In part one of a three-part series, Amal Samaha begins her exploration of the concept of the labor aristocracy and its modern relevance.

For many, questions of the conditions for revolution in the developed countries hinge on the existence of an aristocracy of labor, a privileged stratum of workers that exists above the mass of proletarians, buoyed by higher wages, business unionism, or parliamentary alliances.1 Proponents of the thesis hold that they benefit from the imperialist world system, the immense concentration of wealth in a handful of countries. The debate around the existence of a labor aristocracy also cuts to the heart of a divide between social democracy and Leninism, a divide that centers around the belief in the viability of a pluralistic party with few programmatic conditions of entry. While the existence of the labor aristocracy was once an aspect of communist orthodoxy, it ceased to influence many revolutionary programs long ago, and the use of the term is now restricted to smaller groups. To many it seems incapable of explaining modern problems faced by the left, especially now that the difference between skilled and unskilled wages has been reduced, business unions flounder, and even the right wing of historical social democracy has been mostly forced out of the mainstream political parties.

However, the position taken in this series of articles is that a labor aristocracy continues to exist, despite the many political defeats such strata have suffered. I also seek to explain how the labor aristocracy reacted to and shaped economic conditions, and how revolutionary programmes must be transformed to take this into account. Part one will deal with the labor aristocracy in terms of its contradictory class position, and the consciousness that develops out of its simultaneously held but mutually antagonistic interests. Part two will demonstrate how the labor aristocracy grew between the period of new imperialism and the postwar era, reaching the summit of its influence, before suffering a period of relative political decline, with the collapse of many business unions and bourgeois-labor parties. The effects of significant global wage stratification on economic growth and the terms of trade are discussed, as are reasons for the continued presence of a non-aristocratic proletariat in the core countries. In Part Three, the strategic and tactical implications of organizing in aristocratized working classes are explored, including a discussion of present-day social democracy, the bourgeois-labor parties, and political sects.

This article is also ultimately a defense of a Leninist programme, although I dispute certain Leninist theoretical orthodoxies. The economics of this article are drawn in large part from the work of French-Greek economist Arghiri Emmanuel, one of the more prolific authors on the subject of the wage and their economic effects. The impacts of contradictory class positions, such as we find in the labor aristocracy, are explained in similar terms to the work of Erik Olin Wright. My goal in drawing together these three lines of thought – Lenin’s programme, Wright’s sociology, and Emmanuel’s economics – is not eclectic synthesis for its own sake, but finding points of mutual reinforcement.

I find that the labor aristocracy is a set of complex class positions, its interests and loyalties split several ways through different means of liberation or enrichment. It will not tend towards any independent clarification of these interests without intervention. A labor aristocracy has formed in several imperialist countries, which have now achieved relatively high general wages. Nowhere on Earth does a labor aristocracy constitute the entirety or overwhelming majority of a population, but in many countries, the complexification of proletarian interests is much more extreme. The aristocratisation of labor and its effect on the general wage, which is greatest in the imperialist countries, has been a disaster for the periphery, both in terms of accelerating the growth of the core countries and in contributing to a nonequivalence in trade. The best means of counteracting the global divide is not to await the ‘re-proletarianization’ of the core countries, nor indeed to advocate for it. Rather, only a renewed push for cross-border unionism, and core-periphery political ties between revolutionaries, can lead to a new period of global radicalism.

1: Class Position, Consciousness and the Labor Aristocracy

1.1: The labor aristocracy thesis and its context

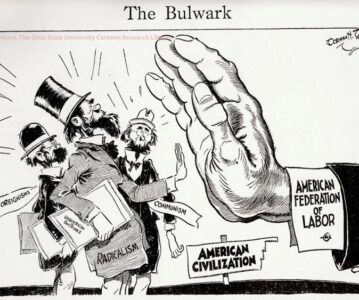

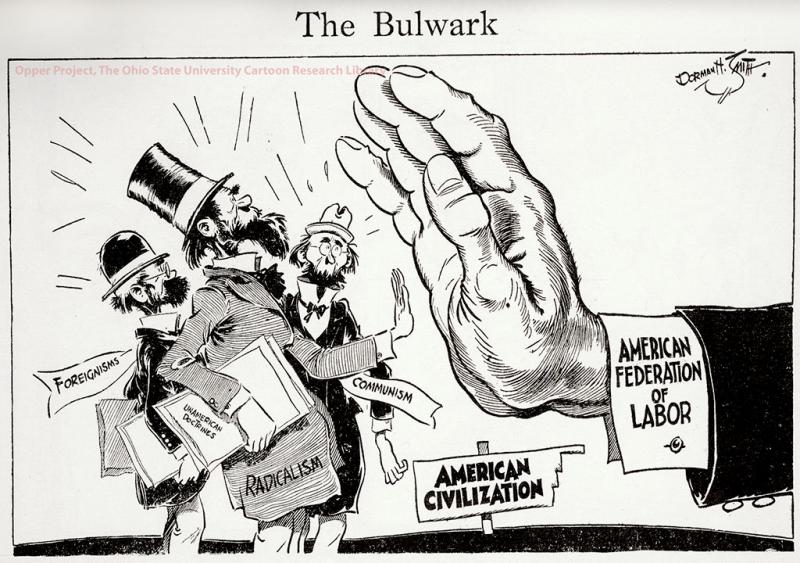

The first appearances of familiar political arguments about a ‘worker aristocracy,’ whether it was conservatives praising it as a bulwark against anarchy or radicals decrying their reformist approach, date as far back as 1837, becoming prominent in the Chartist struggles and their aftermath.2 Later, these arguments became part of the traditional Labourist account of the 1850s-90s period, describing a privileged stratum that profited off the period of Liberal-Labour compromise, which ended with the foundation of the Labour party.3 Outside of Britain, similar terms came to be used in political rivalries within early workers’ politics, such as by Mikhail Bakunin, or within the union movement, as in Daniel DeLeon’s critiques of the US AFL.4 Revolutionary Marxists like Friedrich Engels did not invent the concept of a labor aristocracy, rather as Eric Hobsbawm claimed, the idea of a privileged stratum within the British labor movement was already “familiar in English politico-social debate, particularly in the 1880s.”5 Engels innovation was not to create a concept from whole cloth, but to draw together existing material – the very old critique of artisan or craft union opportunism, and the Tory populist idea that the British working classes drew benefits from Britain’s empire – in a manner consistent with Marxism as it existed at the time.

Crucially, Engels believed that the labor aristocracy was historically transient, and would begin to wither as Britain lost its trade monopoly, which indeed began to falter in the 1890s. Thus a certain Engelsian orthodoxy formed, holding that the labor aristocracy did exist as a strictly temporary, late Victorian, British phenomenon. This was not necessarily Engels’ own position, since he had also described US workers as assuming “an aristocratic posture,” but his comments on Britain were more well-known.6 A version of this view was held by figures as diverse as Karl Kautsky and the Fabian historian GDH Cole.7 Today it continues to be upheld by labor historians following Hobsbawm.

