Stephen Tumino reacts to the new and supposedly final installment of long-running horror-slasher film franchise ‘Halloween’ with an analysis of the franchise’s trajectory, arguing that the thrust of ideological demystification found in John Carpenter’s original has been replaced by a thematic which obscures the reality of contemporary capitalism.

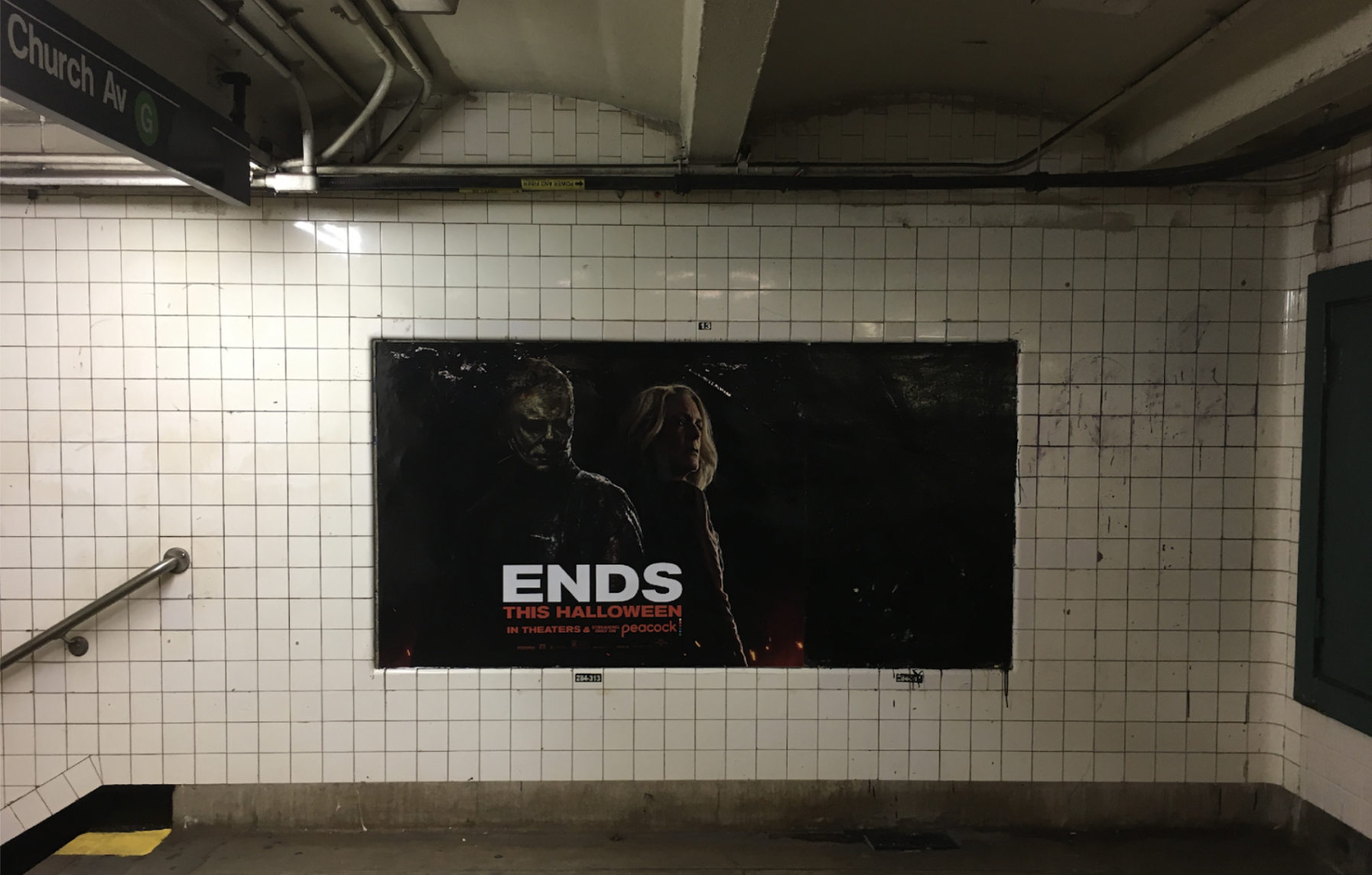

Halloween, both the annual holiday and the endless horror film franchise that bears its name, has a basically conservative function. Both make it appear that, despite disruptive changes in the shape of things, social life remains basically the same. In their ritual repetition of the familiar formulaic devices of horror they alienate phenomenal effects from their underlying cause in class relations and prevent the emergence of the transformative knowledge workers need to end their dehumanization as alienated labor exploited for profit. Halloween Ends, the latest installment in the rebooted franchise scheduled for release this halloween season, has the dubious distinction of being both a nostalgic repetition of the original slasher film and a familiar way to mark the holiday. Both cash in on a popular desire to “return to normal” and bury what the pandemic has revealed; the genocidal necronomics of a social order that puts the profits of a few before the needs of the many.

What halloween does, in all its cultural iterations, is translate the social anxieties caused by the systemic violence of class relations into the familiar idioms of everyday violence, which have the appearance of being the random and irrational acts of individuals. Halloween is capitalism with a spooky mask that makes it seem as if the daily horror of wage labor/capital relations may be conjured away by communing with “otherness.” The carnivalesque embrace of otherness and the plastic imitation of social solidarity these familiar cultural celebrations promise represent the “phantom objectivity” that animates the “ghost dance” of commodities that Marx dissects in Capital as masking the