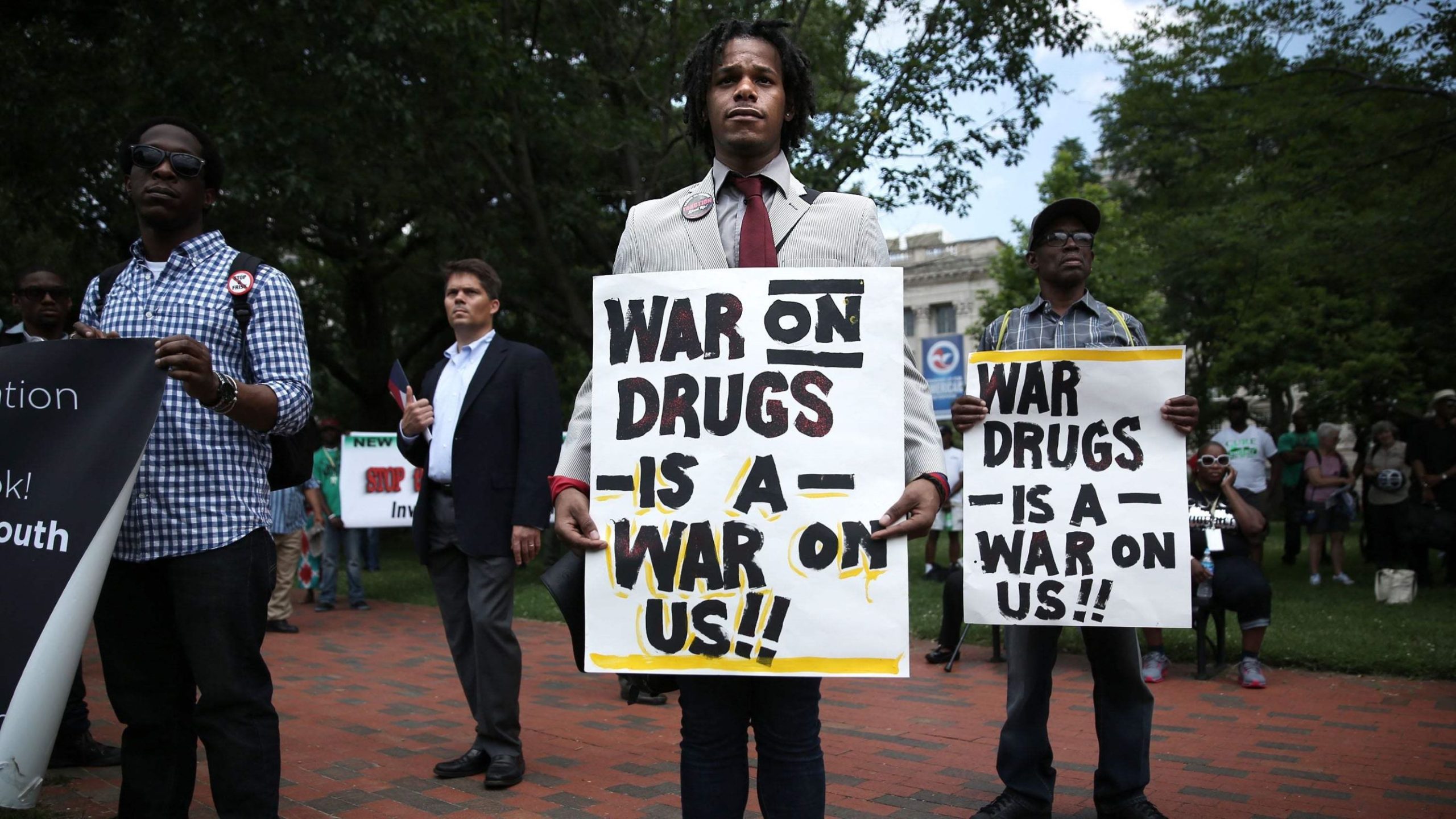

Beyond failing at preventing the ills of addiction, the War of Drugs has served as a war on those dispossessed by capitalism. Billy Anania argues that a socialist approach is needed.

This year, the War on Drugs turns 50 years old. Half a century ago, the Nixon administration introduced a hardline policy to curb the supposed problem of substance abuse, which conveniently targeted nonwhite people and his political opponents. These policies were a continuation of an unofficial war on drug users that was already underway long before Nixon’s formal declaration.