Lenin’s innovation then was to connect Engels’ thesis to the phenomenon of imperialism in general, and thus tie it to an analysis of international politics. He did not go so far as to say a labor aristocracy was a permanent feature of capitalist imperialism but did suggest that the concept was applicable to more than just its late Victorian incarnation. In Lenin’s telling, drawing from the earlier theories of Hobson, Hilferding, and Bukharin, accumulation on an enormous scale allowed national industrial-financial conglomerates to form, competing with one another to export capital to frontier areas with higher rates of profit, accruing “super“-profits (profits at rates above what could be achieved without international movements of capital) that could be distributed in the home country. Much of this (Lenin even gives a figure of 10% of total superprofits) goes towards a “bribe” for a section of the working class in each imperialist country.8

“Bribe” is an powerful but somewhat imprecise word that might lead us to think that Lenin treats this as a purely financial transaction, an envelope passed straight from bourgeois to worker’s hands. In a speech to the second Comintern congress Lenin appears to resolve this confusion:

It is done in a thousand different ways: by increasing cultural facilities in the largest centres, by creating educational institutions, and by providing co-operative, trade union and parliamentary leaders with thousands of cushy jobs. This is done wherever present-day civilised capitalist relations exist. It is these thousands of millions in super-profits that form the economic basis of opportunism in the working-class movement.9

We can see that ‘bribe’ is intended in a very broad sense, in much the same way Engels spoke of “privileges” and “benefits” from the trade monopoly.10 It includes everything from general increases in the standard of living to more specific individual benefits in jobs for the “labor lieutenants.”11 The second misconception the word “bribe” introduces is the idea that the labor aristocracy is a conscious project of the monopolists alone, a conspiracy to delude the class. Sometimes it does take on this dimension, but in “Imperialism and the Split in Socialism” Lenin begins to point to another cause: labor aristocrats were engaged in a kind of class struggle, albeit one mediated through placing pressure on parliamentary reformists like Lloyd George, aimed at “securing fairly substantial sops for the obedient workers, in the shape of social reforms.”12 However “the question as to how this little sop is distributed among labour ministers, ‘labour representatives’…labour members of war industrial committees, labour officials, workers organised in narrow craft unions, office employees, etc., etc., is a secondary question,” although there were both political rewards (“lucrative and soft jobs in the government or on the war industries committees, in parliament and on diverse committees, on the editorial staffs of “respectable”, legally published newspapers or on the management councils of no less respectable and “bourgeois law-abiding” trade unions”) and economic ones, including high wages, “insurance” and workplace reforms.13 These more technical questions were uninteresting, and Lenin’s answers to them were fairly gestural, compared to the urgent political point he was trying to make.14 The source of the deformation of socialist parties into nationalism, racism, reformism and a thousand other hopelessly ideological notions wasn’t coming from outside the workers’ movement, but from within.

This was a considerable deviation from Marxist orthodoxy at the time. Until then the predominant view in the Second International was that ideological deformation was a consequence of sections of the proletariat being too close to various dying or enemy social classes, and getting delirious on the fumes they gave off.15 The workers were being deluded into a belief in regressive feudal notions by the aristocracy and peasantry, or absorbed into timid reform campaigns by petty-bourgeois liberals, or were becoming faithful tory lapdogs of their industrialist bosses. As the rural semi-proletariat integrated further into the cities, and the artisans and petty traders were annihilated by competition, the polluting influence of retrograde ideology would be counteracted by the intensification of class struggle and the polarisation of society into two opposed camps. The obvious programmatic conclusion of this process was that the entire proletariat should be brought into parties of the whole class, where free debate and development could take place, which would naturally gravitate over time towards the most scientific expression of proletarian interests (hopefully Marxism). There were still many paths to the political nullification of the working class but until the labor aristocracy thesis, these had all seemed to be historically transient and leading away from the workers’ movement rather than running alongside it.

1.1.1: The craft unions

Lenin’s break from orthodoxy took place in the context of a drastic change in conditions faced by the workers’ movement. It should be emphasized how unprecedented the widespread growth of an economically privileged working strata was. As Emmanuel says:

Something happened towards the end of the nineteenth century and this conventional [belief that wages were tied to subsistence cost] ceased to reflect reality. This was a radical change in the distribution of power among the classes within the bourgeois parliamentary system in the industrialized countries, which had the effect of finally lifting the price of manpower out of the swamp of the mere physiological survival of the worker. In order to appreciate the effect of this event it suffices to remember that, for thousands of years, the worker’s wage was the most stable economic magnitude which existed. The purchasing power of the average European worker around about 1830 differed very little from that of the worker in Byzantium, Rome or the Egypt of the Pharaohs. In the following century and a half it was multiplied by ten.16

This rise in wages was of course uneven. Taking builders’ real wages as our point of reference, in the Anglophone settler-colonies, wages were already 4-5 times higher than in Europe in 1870, thanks to labor shortages caused by the abundance of stolen land. Enormous differences in wages between the settler and non-settler core countries remained as late as the 2000s. In Western Europe skilled worker wages were largely the same for the major colonial powers in 1820, but began rising in Britain around 1870, and the other powers around 1890. By 1910, Western European skilled worker wages were all roughly comparable, with the exception of Italy. Thereafter wage rises continued steadily, especially during reformist governments. In Western Europe, wages rose 9.6 times over 1910 levels by 2000, while in the settler-colonies they rose 2.2 times, since their starting point was vastly higher. The rate of peripheral wage rises is too diverse to reduce into generalizations, but at every stage these wages were vastly lower in absolute terms.17

This rise in wages was preceded by another historic shift: the reduction in general unemployment from as much as 40% of the working population in the 18th century to under 10% by the end of the 19th.18 Some wage growth might then be explained by labor scarcity, while another part might be explained away by the rise in mass education (literacy rates in Britain had risen from 53% in 1820 to over 80% in 1900).19 However, the strongest influences on wages were political in nature.

Wage increases coincided with a rise in the power and influence of craft unions: economic associations of workers organized by their trade and level of skill. These unions, and the skilled workers they represented, did not emerge all at once at any specific point in capitalist development, rather they were already there from the beginning, gradually evolving out of pre-capitalist artisans and guilds.20 Craft unions became more prominent in late 19th-century political life as skilled wages in specific industries rose, while the competitive pressure upon skilled workers to assimilate into the unskilled workers intensified. Around the same time, political alliances of skilled workers and industrial bourgeois, between “manufacturer and mechanic,” became more common. Revolutionaries of all stripes were highly critical of these methods for the reformist mindset it seemed to encourage.

However the radical critique of craft unionism should not be that it was ineffective at achieving the narrow goal of increased wages for one section of workers, when compared to alternatives like industrial unionism (the organization of workers across industries regardless of skill). Across the developed nations, industrial unionism, considered from this shortsighted view, was mainly effective as a means of getting large numbers of workers beaten up by the gendarme, cops, and scabs. But industrial unionism was also very effective at bringing to bear the political power of the whole class, and terrifying the states, which were aware of the ability of strikes composed of only a few key industries, the ports, and railways, to shut down whole economies. This sent them scrambling to undermine such associations at any cost. Industrial unions were suppressed, their modes of organization criminalized or forced into compromised positions through compulsory arbitration schemes or eventual entry into labor federations dominated by the craft unions. As is typical of situations wherein greater and lesser evils are presented to states, the craft unions were doubly empowered by the profound fear of their alternative and found even more support within governments. The preference for loyal, national unions over disloyal internationalist ones, contributed considerably to the growth and empowerment of craft unionism, with a powerful union bureaucracy at its helm, integrated into the state via the parliaments.

This is not to say that there was anything inherently reactionary about well-educated skilled workers that led them to join craft unions. Quite the opposite, skilled workers formed the core (and sometimes the majority) of every Marxist organization to have ever seen a revolutionary opportunity, able to grasp radical concepts easily and organize themselves effectively. This was just as true in the periphery as in the developed countries. In Germany, it was the skilled metalworkers that first formed the revolutionary councils in 1919. In the backwoods Russian Empire, the quite well-off Latvian working class proved an effective revolutionary force.21 In Iraq, on the eve of the missed revolutionary opportunity of 1959, some 60% of the Communists were educated skilled workers, the sons of the rural religious literati, salaried professionals and state employees, mainly teachers.22 But the introduction of significant privileges over and above the rest of the proletariat introduces among skilled workers the possibility of petty-bourgeois aspirationalism, elitist attitudes, and various regressive concepts and organizational forms. Both possibilities are contained within this stratum of the working class from the start, which was why it was so important to convince the skilled workers that immediate gains made through craft unions and cross-class alliances would come at an unacceptable cost.

