Gil Schaeffer responds to Renzo Llorente’s “The Contradictions and Confusions of ‘Democratic Socialism” and argues that socialists need to base their politics on a coherent ethical theory of democratic rights.

Introduction

On 12/19/2021, Cosmonaut published an odd article by Renzo Llorente titled, “The Contradictions and Confusions of ‘Democratic Socialism”. Llorente’s article is odd, first of all, because it takes no notice of the political discussion that has been going on within the US socialist movement for the past three years regarding the undemocratic structure of the US Constitution, a discussion initiated and led by Cosmonaut itself. Llorente speaks only of “liberal democracy,” as if this term usefully represents the political world we inhabit.

Satisfied that he has correctly identified the essential character of the US political system, Llorente then wants to move on to argue that socialism is incompatible with liberal democracy; but here, again, his argument takes an odd twist, because Llorente soon grants that John Rawls has in fact established in his theory of justice that socialism is compatible with liberal democratic principles. However, this seeming contradiction doesn’t slow Llorente down. He proceeds to put Rawls’ theory aside as a possible grounding for democratic socialist principles because the dominant capitalist political forces in the US continue to claim in their propaganda that the public ownership of the means of production is incompatible with democracy. Abandoning Rawls’ theory, for this reason, is a non sequitur. The question of whether socialism is theoretically compatible with liberal democratic political rights is entirely separate from the practical problem of how to combat capitalist propaganda in the public political arena. If socialism can genuinely and usefully be derived from liberal democratic principles, and the capitalists deny this, then the answer is not to abandon liberal democratic principles but to defend them against the capitalists’ disinformation campaign.

It turns out, however, that Llorente isn’t really interested in the problem of basing socialism on a theory of liberal democratic rights at all. Instead, he wants to establish that working-class rule and socialism require a new conception of political rights that are distinct from theories of universal democratic rights. He attempts to perform this maneuver by first picking out an innocuous slogan from the DSA website that describes socialism as a system where “working people…run both the economy and society democratically.” He then claims that the use of the word “democratically” in this kindergarten formulation “cannot mean what it means for liberal-democratic theory, which rejects the view that a particular class, stratum, sector, etc. of society is uniquely entitled to run the economy and society.” This is just pedantic nitpicking. Because “the proletarian movement is the self-conscious, independent movement of the immense majority, in the interest of the immense majority,” there is no great difficulty involved in establishing that the rule of the working class is simultaneously a system of universal democratic rights.