The first official drug laws in the United States targeted Chinese immigrants using opium in the 19th century. “Reefer madness” originated from fears of Mexican immigrants crossing the border. Psychedelics were first made illegal not because the government wanted to keep people from inspirational or enlightening experiences, but because Indigenous people had long treated them as sacred.

From a policy standpoint, stigmatizing drug use has failed spectacularly, ameliorating neither public health nor safety concerns. Instead, drug criminalization and law enforcement pose continuous threats to public health and safety, both in the US and abroad. Addiction is part of a larger mental health crisis linked to monopoly capitalism. This fact is often ignored in favor of research based in biological and genetic determinism, rather than the inequitable social conditions that cultivate addiction and state repression.

An opioid crisis inflated by one of the world’s wealthiest families, the Sacklers, embodies the failure of drug policy today. This private pharmaceutical industry gambles with public health outcomes for personal profit. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the number of people dying from opioid overdose increased by 120% between 2010 and 2018, and two-thirds of opioid-related overdose deaths in 2018 involved synthetic opioids like fentanyl and its analogues. Beyond prescriptions, more than 70,000 people died from general drug overdoses in 2019 alone.

In addition to failed public health efforts, drug criminalization has not brought the US any closer to a fairer, more equitable society, nor has the abstract concept of “crime” been resolved. Like other abstract forever-wars, its persistence ensures endless returns for some of the largest profiteers in history, and its criminalization is rooted in racism and anti-communism. Publications like the New York Times are manufacturing consent around crime and drug abuse in major cities, portraying last year’s uprising as a harbinger of street violence run amok. These kinds of media narratives feed into further militarizing police and expanding an already well-funded surveillance state. This circular logic is best exemplified by Andrew Yang’s latest appeal for more police in New York after cops failed to catch a shooter in Times Square, which is one of the most heavily surveilled public spaces in the world.

The socioeconomic conditions of drug use are fostered by what Karl Marx identified as “alienation” in labor, and Erich Fromm’s notion that consumerism replaces self-fulfillment through the worship of things. In his Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, Marx explains the proletariat’s position as a producer for the interests of capital: “The worker puts his life into the object; but now his life no longer belongs to him but to the object … The alienation of the worker in his product means not only that his labor becomes an object, an external existence, but that it exists outside him, independently, as something alien to him, and that it becomes a power on its own confronting him.” Work is not done for self-satisfaction, but for mere subsistence at the expense of physical and mental well-being. Alienated labor detaches humanity from its communal recognition as a species and isolates workers from each other through the creation of private property.

Fromm took this concept a step further in his 1961 work Marx’s Concept of Man, positing that estrangement applies to all language, art, and ideas. He compares the concept of idolatry, wherein humanity glorifies its own creations, to the culture of consumerism. Workers, Fromm claims, become “passive recipients, the consumers, chained and weakened by the very things which satisfy their synthetic needs. They are not related to the world productively, grasping it in its full reality and in this process becoming one with it; they worship things, the machines which produce the things — and in this alienated world they feel as strangers and quite alone.” If work and leisure are driven by consumption, then addictive habits can thus fill that void.

Despite being the wealthiest nation on Earth, the US still ranks among the lowest in mental and social well-being. A society built on individualism and competition will rarely foster solidarity, meaning many people with mental health issues are viewed as beyond repair. We need to reorient discussions of addiction in terms of communal healing, drugs as a coping mechanism for repression, and recovery as achievable through honesty and care. Stigmatizing addiction leads to double standards wielded against drug users, forcing them into a lesser social status and, worse, subjecting them to state violence.

The War on Drugs has latched onto carceral methods of social control that create and reproduce conditions for crime and deceit, enforcing laws through police, incarcerating people in for-profit prisons, and expanding the surveillance state. Meanwhile, a growing treatment-industrial complex continues to pathologize racism, sexism, and economic inequality as symptoms of mental illness. All of this is happening amid ongoing neoliberal austerity measures and economic policies, and the largest drug companies in the world refusing to share patents for COVID-19 vaccines in the Global South.

The Biden-Harris administration is pushing “mandatory rehabilitation” through a one-size-fits-all program in partnership with the carceral state. But organizers are fighting back, representing the two branches of the socialist left: mutual aid and abolition. As I hope to prove here, these are the two principles guiding those working in drug policy and developing new kinds of addiction treatment — materially benefiting people in the here-now, while envisioning a path toward liberation.

