Is the current legal definition of genocide useful for Marxists? Alyson Escalante unpacks the history behind the concept as it is currently understood and argues that a Marxist understanding of genocide must move beyond legalistic bourgeois definitions that rely on intent and look at the realities of systemic dispossession and extermination.

There are moments in history when the horrors endemic to world capitalism are brought to the forefront more clearly than ever. Crises have a way of stripping the ideological trappings of a society away and revealing the cold hard brutality which underlies liberal pleasantries. The COVID-19 pandemic represents one such crisis that has revealed the failures of capitalism on a global scale, as well as the particularly heinous failures of the American capitalist system in response to the virus. The American government and the capitalist class which it serves is all too willing to allow its own citizens to die of the disease. Over 300,000 are dead as of this writing of this article, and a change from a Republican president to a Democratic president holds little hope of bringing about significant change on this front.1 The working class has largely been forced to continue to face daily exposure to the disease, having been branded with the pseudo-honorary title of “essential worker.” The virus has also devastated colonized communities within the United States, with even the neoliberal Brookings Institute being forced to admit that Black and Latino communities are seeing mortality at shockingly elevated rates.2 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also note that Native American’s are at significantly elevated risk for contracting COVID-19 in the first place.3 As this pandemic rages on, we have also learned about forced sterilization in US ICE facilities, further demonstrating that US policies of forced sterilization of colonized communities have continued somewhat covertly to this day, even during a deadly pandemic.4 The effects of this disease have laid bare the ongoing colonial violence and brutal exploitation of the working class which is inherent to the American system of capitalism and the global system of capitalism more broadly.

In the face of this horror, we can easily find ourselves at a loss for words. When a crisis forces a society to show us what it is really made up of, the ugly horrible truths that allow it to operate, we may struggle to articulate just how horrific these realities are. In light of the intense depravity of American capitalism on display during this pandemic, we ought to have particular respect for those thinkers and organizers who seek to articulate an assessment of our current situation. One such thinker is Bree Newsome Bass, an organizer and artist who is perhaps most famous for scaling a flagpole outside the South Carolina State House in order to remove a confederate flag.5 In a particularly salient tweet, Newsome Bass summarizes and assess our current situation, writing “We’re living through an active genocide. I don’t see how else to describe this. I looked up the definition and can’t find a better term to describe what’s happened from child separation to forced sterilizations to the deliberate spread of COVID.”6 In this tweet, Newsome Bass summarizes our current moment by appealing to a very specific concept: genocide. By naming the current moment as part of a process of ongoing genocide, Newsome Bass is invoking a specific legal concept with a fraught tradition. Although she does not state the definition of genocide directly, she argues that the actions she describes constitute genocide under some definitions of the word. Furthermore, in a longer set of tweets, Newsome Bass refers to further actions as proof of ongoing genocide, pointing specifically to the ways in which vaccine shortages, scapegoating of Black people, and the lack of plans to specifically protect Black communities will lead to an ongoing trend of extremely elevated COVID mortality for Black people.7

Newsome Bass’ willingness to argue that these various actions are tantamount to genocide is worthy of defense and praise. For many Americans, genocide is understood as a foreign problem, something which occurs in Europe or Africa but certainly never here. By naming the current systemic violence as genocide, Newsome Bass follows in a long line of organizers and revolutionaries who have pointed not only to the genocidal foundations of the United States, but also to the ongoing genocides of colonized people and continuing occupation of unceded indigenous land. Bringing the category of genocide back home is important for demanding that the United States reconcile with its fundamentally colonial reality.

At the same time, we might ask: do the events that Newsome Bass points to constitute genocide under the legal definition used for the prosecution? After all, genocide is not merely a moral concept but a concrete legal category with a complex legal history. It is possible that the events Newsome Bass describes might be morally on par and worthy of condemnation with genocide, while still being excluded from the technical definition used in the prosecution of genocide. In this essay, I will argue that they do not meet this legal definition, but I must be extremely clear, I do not see this as an argument against Newsome Bass’ claim but rather as an argument that the legal definition of genocide is substantially flawed. I want not only to recognize the propagandistic importance of Newsome Bass’ claim, but to also use it as a jumping off point to consider the history of genocide as a concept, to consider the material forces at play in the development of the UN Convention on Genocide which encoded the concept in law, and finally to consider whether or not genocide as a concept is useful from a Marxist perspective.

I must reiterate, however, that my goal is not to argue that Newsome Bass is incorrect in her assessment. The concept of genocide implies a uniquely horrific act of violence worthy of intense moral condemnation and the most thorough criminal prosecution. If anything rises to that level of horror and violence, the ongoing oppression, exploitation, and extermination of colonized people within the United States certainly do.

And yet, when we explore the development of genocide as a legal concept, we discover that the legal definition of genocide functions to exclude these very forms of violence. Given this contradiction, we can use Newsome Bass’ claim as a jumping-off point for a broader critique of bourgeois law and the failure of the Genocide Convention to bring justice to colonized people. My hope is to use the question of whether or not Newsome Bass’ claim is technically and legally correct as a jumping-off point for such a critique.

A Brief Conceptual History of Genocide

In order to determine whether or not the events pointed to by Newsome Bass would fall under the legal definition of genocide, it is necessary for us to dive into the history of genocide as a concept. To understand the conceptual development of genocide, we have to understand the man who coined the term: Raphael Lemkin. A Polish-Jewish lawyer, Lemkin had a personal and direct experience of genocide at the hands of the Germans. Though he successfully fled Poland to Sweden and eventually the United States, he lost 49 relatives to the holocaust, with only himself and four others surviving through the war. Lemkin’s interest in defining and advocating against genocide was also inspired by the actions which took place during the Armenian genocide. He noted in his autobiography that he was struck by the ability for known war criminals to go free.8 These actions inspired Lemkin to develop a distinct notion of genocide, and to take action to ensure that it could be prosecuted under international law.

Lemkin eventually joined the US war department and began to conduct research into the atrocities that occured at the hands of the Nazis. During this time, he wrote Axis Rule In Occupied Europe, where he first defined genocide as:

the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group. This new word, coined by the author to denote an old practice in its modern development, is made from the ancient Greek word genos (race, tribe) and the Latin cide (killing)…. Generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves.9

This definition includes many of the important criteria that would eventually find themselves incorporated into the legal definition of genocide. It is worth noting that this definition does not reduce genocide merely to the act of killing (despite the etymological roots of the term), but rather conceptualizes genocide as a broader attempt to “destroy” a nation or ethnic group. This feature of Lemkin’s definition would become a source of controversy when it came time to develop a legal framework around genocide.

