Francesco Sartor responds to last year’s debate on Italian Communist Party founder Amadeo Bordiga’s understanding of democracy with an analysis of his 1922 article ‘The Democratic Principle.’

Historical context

For some readers, it may be useful to become acquainted with Bordiga’s first years of activism as well as the historical context for when the 1922 essay was written and published before embarking in this debate. I tried here below to make an essential overview of both. For more daring readers I have published additional material both in English as well as in Italian available online.1

Amadeo Bordiga was born to a rather wealthy family with some aristocratic roots. His maternal grandfather, Count Amadei, his father Oreste Bordiga and his uncle were all Freemasons. This fact is important because Bordiga recalls that “his enrolment in the PSI [Partito Socialista Italiano] was a reaction to pressure being put on him to join the freemasons.” Instead, he joined the Italian Socialist Party in 1910 as a 21-year-old student of engineering.

I can very simplistically say that the PSI, founded back in 1892, had the ambition to structure itself on the German SPD image while emerging from the Milanese and the Romagnol experiences both heavily influenced by the French socialist movement. Filippo Turati, a sort of Italian Jean Jaurès, can be considered the real father of the PSI. He formed the Party with the Milan operaisti, Andrea Costa’s Romagna anarcho-socialists, and some radicals, mostly of Mazzinian republican origin who up to that moment had controlled the Italian Workers’ Societies. The radicals had an important role in the formation of the Mutual Assistance Societies and, most of their members being close to Mazzini and Garibaldi, were affiliated to the Freemasonry. If anything, the Marxist orthodox faction of the Party at that point was represented by the “Turatians,” and above all the Crimean Anna Kuliscioff.2

A clear turning point, after the Millerand affair in France,3 was the problem of socialist collaboration with the Zanardelli liberal Government in 1901. By then the Party was divided into three factions. The reformists, in favor of such collaboration; the intransigent faction, against; and the “integralisti” faction, for a “case by case” policy.4 By 1910 the reformists divided further into a left-wing, or “Turatians”, who were in favor of reforms without abandoning the maximal socialist revolution aim; and a right-wing, “Bissolatians” (i.e., the followers of Leonida Bissolati), who grew close to Bernstein’s revisionism and admired the British Labor Party model. While the integralisti and the biggest Confederal Union (CGdL) leaders had mostly been absorbed by the reformists; the intransigents, the faction that Bordiga would join, lacked charismatic personalities. It was led by the old “operaista” (i.e., workerist) Costantino Lazzari, and an emerging figure, Giovanni Lerda, whose leadership was short-lived as he was a Freemason. In the previous years the intransigents had been flirting with the syndicalist revolutionaries who, however, had left the party in 1907. Next to their intransigence against the collaboration with the Government, the intransigents opposed the electoral blocks and the presence of Freemasons in the Party. These were the battles that Bordiga engaged in during his first years in the Party.

In April, 1912, “Bordiga founded the ‘Circolo Carlo Marx’ (i.e., Karl Marx’s club) aiming at propaganda activity and the study of Marxist writings.” Up to that moment, the old generation of intransigents had mostly been linked to either the “operaisti” (i.e., workerist) or anarcho-socialist traditions; with very few exceptions, the “real” Marxists generation amongst the intransigents emerged around figures like Bordiga, Gramsci, Tasca, Terracini, and Togliatti.

Bordiga’s position towards electoral activity was at first one of tolerance, because he saw it as proselytism and propaganda, “but his distrust of the electoral system grew as the PSI suffered recurring defeats in elections despite the considerable effort it put into them”. His July, 1913 article in Avanguardia set a clear milestone in Bordiga’s thought on electoral action. The trigger was a recently translated book, Revolutionary Socialism, by the French anarchist revolutionary syndicalists Charles Albert and Jean Duchène. Bordiga, already skeptical about the electoral system as the mechanism to seize power, explicitly agreed with their “criticism that parliamentary action would suffocate any other activity.” However, his 1913 position on collective consciousness is very different from what he will expose in 1922’s “The Democratic Principle.” In commenting on the 1913 elections Bordiga considered that:

It is […] undisputable that the conquests of Socialism, from the maximum to the immediate, must be a product of the large masses, which form a collective consciousness of their own interests and of their own future. The large masses must be convinced […] they should not abdicate their safety into the hands of a few executives. […] in the current conditions, any form of class action – not only the elections, but also syndicalist action and even street uprisings – present the risk that the masses will give up actual control of their own interests and entrust it to a given number of ‘leaders.’