Threatening White Hegemony

Drug criminalization has largely served one purpose in the US: creating villains out of nonwhite people. The earliest drug ordinances date back to the 1870s, targeting and demonizing Chinese migrants in San Francisco who were using opium. The opium trade, first imposed on China by Britain and then the United States, became a way to control and condemn Chinese immigrants — whom whites perceived as a threat to their labor and culture.

This racist fear continued with Mexican immigrants coming over after the Mexican Revolution in 1910. The Spanish term “marihuana” was unfamiliar to white Americans at the time, but hemp and cannabis were regularly used to make clothing, paper products, and pharmaceuticals. Nonetheless, exposure to recreational use of marijuana led to President Woodrow Wilson passing the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act and virulent anti-drug campaigns in mainstream media, with misleading propaganda claiming that Mexican immigrants become violent and rape women while under the influence. Harry J. Anslinger, the first commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, even started referring to cannabis by its Spanish name to further connect the plant with foreignness.

From ex-slaves in the South to Asian sex workers and Black jazz musicians, government officials have embedded prejudices into American domestic policy. Nixon’s closest advisors have even gone on record to admit the War on Drugs was never really about substance use; he just needed a way to go after immigrants and Vietnam war protestors who were largely opposed to his presidency. The easiest way to do that was through drugs, extending a reactionary white supremacist tendency into the late 20th century. Hence, the drug war was never really about the inherent dangers of various substances; it was about criminalizing groups of people who posed a threat to white hegemony.

With policies in place, the US government continued to marginalize vulnerable communities in the Reagan and Clinton eras through the crack epidemic and the 1994 Crime Bill. While Nixon established a rhetorical war on vulnerable communities, Reagan went one step further by implementing mandatory sentencing laws, even as the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) under his administration actively funded drug cartels that flooded inner cities with cocaine and heroin. He authorized the agency to support the Contras in their war against leftist Sandinistas in Nicaragua, despite knowing their connections to drug trafficking in the US — all while First Lady Nancy Reagan promoted her famous “Just Say No” program.

Crack and powder cocaine are identical substances, but 100-to-one disparity laws disproportionately impacted crack users, who were more likely people of color living in low-income neighborhoods. Possession of crack cocaine resulted in punishment 100 times worse than that of a white person caught with powder, who would get a mere slap on the wrist, while a Black person caught with crack could face a 25-year prison sentence.

Criminalization helped expand police occupation within urban centers, and more surveillance provoked more arrests. Law enforcement continues to target Black and Brown communities, while government officials stigmatize drug use in public statements. Drug testing for employment seems nearly ubiquitous now, but it was only implemented for job interviews in 1986. Even in states where marijuana is legal, employers can still rescind a job offer or terminate someone based on it, as was the case with former Biden staffers earlier this year.

These same protocols exist for child welfare. Parents can lose custody of their children from the mere presence of drugs in their system or because a doctor reported drug abuse, even with no proof of harm to the child. Evidence of drug use can eliminate people from qualifying for public housing or financial assistance, particularly those with previous records of drug arrests.

Organizations like the Drug Policy Alliance (DPA) examine the systemic ways that criminalization takes hold of communities. DPA recently rolled out a new initiative called Uprooting the Drug War — a series of six reports that examine how the drug war has infiltrated education, employment, child welfare, public benefits, housing, and immigration. According to Matt Sutton, media director of DPA, one of the biggest findings is that the government still spends millions of dollars on drug testing in the public benefits system, yet the actual number of people who test positive is about half a percent.

“We have this idea that somewhere along the line, drugs were harming so many people that we had to outlaw them, but it’s actually always been about racism,” Sutton told me. “Much of the harm the drug war was supposedly intended to prevent is really the harm it has created, and we have to look beyond that. When a system is that racist from inception, you really do have to think about tearing the entire system down and rebuilding. I don’t think there is much from the drug war that we would want to rebuild, to be honest.”

Removing children from their home increases the likelihood of poor health outcomes, inflicting trauma on all members of a family merely because parents smoke weed, take a prescribed opiate, or even consume legal substances like alcohol and cigarettes. Likewise, money spent on drug testing far outweighs the amount saved by withholding social welfare. Of course, all of these laws are disproportionately enforced, which is why white parents can talk openly about the benefits of marijuana use. Much of the harm that drug criminalization was supposedly designed to prevent is really the harm it has sustained.