abstract social labor exploited in their production.1 Halloween Kills, last year’s installment in the franchise, performs this alienation of labor masked as spirit by making The Shape (the “boogey-man” in the guise of Michael Myers) a product of people’s irrational fears run amok because “the system failed” them, as Laurie Strode, the “final girl” of the slasher franchise, roars to the audience. By “tak[ing] on what happens when trauma infects an entire community,”2 according to Jamie Lee Curtis who reprises her role as Laurie, the film is an attempt at a socially relevant horror film that will make sense of the lurching horror of dying neoliberal capitalism—leaving the world as it came in, “dripping from head to toe, from every pore, with blood and dirt,” as Marx observed—by retconning the slasher film genre formula that John Carpenter’s original Halloween established in the late seventies as a coded warning about the then looming evils of neoliberalism.

However, John Carpenter’s Halloween disguised the social evils associated with neoliberal budget slashing, like the gutting of state run mental facilities that would swell the ranks of the houseless, as a slasher film about a sadistic killer escaped from Smith’s Grove Sanitarium “going home” to the suburbs of Haddonfield, Illinois to slaughter frisky teenagers. Using what would become the slasher film code of Halloween‘s many imitators, Michael’s rampage is represented as a story of good vs. evil, as he robotically hacks his way toward the final girl whose virginal innocence represents the “heart” of the small town America which birthed this particular monster of toxic masculinity. Halloween, however, is what literary critic Tzvetan Todorov calls a “fantastic” story, as it remains uncertain in the film if the terror The Shape unleashes on the neighborhoods of Haddonfield has a “natural” explanation in the traumatic childhood of Michael Myers and the failure of the state to treat or stop him, or, instead, a “supernatural” one about “pure evil” that is finally impossible to fathom or prevent.3

