In my 5/8/2022 reply to Père Duchesne, I made several interrelated points about the relationship between liberalism and democracy. Historically, as both a political movement and a political philosophy, liberalism emerged in the English Civil War as a challenge to the divine right of kings. The Parliamentary forces demanded legislative supremacy over the Crown and the codification of a Bill of Rights that guaranteed essential voting and civil rights. However, within the Parliamentary forces there was a dispute between Cromwell and the Levellers over the amount of property required to qualify as a voter in parliamentary elections. The Levellers were not deceived by Cromwell’s arguments for a high property qualification; they were physically crushed. Some were executed, some were driven out of the army, and others fled into exile, but their ideas of a broader popular political sovereignty did not die. They survived in popular memory and culture, in the beliefs and practices of various dissenting Protestant denominations, and in some of the political communities of colonial North America. During the American and French Revolutions, the Levellers’ belief in equal and universal natural rights was revived and broadened to encompass the demand for equal voting rights for all. That movement was also defeated, only to rise again in the Chartist movement in England in the 1830s and ‘40s, where Friedrich Engels, in The Condition of the Working Class in England, combined for the first time the political demand for a democratic republic with the socialist idea of public ownership and management of the new powers of industrial capitalism. Through all of these historical changes and upheavals, the one constant of liberalism as a political movement was its claim to a right of unlimited accumulation of private property. When that property interest was threatened by autocrats, liberals championed republican rights and institutions and sought to win small-property owners and propertyless wage-workers to their side. However, when popular forces grew too powerful and threatened the concentration of property, large property owners abandoned republican principles and sought the protection of the military and police, leaving only the working class as a consistent defender of liberalism’s original commitment to republican political rights. I then cited Lenin’s proposition that “The political demands of working-class democracy do not differ in principle from bourgeois democracy, they differ only in degree” to argue that universal and equal voting rights was the line of demarcation between a liberal republic and a liberal-democratic republic, and that the principle of universal and equal voting rights was derived directly from the theory of universal and equal natural rights to life, liberty, and the consent of the governed originating in the English Civil War. In this response, I will simply take Lenin’s (and other Marxists’) conception of the liberal-democratic republic as the working-class’ principal political goal and prospective form of state rule and compare it to the alternative conceptions offered by Llorente, Dalrymple, and R. A.

Llorente’s Continuing Muddle

It is true I dismissed Llorente’s first article as confused and obtuse in a few paragraphs and then moved on to my own view of the content and philosophic justification of liberal-democratic rights. Llorente took offense at this cursory dismissal, and in his reply, “Endless Muddle: Gil Schaeffer on Democracy, Socialism and Liberal-Democratic Rights,” doubled down on his original assertion that the US is a liberal democracy and that the question of the undemocratic structure of the Constitution has little or no bearing on a discussion of socialist theory and strategy. On the goal of a democratic republic in the theory and programs of classical Marxism, Llorente remained silent: the words “democratic republic” do not appear in either of his articles. Nor does Llorente believe that the statement in the Communist Manifesto that “the proletarian movement is the self-conscious, independent movement of the immense majority, in the interest of the immense majority” provides an adequate basis to conclude that the establishment of the rule of the working-class is simultaneously the establishment of a system of universal democratic rights. He rejects this association because some (unnamed) political theorists deny “that a particular class, stratum, sector, etc., of society is uniquely entitled to run the economy and society.” Against this form of political theorizing, I’ll quote from Engels’ Principles of Communism, No. 18, “What will be the course of this revolution?”:

Above all, it will be to establish a democratic constitution, and through this, the direct or indirect dominance of the proletariat. Direct in England, where the proletarians are already a majority of the people. Indirect in France and Germany, where the majority of the people consists not only of proletarians, but also of small peasants and petty bourgeois who are in the process of falling into the proletariat, who are more and more dependent in all their political interests on the proletariat, and who must, therefore, soon adapt to the demands of the proletariat. Perhaps this will cost a second struggle, but the outcome can only be the victory of the proletariat.

The key words are “through this.” By establishing a democratic constitution, the working class, the immense majority, becomes the dominant political force in society and controls the “means for putting through measures directed against private property and ensuring the livelihood of the proletariat.” Engels’ explanation of how the rule of the working-class is simultaneously a system of universal democratic rights seems perfectly clear to me. The majority makes the laws that apply universally. Democracy and the class struggle are not two different things but two different descriptions of the same thing: the struggle for democracy is the political form of the class struggle.

