Every question ‘runs in a vicious circle’ because political life as a whole is an endless chain consisting of an infinite number of links. The whole art of politics lies in finding and taking as firm a grip as we can of the link that is least likely to be struck from our hands, the one that is most important at the given moment, the one that most of all guarantees its possessor the possession of the whole chain. - Lenin, What Is to Be Done?[1]

Jonah Martell begins “A Twelve-Step Program for Democrat Addiction” by asking who “we” are. Participants in the George Floyd protests? Members of Bernie World? All left-leaning people who desire a humane welfare state? The American socialist movement? Although all of these groupings overlap with one another and share many goals and values in common, Martell believes it is the socialists who have grouped themselves together in the DSA who are the “we” that hold the greatest strategic potential. To realize that potential, however, Martell thinks the DSA has to change. Instead of a loose association of activists who label themselves socialist but follow multiple divergent political paths, ranging from realignment of the Democratic Party to socialist insurrection, Martell thinks the DSA should transform itself into a cohesive socialist party independent of the Democrats. For Martell, the idea of socialism, which was near-comatose until Bernie Sanders jolted it back to life in 2015, is the “knife that cuts us apart from the crowd.” Our job now is to reclaim the meaning of socialism from Bernie’s watered-down version and restore it to its full original strength. That is Martell’s first cut. Later, however, he makes a second cut. In Step 12 of his program, he writes that the demand for a new democratic constitution would also “truly set us apart” from the current anti-democratic system of power jointly maintained by both parties. Democracy and socialism. Two edges of the Marxist knife. Links in a chain. How are these different ideas related? Which one is more important at the moment?

It’s Martell’s Program, Not the DSA’s

Although Martell starts with the very sensible observation that “Nearly every political argument invokes a ‘we,’ a common group that should mobilize around something,” he doesn’t specify how to characterize who is putting forward the argument. If a majority of the group to which the argument is addressed agrees with the proposal, then, of course, there is no problem and the majority can proceed as an undifferentiated “we.” But if a majority of the target group rejects the proposed argument, then who “we” are becomes problematic. Is it the “I” or smaller “we” who made the proposal in the first place, or is it the larger group to which the argument was addressed?

I raise this issue of how to specify group identity because it doesn’t seem likely that Martell’s proposal for an independent socialist party will be adopted by the DSA at its next convention. What then? Martell and Cosmonaut will find themselves in much the same place as they are today: one small group with its own program along with many other groups within a much larger movement. Should this be a cause for concern? I don’t think so. It’s just a recognition of reality. It should, however, prompt a reformulation of Martell’s observation on groups. Instead of saying that political arguments usually invoke a prospective “we” that should do something, it is more accurate to say that political arguments are always put forward by an individual or group with the intention of inviting others to join them. That puts the emphasis where it belongs, on the political agency of the one making the argument. If Martell’s arguments are good, people will be drawn to them whether they become the majority position at the next DSA convention or not. Are they good? Some are better than others.

If Martell’s proposal does happen to win a majority, it wouldn’t affect what I have just said about how to identify groups. In addition to Martell’s new majority “we,” a new minority “we” would also simultaneously be created within the larger “we” of the socialist movement as a whole, and new political proposals would continue to be advanced by both the majority and various minority groups as new political problems arise. This is a never-ending process, and today’s majority can always become tomorrow’s minority. Because it seems to me that Martell’s proposal is and will remain a minority position within the DSA for some time, I am going to proceed on that assumption for now. If I am wrong, it would affect some of what I am going to say about the shape of existing organizations and political tendencies, but not the main subject about the relationship between democracy and socialism in mass agitation.

Every Proposal Is a Tactical Path

Of Martell’s twelve proposals, the first nine, particularly five through nine, are primarily projections of what the DSA should do after constituting itself as an independent socialist party. Steps 10-12 plus aspects of 9, however, do not depend on the prior establishment of an independent socialist party for their implementation. They are issues, demands, and/or critiques already being put forward and carried out today in various ad hoc ways. Which path is likely to be more fruitful? My bet is on steps 10-12 plus 9’s emphasis on the political importance of the House of Representatives. Prioritizing this second path doesn’t mean that the goal of forming an independent party is being abandoned, it just means it will come about in a different way, have a different emphasis in its program, and have a different organizational shape than the path projected in Martell’s first nine steps. In other words, at the present time, the demand for democracy is the cutting edge of the Marxist knife, the key link in the political chain. Let me illustrate what I mean by reviewing some important episodes in the history of the Russian and German Social-Democratic parties and the U. S. New Left in the 1960s.

Lenin and the Party, the Program, Factions, and Tactics

When Lenin arrived in St. Petersburg in August 1893, the Russian Marxists had no party, no factions, and no tactics apart from introducing socialist ideas to a few select workers plucked out of adult literacy classes; but they did have a program. Drawn up by Plekhanov and the Emancipation of Labor group in the mid-1880s, this program proclaimed that commodity production already did or would soon predominate in Russia and that the cause of democracy and socialism, therefore, had to be based on the growing class of urban industrial workers rather than the peasantry. Under the Tsar, however, all public political discussion was forbidden. The unique challenge facing the Russian Marxists was how to conduct political activity and eventually form a party under these conditions.

At first, Lenin merely joined the already ongoing activities of the St. Petersburg Marxist community: in intellectual circles, he carried on his critique of the populists; in worker circles, he led intense studies of Marxist fundamentals and queried workers about conditions in the factories; and in his day job as a practicing lawyer, he defended workers in court against the imposition of illegal fines and wrote a comprehensive guide to the law on fines that circulated semi-legally throughout Russia over the next ten years. Regarding the workers, the prevailing assumption was that the main task of Marxist intellectuals:

was to train a force of worker intellectuals who, armed with theory, would return to the working class to act as the catalysts in an ever-broadening schema of working-class enlightenment. They would train new worker activists and theorists who would, in turn, spread the word further; and so on, ad infinitum in geometric progression, until the whole class became conscious of its place and destiny in history. It was what we might term a chain-letter tactic for the generation of socialist consciousness.[2]

This conception of the content and propagation of socialist consciousness survived for about a year. In late 1894, however, a strike broke out at a factory where some of Lenin’s worker students were employed, yet they neither gave advance warning that grievances were building up at the plant nor showed any interest in joining the struggle of their fellow workers. Thus, the first tactical difference emerged among the Russian Marxists: whether to engage immediately in mass agitation or to continue to concentrate on socialist education for a worker elite. There were workers and intellectuals alike lined up on both sides of this question, but the majority joined Lenin in favoring the transition from propaganda for the few to agitation among the many. Using Martell’s terminology, the St. Petersburg Marxists had split into two different “we’s” on tactics, two different groups mobilized around two different forms of activity. At the same time, however, both groups remained part of a larger Marxist “we” committed at least verbally to the common goals of democracy and socialism. How did these different “we’s” interact?