However, the 1922 criticism of the majority principle (or majoritarian principle as Bordiga called it) seems to say otherwise. In 1922, Bordiga no longer believed that large masses must be convinced, nor that the majority is able to make the right decision, and he justifies centralism because he expects that when the Party is called to exercise power a hierarchy will emerge.

In June, 1914 the Kingdom of Italy was shaken by a week of strikes, demonstrations, and uprisings. On the one hand the pro-war elite understood that it would be hard to bring a country in such an agitated state into a geopolitical conflict; on the other hand, the revolutionary activists realized that a revolution was not yet possible in Italy. Bordiga blamed the failure of the unrest on Confederal Unions’ decision to call the national general strike off too early. He read the defeat of the 1920 occupations in the same way. In his article “Democracy and Socialism” in July, 1914, Bordiga clearly concluded that Socialism was the “solemn condemnation […] of the democratic formula, and of the deceits that this contains.” This article refers most probably to bourgeois democracy, but it contains the main elements of the 1922 critique of the democratic principle. In August 1914, Europe was at war, but Italy remained neutral until May, 1915. A solid pro war campaign, but most of all a secret agreement with the Entente, eventually brought Italy into war. Bordiga was a consistent and fervent antimilitarist before and during the war, and declared for the Bolsheviks as soon as they seized power in November 1917. Overall, the PSI was able to maintain a relatively cohesive antiwar position, although the reformists gave some concessions to the nation’s defense propaganda after the infamous Caporetto defeat. Regarding the October Revolution, they were more cautious and soon after many came to share Kautsky and Martov’s critical positions. This shows that the split of the revolutionary faction from the reformists was in the air long before the 21 points dictated by the Third International in the summer of 1920.

The first three post-war years in Italy were full of upheavals and dramatic occurrences. Despite its formal military victory, Italy had all the characteristics of a defeated country. Poverty, unemployment, and inflation created an explosive mix. 1919 was a year of unrest. There were major strikes, demonstrations, and land occupations. These were punctually sedated by brutal police actions. In the 1919 elections, the PSI became the leading Party by gaining a little more than 30% of the vote. Yet, the old liberal system, with the help of the newly formed Popular Party (Roman catholic oriented), managed to put together a weak coalition and pushed the socialist to the opposition. The “red scare” or, in other words, the “Bolshevik threat” was often used to justify disproportionate reactionary violence by the police forces against workers. The civil war atmosphere extended into 1920 when major factories were occupied by workers. It needs to be clarified that real conditions for a revolution in Italy did not exist. However, amongst the left only a few reformists seemed to be aware of it. Towards the end of 1920 the counterattack was disproportionately harsh and more and more in the hands of private militias. Militias formed in the rural areas of the Po valley by war veterans and active members of the police forces. Mussolini’s fascist movement, made up by what could be described as veteran’s unions in 1919, became, thanks to his journal Il Popolo d’Italia, the main voice of those militias, or action squads.