Next, Llorente asks why we should take the French Revolution’s and Tom Paine’s definition of democracy as “sovereignty of the people expressed through universal and equal suffrage in a single representative body: no President, no Senate, and no Supreme Court with the power to overturn legislation” as the only correct definition when C. B. Macpherson thought otherwise. My answer is that is what the Chartists thought, what Marx and Engels fought for in the 1848 revolutions, what the Radical Republicans wanted in Reconstruction, what Marx thought the Commune had established, what Engels thought should have been expressed more forcefully in the Program of the German Social Democratic Party, what the Russians did put into their Program, and what the American Socialist Party also put into their 1912 Program. As much as I admire and have learned from Macpherson’s historical and theoretical writings, that does not entail going along with all his political characterizations of mid-twentieth century liberal capitalist republics. Llorente thinks that saying the US is not a democracy is theoretically and politically sterile and prefers using Macpherson’s and Frank Cunningham’s “degrees-of-democracy” approach in order to avoid “conundrums” in analyzing political rights. Llorente says he assumes I believe that citizens of the US “enjoy a full array of liberal-democratic rights” and then asks how it is possible to enjoy democratic rights in an undemocratic country. Isn’t that a contradiction? I gave my answer to this possible conceptual puzzle in the letter to Père Duchesne: the rights that Llorente calls liberal-democratic rights are actually liberal republican rights, not full democratic rights. Only universal and equal voting rights qualify as democratic rights. All the other liberal rights commonly called democratic are necessary for and incorporated in a democratic republic, but by themselves do not add up to democracy. Hence, no conundrum. It is certainly possible to rank political systems on a scale from autocratic to democratic, but, again, that would mostly be a scale of liberal republican rights up to the point of transition to democracy. The Scandinavian countries definitely qualify as democratic republics, and on every measure of working-class organization, public ownership, market regulation, income equality, social welfare, trust, and political participation consistently rank near the top of international scales, so much so that Matt Bruenig thinks some of them actually do qualify as socialist. I don’t go that far. They are small countries subject to larger economic and political forces over which they have little control. Llorente comments that the example of the Scandinavian democracies proves that either capitalism is compatible with some forms of democracy, or those countries have not achieved democracy. This either/or comment is too glib. As Engels wrote in A Critique of the Draft Social-Democratic Program of 1891, “If one thing is certain it is that our party and the working class can only come to power under the form of a democratic republic. This is even the specific form of the dictatorship of the proletariat, as the Great French Revolution has already shown.” However, the establishment of a democratic republic doesn’t mean that socialism can be introduced in one stroke. In the Critique of the Gotha Program, Marx held that “it is precisely in this last form of state of bourgeois society [i.e., the democratic republic] that the class struggle has to be fought out to a conclusion,” and “Between capitalist and communist society there lies a period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.” It is too much to ask a small country to carry out this transition on its own. If we in the US can accomplish what the Scandinavian countries have achieved in transforming their political institutions, we will be in a much stronger position to carry the transition to socialism through to completion.

In addition to whatever disagreements we may have regarding the character of current political systems with capitalist economies, Llorente and I also disagree about how to talk about rights. He thinks socialism demands a post-liberal-democratic conception of rights and I think socialism should be conceived of as the fulfillment of liberal-democratic rights. This is not just a political disagreement but a conceptual one as well. In my criticism of Llorente’s article, I made a passing reference to the Declaration of Independence’s invocation of self-evident, equal, and inalienable rights and some recent efforts to derive those rights from the philosophies of language and action associated with Wittgenstein, Austin, and Searle. Llorente dismisses these philosophical considerations as uninteresting and irrelevant, but I think it is impossible to talk about rights without entering into an examination of the origin and content of the language and claims of natural right in the English Civil War and in Locke. Llorente knows that Macpherson discussed these issues in The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism, but apparently believes they are now unimportant because he assumes liberal-democratic political rights have been achieved. He backs up his position by pointing out that Macpherson believed the same. I disagree with both Llorente and Macpherson on this. I attribute the assumption that the US is a liberal democracy to the extraordinary history of the twentieth century involving Stalin, Hitler, the New Deal, WWII, and the Cold War. Even those who doubted that the totalitarian/democracy dichotomy adequately captured the era’s political complexity, such as Macpherson, still couldn’t break with the characterization of the US as liberal-democratic. It was only with Daniel Lazare’s The Frozen Republic: How the Constitution Is Paralyzing Democracy (1996) that this characterization began to be questioned seriously in political circles for the first time in many decades. Lazare’s breakthrough was soon followed by his own Velvet Coup (2001), Robert Dahl’s How Democratic Is the American Constitution? (2002), and Sanford Levinson’s Our Undemocratic Constitution (2006) in the wake of the Supreme Court’s direct intervention and suspension of the vote count in the 2000 presidential election. Maybe if Macpherson had lived longer, he would have changed his views on the nature of the US political system just as Dahl had. We’ll never know, but we can see in retrospect where Macpherson made a wrong turn. Instead of following the development of the Levellers’ natural rights beliefs in the democratic republicanism of Paine, the French Revolution, the Chartists, and Marxism, Macpherson assumed the liberal-democratic political revolution in the West had essentially been completed. He therefore chose to focus primarily on John Stuart Mill’s concern that the concentration of economic power under ostensibly liberal-democratic capitalism might deny the majority of the population the resources and opportunities to develop their interests and talents. Macpherson called his new conception of liberal-democratic developmental rights post-liberal in the economic/property-owning sense but not in the civil rights republican sense. All the traditional liberal rights of free speech, publication, religion, association, voting, and political representation would continue as before in Macpherson’s conception of a fully developed post-capitalist liberal-democratic society.