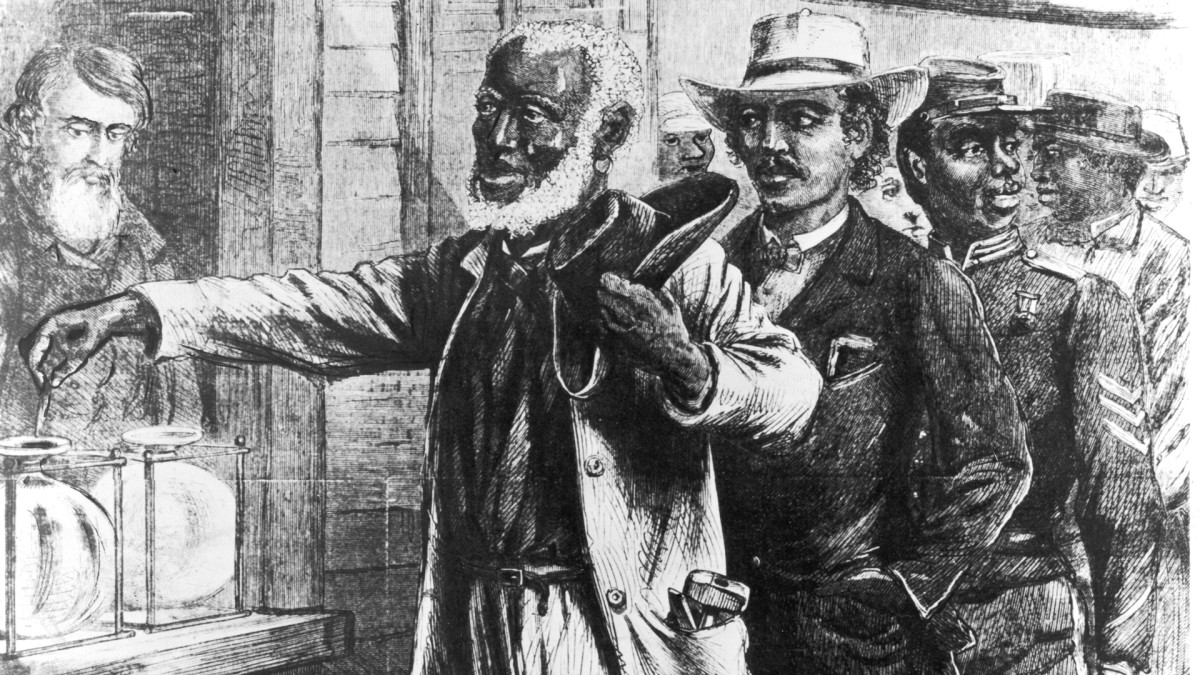

Finally, even though Llorente devotes much of his article to examining the logical relations between the concepts of liberal democracy and socialism, his overriding concern lies elsewhere. As the quotation from Rosa Luxemburg at the top of his article indicates, Llorente’s real concern is whether liberal democratic principles are capable of coping with the extreme conditions that would prevail during and immediately after a violent socialist revolution. His conclusion is that they are not, which is what ultimately lies behind his argument that a reconceptualization of a specifically socialist, working-class system of non-liberal democratic rights is necessary. To this aspect of Llorente’s article, I have a two-part response. First, Llorente consigns to a footnote and then dismisses Rosa Luxemburg’s criticism of Lenin’s and Trotsky’s justifications for the banning of parties and newspapers in Russia after the revolution. Whatever the political exigencies of the moment, Luxemburg insisted that adherence to the traditional democratic principles of freedom of speech, press, assembly, and suffrage and their widest possible practical implementation was absolutely necessary in order to prevent the revolution from sinking into a new form of bureaucratic police rule. Revolutions shatter societies. They then need to be rebuilt on new political, economic, social, and juridical foundations; a process that has invariably proven to be extraordinarily difficult. Part of that rebuilding process requires the reintegration into social and political life of many who originally opposed the revolution. Just saying that we need to deny political rights to a small number of ex-capitalists and their allies during and after the revolution does not even begin to touch on the complexities involved. Although it would take some work to draw out the analogy fully, I think the period of the American Civil War and Reconstruction is the most illuminating historical example we have of the interplay between establishing democracy and enforcing new laws of property and political rights against a defeated class of dispossessed property owners engaged in remorseless, illegal resistance. I’ll have a little more to say about this example at the end of the article. Second, even if one is convinced that the capitalists will never give up power peacefully, this conviction tells us next to nothing about the political content of the activity we should engage in outside of the rare conditions of a revolutionary crisis. Lenin was certainly convinced that violence would eventually be required to overthrow Tsarism, but so what? Did that conviction lead him to fill Iskra with calls to prepare for armed insurrection? No. He filled Iskra with articles demanding democratic rights and the establishment of a democratic republic. The same was true of Luxemburg in Germany. The only way to prepare for whatever the ruling class will throw at us in a crisis is to organize a movement around clear political goals before the crisis. Absorbed in speculations about what measures might be needed during and after a violent revolution, Llorente has nothing to say about what we should be doing and saying in the meantime. I don’t think this absence of advice on how to conduct political activity in the here and now is an accident. It seems to be a general rule among Marxists that the more they focus on the necessity of violence in a future revolution, the less they are able to provide useful advice for current practice.

Liberal Democratic Rights Are Too Important to Be Left Hanging in Limbo

As pointed out above, Llorente grants that there are political theorists, such as John Rawls, who believe that liberal democracy is compatible with socialism. He would have served his readers better if he had also mentioned that there are political theorists, such as C. B. Macpherson, who hold that socialism is not only compatible with liberal democratic rights, but also that socialism is necessary for the ultimate fulfillment of liberal democratic rights. Unfortunately, because he thinks this entire line of liberal democratic theorizing is a dead-end, Llorente drops the ball on the relationship between liberal democratic rights and socialism. Because I think there is nothing more important in the world than understanding and fighting for liberal democratic rights, I’m going to pick up Llorente’s fumble and run with it. I believe it is necessary to do so because there seems to be some misunderstanding and confusion about the relationship between democratic rights and socialism within the Cosmonaut orbit itself. Below are a few examples to indicate where I see a problem.

I thought I remembered that both Mike Macnair and Donald Parkinson said somewhere that socialism and the working-class movement couldn’t be based on a “mere ethic.” I looked through a bunch of their writings but couldn’t find those exact words. However, I did find some roughly similar statements that can serve just as well as illustrations. Here is a quotation from Macnair that captures the general tenor of his theoretical outlook:

At the same time, however, if the full effect is given to Banaji’s negative critique of the ‘traditional Marxist’ scheme, but no positive alternative scheme of general historical development is put in its place, Marx’s and Engels’ core arguments for the leading role of the proletariat in the struggle against capitalism also fall to the ground for the same reason. What is left is merely an ethical or utopian socialism. This ethical or utopian socialism may prioritise the working class, as Banaji’s actual politics does. But it lacks serious and solid grounds for supposing that working class self-activity under capitalism points toward a future without capitalism.1

