georg Klaus (…) wanted to make the economy more flexible. With Marx.” In any case, the implication of cybernetics in the National Economy was to make it more dependent than ever on political fortunes.

In 1964, the goal of the East German economy seems to have been, if one follows Ulbricht’s remarks, to arrive at a “self-regulation”. Heinz Liebscher begins a series of seven radio broadcasts about the now officially recognized “cybernetic way of thinking”. A certain euphoria almost takes possession of some scientists, sometimes close to exuberance. As a representative example, we can cite this excerpt from a 1965 joint publication by Klaus (already seriously ill for three years) and Gerda Schnauß, which is mainly devoted to the fight against the effects of bureaucratism defined as “collection, transmission, processing and storage of information”, which, quite in contrast to cybernetics, suffers from a lack of adaptability. Starting from Shannon’s sampling theorem, the two authors, after giving the corresponding formula, further elaborate:

“Thus, the head of the VVB must first know what the frequencies of the signal function he is concerned with actually are. Their bandwidth can be determined. Then it results from it, in which time intervals must be controlled, arranged etc.”

If this theory were not applied, one would either risk losses in quality (the term is introduced around this time), or one would need a “superfluous administrative work “. With its suitability for economic forecasting, as introduced at the macro-economic level in the “forecasts”, cybernetics seemed applicable also in business management.

Heinz Liebscher’s small paper “Cybernetics and Management Activity”, published in 1966, met with an enormous response, not least because of its distribution in a circulation of 20,000 copies. In the ideal cybernetic society, it is no longer a matter of “directing” as in capitalist countries, nor of “controlling” as in the socialist economy, but of “regulating” in order to achieve communism. Two years earlier, in an essay on Wiener’s role in the development of cybernetics, the author had already noted that the “anarchy of production” in the capitalist system hindered the application of cybernetic principles, while these, on the other hand, fell on fertile ground in the socialist economy.

At the seventh party congress in April 1967, Ulbricht expressed himself even more clearly, announcing: “And if cybernetics helps us, then we will kneel down so long and so thoroughly in this new science until we master it completely. If one follows the memories of Rainer Thiel, then this was the moment from which now also the “Gewis” mentioned further above felt compelled to at least pretend to have a certain interest in the cybernetic cause. A philosophy professor from the Technical University of Ilmenau, Klaus-Dieter Wüstneck, is “elected” as a “candidate” of the Central Committee to preach the right doctrine there. This position now gives him access to all media and soon introduces him to the circle of cyberneticists. He actively participates in the progress of the institutionalization of cybernetics. He was appointed head of the commission “Cybernetics” at the Ministry of Higher and Technical Education and was charged with the introduction of teaching programs on cybernetics. According to the testimony of the main interested party, not only were the proposals of this commission never applied, but also hundreds of young cyberneticists trained in extensive exchange programs with the USSR returned to their country without the slightest hope of ever being able to apply the knowledge they had acquired. Cybernetics was never really taught, and its noticeable decline after 1969 was to seal the sad fate of cybernetic apprentices. Amusingly, it should be noted that, to our knowledge, cybernetics was sometimes the subject of lectures at the party school alone. Furthermore, ad hoc commissions were formed on the occasion of the Seventh Party Congress, namely in the Ministry of Science and Technology and in the Research Council. This latter body seems to have been the only one that actually worked for cybernetics. Wüstneck was a member of these official commissions, but also of the “secret strategic working group on cybernetics,” which was directly subordinate to Ulbricht. Now very critical of this institutionalization, Rainer Thiel today qualifies this strategic cybernetics working group as a “farce.”

In fact, this period is marked by the coexistence of valuable works such as the 1966 book by Klaus and Liebscher, Was ist, Was soll Kybernetik?, which was published in nine editions of 100,000 copies (including one licensed to the Federal Republic in 1970), Game Theory in Philosophical Perspective by Klaus two years later, and, on the other hand, writings such as Die Kybernetik im Kampf gegen die Kriminalität (Cybernetics in the Fight against Crime), a translation of various Soviet articles on the subject, which fortunately did not enjoy the same posthumous fame. If, at the local level, the elites may have heard talk of cybernetics, the factory managers or other brigade leaders were never in a position to apply these theories.