But the cost came only on a more abstract level, and faced with the choice between short-term gains or the long road to revolution, winning over skilled workers was often an uphill battle.23

Whereas industrial unionism tended to increase workers’ awareness of the social nature of production, their role in an integrated whole, and their connection to workers not only in other branches but in other nations altogether, craft unionism did precisely the opposite. At best it led to an awareness of the shared interests of the skilled workers’ most immediate compatriots, at worst it taught them the value of their labor power and theirs alone, and that collective bargaining was but an extension of competition between different groups of workers. This narrow field of view extended at most to the borders of the nation, for the purposes of protecting the national labor market from migrant labor, competition which might exert downward pressure on wages. Marx had as early as the 1860s noted that it was the craft unions of England that led the charge against Irish immigration, and that this antagonism was “the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power.”24

As we can see, consciousness is not only an expression of economic conditions, and of locations within the matrices of class structure – it also reflects the structural organization of resistance to adverse conditions. In the case of craft unionism, the structural organization of this resistance had a profoundly negative impact.

This may not seem so relevant now, given that the dichotomy between craft and industrial unionism has been sidestepped by history. In many developed countries, individual craft and industrial unions have long since been forced into large general unions (which correspond neither to trade nor industry) to preserve their remaining political and economic power in the present period of stagnation.25 However we will see that despite a change in their basic structure, many unions continue to play the same role as the craft unions of old in national politics.

1.1.2: Imperialism

The thing that separates Lenin’s critique of the labor aristocracy from simply a critique of craft unions, bourgeois-labor alliances, or privileged strata is the idea that a labor aristocracy is connected to international imperialism.

Around the same time as many European workers were beginning to organize themselves into unions on a newfound scale, politicians from all sides were watching on, curious about the new political strata, and eager to find out how it might benefit them. It was not just a coincidence that the conditions for the vast expansion of colonies and a rise in talk of social benefits matured around the same time – it was also a conscious process. In Britain, it was Disraeli who first saw the political potential of tying advocacy for colonial expansion to the promise of social benefits, while in Germany it was Bismark and his loyal kathedersozialisten. In Italy, prime minister Giovanni Giolitti was immensely successful in using social reforms to convince the working class of the benefits of foreign conquest. What was initially the strategy of a relatively unstable alliance between the craft unionist wing of the workers’ movement and traditionalist conservatives or liberal reformers was later taken up by some parties of labor. In Britain, the Labour Party soon committed itself to a policy Tichelman calls ‘ethical imperialism,’ while in the French SFIO and right wing of the German SPD, support for a “socialist colonial policy” was more unapologetic. By far the worst were the Dutch Social-Democrats, whose appeal to the legitimacy of “socialist” colonialism nearly carried the day for the social-imperialist camp at the 1907 congress of the Second International. Even among more left-wing parties, the extreme unpopularity of “unpatriotic” anti-imperialist policies led to a certain reluctance to discuss colonial matters.26

The political environment of the turn-of-the-century made it inevitable that Engels and Lenin, in looking for the culprit that might have paid off the craft workers, should settle on the industries most connected to foreign trade and imperial expansion. This was already a well-worn talking point, albeit one rarely framed in a negative light. But the question of whether the connection between imperialism and socioeconomic benefit was mostly a rhetorical construct of 19th century political alliances is worth some investigation.

Since it is entirely inarguable that there was often a conscious link between imperialism and social privileges in early 20th-century labor politics, only a few explanations would suffice. Either the social-imperialist labor leadership of Europe received no supplementary benefit from imperialism and were simply duped en masse into supporting imperialist expansion, or it did receive benefits and was a willing participant. Were these benefits of a primarily political or economic nature? If it received quantifiable benefits, then was it granted these as a bribe by monopoly capital, or did it reach out and seize them itself?

Plenty of doubt has been piled on the suggestion that the “bribe” could have been paid out of special profit rates, or the proceeds of direct colonization. Opponents of the labor aristocracy thesis have contended that the superprofits necessary to maintain such a strata have never been adequately identified, nor is there much of a reason why individual monopolies would pay workers superwages out of these sums of their own volition.27 While capital in theory moves towards areas with the highest rates of profit, investment in the truly ‘greenfield’ underdeveloped regions was negligible during the whole era of direct colonization.28 While colonization created enormous benefits for Europe as a whole, it is true that in the 1880-1914 period these benefits did not take the form of especially high profits for the direct colonizer, and the European countries that instead invested in other core countries, and which did not shoulder the biggest costs, were the ones which saw more rapid development. These points are often raised by apologists of imperialism to demonstrate that the New Imperialist period as a whole was an unprofitable venture, which is clearly untrue when we consider divergent changes in the rate of growth for Europe and the colonies, but there is a rational kernel in that the benefits of imperialism did not always take the form of profits higher than those of imperial rivals. This is in part because the movement of capital within Europe served to redistribute the benefits of direct colonization, allowing Germans to profit from American expansion or Swedes to profit from the British Raj. There is a division of labor between Imperialists just as there is between the core and periphery, as some are more willing and able to shoulder the costs of military intervention, market penetration, and resource development than others.29

Rapid colonial expansion from the 1880s was mostly undertaken by states seeking to control strategic trade routes and markets. This was certainly conducted with the goal of eventual profits via trade monopolies, but in practice often only succeeded in denying opportunities to competitors. If there was colonial expansion outside of the few areas with strategic markets, then it tended to be led by small-time petty bourgeois farmers and speculators, who did not reinvest profits at home. There were exceptions in the case of major entrepots, mining, oil, and sometimes monopolistic land speculation like in German Kamerun, but such hubs of colonial activity and investment were often few and far between.30

There was capital export on an enormous scale during this period, and a doubling of the rate of capital formation in continental Europe, but most capital export was Foreign Direct Investment between core countries, or in the semi-periphery of more established settler colonies (the US frontier, Brazil, etc.). Where there was peripheral FDI, it resulted in next-to-no growth, and in fact, there would have been net capital exports to the core, as almost all profits were reinvested there.31 Capital export to the periphery was prompted by the demand of metropolitan industry for particular raw materials, often for manufacture into goods sold on peripheral markets. The image of imperialist capital export flooding the world, and actively developing it while reaping vast superprofits – which seems to be the popular interpretation of Lenin’s theory whether or not it is the correct one – is not supportable. The periphery was not flooded but rather starved of capital on the eve of 1914. It is perfectly possible to incorporate an analysis of capital export into our understanding of imperialism in Lenin’s day, but it should be done with several provisos: 1) it was rarely exported to the most underdeveloped regions, whatever their rate of profit 2) the imperialism of capital export depended on where the proceeds were reinvested, or what kind of dominance was enforced, and 3) capital export to the periphery was mostly subordinated to the requirements of competition for global markets.

Between 1830 and 1913 there was the greatest global market suppression in history as peripheral industry shrunk from 60.5% to 7.5% of global industrial output, utterly out-competed by the flood of goods from the industrializing core. While this began to reverse in 1900, growth rates remained abysmal until decolonization.32 Before the period of intense wage rises and specialization, these goods were usually cheaper than peripheral alternatives, and so imperialism did not act through distortion of the terms of trade as it later would. This historic change in markets, which preceded the expansion of direct colonies, represented the creation of a modern periphery.

