Parker McQueeney lays out the case for building a party around a minimum-maximum program. Reading: Cliff Connolly.

Every party pursues definite aims, whether it be a party of landowners or capitalists, on the one hand, or a party of workers or peasants, on the other… If it be a party of capitalists and factory owners, it will have its own aims: to procure cheap labour, to keep the workers well in hand, to find customers to toil harder—but, above all, so to arrange matters that the workers will have no tendency to allow their thoughts to turn towards ideas of a new social order; let the workers think that there always have been masters and always will be masters… The programme is for every party a matter of supreme importance. From the programme we can always learn what interests the party represents.

—Nikolai Bukharin and Yevgeni Preobrazhensky,

The ABC of Communism, 1920

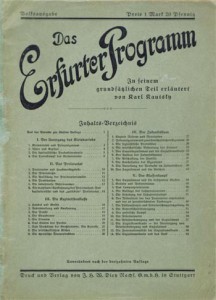

In the Autumn of 1891, Germany’s socialist party—the Social Democratic Party of Germany, or SPD—had only the world to win. Just one year prior, the party’s chief prosecutor and preeminent tyrant of the European continent, Otto von Bismarck, was forced to resign. The Reichstag refused to renew Bismarck’s Anti-Socialist laws, which had shut down dozens of newspapers, trade unions, and socialist meetings. This all happened within the span of a month. It is safe to say that when the party met for its Congress in Erfurt, they were bolstered in a manner that European socialists had not been since the rise of the Paris Commune twenty years before. The Erfurt Program is notable for a myriad of reasons, not least of which includes the declaration that:

The German Social Democratic Party… fights for the abolition of class rule and of classes themselves, for equal rights and equal obligations for all, without distinction of sex or birth… it fights not only the exploitation and oppression of wage earners in society today, but every manner of exploitation and oppression, whether directed against a class, party, sex, or race.1

The Erfurt Program asserted, as Marx had, that socialists must fight for democratic rights within bourgeois society. With historical hindsight, it seems clear enough that capitalism cannot be abolished via a socialist party simply winning elections in a bourgeois government. In Bolivarian Venezuela, Mitterand’s France, and Tsipras’s Greece, the governing socialist parties were able to sit behind the wheel of a liberal democracy, yet none of these countries were able to meaningfully disrupt capitalism. This does not mean that basic bourgeois-democratic rights have no use to even the most revolutionary of socialists; the SPD learned under Bismarck that universal suffrage, the right to free assembly, the ability to form unions, and the abolition of censorship are all helpful to a proletariat undergoing a transformation into a “class-for-itself”. Although winning these reforms are not the first step on the path to socialism, they do clear debris that blocks the entrance. “If all the 10 demands were granted,” Friedrich Engels speculated in his critique of the Erfurt Program draft, “we should indeed have more diverse means of achieving our main political aim, but the aim itself would in no [way] have been achieved.”2

The more lasting legacy the Erfurt Program had on socialist thought was in its popularization of the minimum and maximum program—though these were abstracted from Karl Marx and Jules Guesde in their program for the French Workers’ Party, eleven years prior.3Since Erfurt, the program has been the focal point for every party of the class. As Bukharin and Preobrazhensky argue in The ABC of Communism, “The programme is for every party a matter of supreme importance. From the programme we can always learn what interests the party represents.”4 Theoretically, the minimum program, which was the party’s reform platform, would win over a mass base of workers by improving their immediate conditions. When enacted in full, it would give the party the necessary mandate and class power to enable its maximum program, or the revolutionary measures required to actually eradicate the dictatorship of capital and begin the process of developing a socialist mode of production. In reality, the SPD—along with the other parties of the Second International—eschewed their maximum programs as they became gradually more entrenched into the bourgeois constitutional order. Whether in the trade union bureaucracy, the universities, or the Reichstag, the Second International’s loyalty to the capitalist state and nation eventually led the majority of its parties to abandon internationalism by siding with their respective home countries during the outbreak of World War I. It is a tragedy often lamented on the Left.

Although the term amounts to welfare state liberalism today, the social democrats of Erfurt were largely Marxists. Nevertheless, as a nominally social democratic movement appears to be re-emerging onto American politics for the first time in the life of many of its participants, what can contemporary socialists in the United States learn from the original social democrats? In many ways, the US Left is in a similar position that German social democrats found themselves in around the time of the Erfurt Congress. Both had recently come out with some unthinkable—at least to the ruling class—victories after decades of suppression and neither had ever meaningfully seen power. More importantly, the 1891 SPD and the 2018 American Left share a common primary task: the consolidation of workers into a class-for-ourselves, cognizant of our common condition and interests.