During the years 1895-7, there was essentially only one “we” among the Russian Social Democrats. The strike wave that swept St. Petersburg in those years proved that the move to mass working-class agitation had been the right path to follow. Lenin expanded on the implications of these uprisings in two major essays: Draft and Explanation of a Programme for the Social-Democratic Party (1895) and The Tasks of the Russian Social-Democrats (1897). This early phase of uninterrupted growth culminated in the declaration of the formation of a nationwide Russian Social-Democratic Party at a congress attended by about a dozen delegates in early 1898. The declaration, however, turned out to be mostly symbolic because almost all of the delegates were immediately rounded up by the police. As a result of these arrests, combined with the earlier arrest of Lenin and most of the other St. Petersburg leaders, local Social-Democratic circles lost contact with one another. This period of fragmentation coincided with the rise of Bernstein’s revisionism. In Lenin’s mind, the fragmentation and isolation of local Social-Democratic organizations provided the perfect environment for Bernstein’s theory of incremental economic improvement to take root and grow. Lenin’s tactical response to this situation was two-pronged. On one hand, he upheld the original programmatic principles of the Emancipation of Labor group in a number of polemical essays. On the other, he developed his plan for Iskra to connect the isolated local Social-Democratic circles. There were several proposals floated in 1900 and 1901 for a conference to hammer out the differences dividing Social Democrats, but Lenin’s judgment was that more conferences would be useless and settle nothing. As the “Declaration of the Editorial Board of Iskra” put it:

To establish and consolidate the Party means to establish and consolidate unity among all Russian Social-Democrats, and, for the reasons indicated above, such unity cannot be decreed, it cannot be brought about by a decision, say, of a meeting of representatives; it must be worked for…Before we can unite, and in order that we may unite, we must first of all draw firm and definite lines of demarcation.[3]

I have two comments on this point. First, Lenin was being a little disingenuous in pretending that drawing lines of demarcation would lay the groundwork for eventual unity among all Social Democrats. The purpose of drawing lines of demarcation between Economism and the political primacy of overthrowing the autocracy was to isolate and neutralize the Economist trend. Lenin’s tactical plan for Iskra was to do an end-run around the Economist/tailist elements of the Party by pulling into existence a new constituency solidly united behind the original political program of the Emancipation of Labor group. This plan worked. The Iskraists were able after three years of concerted effort to convene a Party congress in which they formed the majority. My second comment is that the U. S. left now finds itself in an ideological and political situation roughly similar to that of the Russian Marxists in 1900. There now exists a sizable body of socialist opinion in the U. S., but the majority of socialists have not yet been able to draw a clear line of demarcation between themselves and the Democratic Party. Martell’s twelve points do draw clear ideological and political lines, but, like the situation in Russia in 1900, there is little chance that these positions will be adopted by a majority in the DSA any time soon. However, there is an opportunity right now for elements of the left to pursue an independent policy similar to Iskra’s based on Martell’s last four democratic steps. Like Iskra, the purpose of this independent initiative would be to create a political constituency around the demand for democracy. The state of play in Washington right now over the power of the Senate, the filibuster, voting rights, and the coming reapportionment of the House is positively screaming for a consistent democratic response from the left. More on this later. Now, back to Lenin and who “we” are.

In the Leninist mythology of old, Iskra, What Is to Be Done?, and the fight over the rules for Party membership at the Second Congress were all part of a plan to build a revolutionary party of a new type, a centralized party with a single will directed by leaders who had mastered the scientific socialist theory of Marxism. However, anyone who has ever read Chapter IV, Section E of What Is to Be Done?, “’Conspiratorial’ Organisation and ‘Democratism,’” should have recognized that this plan was designed solely to cope with the particular difficulties of operating within the Russian police state and was not intended to be a generalizable organizational model suitable for all political conditions. In Germany, where substantial if not total freedom of speech and association existed, Lenin fully accepted that elections and freedom of discussion across all levels of the party at all times were the appropriate norms. And, during the 1905 revolution in Russia, when political conditions changed and workers could for a while meet and debate openly, Lenin moved to broaden the membership of the Bolshevik organization and democratize its structure and procedures.

So, at least until 1918, Lenin never held to a fixed “concept of the party” as a faction-free centralized monolith directed by a self-perpetuating elite. His thinking on organization was that it should be shaped by the needs of the movement and take on the form necessary to carry out the most pressing tactical task of the moment. In the years 1900-3, that task was to produce and distribute a nationwide newspaper under Tsarist police censorship that would by its democratic content win over a majority of Social Democrats and create the ideological and organizational framework for a full-fledged political party. Following Martov’s refusal to abide by the decisions of the Second Congress, Lenin’s tactical and organizational focus then switched to calling for a Third Congress to reestablish the authority of the decisions of the whole Party. Then, after the 1905 uprising broke out, the focus and organization of the Bolshevik faction switched again in order to prepare for the armed overthrow of the Tsar. Throughout all of these tactical twists and turns, Lenin’s definition of who “we” are was determined, first, by the primary strategic task set out in the Party program:

Therefore, the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party takes as its most immediate political task the overthrow of the Tsarist autocracy and its replacement by a democratic republic.

But he had discovered that unity in words did not necessarily translate into unity in deeds. Programs, which can only state the general goals of a movement, have to be put into effect by the choice of particular tactics. Lenin had thought the Party formed at the Second Congress would continue to follow the tactics of Iskra, which had contributed so much to the creation of the conditions for the formation of the Party in the first place. When the Mensheviks abandoned the tactics of the old Iskra, however, Lenin and the Bolsheviks chose to continue to carry them out on their own as a separate, independent faction. The “we” of the Program and the Party had to be taken up and defended by the “we” of a tactical faction. Lenin’s actions and writings on these ideological, tactical, and organizational issues are valuable not for the teleological reason that they were precursors for the later Bolshevik revolution but because they mapped out in detail the strategic, tactical, and organizational categories and challenges that any mass movement for democracy will have to confront.