Harm Reduction

A drug offense can follow someone their whole lives, cycling them in and out of mandated treatment and incarceration. Current state-mandated treatment places the onus on the individual, further alienating people from a sense of shared struggle. In the short term, decriminalization is helping lower risks of possession arrests and immigrant deportation in Oregon, while marijuana legalization in more than 30 states has led to legislative bills like the MORE Act (Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement). Still, a system based on oppression will always find a way to adapt. Police budgets remain at an all-time high, leading critics to wonder how expungements will really pan out, and if law enforcement will merely shift to DUI charges for recreational marijuana.

The stigma linking drug abuse to petty crime remains strong, but activists are building coalitions around the harm reduction movement. While the term “harm reduction” is co-opted by liberals every election year to justify voting for a lesser evil, it originated in drug addiction treatment. Harm reduction has a long history of mutual aid and direct action predating the War on Drugs, particularly within groups like the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, and early AIDS activists. Michael Cetewayo Tabor, a former Black Panther incarcerated in New York, described illegal drug trafficking as a “plague” and wrote the following from prison in the 1960s:

“The basic reason why the plague cannot be stopped by the drug prevention and rehabilitation programs is that these programs, with their archaic, bourgeois Freudian approach and their unrealistic therapeutic communities, do not deal with the causes of the problem. These programs deliberately negate or at best deal flippantly with the socio-economic origin of drug addiction. These programs sanctimoniously deny the fact that capitalist exploitation and racial oppression are the main contributing factors to drug addiction in regard to Black people. These programs were never intended to cure Black addicts. They can’t even cure the white addicts they were designed for.”

As opposed to government-sponsored drug programs, most notably “Just Say No,” harm reduction activists have long acknowledged the continued existence of substances and aim to reduce morbidity rates through socially-oriented programs focused on autonomy, dignity, care, and radical compassion. One way that the National Harm Reduction Coalition (NHRC) accomplishes this is by limiting the lifespan of the prison-industrial complex.

Lill Prosperino, NHRC’s Southern States Regional Organizer in West Virginia, has seen first-hand how the treatment industry negatively affects ordinary people across Appalachia, a region plagued by a prescription drug crisis. Their parents both suffered from the proliferation and banning of pain pills as well as ineffective public healthcare, leading Prosperino to pursue alternative avenues. They worked in Kentucky with Qualified Health Plans (QHPs), a clinic that takes Medicare for counseling. Most of the people they met were contractually obligated by the Department of Corrections and court-ordered to attend.

“Everything at the job was in violation of ethics,” they told me. “Reporting to someone’s parole officer is not aligned with HIPAA or even with that person’s best interest and healing. Mandatory drug screening is so hypocritical in a profession that claims recovery is non-linear. They tell them it’s okay to relapse, but then have mandatory drug screening and send people back to jail after a positive screening.”

West Virginia has the highest overdose rate every year as well as an interrelated HIV crisis. Lately, Prosperino has been communicating with state legislators about the positive effects of harm reduction laws in North Carolina, including an open syringe access law, and loose regulations on syringe service programs. If a participant of a North Carolina exchange program is caught with a syringe, or tells a police officer they have syringes on them, they cannot be charged with a crime.

“I’ve seen so many people funneled in and out of jail so constantly,” Prosperino said. “Trying to do cognitive behavioral therapy, it was so much about triggers. What are your triggers? What will make you relapse? But we’re talking to people who used drugs while locked up, or are still using drugs in counseling while carrying someone else’s urine into the place. There is so much dishonesty rooted in it, not acknowledging people’s actual experience, and shoving people right back into prison. I worked in these kinds of facilities for three years, and something like 15 or 16 of my clients overdosed and passed away in treatment, because they were still clearly using. It was harmful, not therapeutic.”

Savannah O’Neill, NHRC’s Associate Director of Capacity Building based in Oakland, California, has been working to oppose a state-wide mandatory treatment bill and uplift the Reimagining Public Safety process in Oakland, which involves recommendations to the City Council on decriminalization and local strategies to deprioritize drug enforcement. Previously, she worked in facilities distributing syringes across the Bay Area. At Santa Rita Jail in Alameda County, she worked with California Forensic Medical Group to distribute naloxone to people getting out of prison and observed systemic neglect, leading her to question the ethics of their treatment methods.