I disagree that we should characterize Marx’s economic and historical investigations as a “scheme,” that we sink into utopianism if we don’t have a “scheme,” or that constructing a strategy for democracy and socialism in the US does not rest on “serious and solid grounds” if it is not based on a “general scheme of historical development.” I believe Macnair’s “scheming” leads him into a conceptual paradox regarding the problem of practical political activity and agitation. This problem came up recently when he took me to task for rejecting “the Marxist class perspective in favor of a democracy-first perspective.”2 I responded that he misunderstood the argument in my two articles published in Cosmonaut.3 Basing my position on Lenin’s theory of political consciousness and agitation in Chapter 3 of What Is to Be Done? and the article in Iskra, “Political Agitation and ‘the Class Point of View,’” my argument was that democracy is the Marxist class perspective. Democracy is also an ethic, it is not utopian, and it is seriously and solidly based on the truism that democracy is necessary in order to advance the economic, political, and social interests of the working class. However, my argument for democracy rested only on Lenin’s (and Rosa Luxemburg’s) reputational authority combined with the “duh!” factor that the US is not a democracy. It did not seek any broader philosophical grounding, it did not even begin to discuss the vexed problem of Marx’s attitude toward the concepts of rights and justice, and it stayed even farther away from what historical materialism is supposed to mean and whether it is a science or not. Now, these big questions are on the table.

Donald Parkinson had a few things to say about ethics in “Faith, Family and Folk.”4 Seeking to explain the phenomenon of traditional leftists accommodating themselves to conservative cultural values, Parkinson acknowledged that “Another factor is the lack of an (at least explicit) ethical framework in Marxism, a belief system that exists as counterposed to utopian socialists who aimed to build socialism on the foundation of ethical ideals.” Parkinson went on to say:

The desire for an ethical grounding beyond the scientific analysis of history provided by Marxism is real. It is my opinion that for us communists, ethical nihilism is not a tenable option. A basic ethical worldview is needed. Perhaps we can find this in the ethics of classical republicanism, a discourse that was implicit in the entire early socialist movement that Marx and Engels were embedded in.

These are sound intuitions, but they are somewhat at odds with Cosmonaut’s expressed mission to “Make socialism scientific again!” Just recently, for example, Cosmonaut decided to reprint Nikolai Bukharin’s Historical Materialism, a book that is as far from providing a useful ethical worldview as one can get. Coincident with Cosmonaut’s discussion of Bukharin’s book on Patreon, Jim Farmelant posted an article on Quora titled, “Is social science a real science?,” in which he noted that both Gramsci and Lukacs objected to Bukharin’s scientistic positivism because it obliterated Marx’s philosophy of praxis as creative human subjectivity as expressed in the “Theses on Feuerbach” and in the epigram, “Men make their own history.” Farmelant’s comments are useful as far as they go, but they left out an entire realm of the philosophy of the social sciences developed in the 1970s by Hanna Pitkin in Wittgenstein and Justice and Anthony Giddens in New Rules of Sociological Method and other studies. In these books, Pitkin and Giddens argue that the distinguishing feature separating the study of the social world from the natural world is that the study of society requires the observer to know the language and social meanings of the people they are studying. No such hermeneutic of understanding is involved in the study of the natural world. Nature doesn’t talk back. Also, as Pitkin demonstrated in her analysis of Max Weber’s concept of legitimacy, and which Giddens expanded on, there can be no separation of fact from value in the determination of whether social norms are legitimate or not, or whether they are being followed or violated. The epistemological status of the observations and comments of the social scientific investigator of social and political norms is on the same level as that of the subjects being studied. We are participants in the society we study. Drawn to a large degree from the philosophy of language and human agency associated with Ludwig Wittgenstein, J. L Austin, and John Searle, this theory of society as the skilled accomplishment of its members rejects any external theory of causality that treats people as “cultural dopes.”5 Rather than externally caused, human action in its essence is self-caused. In addition, as Alan Gewirth has demonstrated in Reason and Morality, the concept of human agency has a normative structure from which it is possible to derive the fundamental principles of universal human rights and justice.

However, it isn’t very helpful to start a conversation by telling the other party that they need to go and read a half-dozen books. If the discussion is going to be fruitful, these books will certainly have to be read eventually; but the primary purpose of the initial stage of such a discussion is to make a convincing case that these books should be read in the first place. I think the best way I can make this case is to give a personal account of how and why I came to read them myself. I see parallels between the political and moral questions that the New Left confronted in the 1960s and 1970s and the political and moral questions that the left faces today. Maybe my experience can clarify a few things.

The Barren Ethical Moonscape of Logical Positivism and the Philosophy of the Social Sciences in the 1960s.

The Port Huron Statement mentions briefly the disorienting moral and intellectual doctrine that governed academic life in the early 1960s:

The questions we might want raised—what is really important? Can we live in a different and better way? If we wanted to change society, how would we do it? —are not thought to be questions of a ‘fruitful, empirical nature,’ and thus are brushed aside.

The texts most commonly used to justify this separation of facts from values were A. J. Ayers’ Language, Truth and Logic and Max Weber’s two lectures, “Politics as a Vocation” and “Science as a Vocation.” Ayers’ short book was the most extreme, claiming that if a statement couldn’t be verified empirically, it was meaningless. Thus, the hard sciences were held up as the model of true “knowledge,” while the fields of normative political theory, ethics, and esthetics were dismissed as mere opinion. There is the irony that Ayers’ own “principle of verification” couldn’t be empirically verified either; but the prestige of the physical sciences was so powerful, and the desire to keep moral and political questions out of the social science curriculum so strong, values had a hard time finding a place in the academic bureaucracy. In addition, even the defenders of traditional humanistic values weren’t quite sure themselves how to answer the philosophical claims of the positivists that only observable facts and verifiable scientific laws constituted knowledge.