German Social Democracy: “Talking the talk, but not walking the walk”

The paths of development of Social Democracy in Germany and Russia were different, but underneath the differences, the same logic was at work. As in Russia, the most important lesson to be learned from the history of German Social Democracy is that unity around a program is not enough. Everything eventually comes down to the tactics and actions required to further the aims of the program. Let’s take a look at how Lars T. Lih, Mike Macnair, and Ben Lewis see this problem within German Social Democracy.

In “Karl Kautsky as Architect of the October Revolution”, Lih is concerned with straightening out some misconceptions about both Kautsky and Lenin that emerged in a debate involving James Muldoon, Charlie Post, and Eric Blanc. In this debate, Kautsky and Lenin were set up against one another as advocates of two different political strategies, a “democratic” strategy and an “insurrectionist” strategy, respectively. Lih rejects this dichotomy and argues that the Bolsheviks had originally drawn much of their strategic and tactical thinking from Kautsky and continued to cite many of Kautsky’s pre-1910 writings as authentically Marxist even many years after the October Revolution. Lenin’s denunciation of the “renegade” Kautsky in 1918 did not involve a wholesale rejection of Kautsky’s earlier writings. Rather, Lenin’s claim was that the later Kautsky had reneged on or failed to follow through on his original Marxist positions. Lih says that the Russian term translated as “Kautskyism” does not refer to an “ism” at all but to “a type of political behavior that can be summed up as ‘talking the talk, but not walking the walk.’” My take on Lih’s characterization of Kautsky’s lack of follow-through is that we have something to learn from identifying where, how, and why Kautsky and the SPD leadership, in general, lost their footing.

Before moving on to this question, however, it is first necessary to register an objection to one of Lih’s claims. In clarifying what he meant by saying that “Karl Kautsky even deserves to be called the architect of the Bolshevik victory in October,” Lih goes on to say:

Of course, I am not saying that Kautsky was necessarily the first to come up with these ideas or that the Bolsheviks did not arrive at them independently. But Kautsky gave authoritative endorsement to the key tactical ideas of Bolshevism, giving clarity and confidence to the Russians with an impact that is hard to overestimate.

I think it is inaccurate and misleading to call someone an architect who only endorses plans and tactics created and developed independently by others, even if that approval comes from someone in a position of authority whose words can then be enlisted in a polemical dispute with one’s opponents. Such a designation shifts the focus from the creators and initiators of tactical ideas and actions to a secondary commentator writing after the fact and distant from the front lines of battle. In the period from mid-1904 to mid-1905, for example, when Lenin was criticizing Menshevik attempts to forge agreements with the liberals, developing his theory of two tactics of Social Democracy in the democratic revolution, and organizing the Third Congress to re-establish the party’s rules and procedures, Kautsky sided with the Mensheviks and positively obstructed Lenin’s efforts, arguing publicly that the German Social Democrats should not publish the translation of the resolutions of the Third Congress in their newspapers.[4] Kautsky may have come over to Lenin’s side in 1906, but to call him the mentor or architect of Bolshevism’s fundamental tactical principles reverses cause and effect. With that little annoyance out of the way, we can move on to the search for the source of German Social Democracy’s shortcomings.

While Lih, Lewis, and Macnair agree that somewhere along the line Kautsky and the SPD leadership, in general, ceased to walk and talk like Marxists, and all agree that the vote for war credits in 1914 was the end of the line, they differ somewhat about where exactly the decisive divergence of action from principle took place and what it consisted of. As a historian, Lih tries to avoid injecting his own political opinions into this issue and limits himself primarily to recording how the Bolsheviks accounted for Kautsky’s and the SPD’s surrender in 1914. Looking back, they generally identified Kautsky’s 1909 Road to Power as his last legitimately Marxist work, and in State and Revolution Lenin identified Kautsky’s dispute in 1912 with the “Left radical” trend represented by Luxemburg, Radek, and Pannekoek as the point where Kautsky’s evasiveness on the nature of the state finally tipped over into outright opportunism[5]; but that’s as far as Lih’s observations go.

As political activists seeking to draw lessons for today from the history of Marxism, Macnair and Lewis dig deeper. In Revolutionary Strategy, Macnair identifies three areas where Kautsky and the German Social Democrats fell short of a consistent Marxist position. First, on the strategic goal of the conquest of political power and the establishment of a democratic republic:

The German party, for example, did not call openly for the replacement of the monarchy by a republic and, though the Erfurt programme contained a good set of standard democratic-republican demands (for example, universal military training, popular militia, election of officials, including judges, and so on), these played only a marginal role in the party’s agitational and propaganda work.[6]

Second, the lack of determined agitation for a democratic republic was connected to “the illusion of taking hold of and using [through the control of parliamentary institutions] the existing bureaucratic-coercive state. They [the Kautskyans] turned the idea of a democratic republic—in the hands of Marx and Engels the immediate alternative to this state—into a synonym for ‘rule of law’ constitutionalism.”[7] Third, German Social Democracy’s accommodation to the German nation-state entailed a substitution of nationalism for internationalism.[8]

In his Introduction to Karl Kautsky on Democracy and Republicanism, Lewis argues that Macnair goes too far in identifying Kautsky personally with the politics of the SPD as a whole, but Kautsky nevertheless still deserves some blame for not putting up more resistance to the party’s slide into a coalition with the German state. In Lewis’ view, “Kautsky’s main shortcoming was clearly his life-long tendency to place unity before clarity, as evinced by his contrasting resolutions on government participation to the Second International…. This trait may partly account for his later concessions to the party leadership in 1909 and so on.”[9]

So, all three of these accounts restate in slightly different ways the standard historical judgement that the German Social Democratic Party ended up not practicing what it preached. The much more interesting question is what implications for political activity today should be drawn from this German experience. It is here that I have disagreements with all three of these writers.

