Sudip Bhattacharya looks to the Reagan era to understand the rise of the current US right, drawing from interviews with various US historians.

Despite the Biden administration’s sudden lack of interest in uncovering more about the insurrection on January 6th and their willingness to work with the GOP, a party now dominated by white nationalists and nihilists, the right has proven to be a powerful force in U.S. politics. This is seen in their stall basic political procedures in bourgeois society such as the counting of votes, as well as their capacity to generate a rabid support base openly calling for a coup. It is incumbent upon socialists and the broader Left to grapple with the ascendency of the right-wing, or else risk developing political strategies that fail to counter the right wing’s march toward developing an even more repressive political landscape.

To accomplish this task of gathering useful insights about the current right-wing threat, we must compare it to previous eras that are similar to our own, such as the late 1970s, which witnessed the rise of the New Right and Reaganism. In fact, the rise of the New Right and Reaganism was also during a time of political and economic turmoil across the country with racism and white identity politics being mobilized by particular figures. As Douglas Rossinow, Professor of History and interim Dean of the College of Liberal Arts at Metropolitan State University, shared with me,

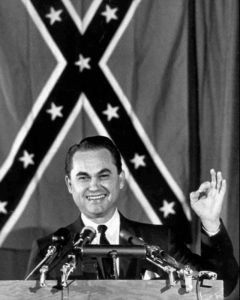

Reagan capitalized on [white backlash] more and rode it farther than either Wallace or Nixon. He doesn’t seem as crude as Trump but in the context of the times, Reagan’s long record of hostility toward the civil rights movement and its achievements culminated in his emergence in 1980 as the leader of a conservative pushback against various elements of the civil rights agenda, including affirmative action.

By juxtaposing the late 1970s to our own time period, we learn that the rise of the right-wing is not miraculous but rather, precipitated by crisis in the economy and the weakness of forces who could’ve held such anti-democratic and racist forces in check. If there is one major insight to take away, it is one that’s been reinforced by Marxist scholars for generations, such as Antonio Gramsci and Clara Zetkin, which is that political crisis does not promise socialist or progressive change.

I will expand upon the contrasts between the late 1970s and our time through theory, history and by incorporating insights from original interviews I conducted with experts on the right, such as Douglas Rossinow, Daniel Lucks, Brendan O’Connor, and Joe Lowndes.

CRISIS & CONTRADICTION

The era in which the New Right and Reaganism flourished was also an era of economic unrest and political realignment. By the time of Reagan’s 1980 Presidential run, (his third attempt at the throne), the country was staggering through its deepest recession in recent memory. Companies, eyeing other sources of “investment,” shed employees. Wages stagnated. Inflation was suddenly on the minds of many, elite and non-elite alike. In conversation, Rossinow, the author of The Reagan Era: A History of the 1980s, explained that

The single most important issue was inflation. That might seem mundane. But it was more significant than it has been for a long time now. It was a serious object of public concern. Opinion polls showed higher public concerns with inflation than with unemployment.

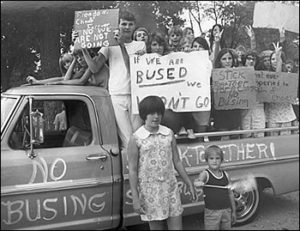

For decades, the New Deal had lifted many Americans out of poverty and provided some semblance of the “American Dream” to some. Yet by the late 1960s, the New Deal coalition was starting to fall apart due to its own internal contradictions and due to the limits of reformist politics. When the New Deal took shape, for instance, many of its policies did not challenge the regressive politics of Jim Crow or other explicitly oppressive regimes throughout the country, such as the treatment of farmworkers on the West Coast. Instead, Southern Democrats, who were part of the New Deal coalition, were given the power to distribute resources how they saw fit, and shaping national policy on labor, which meant excluding protections and rights for agricultural workers and domestic labor, two occupations that included a large swath of Black and brown people across the South and Southwest. Furthermore, tackling white supremacy and white identity politics among segments of white working people beyond the Deep South was avoided by New Deal Democrats and by mainstream labor unions. Hence, when Black and other non-white groups would eventually seek to challenge such oppressive conditions and policies, including in places like Chicago, they were met with violence and intimidation by white workers. Such clashes or rather, vitriol let loose by white mobs, would often still go unchallenged by Democrat Party members and by mainstream labor unions. This contributed to the same white workers, those who had been considered “ethnic” whites, to become vulnerable to the tactics and rhetoric of right-wing populists, such as George Wallace, the segregationist who garnered support for his presidential campaign in places up north like in mainly Italian and Irish American neighborhoods in Philadelphia.