I entered Princeton in 1967 as a happy-go-lucky kid with the intention of studying physics and playing football. I wasn’t oblivious to the Bomb, racial injustice, or the Vietnam War, but my life wasn’t immediately disrupted by them either. The one thing that did affect me personally was that kids I had grown up with, and who didn’t go to college, were being drafted into the military. It wasn’t long before some of them came home seriously wounded, and some in body bags.

Just by chance, I was placed in a dorm across the hall from two sophomores who were also members of the small SDS chapter. They were also chemistry majors. So, we comprised a little group that was interested in science, math, politics, and morality; but Carl Hempel and his positivist philosophy of science and knowledge epitomized the strongly analytical tilt of the philosophy department. Two partial exceptions were Walter Kaufmann, who taught existentialism, and Richard Rorty, who was then transitioning to his own brand of pragmatism. It was in Rorty’s introduction to modern philosophy that I read Austin vs. Ayer on perception and first became acquainted with what was and is misleadingly called “ordinary language” philosophy.

But the question of whether moral judgments constituted knowledge of the real world or were just feelings and opinions was not just a problem to be decided in the seminar room. Opposition to the Vietnam war couldn’t wait on a philosophical resolution of the epistemological status of ethical statements. Consequently, for me, the study of science and academic philosophy soon took a back seat to the study of history and the social sciences. These studies were topped off in the fall of 1969 with Peter Winn’s in-depth seminar on the Cuban revolution, for which I wrote a paper on the lack of civil and political rights in the Marxist-Leninist theory of the one-party state, but without any practical conclusions about what the Cubans should do; and Jerrold Seigel’s comprehensive seminar in the spring on Marxism in Europe until Lenin’s death.

My main takeaways from the Marxism readings were much the same as those of C. Wright Mills’ short 1962 book, The Marxists. I read the first volume of Capital and agreed with Joan Robinson that the labor theory of value was incoherent and unworkable and that a secular decline in the rate of profit was a contingent possibility rather than a theoretical necessity. Likewise, the revolutionary historical mission ascribed to the proletariat by Marx was more political hope than scientific deduction. On the issue of science versus ethics, I found Marx confused and conflicted, Kautsky in over his head, and Engels somewhere in between. There are no laws of society similar to the laws of nature. Marx knew this, as evidenced by his retention of his early philosophy of creative human subjectivity, but Kautsky and other Second International orthodox Marxists forgot about this subjectivity in their dispute with the neo-Kantians. However, the neo-Kantians themselves didn’t get historical subjectivity right either, as George Lichtheim explained well enough in Marxism. Then again, the critical theory-influenced neo-Hegalianism of Lichtheim and Herbert Marcuse (in Reason and Revolution) was also inadequate. The positive side of Marxism was, of course, its world-spanning historical, political, and economic investigations, coupled with “the most formidable, sustained and elaborate indictment ever delivered against an entire social order.”6

I never wrote a paper for the Marxism course because the invasion of Cambodia and the shootings at Kent State triggered a national student strike that shut down the universities. My next move was to join the Revolutionary Union and begin working-class organizing.

Democracy vs. Science in the New Communist Movement

I have written about my time in the RU in other places and will only highlight here how my reading of Lenin on democracy led me back into a consideration of the philosophical basis of democratic ethics. The main sequence is:

- The invasion of Cambodia convinced many New Leftists that a wider war was in the works, risking a major confrontation with China. Some five to ten thousand New Left activists then began to move into working-class areas and form independent collectives or join one of the existing revolutionary Marxist groups in order to prepare for the wider conflicts to come;

- On the other hand, the term “Marxist” should not be taken too literally. In the year before the Cambodian invasion, SDS members generally described the organization as an “anti-racist, anti-imperialist, pro-working class student organization,” and only a small number had actually taken up working-class activities, mainly in the GI coffeehouse projects and in strike support. The ideologue-leaders of the main New Communist groups did write manifestos aligning themselves with the Marxist-Leninist-Maoist tradition, but these groups numbered only a few dozen members in 1970 and none had a newspaper or any worked out idea for mass political activity; so the meaning of this “Marxism” was mainly emotional and theoretically thin, though gaining familiarity with the esoteric language of the Chinese Communist Party, its dispute with the Soviet Union, and the meaning of the Cultural Revolution took a lot of work;

- In order to assimilate the large influx of post-Cambodia recruits into some kind of political activity, apart from just getting a factory job, the RU hit upon the idea of starting local, monthly “anti-imperialist working-class newspapers.” Our paper in the Oakland-Berkeley-Richmond area was called “People Get Ready.” Neither explicitly Marxist nor socialist nor publicly identified with the RU, writing, producing, and selling the paper at factory gates and on the street kept us busy. Although the paper was mostly a waste of time and effort, it was in the course of writing an article on George Jackson’s death that the RU leader of the paper suggested I read an article by Lenin from Iskra titled, “The Drafting of 183 Students into the Army.” That article led me to an understanding of Lenin’s democratic ideology and goals that are now more widely known through the work of Neil Harding and Lars Lih.