Lemkin, as a member of the US government, was involved in the process of drafting arguments to be presented at the Nuremberg Trials.10 These trials ultimately proved a decisive moment in the development of international law, as they required the further development of a theory of international jurisdiction under which war crimes could be prosecuted. Several important concepts were developed in light of these trials, including the notion of crimes against humanity. This concept was developed in order to prosecute the Nazis for war crimes which were directed not merely against enemy troops and foreign nationals, but also against their own citizenry. The charter developed to govern the prosecution of the nuremberg trial noted several crimes which rise to the level of a crime against humanity: “murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population, before or during the war, or persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds.”11 Given that the holocaust, while clearly of the utmost evil, was not illegal under any existing law, the concept of crimes against humanity was necessary to allow the tribunal to prosecute the crimes of the holocaust. The charter’s definition of crimes against humanity echos much of the definition of genocide, and this is likely not an accident. Lemkin’s notion of genocide had caught on with many American officials and doubtlessly had a major impact on the Nuremberg Trials.

The limits of the Nuremberg Trials spurred Lemkin to advocate for an expanded view of genocide which could cover actions taken outside the context of war. After all, much of the legal, technical, and social framework within Germany which was used to engage in genocide was developed in the pre-war years, yet due to the limited scope of the Nuremberg Trials, these actions were outside the realm of prosecution. Additionally, the notion of crimes against humanity emphasized a sort of universal victimhood to genocide, whereas Lemkin felt it was necessary to note the specificity of the act committed against a specific ethnic, religious, or national group. The framework of crimes against humanity did not specify that the actions of extermination, murder, enslavement, and deportation had to be committed against a particular or distinct group. Instead, the crimes against humanity framework applied to any civilian population. This framework also lacked an emphasis on intent; crimes against humanity are defined in terms of the actions taken rather than the purpose of those actions. In this sense, the framework failed to capture the specificity of the holocaust in the same way that later definitions of genocide would attempt to. Due to these limits, Lemkin felt that the Nuremberg Trials did not provide a sufficient framework for the deterrence of future genocides. He wrote that, “In brief, the Allies decided a case in Nuremberg against a past Hitler—but refused to envisage future Hitlers.”12

Given these limitations, Lemkin seized on another opportunity to create opposition to and prosecution of genocide through the newly founded United Nations. In 1946, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution in support of studying the problem of genocide in order to draft a Convention to prevent future cases. While several experts were included in the development of this Convention, Lemkin was of particular importance to the UN, having been the first person to coin the term. This eventually led to the development of the The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which was passed unanimously on December 9th, 1948. Although Lemkin was influential in the development of the Convention, the final draft which was passed excluded many of the acts of violence Lemkin had hoped to include, such as violence against specific political groups. Historical context can provide some useful insights into why such exclusions were integrated into the Convention. This post-war period saw mass violence against communists in Korea as well as the Kuomintang slaughter of communists during the latter period of the Chinese Civil War. The inclusion of political violence would have created immediate controversy and would have likely been politically infeasible in terms of garnering support for the Convention. Despite these limitations, the Convention created the necessary international framework to allow for international prosecution of genocide both during times of war and during times of peace.

In order to understand the features which came to define genocide as a legal concept with the weight of prosecution behind it, we must consider the definition laid out on the UN Convention. It is quite fascinating that Lemkin was largely successful not only in conceptualizing a crime for the first time, but also in advocating for enforcement. Though the Convention went well beyond the limitations of the Nuremberg Trials, there are still certain features of its definition of genocide that require critical investigation. The Convention defines genocide as follows:

Article II

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Article III The following acts shall be punishable:

(a) Genocide;

(b) Conspiracy to commit genocide;

(c) Direct and public incitement to commit genocide;

(d) Attempt to commit genocide;

(e) Complicity in genocide.13

There are several aspects of this definition that require very close consideration. First, the list of protected groups must be understood in a historical context. Lemkin had originally sought to include political groups within his definition of genocide, but this was removed during the drafting process at the urging of the USSR. Second, the Convention conceptualizes genocide primarilly in biological terms. While Lemkin originally emphasized a broader notion of “destruction”, the Convention lists killing, physical destruction, and bodily harm as criteria for genocide. In this sense, we might say that the Convention develops a biological theory of genocide. We will explore the limits of such a theory shortly. Finally, the definition provided by the Convention insists on these actions being conducted with the intent to destroy. This is important from a legal perspective, as most theories of criminal prosecution emphasize the necessity of intent. At the same time, this imposes a very high standard in terms of evidence, as prosecutors must demonstrate that intent was present in order for the outlined actions to rise to the level of genocide.

While the story of the genocide Convention can be read as an inspiring story of a survivor of genocide relentlessly advocating for the prevention of future atrocities, the seriousness of legal proceedings requires us to understand the Convention not merely in political terms but also in legal and sociological terms. Given this necessity, we must now turn to an in-depth focus on specific wording within the Convention as well as the effects that wording has had on the prosecution and further theorization of genocide.

Problems With the Convention’s Definition

As noted above, there are three points of concern with the Convention’s definition of genocide that we must wrestle with: the political exclusion, the cultural exclusion, and the special intent clause. These three modifications to the definition of genocide have had dramatic effects on future case law and have arguably led to the failure of the Convention to prevent future genocide. At the very least, they have created legal ambiguity around the meaning of genocide and allowed for those who engage in exterminationist actions to provide a legal defense against charges of genocide. Furthermore, I want to suggest that the reduction of genocide to a set of specific actions with special intent provides a specific temporal and spatial theory of genocide that might prove problematic if we want to prevent future genocide.

The first definitional question we must wrestle with is the exclusion of political genocide from Convention. This exclusion resulted from the lobbying of the Soviet Union during the drafting of the Convention. The Soviet Union argued that “a ‘scientific definition of genocide’ precluded the protection of political groups, who did not have immutable characteristics and were ephemeral…”14 The Soviets also opposed the inclusion of certain actions within the definition of genocide, successfully insisting that forced labor should not be included, given its own understanding of the necessity of liquidating the capitalist class as well as its choice to employ forced labor and political repression. Whether or not one sympathizes with Soviet policy at the time, it is easy to see why the USSR would oppose the inclusion of certain forms of political repression in the text of the Convention. It is worth noting that the actions adopted by the USSR under Stalin were not accepted entirely without dissent by the broader international socialist movement. Despite this dissent, the power afforded to the USSR allowed it to exert a negative influence on the convention. After all, one can hardly look to the events of the Holocaust and not consider the function of forced labor as well as the mass execution of communist dissidents. Whatever the intentions of the Soviet Union, the exclusion of political genocide has had long-lasting effects on the legacy of the Genocide Convention. Jeffrey Bachman, a lecturer at American University School of International Service explains some of the limitations of the political exclusion, writing that:

The omission of political groups from the Genocide Convention created a blind spot in its coverage into which those groups protected by the Convention can be pushed. The omission of political groups can serve this purpose by allowing the perpetrators to create and propagate a political conflict narrative, thus removing actual cases of genocide from the Convention’s coverage through defining the victimized group as a political group.15

Bachman correctly points out that the exclusion of political genocide allows for states which engage in genocide to reframe their actions as a result of political struggle. Such a reframing constitutes a rather useful defense against the charge of genocide, and at the very least, severely limits the ability to prosecute those who engage in genocide. We might also argue that the possibility of this defense undermines the deterrence effect of the Convention, as it allows those who would seek to commit genocide to mount a preemptive defense in the way they frame and justify their actions both publicly and privately.