The profits of imperialism for whole countries then, come primarily from the benefits of national industry gaining advantages in these global markets. There are several potential causes for this advantage, and the specific reward differs with each case. As a global market for commodities begins to develop, commercial capital develops to take advantage of the differences between countries (in productivity, natural abundance, etc.) to profit off of simple inconsistencies in local and foreign market values, reinvesting this profit in deepening trade monopolies. While recognizably ‘capitalist’ production oriented towards exchange via mercantile intermediaries has been a sporadic factor of human development for far longer than is often thought, and this was hardly confined to Europe, it was only after the industrial revolution that a recognizable periphery formed out of the nations unable to compete with the sheer quantity of European goods.33 Those countries which maximized export volumes were those that were able to utilize the full extent of their productive capabilities (otherwise limited by a problem of general overproduction explored in section 2.2.1, forthcoming). By the late 1800s the development of banking, the effects of the long depression, and the collapse of a British monopoly on trade with the periphery combined to increase the rate of capital formation and its export, especially to the lesser imperialist powers and settler colonies. While capital had been exported to foreign regions in some quantity since the Middle Ages, it is only in more recent centuries that capital has been sufficiently mobile between countries, and available in sufficient magnitudes, to exert much influence on international rates of profit, moving wherever higher rates of profit can be found and bringing these down to a general level through increases in supply. By the time a tendency for a general rate of profit formed, not only did some nations benefit from the repatriation of profit from investments, but more capital-intensive countries began to benefit from the formation of prices of production, which allowed them to sell more for more, though these were not always the imperialist countries. Later, imperialist countries with high general wages gained the ability to sell less for more (both cases are discussed in section 2.2.2, forthcoming). Trade surpluses, the repatriation of the proceeds of direct investment, and the creation of high general wages acted to concentrate investment in the Imperialist countries while increasing capital costs and declining profits tended to repel it.

There are many historical forms of imperialism, but it is that which takes place after the formation of a tendency towards a world rate of profit that deserves to be called capitalist imperialism. Only after this point are the iniquities caused by international trade simply the product of the operation of the laws of value, accumulation, and profitability on a world scale, rather than transient problems of inadequate mobility in goods or capital. In this manner, we do not need to identify special profit rates, or some additional iniquity not present in ‘normal’ (national) capitalism, rather capitalist imperialism is the process of some capitals gaining advantages out of existing uneven development in order to supplement their mass of surplus value by distorting the development of others or dictating the terms on which it can take place. Often this imperialism results in no profits at all, especially in its hyper-competitive phases. Rather, imperialists pursue policies to deny opportunities to rivals and seek dominant positions that don’t always come to pass. In such cases, it is still imperialism.34 The desire for profit is a driving force of imperialism, and yet extra profits are not the necessary result. Where they are the result, it is mostly via a greater mass of profit on traded goods. Often more telling than profits are the general patterns of global investment towards such countries. FDI can be a part of the war of position to gain market dominance, depending on how it is actually used, as well as conferring its own benefits via transfers within multinational firms and portfolio investment.

Identifying the unstable profits of imperialism with the rewards of international market competition fails to help us explain why super-wages would be paid out of these sums. But it seems clear that they are not paid directly, rather via various social and political intermediaries, mostly those incorporated into the state. In citing broad social, even “cultural” benefits as the result of the bribe in his speech at the second congress it seems Lenin was pointing in this direction. They included rewards for national loyalty by the states – political standing, legal protections, and other unquantifiable prizes. The labour bureaucracies of Europe were aware that such rewards were up for grabs in 1914, and for a time they were even willing to send workers to kill one another to gain them.

If there were economic benefits to the core working class (in cheaper goods, or lower unemployment) that were the direct result of the advent of inter-imperialist competition, then these were still relatively small to begin with, limited by economic crises and the still quite low general wage. In Britain, a high-waged stratum certainly did exist, especially among engineers and builders, but its ‘privileges’ might seem underwhelming to us now. Gray, citing Rowntree, notes that wage differences within the English working class around 1900 were quite small in absolute terms, but very small differences carried great weight in status.35 Small economic differences translated to major socio-political divides, and this is what made a labor aristocracy an observable social phenomenon.

Craft unions did not necessarily become prominent during this period because skilled workers were experiencing greater economic rewards than before, but because there was escalating pressure to assimilate into the larger mass of unskilled or casual labor. This was delayed in Britain for some time due to the size of the handicrafts sector producing for colonial markets, but the threat of losing a ‘respectable’ position amid the lower-middle-classes felt very real. For skilled metropolitan workers, it was the prospect of losing what might appear to us as quite meager privileges that drove them to seek parliamentary alliances and more exclusionary union strategies. Where craft unions were not formed this proto-aristocracy was at greater risk of re-proletarianization.

Wages did begin to increase substantially as unions grew and global porkbarrel politics became widespread, but it was not a matter of monopolies granting them. Instead, craft unions successfully organized themselves in parliamentary politics to secure higher wages. The chief benefit of imperialism for certain working-class strata was not wage rises so much as the potential for wage rises to be won. The climate of inter-imperialist competition meant that this was accompanied by social-imperialist politics. We need not identify a special source of profits out of which this was paid, instead, we need only note that average core rates of growth grew from 0.6% to 1.7% from the mid-19th century to 1913.36 Much of this would no doubt have taken place even without access to colonial markets, but autogenous development is difficult to separate from imperialism post hoc.37 Whatever its source, the social product was now sufficient for a labor aristocracy to form itself out of the craft unions and bourgeois-labor parties by demanding a share. For the first time in human history, a significant working stratum was able to secure wages well above the level of mere reproduction.

1.1.3: The labour aristocracy thesis in the present day

If the signifiers of the labour aristocracy of Lenin’s day seem to us as relics of the early 1900s, then this has only made the abandonment of the theory all the more easy. The craft unions are gone, and it is difficult for us to imagine a popular imperialism among the workers’ movement, of the type that nearly convinced the Second International of the benefits of a “socialist colonial policy” at the Stuttgart congress.38 The forms of mass culture concomitant with social-imperialism – the colonial exhibitions, orientalist advertising, the spectacle of subjugated peoples – seem to us as only an echo of their former prominence in the popular imagination.39 Imperialism is denied rather than celebrated openly.

In addition to the apparent decline of the cultural and ideological forms associated with the classical labor aristocracy, the theory has also lost support due to its connection with Lenin’s theory of an imperialist stage of capitalism, which if interpreted as merely a theory of net capital export to the colonies from the core, or of special monopoly profits, is certainly empirically flawed.40 There does not seem to be much defense of these concepts even by very orthodox Marxist economists.41 Charles Post has become particularly prominent for his criticisms of the labor aristocracy idea and what he sees as its economic basis.42

But ideas are not generally discarded only because they contain empirical flaws or have fallen out of academic vogue, so long as they are useful. A more direct reason for the abandonment or understatement of the labor aristocracy thesis was that it came to clash with what most ostensibly Leninist parties saw as their strategic interests.