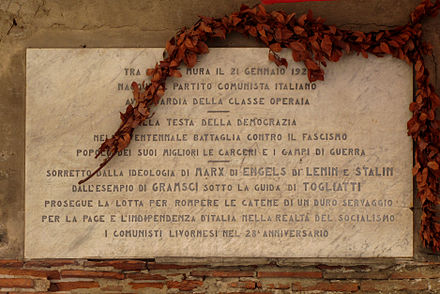

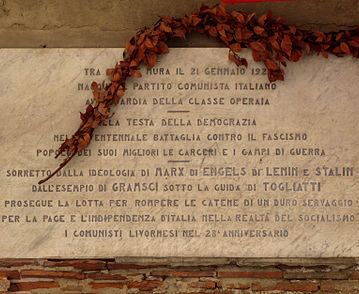

At the Bologna national Congress of 1919, the PSI formally adhered to the Third International. Just before that Congress, a Communist faction had formed around Bordiga, also known as the Abstentionists. Bordiga’s aversion to electoral partaking, i.e., the abstention, became a concrete Party tendency within the Intransigents. When Bordiga participated in the 2nd Congress of the Third International in the summer of 1920, his ideas about abstentionism were on full display, so much so that Lenin even dedicated a section of his Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder to his positions. However, Bordiga subordinated himself to Third International discipline as soon as they forced the reformists out of the Party. Indeed, Bordiga was the author of the 21st condition of admission into the Third International, which ensured that all Parties which would not conform to the other 20 conditions had to be expelled. By doing so Bordiga wanted to force the PSI to expel the reformists and change its name to the Communist Party. This did not happen and in January 1921 the Communists left the PSI, Bordiga becoming the de facto leader of the newly born Party.

While Bordiga and comrades were occupied with Party matters, agrarian fascism was rapidly growing. From the first important act of squadrismo (i.e., organized right-wing political violence), the so-called “D’Accursio raid” on the 21st of November 1920 in Bologna, until the May elections of 1921, a real civil war broke out, leading to the destruction of the major workers organizations and most socialist municipal administrations in the north of Italy. This was possible only thanks to Government connivance with the fascists, or in other words, full immunity for fascist crimes. The 1921 elections were heavily conditioned by the fascist squads’ violence and this, along with the national blocks with the liberals and the populars, allowed 45 fascists, Mussolini included, to enter Parliament.5 Bordiga did not neglect the fascist phenomenon. His analysis on the one hand did not make the common mistake to see the fascist rise as a consequence of the missed revolution. On the other hand, he minimized its originality, as he believed that fascism was no different from previous repressive legitimate Governments of Francesco Crispi and Luigi Pelloux.

At the 3rd Congress of the International in July 1921 Bordiga and the Russian Bolsheviks began their conflictual relationship over the bolshevization of the Italian Communist Party. In Germany, the March Action, sustained by the VKPD Zentrale and heavily pushed by the Third International, resulted in utter failure. Thus, now that Zinoviev rejected the “offensive” theory, in which Bordiga placed a certain amount of faith, and even worse, now that Zinoviev turned around into the promotion of the “united front” tactic, Bordiga vented his disagreement openly. The united front tactic meant that if the PSI expelled the reformists, they could join the Third International and create a coalition with the Italian Communist Party. For Bordiga this was unacceptable as he saw the PSI socialists as the worst kind of “fascists” in disguise. When the Socialist Party finally expelled the “Turatians” on the 24 of November 1922, the Russian Bolshevik Party addressed a formal letter signed by Lenin, Trotsky, Zinoviev, Radek, and Bukharin to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Italy in which it demanded the merger of the Communist Party of Italy and the PSI. In the end, this did not take place because the PSI eventually decided to separate from the Third International entirely.

By the end of 1921, after Mussolini’s failed attempt to normalize the fascist militias, a failure which almost costs him his leadership, the fascist movement formally organized into the “Partito Nazionale Fascista” (PNF, i.e., Fascist National Party). Thus, in February 1922 when “The Democratic Principle” was written, the PNF was already formed, 45 fascists were in Parliament, fascist violence continued, the dispute with the Third International was mounting, and Bordiga was about to publish the “Theses on Tactics,” also known as “Rome Theses.”

The Essay

“Il principio democratico” (i.e., “The Democratic Principle”) was published as a Bordiga-signed article in the 18th issue of Rassegna Comunista on the 28th of February 1922.6 In this text Bordiga explained that there is a theoretical and a practical contradiction between the bourgeois idea of democracy and the social class system. In his own words Bordiga writes that the Marxist critique shows a: “[…] theoretical inconsistency and the practical deception [“insidia” in Italian] of a system which would want to reconcile political equality with society’s division in social classes determined by the nature of the production system.” In other words, political equality and class inequality cannot coexist.

The key point in Bordiga’s argument was explained in the following sentence: “Political freedom and equality (as intended by the liberal theory) contained in the right of suffrage are nonsense if not on the basis of non-fundamental economic disparity.” That is to say, the liberal concept of political freedom and equality is unrealistic within capitalism because people are not socio-economically equal. For Bordiga, to think otherwise means giving the working class the illusion that they can vote on equal terms with their bourgeois class counterparts. In reality, the rules and the players’ behavior are dictated by the bourgeois class alone. Bordiga added, however, that the very right of suffrage is accepted within proletarian class organizations since these ought to have a democratic character.