A second definitional question raised by the Genocide Convention is the question of cultural genocide. As previously noted, the Convention primarily conceptualizes genocide in biological terms, focusing on murder, bodily harm, and physical destruction. This biological notion of genocide specifically excludes a cultural notion of genocide. Cultural genocide is succinctly defined by Tel Aviv University School of Law professor Leora Bilsky, who writes that cultural genocide can be understood as “the destruction of both tangible (such as places of worship) as well as intangible (such as language) cultural structures.”16 This notion of genocide is obviously much more expansive than the Genocide Convention’s notion if only because it includes intangible structures. Another feature of cultural genocide is an emphasis on moving beyond mere prosecution, in favor of positive “restitutive and reparative measures.” This more expansive view of genocide was actually central to Lemkin’s original theory of genocide, which held that “the essence of genocide was cultural – a systematic attack on a group of people and its cultural identity; a crime directed against difference itself.” Despite both Lemkin’s own theorization of genocide and his involvement with the development of the Genocide Convention, the Convention eventually opted to exclude cultural genocide in favor of a biological definition.

It is in the exclusion of cultural genocide that we can begin to see how politically charged the Convention’s definition of genocide really is. As soon as the UN got about to actually drafting their definition for genocide, cultural genocide was relegated to a separate article, external to the Convention draft itself. Despite Lemkin’s efforts, the drafting process continually sidelined cultural genocide, and the concept was eventually completely expunged from the Convention. While there are several factors that led to this exclusion, the overall goal of excluding cultural genocide was political in nature. Bilsky points out that, “This exclusion also shapes the common narrative of the crime of genocide… as an ideological crime that is perpetrated by totalitarian regimes and not by democratic ones.” This exclusion accomplishes this by limiting the scope of genocide to exclude less accute and more systemic forms of extermination and oppression which had occurred within various supposedly democratic states with a history of colonialism and occupation. It would not be in the interests of Britain or the United States to allow the definition of genocide to imperil their own legitimacy, and so the inclusion of cultural genocide was a proposal that was essentially dead on arrival. It ultimately was excluded for the sake of political convenience and pragmatism, to ensure that “democratic” states would endorse the Convention. According to UN documentation, the United States specifically condemned the inclusion of cultural genocide within the convention, going so far as to officially note on the record that “The prohibition of the use of language, systemic destruction of books, and destruction and dispersion of documents and objects of historical or artistic value… is a matter which certainly should not be included in this Convention.”17 While the United States position is not elaborated upon within the official UN documentation, we can easily infer that the US was likely motivated by the fact that its own treatment of indigenous peoples would clearly violate these prohibitions. In line with this inference, Bilsky notes that while the arguments against cultural genocide were framed as legal objections and practicalities, “the subtext of the discussion reveals that the real fear was expressed by states with minorities or by colonial powers that feared international interference in what they saw as internal matters.” The exclusion of cultural genocide was thus not a result merely of practicality and the limits of the juridical framework of justice, but rather served as a defense of powerful states who wanted to exempt themselves from investigation and prosecution, with the United States being a prime example. Bilsky explains that “The USA opposed the inclusion of a cultural genocide provision already at the initial stage of the Ad Hoc Committee’s proposal…” with Eleanor Roosevelt eventually arguing that “provisions relating to rights of minorities had no place in a declaration of human rights.” We can thus understand the exclusion, at least partially, as an attempt by imperialist and colonialist powers to defend themselves from claims of genocide.

While it should already be quite clear that the exclusion of both political and cultural genocide significantly limits the scope of genocide within the Genocide Convention, there is one final definitional question that must be considered. While the exclusion of political genocide regards which groups are protected under the Convention, and the exclusion of cultural genocide regards which sorts of harm qualify as genocide, the third definitional criteria deals with the context that causes actions to rise to the level of genocide. The charter notes that the actions outlined in Section II have to be undertaken with “intent to destroy” a protected group. This criteria has come to be referred to as special intent. Under the definition provided, one could engage in mass murder, great bodily and mental harm, and the prevention of the birth of new group members, but so long as one intent in doing is not an intent to destroy the group, these actions would not amount to genocide.

There are two commonly acknowledged problems that result from the specific intent requirement. First, it creates a very difficult burden of proof requirement in order for conviction to occur. In order to prove that a genocide occurred, prosecutors have to present concrete evidence that the destruction of the group was the intended goal of the defendants’ actions. Intent, in nearly all instances of criminal law, is notoriously difficult to prove. Prosecutors often look for documents or public statements wherein defendants admit to genocidal intent, but these are exceedingly rare. As a result, prosecutors are often reliant upon confessions from defendants which are even more rare.18 The special intent clause thus undermines the prosecutorial effectiveness of the Convention, but this is not its only major flaw. The clause also undermines the deterrent effect of the Convention. The goal of the Convention, and the goal of the category of genocide as theorized by Lemkin, was to both prosecute genocides that had already occurred and to deter future instances of genocide. Those seeking to engage in genocidal actions can cover their tracks by avoiding statements and documentation that demonstrate special intent. The Convention also requires that special intent be demonstrated before pre-emptive action can be taken against states undertaking a policy of genocide. Bachman points out that as a result, preventive actions thus “require proof of something only the alleged planners and perpetrators can know for sure—what the intentions are behind their actions.”19

These objections that we have examined so far are fairly well documented and established in the literature. All of these aspects of the Genocide Convention should be subjected to thorough criticism, and I suspect it is already somewhat clear how these criteria are constructed to undermine claims to genocide similar to those forwarded by Newsome Bass. It is not enough, however, to simply criticize the practical failures which result from the Convention’s definitions. I also want to problematize the underlying ontological assumptions which underpin the definition. To put this more concretely, I want to consider whether or not the Convention’s definition of genocide makes certain assumptions about the nature of genocide as a phenomena. If we want to define a social phenomena we are tasked with answering some fundamental questions about the nature of the phenomena such as: is this phenomena a one time action which is undertaken and then is completed, or is it an ongoing process which does not necessarily have a clear beginning or end? To interrogate the ontological status of genocide is to ask what sort of thing genocide is, as well as how it relates to fundamental categories such as time and place.

In as much as genocide is a thing which can be understood ontologically, the Convention understands it within a very specific spatial and temporal framework that ultimately imposes severe limits. By proposing a definition of genocide in which specific actions, specific people, and specific intent must all be present, the Convention’s definition removes genocide from its broader and structural context. The definition provided in the Convention assumes that genocide is a discreet event which has a start, an end, and is the result of specific actors taking specific and knowable actions with the intent of destroying a group. This approach ultimately temporalizes genocide by constraining our analysis of genocide to a specific historical moment. This temporalization is part of a broader event ontology which separates the actions of genocide from the broader structural forces which influenced and produced those actions.