- By 1973, the New Communist Movement was entering its “party building” phase, a Wile E. Coyote moment because the Vietnam war was ending and the US-China agreement was pulling the rug out from under the expectation of a new world war.7 I disagreed with the RU’s unreconstructed Leninist party proposal based on my reading of Lenin, an opposition that called forth all the typical democratic centralist responses. I was not allowed to circulate papers outside my own collective, while leadership heavies would descend on our meetings to win back those sympathetic to my arguments. Although an absurdly insignificant incident in the scale of things, I nevertheless felt that a right to discuss my views with others in the organization had been violated. You take your lessons about life where you find them, and this little bit of heavy-handedness made me think about the relationship between power and rights in general. Another little interesting feature about this encounter is that the leader who found it necessary to come to our collective later co-wrote a pamphlet, “Important Struggles in Building the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA.” Discussing various petty-bourgeois deviations, the pamphlet identified in particular the “new left tendency” of “seeing communism…not as the revolutionary science and the historic goal of the proletariat, but in Utopian terms of ideals like ‘democracy,’ ‘equality’ and so on.”8 Ever since then the words “Marxism is a science” stick in my craw.

Democratic Ethics and the Philosophy of Language

After leaving the RU, I didn’t immediately go looking for a philosophical basis for a democratic ethic. I mainly talked to anyone who would listen about Lenin’s theory and practice of political agitation in Iskra, his advocacy of the goal of a democratic republic, the continuing relevance of this goal for us in the US, and how What Is to Be Done? had been misleadingly used for decades as a justification for a centralist “party of a new type.” There were enough unaffiliated radicals floating around the Oakland-Berkeley area to pull together a couple of study groups to discuss these issues, but to little effect. Meanwhile, the party-building circus continued to play itself out.

Then, while on a trip with my girlfriend to visit her relatives in Los Angeles, I had a conversation with one of her cousins, who was studying ethnomethodology with Harold Garfinkel. I had no idea what ethnomethodology was, so he gave me a capsule summary. I’ll just use a few selections from Wikipedia to give a sense of ethnomethodology’s distinctive approach to the study of social conduct:

Ethnomethodology is the study of how social order is produced in and through processes of social interaction…. Ethnomethodology is a fundamentally descriptive discipline which does not engage in the explanation or evaluation of the particular social order undertaken as a topic of study…. For the ethnomethodologist, participants produce the order of social settings through their shared sense-making practices. Thus, there is an essential natural reflexivity between the activity of making sense of a social setting and the ongoing production of that setting.

Garfinkel was criticized by other sociologists for producing trivial and uninteresting micro-studies of everyday social life, but his project had deep philosophical and sociological aims. First, he disagreed with Talcott Parsons’ functionalist sociological theory that social order was maintained by the inculcation of a society’s dominant cultural values in the society’s members, that people internalized and acted out “roles” in a script written by others. Garfinkel held that if there were roles and scripts, they were written and acted out by the members of society themselves in creating the very social milieu which they themselves inhabited. Think of Cosmonaut or the Marxist Unity Group creating their own existence. Philosophically, Garfinkel’s appreciation for the complexity and use of ordinary language in constituting the social world stood in contrast to what he saw as an arrogant and dismissive attitude in mainstream philosophy and sociology toward the adequacy of natural language to account for the production and reproduction of social life by its members.

I confess I found the concepts of ethnomethodology a little bewildering and too abstract to fully understand at the time. The best I could do was to relate my recent experience in the RU of trying to write articles in our newspaper and union caucus newsletter that people would read, of Lenin’s creation of and writing for Iskra in order to pull together and focus scattered political forces, and the similar debates in the New Communist Movement about how to approach the problem of party-building. These political examples did not fully fit within the parameters of ethnomethodology because they were not limited to descriptions of social processes but involved conscious efforts to shape and move them in a particular direction. They did, however, involve close attention to the uses and persuasive power of language in contrast to the stupefying dogmatism of the leaders of the main communist groups and their utter disinterest in persuading anyone of anything (outside of a small group of loyal followers). Cousin David, after listening patiently to my effort to understand what he was talking about, suggested I read Wittgenstein and Justice by Hanna Pitkin.

Wittgenstein and Justice is impossible to summarize because it, like the philosophy of language that it seeks to elucidate, consists primarily of particular examples of how language actually operates, how complex and variegated it is, and how many social functions it is used to perform. All I will do here is give a summary of Pitkin’s linguistic analysis of the concept of political legitimacy, a central concept in political science and sociology deriving primarily from Max Weber. Pitkin begins:

The notion of legitimacy was, so far as I know, first ‘cleansed of subjectivity’ and redefined for social scientific use by Max Weber, though, as usual in such a process, Weber did not intend any substantive redefinition. By now, Weber’s definition of ‘legitimacy’ has become common currency in most of the social sciences, so its vicissitudes form a story of considerable general significance.9

Pitkin then goes to the dictionary definition of legitimacy to get a general sense of how the word is used in everyday language, a common beginning step in “ordinary language” linguistic analysis. In general, legitimacy means “being in accordance with law or principle” or with “the laws of reasoning.” Legitimacy is not a matter of personal preference, or taste, or simple direct perception. Claims of legitimacy rest on appeals to foundations external to and independent of mere assertion or opinion. “Like ‘justice,’ the term ‘legitimacy’ invokes standards, and thus resembles neither ‘green’ nor ‘delicious.’”