What were the minimum demands of the Erfurt Program? The first seven dealt exclusively with securing and expanding democratic-republican rights. Perhaps shockingly, many of their demands would still be progressive gains 127 years later: legal holidays on election days, ending voter suppression, popular militias in place of standing armies, free meals for school children, gender equality in the legal sphere, elected judges, and the end of capital punishment. The first seven demands read:

- Universal, equal, and direct suffrage with secret ballot in all elections, for all citizens of the Reich over the age of twenty, without distinction of sex. Proportional representation, and, until this is introduced, legal redistribution of electoral districts after every census. Two-year legislative periods. Holding of elections on a legal holiday. Compensation for elected representatives. Suspension of every restriction on political rights, except in the case of legal incapacity.

- Direct legislation by the people through the rights of proposal and rejection. Self-determination and self-government of the people in Reich, state, province, and municipality. Election by the people of magistrates, who are answerable and liable to them. Annual voting of taxes.

- Education of all to bear arms. Militia in the place of the standing army. Determination by the popular assembly on questions of war and peace. Settlement of all international disputes by arbitration.

- Abolition of all laws that place women at a disadvantage compared with men in matters of public or private law.Abolition of all laws that limit or suppress the free expression of opinion and restrict or suppress the right of association and assembly. Declaration that religion is a private matter. Abolition of all expenditures from public funds for ecclesiastical and religious purposes. Ecclesiastical and religious communities are to be regarded as private associations that regulate their affairs entirely autonomously.

- Secularization of schools. Compulsory attendance at the public Volksschule [extended elementary school]. Free education, free educational materials, and free meals in the public Volksschulen, as well as at higher educational institutions for those boys and girls considered qualified for further education by virtue of their abilities.

- Free administration of justice and free legal assistance. Administration of the law by judges elected by the people. Appeal in criminal cases. Compensation for individuals unjustly accused, imprisoned, or sentenced. Abolition of capital punishment.

It is important to note that although these were serious, immediate demands, some were not “realistic” nor “winnable”. Women’s suffrage was not granted in Germany until nearly 30 years after the Erfurt Program was drafted. Replacing the standing army with a militia was perhaps the most radical of all their demands: the Prussian state was highly centralized, and to eradicate the standing army would have amounted to a revolutionary rupture within the state. When drafting a political program, even when demanding reforms, it’s important for socialists not to limit our horizons to what bourgeois politicians and their apologists tell us is possible; otherwise, we are liable to again tail their inevitable sprints to the right. Ideally, a socialist program would include measures that, once undertaken, will not only improve the condition of the working class, but begin to dismantle the dictatorship of capital.

The next group of demands were in the economic sphere, and included free healthcare, burial, a progressive tax, a series of labor demands surrounding unions, the work-day, the creation of a department of labor, etc.:

- Free medical care, including midwifery and medicines. Free burial.

- Graduated income and property tax for defraying all public expenditures, to the extent that they are to be paid for by taxation. Inheritance tax, graduated according to the size of the inheritance and the degree of kinship. Abolition of all indirect taxes, customs, and other economic measures that sacrifice the interests of the community to those of a privileged few.

- Fixing of a normal working day not to exceed eight hours.

- Prohibition of gainful employment for children under the age of fourteen.

- Prohibition of night work, except in those industries that require night work for inherent technical reasons or for reasons of public welfare.

- An uninterrupted rest period of at least thirty-six hours every week for every worker.

- Prohibition of the truck system.

- Supervision of all industrial establishments, investigation and regulation of working conditions in the cities and the countryside by a Reich labor department, district labor bureaus, and chambers of labor. Rigorous industrial hygiene.

- Legal equality of agricultural laborers and domestic servants with industrial workers; abolition of the laws governing domestics.

- Safeguarding of the freedom of association.

- Takeover by the Reich government of the entire system of workers’ insurance, with decisive participation by the workers in its administration.

The reason these demands were worth fighting for was twofold. Most obviously, things like political enfranchisement and universal healthcare alleviate some of the alienation caused by capitalist society. Perhaps more crucially though, these demands were posited by a working-class institution with a working-class awareness.