Last year Lih wrote an article for the Weekly Worker in Britain marking the 150th anniversary of Lenin’s birth titled “The Centrality of Hegemony.”[10] I took this article as an opportunity to express my disagreement in a letter[11] with some of the historical constructions and formulations that Lih first put forward in Lenin Rediscovered, particularly his concept of Erfurtianism and his claim that “Lenin was a passionate Erfurtian.” I wrote, in part, that:

It is astonishing, first of all, that Lih would write a more than 600-page book seeking to equate orthodox Marxism with the Erfurt programme without once mentioning Engels’ criticism of the (unchanged) draft of the political section of that programme for failing to call for the overthrow of the Prusso-German military state and the establishment of a democratic republic. Lih doesn’t engage with this simmering issue within German Social Democracy because he defines orthodoxy merely as allegiance to what Kautsky called the “merger formula”: i.e., “Social Democracy is the merger of socialism and the worker movement.” This general formula sets the standard for orthodoxy too low, because it does not take into account Marx’s and Engels’ equally important writings on the programmatic demands and political tactics needed to challenge and ultimately break through the restrictive legal barriers of an undemocratic political order. On the programmatic and agitational demand for a democratic republic, Engels was the voice of Marxist orthodoxy, not the Erfurt programme.As for whether Lenin should be called an Erfurtian, that can be settled by comparing the Erfurt programme to the program adopted by the Russian Social Democrats in 1903. The Russians—following Plekhanov’s draft programme of the mid-1880’s and not the Erfurt programme—declared that the party "takes as its most immediate political task the overthrow of the tsarist autocracy and its replacement with a democratic republic, the constitution of which would ensure: 1. Sovereignty of the people: that is, concentration of supreme state power wholly in the hands of a legislative assembly, consisting of representatives of the people [elected by universal, equal and direct suffrage] and forming a single chamber."

Lih doesn’t mention this foremost demand of the Russian programme in his book or his article and argues instead that the goal of the Russian Social Democrats in overthrowing the autocracy was merely to obtain the ‘freedom’ that the Germans had achieved under their constitutional monarchy. This definition of freedom substitutes the goal of Russian liberalism for that of the Russian Social Democrats. The Russian Social Democrats’ aim in establishing the hegemony of the proletariat in the democratic revolution was not merely to obtain the freedom to exist as an opposition party like the SPD, but for the workers and peasants to seize political power themselves. For the Russian Social Democrats, anything less than full democracy was not freedom, but just a modified form of tyranny. Lih glosses over these different meanings of freedom.

Lastly, Lih is silent on the challenges to Kautsky’s standing as the voice of revolutionary Social Democracy in the years prior to World War I, particularly the dispute that broke out between Kautsky and Luxemburg about whether to support the strikes and demonstrations in 1910 demanding suffrage reform and a democratic republic in Germany…. This dispute pushed the issue of a democratic republic to the center of Social Democratic political debate in Germany, just as Plekhanov and Lenin had pushed it to the center of debate in Russia earlier.

I am writing from the United States, where we still don’t have a democratic system of equal political representation. Lenin is still relevant for us, because he was the most dogged and consistent advocate of the democratic republic in the Second International. Lih’s ‘Centrality of Hegemony” touches glancingly on many of these crucial issues, but in the end remains too wedded to the abstract ideal of a ‘model’ SPD and the vagaries of a general ‘merger formula’ that neglects the difficulties of tactics.

Now, in substance, this criticism of the concept of Erfurtianism is not very different from Macnair’s criticism of the German party as a whole quoted earlier, yet for some reason my letter prompted Lewis and Jack Conrad to charge me with “recycling accounts from bourgeois academics and cold war historiography,” with engaging in “original sin-type argumentation,” with painting “Engels as a rejectionist” of the Erfurt programme in total, with dismissing the need for a minimum-maximum programme, and with creating “a gulf between the revolutionary ‘orthodoxy’ of Marx, Engels and Lenin, on the one hand, versus the ‘Erfurtianism’ of Kautsky and Bebel, on the other.”[12] Since I neither said nor believe any of the things that Lewis and Conrad accused me of, I’m less interested in responding directly to them than in understanding why they think defending the democratic republic as the immediate strategic task in a minimum-maximum program hinges on defending the Erfurt programme in particular. Lewis, after all, agrees that Engels’ political criticism of the programme did identify a “genuine political threat” and that “the SPD did eventually decay into a force for which the ‘democratic republic’ became something along the lines of the Weimar Republic.” What, then, is the crux of our disagreement? Lewis says that it is my unwillingness to accept that the Erfurt programme was a “revolutionary” programme and that “the SPD was a revolutionary organization.” He is right. That is the crux of the problem, but not in the way he thinks, because the question of the revolutionary character (or, as I prefer to put it, the question of the “thorough and consistent democratic” character) of the SPD or the Erfurt programme is not an either-or question. Citing Lih’s “talked the talk, but did not walk the walk” characterization, I responded:

Rather than being either unambiguously revolutionary or not, the SPD’s character was multifarious and shifting…. Engels was happy with the theoretical part of the programme dealing with the development of capitalism and critical of the political part, because it was not forceful enough. By plopping me into a made-up ‘rejectionist’ political category, Conrad and Lewis want to claim that I am creating a break between an imaginary German reformist social democracy and Russian Marxist orthodoxy. I repeat, it is not either-or. The content of the Erfurt programme, the content of Kautsky’s writings, the practice of the SPD leadership, and the sentiments of the SPD membership were by no means identical.I definitely do think that Engels’ criticism and Plekhanov’s and Lenin’s inclusion of the demand for a democratic republic in the Russian programme embody the full orthodox Marxist position; but then so do Kautsky’s writings on republicanism and the road to power, which were more consistent with an orthodox Marxist position than the Erfurt programme itself. That is why I do not see the RSDLP and the SPD as ‘worlds apart’…. I see a sliver of a crack between them (and within both of them) that gradually widened into a chasm. Because these differences were subtle and complicated and stretched over two decades, I find Lih’s concepts of Erfurtianism and the merger formula too blunt as instruments of analysis of this complex history.

Thus ended the exchange between Lewis and myself without any resolution to the question why the Erfurt programme looms so large in his thinking, so I went back and reread the Introduction to his Kautsky book for a better understanding. In reviewing the main political and academic schools of thought regarding Kautsky over the last century, Lewis identifies neo-Hegelian, Stalinist, and Cold War academic viewpoints that in various ways paint Kautsky and Lenin as “worlds apart” over their entire careers. (No argument from me on that, although he leaves out similar Trotskyist characterizations.) He then credits Lih’s Lenin Rediscovered in particular with breaking down the theoretical and political wall dividing Kautsky from Lenin that these different schools had constructed. (True enough in regard to Kautsky personally, but Hal Draper and Neil Harding had already pretty much demolished the wall separating Lenin from classical Marxism years earlier. As Lih himself attests, “when I first read Harding’s books back in the 1980s, he shook me, as he did many others, out of my dogmatic slumbers.”[13]) We agree that the theoretical part of the Erfurt programme and Kautsky’s widely read explanation of it did give a genuinely Marxist account of the development of capitalism and the general features of the class struggle, that Kautsky’s writings up until 1910, despite some wobbles along the way, also upheld genuine Marxist positions, and that Lenin often acknowledged Kautsky’s accomplishments and borrowed freely from him. (However, Kautsky also learned and borrowed from and disputed with Lenin and Plekhanov on a number of important issues. It was a two-way street.) We part company, however, when he insists, along with Lih and Macnair, that “Bolshevism itself [was] a product of this school of thought around Kautsky.”[14] No, both German and Russian Social Democracy had their roots in the work of Marx and Engels and the application of Marxism to the particular conditions of their separate countries. Their paths were parallel and interacting. Before 1906, the lineage did not run from Marx and Engels through Kautsky and the SPD over to Lenin in Russia, bypassing and superseding Plekhanov and the indigenous Russian revolutionary movement[15]; and after 1906 Lenin continued to proceed independently with or without Kautsky’s input.