The labor aristocracy thesis continued to be cited in Comintern documents after Lenin’s death, especially with the republication of his Imperialism in 1926, whereafter it became a source of justifications for entirely different attitudes towards the union movement as Comintern policy zig-zagged. During the Third Period, the entire non-communist workers’ movement could be dismissed as opportunist beneficiaries of colonialism, and thus unsuitable for temporary alliances with the vanguard. When official communism became enamored with the Popular Front strategy from 1935, due in large part to the diplomatic interests of the workers’ states (to assuage fears of red expansionism, avoid confrontation, and form defensive alliances with bourgeois states), the labor aristocracy thesis was instead used to explain the disunity of the union movement and its unwillingness to join with the vanguard.43

This ideological zig-zag proved untenable, and the latter theory too was abandoned over time. The Popular Front strategy necessarily included long-term alliances not only with sections previously considered to be part of the labor aristocracy, but also amenable sections of the ‘non-monopolistic’ bourgeoisie, as part of the anti-colonial or anti-imperialist front in the periphery, and the anti-fascist or anti-monopoly front in the core. Naturally, polemics against the influence of worker-aristocratic ideas had little purchase while far more deformative influences were being tolerated. Lenin had pointed to inter-imperialist conflict as a potential countertendency to the aristocratisation of labor, and Marxist orthodoxy holds that wages for skilled work will decline relative to unskilled work.44 In parties like the CPUSA this came to provide a theoretical justification to consider the labor aristocracy as once again historically transient.45 In the increasingly Eurocommunist CPGB there was a push to revert to the Engels/Kautsky orthodoxy that the labor aristocracy ended after the 1890s, theoretically justified through the historical work of Hobsbawm and Robbie Gray.46

Large sections of critical communism effectively tailed the CPs into the Popular Front model (by entering into them, or into the bourgeois labor parties) in an effort to push them to the left. Otherwise, they abandoned the labor aristocracy thesis as part of a larger project of lopping off all the bits of Marxism that failed to appeal to student recruits.47 Some remaining groups and individuals held on to the labor aristocracy thesis, with some even proposing that it had grown since Lenin’s time in a modified form and that its growth was contributing to an intense period of retreat. A text that probably demonstrates the extent to which the labor aristocracy thesis could be advanced without breaking with Lenin’s economics is Elbaum and Seltzer’s 1982 paper for the NCM group Line of March.48 A more orthodox academic defense of the Leninist approach was presented in 1974 by the CPGB labor historian John Foster, but this was not influential.49 If the thesis survives today it is generally in small sects, which have avoided ideological notions through the very same orthodox mentality which has generally made them reluctant to develop old theories further.

The conclusion that the classical labor aristocracy has grown, and continues as a factor of working-class reformism and social imperialism, is correct but insufficiently concrete. To analyse how it has grown, and what social and economic effects this has had, a more granular view is needed. It is necessary to differentiate between those aspects of labor aristocracy which were products of its infancy, or of specific conditions in the early 20th century, from those which are still present in its ‘mature’ form. Craft unionism, pro-colonialism, and the mass membership of bourgeois-labor parties may be gone, but the underlying broad tendencies: the stratification of labor, social imperialism, and opportunism remain, finding different expression in the realm of ideas and social practice.

1.2: The Complex Determination of Class Position and Consciousness

There is a glaring contradiction in Lenin’s theory of the labor aristocracy. The labor aristocracy is an advanced section of the working class, generally more ‘left wing’ than the strata below it. It is well-organized, relatively conscious of its position and most immediate interests, with its own complex ideas, theorists, and politicians, and its own struggle to wage. At the same time, it is a representative of deformative interests within the workers’ movement, loyal to its bourgeois masters when it matters most, unconscious of its true potential, with nonsense ideas that fail to conform to its practice. It is successful because it is compromised, and it’s compromised by its success. It is both fiercely independent and doggedly collaborationist. This contradiction isn’t contained in Lenin’s thought, a failure at theorization, it is a contradiction that exists in reality.

Any analysis of the labor aristocracy has to take into account the complex determination of class position that could result in a stratum with such contradictory consciousness.

There are always multiple forces pulling on economic classes, a constant flow of individuals and ideas between classes amid changing conditions, and an ever-present but limited mobility underlying the actual expression of class in conscious thought. Ties, loyalties, patronage – political and social dependencies between groups and individuals – can compound this. As a result, contradictions in the expression of consciousness do not always mean that there are contradictions in the reality of class position, contradictions of class-in-itself. The overused phrase “false consciousness” might be more appropriate in such cases. There is clearly some disconnect between the inception of an idea in the interests of a class or strata and its actual expression, which can occur elsewhere. The New Left historian Gareth Stedman Jones tried to capture this reality in a widely cited passage:

As a social and ideological phenomenon, the labor aristocracy undoubtedly existed in mid-Victorian England; but it is impossible to explain its existence in abstraction from the general political and ideological conjecture. Labour aristocratic attitudes do not coincide in any simple way with particular strata of the labor force…50

There is certainly truth here. Labour aristocratic ideas do often spread to the whole class, and most writers on the subject agree that the ideas of individual workers have little to do with their class strata. But it is not as individuals that we engage in politics. More important questions include: whose interests do the ideas of individuals suit? In what way do different classes and strata seek to proliferate these ideas? It is also true that the Victorian labor aristocracy is impossible to detach from the specifics of Victorian politics and ideology, but this shouldn’t be interpreted to mean that such a labor aristocracy doesn’t reflect a set of class positions that could arise in other societies, wherein it would find different expressions when combined with new political and ideological contexts.51 Jones’ critics were right to point out that his version of the labor aristocracy thesis was quite vague, indistinguishable from other Marxist theories of false consciousness and ideology.52 If the idea of a labor aristocracy is to retain any use, then it must be related to class positions in some way.

There can also be contradictory expressions of consciousness that do reflect a more fundamental contradiction of class in-itself, in the basic economic life of groups and individuals. If they persist over time, these contradictory positionalities can forge a more stable social stratum within classes. Erik Olin Wright put forward the best-known theorization of these positionalities, calling them “contradictory class locations.”53 But the fact that class was not so simple as an identification with this or that formation of consciousness was well known long before him, at least before the popularisation of the humanist Marxist tendency to collapse class in-itself and for-itself into one another.54 The individual relates to class first as a “bearer of roles.”55 From these economic roles (boss, worker, landlord etc.) defined around unequal rights and powers to useful property or its fruits, arise a set of interests that can contradict one another.56 These interests can exist in a relatively pure form, and on the most abstract level the class struggle is reducible to conflict between the most basic groupings of these interests, but on a more specific level it is clear that different interests can be held simultaneously. The tension between these mutually antagonistic but simultaneously-held interests is stronger the more consciousness of one or another develops. When the time comes to express these interests as ideas and narratives or to fight for them through political practice, one or another interest may win out; or else ideologies which preach class peace and the reconciliation of different interests may be more attractive. The worker-landlord might fight on the picket line, and will usually discover a reason not to stick around for the rent strike, but will not necessarily see any contradiction there. On the other hand, various external factors can cause one aspect of a person’s class position to affect their consciousness more deeply than another, and cause them to gravitate towards some alliances over others. These interests relate not only to class positions held in the present, but also those in the past and future, and so consciousness may lag behind or anticipate changes in true position.

A good example of complex positionality can be found in the classical Marxist theorization of the revolutionary peasantry. The 18th-century French peasantry was divided in its economic life between richer propertied peasants closer to the petty-bourgeoisie, and a mass of tenant farmers, with various shades in-between. Nonetheless, a distinct social entity with a common consciousness (a progressive one at that) existed alongside the modes of economic life peculiar to feudalism. So long as the peasantry shared a common form of exploitation – seigneurial rents and taxes – a peasant consciousness aware of its interest in land reform could exist. This changed in 1789 with the abolition of seigneurialism, after which the peasantry no longer had such a strong shared interest and disintegrated as an independent social class – it is well-known how revolutionary peasants simply dropped out of political life soon after August 4.57 As Marx tells us in the 18th Brumaire, what was left was a more homogenous mass of smallholders, their political consciousness stymied by the narrowing of their interests to little more than the maintenance of their means of subsistence. But even then their consciousness was not so simple: the peasantry still played a role in political life through proxies, with some peasants placing their hopes in the bonapartist regime, and others, especially rural lumpens and those immiserated through taxation, placing their hopes in the urban proletariat.58 What is interesting here is that over the course of the bourgeois revolution and its aftermath, a class with major contradictions in its economic life but few antagonisms in its consciousness transformed into a class with few contradictions in its economic life but major antagonisms in its political consciousness.