What is a working-class institution? Historically, they may mirror republican civic institutions, but within the class party. A good example of an institution within the SPD was its party school. Every class party needs political education, recruiting the working masses is a foolish endeavor without internal political clarification and cadre training- not to unquestioningly accept party dogmatism, but to properly apply the historical materialist methodology and critical analysis to the daily struggles of workers. In her piece on the SPD party school for the British Left magazine The Clarion, Rida Vaquas writes:

…the best demonstration of what the Party School could achieve of a project comes not from the words of its teachers, but from the legacies of its students. In a 1911 retrospective of the Party School after 5 years of its existence, Heinrich Schulz recorded the debts students owed their school experience: “A trade union official observes that he learned how to conceive of phenomena in economic life better through his school instruction, another gained a deeper insight into the whole political and trade union life, a third traces back his greater confidence against political and economic opponents to the school”. The school, when it succeeded, was a training in how to think, not what to think.5

Working class institution can take forms not only of political education but of what some socialists label “dual power” (though not in the way Lenin used the term). They have taken the form of free health clinics, breakfast programs for school children, housing, and worker cooperatives, or any number of things, but they need to be part of a larger project of working-class political struggle: the class party.

Despite the innovations of the Erfurt Program, the SPD, along with most of the parties from the Second International, voted for war credits in 1914 causing a traumatic rupture in the international socialist movement. There were, however, a few examples of the classical social democratic parties that retained their internationalist class solidarity. One of these was a party that contemporary American socialists can and should study, and it’s one of our own ancestors: the Socialist Party of America. The 1912 SPA platform, adopted in May at a congress in Indianapolis, follows a similar format to the Erfurt Program. The 106-year-old document is chillingly relevant. The introduction of its minimum program plainly states its ultimate goal:

As measures calculated to strengthen the working class in its fight for the realization of its ultimate aim, the co-operative commonwealth, and to increase its power against capitalist oppression, we advocate and pledge ourselves and our elected officers to the following program…

It starts with several paragraphs outlining the broad goals of the Socialist Party—its maximum program—declaring the nation to be “in the absolute control of a plutocracy which exacts an annual tribute of hundreds of millions of dollars from the producers.” It declares unilaterally that capitalism is the source of destitution in the working class, that “the legislative representatives of the Republican and Democratic parties remain the faithful servants of the oppressors”, and any legislation attempting at balancing the distance between classes “have proved to be utterly futile and ridiculous.” It says plainly that

there will be and can be no remedy and no substantial relief except through Socialism under which industry will be carried on for the common good and every worker receive the full social value of the wealth he creates.

The minimum demands of the 1912 SPA platform constitute a significant improvement compared to the Erfurt Program. Instead of two sections—one political, one economic—the SPA platform includes four sections: collective ownership, unemployment, industrial demands, and political demands. The collective ownership section only reinforces the point that the socialist platform when enacted should create a rupture in the class character of the state:

- The collective ownership and democratic management of railroads, wire and wireless telegraphs and telephones, express service, steamboat lines, and all other social means of transportation and communication and of all large scale industries.

- The immediate acquirement by the municipalities, the states or the federal government of all grain elevators, stock yards, storage warehouses, and other distributing agencies, in order to reduce the present extortionate cost of living.

- The extension of the public domain to include mines, quarries, oil wells, forests and water power.

- The further conservation and development of natural resources for the use and benefit of all the people . . .

- The collective ownership of land wherever practicable, and in cases where such ownership is impracticable, the appropriation by taxation of the annual rental value of all the land held for speculation and exploitation.

- The collective ownership and democratic management of the banking and currency system.

It is clear that the nationalization of the bourgeois state’s institutional levers of power; banks, currency, natural resources, land, distribution centers, transportation, and communications, would catalyze the disintegration of capitalist class rule. It’s important to note that these were the very first things listed on the platform.

The next section dealt with a universal jobs demand. Unlike the Erfurt Program, here the American socialists remind themselves of who their ultimate enemy is in evoking the maximum program and capitalist class “misrule”:

The immediate government relief of the unemployed by the extension of all useful public works. All persons employed on such works to be engaged directly by the government under a work day of not more than eight hours and at not less than the prevailing union wages. The government also to establish employment bureaus; to lend money to states and municipalities without interest for the purpose of carrying on public works, and to take such other measures within its power as will lessen the widespread misery of the workers caused by the misrule of the capitalist class.

