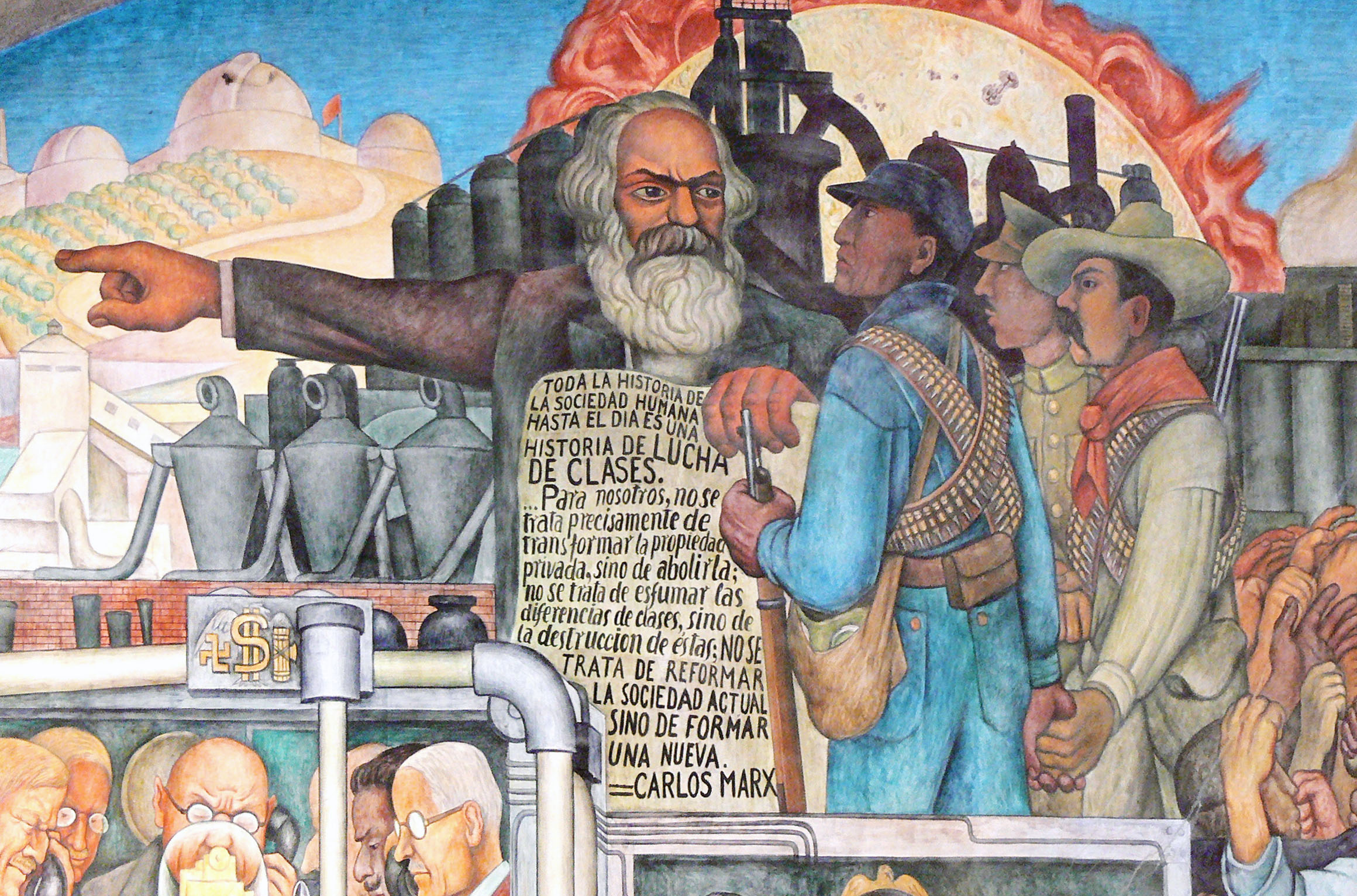

Steve Bloom considers what is living and what is dead in the corpus of Marxism with the intention of forging an adequate revolutionary theory for modern times.