Bordiga rejects the liberal idea that the human rights ideal (i.e., according to which we are all born equal and therefore we all share some basic rights),7 can coexist with the actual reality created by the capitalist division of labor, which, by definition, separates the rights of humans who possess the means of production and distribution from those who possess only their labor power. To give an overly simplified example, according to Bordiga’s point, in the current society, the vote of a nurse, or of a metalworker, will count less that a vote of a banker, or of a CEO, because the political institutions are influenced and constituted more by the latter two. Most importantly, Bordiga’s point goes beyond the not-so original criticism of universal suffrage,8 because he rejects the a priori absolute acceptance of the democratic principle even in class homogeneous organisms. In other words, even in workers’ organizations or in a society with no social classes nothing says that the democratic principle would be the best and most natural form of government.

Bordiga explained rather clearly that the deception social democracy has inherited from liberal doctrine, rests on the idea that «privileges» cease to exist as soon as an electoral majority is formed:9 “[…] it can appear a seductive logical construction only if we begin from the hypothesis that the vote or otherwise the judgment, the opinion, the conscience, of each voter has the same weight in conferring their proxies for the administration of the collective affairs.” For Bordiga this concept cannot be accepted by Marxist socialists because it is the furthest thing from the materialist doctrine since “it sets each individual as a perfect unit of a system composed by many units potentially equivalent among each other.”

Bordiga then began a brief history of social organization:

At the beginning we can imagine, without making big errors, the existence of a living form of humankind completely unorganized. […] The unit of the individual has biological sense [but] from a social standpoint not all units have the same value and the collectivity arises just from relations and from camps [“schieramenti” in Italian] in which the part and the activity of each one have no individual but a collective function because of the multiple influences of the social environment.

In other words, Bordiga claims that even in the most elementary forms of social organization the single individual, seen as the simplest social unit, did not make sense. It is rather the opposite, the simplest form of social unit is already collectivity organized on a unitarian basis, and it is, in simple words, the family. Bordiga argues that after the family other types of human organized collectivities emerged. And that those units can be compared “only in a way” to organic units, such as a biological cell. These elementary units, made of either single people or of groups of people, have diverse functions and they are in continuous exchange with one another. To explain the dynamics around such elementary units Bordiga takes once more the family example. He explains that those units change in a similar fashion as a family would : “The family element has a unitarian life which does not depend upon the number of the individuals that it contains, but upon the network of their relationships.” The evolution of those units goes from the families to dynasties, castes, armies, states, empires, corporations, parties. The increasing complexity of those units is due to the increasing complexity of relationships and social hierarchies due to the increasing division of labor. It boils down to organized collectivities who receive an external hierarchy or organized collectivities who give themselves an internal hierarchy.

In the case of the external hierarchy a simple example is the chief (e.g., king) appointed by God. With regard to the collectivities organized by an internal hierarchy the debate goes into the democratic principle. The primary problem is how to assign such a hierarchy. Bordiga considers two cases, on the one side, the entire society or more specifically a given nation, on the other side, smaller organizations such as a proletarian Party or Unions. For the entire society the democratic principle is to be rejected because it is based on the illusion of equality. To quote Bordiga: “Our criticism confutes the lie [“inganno” in Italian] that the democratic and parliamentary State mechanism, which emerged from the modern liberal constitutions, is an organization of all citizens in all citizens’ interest. […] the State remains despite the exterior outlook of people sovereignty the organ of the superior economic class and its tool of defense.”

Would, however, the democratic principle apply well to the proletarian institutions?

Bordiga’s answer is not straightforward. As long as the proletarian institution is the proletarian State, Bordiga answers that it does not really matter. His argument is that what matters is that the proletarian State must tear down the bourgeois economic privileges and political and military resistances that buffer them. If this can be achieved by mass consultation, so be it. If otherwise, and it takes the work of very restricted executive organisms endowed with full power, this is also fine. Only the circumstances will determine what form of representation mechanism will best adapt. If the proletarian institution is the syndicate (i.e., the union), which according to Bordiga can be part of the proletarian State, yes, the democratic principle makes sense. When the proletarian institution is the Party, unlike the syndicate, this does not have the same uniformity in economic identity and interests, but the Party works in space (from national to international) and time (past, present until the emancipation). Bordiga admits “undoubtedly so far there is no better way than to stick mostly with the majoritarian principle” but when the party is called to exercise executive power it is natural that a Party hierarchy would emerge (e.g., centralism). Thus, one more reason for the workers movement to free up from the bond of the democratic principle.