So, in order to bring consistency to how we use the term liberal-democratic, we have to distinguish between Macpherson’s liberal-democratic ethical theory of an equal right of all to develop their capacities; the position that liberal republicanism only becomes liberal-democratic republicanism when there are equal voting rights for all; and the Cold War-inspired attribution of the liberal-democratic label to what are only liberal republics à la James Madison, who stated clearly in Federalist No. 10 that he and his co-conspirators had created a republic and not a democracy, either direct or representative. I combine the first two uses of liberal-democratic and think the third is confused and politically debilitating. The confusion that plagues the third conception is evident in Llorente’s discussion of Macpherson’s proposition that “the essential ethical principle of liberal democracy” is the “equal right of every man and woman to the full development and use of his or her capabilities.” Llorente grants that “If this is what Schaeffer means by ‘liberal democratic rights,’ I have no quarrel with him, since he is referring to a commitment which, as Ellen Meiksins Wood once observed, we may plausibly identify with Marxism.” Well, of course that’s what I was referring to because that is the formulation for which Macpherson is singularly famous. However, even though Macpherson’s liberal-democratic ethical principle is similar to Marxism in its prescriptions for transforming capitalism into socialism, it should not be identified with Marxism because Marxism is not based on a theory of rights at all but draws its conclusions about the need for socialism from an analysis of capitalism’s economic contradictions. This difference causes the authors Llorente cites, Meiksins Wood and Andrew Levine, to reject the usefulness of Macpherson’s liberal-democratic ethical rights framework even though they grant its socialist content. They reject Macpherson’s use of the language of liberal-democracy because (1) they think it entails an incremental practice of reform rather than a Marxist conception of a revolutionary break with the existing social order, (2) because it is overwhelmingly the ideological language that the capitalists themselves have created in order to legitimize their domination, and (3) because it displaces the superior Marxist theory of the class struggle. In my view, none of these objections hold up. First, there is no necessary connection at all between Macpherson’s liberal-democratic ethical goal and the tactics that might be required to reach it, despite Macpherson’s own gradualist preferences. Second, the capitalists did not create democratic language and demands. Historically. it was small-property owners and the propertyless who demanded democracy. Third, the demand for democracy is the class struggle. In classical Marxism (and in Madisonian republicanism as well), the struggle for the democratic republic was the highest form of the class struggle and the form of the state through which the working-class (or the debtor class) would rule. Like Llorente, neither Meiksins Wood nor Levine mention or take into account the central place of the democratic republic in the history and theory of Marxism. The result is inconsistency and confusion in their understanding and use of the language of liberal-democracy. This inconsistency applies to Llorente as well. In the closing sentence of his final paragraph discussing Macpherson, he writes that “the generality of this right, or ‘ethical principle,’ is such that we can derive many different, specific rights from it, including rights essential for socialism, some of which would be incompatible with existing liberal-democratic rights.” Here, immediately after granting that Macpherson’s liberal-democratic theory denies any ethical right to the monopolization of a society’s resources by the few, Llorente then uses the same liberal-democratic rights language to characterize existing capitalist property rights, which are undemocratic in Macpherson’s liberal-democratic ethical terms. Macpherson’s ethical rights and the positive legal rights written into existing law are two different conceptual categories entirely, a distinction that Llorente, Meiksins Wood, and Levine obscure by using the same language to refer to both. This inconsistency leads Llorente in one part of his article to characterize my claim that “Dispossessing capitalists of the means of production is not a violation of their democratic rights because they have no such right” as a muddle, whereas in his discussion of Macpherson’s ethical theory he grants that the same claim is justified. Talk about a muddle.