Another pressing issue was the fact that mainstream labor unions believed in the idea that they could achieve what their constituents needed by being part of the Democrat Party coalition that emerged after WWII. This meant organizing workers but doing so without the idea of class struggle or class conflict. Seeking reforms under capitalism was seen as possible in an ideology of corporatist class cooperation. This led to mainstream labor unions, as represented within the AFL-CIO umbrella, to abide by Democrat Party prerogatives above all else, which entailed purging Left-wing radicals when asked to by Democrat Party leaders. It also meant seeking negotiations with major companies, such as the “deal” struck between auto workers and the leading car manufacturers, in which the UAW agreed to no longer use strikes as a means of getting what they needed and instead, to rely on contract negotiations instead.

Overall, such maneuvers between labor and the Democrat Party advantaged the more “moderate” elements of the labor movement, those who believed in civil rights and were still pro-worker, and yet, were willing to push for such issues without necessarily challenging the Democrat Party leadership or the redbaiting that was starting to take place. Furthermore, they were not supportive of more radical elements confronting capitalism and imperialism, such as Black revolutionaries like the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement and the Black Panther Party. he historian Mike Davis writes in his Prisoners of the American Dream,

In the absence of unity with the Black movement and revitalization of rank-and-file participation, the trade unions became the captive political base for an anti-communist ‘liberal’ wing of the Democratic Party, whose capacity to enact substantive reform was permanently constrained by both the weight of the Democratic right-wing and the exigencies of Cold War bipartisanship.

With this misguided belief that workers could gain what they need by serving the Democrat Party or by working within capital, labor unions became complacent. They ceased to organize against the capitalists (which is what Left-wing organizers pushed for), whose most extreme elements, such as Koch Industries, continued to sustain think tanks and grassroots organizations that tapped into segments of the middle class who believed themselves to be the “deserving” few against the “undeserving” hordes of “welfare cheats” and “lazy” labor union workers out to get them. When the next capitalist crisis did occur, as one would expect, by the 1970s, labor unions were unprepared to exploit the crisis while the capitalist classes were able to exploit it, stitching together coalitions between themselves and segments of the disaffected masses against labor unions and other vestiges of the “excesses” of the 1960s, even extending to civil rights activists.

As the economy shifted and as leading capitalists hungered for more, workers in what would be known as the service-sector industry grew, as well as the number of people working in “white-collar” occupations, as engineers and lawyers, and in cubicles in general. Overall, such workers, especially those who are “white collar” were disconnected from the labor movement relative to industrial workers. Nelson Lichtenstein explains in State of the Union,

Indeed, failure of the trade unions to organize white collar and professional workers, which was becoming well noted as the 1950s turned into the 1960s, seemed to confirm that these workers had an interest and outlook inherently hostile to the union idea.

Thus, when labor unions did strike in the late 1970s, they were doing so without significant support from a large percentage of the new workforce. As a result this new workforce was much more open to right-wing political appeals.

The Left as well had been drastically weakened by the late 1970s, just as the New Right was gathering momentum. Prior to the 1950s, the Left, as exemplified by elements within the CIO and of course, among communists, had been building a mass constituency for themselves. However, as the New Deal coalition was being forged, communist leadership in the U.S. and other Left-wing radicals were convinced that they could finally gain more influence in domestic politics by working alongside New Deal liberals. As detailed by Robin D.G. Kelley in his classic text, Hammer and Hoe, this tactic proved shortsighted, especially once the war was over and liberals within the Democrat Party and “moderates” in the labor movement moved against the Left, leading to purges and repression.

The same would happen during the civil rights movement, as Left-wing radicals like Jack O’Dell were driven out of the movement while others were assassinated or intimidated into silence. In turn, a “moderate” cadre within the civil rights movement would emerge, advocating for more people of color to serve in positions of power instead of systemic change to how our political institutions function. Hence, just as Black and non-white officials took power, the majority of non-white peoples were still left to fend for themselves, lacking policies that spoke to their material interests.