Bordiga concludes with the following:

The democratic criterion so far is for us a material accident for constructing our internal organization and forming our Party rules: it is not the indispensable platform. This is why we would not adopt as principle the known organization formula called «democratic centralism». Democracy cannot be for us a principle; centralism is undoubtedly so because the essential characters of the Party organization must be the structural and movement unit. To ensure space continuity of the Party structure the term centralism is sufficient, and to introduce the essential concept of time continuity, […] we would propose to say that the Communist Party found its organization on organic centralism.

If we can dare an interpretation of Bordiga’s organic centralism, he might have thought of something like a Marxist Executive Committee for each Nation coordinated by the Chief Executive Committee of the International Communist Association. Those Committees would, organically (i.e., naturally), renew their members in time based on the given circumstances (e.g., competencies, predispositions, skills, age, theoretical deviations, external threats).

Critique of Bordiga’s Concept of Democracy

Back in January 2022, Daniel Melo published an article in Cosmonaut titled “Why Bordiga Got Democracy Wrong.”10 It is a well written, although incomplete, summary of Bordiga’s “The Democratic Principle.” According to Daniel Melo there are at least two drawbacks in Bordiga’s argumentation.

On the one hand, he limits his critique of democracy solely to its puny implementation in bourgeoise politics, throwing out the democratic baby with the bourgeoise bathwater. What’s more, his argument leaps from the failures of bourgeoise democracy to conclude that there is no value in majority decision-making itself. On the other hand, his vision of centralism rises to this same level of idealized and unexamined principle that he condemns, with precious little argument from Bordiga.

Melo continues:

Bordiga’s focus on these ends with a quick endorsement of centralism’s means is a dangerous one. To neglect the means of organization in a revolutionary moment to instead solely focus on ends, invites a kind of brutal utilitarianism that can (and arguably, has) cost millions of the very lives it is supposedly seeking to emancipate.

Finally, Melo exposes: “Bordiga’s analysis [when it] stumbles headlong into a rather fatal error by conflating electoral politics as the heart and soul of democracy.”

This article elicited a letter response from Parker M. Shea.11 Shea argues that Melo is not really specific in explaining what democracy means. According to Shea, Melo: “[…] appears to be falling precisely into the trap that Bordiga warns us about” when “suggesting that capitalists be ‘pulled into the democratic framework’.” Namely, how could Melo ensure political equality between the different social classes? Furthermore, Shea asks: “that is the question of whether democracy ought to be a democracy of demands or a democracy of actions.”

Daniel Melo’s response to Shea in “Bordiga and Democracy Redux” is rather complex and a little rushed, necessitating a close read.12 If we understand it well, Melo draws attention to the purpose of democracy. Is it for demands or for action? As Melo puts it: “what demands or actions do we take, and to what ends?”, “This in part implicates the state and its role in a democratic overthrow of capitalism and the development of socialism.” … “the radical vision of democracy requires an ability for the collective to throw its arms around the full spectrum of social relationships, both political and economic.”

In 1913, Bordiga believed that the masses should not delegate the action to a few leaders because he distrusted electoral action as a mechanism of delegation of power to the working class. In 1922, given several major failures to seize power by social democratic means, including the unfruitful 1919 PSI electoral victory, the Hungarian case, and above all the counterrevolutionary role of the SPD during the 1918-1920 German Revolution, Bordiga no longer trusted the “large” masses, intended here more as the majority, but rather paradoxically a decisive Marxist centralized minority to bring about social change. The influence of Lenin and Trotsky in Bordiga’s way of thinking cannot be overlooked. If we interpret Bordiga’s thought correctly, leaders do not need to be, or even should not be appointed by the majority, but rather emerge as a natural revolutionary unit, natural leaders of the working class. Would this unit be the Soviet? Would it be the Executive Committee? Probably these details did not interest Bordiga. Why doesn’t Bordiga trust the democratic principle to provide a mandate to their elite? In Bordiga’s eyes democracy fails on three levels. Its bourgeois electoral form dissipates revolutionary potential energy, its liberal equalitarian lie disenfranchises the masses, and even if the socialist Party was elected to power bourgeois democracy’s formal constraints would act as a reactionary brake.