As a film that returns to the past of horror—just compare the famous five minute opening Panaglide shot of six year old Michael approaching his sister Judith, whom he will kill before her bedroom mirror, with H. P. Lovecraft’s short story “The Outsider,” of which Carpenter is an outspoken enthusiastic fan4—it uses such tropes as “pure evil” to characterize Michael’s murderous rampage, whose inability to be killed represents a “supernatural” element in the story. As a “new” form of horror film for the late 70s, however, it also implies that the horrific events may have a psycho-sociological cause lying in the personal traumas and social alienation of young “middle class” men. Michael, in the form of what the credits call The Shape, is a textual figure of this Derridean “undecidability.” In other words, he is the spectral presence of the filmic absence of any reliable knowledge of the real cause of horror lying in class relations. His murderous rampage therefore represents an attack on the sure sense of the “proper”(ty) of small town American life, itself the creation of the post-war boom sustained by New Deal policies since the 50s, and which was coming to an end with the neoliberal deregulatory frenzy of the 80s. Much like Carpenter’s They Live, a Hollywood “masterpiece” for affirmative leftists such as Žižek, the original Halloween represents a cultural critique of “Reaganomics” for destroying the sense of community that boomers tend to associate with social democratic forms of bourgeois rule.5 In its fantastically bifurcated narrative structure the film suggests that the biopolitics of the slasher film, like the cultural politics of neoliberalism, with its deep investment in moralizing about the sex lives of children, gender dynamics, and cultural differences, is a diversion from the political forces that shaped small town America that have since weirdly turned, like a rotting pumpkin, to destroy it.

As an escaped mental patient cum spree killer Michael Myers reinforces “middle class” fears that budget cutting, “tough on crime” politicians use to justify the transfer of social wealth from the workers to the owners by slashing government health services and investing in militarizing the police to manage the resulting social disruptions. As The Shape of “pure evil,” however, Michael represents something more abstract, which Marx in Capital Vol. 1 explains as the dominance of the “value-form” over social life, which as “dead labor” he describes as the dominant, automatic, and self-valorizing Subject of the process of capitalist production. The full-spectrum dominance of capital as “dead labor” over “living labor” is evidenced in the original Halloween by having even the social democratic agents of the welfare-state like Dr. Loomis, who are tasked with caring for the victims of capital’s manufactured health crisis, demonize them instead by targeting Michael as “pure evil” and stoking “boogey-man” illusions among the suburbanites about the houseless disabled coming home to seek revenge. The police too are represented as incompetent and unable to stop Michael and Dr. Loomis must become a vigilante, assuming police powers outside the law to stop the evil, Dirty Harry-style. The film, in short, is a dark carnivalesque spectacle of the social fallout of neoliberal deregulation that gestures toward some vague notion of authoritarian social democracy as a solution, only to have it too fail to stop the evil as Loomis’ final barrage of bullets has no effect on Michael’s endless revivals.

The politics of the original Halloween reveal the complicity of reformist cultural criticism in normalizing class relations which alone explain why the living standards of Americans have so precipitously declined since the 70s. It was not venal and corrupt elites unleashing the mentally disabled on the suburbs and turning the suburbs against the poor and marginalized that destroyed the “middle class,” but the rising productivity of workers causing the falling rate of profit. As Marx explains, because in the context of market competition between private firms technological innovation is rewarded as it serves to lowers the costs of production and increases market share, it also in the long term tends to increase overall the “constant capital” invested in the means of production relative to the “variable capital” expended on the wages of workers whose labor alone is the source of value. The result is that less labor is required on average to produce more goods, which depresses wages, increases the ranks of the unemployed, and lowers the rate of profit overall. Horror makes visceral the barbarism of capitalism in decline which is normally hidden behind a glossy and glamorous facade, but in its invocation of the other-wordly it also occults its economic cause in the class structure and the exploitation of labor by capital.

Whereas the original Halloween allegorizes the politics of social evils like the health care crisis and government capture by capital through its use of slasher horror tropes, Halloween Kills uses cultural signifiers as a mask that hides an ontological horror that exceeds social explanation. To put it another way, the original Halloween used the supernatural as a metaphor for the purpose of ideological demystification of neoliberal culture, but Halloween Kills spiritualizes evil to defamiliarize its audience from a class based explanation of their immiserated lives. It does so under the guise of subverting the code of the slasher film, breaking with the trope of the evil killer drawn to the virginal innocence of the final girl by emphasizing that The Shape is not after Laurie Strode, as Dr. Loomis believed, but literally just wants to return “home” to stare at his own reflection in his murdered sister’s old bedroom window. The Shape in this way conforms to Lacan’s early definition of the “real” as “that which always returns to the same place.” This “real,” he suggested, was the imaginary of a primarily narcissistic subjectivity fixated on its own idealized image in the mirror-stage so as to avoid confronting the unimaginable Real as a non-symbolizable excess that eludes sense making. But, it is horror as a Kantian “thing-in-itself,” a Real but non-intelligible excess that defies social explanation and therefore transformation, that is ultimately being advanced by Halloween Kills beneath the guise of a retconned reboot of the outdated slasher genre.