The Comparison of Rosa Luxemburg’s “The Russian Revolution” to Reconstruction

Llorente’s neglect of the place of the democratic republic in the history and theory of Marxism and his inconsistency in the use of the language of rights spills over into his comments on the Civil War and Reconstruction. Similar inconsistencies in the understanding of rights and the establishment of a democratic political and economic system lie behind the criticisms of Dalrymple and R. A. I’ll answer each of these criticisms in turn.

My initial response to Llorente’s claim that socialism demands a new conception of rights to replace liberal-democratic rights was to cite Rosa Luxemburg’s criticism of Lenin’s and Trotsky’s justifications for the banning of newspapers, parties, and elections. I then suggested that the period of Reconstruction was the best historical example we have of an effort to establish a Luxemburg-like democratic economic and political system to replace a dispossessed ruling class. Llorente had dismissed Luxemburg’s arguments in a brief footnote, and even implied that Luxemburg later changed her mind about liberal-democratic rights and had swung over to Lenin’s and Trotsky’s views on the nature of revolutionary dictatorship.[1] I disagree with this assessment of Luxemburg and believe she was one of only a few who continued to uphold the classic Marxist strategy that combined a willingness to use force to overthrow the undemocratic political rule of the bourgeoisie with an equally strong commitment to establishing a true democratic republic as the means necessary for the transition to socialism. In his repeat defense of the need for a non-liberal-democratic conception of rights, Llorente makes no mention of Luxemburg; but there is no escaping her challenge. The only alternative to the principle of liberal-democratic socialism is bureaucratic-police socialism. There is no in-between.

To understand the full depth of Luxemburg’s comments on the Bolshevik Revolution, it is first necessary to point out how similar they are to Marx’s comment on Babeuf in the Communist Manifesto:

The first direct attempts of the proletariat to attain its own ends—made in times of universal excitement, when feudal society was being overthrown— necessarily failed, owing to the then undeveloped state of the proletariat, as well as to the absence of economic conditions for its emancipation, conditions that had yet to be produced, and could be produced by the impending bourgeois epoch alone. The revolutionary literature that accompanied these first movements of the proletariat had necessarily a reactionary character. It included universal asceticism and social levelling in its crudest form.

The difference is, in Russia the Bolsheviks found themselves in power. As good Marxists, the Bolsheviks themselves were painfully aware of Marx’s analysis of the French Revolution but were trapped by conditions of economic destitution and low productivity, the exact opposite of the conditions of economic abundance on which Marx premised his vision of socialism. Llorente ignores this economic dilemma and says his views on socialism have much in common with what he calls the tradition of “revolutionary Marxism” associated with Bolshevism.[2] Luxemburg’s view was that the Bolsheviks tried to make a virtue out of necessity and rewrote Marxist theory to make it conform to their tragic situation. Although sympathetic with their plight and appalled at the German Social-Democratic Party’s abdication of its international and revolutionary duties, Luxemburg could not go along with Lenin’s and Trotsky’s rejection of Marxism’s democratic core.

Because I am not sure how familiar people are with Luxemburg’s “The Russian Revolution,” I am going to quote from it extensively. Luxemburg was a brilliant writer, and summaries inevitably blunt the subtlety and force of her language. Better to hear from her directly. The first quote is the one that is similar to Marx’s comment on the economic and social constraints on Babeuf’s vision:

Clearly, not uncritical apologetics but penetrating and thoughtful criticism is alone capable of bringing out the treasures of experiences and teachings. Dealing as we are with the very first experiment in proletarian dictatorship in world history (and one taking place at that under the hardest conceivable conditions, in the midst of the world wide conflagration and chaos of the imperialist mass slaughter, caught in the coils of the most reactionary military power in Europe, and accompanied by the completest failure on the part of the international working class), it would be a crazy idea to think that every last thing done or left undone in an experiment with the dictatorship of the proletariat under such abnormal conditions represented the very pinnacle of perfection. On the contrary, elementary conceptions of socialist politics and an insight into their historically necessary prerequisites force us to understand that under such fatal conditions even the most gigantic idealism and the most storm-tested revolutionary energy are incapable of realizing democracy and socialism but only distorted attempts at either.To make this stand out clearly in all its fundamental aspects and consequences is the elementary duty of the socialists of all countries; for only on the background of this bitter knowledge can we measure the enormous magnitude of the responsibility of the international proletariat itself for the fate of the Russian Revolution. Furthermore, it is only on this basis that the decisive importance of the resolute international action of the proletariat can become effective, without which action as its necessary support, even the greatest energy and the greatest sacrifices of the proletariat in a single country must inevitably become tangled in a maze of contradictions and blunders.