There was also a tendency among the Left, such as the New Communst Movement, especially by the late 1960s and early 1970s, to focus on organizing mainly through “unrest” or to romanticize “decentralized” models of political organizing that often led to more chaos and a lack of strategic direction. In the meantime, the capitalists and the right-wing were putting together coalitions that could influence politics nationally. Max Elbaum comments on this weakness in his Revolution in the Air:

The lack of a class anchor also contributed to the revolutionary left taking shape as a number of mutually hostile trends rather than a more cooperative alignment. Without minimizing the ideological and sociological differences between New Communist party builders, CPUSA supporters, revolutionary nationalists and others, the way their disagreements manifested themselves in bitter sectarian battles was at least partly framed by this problem. A more cohesive class base for the left, which in various ways would have held all radical forces accountable for advancing its interests, might have changed the equation, offering immediate negative consequences for unchecked intraleft conflict.

This lack of coordination and discipline and not doing the difficult and arduous work necessary to develop a mass constituency allowed for these groups on the Left to fracture and become infiltrated by class enemies and law enforcement.

Hence, even when Jimmy Carter was elected after Nixon, the Left and labor were no longer capable of exciting a base of support that could challenge the emergent right-wing. With the economy struggling, masses of people were left to fend for themselves, especially non-white people and a large number of workers overall, who felt no one was speaking for their interests in the political arena.

I spoke with Daniel Lucks, historian and lawyer and author of Reconsidering Reagan: Racism, Republicans and the Road to Trump, who explained,

“Things were really bad in the 70s. There was stagflation. Interest rates were sky-high. Unemployment was high. That freaked a lot of people out. There was a sense that Carter was incompetent. He was a good person but he couldn’t do his job.”

As mentioned earlier, the right were now the ones able and willing to mobilize for their own interests in the midst of an economic/political crisis.

“There were many activists within the business community and spokesmen for wealthy interests,” Rossinow explained, “They’d been building arguments for a host of economic policies, including deregulation, curbing the power of organized labor and providing large income tax cuts to the wealthy to spur investment. This was the supply side argument.”

Essentially, the rise of the right was not an issue of mass defection among liberals or among left-leaning people. Rather, the success of the right was their own success in mobilizing constituencies that were open to their appeals while oppressed and exploited peoples began caring less about traditional politics. Indeed, this has been the case during our own era as well, with traditional Democrat voters, such as African-Americans in the midwest choosing to not vote at all in the 2016 election, as explored by Malaika Jabaili in Current Affairs. Rossinow stated,

Reagan’s coalition, much like Trump’s coalition, was a traditional Republican coalition of people who skewed wealthier. However, augmenting that usual Republican coalition, both Reagan and Trump attracted a segment of the working class and less wealthy white voters.

This is an important point to remember as we head into the first few months of a Biden administration that has already failed in supporting policies that would excite most working people, such as supporting the minimum wage or being more vocal about pro-labor union policies like PRO Act, while labor unions and progressive groups lack influence across the country.

NEW BOSS > OLD BOSS

Brendan O’Connor, author of Blood Red Lines: How Nativism Fuels the Right, has been exploring the rise of the right in the modern era, pulling together threads of much longer trends in U.S. history, such as its settler-colonial history, with more recent ones, including the rise of a violent anti-immigrant politics against non-Europeans, especially Latinos:

“There are new aspects and dynamics; that is not a departure or is not as though we’ve entered a different dimension,” he explained. “It’s building on existing historical trends and dynamics that have been with us before the founding of the United States.”

Although “racial resentment” has been a constant in American right-wing discourse, its chief target does shift. When the “Western frontier” was “opened up” to “settlers”, it was the Chinese laborer who was public enemy number one. Then, during the late 1910s, with the second rise of the Ku Klux Klan, it was not only Black Americans but also, Jewish people and Southern and Eastern Europeans. Now, as O’Connor and others have recognized, some of the main targets of rage have become mainly “immigrants” and those perceived as immigrants—Latinos, especially.