Weber found this normal, dictionary definition of legitimacy unsuitable for his purposes because it entailed the public discussion and determination of whether actions or states of affairs in the world conformed to publicly recognized values, rules, and procedures. Weber deemed any discussion or judgment of public affairs inherently “subjective” and sought to purge this “normative” content from his “empirical,” “scientific” concept of “legitimacy”:

As [John} Schaar points out, the normal meaning of ‘legitimacy’ implies some standards external to the claimant, but Weber’s definition dissolves legitimacy ‘into belief or opinion…. By a surgical procedure, the older concept has been trimmed of its cumbersome ‘normative’ and ‘philosophical’ parts,’ so that the sociological ‘investigator can examine nothing outside popular opinion in order to decide whether a given regime or institution or command is legitimate or illegitimate…. In seeking to insulate the sociologist from the context of judging and taking a position, Weber in effect made it incomprehensible that anyone might judge legitimacy and illegitimacy according to rational, objective standards…’

By now, Weber’s definition has become more or less standard jargon in social and political science…. Thus, an uninitiated student dropping in on the middle of a modern political science course may be startled to hear such propositions as that a government may become increasingly legitimate by the judicious and effective use of secret police and propaganda. Which seems about as accurate as that one can increase the validity of an argument by threatening to shoot anyone who disagrees.

Pitkin’s analysis of the corruption of language and the attempt to delegitimize and limit the study and discussion of political ethics in the social sciences has had a significant influence on the thinking of other social theorists. Gavin Kitching acknowledges a debt to Pitkin in Karl Marx and the Philosophy of Praxis and Marxism and Science: Analysis of an Obsession, and Anthony Giddens adopted and extended Pitkin’s analysis of Weber and legitimacy in his study of Weber’s theory of conflicting “ultimate values” in the larger society as a whole. Giddens’ comments are the more relevant here.

Giddens reviews Weber’s insistence that facts about the social world and moral evaluations of the social world do not overlap, Weber essentially repeating the long-established philosophical position of both Hume and Kant that there is a logical disjunction between the “is” and the “ought.” Among the “oughts,” Weber held that there can only be a conflict between mutually incompatible “ultimate values.” The problem, as Giddens explains by reference to Pitkin’s analysis of legitimacy, is that having values is not the same as just having personal whims. Values, or at least values that have some bearing on the lives of others in society, have to be justified in public. The practice of public accountability, like the rules of language themselves, cannot just be dispensed with as a nuisance. They are one of the means by which social life is carried on. Giddens observes:

It is an elementary qualification to point out that an unprincipled rejection of the need or possibility of rationalization is irrelevant here. A person can of course reject any knowledge-claim, by simply refusing to accept a claim of reasoning while not offering counter-arguments of his own.10

From the standpoint of society, however, such a dogmatic refusal to offer justifications for one’s beliefs and actions is itself a political act, an act of moral and political irresponsibility. Rationality, contrary to what Hume and Weber claimed, is not just limited to the rationality of finding the means to achieve arbitrary personal ends. There is also the collective rationality of the public moral language of justification and legitimacy.

Underlying Pitkin’s and Giddens’ social and political theorizing is the concept of human agency. Agency is the human power to initiate action, make choices, explain, argue, make claims, demand rights, issue commands, etc. However, they don’t develop a particular theory of rights and justice of their own out of the concept of agency. They are content to operate within the parameters of the taken-for-granted rights of free speech and public debate that already obtain within modern liberal societies. They therefore generally limit themselves to a kind of procedural argument that holds that, whatever political issue may arise, the concept of legitimacy requires that it must be subject to public discussion and evaluation. Alan Gewirth took the concept of agency and built a more definitive moral and political theory on it.

In a series of studies that culminated in his Reason and Morality11, Gewirth did not assume that agents already possessed the rights generally prevailing in a modern liberal society. He asked the more fundamental question of what rights and powers must a human agent have in order to be a human agent. Of course, the Declaration of Independence famously declared that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness;” but gifts from God don’t carry much weight in philosophical circles these days. Gewirth took this question of the foundation and origin of rights and asserted that agents themselves must out of necessity demand rights from society and have access to society’s resources in order to live. Gewirth’s beginning point is different than Rawls’. Rawls made his agents ignorant of their own position in society and asked what rules of justice a rational agent would choose in order to be protected from bad luck, a procedure that always struck me as resembling the standpoint of an insurance company actuary or social welfare administrator more than that of a political philosopher. Gewirth placed his agent in a situation without rights and asked what that agent must demand from society and what could possibly justify any departure from equality. The “must” in Gewirth’s argument is both logical and practical. It doesn’t necessarily mean that demands for rights will be successful, but the only reason we have the language and reality of rights in the first place is that people have demanded them and thus created them.