We can make this relatively abstract ontological consideration more concrete by providing an example. Under the definition of genocide provided by the Convention, the Holocaust has a clear start date, end date, and a clear set of perpetrators. The questions that then matter in order to understand and prosecute the Holocaust are relatively simple: did the Nazis take actions that fell under Article II of the Convention? Did they take these actions with the intent to destroy a protected group? These questions are important for establishing criminal responsibility, but they also exclude certain other questions that might be necessary for understanding genocide from a systemic perspective. Under this definition of genocide, there is no concern for the broader structural crises that brought the Nazis to power and created the conditions for mass support for and public complicity in their actions. There is no consideration of the lingering effects of anti-semitism in Europe which persist after the event of the Holocaust is supposed to have concluded. Genocide is thus separated from its historical context; it is exceptionalized to a specific moment with specific actors. This account of genocide is obviously incomplete. After all, had Hitler not been the individual to rise to power, had the various generals who signed orders for the final solution not have held their posts, would the conditions that created the Holocaust not still have existed? Put another way: are the specific people, their intent, and their actions the problem, or is the problem additionally found in material conditions that produced both the context for genocide as well as the ideological justifications that these individuals employed?

One could easily object to this ontological perspective by pointing out that the domain of ontology and the domain of law are separate. While law is necessarily concerned with definition and delineation, the purpose of these definitional acts is not to establish a system by which we can understand being as such, but rather a system through which we can make practical interventions into human affairs in the goal of mediating violence and enacting justice. On some level, this objection is quite fair, but the question of genocide is perhaps an instance in which these two domains overlap in uncomfortable ways. Genocide is simultaneously a moral category that falls within the domain of philosophical inquiry and a legal category. Due to Lemkin’s own insistence on making genocide into a prosecutable crime as well as a category of socio-historical analysis, we have to wrestle with both the legal and philosophical meanings of genocide simultaneously. To the extent to which law is incapable or unwilling to grapple with the ontological dimensions of genocide, we might argue that law is not necessarily the only or the best-suited way of addressing or understanding genocide. While we cannot throw away the practical considerations that limit the legal definition of genocide, we must also wrestle with the way that such considerations have functioned to protect the interests of imperialist powers. These limitations thus simultaneously point to the subservience of the juridical sphere to class interests, as well as demonstrate the limits of bourgeois law for achieving real justice and preventing acts of genocide.

Do Bree Newsome Bass’ Arguments Meet the Legal Definition of Genocide:

At this point, I believe we have problematized the definition of genocide found in the UN Convention. Our task then is to return to the question of Bree Newsome Bass’ argument regarding genocide in the United States, to see if the actions she describes rise to the level of genocide under the problematic definition provided by the Convention. In order to do this we must first examine the actions that Newsome Bass points to and determine whether they fall under the list of actions enumerated in Article II. Then we must determine whether these actions were done to a specific protected group. Finally we must determine whether or not these actions were done with special intent. Newsome Bass lists several actions in her tweets that we can outline briefly:

- Forced sterilization (presumably the recent sterilization revelations regarding ICE).

- Child Separation (presumably the family separation policies of the Trump administration)

- The intentional spread of COVID (presumably the herd immunity strategy endorsed by Trump appointees)

- Neglect of poor Black communities during COVID prior to vaccine availability (the lack of any actual plan from Biden or Trump to address the way COVID has devastated Black communities.)

Now that we have outlined these actions, we can compare them to the language of Article II in order to determine if they fall under the list of prosecutable actions. The first two actions certainly fall under the list of actions in Article II. Forced sterilization is clearly an instance of “Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group.”20 The separation of migrant children from their families might not immediately seem to fall under the actions prohibited in the article, inasmuch as the policy does not on face transfer those children to another group. Upon closer investigation, however, we can see that the policy has de facto effect of doing so, as children who have been separated have been put up for adoption and adopted by members of another group. We can thus conclude that at least the first two actions fall under the scope of prohibited actions; although, for these to count as genocide we would also be required to prove both intent and the targeting of a protected group. We will deal with that question shortly.

In the meantime we need to consider the third and fourth actions. These are less straightforward. In terms of intentional spread of COVID-19, Newsome Bass provides little insight into the specific actions she is referencing. We can reasonably infer, however, that she was referencing a recently leaked memo from a Trump appointee that urged intentional infection with COVID-19 in order to achieve herd immunity. This memo leaked the day before her tweet, making it fairly likely that this is what she is referencing. In this memo, the Trump appointee states that “infants, kids, teens, young people, young adults, middle-aged with no conditions etc. have zero to little risk….so we use them to develop herd…we want them infected…”21 This statement can reasonably be understood, coming from a policymaker, to represent a desire for people to be infected with COVID-19. Given that such infections can produce severe results in all cases, regardless of age or pre-existing condition, we could argue that such a policy would violate Article II’s prohibition on “causing serious bodily or mental harm”. I think we can therefore likely conclude that the intentional spread of COVID infections constitutes a prohibited action.

The fourth action is, unfortunately, even more complicated. If we stop for a second to look at the wording of Article II, we can see that all of the prohibited actions are positive rather than negative. That is to say, in order for an action to count as genocide, it cannot be a failure to act in a certain way, but must rather be a decision to take a positive action which is prohibited under the article. The neglect of poor and Black communities during the pandemic certainly constitutes a choice made by the US government that reflects its own priorities, and in this sense can be understood as an action in the negative sense. Unfortunately, this is not the understanding of action employed by the Convention. Now we might argue that this neglect does constitute part of a broader prohibited action, namely “deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.” Proving this violation would require us to go beyond noting the inaction and failure of the government to take decisive action; it would require us to contextualize these actions within a broader positive policy undertaken by the state. Given these considerations, it is at least possible that the fourth claim could be disqualified from a consideration of genocide on the bases of the action-criteria established in Article II.

It seems likely that the first three actions outlined by Bree Newsome Bass could pass the prohibited action test. We therefore need to subject these three considerations to the protected group test. In relation to forced sterilizations, there is a strong case to make that these actions were taken against a group on the basis of their ethnicity and nationality. These sterilizations were performed on immigrants, who’s own legal status is derived from their nationality. Therefore, we can clearly demonstrate in the case of forced sterilization that an action prohibited under Article II was performed against a group protected by Article II. In the case of family separations, we can conclude the same thing, as the children transferred to members of another group were targeted on the bases of their nationality, and arguably on the basis of their ethnicity as well. In regards to intentional spread of COVID, things become a bit more tricky. It is not at all clear that the strategy of herd immunity is designed to target a specific group. In fact, the very notion of herd immunity requires that infections spread as far as possible. Given these considerations, it is clear that while intentional spread of COVID violates the prohibited actions criteria, it does not clearly violate the protected group criteria. Finally, although it may be possible for the fourth action to be dismissed under the prohibited action criteria, these actions are by definition committed against a protected group: Black people in the United States. This becomes somewhat irrelevant, unfortunately, as the group status of the victims is irrelevant if the action itself is not clearly prohibited.