I. Refounding Marxism

Back in the 1980s a current rose to prominence based on the idea that there was a need for “Rethinking Marxism.” This current was, however, in the view of many (myself included), better understood as an effort to revise the revolutionary elements of Marxism. And it came to us complete with major academic influence along with a jargon that only the fully-initiated could understand. Today I write this essay to advocate a refounding of the Marxist movement. In contrast to the previous “rethinking” effort, I will suggest that we embrace the fundamentals of revolutionary Marxist ideology while remaining sufficiently self-critical to revise elements that have proven to be outmoded or mistaken. I address my appeal to the currents of activists who are still struggling for social change, rather than to an academic audience. And I insist that we must develop a process that helps demystify jargon, making our ideas accessible to the overwhelming majority of those who possess an average intelligence.

Why do I make this appeal? I do so because even though there are still clusters of activists and some prominent individual thinkers who identify their ideological approach as being part of the Marxist tradition, the individual thinkers are mostly content to remain that way while the clusters are fragmented into small collectives, most of them lacking any meaningful connection to genuine mass struggles. Marxist political life, to the degree such a concept can be discussed at all, has thus become largely ingrown, often focused narrowly and in a literally sectarian manner on a competition between each version of “Marxism” and all of the others. It’s hard for me to see how this condition will be overcome without a conscious effort to deconstruct what presently exists and reconstruct something new: a genuine, multi-tendency and non-sectarian Marxist collective attempting to apply an agreed set of political principles creatively to real political events, while simultaneously rejecting a process of splitting over tactical or strategic disagreements. We should even work harder to avoid splits that reflect differences of principle, dividing into separate organizations only when this is imposed on us by the conditions of the class struggle.

There remains, it is clear, a need to overthrow the global reality known as capitalism-imperialism-whitesupremacy-heteropatriarchy if our humanity is going to thrive, even if it is simply going to survive. Yet those who like to think of themselves as “revolutionaries” in today’s world, as being engaged in an effort to overthrow capitalism-imperialism-whitesupremacy-heteropatriarchy (including our Marxist collectives and individual thinkers just discussed), tend to be divided into two camps, neither of which is capable of achieving that goal. Some satisfy themselves with the struggle to tweak the present system in ways that may appear profound (“revolutionary”) in one respect or another, but still leave the system itself in place. Others genuinely seek to overthrow the current order of things but are insufficiently invested in the necessary scientific understanding of capitalism-imperialism-whitesupremacy-heteropatriarchy. Many in our second group pay some superficial attention to the scientific elements, repeating formulas they have learned by rote from a history in one “Marxist” political current or another that developed during the 20th century. But they show no real interest in a rigorous process of understanding or analyzing contemporary social realities and their relationship to Marxist theory.

I choose to offer this essay to the Cosmonaut website because I find that authors who are published in this space are capable of actively engaging in a theoretical exploration without lapsing into dogmatism, often working consciously (it seems clear) to apply a genuinely dialectical materialist methodology. I therefore hope that the germ of an idea that I am advocating in this essay might find fertile ground in which to sprout here.

You will see below that I call for our refounded Marxism to reject the viewpoint, common among 19th and 20th century Marxists, that Marxism is the only truly revolutionary ideology. I continue to believe, however, that it remains the most scientific. Whatever flaws we might be able to identify in past theories/practices of the Marxist movement, Marxism maintains an ability, characteristic of any scientific enterprise, to discover what’s wrong with its previous understanding and consider how to do better moving forward. This takes us logically to section II of this essay.

II. A critique of 19th and 20th century Marxism as our starting point

During their own lifetimes Marx and Engels were constantly honing and even revolutionizing their own ideology. The same is true of every Marxist—and even non-Marxist revolutionary—we can name from Rosa Luxemburg, Lenin, Trotsky, Alexandra Kollantai, Amilcar Cabral, Fidel Castro (to name some of the Marxists) to Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr., (to note two of the most prominent non-Marxists). Yet after their deaths the ideas of such individuals, Marxist or otherwise, tend to become codified, even enshrined, in a mode that worships the specific words they left behind—frozen in time and now immutable. This process inhibits, at the very least, and often actively precludes a further honing and even revolutionizing of our own ideology. Yet honing and revolutionizing our own ideology is the task imposed on us if we want to live up to the standards of historical revolutionaries whom we admire most.