This wielding of immigration as a hammer, ranging from the rhetoric surrounding the necessity of a giant wall on our southern border to the right for border agents to “punish” those crossing over by separating families (as Adam Serwer astutely noted, “cruelty is the point”), has served to inspire the base on the right, while drawing new people into the fold. After all, some on the American right have positioned themselves as protecting all workers, including Black and brown Americans, against the so-called scourge of “foreigners”. As O’Connor said to me,

Part of the fascistic elements of the Trump administration was turning immigration enforcement into a public spectacle that his base, and the rabid far right constituencies of the Republican party, could feel themselves participating in.

Essentially, Trump is part of the GOP tradition (and a general tradition in U.S. politics) to scapegoat the oppressed, especially conceptualized as non-white, but is also a point on the trajectory ushering in an extreme version of right-wing demagoguery and bloodlust. There is a pattern of GOP politics becoming a part of governing, which leads to some of its most extreme desires being curtailed and subsequently causing its social movements to become even more radical. Joseph Lowndes, professor of political science at the University of Oregon and co-author of Producers, Parasites, Patriots, a deep-dive into the right-wing, explained,

The way I see it broadly is that the trajectory of the American right from the late 1960s to the present would be something that is both cyclical and developmental. By cyclical, there have been moments of populist insurgency on the Right that get incorporated into Republican governance and as that Republican governance compromises as it must do, it opens up new opportunities for new populist insurgencies.

Hence, as Reagan focused on anti-Black politics but generally pushed against particular anti-immigrant rhetoric, figures like Pat Buchanan would lead right-wing social movements who felt betrayed that legal and “illegal” immigration was no longer on the agenda. Furthermore, the GOP, even if its leaders weren’t necessarily connected to the grassroots or sincere, have cultivated a right-wing base that is more willing to support figures and policymakers who don’t even bother paying lip-service to concepts like democracy, convinced they are caught in a “civilizational” struggle against the “undeserving”, which include Black and brown people who assert their own interests and so-called “socialists” and “cultural Marxists”. To this day, shows hosted by disgusting figures like Tucker Carlson, who traffic in white nationalist rhetoric, are incredibly popular, while politicians like Trump and Mike Lee, Republican senators from Utah, who espouse anti-democratic views, are heralded by the majority of Republican voters.

Thus, the general demographic trends haven’t necessarily changed among the right-wing but the intensity of their politics has increased. The belief in a civilizational struggle, with members of the right-wing viewing themselves as the grand stewards of U.S. power and influence, has led many among them to accept the idea that their “way of life” cannot be defended through bourgeois institutions. A significant number, around 20-25 percent of Republicans, supported the January 6th insurrection with nearly half believing it was a Left-wing conspiracy against Trump.

Again, the base of support that Reagan and Bush Sr. started to cultivate decades ago is the same base of people who support right-wing figures like Trump. These are mostly white small business owners, a certain segment of white working people, including those in the middle class, who have been divorced from union politics. Yet, since these same forces that have been marinating in white identity politics for the past few decades, and in pro-U.S. exceptionalist rhetoric with them as its “heroes” and vanguard as “taxpayers”, as “homeowners”, they have increasingly become more radicalized. Also, due to the fact that many of them have been steeped in the paranoid logic that as demographics change, whites and those committed to the “American Dream” myth (including Hispanic and Asian Americans who are anti-communist) will be one day surrounded by the “undeserving”, they have been convinced by right-wing thought leaders that they must do whatever it takes to stop this from happening, including preventing bourgeois-democratic procedures, like voting, from occurring by supporting voter-restriction efforts. As Rossinow explained,

The difference between the 1980s and in recent times is the changing demographics of the country. The white vote isn’t as big as it once was in the 1980s. In 1984, Reagan won a huge election, period. In 1984, 86 percent of those who voted were non-Hispanic whites. Reagan won two-thirds of the white vote. That was about fifty percent of the whole electorate. In 2016, the figure was seventy-four percent being white American. Winning the white vote, even by a lot, is not going to give a presidential candidate the landslide it gave Reagan in 1980 and 1984.

This is critical to keep in mind as we develop strategies to win against the right-wing. This should lead us to understand that as we organize for power, we cannot simply pretend as if the right has been the same as it always has been, or that we can only target the Democrat party in our efforts for power.“You got one side in insurgent mode,” Lowndes expressed to me, in reference to the GOP and the resurgent right-wing.