After applying the prohibited action test and the protected group test, we finally have to turn to the special intent test in order to determine if the actions outlined in Newsome Bass’ tweet meet the legal definition of genocide. It is in the process of applying this test that we see the most obvious flaws of the Genocide Convention’s definition. In order for these actions to be prosecutable as genocide, which is to say, in order for them to meet the legal definition of genocide, we would have to be able to demonstrate that these actions were undertaken with the intent of destroying a protected group. As previously mentioned, the evidentiary standard here is remarkably high. We would need to demonstrate documentation or statements in which the perpetrators admit to their intentions. Racist and xenophobic statements alone do not meet this standard as one can make these statements without intending the destruction of a group. As such, for this burden to be met, we need an explicit admission of guilt which does not exist. ICE and the Trump administration have not admitted that the forced sterilization of families was done with the intention of destroying a group. Instead they have rationalized the actions as the actions of one specific doctor. There has also been no admission that the intention of separating families was to destroy a specific group. In the case of intentional infections, the only documentation we have justifies these actions by claiming that these infections would not be a risk to the life or well being of those infected, and by insisting that herd immunity would save lives. This obviously runs counter to the intent to destroy. Finally, in the case of neglect of Black communities during the pandemic, neither Trump nor Biden openly admit to intentionally trying to destroy Black communities, with the latter providing an abundance of shallow and surface-level statements in support of Black Americans. As such, all four actions, even the two which passed both previous tests can be dismissed when subjected to the special intent test.

I must insist, again, that my goal here is not to argue that the moral and political thrust of Bree Newsome Bass’ argument is incorrect simply because it does not meet the legal definition of genocide. On the contrary, I am arguing that we should criticize and indict the legal definition of genocide precisely because it can be used to throw out the argument made by Newsome Bass. It is utterly ridiculous that it is so easy for actors like Trump or Biden to defend themselves from the charge of genocide merely by denying intent. We must insist that the special intent clause is not an apolitical practicality of criminal law. It was developed and inserted into the Convention in order to shield imperialist and colonialist nations such as the United States from the very sorts of arguments that Newsome Bass puts forth. It is no surprise then that it can be used to dismiss her arguments; it was designed for precisely this purpose. Given this reality, it is clearly necessary that we consider whether or not the definition of genocide is useful at all in the first place. After all, when we dive into the history of the concept, we find that its very definition is inextricable from imperialist and colonial exploitation by the United States.

Before we determine how we might reconsider genocide, I want to take one final tangent. It would be easy to object to my argumentation here by pointing out that this is all purely hypothetical. Newsome Bass has not in fact presented her case to the UN and ICC for prosecution. As such, we cannot know for certain that the special intent clause would be used to throw out these claims of genocide. Fortunately, we can resolve this somewhat by looking to a historical instance in which claims that are extremely similar were in fact presented to the UN and thrown out.

The Civil Rights Congress Petition as Case Study

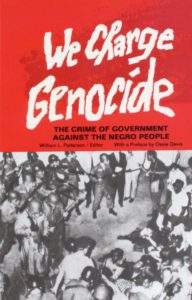

In 1951, under the heading of the Civil Rights Congress, a number of influential Black intellectuals and activists, including W.E.B Dubois and Paul Robeson, submitted a 239 page petition to the United Nations titled We Charge Genocide: The Crime of Government Against the Negro People.22 In this petition, the Civil Rights Congress alleged that the United States had violated the provisions in the Genocide Convention.

Courtesy International Publishers

There are several core arguments that the petition relied upon in order to demonstrate that the actions of the United States constituted genocide. The congress argued that the Convention does not require that a group be destroyed in whole in order for genocide to have occurred; an attempt to destroy a group in part still counts as genocide. The congress thus argued that “the oppressed Negro citizens of the United States, segregated, discriminated against and long the target of violence, suffer from genocide as the result of the consistent, conscious, unified policies of every branch of government.” The petition points specifically to the actions of the Klan, the mass lynchings of Black people across the United States, the mental harm done to Black people as a result of United States policy, the denial of the right to vote, and the various other forms of murder of Black people that have occured in the United States. 137 pages of evidence were included to substantiate these charges, and the charges were leveraged against The President, Congress, SCOTUS, the Justice Department, The KKK, the Attorney General, as well as a host of individuals.

We should note the similarity between this petition and the argument put forward by Bree Newsome Bass. The actions that Newsome Bass points to fit within the broader history of genocide that the congress lays out, and both seek to charge the United States leadership with responsibility for this history as well as the current actions of the state. Given these similarities, we might use the history of the CRC petition in order to better understand how Newsome Bass’ argument would stand up to the legal definition of genocide.

It will be no surprise to anyone to learn that the CRC petition did not ultimately succeed in leading to prosecution of the United States under the genocide Convention. According to historian Scott W. Murray, the petition was presented both to the UN Secretariat in New York and to the General Assembly.23 Despite the prominence of many of its authors and backers, the petition never gained traction. There are several factors that contributed to this, but the main factor was that it was blocked from moving forward by Eleanor Roosevelt, who was at the time the United States first delegate to the United Nations. Murray notes that Roosevelt originally expressed support for the petition, but ultimately found herself opposing and dismissing it. Roosevelt’s opposition to the treaty was expressed in the form of a definitional argument; Murray quotes her as stating that “The charge of genocide against the colored people in America is ridiculous [sic] in terms of the United Nations definition.” Unsurprisingly, we find the specificity of the UN Convention’s definition to be crucial in refusing to acknowledge the genocide of Black people in America. Summarizing Roosevelt’s objections, Murray states that there were two main arguments used to dismiss the petition. First, “although the Negro death rate is high in America, so is the birth rate” and second, “although sickness and diseases carry off more colored people than in other groups, a real effort is being made to overcome this.”

Roosevelt’s arguments in favor of dismissing the petition both rely upon appeal to the specificity of the Genocide Conventions definition. Let us briefly break down how her argument works. The first argument regarding birth rates seeks to dismiss the petition on two levels. First, it acknowledges that the killing of Black people is occurring, but argues that because birth rates are increasing at a rate which outpaces the killing, we cannot consider these killings to amount to genocide. This rather ghoulish argument seems to insist that the prohibited action is negligible if other social factors somehow mediate its effect on the overall population numbers of a group. Second, her argument implicitly contests the special intention clause. After all, if the population is allowed to remain stable or to grow, then the killings do not seem to be leading to the destruction of the population. It would therefore be difficult to conclusively prove that the killings taking place are done with specific genocidal intent.

The second argument that Roosevelt makes also operates on a definitional level. Roosevelt again begins by conceding that a problem exists: in this instance that disease and sickness lead to higher mortality rates for Black americans. At the same time she contests the intent which has led to this situation, by insisting that actions are being taken to mitigate these deaths. In this instance, Roosevelt does not really bother to contest the prohibited action component of the petition, instead focusing on intent in order to dismiss the charges. And that simply, with two arguments as concise as they are cruel, Eleanor Roosevelt was able to shield the US from genocide charges.

Having summarized the case of the CRC petition and its ultimate dismissal, we must ask what we can take away from this tragic story.

First and perhaps most concretely, we could insist on the likelihood that the charges brought forth by Bree Newsome Bass would be dismissed on the basis of the special intent clause. Roosevelt is, afterall, able to admit to disease being exceptionally devastating for Black communities while still dismissing the charges. Newsome Bass is correct that Black people have been allowed to die en masse during the pandemic, but due to the absurdity of the special intent clause, this does not amount to genocide under the Convention’s definition.