In order to illustrate the importance of this insight I will offer two thoughts from Frederich Engels. In my 70s I have begun a study to ground myself more thoroughly in Marxist philosophy. It’s a subject that I paid some attention to, in a cursory way, over the years. But until now I had not invested sufficient time to acquire a reasonably thorough understanding. As I read I come across these two paragraphs in Anti-Duhring (Part II: “Political Economy” section I “Subject Matter and Method”):

This critique proves that the capitalist forms of production and exchange become more and more an intolerable fetter on production itself, that the mode of distribution necessarily determined by those forms has produced a situation among the classes which is daily becoming more intolerable—the antagonism, sharpening from day to day, between capitalists, constantly decreasing in number but constantly growing richer, and propertyless wage-workers, whose number is constantly increasing and whose conditions, taken as a whole, are steadily deteriorating; and finally, that the colossal productive forces created within the capitalist mode of production which the latter can no longer master, are only waiting to be taken possession of by a society organized for co-operative work on a planned basis to ensure to all members of society the means of existence and of the free development of their capacities, and indeed in constantly increasing measure.

In other words, the reason is that both the productive forces created by the modern capitalist mode of production and the system of distribution of goods established by it have come into crying contradiction with that mode of production itself, and in fact to such a degree that, if the whole of modern society is not to perish, a revolution in the mode of production and distribution must take place, a revolution which will put an end to all class distinctions. On this tangible, material fact, which is impressing itself in a more or less clear form, but with insuperable necessity, on the minds of the exploited proletarians—on this fact, and not on the conceptions of justice and injustice held by any armchair philosopher, is modern socialism’s confidence in victory founded.

There is much to embrace in Engels’s words, of course. But each paragraph contains a statement which we, today, need to think about critically (emphasis added in the partial quotes below):

1) “The colossal productive forces created within the capitalist mode of production which the latter can no longer master, are only waiting to be taken possession of by a society organized for co-operative work on a planned basis to ensure to all members of society the means of existence and of the free development of their capacities, and indeed in constantly increasing measure.”

It seems likely to me that Engels, had he lived long enough to see how the productive forces of capitalism developed during the 20th century to an extent that was quite unimaginable when he wrote these lines, would have been among the first to acknowledge the contradiction between a “constantly increasing measure” of production and the need to maintain an ecological balance with the rest of nature. Still, this idea that socialism will “free up the productive forces” and allow a “constantly increasing” production of material goods (an “abundance”) is a theme that runs through the writings of 20th century Marxists too, persisting among many even to the present day. In the year 2023, however, we have to reject this idea. The global ecological crisis demands that our socialism find a way to reduce the destructive consumerism of contemporary capitalism that does nothing to enhance life-satisfaction (quite the contrary) yet imposes an impossible burden on our planet. Non-material things like leisure time for sports, the arts, life-long education, the pursuit of human relationships, etc. need to replace the consumption of material goods as the way human beings pursue a satisfying existence.

2) “If the whole of modern society is not to perish, a revolution in the mode of production and distribution must take place, a revolution which will put an end to all class distinctions. On this tangible, material fact, which is impressing itself in a more or less clear form, but with insuperable necessity, on the minds of the exploited proletarians—on this fact, and not on the conceptions of justice and injustice held by any armchair philosopher, is modern socialism’s confidence in victory founded.”

This idea that the victory of socialism is the inevitable (or nearly so) outcome of the class struggle, because the very nature of working-class life impresses a consciousness on that class “with insuperable necessity,” represents another theme that runs through the writings of 19th and 20th century Marxists. Today, at a time when “this tangible material fact” is further from the conscious minds of most exploited proletarians than it has been for more than a century and a half, it seems clear that we must proceed with considerably less “confidence in victory.” The possibility that “the whole of modern society will perish” seems like an increasingly probable outcome. What we can say today is that the victory of ecosocialism remains the only alternative to the catastrophic collapse of modern society—a thought which makes it imperative for us to reject giving up in despair, redouble our efforts instead since we now realize that the subjective factor (what human beings like us choose to do) is almost certainly going to be decisive. It also makes the question of how we focus our subjective energy in ways that can be most strategic for toppling empire and replacing it with a global ecosocialist society even more important than it was in the past.

These are just two examples of old Marxist ideas that our refounded 21st century Marxism must reconsider. Let’s now proceed to a more comprehensive list, both of ideas we need to reconsider and those we need to affirm in my judgment.