Some of those contradictions and blunders, in Luxemburg’s view, involved peasant land policy and the nationalities question, but her main focus was on the relationship between democracy and dictatorship in the Marxist concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat. The Bolsheviks’ dissolution of the Constituent Assembly and Trotsky’s justification of it is the target of her first criticism of the Bolshevik’s new conception of dictatorship.

After granting that Trotsky’s argument that the original elections to the Constituent Assembly had taken place before conditions in the countryside had been transformed by the new Bolshevik regime, Luxemburg writes:

All of this is very fine and convincing. But one cannot help wondering how such clever people as Lenin and Trotsky failed to arrive at the conclusion which follows immediately from the above facts. Since the Constituent Assembly was elected long before the decisive turning point, the October Revolution, and its composition reflected the picture of the vanished past and not of the new state of affairs, then it follows automatically that the outgrown and therefore stillborn Constituent Assembly should have been annulled, and without delay, new elections to a new Constituent Assembly should have been arranged….Instead of this, from the special inadequacy of the Constituent Assembly which came together in October, Trotsky draws a general conclusion concerning the inadequacy of any popular representation whatsoever which might come from universal popular elections during the revolution….

Here we find the ‘mechanism of democratic institutions’ as such called in question. To this we must at once object that in such an estimate of representative institutions there lies a somewhat rigid and schematic conception which is expressly contradicted by the historical experience of every revolutionary epoch [such as the English and French Revolutions as well as the censorship-subjected Russian Duma]….

To be sure, every democratic institution has its limits and shortcomings, things which it doubtless shares with all other human institutions. But the remedy which Trotsky and Lenin have found, the elimination of democracy as such, is worse than the disease it is supposed to cure; for it stops up the very living source from which alone can come the correction of all innate shortcomings of social institutions. That source is the active, untrammeled, energetic political life of the broadest masses of people.

Luxemburg went on to make several more absolutist declarations of the necessity for democratic rights and institutions that appear indistinguishable from standard liberal democratic theory:

Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of one party—however numerous they may be—is no freedom at all. Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently. Not because of any fanatical concept of ‘justice’ but because all that is instructive, wholesome and purifying in political freedom depends on this essential characteristic, and its effectiveness vanishes when ‘freedom’ becomes a special privilege….Without general elections, without unrestricted freedom of the press, without a free struggle of opinion, life dies out in every public institution, becomes a mere semblance of life, in which only the bureaucracy remains the active element….

The negative, the tearing down, can be decreed; the building up, the positive, cannot…. Only experience is capable of correcting and opening new ways. Only unobstructed, effervescing life falls into a thousand new forms and improvisations, brings to light creative force, itself corrects mistaken attempts. The public life of countries with limited freedom is so poverty-stricken, so miserable, so rigid, so unfruitful, precisely because, through the exclusion of democracy, it cuts off the living sources of all spiritual riches and progress….

But What About the Exploiters? Freedom Even for the Exploiters?

The pro-Bolshevik rap against Luxemburg is that she was ill-informed while imprisoned during the war and changed her mind about the Bolshevik dictatorship after she was released in November 1918 and joined the revolution. Llorente makes this insinuation in his first article because Luxemburg wrote in “What Do the Spartacists Want?” that the proletarian masses should “smash the head of the ruling classes” like the god Thor used his hammer. However, Llorente fails to mention that Luxemburg made a sharp distinction in “The Russian Revolution” between the destructive tactics needed to break the reactionaries’ hold on power and the constructive tactics needed to rebuild society after the proletariat had secured political power. Her comments on this subject are not fully worked out or unambiguous, but they are serious and identify crucial problems of revolutionary reconstruction. Some relevant passages are:

As the entire middle class, the bourgeoisie and petty-bourgeois intelligentsia boycotted the Soviet government for months after the October Revolution and crippled the railroad, post and telegraph, and educational and administrative apparatus, and, in this fashion opposed the workers’ government, naturally enough all measures of pressure were exercised against it. These included the deprivation of political rights, of economic means of existence, etc., in order to break their resistance with an iron fist. It was precisely in this way that the socialist dictatorship expressed itself, for it cannot shrink from any use of force to secure or prevent certain measures involving the interests of the whole. But when it comes to a suffrage law which provides for the general disenfranchisement of broad sections of society, whom it places politically outside the framework of society and, at the same time, is not in a position to make any place for them even economically within that framework, when it involves a deprivation of rights not as a concrete measure for a concrete purpose but as a general rule of long-standing effect, then it is not a necessity of dictatorship but a makeshift, incapable of being carried out in life. This applies alike to the soviets as the foundation, and to the Constituent Assembly and the general suffrage law….We have always distinguished the social kernel from the political form of bourgeois democracy; we have always revealed the hard kernel of social inequality and lack of freedom hidden under the sweet shell of formal equality and freedom—not in order to reject the latter but to spur the working class into not being satisfied with the shell, but rather, by conquering political power, to create socialist democracy to replace bourgeois democracy—not to eliminate democracy altogether….

But socialist democracy is not something that begins only in the promised land after the foundations of socialist economy are created; it does not come as some sort of Christmas present for the worthy people who, in the interim, have loyally supported a handful of socialist dictators. Socialist democracy begins simultaneously with the beginnings of the destruction of class rule and the construction of socialism. It begins at the very moment of the seizure of power by the socialist party. It is the same thing as the dictatorship of the proletariat….

Yes, dictatorship! But this dictatorship consists in the manner of applying democracy, not in its elimination, but in energetic, resolute attacks upon the well-entrenched rights and economic relationships of bourgeois society, without which a socialist transformation cannot be accomplished. But this dictatorship must be the work of the class and not a leading little minority in the name of the class….

The tacit assumption underlying the Lenin-Trotsky theory of dictatorship is this: that the socialist transformation is something for which a ready-made formula lies completed in the pocket of the revolutionary party, which needs only to be carried out energetically in practice. This is, unfortunately—or perhaps fortunately—not the case. Far from being a sum of ready-made prescriptions which have only to be applied, the practical realization of socialism as an economic, social and juridical system is something which lies completely hidden in the mists of the future. What we possess in our program is nothing but a few signposts which indicate the general direction in which to look for the necessary measures, and the indications are mainly negative in character at that. Thus we know more or less what we must eliminate at the outset in order to free the road for a socialist economy. But when it comes to the nature of the thousand concrete, practical measures, large and small, necessary to introduce socialist principles into economy, law and all social relationships, there is no key in any socialist party program or textbook. That is not a shortcoming but rather the very thing that makes scientific socialism superior to utopian varieties….

With Luxemburg’s general framework of distinctions as background, we can now go down the list of objections to my Civil War-Reconstruction example.