Second, we might also call into question the entire framework under which the Genocide Convention operates. The very idea of an international body which stands above the affairs of various nation states, with the ability to intervene in order to mediate conflict and prevent atrocities is undermined by how easily a single woman was able to stand in the way of justice and throw out the CRC petition. Even if the CRC petition had been embraced by Roosevelt, this would not mean that broader procedural intervention by imperialist powers could not have prevented a full hearing on the charges brought forth in the petition. Furthermore, we have to acknowledge that the very definition produced by the Convention drafting process was not an apolitical objective assessment of genocide, but a product and debate and negotiation, largely between imperialist powers. The very definition the Genocide Convention utilizes is a product of imperialist hegemony, and it undermines the very notion that apolitical international organizations can bring order to the chaos of a world stage structured by imperialism and global capitalism.

If we want genocide to be a concept and legal category that is useful for pursuing justice, and if we want it to be a category that can challenge the imperialist and colonialist powers who have perpetuated so much genocidal violence, then a reworking or perhaps even an overhaul of the concept is necessary. This is the task we turn to next.

A Marxist Perspective on Genocide

At this point, it should be painstakingly clear that the concept of genocide as defined by the United Nations is utterly insufficient to ensure justice for the oppressed. Furthermore, the definition is at least partially designed to shield imperialist powers. A tragic irony of the Convention is that the USSR ultimately aided these imperialist powers through their opposition to the inclusion of political genocide, allowing both contemporary and later slaughter of communists to fall outside the scope of genocide. I will also argue, based upon my previous arguments about the ontology of genocide, that the UN definition seeks to obscure and mystify the violence endemic to capitalist relations. In this final section, I am writing specifically as a Marxist to a Marxist audience. My goal here is to respond to the problems presented throughout this essay by providing a Marxist perspective on genocide that goes beyond and problematizes the legal definition.

A Marxist perspective on genocide must necesarilly begin by situating genocide historically in order to determine the historical processes which produce genocide. A central claim of Marxism is that capitalism is plagued by internal contradictions that lead to its inherent instability. This instability is expressed through various contradictions such as the contradiction between the socialization of labor and the anarchy of market distribution, and the various contradictions which emerge as a result of imperialist powers competing with each other. Capitalism, from a Marxist perspective, is not a stable system ruled by a class that has perfect control over society. On the contrary, the capitalist class is subject to the whims of the market and often pitted against each other both domestically and internationally. Capitalism is a system marked first and foremost by constant recurrence of crisis.

In order to understand the historical emergence of genocide, we have to understand this inherent instability. Given that the concept of genocide was developed by Lemkin primarilly in response to the Holocaust, a Marxist investigation into genocide can begin by analyzing the forces which led to the rise of fascism as well as the Holocaust. Communist theorist and revolutionary Clara Zetkin, famously defined fascism as “an expression of the decay and disintegration of the capitalist economy and as a symptom of the bourgeois state’s dissolution.”24 In the interwar period, imperialist competition between states led to the utter economic devastation of Germany. The Weimar republic faced constant economic crises, at least partially as a result of the infamous terms imposed by the treaty of Versailles. It was in the context of economic crisis, itself a lingering product of the imperialist struggles of the First World War which created the context in which fascism could emerge. Zetkin writes that, “the war shattered the capitalist economy” leading to “not only the appalling impoverishment of the proletariat, but also in the proletarianization of very broad petty-bourgeois and middle-bourgeois masses.”

Zetkin’s definition of fascism is useful in as much as it understands fascism not as an aberration or break from capitalism, but rather as a development that emerges from capitalist crisis. Given that crisis is itself endemic to capitalism, Zetkin’s account suggests that fascism is not only inseparable from capitalism, but also a potentially inherent feature. Fascism emerged as a result of instability which devastated the working class, and more importantly, caused many petty-bourgeoisie themselves to fall into the working class. Zetkin insists that this precondition for fascism is not unique to Germany, but developed in Italy as well. For Zetkin, it was the lack of security and the chaos inherent to capitalism that produced fascism and the Nazis.

Zetkin gives us the conceptual tools to understand Nazism as itself inextricable from capitalism and the context of post-war economic devastation, but we must go a bit further to understand how the Holocaust was itself a product of capitalist relation. In order to understand this, we must understand how it is that fascism emerges from crises. During moments of economic ruin, capitalism is in a particularly vulnerable place. When the system is clearly failing and not only the working class but also the petty-bourgeoisie are suffering, conditions are ripe for revolution. As a result, it is in the interests of the capitalist class to redirect class antagonism and antipathy towards a scapegoat. Historically, antisemitism has been a common means of performing this redirection. This strategy precedes the Holocaust by several decades, with the Tsarist regime and the Okhrana in particular in spreading anti-semitic conspriacy theories to slander communists and promoting anti-semitic populist movements in opposition to communism in Russia. In Germany, this anti-semitic strategy took on unique elements as a result of the specificity of capitalism. Not only were the Jewish people tied to communist conspiracy in order to displace antipathy away from the capitalist class, but a whole complex distinction between the nation/volk and internal enemies was constructed to justify genocide. This is not to say that the racial and nationalist framework developed by the Nazi regime was entirely unique to this specific moment of capitalist crisis. The Nazis simultaneously responded to and capitalized on conditions of crisis with a distinct German ideology while also drawing upon the history of settler-colonial extermination abroad. Hitler himself referenced the United States as an inspiration. As such, the Nazi’s genocidal actions drew on a history of nation-building and capitalist development internationally. We can thus insist that the anti-semitic and genocidal pogroms that occurred under the Tsar and the holocaust are both instances in which xenophobic ideology was mobilized in order to displace class war directed at the bourgeoisie in order to stabilize a potentially revolutionary situation. This demonstrates that genocide can occur both as a result of fascism but also a result of crises more broadly. Furthermore, the extent to which the Nazis drew on the exterminationist actions of the United States indicates that the technology of genocide deployed during a moment of crisis was also developed within the context of an expanding settler-colonial state intent on the accumulation of land during a period of economic growth. We can thus see genocide emerging both in moments of capitalist expansion as well as crisis.

We must acknowledge that genocide is obviously not inherently bound with fascism; genocides occur in contexts wherein fascism (at least as understood by Zetkin) has not developed as well. Given this reality, we must explain how genocide is inherently tied to capitalism and class society even when fascist development is not present. Even in these instances which occur outside the context of fascism, the forms of xenophobic and racist attitudes that facilitate genocide are often in the interest of the capitalist class. In the most basic instance, this is because a divided working class is a working class which is very unlikely to turn its sights on the ruling class. This is why Marxism has always emphasized internationalism and opposition to racial chauvinism. We might therefore conclude that the existence of capitalism itself produces the conditions in which xenophobic ideology is allowed not only to exist but to flourish.