The specific forms consciousness takes, then, are a modality through which objective interests are expressed. This modality takes the form of narratives and ideas, which vary in their coherence with one another or correspondence to empirical reality or social practice.59 These interests are themselves complex responses to economic life, arising out of unequal relationships to useful property or the rewards associated with it

While there is such a thing as a precise, scientific expression of a class’ interests in conscious form (which alone deserves to be called “class consciousness” in a true sense), in reality only the proletariat at the absolute pinnacle of its self-organisation, able to disconfirm mystifying ideas through practice, can develop such a thing.60 For all other classes or sets of class positions, the mystification of relations is itself in their objective interests: the landlord, capitalist, and smallholding peasant alike would prefer to believe that their assets were granted through divine grace, natural rights or pure gumption, and their position is only strengthened by this belief. This is still the case even if these interests are held simultaneously to those associated with a proletarian class position, although the question of whether the individual benefits from this belief is naturally more complex.

While Marxism aims to be a scientific expression of objective proletarian interests, no Marxist organization has been or ever will be composed purely of proletarians whose consciousness is subject to simple determination.

Recognizing the existence of complex class positions is superior to a view of class position as definitively determined by different quantities of income. A common-sense view is given by the Marxian economist Michael Roberts who, in critiquing the Keynesian Jonathan Portes, argues that even though half of the US working population receives some form of investment income they are not in any sense “capitalists,” right up until the point where their investment income outstrips waged income, and this is a hard line we can draw between classes. Roberts is unable to dispute the basic facts of Portes’ claim that roughly half of the US population receives investment income, which has been confirmed several times.61 Nor can he claim that these persons are ‘proletarians’ using quotations from Marx or Engels.62 Roberts is correct in asserting that they are “working class,” and that it would be reductive to call them capitalists per se, but he implies that there is nothing complex about their class position, accepting a simple binary of worker and non-worker. He concedes that there is a small group, some 2%, whose income is mainly derived from investment but who still work as employees, and these aren’t workers.63 Presumably, these people, having one day checked their income statements, took off their flatcaps and put on their tophats. Instead, this whole half of the US working population is working class insofar as it works, and petty-bourgeois insofar as it earns a passive income through investment – it bears both roles. They are in a contradictory position and their consciousness will develop accordingly.

1.3: Characteristics of Mature Labour Aristocracies

In order to understand the changes the labor aristocracy has undergone over the last century it is first necessary to look at its class position with the help of the tools discussed in the previous section.

So far I have mainly treated the labor aristocracy as something which arose among skilled workers in Europe from the 1870s-1890s. This was not always the case – similar social formations existed much earlier in the 19th century due to extreme labor shortages in the settler-colonies64, or else they arose through specific forms of racial and national oppression, such as the white labor aristocracy in the US South under Jim Crow.65 In such places it was less the case that a person would enter the labor aristocratic institutions due to the bargaining power that came with being a skilled worker, rather a person would be pushed to become a skilled worker due to the privilege of being a part of the racial or national aristocracy. Causality in such cases is often reversed due to the primacy of maintaining social systems like white supremacy at any cost. For now, however, I will focus on the aristocratisation of skilled labor in the metropole.

From the very beginning, workers with different sets of skills are the subject of a peculiar and seemingly illogical process fundamental to the capitalist mode of production. This is the reduction of qualitatively incomparable concrete labors into unequal quantities of homogenous abstract labor, expressed through the common form of money. No convenient standard scale governs this reduction. Marx tells us “this process appears to be an abstraction; but it is an abstraction which takes place daily in the social process of production.”66 The means by which the reduction occurs is a social negotiation that takes the form of the mobility of labor between branches, or labor competition in other words. In single-factor economies (such as among precapitalist artisanal producers, who are both owners and laborers), the reduction process takes the form of an equitable negotiation: artisans in one industry who are routinely underpaid for their concrete efforts will over time retrain and retool in an industry where the product of their labor is more valued. In such largely hypothetical economies, this is also the means by which an equilibrium price for goods is arrived at, since goods of equal price will tend to represent equal quantities of homogenous, socially necessary labor time, and any disequilibrium will lead to an incentive for artisans to move into new branches. In a multifactorial mode of production like developed capitalism, the mechanism by which an equilibrium price is reached is quite different, but the process of wage equalization via the movement of labor between branches remains relatively similar.67

Abstracted to a purely theoretical point of view, there is no necessary inequality in the rate of reward for skilled and unskilled work in capitalism, aside from transient disequilibria.68 The difference in wages accurately reflects the larger mass of abstract labor that skilled work generally contributes to production, which is in turn allowed by a real difference in reproduction cost, and in things like education and training.69 But this equality is quickly revealed to be a kind of cruel joke when we consider concrete social and political factors which might distort the reduction process. Capitalism contains within it a tendency towards the separation of physical and intellectual functions within the workplace, and this divide is entrenched by the practice of giving skilled intellectual workers the additional task of enacting workplace discipline on behalf of the capitalist. Barriers to education and labor mobility sometimes limit the ability for workers to gain skills, contributing to a scarcity of skilled workers. All of this contributes to a potential for additional socio-political power among skilled workers. By joining together into craft unions and professionals’ associations which exclude the mass of unskilled workers, skilled workers can use this power to drive up the value of their labor even higher by demanding tightened entry requirements into their profession, restrictions on the employment of migrant labor, or subsidized training for their fellow members. Some of these demands also change the general organization of social production and therefore the value contributed by labor power (the change results in an increase in both variable capital advanced and surplus value contributed). But in some circumstances, organized workers can also simply demand an increase in wages with no corresponding change in the organization of production (the capitalist must increase his variable capital cost with no corresponding rise in surplus value) – this is what Emmanuel meant by an “exogenous” wage increase. Such an increase is at first directly against the economic interests of capitalists, and so only some political force external to production can facilitate it.

Now possessing income beyond its pure cost of reproduction, skilled workers could put their money towards things previously reserved for the bourgeoisie alone. They could purchase wage goods in great quantity or of great quality.70 Or they could attempt to find opportunities for profitable investment and begin the long, slow climb towards entry into the stable propertied classes. But this was a risky undertaking, and many such workers could find themselves indebted or otherwise impoverished and thrust back into the lower orders. In the 19th century, skilled work was still highly precarious, involving considerable risk of unemployment, and while wages were high relative to the general wage they were still nothing compared to petty-bourgeois incomes. Despite all this, skilled workers left the workforce to become shopkeepers and administrators often enough that many craft unions had special rules to accommodate them as members.71 The aristocratization of workers has always led to some form of economic embourgeoisement, the acquisition of elements of a bourgeois class position such as profit income, but it isn’t synonymous with it. The ease by which investments could be made on skilled worker salaries has varied with time. In the present day some extremely high-income worker aristocrats gain no obvious profits (some 15.01% of the top US quintile), and sometimes very low-income individuals immiserate themselves in order to invest, aspiring to become the pettiest of the petty-bourgeoisie (some 21.8% of the bottom quintile).72 Class position is more complex than income, and one’s dependence or independence from labor markets is affected by other factors, but there is nonetheless a considerable overlap between workers with high wages and those who invest.

This is the source of the tendency for labor aristocracies to begin to merge into the petty-bourgeoisie, as their consciousness begins to shift in anticipation of entry into this class. Moreover, it begins to be exploited as if it were petty bourgeois (ie. by being squeezed by larger capitals, taxes, finance etc) and reorients itself away from the class struggle in the workplace to fight against the haute-bourgeoisie on other fronts. This is also the source of the ‘self-negating’ aspect of aristocratisation. As high wages intensify and more workers are able to invest, the basic political functions of the labor bureaucracy become more difficult. Workers leave the unions and stop voting for the bourgeois-labor parties. More and more of the class begins to see itself as petty-bourgeois, whether or not it has wholly become petty-bourgeois in its economic life.