On the surface, Halloween Kills is “uncanny” in Todorov’s sense in how it signals a social allegorical message by giving a “natural” explanation of “evil” as an expression of communal fears about cultural others. The now more than middle-aged children of Haddonfield are shown to be narcissistically attached to the “boogey-man” story about Michael Myers they were told in their youth as a way to justify why their lives have gone nowhere. Like Laurie herself, they have come to define themselves as fatefully destined to finally put down the evil that has stunted their lives. Only after they scapegoat another escaped mental patient they mistake for Michael, whom they drive to his death while chanting “evil dies tonight,” does Laurie learn the lesson that “every time somebody’s afraid, the boogey-man wins.” In other words, any attempt to overcome evil through social organization is itself monstrous in making people believe in a source of evil. Evil is just a label humans put on nonhuman reality that is in itself “wholly other” and unknowable. In this way Halloween Kills suggests, as McKenzie Wark imagines, that capital is a “myth” of Marxist critique and that “the hidden abode of production” that explains the social for Marx must be dismissed, as Bruno Latour does, as the “fetishism” of “causal explanations coming out of the deep dark below.”6

The difference between the original Halloween and its reboot today is not just only in how they use horror to represent the real—whether as tropic and symptomatic of cultural conflicts in the original or as something real in itself that eludes sense making in the latest iteration—but also an indication of the delegitimation and recuperation of bourgeois ideology in the wake of the historic decline in profitability. Halloween was originally produced at a time when the task of bourgeois ideologists was to “deconstruct” mimetic epistemologies as “totalitarian” restrictions on the “pleasures” to be had in the appreciation of “differences” and the valorization of the “marginal,” as in the writings of Derrida, Foucault, and Lyotard, which have since been revealed to have been supported by the CIA and complicit with the global project of neoliberal restructuring.7 Halloween‘s “fantastic” uncertainty about the cause of “evil” is an example of the popularization of postmodern ideas that served to normalize the flexible labor markets required by high-tech global capitalism in its mission to deregulate the economies of the socialist bloc countries. The reboot of Halloween in 2018, by contrast, reflects the newer legitimation of capital today found in the writings of the “new materialists,” such as Bruno Latour, Graham Harman, and Jane Bennett, who, despite their differences, all argue for a post-critique-al concept of the “real” as beyond the social and resistant toward all cultural epistemologies. The shift is due to the fact that the task of capital today is to somehow prove to an immiserated and discontented populace that it remains the only realistic means to address the climate crisis, increasing inequality, and rising extremism. The new materialists posit that the recognition of the real as beyond culture is the litmus test of ethics today, providing the model for how we should address the crisis of capitalism by embracing otherness. In the contemporary commonsense, itself constructed from ideas produced by the (post)humanities and circulated in the popular culture by such films as Halloween Kills, this means that Michael Myers must be represented as wholly other and an object lesson on the dangers of mass politics, to rally the people to a “higher” cause—getting back to “normal” working to make profits for the owners.