I won’t go any further into the details of the specific political and economic rights and obligations that Gewirth deduced from his principle of generic human equality. I’ll just say that for my money Gewirth developed a philosophical foundation for the existence of universal human rights from which it is possible to draw democratic and socialist conclusions. For another reference, John Searle has also developed a similar logic-of-language theory of human rights in Making the Social World: The Structure of Human Civilization, in which he answers the skepticisms of Hume, Bentham, and MacIntyre.12

Marx, Justice, and Rights

Now we come to the bizarre problem of the relationship between Marxism and democratic rights. I say bizarre because in the 1840s Marx and Engels were active supporters of the Chartist movement in England, fought for a democratic republic in Germany in 1848, and were life-long advocates of the democratic republic as the state form of working-class rule. Yet Marx regularly fulminated against the concepts of rights and justice, called rights bourgeois in their essence, and in the Critique of the Gotha Programme even claimed that compensation in the first stage of communism based on the amount of work performed was still a bourgeois right. Many have tried to explain these seemingly contradictory statements by Marx, with mixed results. Norman Geras’ “The Controversy About Marx and Justice”13 is the best explanation I have run across of what Marx was up to.

There is a double dislocation in Marx’s conception of rights and justice. First, Marx did not think that democracy was a matter of rights and justice, as Tom Paine, the Jacobins, the Chartists, and other natural rights theorists believed, and, second, Marx did not believe that the proletariat’s expropriation of the capitalists and the establishment of socialism would end the era of bourgeois right. Only communism, based on need rather than right, would leave the psychology of personal self-interest behind. How did Marx try to justify this highly idiosyncratic conception of rights and justice? First, he narrowed the conception of rights in such a way as to exclude the positive power of democratic rights to limit or abolish oppressive, anti-social forms of private property, efforts that actually took place during the French Revolution. This narrowing of the conception of rights is stated most clearly by Marx in “On the Jewish Question,” where the rights of man and citizen are characterized as entirely egoistic. Then, when Marx envisions the possibility of the citizen seeking to overcome bourgeois egoism, he does not put this in the language of democratic rights being exercised for the common good, but in the language of “species-being”:

Only when the real, individual man re-absorbs in himself the abstract citizen, and as an individual human being has become a species-being in his everyday life, in his particular work, and in his particular situation, only when man has recognized and organized his ‘own powers’ as social powers, and, consequently, no longer separates social power from himself in the shape of political power, only then will human emancipation have been accomplished.

Here we see Marx separate social powers from political powers. But how are citizens supposed to exercise their social powers except through democratic political power? Marx fudges this issue and separates himself from the language of standard democratic theory.

Marx is aware that he is creating a new language of human liberation and seeks to justify it by claiming that the movement of the proletariat is a new and unique historical force in no need of moral justification:

Thus, in The German Ideology: ‘Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things.’ Similarly, twenty-five years on in The Civil War in France, the workers ‘have no ideals to realize, but to set free the elements of the new society with which old collapsing bourgeois society itself is pregnant.’14

Can this work? Can Marxists actually carry out mass political work without invoking the language of rights and justice? It seems not. Marx himself, in the only mass working-class organization he ever participated in, had to use the language of rights and justice in his official writings for the International Workingmen’s Association, complaining in a letter to Engels that “I was obliged to insert two phrases about ‘duty’ and ‘right’ into the Preamble to the Rules, ditto about ‘truth, morality and justice’, but these are placed in such a way that they can do no harm.” The same was true of his Inaugural Address and Letter to Lincoln. This question about what practical political language Marxists should use in their mass literature was settled for me by reading Lenin on political agitation and the democratic republic. One may believe in the historic mission of the proletariat, but that mission will have to be carried out in the language of democratic rights and the goal of a democratic republic.

Final Comments

Since Llorente’s article was posted on 12/19, two other articles touching on the subject of socialism and democracy have been published by Cosmonaut: “Why Bordiga Got Democracy Wrong” by Daniel Melo and “Letters: Bordiga and the Bathwater” by Parker M. Shea. While in spirit I’m on the side of Melo against Shea, Melo actually shares misconceptions with Shea and Llorente about the content and history of democracy that undermine the very argument he is trying to make. Shea zeroes in on Melo’s misconceptions in order to cast doubt on the usefulness of democracy and ends up supporting Llorente.