Furthermore, in more complex instances such as the instances of anti-Black genocide in the United States, we can understand slavery and its lingering impacts a result of the unique path capitalist development took in the United States, and the ongoing need for an imprisoned class of laborers who are not compensated for their labor. The transformation of chattel slavery into the prison industrial system stands as evidence of the economic and material function that anti-Black racism has taken in the United States. The United States has relied on enslaved labor in addition to traditional proletarian labor pools since its earliest days. Anti-black racism has been at the core of securing this pool of enslaved labor; the material base upon which American capitalism is built is thus reliant upon this particular form of racism and its accompanying ideology. Additionally, theorists such Harry Haywood have demonstrated the extent to which there is an internal Black nation within the United States which can best be understood in terms of colonial and capitalist exploitation and oppression. It is clear that the United States, a thoroughly capitalist and imperialist entity, has historically enacted genocidal violence and continues to adapt its violence to new legal frameworks. To see the genocidal component of American chattel slavery we need only to look to attempts to control the reproduction of slaves, separate families for the sake of destroying the cohesion and creating economic profit for slave owners, as well as the obvious physical and mental harm that were central to the control of slave populations. All of these actions constitute genocide, even while they stop short of total extermination. Since slavery required the maintence of the most basic physical wellness of slaves, the genocidal aspects of chattel slavery were somewhat at odds with the goals of physical extermination while still being aimed at the destruction of a cultural group for the sake of profit and economic growth. Slavery thus demonstrates the need for a theory of genocide that is not merely biological but also cultural. The economic function of slavery and anti-black racism demonstrate the essential link between genocide and capitalist development within the United States. As such, absent opposition to capitalism, imperialism, and the states that serve to protect them, it is not possible to mount a meaningful opposition to genocide. Even outside the context of European fascism, wherever we find genocide we also find class conflict and capitalist interests.

Much more could be said to demonstrate the inherent link between genocide and class society (capitalism in particular), but such an investigation into other instances of genocide is beyond the scope of this essay. For now, it will have to suffice to have demonstrated the link between capitalism and genocide in a few exemplary instances.

If the Marxist perspective on genocide contextualizes genocide within class struggle and capitalist crisis, it must also question the utility of the Genocide Conference’s definition as well. As I argued earlier, the underlying event ontology of the Conference’s definition serves to dehistoricize genocide by drawing an artificial delineation between the event of genocide and the historical and material context which surrounds it. This move serves to protect capitalism from the realization that genocide does not occur in a vaccum as a result of the actions of a few evil ill-intentioned men. Absent this event ontology, we might consider the ways the capitalism produces genocide, and might therefore conclude that the responsibility for genocide lies not only with the individual perpetrators, but with a whole socioeconomic order. The definition of genocide provided by the Conference thus not only is used by imperialist powers such as the United States to dismiss accusations of genocide, it also maintains an ideological function to mystify genocide itself.

Furthermore, the notion of intent is particularly problematic from a Marxist perspective inasmuch as the capitalist conditions which produce genocide are beyond the control of any given individual and often act against the intent of members of the ruling class. The focus on intent is at its core a liberal misdirection that allows the problem of genocide to be pinned on specific individuals who are assumed to be an aberration from the norm. As such, it serves to protect the ruling class and the capitalist system more broadly from a systemic critique. Given that inherent crisis and market instability cause capitalism to work against the interests of individual capitalists, we must acknowledge that the conditions from which genocide emerges are often impossible to conceptualize in terms of intent. They seem, instead, to operate on the basis of a totalizing logic of capitalism which plays itself out beyond the control or intent of any individuals. As such, the concept of special intent is also incapable of conceptualizing a systemic or collective responsibility in which a specific socioeconomic system can be indicted. The Marxist perspective on genocide must necessarily move beyond such an individualist framing in order to make the charge of genocide not only against those individuals who engage in it but also against the capitalist system that produces the conditions in which these individuals act. Our view of genocide cannot let individuals off the hook, but it must expand the notion of responsibility beyond a question of intent to a question of the systemic function of genocde in times of crisis.

If we are to properly undertake a Marxist critique and reconfiguration of genocide, we must also question the entire legal context in which genocide prosecutions take place. The very idea of prosecution via international courts such as the ICC or ICJ relies upon a certain liberal institutionalist framework which assumes that international third party institutions can intervene into instances of international and domestic conflict in order to mitigate violence. The very history of the Genocide Convention denies the supposedly neutral standing of these institutions. We know that the development of the Convention’s definition was undertaken with the interests of specific states in mind, particularly the interests of imperialist and colonialist states. Given this insight we must push back against the idea that the UN, ICC, or ICJ are in fact neutral third parties capable of intervening in the name of an international public good. Instead, we must point to the ways that these institutions are tools used by imperialist states to protect their interests. A truly universal justice cannot be achieved through courts of bourgeois law, regardless of whether or not those courts are domestic or international.

These critiques do not mean, of course, that the concept of genocide is totally useless. Lemkin clearly has good reason to insist on the insufficiency of the previous crimes against humanity framework. It is important to be able to point to particularly heinous and genocidal crimes in order to morally condemn them and to insist on the necessity of ruthlessly combating them. The truth found in Bree Newsome Bass’ argument is precisely that there is a view of genocide that is worth defending and articulating. This is simply not the view found in the legal definition.

If we are to maintain and uphold the concept of genocide as uniquely worthy of moral condemnation and criminal prosecution, then we should certainly embrace a holistic notion of genocide which includes cultural genocide. We must, however, question at least on some level the utility of genocide as a concept. A holistic account of genocide does not, unfortunately, resolve the problems created by the special intention criteria. We can embrace a view of genocide which includes cultural genocide, but so long as a focus on intent is present, we insist on a notion of genocide which is temporalized to a specific moment, reduced to a specific set of actions taken by a discrete set of actors, planned in advance with clear motive outlined in evidence. Such a view necessarily excludes violence that results from systemic causes and is produced as a product of social totality beyond the control of any given specific members of the ruling class. The deaths created by these systemic crises and the unrelenting anarchy of capitalist market relations are very sizable and certainly worthy of equal moral and criminal condemnation as genocide. Furthermore, if we understand genocide as a product of capitalist crisis and colonialism, we can argue that the specific actions of discrete individuals which lead to temporally and geographically specific instances of genocide are themselves a product of a broader totality. Therefore, we might conclude that genocide as a concept which seeks to exceptionalize specific instances of violence serves to obscure the broader context in which that violence occurs and to direct criticism, condemnation and criminal and moral responsibility towards a set of individuals rather than the social totality which produced those individuals. In this sense, the exceptionalization of genocidal violence within the UN Convention serves an ideological and obfuscatory function in defense of world capitalism and the murderous logic in which it has proliferated into an overarching whole.

A Marxist perspective on genocide, therefore, has to understand genocide as a product of the historical and ongoing development of capitalism. We must understand the relationship between genocide and crisis while insisting that crisis is an inexorable aspect of capitalism. It is also crucial to demonstrate that even in times of relative stability, capitalist and colonialist states such as the United States maintain the conditions of genocide for the economic benefit of the capitalist system. Furthermore, a Marxist perspective must call into question the individualist framework of special intent in order to elucidate the relationship between individuals who undertake genocidal actions and the material context in which they are able to successfully commit genocide. It is my hope that the historical analysis and critical perspective presented here can act as a starting point for the development of such a perspective.