III. Envisioning a 21st-century Marxism.

The two lists I present in this section have no status except as my personal examples—ideological points which a refounded Marxist movement must either revise or embrace. I start out with the optimistic assumption that a collective will develop at some point that wants to pursue the project of “refounding” I propose, and that as we work on this project the lists of things to reconsider and maintain compiled by others will differ, at least in part, from the ones I offer below. The process I envision requires each of us to consider our own ideas in the context of alternative suggestions, striving to develop a collective list that can be stronger than those any of us might be able to compile on our own.

A) Some additional ideas that we need to reconsider:

1) Marxism is not the only revolutionary ideology. Our refounded Marxist movement must see itself as part of a complex web of revolutionary ideologies which includes many in today’s anarchist movement, ecofeminism, liberation theology, indigenous and nationalist revolutionary currents among others. I do believe that Marxism has an essential role to play as part of this revolutionary web. But it can only do so if we start out with an attitude of respect for others who are also part of the same constellation of revolutionary forces that we are.

2) The successive stages of economic development that European cultures passed through, from slavery to capitalism, should not be thought of or presented as “progress.” More productive does not mean “higher” or even “more evolved.” Stephen Jay Gould debunked the idea that biological evolution proceeded steadily from “lower” (less organized) to “higher” (more organized) species. We have to engage in a similar demystification of “progress” in social evolution.

3) Related to #2: we need to reject any sense that the economic development of Europe is, somehow, a standard by which all other nations of the world can be measured. Marxism has been accused of Eurocentrism, and in this sense the critique has some validity. Marxism, from its founding, was rooted in a European/North-American experience of capitalist development. It has been weak in acknowledging other experiences, and a potential for those experiences (in particular indigenous experiences) to help us shape the future of the human race. A European/North American mindset that is blind to this weakness is something we need to consciously work on, especially because a European/North American mindset comes so naturally to Marxists who were born and raised in Europe or North America.

4) The role of the working class has to be reconsidered—not dismissed but re-imagined and nuanced considerably. The old Marxist idea of the working class as the natural repository of revolutionary instincts because of its relationship to capitalist production has not been validated by the experience of the 20th century. The development of a labor aristocracy, the grip of the labor bureaucracy, and the seduction of consumerism within more privileged layers of the working class—along with the aspirations created by consumerism among the less privileged layers—have proven to be effective countervailing forces which retard, even reverse, the development of a revolutionary consciousness. Other social layers—in particular oppressed nationalities—can be more advanced in their consciousness than the great mass of working people. At the same time the strategic importance of the working class as a social force that can actively cripple capitalist production through a general strike remains a key element, probably the key element, in most potential revolutionary processes. Thus while the working class remains one important revolutionary subject, it would be an error to conceive of it as the only revolutionary subject. Perhaps it is not even the most important—in specific moments or specific social contexts.

5) Related to point 4: There has been a tendency for at least some Marxist currents to treat the struggle against capitalism as somehow more central than other liberatory struggles in our contemporary world, even to theorize that if capitalism is overthrown the rest will take care of itself. There are alternative Marxist currents that have done better than this, of course, but a certain tendency to focus on anticapitalist struggle as the keystone in an arch of anti-oppression remains. Our refounded Marxism should, in my view, treat capitalism-imperialism-whitesupremacy-heteropatriarchy as a single integrated whole, which requires resolution as a package. The solution cannot be reduced to a series of individual solutions to the individual components of oppression that make up that package. There is also no “hierarchy” of oppression with one more fundamental than the others. The liberation of the working class cannot take place without the liberation of oppressed nationalities, the abolition of racism in all its forms, and the end of oppression based on sex or gender.

6) Too many Marxists have committed themselves to building vanguard formations (a commitment I believe must be retained, see point B5 below) in a way that leads to the construction of close-knit factions rather than political parties. A 21st-century Marxism must reject the idea of the faction-party, seek to build parties that represent a broader unity, embracing Marxists with a range of ideas and opinions on specific matters. If we look back at what I consider the most successful Marxist party in history, the Bolshevik Party that made the Russian revolution of October 1917, it was not a monolithic or even “homogeneous” formation. It was characterized by an openness to debate and to the conflict of ideas—without people becoming enemies of one another or being considered enemies of the party. I will argue that without this capacity the October revolution itself would have been impossible.