We could try to grab the lifeline Bordiga throws to us when he maintains the democratic principle in a class uniform context, for instance, in the case of trade unions. Could Melo’s radical democracy be just that? Obviously not. Is it enough to say that Bordiga’s idea of democracy, that is electoral politics, and radical democracy, whatever it may be, are different? Would this be enough to overcome Bordiga’s very skepticism towards using the electoral machine? If it is true that radical democracy does not have anything to do with electoral politics, then is it party democracy? Is it alternative democracy?

Melo claims that “radical democracy examines and decides all rights, including the right to certain legal and political protections (like property) as requiring mutually justifiable reasons for their maintenance; something that electoral politics will not and cannot deliver.”

How would the working class dispossess the owner of the means of production via radical democracy? We understand that Bordiga’s problem with the democratic principle was not limited to electoral politics. For Bordiga social relations are a kind of natural process and the working class must figure out its own way, organic centralism. For Bordiga even radical democracy would not work because of the heterogeneity of the working class. It would be like forcing the equality lie into a one class system instead of a multiclass system. Being one class does not mean being socially homogeneous. This is actually a fair point from old leftism.

It may not seem so, but we deeply disagree with Bordiga’s rejection of the democratic principle, despite his fair skepticism of the possibility of winning the game by playing according to someone else’s rules. This skepticism or disgust for the electoral mechanism is not even a prerogative of the extreme left. The subversive right can and did use a very similar argument to dismiss any form of democracy. We disagree with Bordiga when he comes back to his 1913 statement: “The large masses must be convinced […] they should not abdicate their safety into the hands of a few executives.”

This is the crucial Blanquist and, in a certain way, Leninist mistake. What we miss in all this is that the social collectivity must organize and administer itself. To do so the social collectivity must take control of the means of production and their product. To avoid that this become a vicious cycle (i.e. waiting for the moment that the social collectivity is able to take control of the means of production to administer itself), the social collectivity must organize itself into a Party as intended and described in the “Resolution of the London Conference on Working Class Political Action, as adopted by the London Conference of the International September 1871,” where it reads:

[…]. Considering, that against this collective power of the propertied classes the working class cannot act, as a class, except by constituting itself into a political party, distinct from, and opposed to, all old parties formed by the propertied classes. That this constitution of the working class into a political party is indispensable in order to ensure the triumph of the social revolution and its ultimate end- abolition of classes […]13

The social collectivity organized in a political party is an indispensable precondition to take control of the means of production. If we analyze what this means in practice, it does not mean an elite minority (which knows what is best for the working class) will organize in a Party, but the class will organize in a Party, an International Party. But it is a political party, where political means that all members, with no leaders, take actively part in its organization and administration as they would need to be able to do for the entire social collectivity in a socialist society. Anyone who argues this is impossible argues socialism is impossible. In practice what would this entail? It would mean that part of the day will need to be invested in political activity, meaning the organization and administration of the class Party. Would this organization and administration leave space to an enlightened Executive Committee. No! Organization would need to follow a democratic principle. In order to succeed the Party must have no leaders. Why do we say that? We say this because we strongly believe that humans should organize their “own powers” as social powers!

Marx did analyze the concepts of égalité and liberté arising from the Great Revolution. He sharply noted, what Bordiga would call “the lie” around equality, that: “Equality, used here in its non-political sense, is nothing but the equality of the liberté” and what is this freedom?

[…] the right to enjoy one’s property and to dispose of it at one’s discretion (à son gré), without regard to other men, independently of society, the right of self-interest. This individual liberty and its application form the basis of civil society. It makes every man see in other men not the realization of his own freedom, but the barrier to it. But, above all, it proclaims the right of man.

The concept of security does not raise civil society above its egoism. On the contrary, security is the insurance of egoism.