The franchise also suggests a more vulgar reason for its ontological turn in the previous Halloween reboot of 2018, of which Halloween Kills is the second part of a proposed trilogy, to be completed (really?) with Halloween Ends this halloween season—profit. In the Halloween reboot, when Laurie’s granddaughter is discussing the legacy of Michael Myers with her friends, they can only wonder at why, given that “there’s a lot worse stuff happening today,” the town is so obsessed with “one guy with a knife that killed a couple of people” forty years ago. This of course acknowledges the attitudes of today’s audience who are expected to find cathartic experience in a horror movie about a serial killer from the 70s while they daily confront the global horrors unleashed by what Lenin called the final “moribund” stage of capitalism: climate destruction, rolling pandemics, global nuclear war and total economic collapse.8 The filmmakers finally give a cynical take on this by telling contemporary audiences that evil as they know it is only a cultural construct behind which is the cosmic evil of eternally recurring natural forces that exceed causal social explanation. The deathless return of The Shape, in short, must not be explained, as to do so would not only perpetuate the evil that men do—label so as to master the other—but also kill the gold bearing goose.

Halloween Kills is a posthumanist film that cashes in on the dominant ideology of the post-neoliberal moment expressed in the terms of high philosophy as “new materialism,” “weird” and “speculative realism,” “object-oriented ontology,” and the like, that makes materialism synonymous with embracing the other-worldly and rejecting materialism as “the silent compulsion of economic relations.”9 In the “new” materialism(s) class based explanations of the cultural real are made out to be a variant of anthropocentric speciesism that is taken to be the driver of climate catastrophe, as if our profit driven global disasters were the result of the intellectual hubris of cultural elites rather than the supremacy of capital over labor. In this posthumanist ideology, what is truly “radical” is not entering into class conscious struggle to transform capitalism into socialism by connecting its surface effects with their underlying cause in the exploitation of labor for profit, but rather imagining a “world without us” by speculating on the “thought of the unthinkable” as the antidote to “capitalist realism” because the struggle to end capitalism is too “impossible” to imagine and, besides, “capital is dead” anyway.10

- Marx’s phrase in German is “gespenstige Gegenständlichkeit” (“ghostly” or “spooky objectivity”), which the Penguin edition translates as, “phantom-like objectivity”. In the French edition, Marx’s last revision, the phrase is “réalité fantômatique” (ghostly reality). In the Marx-Engels Collected Works it is “unsubstantial reality” (Moscow: Progress Publishers, Vol. 35, 48). “Ghost dance” (Capital Vol. III, Chapt. 48), is variously translated as “ghost-walking” (MECW), “haunting” (Penguin), or “danse macabre” (French).

- Jamie Lee Curtis Spills Details on New ‘Halloween’ Film, video, 1:33, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EjvI5rBlfbA&t=3s&ab_channel=SiriusXM.

- Tzvetan Todorov, The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre (Ithaca: Cornel UP, 1975).

- John Carpenter, “The Guardian Interview,” London, 29 July 1994, video, 48:31, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V2dHtZMpcJA&ab_channel=Lucas.

- Slavoj Žižek on “They Live” (The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology), video, 00:54, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TVwKjGbz60k&ab_channel=ChristianG.

- McKenzie Wark, Capital Is Dead: Is This Something Worse? (New York: Verso, 2021), 24; Karl Marx, Capital. A Critique of Political Economy. Volume I, Karl Marx, Frederick Engels: Collected Works 35 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1983), 186; Bruno Latour, “Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern.” Critical Inquiry (Winter 30, 2004), 229.

- Gabriel Rockhill, “The CIA Reads French Theory: On the Intellectual Labor of Dismantling the Cultural Left,” The Philosophical Salon (28 Feb 2017). https://thephilosophicalsalon.com/the-cia-reads-french-theory-on-the-intellectual-labor-of-dismantling-the-cultural-left/; Daniel Zamora and Michael C. Behrent, Foucault and Neoliberalism (Cambridge: Polity, 2015).

- V.I. Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. A Popular Outline, V.I. Lenin Collected Works 22 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1974), 302. http://marx2mao.com/PDFs/Lenin%20CW-Vol.%2022.pdf.

- Marx, Capital, 726.

- Eugene Thacker, In the Dust of This Planet: Horror of Philosophy, Volume 1 (Winchester and Washington: Zero Books, 2011), 2; Wark, Capital Is Dead.