B) Some ideas that we should maintain:

1) The philosophy of dialectical materialism must be restored as the key foundation of our scientific method in relation to economic and political questions in particular, along with everything else. It is this which made the work of Marx and Engels scientific. It’s the only approach to the world that can make our current practice scientific too. Yet a study and, more importantly, a practice that reflects the dialectical side of this duality is difficult to find among most who have presented themselves as practitioners of Marxism—at least during the last half of the 20th century.

2) The basic laws that govern production-for-exchange that Marx discovered (or adopted from previous political economists), and which underlie all economic relations in class society—starting with the law of value—remain the foundation of our own economic understanding.

3) We maintain the theory of the state as a bulwark of ruling class interests, affirm the need for an insurgent revolutionary movement to overthrow the old state power and impose new state forms that will reflect the democratic aspirations of a popular mass movement.

4) Without revolutionary theory there can be no revolutionary action. Without revolutionary action there can be no revolutionary theory. These two elements co-exist, each one representing cause and each one representing effect in a chain that can never be stronger than its weakest link. This is what we mean by a “revolutionary praxis.”

5a) The task of developing that revolutionary praxis can only be undertaken by a cadre organization which understands it as a conscious task. When I joined the Socialist Workers Party in 1968 it was an axiom of the movement that a revolutionary organization could not exist without a theoretical journal. There are socialist theoretical journals (including Cosmonaut) that remain, but for the most part they are disconnected from organizations—and therefore not actively engaged with a collective political practice—while most self-proclaimed revolutionary organizations proceed today without paying serious attention to theoretical matters. Their “theory” is often limited to the occasional quotation that can be used to reinforce their own commitment to a pre-existing dogma.

5b) The cadre organization must attempt to become a two-way transmission belt between its own consciousness and a broader mass movement—thus enabling itself to learn from the experience of the mass movement, while also helping the mass movement to act in a revolutionary manner during historical moments when revolutionary action becomes possible. (This is Lenin’s theory of a vanguard party, properly understood.)

6) The key programmatic method by which a vanguard formation attempts to make connections with a mass audience is through the use of a “transitional program,” a concept first theorized by the Comintern in the 1920s, though it was previously implemented (without being consciously formulated as a strategy) by the Bolsheviks in 1917.

7) The right of nations to self-determination (once again developed in its clearest form by Lenin) remains a core principle of a refounded Marxist movement. At the same time, and for the same reason, we reject any action by newly-liberated nations to subjugate their own national minorities.

8a) There can be no theoretical separation into “stages” of democratic and socialist revolutionary tasks in the age of imperialism. A single revolutionary state, representing an insurgent mass movement, must be created that undertakes both kinds of tasks—those that remain unfulfilled from the bourgeois-democratic revolution and those that flow directly from the socialist revolution—either simultaneously or in sequence. (This is Trotsky’s theory of “permanent revolution,” properly understood.)

8b) There is, therefore, a class struggle within any national liberation movement between its bourgeois and proletarian elements, with the bourgeois forces attempting to restrict any victory to purely bourgeois-democratic tasks while the proletarian elements have an active interest in advancing the socialist tasks as well. The hegemony of bourgeois forces in this internal class struggle is as much a threat to the genuine completion of the democratic revolution as it is to the socialist revolution.

Conclusion:

There is no collective in the USA (or anywhere else) that I am aware of which meets all of the requirements suggested by what I have written above. There are groups that collectively embrace pieces of the necessary approach, and there are many scattered individuals—coming from a wide variety of historical traditions—who are capable of making meaningful contributions to the kind of refounding I have suggested here. There are also many young people drawing conclusions that can only be characterized as “revolutionary” in a subjective sense, but who tend to gravitate toward sectarian formations because they see no alternative, or else find their revolutionary spirit subordinated to the work of some NGO, or channeled into essentially reformist forms of electoral politics or single-issue organizing. The task is, therefore, a recomposition and refounding of a serious Marxist current in the USA that will attempt to implement the necessary praxis (that is, developing theory in relation to action and developing action in relation to theory) in a non-sectarian manner while appealing to the best of the younger generation.

A discussion stimulated by this article is, I am hoping, a place to start that process. It can be nothing more than a place to start, of course. But the process has to start somewhere.