Marx and Bordiga are right in criticizing the hypocrisy of the bourgeoisie in giving absolute value to their idea of equality and freedom, which otherwise enforces and recognizes the “real man only in the shape of the egoistic individual.” Marx cites Rousseau to explain what a political man should be:

[…] He has to take from man his own powers, and give him in exchange alien powers which he cannot employ without the help of other men.” closes Marx “Only when the real, individual man re-absorbs in himself the abstract citizen, and as an individual human being has become a species-being in his everyday life, in his particular work, and in his particular situation, only when man has recognized and organized his “own powers” as social powers, and, consequently, no longer separates social power from himself in the shape of political power, only then will human emancipation have been accomplished.

The young Marx still maintains a moralistic outlook, but in essence the organization of the workers “own powers” as social powers is the key transformation needed to create a worker’s political party and a new society. However, this revelation says that the power of one individual works only in a collective context, this does not say explicitly that the Class-Party should organize itself according to a democratic principle, but it does say it has to be organized by the whole, which is in other words very close to the definition of demos-kratía. In a letter exchange between Marx and Engles in 1851 an interesting aspect emerges. While Marx is amused by Proudhon’s “cheeky outpourings” about Louis Blanc, Rousseau, and Robespierre; Engels, far less amused, points out:

There are one or two nice things in the attacks on L. Blanc, Robespierre, and Rousseau, but on the whole it would be hard to find anything more pretentiously insipid than his critique of politics, e.g. in the case of democracy, in which, like the “Neue Preussische Zeitung” and all the old historical school, he comes up with head-counting, and in which, without a blush, he builds up systems out of small, practical deliberations worthy of a schoolboy. And what a great idea that “pouvoir” [power] and “liberté” are irreconcilably opposed, and that no form of government can provide him with sufficient moral grounds why he should obey it! “Par Dieu!” [By God!] Then what does one need “pouvoir” for?

In a way Proudhon’s argument against equality is a version of Bordiga’s critique of the democratic principle from seventy years earlier. Proudhon was annoyed by the time wasted following Rousseau which had formed the “culte des anciens révolutionnaires,” because the Social Contract as thought by Rousseau was an illusion, hence a waste of time. Proudhon argues that the new form of Government is not universally equal. Like Bordiga, Proudhon argues that this “social contract” would become a fraud, because it would safeguard the interests of the owners at the expense of the have-nots. Thus, the poor would not have the same representation rights as the rich. Proudhon continues, and here it seems Bordiga could have written it, that Rousseau’s rhetorical work distracted from the bases of negation of the Government.14 Yet, Proudhon’s solution is a reformed capitalism in favor of a petite bourgeoisie, where the equality principle becomes repartition exercised, instead of by taxation, through dividends. Although Marx enjoyed the attack on the contradiction in Rousseau’s Social Contract made by Proudhon, he did agree with Engels in considering Proudhon a “scientific” charlatan.

In 1892, in a reply to the freemason republican philosopher Giovanni Bovio, Engels pointed out that although he believed that “odds are ten to one that our rulers […] will use violence against us” before the socialist party will become the majority and proceed to take power. Yet to answer Bovio’s naïve question: “what power? Will it be monarchic, or republican, or will it go back to Weitling’s utopia, superseded by the Communist Manifesto of January 1848?”, Engles spelled out: “Marx and I, for forty years, repeated ad nauseam that for us the democratic republic is the only political form in which the struggle between the working class and the capitalist class can first universalized and then culminate in the decisive victory of the proletariat.”15 Engles, as well as Marx, believed that universal suffrage could be “the weapon, which, in the hands of class-conscious workers, has a longer range and a surer aim than a small caliber magazine rifle in the hands of a trained soldier!”16

And this is also our final point. Bordiga’s 1922 critique of the democratic principle has deep roots. Some are justified by the fact that “the executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.” It is also clear that the ruling class will change the rules if they see that their common affairs are put in danger by their method of representation. The only democracy that can work for the working class and in a socialist society is the one where the collectivity actively participates. Going back to Melo’s pie analogy we agree that the only democratic principle we as Marxist socialists can accept is the one where we all can choose how to make the pie, who gets to make the pie and how to slice the pie. The first point is probably the one that has been neglected. The action of delegating, which in the analogy is who gets to make that choice, would still miss the real essence of a fully democratic principle.