This historical disagreement about the sources of Lenin’s political thinking does not necessarily have to be connected to a disagreement about the political lessons of Second International Marxism. It is possible to believe that Bolshevism was derived from the early Kautsky and also believe that the Erfurt programme and the political leadership of the SPD, including the post-1910 Kautsky, didn’t measure up to a full democratic-republican standard. In fact, Lewis’s own work on Kautsky’s early republicanism goes a long way in establishing just that. Why, then, the continued defense of the concept of Erfurtianism and an admittedly compromised Erfurt programme? It seems that Lewis thinks that a defense of Lih’s concept of Erfurtianism and the “revolutionary” character of the SPD is necessary in order to support Macnair’s proposition that Kautsky and August Bebel formed a vital and indispensable theoretical and political “center” in the Second International positioned between a class-collaborationist right represented by Bernstein and an adventurist, mass strike, direct action left represented by Luxemburg. In this formulation, Lenin is placed with the Kautskyan center and not with Luxemburg on the left, at least not until 1914.[16] This schema doesn’t hold up.

The first problem with Macnair’s framework is that it blurs two different meanings of “center” regarding Kautsky and classical Marxism. From at least the 1870s, all Marxists considered themselves part of a political center situated between various forms of liberal reformism on the right and anarchism on the “left.” In this framework, Kautsky, Luxemburg, and Lenin were all centrists. Within Marxism itself, there was no center. There was just reformism and Bernstein revisionism on the right and orthodox Marxism on the left with its minor tactical shadings. Starting in 1910, however, the term “center” began to be used to refer to divisions that had emerged within German Marxism itself, with “right” still referring to reformism, “left” refers to the likes of Luxemburg, Radek, and Pannekoek, and “center” referring to Kautsky himself. The source of this new division was the disagreement between Luxemburg and Kautsky over how to respond to the massive demonstrations and strikes that had broken out in Prussia demanding suffrage reform and then a full democratic republic. Lenin did not participate in this initial dispute, but by 1912 he began paying attention to and siding with the views of the anti-Kautskyan Marxist left. It just so happens that Lih himself has written an account of this double meaning of “center” identical to the one outlined here in an article for the Weekly Worker summarizing a review of Kautsky’s Road to Power by Zinoviev in 1909.[17] As much as there can be a consensus understanding of anything about the history of Marxism, this understanding of the double use of the word “center” beginning in 1910 qualifies.

Macnair, however, doesn’t accept this understanding of the two uses of center. He sticks with the original three-part framework of reformism, Marxism, and anarchism, all but ignores the new post-1909 usage, and shifts Luxemburg into the category of anti-party, direct action semi-anarchism. This move on Macnair’s part turns Luxemburg’s political advocacy for a democratic republic and the possibility of a political mass strike by the SPD in 1910, which neither the SPD’s official Vorwarts nor Kautsky’s Neue Zeit would print or discuss, into an all-or-nothing confrontation between a supposedly Marxist “strategy of patience” and an adventurist anarchist strategy of an immediate revolutionary general strike. At the same time, with little supporting explanation of how this categorization can work, Macnair wants to keep Lenin associated with the Kautskyan center, which had turned fully electoralist in 1910.

The biggest flaw in Macnair’s slicing and dicing of the history of German Social Democracy in this way is that it buries the problem of how to agitate and struggle for a democratic republic under dire warnings of the dangers of engaging in mass illegal protests and strikes, which is odd considering that Macnair in the passage quoted earlier criticized the SPD from its beginnings for consigning the democratic republic to a marginal role in its agitational and propaganda work. Then, as an alternative to Luxemburg’s supposed adventurism, Macnair proposes a “strategy of patience.” I don’t think this strategy is any strategy at all and involves a conceptual category mistake. The strategy of Marxism is to win the battle for democracy in order to implement socialist policies. All else is tactics. Macnair makes gestures toward this simple, classic statement of Marxism’s main strategic objective, but then adds on a number of seemingly common-sense tactical qualifications such as “patience,” the need to “win a majority” before contending for state power, plus the routine invocation that the working class must be organized. However, missing from this list is any serious consideration of Luxemburg’s, Lenin’s, and (I’ll now add) Martin Luther King’s deep involvement in mass illegal struggles for democracy, inherently risky and uncertain struggles whose outcomes could not have been known by anyone in advance. I bring up King at this point because in my exchange with Lewis I quoted from King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” to try to get across how I viewed Kautsky’s criticism of Luxemburg’s challenge to German censorship laws and her support for the demonstrations demanding a democratic republic in 1910:

[In the ‘Letter,’ King declared] ‘the time is always ripe to do right. Now is the time to make real the promise of democracy.’ In response to those who said the fight for freedom must wait for a more propitious moment, King replied: ‘This “Wait!” has almost always meant “Never!”’ I see parallels in the history of Marxism with King’s struggle against those who argued that the time wasn’t right for mass civil disobedience.

Lewis granted that King’s words were “stirring,” but then went on to say that “from the standpoint of the working class coming to power they are little more than that. As both Kautsky and Lenin underlined, making democracy real and substantial…not only requires mass discontent with the existing order, but a mass organization with a clear, strategic roadmap to guide the conscious self-liberation of the majority.”

My objection to Lewis’ formulation is that it sets up a divide between a mass movement for democracy and a supposedly separate realm of true Marxist working-class strategy and organization. Since the strategic goal of Marxism is democracy, I think our self-identity and tactical and organizational proposals are not conceptually separate from this mass movement but part of it. As Marx said of the Chartists and other democratic movements of the working class in 1848 in the Communist Manifesto: “The Communists do not form a separate party opposed to other working-class parties. They have no interests separate and apart from those of the proletariat as a whole.” Whether Marxists actually are the most advanced and far-seeing section of the working class both practically and theoretically has to be proved in the crucible of political struggle and not just proclaimed. As Lenin also underlined, sometimes Marxists lag behind the masses.