We have seen that the bourgeois-labor parties no longer use the most explicit pro-colonial or pro-imperialist language, but it should be remembered that in the lead up to the First World War such words had progressive connotations, being associated with uplifting colonised peoples and improving conditions in the metropole. It was only after the First World War that these connotations were wholly lost, and a new language of progressive imperialism began to form, based on the responsible management of the colonies and their transition to democratic members of the global community. This too would be a little paternalistic for modern tastes, and the language has shifted again to maintaining the level of force necessary to uphold global ‘humanitarian commitments.’ However, each change in language has not resulted in any real change in the political alignment of the bourgeois-labor parties, union bureaucracy, or labor aristocracy in general. In times of war and crisis they are still in lock-step with their respective states, as the Ukraine war demonstrates very well: the British Trades Union Congress, Canadian Labour Congress, and US AFL-CIO have all supported actions taken by their countries against Russia.

The labor aristocracy is tied to the interests of its national bourgeoisie via the labor bureaucracy, which is itself integrated into the machinery of state via the bourgeois-labor parties.73 It is tied on another level via the more general benefits it hopes to receive from participation in imperialism or national oppression. In a crisis, it is sometimes aligned directly with its employers, such as in the case of workers facing job losses and fighting for their sector to be saved.74 The attitude of a national-capital bloc towards the rest of the world, and of the labor aristocracy to which it is tied within national politics, tends to reflect its position in the world-system. The Russian bloc, for example, is currently in a position of extreme precarity, on the verge of entering the periphery, and bears a more desperate attitude, while the US bloc is in a safe but potentially declining hegemonic position, more concerned with managing the situation and taking proactive steps to end a potential rivalry before it can even begin. As a result of their integration into the state, the politics of both labor aristocracies reflect this general world position held by their national capitals – the Russian “progressive” leaders, aside from a few Duma representatives who can be counted on one hand, are in full support of the Ukraine war, while in the US the most that is being demanded are minor course corrections in the management of empire, so that a few more dollars can be put towards social services.

Aside from these examples in the imperialist countries, it should also be noted that it’s conceivable for something quite like a labor aristocracy (which we might call a worker elite) to exist in quite different countries. These include non-imperialist countries with significant national oppression or patronage networks, but in such cases, there would still be a tie between the worker elite and a national bourgeois regime as its protector or class patron. The tie between both kinds of elevated strata and national bourgeois geopolitical interests is very strong, regardless of whether these interests are best advanced through imperialist means.75 This helps explain the presence of labor aristocratic ideas and bourgeois-labor parties even in very poor countries, whether or not there is a high-waged labor aristocracy per se. In such cases, these parties are usually lacking in local support unless there is an additional factor such as the domination of the unions by one ethnic group, backing from imperialists, or privileged workers in one sector of the economy. As we have seen, imperialism is not a strict prerequisite for the elevated position of some workers, but it is the imperialist countries that have developed powerful and especially high-waged labor aristocracies.

So there are at least three proximities to consider when analyzing the class position of the labor aristocracy. These are:

- An essentially working-class position, as well as factors that make its position precarious, leading to a proximity to the proletariat.

- The connection between high wages and the ability to invest, leads to a proximity to the petty-bourgeoisie in anticipation of entry into this class.

- A proximity to the dominant elements of the haute-bourgeoisie on matters of nationality, foreign trade, immigration, war etc, which represent either a shared opportunity for advancement or a potential competitive threat depending on the position in the world-system.

In other words, the labor aristocracy is in a complex class position, split in at least three directions. This can help explain the considerable diversity of labor aristocratic politics, which nonetheless cohere to a general pattern. In stable times, the ability of high-waged workers to gain profitable investments is improved, embourgeoisement is accelerated and the politics of the labor aristocracy can become virtually indistinguishable from those of the petty-bourgeoisie, albeit with a certain workerist flavor, as its consciousness anticipates its eventual entry into this class. In unstable times the labor aristocracy begins to lose its position and anticipates its reabsorption into the lower strata of the working class. Depending on the strength of various other factors, like the strength of local progressive forces, national oppression, or foreign imperialism, the declining labor aristocracy may align with a more proletarian politics, or with the semi-independent political forces of a declining petty-bourgeoisie, ie. with fascism or conservatism. In times of war or national crisis, its politics parallels that of the dominant capitalists in its country, although amidst the immiseration of a truly existential war this might be outweighed by other aspects of its class position. So long as it has an independent political life the labor aristocracy won’t make many real sacrifices for the “good of the nation” in the abstract.

No matter how much conditions act to pull the labor aristocracy away from the rest of the working class, a limited kind of workers’ consciousness remains. There is a willingness to fight for minor reforms in favor of the class (exclusively within national borders), and some interest in unionization (usually out of a desire to gain leadership positions and invest those positions with supporters). This residual working-class politics is usually distorted by economism and spontaneism. There is an unwillingness to go beyond demands for wage increases, and sometimes great stock is placed in the self-leadership of the class. By this it is meant that tailist politics should be the norm, as workers come out of the womb with correct ideas. If pushed, such as when a more genuine proletarian politics is on the rise, the leadership of the labor aristocracy can adopt some really quite advanced leftist-sounding policies and organizational forms (the most pure expression of which is entry into a party of the whole class), but usually only as an act of political judo to win support from subjective revolutionaries. This is the point at which the labor aristocracy is at its most powerful: when there is a credible alternative leadership of the working class, that is to say when a genuine class consciousness is at its height, so too is the distorting effect of aristocratic ideas, as part of the larger forces of reaction.

1.3.1: On ‘objective interests’

What are the precise interests of the aristocratized workers, considered from an objective standpoint? What are their ‘material interests’ dictated by “in the last instance?” To answer this question at all it’s necessary to understand that ‘interests’ are not so simple: as I stated earlier, precise quantifiable interests are not always a significant factor in events, being important only where actors are relatively conscious of these interests, and where different interests are qualitatively comparable (such as in the case of a bourgeois assessing which path maximizes profit), otherwise the interactions between contradictory interests take on new levels of complexity, and certain ingrained mystifying notions or habits can be just as significant.76

Objective interests also change drastically depending on the length of time and social scale that is being considered. Considered from the extreme ends of these scales (where we can find interests that are no less ‘material’), there is an astonishing unity of interest among all people. For example, if by objective interests we mean the interests of the whole species, considered across all known history, then there exists a shared interest in communism, in the end of all forms of domination, self-destruction, and division, so as to exit the predatory phase of human development and the tendency towards collective annihilation it brings. Conversely from the perspective of individuals stripped of all social context, considered in only the most immediate terms, every person has an overwhelming interest in extending the terms of their own survival, disregarding any high-minded purpose beyond this.77 Neither of these extremes manifests in consciousness outside of exceptional circumstances (the highest stages of revolution, or lowest depths of misery, respectively). To strongly affect consciousness, an interest usually needs to be counterposed to its opposite, in political life.

Among people considered in terms of their own times, and identified with limited groupings (class, nation, faith), there exists this counterposition. If we narrow down what we mean to just the interests of different class strata in political life in the core, then the interests of the labor aristocracy are still anything but simple: its contradictory position means that it bears both an interest in the maintenance of imperialist divisions in living standards, and an entirely incompatible interest in the victory of its class as an international whole. Aristocratized workers are not constantly weighing up one set of interests against the other at any given time, using some objective numeraire; their class position tends to promote ideological mystification, and besides the kinds of benefits that can be derived from revolution or collaborationism are incomparable in their own terms (the maximization of wages is impossible to compare to their ultimate abolition). Insofar as such objective interests have any historical impact it’s only as one of several determinants, and even then only through the mediating factors of narratives and ideas. If interests are generally expressed through mystifying proxies in class societies, then the exception is the class-conscious element, such as combat organizations of the international working class, whose ideas should gradually develop through practice to quite accurately and directly reflect a set of objective class interests.