This isn’t a radical demand in 2018; it’s even looking likely that Senator Bernie Sanders will make it a key point in the next presidential campaign, and he is often the first one to admit his positions are not radical. In 1912 however, before the Wagner Act of 1935 was passed, “employees… [did] not possess full freedom of association or actual liberty of contract”. The Wagner Act, also known as the National Labor Relations Act, which had legalized strikes and union organizing as well as guaranteed the right to collective bargaining, was severely gutted twelve years later under the Truman administration.

The SPA’s industrial demands contain standard labor issues that American socialists had been calling on for years, mostly dealing with workplace safety, reducing work hours, child labor laws, establishing minimum wage, etc. One calls for an establishment of a pension system. A few demands stand out, however, one prefiguring prison abolitionism calling for “the co-operative organization of the industries in the federal penitentiaries for the benefit of the convicts and their dependents.” Another calls for “forbidding the interstate transportation of the products of child labor, of convict labor and all uninspected factories and mines.” Perhaps their most creative and radical demand was “abolishing the profit system in government work and substituting either the direct hire of labor or the awarding of contracts to co-operative groups of workers.” It’s hard to imagine events like the Iraq War or the recent human disaster in Puerto Rico happening the way they did without the juicy private contracts (although there is nothing about a worker cooperative that inherently prevents it from taking part in imperial plundering).

The political demands section proposes a broad outline for transforming the state:

- The absolute freedom of press, speech and assemblage.

- The abolition of the monopoly ownership of patents and the substitution of collective ownership, with direct rewards to inventors by premiums or royalties.

- Unrestricted and equal suffrage for men and women.

- The adoption of the initiative, referendum and recall and of proportional representation, nationally as well as locally.

- The abolition of the Senate and of the veto power of the President.

- The election of the President and Vice-President by direct vote of the people.

- The abolition of the power usurped by the Supreme Court of the United States to pass upon the constitutionality of the legislation enacted by Congress. National laws to be repealed only by act of Congress or by a referendum vote of the whole people.

- Abolition of the present restrictions upon the amendment of the Constitution, so that instrument may be made amendable by a majority of the voters in a majority of the States.

- The granting of the right of suffrage in the District of Columbia with representation in Congress and a democratic form of municipal government for purely local affairs.

- The extension of democratic government to all United States territory.

- The enactment of further measures for the conservation of health. The creation of an independent bureau of health, with such restrictions as will secure full liberty to all schools of practice.

- The enactment of further measures for general education and particularly for vocational education in useful pursuits. The Bureau of Education to be made a department.

- The separation of the present Bureau of Labor from the Department of Commerce and Labor and its elevation to the rank of a department.

- Abolition of an federal districts courts and the United States circuit court of appeals. State courts to have jurisdiction in all cases arising between citizens of several states and foreign corporations. The election of all judges for short terms.

- The immediate curbing of the power of the courts to issue injunctions.

- The free administration of the law.

- The calling of a convention for the revision of the constitution of the US.

Here the Socialist Party lists some serious alterations to the existing governmental structure. They call for the abolition of the Senate with its overrepresentation for people in less populous states, the electoral college, the presidential veto, and judicial review. They demand a process for popular recall of politicians and legislation. They even call for a new constitutional convention. All of these things would be improvements and are predicated on a big enough success of the Socialist Party to implement them (otherwise, a constitutional convention could obviously be disastrous). These demands on their own however do not constitute a rupture with the bourgeois state. It is the political demands in combination with their collective ownership demands that do, by first eviscerating the major sources of economic power from their capitalists. These measures would only constitute the beginning of a revolutionary rupture from the capitalist class rule, as the last part of the platform states,

Such measures of relief as we may be able to force from capitalism are but a preparation of the workers to seize the whole powers of government, in order that they may thereby lay hold of the whole system of socialized industry and thus come to their rightful inheritance.