What specific practical implications flow from these different formulations of the relationship between mass movements and Marxist theories of strategy, tactics, and organization? In looking back over Macnair’s writings on strategy and the CPGB’s Draft Programme, I came across a 2006 debate between Macnair and Dave Craig from the Revolutionary Democratic Group.[18] Even though I know next to nothing about British politics or the various Marxist groups in Britain, this exchange between Macnair and Craig was still enlightening because it touched on some very general features of a debate that recurs regularly within Marxist circles. Craig argued that the efforts of Marxists in Britain should be focused first on creating a mass republican socialist party independent of the Labour Party and opposed to the constitutional structure of what he called the British “social monarchy.” Then, with some productive mass political work and enhanced credibility under their belts, Marxists would gain a better understanding of how to operate and organize themselves independently within this mass democratic movement. He called this strategy “Chartism’s second coming.” Macnair, although sharing Craig’s democratic-republican aims, argued that the primary task of Marxists should first be to unite in a new communist party around a revolutionary minimum-maximum program in order to then to fight more effectively for independent communist politics within the Labour Party. Now, very roughly and putting aside most of the details, I think the two sides of this debate correspond to the two parts of Martell’s twelve-point program. The first nine points correspond to Macnair’s party and program recommendations for Marxist unity first and the last three points correspond to Craig’s advocacy of immediate democratic-republican mass agitation in advance of and in preparation for the eventual formation of a Marxist party. Unlike Craig, however, I do not believe a mass democratic party demanding a new Constitution should be called reformist or non-Marxist, although there would undoubtedly be reformist and non-Marxist constituencies within it. Democracy is Marxist and Marxists are democrats.

Digging deeper into Macnair’s, Lewis’s, and the CPGB’s thinking about party, program, strategy, and tactics, it became clearer to me where our differences lie. Below are two selections that capture precisely where we differ, the first from Lewis’ Introduction to his Kautsky book on republicanism and the second from Macnair’s Introduction to another book of Lewis’ translation of Kautsky on colonialism:

For Kautsky, the SPD’s intransigent opposition to the state flows from its programme and overall perspectives, not from this or that particular tactic. Indeed, as long as the party’s programme were upheld, all sorts of tactical compromises and deals with other forces and social classes could be envisaged—even with those that defended the existing order: ‘Compromises are dangerous with regards to our programme, not to our actions.’ One way in which the Erfurt programme expressed its opposition was, according to Kautsky, by constantly stressing its ultimate aims:What holds political parties together—particularly when they have a great historical role to fulfil, such as the social democratic party—are its final goals, not its immediate demands; not how the party should behave regarding all the individual issues that confront it.

In other words, a mutual relationship exists between the maximum and the minimum programme: without the former, the SPD would be just another party of reform almost indistinguishable from liberal parties that shared some of the SPD’s aims; without the latter, the party would be a utopian organization with no understanding of how to create the very conditions in which its aims might be achieved. Further, the party’s ultimate aims imbued it with cohesion and purpose, avoiding unnecessary splits and fall-outs over tactical questions:

As I have argued, differences of opinion will always exist within the party, and on occasion they can reach a threatening pitch. But, the more lively the awareness of the great goals common to party members, the more powerful the enthusiasm for them, the more difficult it will be for such differences to blow the party apart, with the demands and interests of the moment taking a back seat relative to the party’s goals.[19]

and Macnair:

…the critique of Kautsky as an undialectical thinker is closely associated with a politics of fetishism of the revolutionary moment at the expense of the gradual phase of preparation for revolution; hence with fetishism of the mass strike and of ‘direct action’; and with a voluntarist conception in which the revolutionary will to action substitutes for the maturity of the objective political conditions for revolution.Before 1914, this conception (with or without Hegelian trimmings) was already associated with the construction of small bureaucratic centralist sects, like Luxemburg and her co-thinkers’ Social Democracy of Poland and Lithuania and the US and British De Leonist Socialist Labour Parties. The connection is that direct action primarily means strikes. Hence a fetishism of direct action, if it does not lead to simple spontaneism, logically implies party control of the trade unions—the policy which forced both the SKDPiL and the US SLP into marginality. Even without this policy, the emphasis on direct action means that unity on tactics is the primary focus of ‘revolutionary strategy,’ forcing tactical disagreements to lead to splits. This relationship between revolutionary voluntarism, the fetishism of direct action and the construction of small sects of the pure is completely endemic in the modern left.[20]

Almost everything in the above commentaries about parties, programs, strategy, tactics, and factions is wrong. Verbal agreement on the long-term goals of a Marxist party’s maximum program has not in the past and will not in the future prevent organizational splits over tactics. In other words, the maximum socialist section of a Marxist party program is little help in determining the specific tactics required to achieve the primary democratic goal of the minimum program. Witness Lenin versus Rabochee delo and the Mensheviks or the degeneration and disagreements that eventually split the SPD, whether 1910, 1914, 1918, or some other year is taken as the point of no return. Within other mass movements as well, there will always be disagreements over tactics that generate organizational divisions: critics of King’s tactics claimed they shared the same long-term goals. There is no way to avoid tactical disagreements and there is no way to know in advance who is right. There is, however, a way to conceptualize and regulate these inevitable tactical disagreements that avoids unfounded presumptions and unnecessary accusations. The idea that a party can be held together by a belief in the socialist historical mission of the proletariat is one such presumption and seems to be derived from the concept of one class-one party. This presumption is ideologically and organizationally top-heavy and is biased from the start toward conformity with the views of an actual or prospective leadership seeking to recruit members on the basis of this presumption. It assumes from the beginning that tactical disagreements that lead to organizational splits have to be characterized as sectarian, divisive, destructive, etc. There is no other alternative available in this conceptual framework. Macnair is vehement in defense of this viewpoint.

However, there is another way to look at this problem. Fifty years ago, Hal Draper developed an analysis and critique of the political assumptions of mini-“Bolshevik” micro-sects.[21] Chastened by the failure of Marxist groups over many years to generate any significant following or success in mass work, Draper gave up on trying to form a Marxist party or organization on a “HIGH” level of a “FULL PROGRAM” and emphasized instead the necessity “of being able to get the broadest possible masses of workers moving…in a way that would bring them into conflict with the capitalist class and its state.” In other words, organizational unity should not be based on agreement on a maximum program but on the tactics of advancing the mass movement. As an alternative to trying to form another mini-Bolshevik party, he proposed instead the formation of “political centers” organized around an editorial board of a propaganda-educational publishing enterprise. These political centers would not be the central committees of membership organizations (at least not in the short run) but the focus of a loose ideological association of sympathetic local study-political groups. These local groups would be free to tap into and draw from other political centers as well. Draper argued that this political and organizational model was drawn from the example of Lenin’s Iskra, a unique insight at the time into Iskra’s and Lenin’s true role and significance. With the political focus on advancing the mass movement rather than on the myth-riddled delusion of first forming a new revolutionary party based on a maximum program, Draper hoped to channel the energy wasted in the “party-building” debates in a more productive direction. Much better to compete in finding effective ways to generate mass activity than to compete over winning recruits to a new mini-party based on a highly elaborated doctrine.