Moreover, Klaus’ book on game theory once again aroused criticism from dogmatic philosophers, who reproached the cyberneticist for his references to “enemies of the proletarian class” such as John von Neumann, Oskar Morgenstern, or Emmanuel Lasker. This series of new attacks, implicitly also directed against cybernetics itself (according to Klaus, game theory is one of the four aspects of cybernetics – see remarks above), was undoubtedly related to the Prague Spring, in the course of which intellectuals in numerous countries were accused of ‘revisionism’. Liebscher was then personally accused in an article published in Neues Deutschland on April 30, 1969. His accuser and judge, Kurt Hager, chief ideologist of the party, also refers to the discussions of the previous evening, when, on the occasion of the 10th plenary meeting of the party’s Central Committee, an essay published by Liebscher in the Spektrum had been sharply criticized. Incidentally, this must have been much more than a mere “criticism,” since the responsible editor-in-chief of the magazine was immediately removed from office. In short, it was probably above all the possible questioning of the party’s leadership role that caused the Central Committee to panic.

If the meeting of April 1969 very clearly marked an anti-cybernetic turn, Honecker’s now official assumption of power at the eighth party congress two years later robbed cybernetics of its last hope: solemnly, the new general secretary announced: “It is now finally proven that cybernetics and systems research are pseudosciences.” However, here too the situation is more complex than it might at first appear. Although Klaus’ preface to the third edition of his book Cybernetics and Society can be taken as a self-critique, he continues to publish on cybernetics no less, now admittedly in series such as “Critique of Bourgeois Ideology”, in which in 1973 Cybernetics – a New Universal Philosophy of Society appears.

The abandonment of the New Economic System is, of course, unfairly indebted to cybernetics, which served as its scientific foundation, so to speak. Since the beginning of the seventies one speaks of microelectronics or of computer science instead of cybernetics. Surprisingly, it seems to be economics of all things in which cybernetics has been able to maintain its place. The last conference on cybernetics in economics was held in 1985. In the other fields, cybernetics seems to have challenged the regime too much.

First conclusions and outlooks

What conclusions does the analysis of these relations between cybernetics and dialectical materialism, which can at least be described as “dialectical”, allow? Three different topics, which deserve more detailed investigation in a more comprehensive work, will be treated here: First follows a remark on the epistemology or sociology of science about the way in which a controversy is concluded; then, starting from a consideration of graphic representations, the special role of the concept of information in the effort to arrive at a unity of knowledge by means of cybernetics will be analyzed; and finally, as a theme borrowed from political history, the significance of reformatory currents among cyberneticists will be discussed.

In its entirety, this study is nothing more than an examination of a controversy over the validity of cybernetic theories. Initially, when cybernetics is still traded with the label of a “bourgeois science,” this controversy is banished from public debate and shifted to the realm of a semi-official and informal discourse, which today can be accessed solely through oral history techniques. The archival documents, essentially shaped by the mode and context of their creation, may serve as a link for the historian’s interpretation. It is only thanks to the conversations held that it becomes possible to understand how this or that apparently banal letter was able to have an enormous effect, for example, on the institutionalization of cybernetics. On the other hand, the contemporary witnesses speak today, of course, after the resolution of the tensions associated with the controversy, even if, as we will see, this history contains a current dimension. Periodically, political power intervenes with the aim of concluding the controversy in its interest. This becomes particularly clear in the well-established forms of discourse as expressed in the various party congress speeches: at the sixth and seventh party congresses, the controversy is to be ended in favor of cybernetics and this is even to be enfeoffed in the official historiography with the advances in computer science and aerospace; at the following party congress, on the other hand, it is definitely classified among the pseudosciences (” It is now finally proven …”, as Honecker declaimed). At present, there continues to be a close correlation between the available sources and the attitudes presented: For the period of the gradual establishment of cybernetics, before its official recognition, only the anti-cybernetic statements on the part of the party are found; later, under the Ulbricht era, very few traces of the ‘Gewis’ opposed to it are found, while today, after cybernetics has been more or less rejected by Honecker, all the witnesses interviewed, to a greater or lesser degree, present themselves as cybernetics victims.