“You cannot provide quality treatment for substance use disorder within a coercive system; they do not actually work together,” O’Neill told me. “I was grappling with the ethics of mitigating and indirectly contributing to the harm caused regardless of my presence. As much as I tried to help with the best intentions, I felt I was not actually reducing harm in this context.”

Most counselors in mandated treatment centers are accompanied by a guard — a built-in punitive measure that prevents people from speaking candidly about their conditions. For all the work accomplished, patients still have to go back to jail, even if counselors can create a brief moment of safety. This means workers who want to improve people’s lives actually end up feeling like they are not resolving anything. Furthermore, the medical treatment of addiction ignores the social and material conditions that produce addictive behaviors, creating the impression that all drug use is a gateway to dependency.

“For the majority of drug use, people do not experience addiction,” O’Neill said. “We treat everything now through a medical lens of addiction, so we’re also failing people who truly struggle with substance abuse disorder by treating everyone who engages with any kind of drug use as someone who needs treatment. We all know people who use drugs but do not experience fatal harm from them. This is an important distinction.”

While working in healthcare forces people to engage with systems they may not agree with, or which may not create the ideal situation, short-term remedies still do not extend the life of the prison-industrial complex. When the state fails to provide effective care for individual needs, people take care of each other and come up with their own strategies. Mutual aid requires a shift in perspective and power, and the ability to provide people with the tools to survive.

Evading the System

A fundamental class contradiction exists between Americans with healthcare, who can be prescribed medication, and those without who must seek alternatives for treatment and therapy. This discrepancy is inherently racialized, as communities of color are far more likely to be barred from private medical services and therefore less likely to access expensive pain medication, antidepressants, and therapy. Anyone left out of a public service must act accordingly, by surviving from the outside.

These racial divisions date back to Reconstruction, when immigrants and former slaves were pushed into enclosed ghettos in major northern cities like New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia — not integrated, but contained at a distance. The establishment of the Black Belt secured racial boundaries in the South, while the Great Migration led to the establishment of northern ghettos. As Saidiya Hartman explains in Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, “the enclosure of the Black Belt was to be as sharply defined in northern cities as it had been in the south; poverty, state violence, extralegal terror, and antiblack racism were essential to maintaining the new racial order” (174).

Hartman argues that living without the advantages of property ownership and generational wealth led Black and immigrant citydwellers to develop different forms of getting by. What the state dictates as “crime,” she argues, is really an attempt by oppressed people to carve out their own lives in a system that does not provide adequate space for them. Drug criminalization, therefore, punishes those seeking therapy and relief outside the for-profit pharmaceutical industry.

The War on Drugs has long been a war on people, portraying those with convictions as non-persons. For Pastor Kenneth Glasgow, co-founder of The Ordinary People Society (TOPS) and half-brother of Reverend Al Sharpton, post-release rehabilitation is full of traps to keep people bound to a low social class, and cycle them back into the prison system. Based in Dalton, Alabama, Glasgow has faced many challenges in his own road to recovery, and his activism often makes him a target for further police harassment.

Glasgow was incarcerated for robbery and drug possession at a young age and founded TOPS from prison in 1994. Since his release in 2001, he has committed to his ministry while serving Alabamans affected by the prison-industrial complex. TOPS now feeds about 300 people a day in a facility called Moma Tina’s Mission House, a soup kitchen named after Glasgow’s mother. The organization also provides clothing and shelter for rehabilitating the formerly incarcerated and unhoused. Glasgow claims his mission is full rehabilitation — everything a person needs for re-entering society.

“You can’t rehabilitate somebody who’s never been abilitated,” he told me. “That’s the first line of approach that is wrong, and there are so many people out here, so many programs, organizations, and systems that are committing malpractice. Take the reason you go see a doctor: They know how many miles of veins, capillaries, and arteries are in your body, the millions of nerve fibers in your brain and all this — I can tell you all that, because I learned it in prison. But what we cannot do is administer medicine for whatever ails that anatomy. Despite the doctor’s vast knowledge, and all they know about prescribing medicine, what is the first thing the doctor still asks? They ask what’s wrong, because they cannot make a proper diagnosis without the patient describing their symptoms. We have a whole lot of professional people making up cookie-cutter approaches and one-size-fits-all programs without talking to the individuals or those directly impacted to get a proper diagnosis.”

“I don’t call them halfway houses, because we don’t do anything halfway,” he added.