Having a group of people convinced they’re in a civilizational struggle means we have a multitude willing to hurt and harm others, especially oppressed people, from trans people to people of color generally, in order to maintain what they feel are their interests. To defeat this will require confrontation, not avoidance. It requires labor and the Left broadly to continue showing up at counter-protests against the right-wing but also, to develop self-defense groups and to find ways to organize those who would be the targets of the right-wing so they can actually feel safe.

THE FINAL AND FIRST DAYS

It should be evident, based on what we’ve reviewed so far, that moving forward, the Left and what remains of the labor movement must organize to confront capital and the right-wing without relying on the Democrat Party, which has simply shifted rightward as well. At every turn, the Democrat Party has been complicit in the rise of the right-wing, whether it’s been through the purge of left-wing radicals or by supporting policies that are also neoliberal to appease conservatives, including workers steeped in white identity politics. After all, just as Reagan was rising to prominence, the Democrat Party also saw candidates like Biden, who became an elected leader by voicing his opposition to desegregation efforts in Delaware.

Labor unions, therefore, must find ways to develop a mass constituency who will be ready and able to confront the businesses, the right-wing elements, the neoliberals across partisan lines. This has already started to happen in cities like Chicago, where the teachers’ union there has led campaigns for wages while also connecting their fight for better workplace conditions to better living conditions for all. For instance, the teachers’ union has viewed themselves as the vehicle to contend against institutions like ICE, who are rightfully seen as a vanguard of the right-wing. Consequently, the efforts of the teachers’ unions were successful since they were able to expand their base of support in the community, and the community, in turn, benefited due to the fact that it had more leverage over the existing political institutions through the teachers. There has also been evidence of linkages forming between working-class communities and labor during last summer’s unrest when thousands of workers led a one-day strike in support of BLM. Such actions are more necessary than ever for labor to grow stronger and for broader communities to actually have the means to win what they need.

The next critical element in beating back the right-wing has to do with the Left once more invested in forms of institutional organizing. Some of this is already taking place, as exemplified by the DSA’s recent campaign to fight for the PRO Act, which would make it much easier for workers to organize unions, even in places like the south and southwest. As mentioned earlier, the Left by the late 1960s had started to fetishize such things as decentralization, and began to develop a politics that was increasingly insular. Various strategies were taken by various groups, none of which sought to build power long-term. As Lichentstein explains, even the concept of the “union” was jettisoned completely by some.

“[…] New Left radicals began a furious search for an effective substitute [to the working class and its institutions],” he writes in State of the Union, adding, “Among the candidates were an interracial movement of the poor, which had emerged from the civil rights experience, a harder-edged black nationalism that some linked to an ascendant Third World revolutionism, and finally the idea of a ‘new working class’ of radicalized technocrats, engineers, and knowledge workers. The ideological half-life for these substitute proletariats proved remarkably short, even as they cast a long shadow forward over the political and academic landscape.”

The right-wing and the capitalists, at least those who know best, know that to win one must create organizations that can survive long-term. For the rightwing and the capitalists, this meant forming groups like ALEC, that have been an institutional force in helping coordinate their efforts across the country. For the Left, it should mean shifting away from local actions to developing institutions, such as unions among working people and other types of organizations that working people could rely on to achieve their interests longer-term. Without unions, the Left has no means of shaping the political landscape.

More importantly, it means also building organizations at the national level that can help fund efforts locally and bring groups together to strategize effectively rather than have various groups do whatever they feel is best. Imagine labor unions and Leftist organizations finally sharing some level of communication and forging some common vision for the fight ahead.

Finally, Left-wing organizations and the labor movement have to continue organizing explicitly against the right-wing. As mentioned, the right-wing are bent on doing whatever it takes to sustain power. Therefore, we must organize against whatever the right-wing have put forward, including voter-restriction laws, as well as the campaign against Critical Race Theory, and its mobilization against oppressed groups through anti-trans politics as well as against immigrants of color. Defeating the right-wing will require confrontations, like the one recently in Philadelphia, in which a crowd of people chased away the alt-right.

In the end, our efforts must be dynamic and not repeat mistakes of the past. Unless the right is crushed, they will persist to terrorize and degrade any attempts in providing even the most basic policy prescriptions and resources for most people, such as universal healthcare.