To repeat, the US is not a democracy. Ever since Tom Paine and the French Revolution, democracy has meant sovereignty of the people expressed through universal and equal suffrage in a single representative body: no President, no Senate, and no Supreme Court with the power to overturn legislation. The bourgeoisie has always hated democracy, and it is a conceptual and historical absurdity to think that the words “bourgeois democracy” represent anything in the real world, regardless of their Marxist pedigree. Democracy and capitalism have been in open conflict for more than two centuries. It is only in western Europe after WWII that genuine representative democracy gained a foothold, most thoroughly in Scandinavia, and then only within the overarching US empire. The US itself remains an oligarchic monstrosity without a democratic system of representation, as was the Italian constitutional monarchy in the time of Bordiga. Llorente, Melo, and Shea seem oblivious to these historical and political realities and operate in a fantasy land that equates any voting system at all, no matter how unequally the votes are weighted, with democracy. They think parliament means democracy. They are lost before they even begin.

Because Melo thinks democracy already exists, he gets caught in the trap of trying to come up with a conception of “actual democracy” that can thread the needle between the “façade” of bourgeois democracy and a Stalin-like denial of democracy. In the course of his search, he makes several conceptual missteps. First, in one clumsy paragraph, he suggests that capitalists have a democratic right to veto any attempt to strip them of their ownership and control of the means of production, yet in the next paragraph he retracts this conception of democratic right and asserts that the capitalists have never had any legitimate democratic right to monopolize the means of production in the first place. Shea seizes on the first formulation, but only the second is coherent and sustainable. Second, Melo introduces a concept of justice by a theorist named Forst. While different than Rawls’ concept of protecting the unlucky, Forst nevertheless seems to start with an ahistorical concept of justice from which he then derives the necessity of democracy. This formal deduction of the need for democracy from a concept of justice is the reverse of C. B. Macpherson’s historical approach of investigating how democratic conceptions of justice arose in the course of political struggles for democratic rights, an approach that I find much more useful. Third, Melo lands himself in a muddle when he seems to accept Bordiga’s rejection of democracy as a metaphysical delusion: “Bordiga is right to note that the mere imagining of democracy, the ‘proclamation of the moral, political, and juridical equality of all citizens,’ was (and is) wholly insufficient to bring about actual equality.” Lenin remarks in State and Revolution that this kind of static juxtaposition of abstract concepts cannot capture “the dialectics of living history”:

To develop democracy to the utmost, to find the forms for this development, to test them by practice, and so forth— all this is one of the component tasks of the struggle for the social revolution. Taken separately, no kind of democracy will bring socialism. But in actual life democracy will never be ‘taken separately’; it will be ‘taken together’ with other things, it will exert its influence on economic life as well, will stimulate its transformation; and in its turn will be influenced by economic development, and so on. This is the dialectics of living history.

Lastly, Shea picks up on Melo’s unfortunate phrase of “pulling them [capitalists] into the democratic framework” and asks how such a conception of democracy is compatible with socialism. I said near the beginning that it is possible to draw a parallel between the position of ex-capitalists in a democratic polity that has socialized the means of production and the position of ex-slaveholders in the South after the abolition of slavery. The emphasis must be placed on the “ex,” otherwise only confusion will prevail. Melo doesn’t state directly that the capitalists he is pulling in are ex-capitalists, and Shea catches the oversight. To take the example of the ex-slaveholders, it wasn’t freedom of speech and the freedom to organize political parties that gave them power. It was only by the organization of terror and the denial of civil and political rights to the ex-slaves that the ex-slaveholders were able to regain any semblance of their former power. The same would be true of dispossessed capitalists. Dispossessing capitalists of the means of production is not a violation of their democratic rights because they have no such right. Nor is it necessary to deny them normal civil and political rights after they have been dispossessed of their economic resources. However, if they resort to forming illegal gangs and engage in terrorism and sabotage, that’s another matter; but suppressing terror is not a violation of democratic rights, it is protecting the democratic rights of the majority.

- Mike Macnair, “Marxism and Theoretical Overkill,” Weekly Worker, 1/20/2011.

- Mike Macnair, “Modern and Ancient Constitutions,” Weekly Worker,” 10/28/2021.

- Letter, “Democracy,” Weekly Worker, 11/4/2021

- Donald Parkinson, “Faith, Family and Folk,” Cosmonaut, 12/28/2019.

- Harold Garfinkel used the term “cultural dope” to characterize the attitude of standard sociological theory, particularly Talcott Parsons’ functionalism, toward the individual social actor. It can also refer to mechanistic or dominant-ideology forms of Marxism.

- Isaiah Berlin, quoted in C. Wright Mills, The Marxists, p. 95 (Dell Publishing, NY) 1962.

- Franz Schurmann, The Logic of World Power, (Pantheon, New York) 1974, is still the best guide to China’s and the US’s strategic realignment.

- Bill Klingel and Joanne Psihountas, available at marxists.org.

- Hanna Pitkin, Wittgenstein and Justice, (University of California Press, Berkeley) 1972, p. 280. All additional quotations are drawn from pp. 280-84.

- Anthony Giddens, Studies in Social and Political Theory, (Basic Books, New York) 1977, pp. 89-95.

- Alan Gewirth, Reason and Morality, (University of Chicago Press, Chicago) 1978.

- John Searle, Making the Social World, (Oxford University Press, Oxford) 2010, Chapter 8.

- Available at marxists.org

- Quotation from Geras.