It seems we’ve spent the last fifty years trying to catch up to Draper’s sense of where the movement was and where it needed to go, and what Marx, Engels, and Lenin were really up to. The old myth of the Leninist party has now pretty much been killed off; but, in one of history’s little ironies, it turns out that in helping to kill off the myth of Leninism Lars T. Lih’s Lenin Rediscovered has contributed at the same time to the creation of another myth called Erfurtianism. I’ve given my reasons why I think Erfurtianism is a misnomer and a historical and political curveball, and also why Draper’s concept of a political center and a focus on the immediate problem of how to advance the mass movement is the way to go. In the next section, my plan is to refer to the history of the U. S. New Left, particularly SDS, as an example of Draper’s concept of a political center, even though Draper himself never, as far as I know, referred to SDS in this way. There are several reasons why he would not have done so. First, he personally had very little interaction with SDS. The political character of the San Francisco Bay Area and Berkeley in particular differed from and was in many ways in advance of the rest of the country. SDS was a relative latecomer to this scene and was only a small part of the Bay Area New Left. Second, SDS wasn’t socialist. Draper considered it a middle-class movement distinct from working-class socialism. And third, Draper’s conception of the relationship between trade unions, the class struggle, and socialism was too economistic. He neither connected SDS’s democratic values to the problem of an undemocratic Constitution nor considered Lenin’s advocacy for a democratic republic applicable to the U. S. In his first micro-sect article, for example, Draper converted the political specificity of Lenin’s agitation for a democratic republic in Iskra into the politically indeterminate formula of a “body of doctrine…expressing a unified kind of revolutionary socialism.”

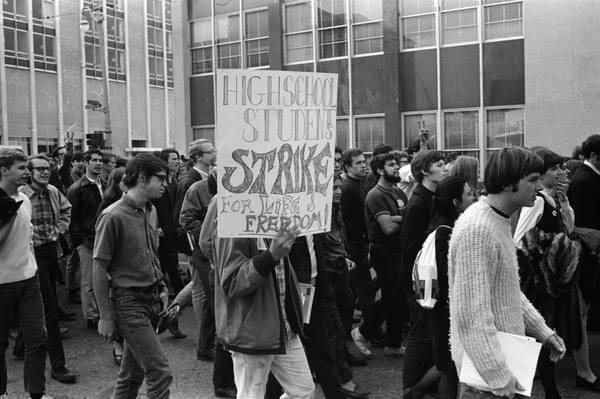

The U. S. New Left: Actions and Factions, but No Program or Party

Hardly anyone has anything good to say about the New Left except that it started out with high ideals before spiraling down into revolutionary delirium. I have a different view. SDS’s emphasis on democratic values and the failure of the U. S. to live up to its ideals came closer to identifying an undemocratic Constitution as the central political problem of the left than any of the Marxist or socialist groups at the time. In addition, in rejecting the prevailing ideological and organizational models of traditional left groups, SDS developed a non-exclusionary network of political discussion and independent political action that involved everyone from Eugene McCarthy supporters to the Marxist-Leninist Progressive Labor Party. Adjusted for population, SDS at its peak was roughly twice the size the DSA is now. The fundamental political and organizational principle governing SDS, until Weatherman violated it in 1969, was “let the factions contend” and let the members decide for themselves which action to follow.[22] There were always voices pleading that this organizational philosophy was too haphazard and that SDS had to “get organized” in order to be effective, but a majority of the membership was never convinced that any of the specific policies advanced in those pleas warranted the ideological focus or organizational tightening being proposed. The DSA has a similar open, multi-tendency structure today, which is also similar to Draper’s conception of multiple political centers experimenting with different analyses and tactics. Martell’s Twelve Steps, and the more recent proposals of the Marxist Unity Slate, seek to change this structure and form a socialist party on the basis of a minimum-maximum program similar to those of the German and Russian Social-Democratic parties.

I understand that these are well-intentioned proposals and the product of much study and discussion, but I think they overestimate what can be gained by trying to unite the DSA around a full Marxist program at the present time and lead away from possible avenues of mass activity with greater potential. For example, Martell’s recent “Fight the Constitution! Demand a New Republic!” is a stand-alone democratic argument that makes only glancing references to socialism. Where the Twelve Steps and the Marxist Unity Slate propose that socialists should break with the Democrats, form a party, and endorse only socialists, Martell’s call to Fight the Constitution speaks to a broader political constituency, but one that is also ideologically distinct from the Democrats. Like Craig’s New Chartism versus Macnair’s new communist party, Martell’s “Fight the Constitution” points in a different political direction. I think it is possible to make “I Want a Democratic Constitution” as popular as “We Are the 99%,” “Black Lives Matter,” “Fight for Fifteen,” “Medicare for All,” or SDS’s original “democratic participation in the decisions that affect our lives.” Put it on bumper stickers, T-shirts, buttons. At every demonstration, carry signs saying “I Want a Democratic Constitution.” Form a Democratic Constitution Caucus in the DSA. Start Student’s for a Democratic Constitution chapters in high schools and colleges. Write a popular pamphlet explaining “The ABCs of Democracy.” Constantly challenge the credibility and legitimacy of politicians, academics, and media personalities who blather on about the genius of the Constitution and American democracy. Make it a moral and political line of demarcation, because the Constitution is the primary obstacle that stands between us and a better world.