The socialist magazine Jacobin, which is heavily associated with the Democratic Socialists of America (and its largest chapter in New York City) has seemingly adopted as creed what Andre Gorz named “non-reformist reforms”. Gorz believed the dichotomy of the pre-war era between militant revolution or reform no longer existed. Now that armed insurrection was forever a relic of a simpler time, Gorz argued that the only route to socialism was by pushing reform that couldn’t be usurped by capital. Like many in his generation, Gorz saw the development of a postwar middle class and concluded that class struggle would forever be muted in the imperialist countries. The logical basis for this assumption can only be one thing: by entering the middle class and becoming propertied homeowners (among other things) first-world workers transitioned into a social category where revolution was no longer in their interests. As the onslaught of austerity and neoliberalism has proven, class struggle is not mutable, and to proclaim so is the gravest abandonment of the historical materialist methodology. Today, the question of reform vs. revolution is just as relevant as when Rosa Luxemburg wrote:

Legislative reform and revolution are not different methods of historic development that can be picked out at the pleasure from the counter of history, just as one chooses hot or cold sausages. Legislative reform and revolution are different factors in the development of class society. They condition and complement each other, and are at the same time reciprocally exclusive, as are the north and south poles, the bourgeoisie and proletariat.6

Truly “non-reformist reforms”, like those in the SPA platform of 1912, do not discount the possibility of a class social revolution, they depend on it. The current use of the term repeats all the same mistakes of Bernstein’s evolutionary socialism that Rosa Luxemburg famously polemicized.

The major “non-reformist reforms” today seems to be shaped around a few key maxims, not dissimilar to some of the demands from the earlier German and American socialists: “tuition-free public universities”, “Medicare-for all”, and more recently, “abolish ICE”. But how did these demands develop? They were not produced organically by working-class institutions. They were touted by individuals claiming to be democratic socialists, running on the Democratic Party ballot line. First by Bernie Sanders, next through Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Immediately they were taken up by Jacobin and the DSA.

Could socialists temporarily use the Democratic ballot line, where third party campaigns are untenable until the mass base for an independent socialist party is built? Perhaps, though this is a debate for another time. But should this really be how socialist demands are developed? Instead of echoing demands scribed by politicians, they should be echoing our demands. And our demands should be in service to the ascension of the proletariat as a politically independent class actor, and towards a rupture with the capitalist nature of the state.

The most prominent socialist group in the US, Democratic Socialists of America, lacks any real political program. Its chapters are too federated, and the biennial national conventions are not frequent nor far-reaching enough for it to be a force for class struggle on a wide scale. How can there be “non-reformist reforms” without a class organization with unified goals pushing them? Instead of allowing independent politicians with support from socialists to steer the conversation with demands like “abolish ICE”, we should be giving our demands to them. The Immigrant Justice Working Group of the Central New Jersey DSA provides for us a good example of what 21st century socialist demands look like:

- An immediate end to all detentions and deportations, and dismissal of all related charges.

- Abolition of ICE and all other military or quasi-military border forces.

- Unconditional right to asylum to be granted upon request to anyone coming from a country that has been negatively impacted by US military or economic policies, or the policies of US corporations.

- Citizenship and full rights (such as access to entitlement programs) upon request to anyone who has lived or worked in the US for at least six months.

The modern United States is not the Prussian state of 130 years ago, nor are its socialists facing the same conditions they faced in 1912. Demands that socialists make must reflect the realities of contemporary capitalism and its world system: nobody wants to merely recreate the old SPD or SPA. Still, there is no need to reinvent the wheel. Socialists should be making demands that go beyond reverting to Bush-era normalcy: they should be pushing demands that the bourgeois parties tell us are impossible, and a political program is the only way to do so. These demands should aim to build class power both in the economic and political spheres. If DSA chapters started internally adopting programs with a little vision, they could eventually map one onto the national organization. DSA needs to become part of an organization with real class power independent of the Democrats, and it will never do that without first adopting formal demands at the national level that differentiates itself as a party divested from the interests of the capitalist class. Without a political program, we have no way of seriously posing an alternative to the established parties of capital, and articulating a vision of society for the democratic class rule of workers.

- Protokoll des Parteitages der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands: Abgehalten zu Erfurt vom 14. bis 20. Oktober 1891[Minutes of the Party Congress of the Social Democratic Party of Germany: Held in Erfurt from October 14–October 20, 1891]. Berlin, 1891, pp. 3–6

- “A Critique of the Draft Social-Democratic Program of 1891”, June 1891.

- “The Program of the Parti Ouvrier”, May 1880.

- 1920.

- “What’s a Good Political Education? A Debate from the SPD”, June 2018.

- “Reform or Revolution”, 1900