Glasgow was recently released off a capital murder charge from late 2018, in which police equated his proximity to a murder scene with actually committing the murder. The charge led Glasgow to relapse from the anxiety of returning to prison. Because Glasgow has a criminal record, government officials can keep score and maintain surveillance while he works outside the conventional methods of felon enfranchisement. The district judge in the case, Benjamin Lewis, acknowledged the outlandish charge and noted that Glasgow needed treatment for the relapse.

“What really bothered me, and what hurt the whole community, was that we were in the middle of organizing peace marches, and I had just organized one with more than 600 people against gun violence — only 36 hours before this happened,” he told me. “We know it’s retaliatory, because we helped get tens of thousands of formerly and currently incarcerated Alabamans to vote in the Doug Jones race, and effectively changed a 25-year Republican rule here; we know that’s a factor. The police even told me for the last 10 years that they would get me for something.”

Glasgow points to a fundamental contradiction in the US Constitution between the 8th and 13th amendments, wherein cruel and unusual punishment is outlawed but prisons are enforced. Private prisons often operate at 120% design capacity, perpetuating slave conditions without properly compensating inmates for their work. Additionally, many essential items are not provided for incarcerated people. Instead, they must purchase supplies like tampons, or services such as phone calls and medical visits, at extremely high prices. Every time an inmate buys something from the canteen, they pay taxes on it, and families are taxed on the money they send from outside. Beyond the ordinary products manufactured inside prisons — like license plates, furniture, and uniforms — companies like Victoria’s Secret and Microsoft have collaborated with prison administrations, all while politicians with progressive records continue to collect profits. Prisons even conduct drug trials on their inmates, treating them like guinea pigs.

During the initial COVID-19 outbreak, Alabama’s courts and jails started releasing people held for petty crimes, proving that reforms could have passed long before COVID. If they did not pose a threat during the pandemic, then what made them a threat before? It seems as if the only reason they were housing them was for monetary purposes and free labor.

Breaking the System

During the murder trial of Derek Chauvin, defense attorneys insisted that a drug overdose contributed to George Floyd’s death. Since then, Floyd’s drug use has become a major talking point among conservatives. Searching for information on Chauvin’s history of drug use, however, brings up no results. The number of police officers with histories of drug abuse is startlingly high, a statistic that contradicts the fanatical ways victims of police violence are portrayed in high-profile legal cases. This brand of racist media spin permeated the George Zimmerman trial in 2012. News networks made a spectacle of Trayvon Martin’s drug use while burying stories on Zimmerman’s own use of drugs.

The US government spends a massive amount of time and money stigmatizing disenfranchised drug users in public educational programs but avoids addressing the socioeconomic causes of addiction — to do so would be antithetical to the protection of capital and private property. It’s not just a matter of rhetoric; laws are in place to keep it this way. Pharmaceutical research is publicly funded, yet pharmaceutical companies privatize their products while healthcare companies limit who qualifies for services, effectively leaving out whoever lacks the means. This is a major reason why COVID-19 vaccine apartheid in the Global South, perpetuated by American companies like Moderna and Pfizer, will likely continue well into 2022.

Monopoly capitalism seldom leaves space for healing on our own terms, and people grappling with drug addiction are treated as medical anomalies with terminal impairments. As sociologist David Matthews notes, “the social, political, and economic organization of society must be recognized as a significant contributor to people’s mental health, with certain social structures being more advantageous to the emergence of mental well-being than others.” Matthews also points to the necessity of social work rooted in its radical tradition, popularized by Iain Ferguson. Abolition thus requires wrenching originally radical language from liberal figureheads and embodying its messages through mutual aid and direct action.

If the War on Drugs were really a means to an end, then why is the US currently at a record-high mortality rate for a drug crisis that predates Nixon? And why is this not a more popular topic of discussion in mainstream media? Decriminalization and legalized marijuana should not be methods for lining the pockets of a colonial empire. We must acknowledge how carceral medical practices stigmatize those with substance use disorder, and move toward social remedies to the ailments of individualism.

For the longer term, a public health issue like drug addiction can only truly be resolved by ending poverty, unemployment, and war — all of which are symptoms of capitalism and settler-colonialism. Free universal healthcare, drug clinics, and mental health services can accompany free education and public health initiatives, but this might cost the Pentagon some of their precious billions. Until then, the system will continue to reproduce itself ad infinitum, and the guardians of capital will remain in place to ensure its functionality, rendering concrete demands into abstraction. Our imminent goal, as socialists, should be to break that cycle.