It is essential to understand that democracy and socialism are two distinct ideologies with different goals and often very different assumptions about what motivates mass political activity. SDS was founded on this difference, and I was surprised to find as a member of the Marxist-Leninist New Left that Lenin’s political thinking was founded on this same distinction as well. Lih gives a rough indication of this unique aspect of Lenin’s Marxism when he writes that “If you were willing to fight for political freedom, you were Lenin’s ally, even if you were hostile to socialism. If you downgraded the goal of political freedom in any way, you were Lenin’s foe, even if you were a committed socialist;”[23] but Lih’s substitution of “freedom” for “democratic republic” in the program and agitation of the Russian Social Democrats dulls the democratic edge of Lenin’s Marxist knife. It also glosses over Lenin’s associated historical claim that this distinction between democratic and socialist ideas was drawn directly from Marx and Engels. In my previous article on Lenin’s “Class Point of View,” I was mainly concerned to show how Lenin drew his conception of the two tasks of social democracy from the Communist Manifesto and how it informed his theory of the content of political agitation at its highest and most complex level. But there is also an aspect of Lenin’s theory of political agitation that is aimed at raising the consciousness of a broader mass at lower levels of political development. “The Drafting of 183 Students into the Army” is an example of this more elementary form of political agitation and is based on a simple moral appeal to repulsion against injustice. Lenin identified this basic moral sense with democracy, not socialism, beginning with his first published article in 1895, an obituary for Friedrich Engels.

About ninety percent of the Engels article is devoted to explaining the theory of scientific socialism and Engels’ contribution to its development, what Lih calls “the historical mission of the proletariat.” The concluding ten percent, however, takes a turn in another direction. Lenin writes there that:

Marx and Engels, who both knew Russian and read Russian books, took a lively interest in the country, followed the Russian revolutionary movement with sympathy and maintained contact with Russian revolutionaries. They both became socialists after being democrats, and the democratic feeling of hatred for political despotism was exceedingly strong in them. This direct political feeling, combined with a profound theoretical understanding of the connection between political despotism and economic oppression…made Marx and Engels uncommonly responsive politically. That is why the heroic struggle of the handful of Russian revolutionaries against the mighty Tsarist government evoked a most sympathetic echo in the hearts of these tried revolutionaries. On the other hand, the tendency, for the sake of illusory economic advantages, to turn away from the most immediate and important task of the Russian socialists, namely, the winning of political freedom, naturally appeared suspicious to them and was even regarded by them as a direct betrayal of the great cause of the social revolution. ‘The emancipation of the workers must be the act of the working class itself’—Marx and Engels constantly taught. But in order to fight for its economic emancipation, the proletariat must win itself certain political rights. [All emphases in original][24]

Lenin may have thought for many years that what he called Marx’s and Engels’ democratic hatred for despotism was only the special problem of Russian Marxists because Social-Democratic parties in the developed capitalist west had already fully incorporated opposition to despotism into their programs and tactics, but by 1912 he had begun to sense that maybe the west was becoming more like Russia than the other way around and that Social Democracy was wavering in its opposition to the growing threat of war and a new kind of despotism. We are still living in the aftermath of that catastrophe and the battle for democracy remains to be won.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- What Is to Be Done?, CW 4th ed., vol. 5, p. 502. ↩

- Neil Harding, Lenin’s Political Thought, vol. 1, p. 75, (St. Martin’s Press: New York, 1977) Available at archive.org and as a Haymarket paperback. ↩

- CW, vol.4, p. 354. ↩

- See Lenin’s protest against Kautsky’s intervention in “Open Letter to the Editorial Board of the Leipziger Volkszeitung,” CW, vol. 8, pp. 531-33. ↩

- Lars T. Lih, “Lenin’s Verdict on Kautsky in State and Revolution,” 8/5/2019, johnriddell.com. ↩

- Mike Macnair, Revolutionary Strategy, p. 40. ↩

- Macnair, p. 159, see also pp. 62, 160. 162. ↩

- Macnair, pp. 20, 76. ↩

- Ben Lewis, Kautsky on Democracy and Republicanism, pp. 16, 30, 39, (Haymarket Books: Chicago, 2020) ↩

- Lars T. Lih, Weekly Worker, Issue 1298, (May 7, 2020) ↩

- Gil Schaeffer, “Letter, ‘Not an Erfurtian,’” Weekly Worker, Issue 1299, (May 15, 2020) ↩

- Jack Conrad, “The Importance of Being Programmed- part 3” and Ben Lewis “Letter, ‘No Historian,’” Weekly Worker, Issue 1300, (May 21,2020). The exchange of letters between Lewis and myself continued in Issues 1301, 1302, 1303, plus an intervention by Gerry Downing in 1304, and a final letter by Lewis in 1305. ↩

- Lars Lih, “Lars Lih on Neil Harding,” marxmail.org archive 2/21/2012 ↩

- Lewis, Kautsky, p. 13 ↩

- See Richard Mullin, Lenin, Iskra and the RSDLP, 1899-1903, (2015) DPhil Thesis available at academia.edu, “Introduction” to The Russian Social-Democratic Labour party, 1899-1904, (Brill: Leiden, 2015), and “The Russian Roots of Lenin’s Political Thought,” also at academia.edu, for responses to Lih’s Erfurtian thesis. ↩

- Mike Macnair, Revolutionary Strategy, pp. 36-7, 45-8. See also Macnair’s letter in Issue 1196 of Weekly Worker and Jim Creegan’s letter in defense of Luxemburg in Issue 1197. ↩

- Lars T. Lih, “A perfectly ordinary, highly instructive document,” Weekly Worker, Issue 1087, (Dec. 17, 2015) ↩

- See articles by Macnair and Craig in Issues 645, 647, 648, and 654. ↩

- Lewis, Kautsky on Democracy and Republicanism, pp. 22-3. ↩

- Mike Macnair, “Introduction,” pp. 9-10, in Karl Kautsky On Colonialism, Ben Lewis and Maciej Zurowski, translators, (November Publications: London, 2013) ↩

- Hal Draper, “Toward a New Beginning—On Another Road: The Alternative to the Micro-Sect,” (1971) and “Anatomy of the Micro-Sect,” (1973), both at marxists.org ↩

- For a longer analysis of SDS’s ideological and organizational principles, see my “You Can’t Use Weatherman to Show Which Way the Wind Blew” at democraticconstitutionparty.com. For two descriptions of SDS’s organizational philosophy in mainstream histories, see Richard Flacks, Making History, pp. 204-5 (Columbia University Press: New York, 1988) and Kirkpatrick Sale. SDS, pp. 460-6, (Vintage Books: New York, 1974). Flacks favored SDS’s openness but thinks it was destroyed by Marxist factions; Sale criticized SDS’s openness because it blocked the creation of a centralized non-Marxist leadership capable of excluding the Marxists; I’m in favor of SDS’s openness and don’t think it was or can be destroyed by factions. ↩

- Lih, Lenin Rediscovered, p. 9. ↩

- Lenin, CW, vol. 2, pp. 26-7. ↩