It was suggested how cybernetics participates in an attempt to unify different disciplines by arranging them around it as a hard core. Among the various representations produced by cybernetics (such as theories, discourses, and – possibly non-discursive – practices) there is one particular type of representation that clearly demonstrates this unifying moment. It is the graphic representation.

First, consider the role of this representation in economics. For example, since 1952 in the USA, the entire macro-economic system according to Keynes is found as a representation in cybernetic terms, with a schematization of all completed control phenomena (Appendix 2.1). Considering the impression made on the reader by such a ‘scientific’ representation of an economic model, the latter is given a special legitimacy by this application of the ‘cybernetic way of thinking’.

The system is represented with the help of a “paper machine”, i.e. by means of a mere thought process, in which one must follow only the coefficients indicated at the arrows, in order to arrive at a result of calculations, which would have to be led in other way much more complex. Now one may be surprised to find the same type of paper machine again for the schematic representation of the processes in a centrally planned economy. This diagram is taken from the book by the Pole H. Greniewski, Cybernetics without Mathematics, which was widely read at the time in both the West and the East (Appendix 2.2). The graphical representation is indeed a means to make the structure of a modeling immediately accessible, because it is descriptive and is without requirements of previous mathematical knowledge. This modeling, with the use of the basic concepts of cybernetic theory such as feedback or information loop, participates in a quest for a unity of knowledge. New frahling methods such as those of the block diagram or the input/output analysis in the flow diagram (interconnection balancing) are widely used in this framework.

This type of cybernetic modeling, which is characterized by a certain design, appears in the most diverse disciplines. Thus, the same type of graphic representation is used to illustrate physiological processes such as the control of the blood sugar level or the reflex arc, and likewise to illustrate the functioning of the East German administration. For the last example, H. Metzler gives a very abstracted representation of the different levels with their corresponding “information blocks” (Appendix 2.3). The strictness of the pyramidal representation is softened by a dense network of arrows leading information to all levels. Likewise, this type of cybernetic representation is found in youth editions, a particular specialty of many countries in the East. For example, the Little Encyclopedia of Great Cybernetics, designed for readers 13 and older and translated from Russian, deftly blends the teaching of cybernetics with that of dialectical materialism (Appendix 2.4).

In all these examples, cybernetics is used to represent facts from a wide variety of fields under the same aspects. What is reversed along with the arrows in these diagrams is nothing else than information. Now, however, the problem of clarifying the semantic dimension of information remains the same. Information is a concept that becomes independent of relations of production or other social conditions. Now it could be related to this that the majority of the defenders of cybernetics in the GDR had been guided by reformist views or had expressed themselves implicitly critical of the system. This is a conclusion one must come to for instance when considering Robert Havemann, a scientific consultant for Einheit for two years and then, from 1963 on, a notorious dissident. In fact, the question cannot be decided unambiguously. In addition, many contemporary witnesses interviewed today like to present themselves as having always been critical of the party or the Stasi, although, of course, the present circumstances [after the fall of the GDR] suggest that they should take this position.

However, the questioning of the party’s leadership position and the demand for more flexible structures in the planning and decision-making process, in which the grassroots were to be involved, undoubtedly testify to the will to reform the country without, of course, abandoning Marxism. With regard to the economy, Rainer Thiel’s slogan on this point deserves to be remembered: “Make the economy more flexible. With Marx.” It should be mentioned here that the appearance of Thiel’s article in 1993 in Neues Deutschland provoked a fierce polemic within the editorial staff about the thesis according to which the GDR could have been “saved” by means of cybernetics.

Today, the concept of information is again being discussed in the circles of the PDS, the “heretical successor of the SED”. Although the term cybernetics no longer appears in the debates with the same persistence as before, commissions are being formed to investigate the effects of the ‘cybersociety’ on the possibilities of democratic decision-making, the forms of trade union work to be developed in view of telework, the possibilities of mobilizing citizens by means of the Web (in the area of the already much-cited ‘information highway’), and the like.

Thus, the relations between cybernetic theories and the organization of society are still the subject of passionate debates. If the history of the GDR could be viewed to a large extent through the study of its relationship to these theories, special attention to these current debates should in turn contribute valuable information about German society.