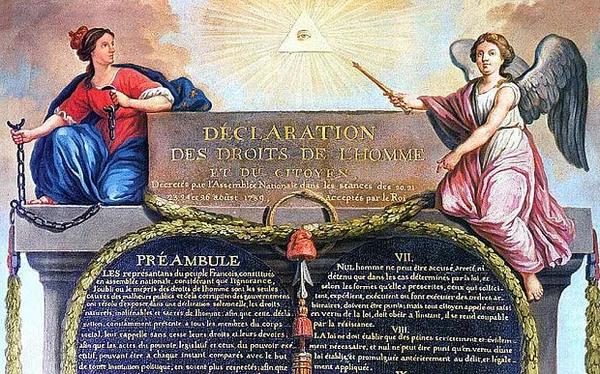

Llorente’s first criticism of my Civil War-Reconstruction illustration is that he thinks it is necessary to presume that the US was already a democracy in the late 1860s and early 1870s in order for it to have been in a position to attempt to establish democracy in the South. Wrong. The Radical Republicans knew the US political system as a whole wasn’t a democracy, and it couldn’t be as long as the Constitution remained as it was and the Southern land-holding and ex-slave-holding class retained political power. Their effort during Reconstruction was to transform the entire former undemocratic US slave republic, North and South together, into a democracy. They wanted to make a democratic revolution. That they failed in their attempt is not a reason to dismiss their effort. The Paris Commune failed too, but we still study those events for lessons about democracy. Second, Llorente finds fault with how I handle the relationship between constructing democracy and the exercise of rights. This problem is addressed in part in my previous discussion of the difference between moral rights and positive rights and in some of Luxemburg’s passages above. Since Llorente and his type of Marxist co-thinkers focus almost exclusively on positive rights and don’t seem to appreciate the importance of moral rights, he is bound to misinterpret what I say. The Civil War began as a conflict over the Constitutional right of the South to secede from the Union. The North saw secession as treason, a violation of both moral and positive right. As in the case of any crime, the effort to bring a criminal to justice is not a violation of the criminal’s rights, even if force is required to subdue them. Llorente seems to think that any time someone has to be restrained, confined, or punished for committing a crime they are having their rights violated or taken away. That is just a misconception of how rights work: there are no rights without the obligation to respect the reciprocal rights of others. Violate that principle and you forfeit your claim to the exercise of that right. This conception of the reciprocity of rights and obligations was spelled out in the 1789 French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, No. IV: “Political liberty consists in the power of doing whatever does not injure another. The exercise of the natural rights of every man, has no other limits than those necessary to secure to every other man the free exercise of the same rights….” Marx, although he expressed reservations about it privately to Engels, put the same concept of rights in the Constitution of the International Workingmen’s Association: “No rights without duties, no duties without rights.” The restrictions on the political activities of Confederate officials and the imposition of military rule in the South after the war were not violations of their rights. The Confederates committed crimes; their whole way of life was a crime; they had forfeited their rights; they earned their own punishment. Third, Llorente has a conception of a three-stage sequence beginning with capitalist society, a transition phase between capitalist society and socialist society, and a fully socialist society. In present day capitalist society, he thinks liberal democratic rights prevail; in the transition between capitalism and socialism, in what he calls the “pre-socialist phases of socialist construction,” he thinks that both the capitalists’ economic and political rights must be restricted; and in socialist society, after the capitalists have been fully dispossessed and no longer exist, society can operate without any limitation on the rights of speech, assembly, and political participation. Luxemburg slices up the transition period differently. Beginning with the revolutionary uprising, the workers do not hesitate to break “with an iron fist” the capitalists’ resistance and sabotage. In this phase of consolidating power, the conditions necessary for the functioning of normal civil and political rights do not exist. This is the destructive phase of the transition period. However, after power has been secured, the destructive period quickly passes over into a constructive period in which democratic political life must be instituted. To a degree which she does not specify with any precision, and which she argues cannot be specified with any precision in advance, this democracy will have to seek to integrate in the new society parts of the old society that opposed the revolution. In a section of “The Russian Revolution” not quoted above, Luxemburg pointed to the predicament the Bolsheviks found themselves in after securing power and their first experiments in worker self-management:

According to the main trend, only the exploiters are supposed to be deprived of their political rights. And, on the other hand, at the same time that productive labor powers are being uprooted on a mass scale, the Soviet government is often compelled to hand over national industry to its former owners, on lease, so to speak. In the same way, the Soviet government was forced to conclude a compromise with the bourgeois consumer cooperatives also. Further, the use of bourgeois specialists proved unavoidable….

The Bolsheviks’ response to this predicament was to make ad hoc deals with the former capitalists and bourgeois specialists, deals that could only lead to bureaucratic hierarchy and corruption. Although Luxemburg never specified who if anyone should continue to be excluded from political activity, it is clear she thought that only the widest possible democracy was capable of coping with the dilemma of needing the economic and technical skills of ex-capitalists and bourgeois specialists. Only the masses themselves were in a position to keep an eye on and contend with the educated classes; and the educated classes themselves, if they were going to contribute to the building of a new society, would have to be free to speak their minds and argue for what they thought was economically and technically necessary. Leaving decisions about such matters to unelected party, state, and military officials alone was a recipe for bureaucracy and corruption. It is this aspect of Luxemburg’s diagnosis of the difficulties of constructing a new social order that the period of Radical Reconstruction illustrates. The problem with Llorente’s conception of the transition period is that it focuses only on the destructive aspect of the transition, not the far longer and more complex job of constructing what Luxemburg called “the economic, social, and juridical system” of the new society. Eric Foner’s recent book, The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution, provides a good account of the Radical Republicans’ efforts in this direction; and Bruce Levine’s Thaddeus Stephens, which I haven’t read yet, is a new study of the Radical Republican leader who tried to turn the Civil War into a second American revolution.