From the Oxford dictionary the verb ‘delegate’ means “to give part of your work, power, or authority to someone in a lower position than you” and the verb ‘represent’ means “to act or speak officially for somebody and defend their interests.” Thus, one delegate voted by the majority of a larger group of people is given the power, or authority to act or speak to defend their interests. This covers who gets to make that choice. Yet, this is an incomplete and thus faulty approach. The majority needs to be able to be the ‘delegate’ itself. The “power or authority” stays with the majority who actively decides on the specific organization and administration content (e.g., how to make the pie), if the majority must be represented a representative will be nominated democratically. Bordiga saw this as the institution of “chatterboxes who discuss interminably without ever acting.” If the working class cannot find an effective way to decide and act and needs to “entrust [its power] to a given number of ‘leaders’,” then the working class is not mature enough to establish socialism.

- https://www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/socialist-standard/2017/2010s/no-1349-january-2017/amadeo-bordiga-intransigent-socialist/; https://www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/socialist-standard/2017/2010s/no-1350-february-2017/early-bordiga-and-electoral-activity/; https://www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/socialist-standard/2017/2010s/no-1351-march-2017/bordiga-and-first-world-war/; https://socialismo-mondiale.blogspot.com/2016/08/il-giovane-bordiga-parte-prima.html?m=0.

- Anna Kuliscioff began her radical career in the terrorist organization, Južnye buntary, eventually abandoning itin favor of Marxism around 1879. She was also Andrea Costa’s partner, with whom she had a daughter, Andreina. When her relationship with Costa ended, she became close with Turati. They would become an inseparable couple of Italian socialism.

- The participation of a Socialist member in a bourgeois Government.

- Integralisti does translate in Integralists but it did not have anything to do with Catholic integralism, church authority, or political power. In this case Integralist was derived from the adjective integral as in “formed of constituent parts; united,” and indicated that this faction wanted to unite the reformists with the intransigents.

- Despite the physical violence committed by the fascists against socialists and communists, the Left still won 122 and 16 seats respectively during the 1921 election. For a detailed account of how the fascists rose to power we have published (unfortunately for the moment only in Italian) a number of articles to be found on https://adattamentosocialista.blogspot.com/.

- Bordiga had developed with time a rather strict publication policy. According to which political writings should not be linked to a person, but rather to the movement. That is why it is rather significant to observe that this was a signed article. Bordiga also published articles in Rassegna Comunista in May 1921. These articles dealt with the Italian question about the Livorno split. He published again in November 1921 on the same matter, and again in July of the same year Rassegna Comunista was chosen to publish the speech he gave on 28 of December 1921 at the first national Congress of the French Communist Party in Marseille. These three articles are all signed as well.

- Bordiga here shows a lack of juridical knowledge. Natural law is not a liberal discovery, it has a much older tradition, Thomas Aquinas for the Christians, Aristotle Stoic for the Greco-Roman tradition.

- For instance, in Marx’s Considerings, a preamble of 1880 Programme of the ‘Parti Ouvrier Socialiste Français,’ it is pointed out “that a such an organization must be pursued by all the means the proletariat has at its disposal including universal suffrage which will thus be transformed from the instrument of deception that it has been until now into an instrument of emancipation.”

- It is otherwise the case that social democracy was not so naïve to believe that as soon as an electoral majority was reached this would have been the end for the capitalist system along with its injustices and privileges. It is a bias, or in other words tendential, generalization that Bordiga uses to make a point.

- https://cosmonautmag.com/2022/01/why-bordiga-got-democracy-wrong/.

- https://cosmonautmag.com/2022/01/letters-bordiga-and-the-bathwater/.

- https://cosmonautmag.com/2022/02/letter-bordiga-and-democracy-redux/.

- https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1871/09/politics-resolution.htm.

- Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Idée générale de la révolution au XIXe siècle, choix d’études sur la pratique révolutionnaire et industrielle. 1851. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6115074k.texteImage.

- Reply to the Honorable Giovanni Bovio, p. 270 https://www.hekmatist.com/Marx%20Engles/Marx%20&%20Engels%20Collected%20Works%20Volume%2027_%20Ka%20-%20Karl%20Marx.pdf.

- To the fourth Austrian Party Congress, p. 442 https://www.hekmatist.com/Marx%20Engles/Marx%20&%20Engels%20Collected%20Works%20Volume%2027_%20Ka%20-%20Karl%20Marx.pdf.