In the hopes of further developing this Marxist perspective, I hope to offer a revised definition of genocide that can account for and include the actions pointed to by Newsome-Bass. After all, if we decide that the concept of genocide is one which we should maintain and continue to utilize both as a moral critique and legal charge, then we must develop such a definition which can account for the structural nature of genocide. A first step towards such a definition would be the reintroduction of cultural genocide. In line with this, we can look to Lemkin’s own definition of cultural genocide in the earlier draft of the Convention. Lemkin argued specifically for prohibiting “systematic destruction of historical or religious monuments or their diversion to alien uses, destruction or dispersion of documents and objects of historical, artistic, or religious value, and of objects used in religious worship” as well as “forced and systematic exile of individuals representing the culture of a group.”25 The inclusion of this language within a definition of genocide would allow for us to consider racially or ethnically motivated cultural destruction as well as incarceration as genocide. As such, it would allow us to understand much of the anti-black violence that Newsome-Bass points to as genocide.

In order to make this new expanded definition really work, however, we must also remove one central aspect of the Convention’s definition. So long as the special intent clause exists, the convention’s definition of genocide is largely useless for Marxist ends. The opening line of article two of the Convention should be edited to remove any reference to intent at all, instead of focusing on the effects of the prohibited actions. This would mean that genocide is not determined by whether specific individuals sought to destroy a group by means of prohibited actions, but rather is determined by whether or not said actions (regardless of intent) led to the destruction of a protected group in part or in whole.

Finally, this revised definition of genocide would have to modify the language surrounding protected groups in order to ensure that political groups are protected as well. This modification would be necessary to ensure that genocidal actions could not be justified on the basis of political strife. Afterall, the imprisonment of Black revolutionary leaders might fall under a prohibited action under our new definition, but if our list of protected groups does not include political groups, a hostile state could claim that said imprisonment is on the basis of politics rather than nationality or ethnicity.

If we were to integrate these changes we could rewrite Article II and Article III of the Genocide convention to read as follows:

Article II

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts which result in the destruction of, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, political or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

(f) Systematically destroying historical or religious monuments or diverting them to alien uses, destroying or dispersing documents and objects of historical, artistic, or religious value, and objects used in religious worship

(g) Forcefully and systematically exiling individuals representing the culture of a group.

Article III The following acts shall be punishable:

(a) Genocide;

(b) Conspiracy to commit genocide;

(c) Direct and public incitement to commit genocide;

(d) Attempt to commit genocide;

(e) Complicity in genocide.

This reworked definition would radically alter the meaning of genocide such that it could account for broader systemic forms of violence which result not from specific individuals but from broader material conditions. It would also allow us to understand genocide through a framework that is not purely biological in nature. This in turn would allow us to account for cultural destruction as a broader aspect of genocide. Given these modifications, this definition of genocide would have obvious political utility for a progressive political project. If we return briefly to the claims made by Newsome-Bass, we can see a concrete utility to this definition. Newsome-Bass’ accusations of genocide would be vindicated under this modified definition, allowing the concept of genocide to be employed by those organizers and revolutionaries struggling to overcome the conditions which produce genocidal violence.

While this reworked definition of genocide allows us to conceptualize genocide in a more productive manner, it does not resolve all of the broader problems with the Genocide Convention. The Convention and the UN on the whole were and are still dominated by imperialist powers. Whatever definitions we may come up with lack actual weight and power as a result of this reality. As such, this alternative definition is perhaps most useful for clarifying the problems with the Genocide Convention and the liberal view of international law which assumes that genocide can best be combatted through institutions such as the UN. The insufficiency of the Convention’s definition is made more clear through this alternative definition. This allows us to point to the need for a broader struggle against capitalism and imperialism in order to combat genocide. If an alternative definition of genocide is to ever have the force of law behind it, we must first transcend the limits of bourgeois law and legal institutions through a broader struggle against capitalist rule. Hopefully, this alternative definition can help us understand the necessity of this broader struggle and the task of combatting imperialism.

This task is of political importance inasmuch as it is inextricable from the broader political task of proletarian revolution. As Marxists, we must undertake an analysis of genocide defined not on the terms of imperialist powers like the United States but on the terms of the masses who have suffered under the weight of capitalism and colonialism. We must insist on a solution to genocidal violence not found in the hands of impotent international institutions which are ultimately subservient to those same imperialist powers. Instead we must insist on a solution that begins with developing the power of the masses to fight for their own justice, absent reliance upon any international bourgeois court. We must develop a view of genocide which does not toss out the arguments put forward by Bree Newsome Bass, but instead demands reparations and restitution for the genocidal legacy of American slavery and anti-Black racism. Such a view of genocide understands responsibility to lie not simply with a small handful of criminals but with a system that consistently and repeatedly produces the conditions for genocide to occur. Our new view of genocide must be a proletarian and anti-colonial view, and it can only be theorized and put into practice through the struggle of the masses against the capitalists and imperialists.

- https://jacobinmag.com/2020/12/biden-coronavirus-covid-lockdown-science

- https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/06/16/race-gaps-in-covid-19-deaths-are-even-bigger-than-they-appear/

- https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0819-covid-19-impact-american-indian-alaska-native.html

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/09/25/ice-is-accused-sterilizing-detainees-that-echoes-uss-long-history-forced-sterilization/

- https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/bree-newsome-removes-confederate-flag-south-carolina-state-house

- https://twitter.com/breenewsome/status/1339796456438439936?lang=en

- https://twitter.com/breenewsome/status/1338862129282084869

- Lemkin, Raphael; Frieze, Donna-Lee (2013). Totally Unofficial, The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 19, 20. ISBN 9780300188066.

- http://www.preventgenocide.org/lemkin/AxisRule1944-1.htm

- https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/coining-a-word-and-championing-a-cause-the-story-of-raphael-lemkin

- https://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/judprov.asp

- https://www.facinghistory.org/holocaust-and-human-behavior/chapter-11/raphael-lemkin-and-genocide-Convention

- https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/atrocity-crimes/Doc.1_Convention%20on%20the%20Prevention%20and%20Punishment%20of%20the%20Crime%20of%20Genocide.pdf

- https://academic.oup.com/ahr/article/124/2/632/5426315

- https://repository.library.northeastern.edu/files/neu:153

- https://academic.oup.com/ejil/article/29/2/373/5057075

- https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/604195?ln=en#record-files-collapse-header

- https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2206245

- https://repository.library.northeastern.edu/files/neu:1538/fulltext.pdf

- https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/deported-parents-may-lose-kids-adoption-investigation-finds-n918261

- https://www.politico.com/news/2020/12/16/trump-appointee-demanded-herd-immunity-strategy-446408

- https://www.Blackpast.org/global-african-history/primary-documents-global-african-history/we-charge-genocide-historic-petition-united-nations-relief-crime-united-states-government-against

- https://prism.ucalgary.ca/bitstream/handle/1880/51806/9781552388860_chapter05.pdf;jsessionid=37F37296EF84F49441A32F5AC79B271D?sequence=8

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/zetkin/1923/06/struggle-against-fascism.html

- https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/611058?ln=en