Abner Dalrymple’s criticisms of my use of the example of Reconstruction are based on either a made-up story of things I didn't say or a switch in subject from my main focus on the aims of Radical Reconstruction to the causes of its loss of support. In his made-up story, Dalrymple aligns me with the Constitutional loyalism of Bernie Sanders, the Squad, electoral politics, and a commitment to amend the existing Constitution using the Constitution’s own amending procedures; but I do not even mention Sanders, the Squad, elections, or the amendment process in my article. He is mistaken. I am as much an anti-Constitutionalist as he is. Dalrymple then associates my supposed Constitutional loyalty with Reconstruction’s supposedly similar loyalty to the Constitution. But the Radical Republican vanguard of Reconstruction was hardly loyal to the Constitution at all. Like most abolitionists, they viewed the Constitution just as William Lloyd Garrison viewed it, as “a covenant with death and an agreement with hell.” They based themselves instead on the natural rights contained in the Declaration of Independence. However, because the Radical Republicans did not have the power to create a new democratic republican constitution on their own, they were forced to make the most of the political opportunities available to them. That is just practical politics, not Constitutional loyalty. Next, Dalrymple attributes the failure to carry Reconstruction through to the end to an overconcern with “the scruples of liberal democracy and adherence to the Constitutional path.” That’s the reverse of what happened. Reconstruction didn’t fail because the newly amended Constitution was followed too scrupulously, but because it wasn’t. His immediately following statement is closer to the truth: “White democratic rights were at odds with Black democratic rights, and the former tragically won out.” Putting aside the absurdity of calling the white denial of black rights “democratic,” this statement correctly recognizes the raw power at play. We agree that the Union took the boot off the neck of the defeated slave power too soon, but that is not what my original comments on Reconstruction were about. Like Llorente, Dalrymple focuses only on the destructive side of securing power in the South. My original disagreement with Llorente had to do with the nature of rights in the construction of a new democratic society after a revolution, an issue that Luxemburg examined in her criticism of the Russian Revolution and one that the Radical Republicans had to confront in practice. Political, military, police, and judicial power are necessary in both the destructive and constructive phases of the transition period. My point was about the nature of democracy and dictatorship in the constructive phase.R.A.’s Letter gets off on the wrong foot by bringing up the subject of “neokautskyism.” He seems to think my comments on Reconstruction derive in some way from something called neokautskyism, but then says he will not address this connection directly and will just focus on the deficiencies in my assessment of the postbellum era. Just to be clear, I am not a neokautskyist. I am a paleo-Tom Paine-ist. I see Marxism as a branch of democratic republicanism with some interesting but flawed ideas about economics, history, philosophy, and communism attached. Of the three sources and component parts of Marxism, English political economy, German philosophy, and French revolutionary republicanism and socialism, Marx and Engels critiqued and modified all three save for the democratic republic, retaining its principles unchanged from its origin in the French Revolution as the state form of the dictatorship of the proletariat. On Reconstruction in particular, R.A. thinks my approval of allowing ex-slaveholders back into the political system, as long as they respected the newly won rights of the ex-slaves and refrained from terror, was a doomed enterprise. His logic is that the terror they did in fact organize would not have been possible if they had not been allowed back into civil and political society in the first place. This logic is unassailable: if there is a chance someone might commit a crime, then crime can be prevented simply by excluding all potential criminals from participation in normal social life. As R.A. admits, in 1867 there was no way to distinguish between the white social clubs that would form the base of the future terroristic Klan and social clubs that would remain peaceful. R.A. leaves it to the reader to draw their own conclusion, but his implication is that all white social life needed to be restricted. The actual history of the period followed another path. As Klan terror grew after 1867, the Radical Republicans moved to counter it, and by 1872 the Klan had been crushed and the progress of Reconstruction reached its peak.[3] This progress was soon halted and then reversed, not because the policy of trying to integrate former rebels into a new multi-racial democracy was mistaken, but because the political will in the North to continue to enforce equal democratic rights for all weakened and eventually collapsed. There was no longer any will for either R.A.’s preferred policy of extreme civil and political repression or the actual Reconstruction policy of social and political integration combined with anti-terror enforcement. We have no disagreement on why this will collapsed, only on the issue of how to construct a post-revolutionary democratic society. I said of Llorente in my first article:

Absorbed in speculations about what measures might be needed during and after a violent revolution, Llorente has nothing to say about what we should be doing or saying in the meantime. I don’t think this absence of advice on how to conduct political activity in the here and now is an accident. It seems to be a general rule among Marxists that the more they focus on the necessity of violence in a future revolution, the less they are able to provide useful advice for current practice.

The same goes for the emphasis on the destructive side of the transition to a socialist society rather than on the need to develop the democratic power and institutions required for the construction of that society. That democratic power can only come from building a movement now based on democratic values and the goal of a democratic republic.

Liked it? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at submissions@cosmonautmag.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.