If instead what we mean by objective labor aristocratic interests is what interests will ‘win-out’ of their own accord, in the fullness of time, then this too is misleading. It still assumes a kind of algebraic combination that, when all the appropriate subtractions are made, would leave only the ‘strongest’ set of interests.78 But since different sets of class interests are qualitatively incomparable (they are not reducible to something so simple as how to maximize individual appropriation of the social surplus), no such mathematical equation exists. Qualitatively different interests instead cancel each other out in a more complex and uneven way. Left alone, there is no rule that one set of interests should win out; and it is more likely that some mystificatory mish-mash of ideas will allow both to be reconciled to some degree. The labor aristocracy as a whole won’t tend towards any independent clarification of its interests one way or the other, without some major change in conditions, or the intervention of the conscious element. Once brought to the point of crisis, however, historical experience seems to suggest that the ultimate deciding factor for strata caught between revolution and reaction is the question of who is likely to win.

- I would like to thank Elle Brocherie and Rob Ashlar for their helpful suggestions and patience as proofreaders.

- Eric Hobsbawm, Worlds of Labour: Further Studies in the History of Labour (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1984), pp. 214–215; Robert Quentin Gray, The Aristocracy of Labour in Nineteenth-Century Britain (London: Macmillan, 1981), pp. 8–10; John Field, “British Historians and the Concept of the Labor Aristocracy” Radical History Review 19 (Winter 1968–69): pp. 62–65.

- John Foster, “The Aristocracy of Labour and Working-Class Consciousness Revisited” Labour History Review 75, no. 3 (2010): p. 246.

- Bakunin paints Marx as the leader of this aristocracy! Mikhail Bakunin, “On the International Workingmen’s Association and Karl Marx” MIA, 1872. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/bakunin/works/1872/karl-marx.htm; There are earlier examples of DeLeon’s use of the phrase, but here he uses it to describe the AFL. Daniel DeLeon, “Nothing Peculiar About it,” Daily People 8, no. 297 (April 1908), http://www.slp.org/pdf/de_leon/eds1908/apr22_1908.pdf/

- Eric Hobsbawm, “Lenin and the ‘Aristocracy of Labor’” Monthly Review, 1 December 2021. https://monthlyreview.org/2012/12/01/lenin-and-the-aristocracy-of-labor/.

- Friedrich Engels, “Engels To Hermann Schlüter” MIA, 1892. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1892/letters/92_03_30.htm.

- Foster, “The Aristocracy of Labour,” p. 246

- “The bourgeoisie of an imperialist “Great” Power can economically bribe the upper strata of “its” workers by spending on this a hundred million or so francs a year, for its superprofits most likely amount to about a thousand million.” Vladimir Lenin, “Imperialism and the split in socialism.” MIA, October 1916. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/oct/x01.htm.

- Vladimir Lenin, “The Second Congress of the Communist International.” MIA, July-August 1920. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1920/jul/x03.htm; quoted in Max Elbaum and Robert Seltzer, “The Labor Aristocracy: The Material Basis for Opportunism in the Labor Movement” (Working paper, Line of March, May 1982–April 1983), p. 15, https://www.marxists.org/history/erol/ncm-7/lom-labor-imperialism.pdf.

- Elbaum and Seltzer, “The Labor Aristocracy.” p. 16

- A term Lenin adopted, like much of his new jargon during the split in socialism, from the DeLeonists. Ibid.

- Lenin, “Imperialism and the split”; quoted in Hobsbawm. “Lenin.”

- Ibid.

- Perhaps he reasoned that later Marxists, ones not suffering from a “shortage of French and English literature and from a serious dearth of Russian literature” in a Zurich library, would bring his preliminary gestures towards this or that factor closer to the concrete reality. Unfortunately, this was rarely attempted. Vladimir Lenin, Imperialism: the highest stage of capitalism, MIA, April 1917, preface. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/imp-hsc/pref01.htm.

- This is sometimes described as the Second International’s belief in “false consciousness” as an explanation for incorrect theory, but this term was really not in widespread use until its popularisation by Lukacs and Marcuse. More common was simply accusing opponents of affinity with the petty bourgeoisie etc.

- Arghiri Emmanuel, “The Multinational corporations and inequality of development” UNESCO International Social Science Journal 28, no. 4 (1976): p. 761. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000019907?posInSet=7&queryId=5f2e1e1c-594d-4b02-a67f-6af3a98b8094

- Pim de Zwart, Bas van Leeuwen, and Jieli van Leeuwen-Li, “Real wages since 1820” In How Was Life? Global Well-being since 1820 eds. Jan Luiten van Zanden, et al. (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2014), p. 80.

- Arghiri Emmanuel. Profit and Crises (London: Heinemann, 1984), pp. 17–20.

- Max Roser and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, “Literacy” Our World In Data, 20 September 2018. https://ourworldindata.org/literacy#.

- This was a point of contention between Hobsbawm and EP Thompson, who showed that many of the arguments around labor aristocracy existed in England before the 1850s. But the specific point at which artisans transformed themselves into skilled wage laborers is rather difficult to pinpoint, and not all that important for our purposes. Hobsbawm, Worlds of Labour, p. 217.

- This is of course one of the central claims of Eric Blanc’s work in support of the Bolsheviks as something close to a ‘party of the whole class’ since the advanced Latvians did not expel their Menshevik section. One wonders whether the Menshevik section would have supported the revolution were it not for the Bolshevik nationalities policy, which acted to tie certain petty-bourgeois sections to the party. Indeed Blanc’s strongest arguments apply exclusively to national minorities. Eric Blanc, “Socialists Should Take the Right Lessons From the Russian Revolution” Jacobin, 20 July 2021. https://jacobin.com/2021/07/democratic-socialism-russian-revolution-leninism-workers-movements.

- From Hanna Batatu, The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq: A Study of Iraq’s Old Landed and Commercial Classes and of its Communists, Ba‘thists and Free Officers (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978), only the good lord knows which of the 1300 pages this was on, I’m afraid.

- Where significant chunks of the upper strata of the workers and lower strata of the petty-bourgeoisie were easily won-over to revolution, there were usually additional factors that threatened their position, or constrained the completion of the bourgeois programme. Factors like autocracy, national oppression, imperialism, wartime hardship and defeat etc. This is true in all of the above examples.

- Karl Marx, “Marx to Sigfrid Meyer and August Vogt In New York” MIA, April 1870, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1870/letters/70_04_09.htm.

- In Britain, general unionism is altogether different, and historically parallelled the development of radical industrial unionism elsewhere from the 1890s. Hence readers familiar with the British unions may find my discussion of general unionism less applicable. However, the development of business unionism eventually produced much of the same results nearly everywhere. For a history of British general unionism see Eric Hobsbawm, Labouring Men: Studies in the History of Labour (New York: Anchor Books, 1967), pp. 211–240.

- Most of this paragraph is drawn from Fritjof Tichelman, “Socialist ‘Internationalism’ and the Colonial World: Practical Colonial Policies of Social Democracy in Western Europe before 1940 with Particular Reference to the Dutch SDAP,” in Internationalism in the Labour Movement, 1830–1940, eds. Frits Van Holthoon and Marcel van der Linden (Leiden: Brill, 1998), pp. 87–109; cited in Zak Cope, The Wealth of (Some) Nations (London: Pluto Press, 2019).

- Charles Post, “The Myth of a Labor Aristocracy.” MIA, July 2006. https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/atc/128.html#n33.